July 20, 2022

What Storm, What Thunder, by Myriam J.A. Chancy

In June, I attended the second of a two-night spectacular in downtown Toronto celebrating the works of Toni Morrison and Black women writers (and had even contributed a short written piece about Morrison in anticipation of the event!) produced by Donna Bailey Nurse who, that night, was interviewing Myriam J.A. Chancy, Aminatta Forna, and Dawnie Walton, and I purchased Chancy’s latest novel, What Storm, What Thunder, which I read it on holiday last week, and it really is the very best book I’ve read in ages.

To read this novel, set in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti that killed 350,000 people, is to feel humbled. By the power of Chancy’s prose, first of all (I couldn’t help but read aloud an entire passage about leatherback turtles hatching on the beach: “They’d survived the Ice Age, continental drift, volcanoes erupting below and above ground, asteroids. They were the first superheroes. All that, and still, like most things, they began puny and fragile, scared and scrambling.” SO GOOD.) Humbled also by how puny and fragile are the lives we build in contrast to the destruction the earth might yield, as it did on January 12 2010, buildings collapsing, thousands of people trapped beneath the rubble. And finally humbled by how little I’ve thought about the Haitian earthquake in the years since it happened—how easy it has been to have the stories of lives lost fly beneath my radar.

Chancy, who is Haitian-Canadian, was not in Haiti when the earthquake struck, but in the months and years that followed, as she travelled and campaigned for organizations supporting Haiti and its recovery, she heard so many stories of people who had been. “Listening for years, I realized later,” she writes, “was a big part of the process of writing this novel.”

And so, fittingly, this is a novel constructed of a variety of voices—Ma Lou, the old woman who sells fruit at the market; a young boy makes money delivering her produce to the fancy hotel where Sonia, who works as an escort, runs into Leopold, a drug dealer, just moments before the hotel collapses. The boy’s mother is Sara, left traumatized by the loss of her three children, and her desperate existence in a camp after her home is destroyed. Ma Lou’s estranged son, Richard, a wealthy executive of a bottled water company, has returned to his home country from Paris in hopes of outrunning his own demons. Sonia’s younger sister Taffia tells her story of life in the camps, where rape is a common occurrence and resources are scarce, donations from other countries inappropriate and useless. Taffia’s older brother Didier is living in Boston, driving a taxi without a license, and he experiences his country’s tragedy from afar. Sara’s husband Olivier has left Port au Prince to follow rumours of factory work in other parts of the country. And Richard’s daughter, Anne, an architect who works with NGOs, leaves her placement in Rwanda to come home and volunteer in the camps.

Chancy writes in her acknowledgements, “In the end, what I wanted to capture was the way in which lives were disrupted, what those lives may have been life, before, what might have remained after.”

What Storm, What Thunder is vivid, brutal, gorgeous, devastating, its pieces so artfully woven, its storytelling invested with immense beauty and power. Haunting and mesmerizing, it’s the novel I’ve been trying to urge everybody to pick up since I read it, an extraordinary testament to what fiction can be and do.

July 5, 2022

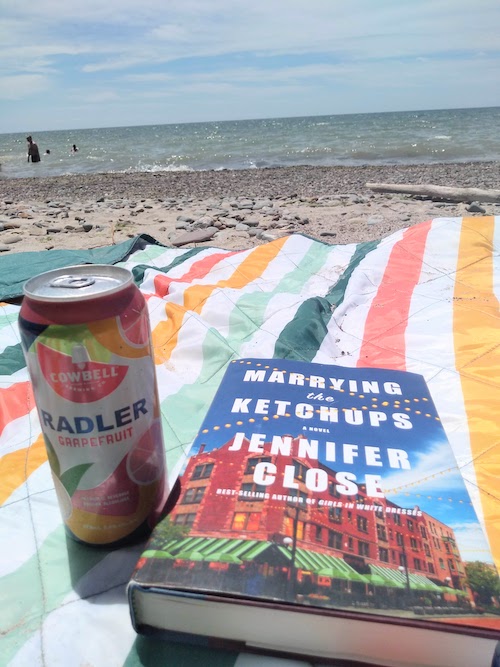

Summer Read Supreme

I’m happy to kick off my summer reading this weekend with Jennifer Close’s Marrying the Ketchups, which my friend Marissa recommended and which I loved so fully completely and devoured in a day. (Being able to read a novel in a day is my definition of a proper holiday, in addition to buttertarts.) I loved it so much, and it is the kind of book that, if a man had written, people would be heralding its emotional acuity and literary genius. Plus it was blurbed by Katherine Heiny and she was thanked in the acknowledgements, which is pretty much my literary catnip.

