June 15, 2023

Some There Are Fearless, by Becca Babcock

I had such a visceral response and connection to Becca Babcock’s Some There Are Fearless, a novel that begins with the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 and concludes on January 8, 2020, as a Ukrainian plane is shot down in Iran, a day that lives as a portal in my own mind as “this very weird time,” which is fitting (and eerie, and interesting) for a novel that is all about fear, and anxiety, and our notions of controlling and mitigating risk.

Jess grows up in Cold Lake, AB, in the shadow of the Cold War, living just outside a military base. The Chernobyl meltdown absorbs her attention, and this preoccupation, coupled with her academic aptitude and her single mother’s push toward achievement, leads her toward training as an engineer and then a career with Maritime Energy in Nova Scotia retrofitting coal plants, with aspirations to one day work in the nuclear field and prevent disasters like Chernobyl’s from ever happening.

There are other cold wars in Jess’s life—her father has long been estranged from their family, her difficult mother’s fraught relationship with Jess’s brother fills their home with tension, and Jess’s own connection with her mother doesn’t get any easy once her brother leaves to go get a job in the oil fields, putting even more pressure on Jess to be the one who succeeds. She finds solace in the company of Adam, a fellow engineering student, however, and they begin to build a life together, although it’s not always easy for Jess to connect, but they establish compatibility and eventually they have a child, and I love the way that Babcock subverts expectations about how the emotionally distant Jess might be rocked by motherhood (and Jess subverts her own expectations too)—”How could love be spontaneously generated? How could a body feel so much, be so enraptured with another creature who, moments before, had only existed as a kernel and a germ, and who now, just now, breathed in the world, became the most precious thing in that entire world for her two parents? How?”

In a world with Three Mile Islands, and Fukushima Daiichi, it’s hard to relax—though Jess explains that the nearby Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant managed to avoid the same catastrophe that its sister plant was unable to prevent after the devastating 2011 Earthquake. And the illusion that she is eventually freed from, the trajectory of her story—which artfully braids together different timelines—is her gradual understanding that she’s not actually responsible for keeping the world safe, and that she can’t actually keep ill fortune from arriving at her doorstep, as her relationship with Adam falls apart, and her daughter undergoes testing for an “uncertain shadow” on her MRI. Jess can’t help but wonder if it was caused by the guided tour she’d taken to the Chernobyl zone nine months before her daughter was born, a risk exposure that seemed minimal and worth it at the time, but how do you ever know?

As someone with a Cold War fascination who has spent the last 18 months learning to live well again after experiencing debilitating anxiety, Some There Are Fearless really resonated with my own preoccupations, with my own challenges of making my way, as a person and as a mother, through our own particular age of anxiety. Blending beautiful writing with history and science, Babcock has created a rich and satisfying depiction of what it is to live in a world that is rarely steady.

