January 16, 2023

Modern Fables, by Mikka Jacobsen

Modern Fables started out strong and never quit, a collection of personal essays that begin with a wake (with whisky, which leads to a brawl) and concludes with a wedding (with watermelon vodka-cocktails, which leads to Jacobsen fucking the best man, and the dissolution of her friendship with the bride). And in between, a wide of stories that take no sides, but instead examine every side—on sports and mascots (you can read an excerpt at 49thShelf); about a white Albertan’s relationship to the Indigenous peoples upon whose land she lives (complicated by her psychologist mother’s shamanism); such an artful revenge essay on a shitty ex-lover who turns out to be a plagiarist but which is also a treatise on women’s work and textile arts, and Mrs. Ramsay’s brown stocking.

In “Kurt Vonnegut Lives on Tinder,” Jacobsen notes how an affinity for the Slaughterhouse Five author is shorthand for something on the popular hook-up app, and resolves to figure out just what that means. “Modern Fables” tells the story of a relationship with a seeming pathological liar, and also catfishing, and cats, and rabbits, and other dead household pets. “Me vs. Brene Brown” is another story of a love story gone sour, in this case between Jacobsen and Brown’s ideas about been empathy and shame, which seem revolutionary at first, but Jacobsen soon realizes she’s read something like them else before (oh, yeah, right, in almost every work of literature ever, not least of all The Scarlet Letter), not to mention how Brown’s work seems to preclude the possibility of a fulfilling life outside of a nuclear family, and what Brown’s folksiness might suggest about what she thinks of the intelligence of her readership. And finally, “David Silver,” taking on the 90210 actor and other notable Davids (including he who battled Goliath) in a rich and provocative piece on mental illness, convening with the spirit world, and the possibility of cosmic order.

I loved this book, a collection that relit my flame of passion for the personal essay, a collection up there with Susan Olding’s two, which are some of the finest in CanLit—in Freehand Books, Jacobsen and Olding share a publisher. These essays are gorgeous, brutal, stunningly crafted, and pack a punch, like a one-two, WHAM, and then another, and then another, you’re sad when it’s all done.

January 10, 2023

The Radiant Way, Again.

The case against rereading The Radiant Way, by Margaret Drabble, was that my copy was a battered paperback with a tiny faded font, the cover stuck on with Scotch tape, that the novel was nearly 400 pages long, and that my ambition to reread Drabble’s entire ouvre in order a few years back had fizzled into nothing. That I’d just spent an entire fortnight on holiday reading one splendid back list book after another, and perhaps this one wouldn’t measure up. That I have a small mountain of brand new books to be read and if I fail to tackle it, the pile could possibly overwhelm me.

The case for it, however: that this was, perhaps, one of the most pivotal novels of my life. A novel that helped me come into my own as a reader and to begin to come into my own as a writer, after years of having my reading selections determined by course lists and ideas about what the classics were. In 2004, I picked up The Radiant Way in a Japanese bookshop (Wantage Books in Kobe, though there is a stamp for something called Juso Academy Used English Bookstore on the inside cover), the first Margaret Drabble novel I’d ever read, and I fell in love with this work, and decided that this was kind of book I’d like to read and write forever. And yes, in 2020, I’d decided to read through all her novels again (I have them all—secondhand copies until The Red Queen, at which point I began to read her as new hardbacks instead of battered old Penguins) but it never worked out. The early Margaret Drabbles were never so resonant for me anyway, too dated by the time I read them, preoccupied by once-provocative ideas that had ceased to be so. Too fixed in the first person, shallow in their grasp—but then perhaps I was expecting too much from novels written by someone in their early 20s more than 60 years ago.

I preferred Drabble’s novels published in the 1970s to the early ones anyway, but 1987’s The Radiant Way was where it really starts for me, possibly because it’s where it DID start for me. And I wanted to read it again, to see if it would measure up to my first experience of it almost twenty years ago when I was twenty-five and on the cusp of so many things, idealistic and yet disbelieving that real life could ever happen. When I didn’t know the stakes of things.

So I picked it up. And then closed it—the tape! That font! And then I opened it again, and started reading: “New Year’s Eve, and the end of a decade. A portentous moment, for those who pay attention to portents.” And I do pay attention to portents, so kept reading, supposing this a most fitting book for early January, and immediately captured by the incredible omniscience of this story, and the Dalloway-esque preparations for the Headleand’s New Year’s Party, except that Liz is hardly going to buy the flowers herself. Wife, mother of five, prominent psychiatrist to the upper classes—she is far too busy for that.