July 4, 2022

A Convergence of Solitudes, by Anita Anand

When I was on the radio last week talking about great books for REreading Canada, Anita Anand’s A Convergence of Solitudes was the one title I hadn’t yet finished reading, so I’m happy to report that I finished it this weekend and it lived up to my expectations and then some.

How do you tell a story that connections Quebec nationalism in the 1970s to the Partition of India in the 1940s, weaving in threads about Operation Babylift during the Vietnam War, colonialism in Ireland, and the experience of growing up as a person of colour in Montreal, creating a novel that’s not hitting its readers over the head with symbolism and parallels, but creating an organic and realized narrative that also remembers to run on its own steam?

Why, by structuring the novel as a double album, of course, this structure an homage to one of the story’s main characters, Serge Giglio, who headed a Quebec nationalism progressive rock band in the 1970s that never exploded like it might have because he refused to compromise and sing in English. So that the book becomes a sort of novel in pieces, but the pieces are drawn together compellingly and satisfyingly, moving between decades and characters and continents to culminate in what feels like an epic.

Rani grows up in 1970s’ Montreal, the daughter of immigrants, and finds herself drawn to Sensibilité, Serge Giglio’s band, to the point of obsession, though her relationship to its lyrics are complicated as a brown woman in Quebec who was barred from French schooling because she wasn’t baptized. When she meets Serge’s young daughter Mélanie, adopted from Vietnam, she’s drawn to the child because of her affinity for her father’s music, but perhaps it’s more than that. And when she connects with Mélanie again almost two decades later, this is affirmed for her, and she begins to wonder for the first time about her own parents’ experiences in Partition-era India and if she might be any more connected with these stories than she is the ideas Serge sings about in his songs.

While Rani serves as the main point of convergence between the various solitudes explored by Anand in her novel, the other characters—Sunil and Hima, her parents; Serge; his English wife Jane; Mélanie herself—are just as central to the text, the narrative portraying their various points of view and how these unfold over decades and between nations and continents, the connections between them (and also disruptions) serving to complicate notions of solidarity and independence and colonialism in a way that’s illuminating and fascinating, enlivening and unravelling ideas that might sound neat and tidy as political slogans but are more difficult to contend with in actual fact.

June 20, 2022

Susanna Hall: Her Book, by Jennifer Falkner

“July 11th, 1643: It is the summer of her 61st year. A year of turmoil up and down the country. The King has abandoned his seat in London and his army charges about fighting his own people. A year of exorbitant taxes. Poor harvests. Neighbours turning against each other. A year in which Susanna wonders how many years are left to her.”

For fans of Hamnet, by Maggie O’Farrell, I recommend Jennifer Falkner’s Susanna Hall: Her Book, a gorgeous and haunting novella inspired by another Shakespeare woman, this time the poet’s eldest daughter, Susanna. Physician’s widow and respected healer, the tensions of England’s civil war have arrived to roost within her home.

With historical fiction that reads as timeless and achingly relevant, Falkner manages to have 150 pages contain the broadest emotional spectrum, and lets just three days tell the story of one woman’s remarkable lifetime.

I loved this book, out now from Theresa Kishkan and Anik See’s Fish Gotta Swim Editions, indeed a pleasure to read and to hold. If you’re intrigued, check out the posts on Falkner’s Pinterest page!

June 16, 2022

No Second Chances: Women and Political Power in Canada, by Kate Graham

“Democracy is, I would say, so important in our collective lives, in our states, that you never question it even if goes against what you believe.” —Pauline Marois

If politics is messy, actually governing is even worse, the challenge arriving with realities and demands that most of us observing from the sidelines barely understand. And being a woman in government, as Kate Graham shows in her book No Second Chances, based on her 2020 podcast of the same name, makes the challenge even harder. As noted by Kim Campbell, Canada’s first and only female Prime Minister, “When you are not prototypical—when you are not like the others who have the done the job—it becomes very difficult for people to overcome their visceral sense that something is not quite right, so you never get the benefit for the doubt…”

In Canada—even where there was a moment a few years back where half of our First Ministers were women and it seemed like something like equality had finally been attained—not a single female First Ministers has never been re-elected.