June 12, 2023

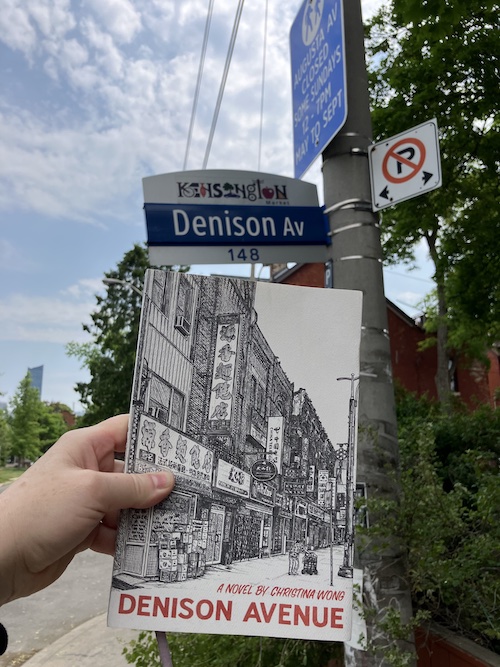

Denison Avenue, by Christina Wong and Daniel Innes

The nature of cities, of course, is that cities change (I wrote about this in my 2017 essay about Ann-Marie MacDonald’s ADULT ONSET, a book that maps on to this one in surprising and interesting ways), but anyone who loves that city or calls it home is going to struggle with that, or maybe that’s even just the baked-in nostalgia that comes from being alive. I’m well accustomed to stories and images of “Old Toronto,” the kinds of photos that get shared in Facebook groups with names like “Long-Gone Toronto,” the kinds of images that Kamal Al-Solaylee writes about in his 2014 essay “What You Don’t See When You Look Back,” about the whiteness of these vintage scenes: “The pictures depict a world where only white people roamed the streets or were allowed into the frame. I can’t help but conclude that the friends who post them would have preferred it if Toronto had stayed that way: small town, white, exclusive and free from people who look like me.”

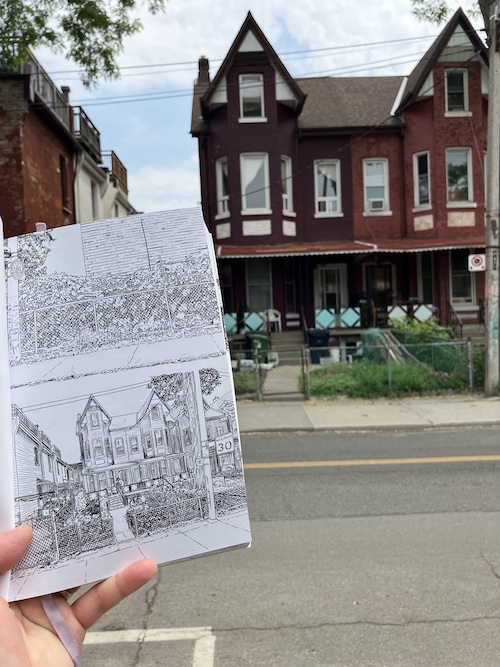

But in their new book, DENISON AVENUE, Christina Wong and Daniel Innes are doing something different, and in more ways than one. First, the book itself, which is double sided, one side telling the story gorgeously in Wong’s prose and poetry fragments, and the other with panels showing Innes’s drawings of Toronto “now and then,” now being about ten years ago—when Honest Eds was sold and the Kromer Radio property on Bathurst was going to be developed into a WalMart—and then during the years before it with a thriving Chinatown and Kensington Market, before these areas had become ripe for development and working class people could live a decent life downtown.

Within Innes’s contemporary drawings, a figure appears pushing a cart along the sidewalk, picking up cans and bottles along the way, a figure I didn’t even notice the first time I flipped through the book, which is the point of the book, about what remains invisible, and who gets to be seen, and heard.

The woman in the drawings is Wong Cho Sum who immigrated to Canada in the 1960s and lived in a house with her husband on Denison Avenue until his death (when car sped past the streetcar doors on Dundas Street). Together they had built a steady and comfortable life with strong community ties, but in the wake of her husband’s death and the city’s changes (which are not bemoaned just because it’s change, but because these are changes that make life more difficult for Toronto’s poor and marginalized people, something Cho Sum has seen before as the city’s previous Chinatown was forced to move west when the area was redeveloped as New City Hall) she finds herself unmoored from the world around her.

To fill her days (or perhaps I mean her evenings and early mornings!) she begins collecting cans and bottles around local neighbourhoods, developing a route up and down streets that are familiar to me.

What I loved about this book was how it told the story of a changing Toronto from the perspective of a person of colour, a person who speaks very little English (in the book, Wong writes her dialogue in the Toisan dialect), which is a perspective I’ve never heard before. And similarly, though elderly women collecting bottles and cans are as ubiquitous in my neighbourhood as they are in Innes’s drawings, I’ve spent very little time considering these women’s perspectives, what brought them here, why they’re doing this—for Cho Sum, it’s to earn a bit of money, and give shape to her days, and for exercise. In so many ways, for me, Denison Avenue was absolutely a revelation.

