May 13, 2025

Favourite Daughter, by Morgan Dick

No one’s got their shit together in Morgan Dick’s debut novel, FAVOURITE DAUGHTER, the story of two women who share a father but who’ve never met each other. When her estranged dad dies, Mickey learns that she’s to inherit his estate with one proviso: she must complete seven sessions of therapy. And when she walks into the therapist’s office, it’s Arlo she encounters, her father’s other daughter, each woman with no idea who the other one really is, or that they have a connection at all. Which means that Arlo is technically violating no ethical guidelines as she takes on her sister as her patient, but maybe there is something to the sibling dynamic and boundaries have never been Arlo’s strong point anyway, years of trying to save her alcoholic and disappointing father leaving her prone to becoming tangled up in other people’s messes, and soon the siblings are as complicatedly invested in each other as true siblings can be.

Although even without the genetic connection, Mickey would be a formidable challenge to a therapist. The centre of her world is her job as a kindergarten teacher, a job that gives her life shape and meaning—she’s been cut off by her mother, and doesn’t have any friends—but a bad call on the job and the fact of her drinking means that Mickey’s job might be taken away from her forever. After years of addiction, can Mickey finally make meaningful change in her life? And how different is she from Arlo anyway, who appears put together on the surface but whose security is just as fragile as Mickey’s is, and who has made her own mistakes? Or the very slutty lawyer, Tom, who’s settling their father’s estate, or their long-suffering mothers, or Mickey’s very weird neighbour with the luxury cat?

Each of them is a complete and utter mess, and yet also sparkling with some goodness, and wholly worthy of love, which is the charm of this novel, which is sometimes sad, sometimes deadpan, and ever surprising.

May 7, 2025

A Mouth Full of Salt, by Reem Gaafar

Reem Gaafar’s debut novel, A Mouth Full of Salt, 2023 winner of the Island Prize for a debut novel from Africa (and the first book by a Sudanese writer to be recognized by the prize) grips the reader from its opening line, “Until a body was actually found, they referred to him as ‘missing.'” The body in question is that of a young boy presumed drowned in the Nile, a too frequent incident among the people from his village: “The Nile was a trap that attracted, ensnared, and buried all at once. It took from them as much as it gave.” Which what happened to Fatima’s brother after all, years earlier, a tragedy from which her mother has never recovered, leaving her a little outside the local community of woman, and this Fatima can relate to. She too is also set apart from her peers, although this is by her determination to pursue her education, as opposed to her good friend Sawsan, whose wedding is approaching.

A Mouth Full of Salt moves between Fatima’s perspective and that of Sulafa, the mother of the missing boy, whose been relegated in her household after her failure to have more children, and whose husband’s second wife is currently pregnant with twins. As the villagers keep watch for the boy’s body to resurface, other catastrophes beset the village one-by-one: farm animals are struck by an illness, and die on mass; fires take down gardens and orchards. Villagers are talking about prophecies, worry about a curse, and soon that something has gone very wrong for these people are altogether undeniable.

Like Sudan itself, this novel is cut in two, and in its second half, readers begin to understand how the nation’s history is at the root of what’s happening in the village. From the 1990s, we’re taken back to 1943 and to Nyamakeem, from the country’s south, who has fallen in love with Hassan, a northerner, an Arab. Such unions are rare and frowned upon, and Hassan is rejected by his family. The two of them attempt to build a life together in Khartoum all the same, raising their son, but when Hassan eventually stops coming home to them, Nyamakeem has no choice but to go back to his home village and his family to find out what happened.

How the lives of the women in this novel intersect is the crux of a taut and measured story. Gaafar, who now lives in Ontario, and is also a physician, has crafted a beautiful and compelling novel about women attempting to break free from the limits of their power.