And that was it, I was hooked, and I read this book with butterflies in my stomach, as giddy as the first time I’d ever picked it up, moved because everything I’d loved so much about it twenty years ago was still remarkable—that omniscience, the novel’s consciousness of its form, the playfulness, postmodernism, the blurry line between fact and fiction (there is a part about the advent of a new political party which “also attracted the support of a good many of the characters in, and potential readers of, this novel…”), how Drabble is attempting to use the novel as a container for society, for the universe:

“Liz, Esther, and Alix were talking, with much animation and many an apparent non sequitur, about London districts, property prices, houses, the police, no-go areas, rape, violence, murder, robbery, Tennyson and Arthur Hallam, Leslie Stephen and Virginia Woolf… There was, perhaps, a thread linking this rambling, discursive, allusive, exclusive, jumbled topographical discourse…”

But even more remarkable was what I hadn’t noticed the first time—the attendance of characters at the Headleand’s party, for instance, who appear in previous Drabble novels, which I hadn’t yet read in 2004. I was reading this time too as a contemporary of the three protagonists, Liz, Alix and Esther, friends from Cambridge who’d found themselves in very different milieus by middle age, whereas before I’d been twenty years younger—and this is very much a novel about middle age, about middle grounds (Alix, a longtime socialist who’s now disillusioned, wonders if “making up one’s mind involves internalizing lies.)

Mostly, what blew my mind about rereading The Radiant Way was how familiar it all was, and not just because I’ve finally become the age its characters are. But instead how much England in 1980 feels like here and now, the same preoccupations, fears and instability. Rising inflation, right-wing governments, people losing their faith in any wing governments, labour unrest, budget cuts, a sense that the old ways and allegiances don’t apply anymore, disruptive technologies, how the working people pay for this change while the wealthy profit. Crime rates, an obsession with crime rates, and grisly murders, and an unwillingness to address the causes of such crime, and (for the labour types) to address just how difficult people can be—Tories are bad, but also (“wanted, idle, pointless, awful”) people wreck stuff just because they can. The tension between notions of the individual and society, which becomes especially fraught in the Thatcher years and and is so again in our current age of a new-new-Right (“What I can’t see, said Esther to Alix, is what any of this has got to do with you. Or with me. It’s simply not our problem. We didn’t make it, and that’s that. I’ve never met a miner, and I’m sure a miner wouldn’t want to meet me./ It’s not as simple as that, said Alix.)

A book full of questions that we’ve still not yet begun to answer…and yet it gives me some comfort to know that it was ever thus?

Anyway, I absolutely couldn’t get enough of this timely, artful, remarkable novel…but thankfully Drabble followed it up with two more books to make a trilogy, and I’ll be rereading both of these soon.

January 9, 2023

Holiday Reads

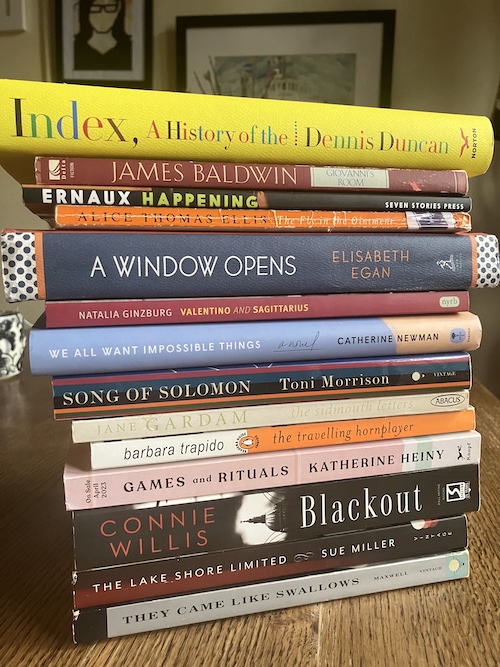

Our holiday break started a day before it was supposed to, as a blizzard raged outside and cancelled school and I curled up with THEY CAME LIKE SWALLOWS, by William Maxwell, a novel set against the Spanish Flu Pandemic and made me wonder why the word “unprecedented” was used at all in March 2020, because it really wasn’t.

And I read and I read, books I’ve been picking up here and there over the last year and finally time away from work (and social media) gave me time to delve into them. Some new books, others authors I love whose backlists I still get to delight my way through (Sue Miller! Toni Morrison! Natalia Ginzburg!). Barbara Trapido, whose work I’m falling in love with. I read HAPPENING, by Annie Ernaux, 2022 Nobel Prize Winner. OMG, SONG OF SOLOMON! GIOVANNI’S ROOM! Connie Willis’s time travel epic (and I have its conclusion still before me).