Throughout the interviews in this book, Graham teases out a handful of reasons why this might be the case, and none of are that women are necessarily inferior at political leadership. The interviews take place with women across a wide range of the political spectrum too, whose experiences turn out to have far more in common than one might suppose.

These interviews are as fascinating and insightful as they are infuriating, which is sure saying something! Confirming a lot of what I’d already supposed, about how women are often given opportunities for leadership when everything’s about to collapse, about how they don’t receive the same benefit of the doubt as their male colleagues (and even from their male colleagues), about how the media still doesn’t know how to talk about women in leadership in constructive ways, and more.

The most surprising takeaway though, though it’s not explicit in the text, is that so many of us are also responsible for the problem. I think about how I know so many women in these interviews from hearing friends in other provinces express their grievances—Alison Redford, Kathy Dunderdale, Christy Clark, and even Rachel Notley (whose leadership in Alberta would bring with it compromise). I thought about the vitriol directed toward Kathleen Wynne in Ontario, like nothing I’ve ever witnessed before. There is just something visceral in the way these figures are disliked that doesn’t happen with men in similar situations. And while one exception to the rule might be Jason Kenney, I feel like this proves the point—he’s about seventeen times as terrible as any of the women I’ve just mentioned, and only now have things gone wrong for him.

I’m tired of blaming the problems of politics ONLY on the other guys, an idea I wrote about last fall, because this suggests that there’s nothing I can do personally to ameliorate the situation, and also because it just isn’t true. Across the board, I think we tend to have unrealistic expectations for what our governments can deliver—and parties/candidates don’t help the matter by drumming up simple messaging in campaign-mode belying the true complexity of solutions our current challenges require. The truth of the matter is that all this is hard, compromise is necessary, and that we all need each other—and faith in each other—for democracy to function.

June 14, 2022

Gleanings

- To bring a child into this world has always been an act of hope. The past was its own parade of horrors. The best estimates we have suggest that across most of human history, 27 percent of infants didn’t survive their first year and 47 percent of people died before puberty. And life was hard, even if you were lucky enough to live it.

- When I write about Woolf myself, I feel the same anxieties Queyras expresses in their book, about taking Woolf as a subject and about adding to what’s already been written about her. It’s hard not to feel both inadequate and superfluous.

- Some times there are moments when everything hard falls away. You forget you’re tired because the sunlight falls just so across the table you’re sitting at

- the summer pushes me right out of my wrappings and out into the light. I hate it. I love it. (mostly I love it when its over, and I look back on what i have survived.)

- We may think we make ‘airy-fairy’ wishes, then forget all about them. But they remain deep inside us, percolating, finding ways to emerge and become real.

- As someone who has side-gigged at bookstores and libraries most of my adult life, I’ve always been fascinated by how we find books and authors, how sometimes the right book will find us at the right time.

- “I love for people to know more about books and reading, especially Black people,” Nurse says. “I want them to experience the power of their own imaginations. We are not entirely reliant on this crazy white world; we can go places in our heads and make things happen.”

June 8, 2022

Night in the World, by Sharon English

“There’s so much to learn—and to unlearn. It’s urgent yet can’t be rushed. The world stands on the edge of losses so radical no one can fathom the consequences, while possibilities for reconnection and renewal wait to be discovered in the dark.”

I don’t want to read your climate change fiction, that novel you wrote about children afloat on a raft as the world is overwhelmed by sea. I don’t want to read about your desolate prairie wasteland, about drought, about despair, about the impossibility of a habitable future. And not because I don’t think that the climate crisis is pressing and real, but because I know that it is, and I know your post-apocalyptic fiction isn’t going to do anything to ameliorate that reality, or lessen my anxiety. Perhaps also because I don’t think I believe in apocalypse at all, but instead that in the midst of disaster, ordinary life goes on—babies are born, flowers grow, people do their best, and help one another. Reality is not so stark. The story, as always, is complicated.