May 5, 2025

The Cost of a Hostage, by Iona Whishaw

For the last few years, I’ve looked forward to a new Lane Winslow mystery novel in the spring like I’ve looked worked to forsythia blooms and cherry blossoms, and just like spring herself, author Iona Whishaw has never failed me. The Cost of a Hostage is the twelfth instalment in her series about the brilliant polyglot whose wits are only matched by her beauty and whose desire for a quiet life in the small community of Kings Cove, outside Nelson, BC, is thwarted by her tendency to stumble upon dead bodies and wander into crimes in progress. Thankfully, however, nobody is better equipped to solve these crimes, much to the chagrin of local Police Inspector Frederick Darling, who eventually becomes Lane’s husband. Which means he often finds himself in fixes like the one that kicks of this latest novel: Darling’s brother has gone missing in Mexico, and has perhaps been kidnapped; is there any possibility that Darling can get to Mexico without convincing his dear wife that she’ll be just fine staying at home? The answer is, of course, no, and so off they go, which Darling is not exactly sorry for. Lane Winslow is surprisingly useful to have around, and besides he likes her company. Their marriage is a rare and beautiful thing in the late 1940s, an arrangement of equality, both partners ardent in their admiration and respect for each other’s keen intelligence (though Darling would admit that Lane’s is the keener one).

Anyway, staying home might not have been so quiet either, after all. When a small boy is kidnapped in Nelson, the circumstances are curious, and Ames and Terrell, running the Nelson Police Department in their boss’s absence, have their hands full solving the crime, especially once their chief suspects turns up dead in the local ferry’s paddle-wheel.

Once again, Whishaw brings her readers a story with fascinating moral complexity and a healthy dose of feminism and progressive values. And yes, just enough peril that you’ll be totally gripped.

April 30, 2025

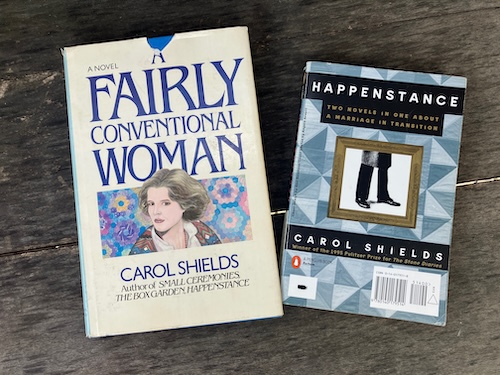

Next Up from Carol Shields

My Carol Shields reread continues to be very rewarding. And especially with her third and fourth (and kind of fifth) novels, which is where her novel writing really began to find its stride. While I enjoyed rereading Small Ceremonies and The Box Garden, especially for the Carol Shields-ness at the core of them, I could discern the effort it took to structure these books, like a kind of scaffolding beneath the surface. But with Shields’ third book, Happenstance, there is nothing but the art itself. Like, the training wheels are off, and there she goes, and this woman knows exactly what she’s doing now. And she’s going to keep on doing it—this is what also amazes me about these early books, the threads and preoccupations that will be picked up through the next two decades of Shields’ literary career.

If you buy a copy of Happenstance now, you will likely be purchasing the version of the book which is subtitled, “Two novels in one about a marriage in transition.” One side of it is Jack Bowman’s story, originally published in 1980 as Happenstance, and then flip it over to the over side to read a novel from the perspective of his wife, Brenda, published in 1982 as A Fairly Conventional Woman. As a Shields’ completist, I’m still looking out for an original edition of the former, but I found a first edition of the latter a couple of years ago that I was delighted to read this time. I’ve read both those books before, but don’t remember very much about them. As I’ve said with every Shields’ book I’ve reread so far, I don’t know that they’re written to be properly understood by anyone under the of 30. And it’s curious and interesting to be reading them now in my mid-40s, just a tiny bit older than her protagonists, just a little bit older than Shields was herself when she started to publish her fiction. In some ways, it almost feels like I’m meeting this author I’ve loved since I was young for the very first time.

I imagine that when I read the double version of Happenstance, I read Brenda’s story first, just because women’s stories are usually more interesting to me. But this time, because chronology, I started with Jack, and I actually think it’s a better novel than Brenda’s. I assume Shields wrote it first and Brenda’s later, which might explain it—the material was more fresh for me, she was inventing instead of filling in gaps and picking up threads. It’s also, counter-intuitively for a husband’s story, more concerned with the domestic, as it’s about Jack at home with his children while Brenda is on a trip to Philadelphia, and domestic details are always most interesting to me. All of my favourite books are about people at home.

When I interviewed the author Jenny Haysom about Carol Shields on my podcast last fall, I’d remarked that her novel Swann was something of a departure for her, being more concerned with academia than the domestic, but my rereading has proved that I was wrong wrong wrong. All Shields’ protagonists so far have been academic wives with connections to academia themselves—Charleen in The Box Garden ekes out a living editing a botanical journal affiliated with the academic institute her ex-husband was part of; her sister Judith, in Small Ceremonies, is a biography married to a university professor; and now Jack Bowman works as an administrator for “The Great Lakes Research Institute,” not an academic himself, just with an undergraduate degree, though he has been struggling to finish his book about Indigenous trading practices for years. (He’d met his wife, Brenda, when she’d been working at the Institute doing typing and filing, just out of secretarial school.)