And it was also just a tremendously moving story of strength and resilience, of love and courage, and friendship and community. (There is a swimming scene!! I just adored it.)

The nature of cities, of course, is that cities change, but in Denison Avenue, Wong and Innes manage to capture a unique view of the city as it was for just a moment, all the while making their readers consider what the city might become if we think about what it’s true heart is, which is to say the people who live here.

June 9, 2023

Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden, by Camille T. Dungy

With the essay collection Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys Into Race, Motherhood, and History, Camille T. Dungy became one of my must-read authors, although I might have read her follow-up Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden anyway on the basis of that gorgeous cover (and oh my goodness, wait until you see the inside covers!!). Soil is a book about metaphors, but also about the thing itself and, to begin with, that this is the garden that Dungy designs and brings to life in the yard of her suburban home in Fort Collins, Colorado, a place where the propagation of native plants and a wild-looking garden is in defiance of home owner association standards about such thing as grass lengths, and Dungy and her family are part of the reason that culture begins to change.

This is a memoir about the labour (and setbacks) in cultivating diversity in our gardens, and beyond them. It’s also a story of receiving a Guggenheim grant to write a book whose progress is stopped up by the Covid-19 Pandemic and a ten-year-old child whose home schooling requires supervision. It’s about being a Black person and a Black mother in America in the wake of the 2016 election, whose fallout in a continuation of centuries of struggle and oppression, and what it feels like to be confronted by deaths of other Black people, those names like beads on a string over the past decade and more—Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd. Like a rosary.

She quotes her father’s response to a (white) reader’s question about how Dungy could consider herself an environmental writer when she spends so much time writing about African-American history. Her father (Dr. Claibourne Dungy) answers, “For us, there is no separation between the environment and social justice.” It’s not one thing or another, but instead everything connection, our environment home to the world we choose to build here, and also to the natural elements over which we have no domain (or at least cannot even imagine we do) and here Dungy writes of wildfires across the state of Colorado during that already miserable plague year, where neither indoor air nor outdoor was safe to breathe in the company of others, and disaster seemed perpetually just shy of the doorstep.

This is a book rich with love, wisdom, and humour, a book about neighbours, about community, about marriage and love, about trying to save truckloads of soil from blowing away in a windstorm. It’s about climate change, and weather, and history, and botany, and place, and travel and belonging, and longing, and grieving, and persisting. It’s about faith.

“Faith is the belief in things not seen. Or it is the hope that what has not yet materialized might, someday, manifest… One of the hallmarks of faith is to believe in a promise and—though the promise has yet to come to pass, and may never in my lifetime be fully fulfilled—to find a way to carry on. To discover and honour what HAS come to fruition.

I dig up a lot of awful history when I kneel in my garden, But, my god, a lot of beauty grows out of the soil as well.”

June 6, 2023

The Opportunist, by Elyse Friedman

There are all the book whose blurbs promise you they’re unputdownable, and then they were the books that are just impossible to put down, and Elyse Friedman’s The Opportunist is both. It’s the story of a woman estranged from her wealthy family whose brothers only get in touch because they want her to help get their elderly father’s fiancee—his twenty-seven-year-old nurse—out of the picture and preserve their inheritance. A single mom of a disabled daughter who ekes out a living working at a domestic violence shelter, Alana agrees to head back into the family fold because she’s promised enough money to buy her daughter an accessible mini-van. When she arrives at the family estate, however, her father’s gold-digger girlfriend turns out to be nothing like what she’d been led to expect, and more savvy than anybody is giving her credit for. Loyalties, much like the ground beneath these characters’ feet, are ever shifting, and just when the reader thinks they’ve got a handle on the situation, the next chapter reveals another unexpected twist, not to mention a whole new level of depravity. I’ve never seen Succession, but I think this excellent novel might fill the void its finale has left in the world of its fans. Taut and compelling, not to mention VERY FUNNY (the line about the orangutan!), The Opportunist is a glorious fuck-you to the patriarchy, and ends on a note as surprising as it’s glorious. Put this on your summer reading list right now.