What a satisfying stack this is, a stack that’s inspired me to read (even) more off the beaten track in 2023, to pursue my own curious avenues.

Also now my “to be read” shelf is as spare and orderly as it will be for at least another year, and so before the deluge of new releases begins, I want to take a moment and appreciate that.

December 19, 2022

Awesome

Once they started coming for positivity, I got defensive. *Who are you calling “toxic”?* I thought. Looking on the bright side, for me, is like a reflex. It’s how I make it through, and while I think all of us learned something from conversations around positive thinking (guys, don’t tell a person with terminal cancer, “You got this”) “toxic positivity” became one of those internet ideas thoroughly drained of its meaning, lugubrious people using it justify their worst impulses in a world that seemed more doom-laden than ever, and I was having none of it. That light at the end of the tunnel was my lodestar and, without it, I’d be a heap on the floor.

And then the light went out, and I lost my way, robbed of tool that had always served me to keep going, one day at a time, and it was at this point that I learned two things about my relationship to positivity. One, that I suffer from anxiety, and so what might look like toxic positivity from the outside is actually me recalibrating from the fact that I was convinced we were all going to die and then we didn’t and oh my god how amazing is that. And two, that while finally learning to feel sad hard and difficult feelings is my path away from anxiety, positivity has a role to play too on this awfully bumpy journey. In March I was really struggling, and actually started a gratitude journal, walking cliche that I’m becoming, and oh my gosh, it’s been a wonderful tool. Along with therapy, and reading, and learning how to dig down deep into painful emotions I’d been avoiding my whole life, and learn how to really feel them. As with all things, it’s not one or the other, but both. The pleasure and the pain, the darkness and the light.

And to that end, Our Book of Awesome, Neil Pasricha’s first “Awesome” book in a decade, has made for a most enjoyable year-end read. Pasricha’s career as a bestselling author began years ago at a remarkably low point from which he started climbing out of the darkness one awesome idea at a time, illuminating miraculous aspects of ordinary life (warm clothes out of the dryer!), which he’d post on a blog that became a book…and here we are. This latest collection includes Pasricha’s own mini-essays, as well as contributions from members of his online community, teachers who’d used the book in their classrooms, and more.

Seeing someone in an online meeting smile as they read the direct message you’ve just sent them in the chat. When a human answers the phone. Actual newspapers. Good hand sanitizer. Library holds. “When the cake pops flawlessly out of the pan.”

Yup. It’s awesome.

December 8, 2022

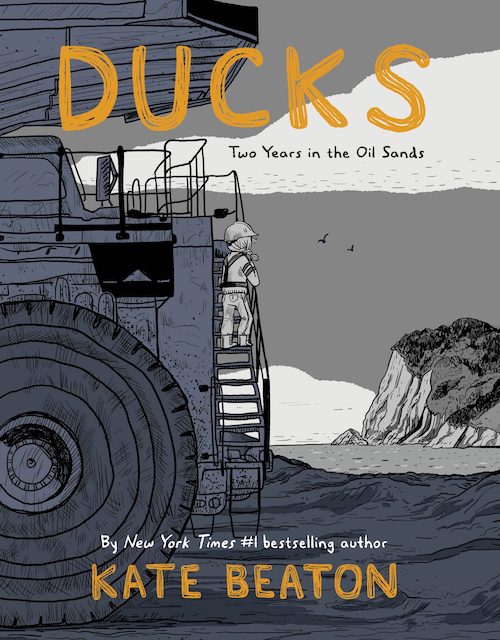

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, by Kate Beaton

In October I went to see Kate Beaton present her graphic memoir Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the force of that presentation kind of made the book itself beside the point, hence the reason I’m posting about it two months later, but it’s still on my mind.

Before Kate Beaton made a name for herself drawing ridiculously clever comics inspired by classic literature and history, she was an arts grad from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, with student loans to pay off and little opportunity for lucrative employment, and certainly not anywhere near her home, from which people have been leaving to find work since even before the coal mining industry went bust. In her AGO presentation (the most riveting, hilarious, generous, and vulnerable author talk I’ve ever been to, complete with music and singing), Beaton talked about her grandfather travelling to the prairies to find work as a farmhand, decades before her own journey west. She talked about what it does to a place to be robbed of its people and connections, and what it does to a self to belong to a place where you’re taught that a future isn’t possible.

In the early 2000s, Beaton moved to Alberta for well-paid work in the oil sands, and it was a strange and lonely existence rife with contradictions, which she captures beautifully in Ducks. Lonely and never alone, out of place but surrounded by people she recognizes as like those from home, earning money but nothing to spend it on, small in an immense awe-inspiring landscape being desecrated by industry.

