November 12, 2021

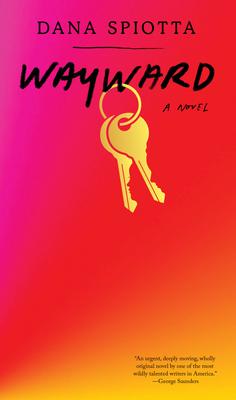

Wayward, by Dana Spiotta

I recently read Dana Spiotta’s novel Wayward in one sitting, not necessarily because it was it was unputdownable, but because I’d chosen it for the Turning the Page on Cancer Readathon a few weeks back. And it turned out to be a perfect selection for such a thing, the novel utterly absorbing, although I read it kind of deliriously, now that I think about it. It’s a pretty intense novel with a whole lot to unpack, and so the affect of reading it all in one burst was a bit like being smacked in the head with a baseball bat, but in the very best way possible.

It’s a highly specific novel about something so many of us tend to speak about in general terms, namely what happened when the world went off the deep end in 2016. For Samantha Raymond—whose mother is ailing, whose daughter is coming of age, who suddenly finds herself unable to sleep at night—this surreal moment in the universe sends her life into a tailspin when she decides to leave her comfortable suburban home, and her marriage, purchasing a ramshackle historic home in a dodgy neighbourhood in Syracuse.

The first line of the novel: “One way to understand what had happened to her (what she had made happen, what she had insisted upon): it began with the house.”

“It began with the house” could well be the opening line to most novels that I love.

Wayward is a twisty, tricky novel, that’s also about mid-life, aging, about feminism, about white feminism, about cities, neighbourhood, community, motherhood, daughterhood, about notions of justice and what it means to lead an authentic life. As can be expected from the title, Sam’s pursuit of such a thing is not straightforward, usually ill-advised, and hers is a story of mistakes and wrong-doing, the inevitability of these, the impossibility of purity, of the possibilities of redemption.

November 2, 2021

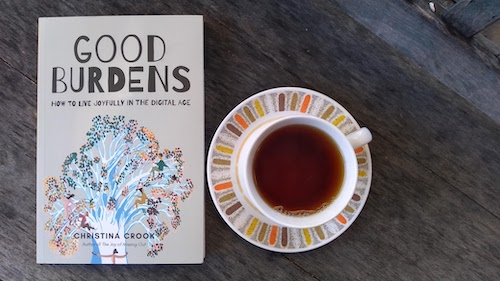

Good Burdens is here!

If my Blog School course had a textbook, Christina Crook’s Good Burdens would be it, a heartful and inspiring book about living a mindful and joyful digital life. After blogging for more than twenty years (and using my social media platforms as an extension of my blogging space), I know that the tools of the internet are capable of making our lives richer and deepening social connections, but that involves considered and deliberate practice, a willingness to go against the grain and serve ourselves (and each other) instead of an algorithm. And the payoff? A meaningful online life whose riches spill over into the real world in the form of friendships, inspiration, and creative work.

What is a Good Burden? Our good burdens are the work we do to that add meaning to our lives—partaking in a community project, putting dinner on the table where family will gather, sending a card or a letter to a friend. In a world where technology promises endless ease and convenience, it’s too simple to forget how much these kinds of gestures matter, both to our communities and to ourselves.

And in Good Burdens, Crook shows that the notion of good burdens can bring light and meaning to our digital experiences, and also to the rest of our lives. She urges her readers to pay attention to the world around them and to those things which deliver joy. What is joy and how do we find it? How do happy people use technology differently than other people? What makes a good life? How do you get there?

The book is a warm, inviting and engaging read, but also structured as a workbook with space for readers reflect and write down ideas, offering personalized approaches instead of one-sized-fits-all solutions, urging us to ask ourselves the right questions instead of promising answers. Good Burdens is about ideas that I think about a lot, but I still found it rich and inspiring—and really enjoyed the opportunity to talk with Crook on a recent episode of her JOMOcast all about the spaces where her ideas and my own blog thoughts overlap.

I first read this book as an advanced reader copy, and liked it so much I pre-ordered a finished copy, and then the publisher sent me a finished copy, so now I have two! If you would like the chance to win a copy of Good Burdens, make sure you’re signed up for one of my newsletters (sign up for the Pickle Me This Digest or the Blog School Newsletter) for a chance to win my spare copy. If you’re on my mailing list already, watch your inboxes—coming Friday!

And if you just can’t wait, you can go to your local bookstore and pick up Good Burdens today.