May 29, 2023

Books Round-Up

Some books I’ve been reading lately that you deserve to know about!

*

You can never have too much of a good thing, especially if the good thing in question is an extension of @alikbryan’s smart and hilarious debut novel ROOST. Its follow-up, COQ, is set a decade later as Claudia’s father has just remarried , now it’s her brother’s turn to have a marriage fall apart, Claudia’s ex husband is displaying peculiar symptoms of wanting to get back together, all of this against the backdrop of an epic family trip to Paris to remember Claudia’s late mother. COQ is a romp, deeply felt, a delight.

*

In her new memoir UNEARTHING, Kyo Maclear’s achinging personal experience—after the death of her father and a chance encounter with a DNA test, she discovers that her father was not her biological father after all, and any attempts to understand the true story of her origins are obscured by her complicated mother whose diagnosis of dementia only makes clarity harder to find; or does it?—turns out not only to be a fascinating mystery to unravel, but also a meditation on the possibilities of story and family itself, about what it means to relate to or be related to some people and not others. It’s also a story of seasons, and gardens, what can be found in the fog, and the importance of leaving room in your list for strange and unexpected things to happen. It’s so good.

*

I loved this book, a novel that was everything it’s beautiful cover had led me to suppose it might be. A novel that author Margie Taylor wrote with a specific audience in mind, women over sixty who are imagining their lives are set, children are grown, marriage established, when along comes a series of new seismic shifts that change everything. For the eponymous Rose, it all begins with her husband’s abrupt announcement that he’s retired from university teaching, and then her daughter moves home, and then Rose invites a charismatic young man into the family fold who’s nothing like what she thought he was, and suddenly Rose Addams’ comfortable life is turned upside down. A novel about family and friendship and the limits of what a wife and mother can control, ROSE ADDAMS was smart and funny, a delight to encounter, and reminiscent of Carol Shields’ fiction.

*

This Bird Has Flown, by Susanna Hoffs

Susanna Hoffs wrote a novel…and I love it? Which shouldn’t be so surprising, because Susanna Hoffs also wrote “Eternal Frame,” which is a work of art that’s moved me more times than most works of art I can think of. But you know what? I’ve been disappointed by fiction by ’80s superstars before, so I went into this novel carefully, cautiously. The story of a one-hit wonder 33 year-old-old singer whose failure to launch is getting her down…when she is seated next to an impossibly attractive Oxford English Professor on a flight to London, and sparks fly (and then some!). If you’ve got a thing (and I sure do!) for fiction with a lot of swearing and nearly as much masturbation, then this book is for you. It was funny, fresh, and surprising, managing to blend rom-com and Gothic tropes (JANE EYRE! REBECCA!) in bizarre and splendid ways. What smart, smart fun.

*

At first I wasn’t really sure I NEEDED to read an updated version of THE PURSUIT OF LOVE, by Nancy Mitford, but it turns out that India Knight’s modern day spin is very funny, perfectly delightful. As good as that cover.

*

Song of the Sparrow, by Tara MacLean

I remember Tara Maclean’s “If I Fall” playing on the radio when I was 20 and full of angst, and I remember writing the lyric “It looks like a good place here/ so I think I’ll stay for a while” in the margins of my Norton Anthology while thinking about boys who I wished would love me. (And in my mind, that song on the radio would always be followed by “Love Song,” by Sky. Oh, how music is a time machine.)

I first heard about her new memoir, SONG OF THE SPARROW, from my friend @marissastapley who was blown away by MacLean’s story of her unconventional childhood on Prince Edward Island, born to practising Wiccans who’d become Evangelical Christians who filled her world with meaning and magic and music, but who also left her vulnerable to abuse and neglect. A devastating low point of her peripatetic childhood was when MacLean and her siblings were nearly lost in a house fire that made national headlines.

