September 26, 2023

The Observer, by Marina Endicott

Tomorrow night (Wednesday September 27) I’m appearing in Hamilton with Marina Endicott as part of a fundraising event for the Hamilton CFUW with an author talk and live music. Books will be for sale and available for signing after the event. Tickets are $15, support the CFUW scholarship fund, and on sale online or at the door! Buy yours now!

(I was also fascinated to see that, in both our novels, somebody cooks eggs that nobody ends up eating and which sit for too long before they’re finally thrown out…)

*

Oh, how I loved this quiet, meditative book, which was not about quiet or meditative things, but instead about violence, abuse, trauma, PTSD, deprivation, loneliness, and LOVE. A novel that doesn’t try to explain, just the facts, ma’am, but between the lines lies such depth and heart-wrenching emotion, with such beautiful prose floating right on the surface: “Does someone teach us to see beauty, or does the world show it to us all the time?”

It also just sparkles with its depictions of the rituals and rhythms of ordinary life, all the waiting, and enduring, and surviving. (“Not one to go to pieces, Kendra had brought a spinach dip in a bread bowl.)

The Observer is a fictionalized story of the Endicott’s own experiences as an RCMP spouse in rural Alberta, her protagonist, Julia, a playwright who arrives in Medway with her partner Hardy, an outsider in every way, but she receives a particular vantage point working for the local newspaper, from where the novel gets its title, and the novel is indeed her observations with minimal editorial, and her keen eye gives us a vibrant sense of the community, for better or for worse, and these stories of particular people because of a treatment of people in general, of society, of humanity: “But I needed more information, more data—not for gossip, but to understand Hardy’s situation and my own, to understand and choose how to live my own life.”

The Observer would make a really interesting companion to Kate Beaton’s Ducks, a different kind of story about rural Alberta, about being an outsider, about work, and male dominated fields, and violence, and loneliness, and such environments are bad for women and ultimately bad for everybody.

It’s a novel about light in the darkness (literally—its opening image is that of a comet), of being soft and porous in hard place, about hope amidst the harshness of reality, and about how sometimes all it ever takes to keep going is the miracle of *just one good thing.*

September 25, 2023

Doppelganger, by Naomi Klein

I first found out about the Naomi problem in 2019 when I read No is Not Enough: Resisting the New Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need, and my best friend was horrified, and I was confused about why she was horrified, and then when she figured it out, she told me to google “Naomi Wolf” and “chemtrails,” so I did, and finally understood, or at least kind of, because what actually explains what happened to Naomi Wolf?

And so that question, “Whatever happened to Naomi Wolf?” is something I have periodically wondered about ever since then, the question becoming more and more relevant as Wolf’s own influence grew and the stakes got higher, as she spouted Covid misinformation through 2021 and onward. A question that seemed also relevant as so many apparently intelligent and curious people disappeared down conspiracy rabbit holes (ie the UK book blogger DoveGreyReader who went full QAnon before disappearing from the internet altogether, or the bestselling Canadian historical fiction writer who, as of Saturday but not thereafter [once someone had flagged it in their Stories], was following something called Gays Against Groomers on Instagram).

Last week was a fascinating time to be reading Naomi Klein’s latest, Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World, which is a consideration of “No Logo” Klein’s own personal branding problem as she has frequently been confused with Wolf over the last decade or so, but also an investigation of how the trajectory of liberal-darling turned far-right poster-child Wolf has a lot to teach us about radicalization, misinformation, political stratification, and the failures of political systems of countries like Canada and the US whose vacuums bad actors like Wolf and her comrade Steve Bannon, and so many others have rushed to fill. [Please note that I called referred to Wolf as “Klein” throughout this whole paragraph, and just had to go back and change it. The struggle is…weird?]

Last week was a fascinating time to be reading Doppelganger because the Mirror World of conspiratorial thinking was front and centre after supposed “parents rights”/anti-LGBT protests across the country on Wednesday that really were Convoy 2.0 with the same PPC signs and Fuck Trudeau flags (and I fear that well meaning people responding to these ding dongs with sincerity and heart are letting conspiracy nutjobs set the rules of engagement, like, it’s only a “culture war” if the other side mobilizes right back, playing right into their hands, which is exactly what they want, especially *play,* it all being just a game to these people anyway, rather than any of their ideas being worth responding to with consideration and logic. It is not irrelevant that, as Klein notes in her book, Steve Bannon dreamed up his ideas for world domination during a period in which he was working for an online gaming company)

In Doppelganger, Naomi Klein comes as closer as I’ve ever seen anyone come to explaining just what the heck is going on here, connecting the dots on a vast canvas, making sense of the nonsensical, in a way that will be familiar to anyone who’s read Klein’s work before, but also weaving in elements of memoir that are new to her work and which add a real sense of humanity to these stories in which so many of our fellow humans have come to seem almost alien.