October 31, 2021

Hauntings: Books That Won’t Leave Me Alone

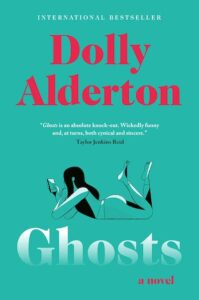

I loved this book, which I thought was going to be a smart and funny novel about modern dating and the phenomenon of “ghosting,” which it was, but it was also so much richer and more meaningful than that as Alderton’s protagonist comes to understand the different kinds of ghosts that are haunting her experience—ghosts of a past romance, of her childhood, and also of her relationship with her parents, which is changing and becoming more complicated as her father’s dementia progresses.

*

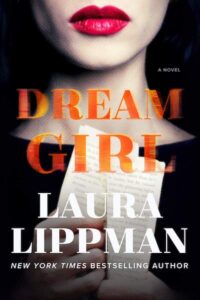

Reading the latest Laura Lippman is a summer holiday tradition for me and my husband. We love her, and her latest, a literary homage to Stephen King’s Misery, is a marvelous mindfuck. Lippman moves from crime fiction to psychogical thriller in this novel about an author who becomes confined to his bed and then proceeds to be haunted/hunted by a character from one of his novels. We loved it, and the meta elements of it all were delicious.

*

The Other Black Girl, by Zakiya Dalila Harris

This one checked a lot of boxes for me—set in the publishing industry, biting social commentary, and twisty and weirder than you’d think, billed as “Get Out meets The Stepford Wives.” Naturally, Nella is pleased when the new hire at her office means she’ll no longer be the only Black girl at her publishing company, but her comradeship with Hazel turns out to have an edge. The novel is a statement on racism and feminism, the notion of how much progress is enough, and a culture of scarcity that means supporting others could mean hindering one’s own chances of success. But it’s also more than that, totally bonkers, involving an underground movement, and a fight back after decades of oppression.

*

Malibu Rising, by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Everyone keeps telling met that the The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo is her best, but I haven’t read it yet. I did read Daisy Jones and the Six and liked it well enough, but I LOVED Malibu Rising, a holiday dream of a novel that I read in a single day and then forced until my husband who liked it as well as I did. Complicated family dynamics, Americana, California, and the sea. The novel had some furious momentum and I found it unputdownable. I can’t think of any literary ghosts in this one, but characters are indeed haunted—by lost loves, and the people they used to be.

*

A Thousand Ships, by Natalie Haynes

We read The Odyssey earlier this year, and I ordered this book afterwards, inspired by that book and also events in The Iliad, though I confess that I wasn’t chomping at the bit to read it, figuring it would be difficult. Those Greeks, you know? But I loved it. Read it right after Malibu Rising and just as quickly while we were on holiday this August, and then my husband read it, and then our daughter did, and it brought these characters to life in the most vivid, devastating way, because this is a novel about death and loss and destruction after all. There is nothing heroic in these wars, which tell the story of how their experienced by many different women. I can’t wait to read The Iliad now

October 20, 2021

The Most Precious Substance on Earth, by Shashi Bhat

In 2018, when I had the great honour (and pleasure!) of being one of three jurors for the Journey Prize, one of the standout parts of that experience was encountering Shashi Bhat’s writing for the very first time. Although I didn’t know the writing belonged to Bhat herself—the stories were submitted anonymously. All I knew was that “Mute,” which would go on to win the prize, was utterly distinct in terms of its narrative voice, and its clarity, and its point of view. So smart, and wise, and funny, and sad, and I don’t know that I’d ever read anything else quite like it.

And now with The Most Precious Substance on Earth, Bhat’s debut, there’s an entire book of this, and I just loved it, and was just as struck by Bhat’s storytelling as I was the first time I encountered it—her award-winning story “Mute” is actually included in the novel. Which indeed does function as a novel—just as it also stands up an impressive collection of short fiction, as Steven W. Beattie argues compellingly in a recent review—because the entire book is so satisfying and rewarding as a whole.

At first, the appeal was nostalgic, familiar, and I texted my best friends to instruct them to get their hands on this book immediately, because Bhat’s tales of late 1990s high school were just so absolutely transporting to this particular reader (me!) who spent Grades 9 and 10 eating lunch on the dusty wooden floors in the alcove outside the science office of a high school at no longer exists. But it wasn’t only the nostalgia—the stories were so evocative because of the specificity of Shashi Bhat’s eye, which is to the eye/I of her protagonist/narrator Nina, who must seem detached from the outside, and we can understand that she sees everything, even the details she’s still too young and naive to process, such as her inappropriate relationship with English teacher.

