October 20, 2021

The Most Precious Substance on Earth, by Shashi Bhat

In 2018, when I had the great honour (and pleasure!) of being one of three jurors for the Journey Prize, one of the standout parts of that experience was encountering Shashi Bhat’s writing for the very first time. Although I didn’t know the writing belonged to Bhat herself—the stories were submitted anonymously. All I knew was that “Mute,” which would go on to win the prize, was utterly distinct in terms of its narrative voice, and its clarity, and its point of view. So smart, and wise, and funny, and sad, and I don’t know that I’d ever read anything else quite like it.

And now with The Most Precious Substance on Earth, Bhat’s debut, there’s an entire book of this, and I just loved it, and was just as struck by Bhat’s storytelling as I was the first time I encountered it—her award-winning story “Mute” is actually included in the novel. Which indeed does function as a novel—just as it also stands up an impressive collection of short fiction, as Steven W. Beattie argues compellingly in a recent review—because the entire book is so satisfying and rewarding as a whole.

At first, the appeal was nostalgic, familiar, and I texted my best friends to instruct them to get their hands on this book immediately, because Bhat’s tales of late 1990s high school were just so absolutely transporting to this particular reader (me!) who spent Grades 9 and 10 eating lunch on the dusty wooden floors in the alcove outside the science office of a high school at no longer exists. But it wasn’t only the nostalgia—the stories were so evocative because of the specificity of Shashi Bhat’s eye, which is to the eye/I of her protagonist/narrator Nina, who must seem detached from the outside, and we can understand that she sees everything, even the details she’s still too young and naive to process, such as her inappropriate relationship with English teacher.

It’s all so funny, deadpan, tortured and awful, Nina’s best friend Amy, and her boyfriend, and the way she peels the floors. The absurdity of ordinary experience, which is especially the case in high school, and the novel takes us from Grade 9 to a fateful band trip, and Nina’s coming of age, and the way in which she seems to weigh everything evenly, no judgment. The weight of what her did to her, or what happened to Amy, or what it’s meant to to so often be the only person of colour in spaces that were overwhelmingly white—none of this becomes apparent until much later, and it might be easy for a reader to suppose these experiences don’t actually matter much at all.

But all this is also not to say that Nina is a nonentity, just a simple observer—it’s the specificity of these characters and their experiences that so exalts Bhat’s writing. The baked ziti, and the tomato plants, and that Nina joins Toastmasters, and her parents’ eccentricities—there is nothing general about it, and these are the details that bring these stories to life. They’re also often very funny, Bhat’s prose just as assured and confident. She’s an extraordinary writer, and this is an extraordinarily good book.

October 15, 2021

The Strangers, by Katherena Vermette

How does one follow a book like Katherena Vermette’sThe Break, a fast-paced novel with a thriller’s edge that managed to wed deft plotting to high literature, a book that was so rich and satisfying, and brutal and heartbreaking at once?

Five years on, Vermette answers the question with her second novel, The Strangers (though she’s been keeping busy in the meantime releasing poetry and a graphic novel series, among other creative projects), which is billed as a “companion novel” to The Break, and has already been longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and nominated for the 2021 Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize.

The Strangers is not The Break, and though it features some of the same characters, someone looking for a similar reading experience might end up disappointed. Rohan Maitzen’s excellent review notes that the novel lacks its predecessor’s urgency: “Even as time passes in it, The Strangers doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. It ends on a faintly hopeful note, but the conclusion doesn’t feel like a resolution: it’s just the next thing that happens.”

And yet I still found the novel compelling, in the stories of Phoenix, who gives birth in detention and has to give up her baby, and Elsie, her mother, stuggling to stay sober, both of them entrenched on a system that separates women from their children, exacerbating the estrangement and broken ties that created so many of these Indigenous characters’ struggles in the first place.

On a language level, I think the book is really interesting, Elsie and Phoenix’s sections written in the the way that these characters speak, not just in dialogue, the prose not adhering to the usual rules of grammar, though in a natural, easy way that doesn’t interrupt the reading. The sections in the voices of Elsie’s mother, Margaret, and Elsie’s other daughter, Cedar, are very different, reflective of these characters different levels of education, the different company they’ve kept, underlining one of the book’s most salient points: the two people can come from the very same place and each turn out so differently. That what’s easy for one person might prove impossible for someone else.

So no, the plot doesn’t zip, but perhaps the ploddingness is not an accident, especially when you consider time from the perspective of a character counting the days since the last time she got high, or from that of a woman who’s counting down the days until she gets out of jail, trying (and failing) to overcome her violent impulses. Life itself is hardly deftly plotted, which might be the point of the entire book. Instead, it can be random, often lonely, and tragically unjust, especially for those who are marginalized.