Because of this book, I think I know finally (kinda, sorta) understand what was happening at the house I drove by in Norfolk County during the summer of 2022 that was flying a swastika out front, apparently a protest of the federal government. An anti-authoritarian protest that has one running authoritarian propaganda on one’s flag pole, the guy who hates Nazis so much that he’s appropriated their symbols, which is how it happens in the mirror world.

Doppelganger is a study of doubleness, and doubles—Klein and Wolf; left and right; self and avatar; who Wolf was and who she’s become; of how each “side” in this situation is imagining the other is living in a crazy dreamworld; of Israel and Palestine; of foundlings and how some parents of autistic children describe their offspring in similar terms, seemingly “normal” children replaced by another; about how so much far-right rhetoric employs language and ideas from progressive causes and can also thereby render language as meaningless. She writes about buffoonish monsters like Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, and even Putin, and describes “pipikism”—a term borrowed from a Philip Roth novel—”the antitragic force that inconsequencializes everything—farcicalizes everything, trivializes everything, superficializes everything.” She writes, “It doesn’t just farcicalize what they say; it farcecalizes what many of us are willing and able to say afterward.”

But of course any mirror is not just about its reflection, but also about what it tells us about ourselves, and Doppelganger is also a fascinating self-examination, as well as an actually kind and sympathetic study of what might have happened to Wolf and what particular aspects of her character make Klein a bit uncomfortable for what they suggest about Klein herself (and the last chapter, in which Klein describes them meeting in the early 1990s when Klein was a reporter for the University of Toronto’s student newspaper, The Varsity, is generous, weird and extraordinary). She also makes clear that social movements are the way out of this mirror world nightmare we find ourselves in, acknowledging that some conspiracies are indeed quite real (ie disproportionate power in the hands of a few unelected dudes who have too much money, for example) and showing that collective efforts are the only way to meet the pressing challenges of future (ie climate change, fear of which is provoking all this terror in the first place, such refusal to look reality in the face).

“Calm is resistance,” Klein writes in Doppelganger, quoting John Berger’s response to her earlier book, The Shock Doctrine, and I thought about that line too in the context of last week’s hateful demonstrations, how responding to panic and terror with panic and terror is simply a perpetuation of a narrative I don’t want to be a part of.

“The effect of conspiracy culture,” writes Klein in her new book, is the opposite of calm; it is to spread panic.” In Doppelganger, Klein suggests a deeper, more thoughtful way of acting (and thinking) in response.

September 19, 2023

Gin, Turpentine, Pennyroyal, Rue, by Christine Higdon

Christine Higdon has followed up her award-winning debut with the most extraordinary new novel, Gin, Turpentine, Pennyroyal, Rue, a book that somehow manages to be everything all at once: action-packed, artful, playful, timely, timeless, weighty, light, compelling historical fiction that maps so beautifully onto right now. Set in Vancouver in the 1920s, it’s the story of the four working-class McKenzie sisters and their supposedly divergent paths over the course of a year—infertility, pregnancy, an illegal and nearly fatal abortion, and a lesbian relationship–and how these paths are not divergent at all, but instead irrevocably connected to bodily autonomy, choice, and women’s liberation. The 1920s’ backdrop is fun and compelling, but the glitter stark against the darkness of what came before—the sisters watched loved ones return from WW1 with minds and bodies broken, or else not return at all; their brother dies in the flu pandemic; their mother is depressive and addicted to opium. The novel moves between their points of view, including the secrets they keep from each other, with a sweep that’s at once both intimate and cinematic, the narrative held together by an omniscient beagle (of course). A truly brilliant literary (and feminist) achievement, and just a wonderful read, I loved this book so much!

August 23, 2023

Another Week in Paradise

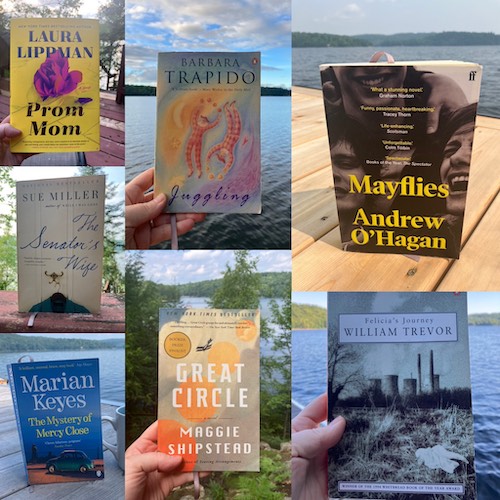

A+ vacation reads last week. Laura Lippman never disappoints. I LOVE Sue Miller and am reading through her backlist; this one was my favourite Marian Keyes novel I’ve ever read, about a depressive Private Investigator trying to find a member of a reunited boy band all the while experiencing suicidal ideation; my fourth Barbara Trapido novel, a contemporary story told in the fantastical structure of a Shakespearean comedy; THE GREAT CIRCLE, which I did enjoy but skimmed in parts; Andrew O’Hagan’s truly beautiful story of lifelong friendship; and William Trevor, William Trevor Forever! I love him.