It’s all so funny, deadpan, tortured and awful, Nina’s best friend Amy, and her boyfriend, and the way she peels the floors. The absurdity of ordinary experience, which is especially the case in high school, and the novel takes us from Grade 9 to a fateful band trip, and Nina’s coming of age, and the way in which she seems to weigh everything evenly, no judgment. The weight of what her did to her, or what happened to Amy, or what it’s meant to to so often be the only person of colour in spaces that were overwhelmingly white—none of this becomes apparent until much later, and it might be easy for a reader to suppose these experiences don’t actually matter much at all.

But all this is also not to say that Nina is a nonentity, just a simple observer—it’s the specificity of these characters and their experiences that so exalts Bhat’s writing. The baked ziti, and the tomato plants, and that Nina joins Toastmasters, and her parents’ eccentricities—there is nothing general about it, and these are the details that bring these stories to life. They’re also often very funny, Bhat’s prose just as assured and confident. She’s an extraordinary writer, and this is an extraordinarily good book.

October 15, 2021

The Strangers, by Katherena Vermette

How does one follow a book like Katherena Vermette’sThe Break, a fast-paced novel with a thriller’s edge that managed to wed deft plotting to high literature, a book that was so rich and satisfying, and brutal and heartbreaking at once?

Five years on, Vermette answers the question with her second novel, The Strangers (though she’s been keeping busy in the meantime releasing poetry and a graphic novel series, among other creative projects), which is billed as a “companion novel” to The Break, and has already been longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and nominated for the 2021 Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize.

The Strangers is not The Break, and though it features some of the same characters, someone looking for a similar reading experience might end up disappointed. Rohan Maitzen’s excellent review notes that the novel lacks its predecessor’s urgency: “Even as time passes in it, The Strangers doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. It ends on a faintly hopeful note, but the conclusion doesn’t feel like a resolution: it’s just the next thing that happens.”

And yet I still found the novel compelling, in the stories of Phoenix, who gives birth in detention and has to give up her baby, and Elsie, her mother, stuggling to stay sober, both of them entrenched on a system that separates women from their children, exacerbating the estrangement and broken ties that created so many of these Indigenous characters’ struggles in the first place.

On a language level, I think the book is really interesting, Elsie and Phoenix’s sections written in the the way that these characters speak, not just in dialogue, the prose not adhering to the usual rules of grammar, though in a natural, easy way that doesn’t interrupt the reading. The sections in the voices of Elsie’s mother, Margaret, and Elsie’s other daughter, Cedar, are very different, reflective of these characters different levels of education, the different company they’ve kept, underlining one of the book’s most salient points: the two people can come from the very same place and each turn out so differently. That what’s easy for one person might prove impossible for someone else.

So no, the plot doesn’t zip, but perhaps the ploddingness is not an accident, especially when you consider time from the perspective of a character counting the days since the last time she got high, or from that of a woman who’s counting down the days until she gets out of jail, trying (and failing) to overcome her violent impulses. Life itself is hardly deftly plotted, which might be the point of the entire book. Instead, it can be random, often lonely, and tragically unjust, especially for those who are marginalized.

October 6, 2021

Apples Never Fall, by Liane Moriarty

Liane Moriarty is a master of fiction, her genius undermined by her popularity, which makes many readers suspicious. Because how good can a writer possibly be if her bestselling novel gets made into a series by Reese Witherspoon and Nicole Kidman? A question to which I reply: she is so good. Truly Madly Guilty and Big Little Lies are both fantastic novels weaving BIG PLOT with the most sophisticated characterization, her fictional people complex and multi-dimensional, revealing their secrets in rich and surprising fashion which means the plot twists generally deepen the story instead of undermine it. I LOVE HER. The plots themselves undeniably frothy and too much, but in the best way, anchored by the human people at the heart of them. And her latest, Apples Never Fall, does not disappoint.

Which is a relief, because her previous novel, Nine Perfect Strangers, arrived as a bit of a letdown, Moriarty having come up with a fantastic cast of characters, each with luscious backstories, but it all failed to coalesce with an over-the-top preposterous plot and would have made a better short story collection. Because the trouble with a novel about perfect strangers is their lack of connection to each other, which is the kind of spark that lights the fuse.

In Apples Never Fall, however, she’s made her characters a family, which means there are sparks aplenty, decades of grudges and misunderstanding. Joy and Stan Delaney are celebrated tennis coaches whose own children were raised in an ultra-competitive, high intensity atmosphere, each of whom knows they’ve proved disappointments in their own special way. And when Joy suddenly disappears and Stan appears to be the prime suspect, each is afraid to voice their suspicions for fear they might be true.