In a story that recalls the essays in Sarah Polley’s acclaimed memoir RUN TOWARD THE DANGER, Tara MacLean bravely faces down the darkest corners of her history and shows how trauma doesn’t have to be the end of a story. With exceptional grace, generosity, wisdom and faith in her own power, MacLean shows the possibilities of going beyond mere survival and creating a rich and vibrant life of one’s own.

Her stories in 1990s’ music success are also really wonderful to read, filled with familiar names, and perhaps the best kind of namedropping, because each one includes an anecdote or detail about what that person taught MacLean and just how generous or exceptional they are. (Special shout out to Tom Cochrane and his wife Kathy who invited MacLean to give birth in their house!).

A beautiful memoir about what it means to stay steady on ever-shifting ground and even rise above it to fly.

May 25, 2023

Snow Road Station, by Elizabeth Hay

An essential part of my writing process is getting to the point where I know my characters well enough that that every bit of dialogue becomes essential to my story, no single line that’s incidental or something that anybody else would say to any other person on the planet. This is especially true with fictional people who’ve known each other for decades: there is no small talk, every sentence loaded with meaning, with freight. In Elizabeth Hay’s new novel SNOW ROAD STATION this can be disorienting for a reader, like walking into a room in the middle of a conversation, but this is also what fiction should be, I think.

I really liked this book, though its effect was more subtle than powerful, which is fine because it’s a slim read and I have time to pay attention.

I really liked this book, a story of late middle age and long friendship (“Theirs was a childhood friendship that had lasted, enduring long spells when it existed out of sight, but then there it was again, like strawberries in season.”) but it was not until its final paragraph, which hits with such a force, nothing subtle about it, that I began to really understand the project, what a complicated fascinating book this quiet story really is.

May 17, 2023

Our Wives Under the Sea, by Julia Armfield

I am infinitely grateful to whoever it was who inspired me to put this on hold at the library. OUR WIVES UNDER THE SEA, by Julia Armfield, was incredible, blending literary elements with horror to create a spellbinding tale of love and loss. The point of view moves between Miri and her wife, Leah, a marine biologist whose routine research trip goes wrong when their submarine sinks and is lost to contact. Six months later, Leah comes home again, but something is very wrong and Miri is unable to reach her, or get answers about what happened in the deep, a story Leah tells piece by piece in her part of the narrative. This is a novel infatuated with the wonders of the world, oceans and love among them. Creepy and compelling at one, a strange inversion of THE SHAPE OF WATER, and definitely one for readers who loved Melissa Barbeau’s THE LUMINOUS SEA, or anyone into JAWS. What a story!

May 15, 2023

Places Like These, by Lauren Carter

“I never though something like that would happen in a place like this,” is the thing people always say in local newscasts in the aftermath of tragedy, as though there were actually places in the world that immune to life itself, to its terrible, tragic unfairness, and inexplicability (and isn’t this part of the same reason people travel, to escape all that?) but, as Lauren Carter shows in her fantastic new collection Places Like This, life happens everywhere, on rural highways, far flung suburbs, northern towns, and abandoned homes in the middle of nowhere. In the New York state spiritualist community famous for its mediums, a stuccoed church in Argentina, in the shadows of San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighbourhood (“Carol did not tell her how she’d envisioned a slab of raw beef, glaring a wet red before purpling like an aged bruise. The expensive cut, one her mother would have rarely purchased at the downtown butcher shop with the creaking wood floor, the dusty cans of corn niblets and cherry pie filling.” ).