October 6, 2021

Apples Never Fall, by Liane Moriarty

Liane Moriarty is a master of fiction, her genius undermined by her popularity, which makes many readers suspicious. Because how good can a writer possibly be if her bestselling novel gets made into a series by Reese Witherspoon and Nicole Kidman? A question to which I reply: she is so good. Truly Madly Guilty and Big Little Lies are both fantastic novels weaving BIG PLOT with the most sophisticated characterization, her fictional people complex and multi-dimensional, revealing their secrets in rich and surprising fashion which means the plot twists generally deepen the story instead of undermine it. I LOVE HER. The plots themselves undeniably frothy and too much, but in the best way, anchored by the human people at the heart of them. And her latest, Apples Never Fall, does not disappoint.

Which is a relief, because her previous novel, Nine Perfect Strangers, arrived as a bit of a letdown, Moriarty having come up with a fantastic cast of characters, each with luscious backstories, but it all failed to coalesce with an over-the-top preposterous plot and would have made a better short story collection. Because the trouble with a novel about perfect strangers is their lack of connection to each other, which is the kind of spark that lights the fuse.

In Apples Never Fall, however, she’s made her characters a family, which means there are sparks aplenty, decades of grudges and misunderstanding. Joy and Stan Delaney are celebrated tennis coaches whose own children were raised in an ultra-competitive, high intensity atmosphere, each of whom knows they’ve proved disappointments in their own special way. And when Joy suddenly disappears and Stan appears to be the prime suspect, each is afraid to voice their suspicions for fear they might be true.

It gets worse—detectives find a t-shirt soaked with Joy’s blood. Stan is becoming more and more difficult. There there is the matter of the curious house guest, a wayward girl who’d stayed with Joy and Stan after fleeing an abusive relationship a few months before whose story is not quite what it seems. Each of the four Delaney children suspicious of their father, but also each other, and wondering what else they know about their family might turn out to be founded on a lie?

I liked this novel so much for the way it complicates all kinds of ideas about family, marriage, truth and lies, about domestic violence, and anger, and the ways in which we know and fail to know each other. I love how each twist had us understanding these characters on an even deeper level, and how these twists also demonstrate what these characters don’t even know about themselves. And I love how all the threads come together at the end of the book in a way that was surprising, and even refreshing, such a perfect culmination of a most enjoyable read.

September 30, 2021

Fight Night, by Miriam Toews

Nobody in any of Miriam Toews’ novels is ever any good at being anybody but the people who they are, which are people who are so achingly real, human, complicated, messy, furious, alive. It’s also impressive that while Toews returns to the same themes over and over in her work, in particular the experiences of contemporary secular Mennonites, she never writes the same book twice, pushing the limits of point of view and just what a novel can possibly contain, and her reader gets the sense that she’s actively resisting anything close to boredom. Which means her books are never boring, even if—as is the case in her latest, Fight Night—not much actively happens in the way of plot at all.

But no matter. Who needs plot when you’ve got voice? And to that end: meet Swiv, whose point of view propels Fight Night from start to finish, a Toewsian voice if there is such a thing. A young, precocious misfit who is wise beyond her years, Swiv had been kicked out of school for fighting and spends her days with her eccentric grandmother watching Call the Midwife while her very pregnant mother, an actress, rehearses for a play. Swiv’s aunt and grandfather have both died by suicide, and she’s concerned her mother is headed for a similar fate, all the while she’s terrified her grandmother might pass away at any being, kept alive as she is on a cocktail of various medications.

The novel’s structure is a letter Swiv is writing to her father as she anticipates the birth of her new sibling and also her imminent abandonment by everyone she loves. She doesn’t actually know where her father lives. Swiv is terrified, and taking responsbility for all the adults in her life who are being overwhelmed by their own burdens.

And have I mentioned that the novel is terrifically funny? If you’re familiar with Toews, you’ll already know that. The gap between the world as it is and how Swiv’s sees it is very funny, as is her fierce dignity, and her prudishness in contrast to her ribald grandmother who gets quite a kick of mortifying her. But of course, (and if you’ve read Toews, you’ll know this too) it’s also heartbreaking, especially that this young person is carrying the entire world on her shoulders.

So there is laughter, yes, and there is crying. There is life, and there is death. There’s also a trip to California, a perilous plane journey home, Jay Gatbsy perpetually knocking at the door, busses and boats, and books sawed in half so they’re easier to hold. There is love and there is rage and there is ferocity and gentleness, and so many ways to keep fighting, so many reasons to fight.