Beaton’s drawings are composed in shades of grey, which is fitting for a story with such nuance. While Beaton doesn’t shy away from showing the reality of such a peculiar social environment, that women suffer in places like this, she also shows that the suffering isn’t limited, and that people being forced to travel far from home for work that is soul-destroying, not to mention ecologically devastating, are suffering too, and the real culprit is capitalism, a system that devalues people and communities, a system that pushes people to the point of breaking.

Beaton’s dream is to work in museums, putting her degree to good use, and she gets her break after a year in the oil sands, which she leaves for a part time position at a marine museum in Victoria…which turns out to barely be enough to live on, let alone pay off her loans, and so Beaton returns for another year in the Oil Sands, but here she begins publishing her comics on her Livejournal, pieces that would become Hark A Vagrant, from which Beaton would make her name, become a bestselling author, and (that rarest of things) an artist able to earn a living from her work. After a stint as a New York art sensation, Beaton once again lives in Cape Breton.

A happy ending then, but Kate Beaton is truly one in a million, and in the years since her time in the oil sands, she hasn’t forgotten what she saw, and what she learned. About humanity in the midst of inhumanity, and the worthiness of ordinary people to live good lives in the places where they come from. It’s not black and white, and that’s why Ducks is worth reading.

December 7, 2022

Gleanings

- As far as traditions go, chopping down a tree and planting it between the chesterfield and the tele for a month is pretty bizarre. But no one can dispute the delight a tree festooned with lights brings to a home and those who live in it

- I think it’s wise to check in from time to time with those stories we’re telling ourselves, about who we are.

- Considering myself one who’s typically up for an adventure, I’m always surprised how I long for familiarity. I’m still opening 3 drawers to find my hairbrush. I’m aware of the living room clock ticking and the buzz of the lights. I was cautious about setting off for a walk alone this morning for fear I might never find my way back.

- I was, and remain, furious at the caprice of memory. Someone mentioned to me recently being sorry they didn’t ask their parents more questions before they died and that’s the thing: I DID ask my dad all the questions I could think of. But you just can’t elicit interesting stories by demanding them–you have to know specifically that there was a ragman to ask if he had a horse, and to know that there was a horse to ask if anyone ever got to ride it.

- She says that if you think “I get you” often enough, you will feel the vulnerability of the other person and your judgement will shift to compassion.

- And so, to live a month in utter happiness, contentedness, joy: I can tell you that it rewired my brain, reset my soul. Obviously, I want to keep those good vibes going. How? So that will be my ongoing quest.

- Alissa achieves greatness (and very nearly the Nobel Prize). What does Roland have to show for his life, in his old age? A small hand in his, to lead him across the room. It’s an unexpectedly sentimental ending, from McEwan, another way in which this novel surprised me, but also pleased me. Maybe in his old age, he has tired of acerbity and cynicism, of twists that make us cringe or that shake our faith in each other and in the stories we tell.

- No heroism, no dramatic sopranos, no red capes. Just people being nice.

- There is a link here – but I’m aware I’m asking you, dear reader, to fill in some blanks*. Memories. Witnessing. Loss.

- I hope my work shines a bit of light in dark places and I hope it offers some inspiration and some joy, and I hope it’s always grounded in a bit of reality. Here’s to making a bit of magic where and when we’re able. Here’s to opting out of the traditions that don’t suit us. There are no supermoms here (or anywhere).

December 5, 2022

The Elephant on Karluv Bridge, by Thomas Trofimuk

“The elephant came, as I predicted, Really, in the span of more than six hundred years, an elephant was inevitable.”

A novel about an elephant escaped from the Prague Zoo, narrated by centuries-old bridge?

I wanted to read it, and purchased a copy in the summer that I’ve now scrambled to fit into my 2022 reads, and I’m so glad I did, because I loved it. Thoughtful, artful, playful (a note on an opening page reads, “Any resemblance to actual elephants, living or dead, is entirely deliberate), Thomas Trofimuk’s latest novel, The Elephant on Karluv Bridge, is an absorbing literary puzzle and truly a delight to encounter.