And this is the kind of story that Sharon English—celebrated author of two acclaimed short story collections—has decided to tell in her debut novel Night in the World, a novel whose disaster setting feels a lot like now, and why shouldn’t it? Freak storms knock out power grids, water levels are rising, toxins are mucking up the waterways, and anyone who speaks out against the pervasiveness of, say, fluoride in drinking water is just dismissed as loony toons. Entire species are being eradicated as their habitats are destroyed in pursuit of profit and development, few people pushing back against the status quo, underlining its unsustainability.

Night in the World is the story of a pair of brothers, one a successful restaurant-owner who finds his middle years are drained of meaning, the other a former environmental journalist who’s thrown it all away for a job that seems less futile, helping to run a gym in East Toronto. And the third character at the centre this story is a late blooming grad student who lives in Peterborough, and is studying moth species around the shores of Rice Lake, and elsewhere, trying to find a way to do her research without damaging the fragile creatures she’s pursuing. Is a little harm excusable if it’s the name of a greater cause?

The novel traces the lines of Toronto’s waterways, the creeks and rivers underlying the modern city, stories that refuse to stay buried, as well as the ever-shifting shores of the Toronto Islands, formerly a peninsula until a storm cut them off from the city more than a 150 years ago, and Rice Lake, an important agricultural spot for Indigenous people…until the radical disruption of the Trent Severn Waterway, all of this conjuring moth’s more colourful cousins, and what can happen when one of them flaps its wings. The infinite ways in which every little thing is connected.

“This novel was over a decade in the making,” English writes in her acknowledgements, and I will admit that sometimes it reads as such, the story big and sprawling with many disparate parts that sometimes fit together awkwardly. In terms of plot, there’s nothing taut, and I wouldn’t say that it’s a great novel, but instead that it’s a very good and wholly worthwhile book, a book packed beautiful sentences and details so fascinating I kept reading facts aloud (the part about the cicadas!), bursting with research, and ideas, and questions, poetry and philosophy.

June 6, 2022

This Time Tomorrow, by Emma Straub

Is novelist Emma Straub overhyped, I wondered, as I pre-ordered her latest novel This Time Tomorrow? And if indeed this is the case, am I part of the problem, pre-ordering her latest novel when the truth is her previous book didn’t really blow me away? I was a big fan of The Vacationers many years ago, and I’ve enjoyed her releases well enough since, but I was kind of resigned to This Time Tomorrow being something of a let-down, as are too many buzzed-about new releases. But oh, I’m so glad I didn’t miss this one, because it’s one of the best books I’ve read so far this year.

Though it matters, I think, that I’m something of a time travel fiend. Tom’s Midnight Garden, Charlotte Sometimes, and A Handful of Time are some of my favourite novels from childhood, and Straub’s references to movies like Back to the Future and Peggy Sue Got Married were absolutely delectable to encounter. It matters too that this is a time travel novel wholly self-aware of its genre and its place in the canon. In this case, it’s personal—protagonist Alice Stern’s father is author of the iconic novel Time Brothers, a time travel cult classic.

When the novel begins, Alice’s father Leonard is dying, silent and still in his hospital bed. Alice herself is on the eve of her 40th birthday, still living in the New York City she grew up in, still working in the same Manhattan private school she’d been a student at. She likes her life well enough, but her father’s condition and her milestone birthday are inspiring her to take stock and wonder how they got there and what else could have been

The novel features amazing Russian Doll vibes—after visiting a bar called Matryoshka, Alice wakes up in her teenage body, and proceeds to relive her birthday again and again, each time returning to the present to find her life very different due to choices she’d made. And while being trapped in a time loop might seem like a problem, to Alice it’s an opportunity to spend time with the father whose humanness and availability she’d always taken for granted when she was young. As one does.

What I love about this book is that almost none of the story was taken up by Alice trying to hide her situation from those around her. No, like any reasonable human, Alice takes advantage of her best friend’s intelligence and her father’s expertise in the area to loop them in and ask for help, so that the story becomes one about bigger questions, about the connections between generations, about the choices we make, and why they matter (or don’t!), plus a wonderful exercise in ’90s nostalgia.

It was smart, warm, and so delightful.