August 10, 2023

Morse Code for Romantics, by Anne Baldo

I was soliciting picks for 49thShelf’s Summer Books lists when Stephanie Small from The Porcupine’s Quill got in touch. “It might not look like one from the cover,” she wrote, “but actually, I think Anne Baldo’s Morse Code for Romantics makes a good summer read,” which is an understatement if I ever heard one. For this is a book that is so steeped in summer, a collection of stories with sand between their toes, set along the shores of Lake Erie, scrappy cottages and rundown motels. With lines like “We don’t know it yet but we will never be bigger, or more real, than we are right here this summer. We will keep fading and shrinking, in small ways, forever always, after this.”

For the most part, these are standalone stories—the exceptions are a handful in which characters reappear—but they’re linked by geography, by recurring imagery, and themes which make this collection such a satisfying book. They’re linked too by being crafted to a standard of real excellence, and I’m thinking of the image on the book’s cover, of the power lines connecting the utility poles, without which I’d probably be employing a metaphor right now along the lines of beads on a string, one gleaming gem right after another.

These are stories of working class people, of people who’ve dropped out of the working class, of Italian-Canadians in the Windsor region. Most are fairly contemporary, the exception being “Marrying Dewitt West,” about the arrogant 19th-century naturalist investigating reports of a sea monster in the depths of Lake Erie who becomes the object of a wily young woman’s affections. And the sea monster image occurs also in “Monsters of Lake Erie,” which begins with an explanation of sonar equipment used in attempts at detecting the Loch Ness Monster: “I thought when you had been lonely for a long time you gained a similar sort of ability with people. To look at them, beaming out a silent pulse, and be able to glimpse the dark, monstrous shapes of their own loneliness lurking underneath the surface.”

There are a lot of lonely people and dark, monstrous lurkings in Morse Code... But peonies too, and shimmering light, a daring to hope, to dream. Magic and mermaids—”But people always forget that mermaids are monsters.” Sparks and fire.

August 8, 2023

Yellowface, by R.M. Kuang

So, I can’t say I’d necessarily recommend R.M. Kuang’s Yellowface to anyone else who has a new novel coming out in 28 days, because it’s just a little too on the nose, a satire that’s so real about the pressures and cutthroat competition of the publishing industry, the high stakes and low odds which “have made it impossible *for white and nonwhite authors alike* [emphasis mine] to succeed…” (to quote from the novel’s white narrator, who steals a manuscript from her dead friend, an Asian-American bestselling novelist, whose CV is not entirely distinct from that of R.M. Kuang herself—there are so many complicated meta-layers of to this work!). Mostly though, what a white author who sees her own experience in this novel is quite likely to miss is that Yellowface is also a satire of the way in which white women are able to put themselves at the centre of every story, wholly accustomed to being “the expected reader” (to borrow a phrase from Elaine Castillo) of every narrative they encounter, and oh, Kuang plays some tricks with that tendency with both her characters and readers alike. Edgy and brilliant.

August 3, 2023

The Damages, by Genevieve Scott

So just say you wrote a novel about the toxicity of sexual politics in the 1990s with a campus setting, a novel with duel timelines, the contemporary story set against the #MeToo movement as the protagonist grapples with allegations of sexual misconduct against her former partner, the father of her child, and the allegations and their fallout stir up memories of a catastrophic event on campus more than two decades before during which the protagonist’s roommate went missing, creating a fallout that left the protagonist’s reputation in ruins and trauma she’s still just beginning to process…

Wouldn’t it be SO ANNOYING when Rebecca Makkai’s smash hit I Have Some Questions for You comes out just months before your pub date?

A novel whose description so uncannily matches your own (there’s something in the water!) and whose enormous success could possibly overshadow your own?

Thankfully, however, there is this: If you liked I Have Some Questions for You (and a lot of people did!), you should definitely pick up Genevieve Scott’s The Damages. And there is also this: The Damages is not derivative in the slightest and turns out to be its own specific literary creature, a book that held me rapt throughout, and also doesn’t suffer from the overstuffedness that weighed down Makkai’s book at times (though I ultimately felt that the overstuffedness of IHSQFY was deliberate, the point).