It’s funny because I remember, when Larry’s Party was published in 1997, that there had been conversation about Shields turning her attention to the details of masculinity after The Stone Diaries, but Happenstance makes clear that the details of masculinity had been her concern for a long time. (There is also a character in it called Larry.) And such details also have not changed substantially in the 45 years since Happenstance was published. There is a lot of talk these days about manhood, and men’s relationships, and male loneliness, and Happenstance taps right into all of this. Every Friday, Jack Bowman has lunch with his friend Bernie (his one good friend, Bernie; “his one friend, Bernie?;”There must be a measure of failure, Jack supposed, in the admission that he had gone this far in his life, forty-three years, and achieved only one friendship”), an arrangement going back twenty years, the two of them choosing an all-encompassing topic (this year it’s “history”) and spending their time getting to the bottom of it.

Happenstance is a novel about ideas, about history, about time, about beginnings and endings. Its grasp of its current moment—Russian dissidents and Middle East ceasefires—reads very close to our own. As with Shields’ first two books (and everything she ever wrote?), it’s about the limits to what spouses can know and understand about each other. Also, like everything Shields ever publishes, it’s about what gets to considered important, entered into written record. (Which will bring us to Brenda’s story, but just a moment…)

The one part of this novel that is curious and possibly dated is a story line in which Jack’s eldest son seems to have partaken in a fast, echoing political hunger strikers who are currently in the news. It recalls the daughter in Shields’ last novel, Unless, who takes up residence on a Toronto street corner holding a cardboard sign that says, “Goodness.” This is unfathomable and heartbreaking to her parents, while Jack, in Happenstance, isn’t ruffled by it. He ends up talking to a doctor who tells him that Rob can live without food for a while, he’ll be fine. And then Rob’s younger sister is similarly inspired, and Jack decides that this is good news, because Laurie’s a bit fat anyway, and maybe this will finally be the end of that.

A weird note for sure, and the one on which A Fairly Conventional Woman begins. It’s the same Friday morning on which Jack’s story starts, and Brenda is making breakfast for her husband and children, but she will eat nothing herself. “She is watching her weight, not dieting, just watching. Maintaining.” And then a line about how she’s watching Laurie too, whose jeans no longer fit. Will Brenda too be relieved that their chubby daughter has taken up fasting? Brenda is slim, we know, although (and note that connections between these two ideas are never explored) her mother had been a size 22, and made all her own clothes. All of this making me think about The Stone Diaries, which begins with Daisy’s magnificently fat mother, and clearly fatness too (and maintenance!) had been a preoccupation for Shields, though ideas around bodies and fatness have changed so much since the 1990s, I can’t imagine how those parts of The Stone Diaries will read when I get to it. (Though I am sure that not so much has changed that there won’t be parents out there somewhere relieved that their fat daughters have taken up fasting…)

Anyway, Brenda—a daughter, whose mother sent her to secretarial school, where she’d get the job where she’d meet the man who’d make her a wife—has lately taking up quilting, and it turns out she’s got a talent for it, and she’s invited to appear at a crafts convention where her work will be displayed. Finally, a something of her own, even though it’s a craft, instead of art—and the relegation of the former is made clear when the crafters are made to play second tier to a convention of metallurgists. One of the most fascinating parts of the book are chapters entirely in dialogue by Brenda’s peers at the convention. There’s also a wonderful scene where she buys a raincoat that’s far too expensive, but that she covets, and it reminds me of that scene in Unless (which also appears in an earlier short story) where a character buys a scarf, how a thing can satisfy. (Jack Bowman has doubts about thinginess in Happenstance, however. It’s what makes him suspicious of Brenda’s pursuits. He fancies himself as a man of ideas, elevated above mere objects.) AFCW is about women wanting, or how they don’t want often enough, their desires so often subservient to the needs and desires of others. The reader realizes that Jack Bowman is really wrong about his beloved wife’s inner life.

“What [Jack] didn’t seem to grasp (as Brenda did) was that history was no more than a chain of stories, the stories that happened to everyone and that, in time, came to form the patterns of entire lives, her own included.”