June 1, 2022

This is How We Love, by Lisa Moore

You wouldn’t say that Lisa Moore’s new novel This is How We Love is unputdownable, but I honestly think that’s a lot to ask of a novel . It took me almost a whole week to read it, because it’s kind of long, and I had a lot going on, so I kept picking it up and setting it down again, and the narrative style was doing something similar. The novel far less taut than you’d think for a plot with the stakes of a critical stab wound, an ICU, and a once-in-a-century snowstorm that brings St. John’s to a halt before it buries it under. But taut plots aren’t really what Lisa Moore is all about anyway. Or at least I don’t think so—nine years ago I read the first half of her novel Caught, which of all of them might be a contender for taut, while in labour in the bathtub, and afterwards I had strong aversion to ever reading the rest of it. From the rest of her novels, however, I know she’s all about the sentence, one word after another and how they all flow like waves, but they’re pushing us out to sea instead of drawing us to shore the way that actual waves do. Until we’re stranded on an inflatable raft like Trinity Brophy was before the authorities removed her from her mother’s care and delivered her to live with Mary Mahoney, the foster mother who raised her across the street from Jules’ house.

I wouldn’t say that Lisa Moore’s new novel This is How We Love is unputdownable, but I can say that over a week since I finished reading, I can’t get the story out of my head. About Jules, whose son Xavier is stabbed while she’s on vacation in Mexico and there’s only one seat on the first flight back so she takes it, arriving just as St. John’s is shut down entirely. So she’s there to deal with the peril of Xavier’s condition, and then all the snow, which falls and falls so the doors are blocked, except the back door, but it’s only because there’s been so much snow that the deck fell off the house.

The story moves between Jules’ point of view—her perspective on what’s happening to her son and reflections back in time too, to her mother and mother in law, to the early days of her marriage, her experiences as a mother, a stepmother. This is a book about care, about who we care for and who we don’t, and how some people belong to us, and other people don’t, and what happens to everyone when those people fall through the cracks—and those of Xavier himself, and Trinity Brophy, his childhood playmate who is somehow connected to what happened to him. Moore weaving so many different narrative threads together to begin to answer the question that’s mostly preoccupying Jules, which is WHY? Why did somebody hurt her son? Why would anybody want to do something like that?

Spanning decades and families, This is How We Love underlines the infinite ways in which lives are all connected. Part novel, part guidebook to the wondrous challenges of being a being.

May 19, 2022

Mercy Street, by Jennifer Haigh

I spent a few days last week utterly gripped by Jennifer Haigh’s novel Mercy Street, which I picked up after reading a New York Times review and after someone else had mentioned it to me as being a novel about abortion. A bit like Jessica Winter’s The Fourth Child, in that it’s a novel about abortion as much as it’s a novel about anything, a story propelled by its own internal engine, which is just what a novel should be, I think.

This one beginning at a Boston abortion clinic during a brutal winter in recent times where a woman called Claudia counsels those arriving for various reasons—unwanted pregnancies, birth control, other health concerns. Haigh’s novel underlining the huge range of situations which bring a person to an abortion clinic, to have an abortion at all, some of them brutal and devastating, desperate and tragic, and others much more mundane. What does it mean for the addict who sits before Claudia, for example, to have to continue with her pregnancy? (Abortion in Massachusetts is legal only until the 24th week of pregnancy.)

Claudia enters the novel with her own story, of course—her mother was a teen-mom, she grew up in a poverty, a background she overcame for success writing for women’s magazines and a brief first marriage. She’s still friends with her ex, but her job in journalism is far behind her, Claudia finding more meaning counselling women who come to the Mercy Street Clinic, but the job is a lot, and there’s a weight on her that’s far heavier than the keys she possesses to her late mother’s single-wide trailer in Maine, a property Claudia has put off doing anything about for a very long time.

Claudia finds solace in smoking cannabis, and in the company of Timmy, her dealer, who’s trying to think of a different way to provide for himself and support his teenaged son who lives in Florida, and the narrative moves from Claudia to him, and then to Anthony, one of Timmy’s clients, who’s been on disability for years, still lives with his mother, attends mass daily at a local church, and takes care of local parishes’ websites. His online dealings putting him in touch with an antiabortion crusader called Vince who, over the past two decades, has been radicalized by the white supremacist undertones (and lately overtones) of talk radio, and is setting out a plan that could have devastating consequences.

This is a novel about a butterfly who flaps its wings, about fate, and agency, and how one thing, for better or for worse, leads to another. Gripping, galvanizing, sympathetic, and infuriating, I enjoyed Mercy Street so much.