Sál, the elephant, escapes from the zoo, and The Bridge saw it coming, but of course, The Bridge has seen a lot already in six centuries. Everyone else on the streets of Prague, however, is caught unaware, including the zoo’s night watchman whose psychologist wife has decided she wants to have a baby, and an American recovering-alcoholic whose isolated life attending a lighthouse on a Scottish island is interrupted by her father taking ill in Prague and necessity that she rush to his bedside, her taxi colliding with a street performer with whom she finds immediate connection; an aging ballerina haunted by the ghostly presence of Anna Pavlova; the conductor whose choir is due to perform early morning on the bridge from which Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart peed into the river in April 1792, and whose lead soprano is keeping a secret; and a bodyguard with PTSD. All of these lives intersecting in ways that are both remarkable and otherwise, these intersections woven with the story of the elephant herself who carries memories of her early life in Zambia and the moments that brought her across continents and into captivity.

November 30, 2022

Flight, by Lynn Steger Strong

“What were the rules for loving people who were not obliged to love you? How did you know when and how to trust they wouldn’t destroy you too?”

Readers who were drawn to Lynn Steger Strong’s articulation of parenting and family life amidst an age of anxiety in her previous novel Want will find the same frantic tension in her follow-up Flight, but with an expanded canvas exploring the psyches of eight different people, including three siblings celebrating their first Christmas since their mother’s death, their respective spouses, and a local woman and her daughter in the rural town where they’re all spending the holiday with the looming question of what to do with their mother’s house hanging over their heads.

And oh yes, anxiety abounds, including financial anxiety, and parenting anxiety, and climate anxiety, and the existential drama of trying to be in the world when the one person who’d held that world and all its meaning together…is gone.

The book resonated, and I devoured it, the plot taut and so compelling as the siblings come together in a moment of extra-family crisis, but I also read it with great interst in and respect for its crafting, for the cumulative depths of so many different points of view, for how so many parts culminate in such a rich and satisfying whole.

Of course, there’s obligatory bitchiness and bad behaviour, all delicious and readable, inevitable when any family dynamic gets put under the microscope, but where Steger Strong really succeeds is in making her story more than that. Imagining something better, the possibility of warmth and connection persisting, of mutual understanding.

November 21, 2022

Ordinary Wonder Tales, by Emily Urquhart

‘I don’t think I just imagined her, the woman I was left alone with in the last few minutes before I was taken into surgery. I don’t know if she was a nurse, or some kind of technician, but she seemed terribly official, sitting at a table with paperwork while I contemplated the IV needle stuck in my hand. “Section?” she asked me, and I told her yes. “What for?” I said, “The baby’s transverse.” Lying across my womb, its little bum wedged in at the top and refusing to budge no matter how much I stood on my head, played soothing music into my pelvis, or shone a flashlight into my vagina. “Well,” said the woman at the table, sorting through her papers. “Kids will screw you somehow. If it wasn’t that, it would be labour, then they’d grow up to be teenagers. They always find a way.” “But it’s all worth it, right?” I asked her. “No.” She put down her papers. “I don‘t think it is.” Then she got up, left through a different door, and I never saw her again.’ —from my 2010 essay LOVE IS A LET-DOWN, first published in The New Quarterly

“She was a witch,” I said to my husband on Friday night as I was reading Emily Urquhart’s essay collection Ordinary Wonder Tales. (Our baby from the essay is now actually a teenager and was out babysitting somebody else’s children down the street.) “The woman from the hospital who told me that kids always screw you. You remember.”

And he did. Even though he hadn’t been there when it happened, had already been whisked away to get read for the surgery that would deliver our first child into the world, even though these were throwaway comments that someone had made almost fourteen years ago now, but those commets had haunted us, especially in those difficult months after her birth when I was afflicted with what I now know was postpartum depression, and they’d felt like a curse.

“If that was a story, she would have been a witch,” I said, Urquhart’s stories blowing my mind with their illumination of the links between ordinary and extraordinary, how the otherworldly lessons of fairy tales (or “wonder tales”) have much to teach us about our own experiences. Experiences including pregnancy, parenthood and living through a pandemic underlining that we’re all more connected to these stories than we might have imagined, to all that came before us, to superstition, signs and omens, and folklore. We’re all old wives, at heart, is what Urquhart is saying.

Urquhart, whose academic background in folklore informed her first book Beyond the Pale (she is also author of a celebrated book inspired by her artist-father), brings that same approach to these beautiful essays exploring the sublime edge of ordinary experiences including an ectopic pregnancy, childhood memories of a ghostly presence, sightings of her elder half-brother after his death in his 30s, a violent assault delineating the dynamic of woman as prey, an amniocentesis in an essay called “Child Unwittingly Promised,” a radioactive house in Port Hope, Ontario, and her father’s dementia against the backdrop of the Covid-19 Pandemic.

These essays—beautiful, rich and absorbing-will change the way you see your place in the world, and they’ll leave you noticing all the magic at its fringes.