September 15, 2021

Beautiful World, Where Are You

It’s been more than two years since I read Normal People, and even more since Conversations With Friends (which I wasn’t crazy about, didn’t live up to the hype for me) so I can’t remember if all Sally Rooney’s novels have reminded me of Virginia Woolf, but Beautiful World, Where Are You, her latest, sure did. The curious omniscience, the sea, the tide, the house, echoes of Chloe and Olivia… It’s a strange and demanding novel, really, and so intense. I wasn’t really reading it at first with the appropriate amount of focus, and it was hard to get into. There’s nothing light and breezy about it with its lack of breaks for dialogue and paragraphs, and the density of the narrative as well, capturing every little detail of modern life for these twenty-somethings in contemporary Ireland.

Alice and Eileen are friends, and Alice, who has just published two successful novels and become a publishing sensation, is living alone in the countryside, she and Eileen writing each other long and involved emails about their daily lives, about the men who are their preoccupations—Alice has a strange connection to Felix, a working class local she met on Tinder, and Eileen is infatuated with Simon, an older family friend who she’s known her entire life who sometimes she sleeps with, sometimes even when he has a girlfriend. There’s also a whole lot that goes unsaid between the friends, or unconsidered (the email chapters are broken by chapters with the four characters going about their daily lives) which is a strange thing considering how no one ever shuts up.

The exchanges between Eileen and Alice are heavy, as their consider the prospect of societal collapse, and the meaning of life, or if there’s even such a thing, and I honestly found it all very stressful at first, just because I worry about this stuff all the time and I don’t really need literature that leads me deeper into my worst anxieties. But also the narrative is wholly engaging—as I’ve written in other posts, I’m so profoundly not interested in many contemporary novels featuring bored and detached protagonists where there really isn’t any meaning at all. There is a heart and soul to this book, even with its navel gazing consideration and preoccupation with minutiae. Things matter. Life matters. Friendship matters, and in fact it may be that the connections between us are all that matters—and I loved this as a revelation. How subversive in our age of cool detachment to even venture such a thing, but Sally Rooney’s already mindblowingly popular so the haters are going to hate, so why not just go all in on the feeling. Which is not sentimental, I mean, if sentimental is a bad thing. If sentimental means slight or shallow, because there is substance here, truth and beauty.

Turns out I loved this book a lot.

September 3, 2021

Householders, by Kate Cayley

I was a big fan of Kate Cayley’s How You Were Born in 2015, and have been looking forward to her latest release, the short fiction collection Householders, which is out this month from Biblioasis, and it didn’t disappoint in the slightest. The first story, “The Crooked Man,” literally took my breath away, a story of overwhelming motherhood, family life in the city, and violence on the margins of everyday experience, and a similar ominousness infuses all the stories throughout the the rest of the collection. That no matter how much we try to hunker down in our houses (whether they be a Toronto semi, a bunker during the zombie apocalypse, or a commune in rural Maine), the world creeps in, and we can’t stop it.

The stories are loosely connected, the narrative about the commune in Maine serving as an anchor. Carol and Nancy arrive there in the late 1960s, and Nancy stays, becomes Naomi, falls under the spell. Naomi’s story and that of her daughter are woven throughout the rest of the book, right up to the present day, amidst stories of a man who offers mercy (or is it?) to a legendary musician past his prime; a woman who pretends to be an nun online; a woman reflecting on a strange and complicated relationship with a troubled woman she’d known during her university years.

Kate Cayley is splendid in her deft arrangement of the sentence, and in her depiction of the quotidian but just askew enough to be new and surprising. These stories are rich, absorbing, and oh so satisfying, and I predict this as one of the big books of the fall literary season.