April 24, 2025

Restaurant Kid, by Rachel Phan

I was expecting…less?…from Rachel Phan’s memoir, Restaurant Kid. The story of growing up Chinese in a small town in Ontario, the experience of having the family business be the centre of domestic life, what it’s like having immigrant parents who give everything to their jobs in order to make enough money to give their children the kind of life they couldn’t have imagined growing up in in wartime Vietnam. I wasn’t expecting a memoir quite so intimate, so personal, and all-encompassing, but then I realized that this was the point—that where she came from would define everything for Phan. How she felt about her Chinese identity as a child in a community where racism was ordinary, how her parents were too busy to give her the attention she desired from them and so sought it elsewhere, how stereotypes of Asian woman would be part of her early sexual experiences, how her parents’ story would underline her own relationship with money and finances, and more. Restaurant Kid is capacious enough to hold Phan’s anger and resentment at some of her parents’ choices, but also her extraordinary love for them, and the sacrifices they made to give their children a life in Canada. I loved the whole book, but a particular highlight is the epic trip she takes to Vietnam with her parents once she’s in her 30s and her parents can afford to take time away from the business (which her brother runs now, a complicated inheritance, as most inheritances are). In Vietnam, she has the opportunity to see a different side of her parents, being at ease in their native tongue, at home and familiar even in this place that holds so many traumatic memories, and her ability to hold them and love in them in all their messiness and complexity is so extraordinarily moving. Which a rich and brilliant book.

April 18, 2025

The Float Test, by Lynn Steger Strong

I don’t know if The Corrections started it, but for a long time now, all books about unhappy families have been alike in a similar way. Grown children returned to the nest, long simmering secrets and resentments, neuroses and addictions, third person narratives moving between different perspectives, the inevitable blow-up, but THE FLOAT TEST felt like something different. It felt like more of a narrative tangle, a knot. The narrator is Jude whose mother has just died, a difficult and demanding woman, and part of the narrative trajectory is Jude and her three siblings unpacking their relationship with her, the cutting edge of her affection and attention. Although Jude does not make herself the centre of the story, that place belonging to her older sister Fred, whose story Jude “imagines herself into,” portraying moments and incidents she would not be party too. Which is interesting, because Fred is the storyteller in the family, a novelist who has helped herself to bits and pieces of other people’s lives, her family included, scattering these throughout her fiction, and also something has happened between Fred and Jude that isn’t clear. And the backdrop to all of this is Florida, where the family comes from, and to where Fred and Jude both have been loathe to return, where the vultures are circling, the hottest summer ever so everyone is dripping with sweat, and swimming is the only respite—the novel’s title comes from the test that Jude and her siblings were never able to pass because their talent has always been for striving, moving, winning, instead of stopping, floating, being. And there is something suspended about the narrative too, all of the siblings stranded in the in-between in various ways, except for these absolutely wrenching moments that hit on the complicated nature of love, how it can be riddled with pain, the impossible gnarl that is family and history and that place from which we come.

April 16, 2025

She’s a Lamb!, by Meredith Hambrock

Jessamyn St. Germain is bound for greatness, and her confidence is unshakable. Even though the discerning reader will swiftly note the gap between her self-perception and how the world receives her in Meredith Hambrock’s second novel, SHE’S A LAMB! (the title taken from a lyric in THE SOUND OF MUSIC’S “How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria,” “She’s a darling! She’s a demon! She’s a lamb!”).

Instead of receiving a role in a regional production of the famous Rodgers & Hammerstein musical, Jessamyn is offered the job of childminder for the show’s youngest actors, an offer she suffers with indignation until it occurs to her that it’s an opportunity in disguise, that surely the director has little faith in the actress playing Maria and needs to keep Jessamyn nearby so she can step into the role when the time arises and finally have her moment in the spotlight.

SHE’S A LAMB! has been compared to the novel MY YEAR OF REST AND RELAXATION for its portrayal of a heroine so stuck up on in her own head that she’s disconnected from the world around her, although I liked Hambrock’s novel so much more for its character’s fierce and ferocious need and desire. There is no such thing as rest or relaxation for Jessamyn, whose singular pursuit of her goals leads her down dangerous paths and is going to end up with a body count.