It gets worse—detectives find a t-shirt soaked with Joy’s blood. Stan is becoming more and more difficult. There there is the matter of the curious house guest, a wayward girl who’d stayed with Joy and Stan after fleeing an abusive relationship a few months before whose story is not quite what it seems. Each of the four Delaney children suspicious of their father, but also each other, and wondering what else they know about their family might turn out to be founded on a lie?

I liked this novel so much for the way it complicates all kinds of ideas about family, marriage, truth and lies, about domestic violence, and anger, and the ways in which we know and fail to know each other. I love how each twist had us understanding these characters on an even deeper level, and how these twists also demonstrate what these characters don’t even know about themselves. And I love how all the threads come together at the end of the book in a way that was surprising, and even refreshing, such a perfect culmination of a most enjoyable read.

September 30, 2021

Fight Night, by Miriam Toews

Nobody in any of Miriam Toews’ novels is ever any good at being anybody but the people who they are, which are people who are so achingly real, human, complicated, messy, furious, alive. It’s also impressive that while Toews returns to the same themes over and over in her work, in particular the experiences of contemporary secular Mennonites, she never writes the same book twice, pushing the limits of point of view and just what a novel can possibly contain, and her reader gets the sense that she’s actively resisting anything close to boredom. Which means her books are never boring, even if—as is the case in her latest, Fight Night—not much actively happens in the way of plot at all.

But no matter. Who needs plot when you’ve got voice? And to that end: meet Swiv, whose point of view propels Fight Night from start to finish, a Toewsian voice if there is such a thing. A young, precocious misfit who is wise beyond her years, Swiv had been kicked out of school for fighting and spends her days with her eccentric grandmother watching Call the Midwife while her very pregnant mother, an actress, rehearses for a play. Swiv’s aunt and grandfather have both died by suicide, and she’s concerned her mother is headed for a similar fate, all the while she’s terrified her grandmother might pass away at any being, kept alive as she is on a cocktail of various medications.

The novel’s structure is a letter Swiv is writing to her father as she anticipates the birth of her new sibling and also her imminent abandonment by everyone she loves. She doesn’t actually know where her father lives. Swiv is terrified, and taking responsbility for all the adults in her life who are being overwhelmed by their own burdens.

And have I mentioned that the novel is terrifically funny? If you’re familiar with Toews, you’ll already know that. The gap between the world as it is and how Swiv’s sees it is very funny, as is her fierce dignity, and her prudishness in contrast to her ribald grandmother who gets quite a kick of mortifying her. But of course, (and if you’ve read Toews, you’ll know this too) it’s also heartbreaking, especially that this young person is carrying the entire world on her shoulders.

So there is laughter, yes, and there is crying. There is life, and there is death. There’s also a trip to California, a perilous plane journey home, Jay Gatbsy perpetually knocking at the door, busses and boats, and books sawed in half so they’re easier to hold. There is love and there is rage and there is ferocity and gentleness, and so many ways to keep fighting, so many reasons to fight.

September 15, 2021

Beautiful World, Where Are You

It’s been more than two years since I read Normal People, and even more since Conversations With Friends (which I wasn’t crazy about, didn’t live up to the hype for me) so I can’t remember if all Sally Rooney’s novels have reminded me of Virginia Woolf, but Beautiful World, Where Are You, her latest, sure did. The curious omniscience, the sea, the tide, the house, echoes of Chloe and Olivia… It’s a strange and demanding novel, really, and so intense. I wasn’t really reading it at first with the appropriate amount of focus, and it was hard to get into. There’s nothing light and breezy about it with its lack of breaks for dialogue and paragraphs, and the density of the narrative as well, capturing every little detail of modern life for these twenty-somethings in contemporary Ireland.

Alice and Eileen are friends, and Alice, who has just published two successful novels and become a publishing sensation, is living alone in the countryside, she and Eileen writing each other long and involved emails about their daily lives, about the men who are their preoccupations—Alice has a strange connection to Felix, a working class local she met on Tinder, and Eileen is infatuated with Simon, an older family friend who she’s known her entire life who sometimes she sleeps with, sometimes even when he has a girlfriend. There’s also a whole lot that goes unsaid between the friends, or unconsidered (the email chapters are broken by chapters with the four characters going about their daily lives) which is a strange thing considering how no one ever shuts up.