August 23, 2021

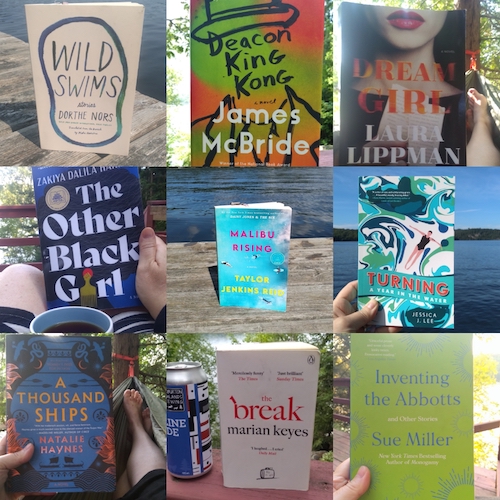

Holiday Reading Part 2

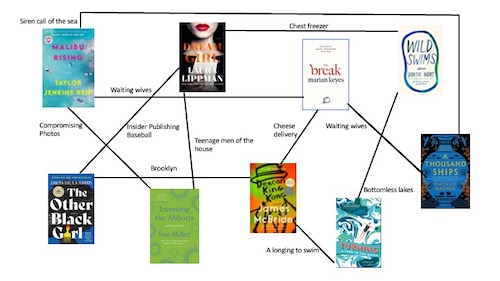

There were no duds in this stack, and even the title I was most intimidated by (hello, novel about the Trojan War!) blew me away. Every single one of these very different books was an absolute stunner, and the connections between them (as always!) were fascinating—see chart below. I was also so happy to reread Turning, which I’d read on vacation three or so years ago, and which I enjoyed but found so SPECIFIC that I wasn’t quite sure it would resonate again, so I gave it away, which I regretted for years. A new copy found its way back into my life this year, however, so I was happy to read it again. By a lake, of course.

I LOVED Malibu Rising—while I liked her previous novel, it didn’t quite live up to the hype for me. This one, however, was amazing. Every Sue Miller book I read is a pleasure. The Laura Lippman book was the most wonderful mindfuck, as was The Other Black Girl, both of which take on writing and publishing. Happy to read my second Marian Keyes—she’s really so good. A Thousand Ships was incredible, and Stuart and Harriet both devoured it after I did. Wild Swims was weird, but neat, and short, which is just the kind of portion I can take my weird in.

And finally Deacon King Kong, which I heard of somewhere, and then found in a Little Free Library shortly thereafter. It was rollicking, kaleidoscopic, huge in its scope, and tragicomic brilliance. Absolutely amazing.

August 13, 2021

Steadily Outward

“After all this exploring, we should be gazing steadily outward, beginning to find others again, and the brilliance of the world outside our doors.” —Julia Baird, Phosphorescence: A Memoir of Finding Joy When Your World Goes Dark

(I loved this book so much!)

August 6, 2021

Everyone in this Room Will Someday Be Dead, by Emily Austin

I will confess to having very little interest in all the sad, languishing literary heroines, the kind who embark upon years of rest and relaxation, spending entire chapters imagining what it might be like to have a job, asking such questions as, “How should a person be?” These literary people are just not to my taste, and so I was wary of Emily Austin’s debut novel, Everyone In This Room Will Someday Be Dead, about Gilda, who is overwhelmed by depression. And also a lesbian atheist who accidentally gets hired as a receptionist at a Catholic Church, and Gilda deals with this complication as head-on as she tackles everything in her life, which is to say: not at all. There’s also the mystery of her predecessor, an elderly woman whose death was suspicious. And the question of how many dirty dishes she can store in her closet before she’s forced to run some water in the sink.

I loved this book, which is very much internal, but where all the sad, languishing literary heroines are impossible company, Gilda is delightful. Her point of view entirely sympathetic, and the reader begins to cheer for the ER staff who receive her with tenderness as she arrives again and again with issues relating to anxiety. The whole narrative gets a little too madcap and threatens to go off the rail in places, but it holds steady, as Gilda doesn’t, and her despair has real resonance, her grappling with meaninglessness so meaningful, and yes, this is a book that ends with hope, which is definitely why I like it so much. But it’s also a really compelling depiction of the experience of mental illness, which was important to Austin, she writes, so that some readers will finally see themselves and that others might finally understand.

July 30, 2021

Summerlong

Summer continues! We had a lovely long weekend on Lake Huron recently, and I brought ATTACHMENTS, the first novel by Rainbow Rowell, and loved it so much. I’d had a rough week before we’d headed out of town and so even though I’ve gathered a pile of newly-released thrillers, I knew I wanted something more cheerful. The Rainbow Rowell book was not immediately appealing, however, because I’d found it in a Little Free Library and someone had spilled water on it once upon a time, but it turned out to be perfect, and now I keep recommending it to everyone. Such a great book that manages to be about work and friendship AND a romance all at once. It definitely brought back memories of nascent online culture in the workplace circa 1999/2000. Remember when your emails used to get flagged for using certain language? I worked in an office once where I inadvertently downloaded something that turned my cursor into a fairy wand, and somehow the IT guy knew immediately, and it was very embarrassing, and we didn’t end up dating, but they do in the scene from my next novel that I created out of this situation.