On one level, SHE’S A LAMB! is a very dark comedy of the absurd in which Jessamyn is willing to do anything to make her dream come true—and get rid of anyone in her path in the meantime. With remarkable restraint, Hambrock leans away any possibility of redemption and focuses her narrative just as narrowly as Jessamyn herself has on her own possibilities. The result is hilarious, ridiculous, creepy and chilling at once.

And chilling most of all for the parts of it that seem most familiar. While Jessamyn never doubts herself, she knows that everybody else around her wonders about their own talent, their own potential, their own destiny. ‘”You don’t know,'” she tells the actress playing Maria, the role she covets, undermining her confidence. ‘”You wish. You hope. But you don’t know. You can’t know. You can never know.”‘

It’s a terrifying message that will ring true for anyone who ever wanted to be anything.

April 11, 2025

Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, by Mark Bourrie

Imagine releasing a book about current events in 2025, the challenge of telling a story with everything so unstable and with no indication of how that story is going to end. RIPPER, Mark Bourrie’s new biography of Pierre Poilievre, the leader of the federal Conservative Party, is current right up until the beginning of February, which is less remarkable for a book that I’m reading in April than absolutely incredible. Although the one advantage that Bourrie had was that, while the world is unstable, ever-changing, plotted with twists and surprises, his biographical subject is much easier to pin down. The thesis of RIPPER is that Poilievre is the same person he’s always been, ever since he was Grade 9 student vying for a spot on the executive of Preston Manning’s riding association, attending seminars at the Fraser Institute, and—like many teens—being outraged about the capital gains tax.

Bourrie writes in his introduction: “Is he a bad person? I’m reluctant to make that claim. I think he’s an angry teenager in the body of a grown man. That makes him a stellar opposition politician. It is a bad combination in a prime minister.”

RIPPER is not just about one man, but also about the place he comes from, Alberta, which has always played an out-sized role in Canadian politics compared to other provinces, and Bourrie tells the story of Alberta’s booms and busts, its sense of grievance, and why The Reform Party would emerge from there in the 1990s to remake Canadian politics. Through his story he shows that someone like Poilievre—whose politics and character would have seemed strange and fringe as he came of age—has had mainstream opinion shift in his favour over the last 25 years, through the fall of traditional media, the rise of partisan pseudo-media, a decline in standards of living that suggests there might be something to his claim of Canada being broken (although this decline is a global one), a data-driven approach to courting voters (which lends itself to dirty tricks), and an attack-dog style to politics that’s embodied by Poilievre himself and the people he surrounds himself with.

Bourrie’s narrative voice is personable, engaging and authentic—he makes clear in his introduction that he is not anti-conservative, but that he’s opposed to what Conservatism has become, employing American-style tactics and unafraid of undermining democracy, wholeheartedly embracing the protesters who occupied downtown Ottawa for weeks in February 2022 whose plans were to overthrow the government. Bourrie’s story is fast paced, and gripping, and—with real restraint—not petty (not a word about Poilievre’s remarkable SHE’S ALL THAT-style makeover once he’d become Conservative leader). The book’s depth and focus—as with so many other books I’ve read lately which are most current in their approach—is most clarifying, helping me connect the dots in the chaos of our moment and recent history, making some kind of sense of it. (This is the kind of understanding that inoculates one against becoming a conspiracy theory nut-job).

Imagine releasing a book about current events in 2025, the challenge of telling a story with everything so unstable and with no indication of how that story is going to end. And then, imagine—even worse—not even trying.

Kudos to Mark Bourrie and his publisher Biblioasis for meeting this moment.

And everybody else: read this book. (And also read Catherine Tsalikis’s biography of Chrystia Freeland, who you might remember as the person who orchestrated any and every hope of the Liberal Party doing well in our upcoming federal election.)

April 7, 2025

Steamy: A Menopause Symptomology, by Susan Holbrook

My first child was born in 2009, which was the year that Susan Holbook published her collection JOY IS SO EXHAUSTING, a book bursting with life and bodily fluids. I felt so seen by her epic poem “Nursery,” twelve pages documenting breastfeeding from side to side: “Left: Now that you’ve started solids, applesauce in your eyebrows, I’ve become a course. Right: Spider on the plastic space mobile, walking the perimeter of the yellow crescent moon. Left: Dollop. Right: Now it’s on Saturn’s rings; if it fell off, it would drop right into my mouth. Left: I take 2%, you take hindmilk. Right: Fingers shrimp their way through the afghan holes. Left: I have hindmilk.”