The Damages takes place at a fictional version of Queens University in the winter of 1998 during a devastating ice storm that cut off power, caused vast damage and left people stranded throughout the northeast of North America. The novel’s narrator is Ros, who’s trying hard to fit in during her first year at university and who is eager to distance herself from her earnest and wholesome roommate who is the antithesis of cool. But when her roommate goes missing during the chaos and upheaval from the storm, everybody around her declares Ros responsible for what happened, and this shatters the tentative place she’d made for herself in that community, leading her to drop out of school.

22 years later, set against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic, Ros and her son are isolating in Ontario’s cottage country as she’s also processing allegations publicly made against her ex-partner, a renowned children’s author. She’s forced to finally reckon with notions of her own culpability, her responsibility, and the possibility that perhaps she’s been a victim too. As with the best books inspired by #MeToo, she doesn’t come to neat conclusions, but instead engages with the mess of it all, teasing out the multitudinous threads, asking questions instead of claiming to have all the answers. A terrific read.

August 2, 2023

Wait Softly Brother, by Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer

The pieces of Wait Softly Brother—a novel about a writer called Kathryn who retreats to her childhood home in Ontario’s Hastings County after fleeing her marriage, she and her aging parents in a relationship of mutual irritation as she pesters them for details of her brother, stillborn before her own birth, desiring some kind of fragment to make the fact of his existence feel tangible, but her mother hands her a letter from a long ago ancestor instead who fought in the Civil War, Kathryn making up HIS story instead as a way to interrogate maleness and brother, and missing pieces of a whole, all the whole torrential rain is falling for weeks and weeks, the family farmhouse an island cut off from the rest of the world—culminate in the richest and most satisfying kind of story, a deep literary mystery. On dwellings, and dwelling, and wells and welling. So so excellent.

July 27, 2023

The Mythmakers, by Keziah Weir

Okay, hear me out: Lily King’s Writers and Lovers meets Meg Wolitzer’s The Wife (which it directly references!), with a healthy and surprising sprinkling of astrophysics and consideration of the possibility of a multiverse. I LOVED this book, The Mythmakers, the fiction debut by Keziah Weir, a senior editor at Vanity Fair (who has British Columbia ties, so the book gets to be Canadian!). It’s about Sal, a struggling magazine writer whose life has just imploded and who is surprised, no, perhaps enchanted, to find herself within the pages of The Paris Review as a character in a story by an older author she’d met at a book launch years before. But then she reads the story’s introductory text to discover that the author, Martin Scott Keller, had recently died, and also that the story is an excerpt from his final novel, a long-awaited text. Well, naturally, Sal wants to read the rest of the story, and concocts a scheme wherein she connects with his widow under the guise of writing a magazine piece about the experience of discovering herself in fiction, but then the story becomes more tangled than that, too tangled for magazine piece, even long-form.

The Mythmakers is rich and absorbing, a fast gripping-thrill, but also deeply literary, about the nature of story and storytelling, and also the nature of the universe, and of marriage, and love, and the way myths—in particular that of the male genius—are propagated and upheld. It’s a story about art, and art-making, and science, and sexual politics, and gender, and it’s also slightly uncanny, it’s narrative voice hard to pin down, sometimes Sal, sometimes Martin, or Moira, his wife, but is it really?

Who’s telling the story? Who’s pulling the strings?

July 26, 2023

Girlfriend on Mars, by Deborah Willis

The premise sounds like a gimmick: Kevin is a failed screenwriter who now ekes out a vague living as a film extra while growing pot in his Vancouver basement apartment, the enterprise—until lately—overseen by his highly capable girlfriend, Amber, the two of them a couple since high school, after which they managed to escape the confinements of their hometown in Northern Ontario (as well as Amber’s dashed dreams of Olympic glory after an injury ends her gymnastics career, the freight of her evangelical upbringing, and Kevin’s overbearing troubled mother) for a new life on the west coast. But that new life never proceeded according to plan, and now Amber is gone, having won a spot on a reality show whose contestants are vying for a one-way-trip to Mars—and it turns out that Amber stands a mighty good chance of winning, of escaping Earth and all the doom inherent in its future. And escaping Kevin too, but he’s just not willing to give up on her yet.

Girlfriend on Mars—Deborah Willis’s first novel following her Giller-longlisted story collection The Dark and Other Love Stories—is really funny, a whip-smart satire, and also intensely moving, even in its more ridiculous moments, because these characters caught in an awfully silly situation have arrived on the page with perfectly tuned back stories providing real emotional heft to a story that otherwise might be so light as to be weightless. This was a story that had me turning its pages with no idea how and where it might possibly end, and a little warily too because I worried these characters existential dread could be a trigger for my own anxiety, but it all came together in a way that was sad, gorgeous and perfect. I heartily recommend!