The exchanges between Eileen and Alice are heavy, as their consider the prospect of societal collapse, and the meaning of life, or if there’s even such a thing, and I honestly found it all very stressful at first, just because I worry about this stuff all the time and I don’t really need literature that leads me deeper into my worst anxieties. But also the narrative is wholly engaging—as I’ve written in other posts, I’m so profoundly not interested in many contemporary novels featuring bored and detached protagonists where there really isn’t any meaning at all. There is a heart and soul to this book, even with its navel gazing consideration and preoccupation with minutiae. Things matter. Life matters. Friendship matters, and in fact it may be that the connections between us are all that matters—and I loved this as a revelation. How subversive in our age of cool detachment to even venture such a thing, but Sally Rooney’s already mindblowingly popular so the haters are going to hate, so why not just go all in on the feeling. Which is not sentimental, I mean, if sentimental is a bad thing. If sentimental means slight or shallow, because there is substance here, truth and beauty.

Turns out I loved this book a lot.

September 3, 2021

Householders, by Kate Cayley

I was a big fan of Kate Cayley’s How You Were Born in 2015, and have been looking forward to her latest release, the short fiction collection Householders, which is out this month from Biblioasis, and it didn’t disappoint in the slightest. The first story, “The Crooked Man,” literally took my breath away, a story of overwhelming motherhood, family life in the city, and violence on the margins of everyday experience, and a similar ominousness infuses all the stories throughout the the rest of the collection. That no matter how much we try to hunker down in our houses (whether they be a Toronto semi, a bunker during the zombie apocalypse, or a commune in rural Maine), the world creeps in, and we can’t stop it.

The stories are loosely connected, the narrative about the commune in Maine serving as an anchor. Carol and Nancy arrive there in the late 1960s, and Nancy stays, becomes Naomi, falls under the spell. Naomi’s story and that of her daughter are woven throughout the rest of the book, right up to the present day, amidst stories of a man who offers mercy (or is it?) to a legendary musician past his prime; a woman who pretends to be an nun online; a woman reflecting on a strange and complicated relationship with a troubled woman she’d known during her university years.

Kate Cayley is splendid in her deft arrangement of the sentence, and in her depiction of the quotidian but just askew enough to be new and surprising. These stories are rich, absorbing, and oh so satisfying, and I predict this as one of the big books of the fall literary season.

August 23, 2021

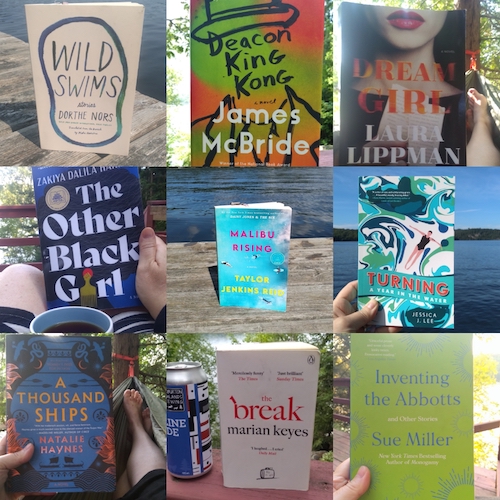

Holiday Reading Part 2

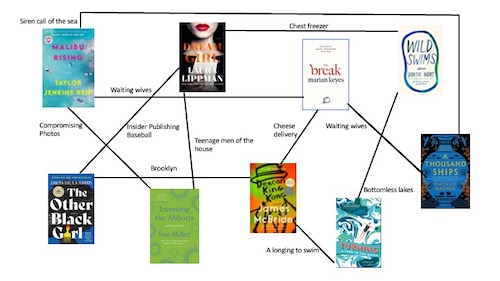

There were no duds in this stack, and even the title I was most intimidated by (hello, novel about the Trojan War!) blew me away. Every single one of these very different books was an absolute stunner, and the connections between them (as always!) were fascinating—see chart below. I was also so happy to reread Turning, which I’d read on vacation three or so years ago, and which I enjoyed but found so SPECIFIC that I wasn’t quite sure it would resonate again, so I gave it away, which I regretted for years. A new copy found its way back into my life this year, however, so I was happy to read it again. By a lake, of course.

I LOVED Malibu Rising—while I liked her previous novel, it didn’t quite live up to the hype for me. This one, however, was amazing. Every Sue Miller book I read is a pleasure. The Laura Lippman book was the most wonderful mindfuck, as was The Other Black Girl, both of which take on writing and publishing. Happy to read my second Marian Keyes—she’s really so good. A Thousand Ships was incredible, and Stuart and Harriet both devoured it after I did. Wild Swims was weird, but neat, and short, which is just the kind of portion I can take my weird in.

And finally Deacon King Kong, which I heard of somewhere, and then found in a Little Free Library shortly thereafter. It was rollicking, kaleidoscopic, huge in its scope, and tragicomic brilliance. Absolutely amazing.