And now that I am 46, constantly itchy and getting my period every nineteen days, signalling the beginning of my perimenopausal journey, Holbrook has delivered STEAMY: A MENOPAUSE SYMTOMOLOGY, a poetic memoir that’s hilarious and searing at once. The baby from “Nursery” is all grown up now (see Symptom 29, “Dry Eyes,” in which the grown child is dropped off at university, and the poet does not cry. “For most of my life you could count on me to descend into blubbery convulsions at a filmic dog death or an airport farewell or, of course, a real dog death. I would readily cry for sad or happy reasons any old time. Now you can rarely squeeze a sob out of me. Maybe I’ve used up all my tears along with my eggs.”) and the poet is contending with other changes (see Symptom 3, “Cessation of Menses”: “I’m not sure why I never went to the doctor./ Maybe because I was so relieved each time my tsunami ended that I didn’t want to think about it again until three weeks later when I ruined the *other* side of the couch cushion”).

Like the symptoms of menopause themselves, Holbrook’s symptoms can go off on a tangent and sometimes end up being about raccoons or the time she broke her arm at age 11, which I don’t mind in the slightest because, like menopause, this book is full of twists and surprises, and, unlike menopause, it’s also very funny and rich with meaning (see Symptom 33, “Reduced Libido” for former, which is mostly about her grandpa, and Symptom 30, “Panic Disorder,” for the latter, “A year later my heart dances with the daffodils. I found a drug that muffles my panic but not my joy.”).

April 3, 2025

How to Survive a Bear Attack, by Claire Cameron

I never read Claire Cameron’s 2014 novel The Bear. My kids were 5 and 1 when the book came out, and at the time (and even now) I felt far too tender to contend with a story in which parents are killed in a bear attack and their small children are left to fend for themselves in the wilderness. Not unrelated to the arrival of my children OR my aversion to reading the story was also an anxiety that had settled into my consciousness like a fug and years later would knock me totally flat. (It’s curious to read my first novel and see it there, when my protagonist takes in the big old trees in her neighbourhood, and how vulnerable she is to dangerous objects falling from the sky, how vulnerable even her home is, and that safety is an act of faith more than it’s ever a fact). But that same anxiety, which I’m learning to live with and understand better, was absolutely why I very much wanted to read Cameron’s latest book, the memoir How to Survive a Bear Attack. Because it’s a book about anxiety and fear, and living with them both, and the fact that maybe we’ll even be strong enough when we have to step up to fight, but we can’t plan these things, and the danger is never quite where we imagine it will be.

Cameron’s father died of skin cancer when she was nine-years-old, and in the years after, she found her way back to herself, and through the weight of her grief, by immersion in the great outdoors. She became an avid canoeist, wilderness trekker, rock climber, tree planter, finding solace in nature and wildness, and also power in her own strength and abilities to succeed at the challenges the wilderness threw up at her, including run-ins with bears. She even fancied that she’d know what to do if the unlikely event of a bear attack occurred. Such attacks were rare, but Cameron she was interested in stories of these outliers, like the Canadian couple killed in Algonquin Park in 1991. Understanding what happened to them became an insurance of sorts, because if she could just figure out what they’d done wrong and do it differently, then she would be fine. It was also gateway to her literary breakout, with her second novel’s great success.

But when the danger finally arrived, it came from a place that Cameron had never seen coming. At 45, she was diagnosed with skin cancer, and learned she had a rare genetic mutation making her especially susceptible. She was advised by her doctor that her optimal UV exposure was precisely none. Facing her own mortality brought her back to her memories of her father, a professor of Old English, and the stories he’d taught and shared with her of monsters and dragon slaying. She calls on his courage and strength to help get her through her diagnosis, and many surgeries, and also begins to consider anew the story of the couple killed in Algonquin Park all those years ago. What had she missed from the story the first time? What other lessons might there be? How was she to find her home in nature again when parts of her life she’d always taken for granted—paddling in the sunshine on a lake that reflects the light like a mirror, for instance—had suddenly become perilous. And what of the bear itself? Where, exactly, was the heart of this story?

I tore through this memoir in a day, absorbed by every thread in this multifaceted narrative. The bear stuff BLEW MY MIND and Cameron’s own journey is gorgeously and emotionally wrought, and I came away with just the kind of perspective I’d been hoping to get. “Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love.”