These are stories of sadness and longing, of wanting but not getting, but this—of course—is also life itself, and the collection is less bleak than it sounds, because these are stories of characters building a home and a finding a world within its realities, of finding love, spots of light, connection and meaning. Even in “places like these,” rich stories are possible, such as that of the couple whose dog is saved as the narrator’s struggling stepbrother begins to slip away; a widow keeps seeing her late husband; a woman glimpses the depths of her partner’s sadness when she goes home to meet his family; the couple together but emotionally worlds apart as they grieve a pregnancy loss, which is also the loss of so much love and so many dreams. I especially loved the three final stories in the collection, linked narratives about a group of women who’ve been friends since high school whose own ties are fraught, complicated, and irrevocable.

These are tough stories, rugged and hard, but there are also gorgeous moments of connection, of illumination—I keep thinking of a description of a drink in a character’s hand, “a bowl of light.” There are stories that shine.

May 2, 2023

The Light of Eternal Spring, by Angel Di Zhang

“My mother died of a broken heart, or so the letter said.”

And this is the spectacular opening line of Angel Di Zhang’s dazzlingly dreamy debut novel, The Light of Eternal Spring, a story of love and loss, a story of finding and belonging, about seeing and knowing, all the gaps between what we remember and what really happened, and the curious nature of space and time. How did we get from there to here?—a question that preoccupies Di Zhang’s protagonist, Aimee (pronounced Eye-Me), particularly after her mother dies and she travels with her American husband back to her hometown in China, the rural village of Eternal Spring, where she hasn’t been for so many years. It’s also the question the narrative sets out to answer.

Aimee, a photographer, is known as Amy in her new life in New York City, where she is now so established that she thinks in English, and her photos appear in ads on the subway, and she thinks her thoughts first in English instead of her native Mandarin. Though it’s Manchu that’s Aimee’s mother tongue—literally, her mother’s first language—and she’s forgotten it to the point when her sister’s letter arrives with news of her mother’s death, she has to have it translated by a woman in Manhattan’s Chinatown running a vegetable stall.

It’s 1999 and communication is not as instantaneous as it is today. When Aimee and her husband David set out for Eternal Spring in the hope of making it back in time for her mother’s funeral, she has no idea what to expect, and her family don’t even know to expect her. What she’ll find is a place and people who are radically different than they were when she last saw then, by virtue of the nature of memory, but also because the previous decade has been a time to radical change in the village, which has become busy and bustling, not a village at all. Because nothing ever stays fixed, both in life, and in our memories, and such understanding is a challenge for Aimee, whose photos aim to capture time, to hold it still.

How to grapple with the mutability of reality? And even more important, how to resolve her relationship with her mother now that her mother is gone? The last time mother and daughter were together led to a spectacular flame-out and they haven’t spoken since. Will there be any chance for Aimee to to reconcile with her mother’s memory? And what about reconciling the space between Aimee and Amy, between the place where she comes from and where she lives now, and possibility of belonging to both places, a kind of double exposure, not a photographic error but instead an accurate image of her psychic reality?

I loved this book, its freshness and sense of play, its curious placement outside of time, just beyond the limits of realism, about the all the possibilities of impossible things.

April 17, 2023

Birnam Wood, by Eleanor Catton

True confession time: I’ve never read Eleanor Catton’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel The Luminaries, and I likely never will. Reportedly, it’s very lengthy, set a long time ago, and all about a man staking his claim in a gold rush (yawn), and no doubt it’s extraordinary and brilliant, but each of these makes for three counts on my NOPE NOPE NOPE list, and there are so many other books in the world.

My interest in Catton’s latest Birnam Wood, however, was piqued by critic Lauren Leblanc’s enthusiasm for the project, which was also the reason I went to see Catton at the Toronto Public Library’s Bluma Salon event in early March, which was really fantastic, and I bought the book there. She kept talking about plot, and about how “character is action; we are what we do,” and I was intrigued, though I’ve got to say that even though this novel clocks in at only just over 400 pages, I picked it up thinking of a doorstop, and what have I gotten myself into? There was not a lot of white space. Will I be reading this novel for the next 900 years?

But reader, I sped through it in two days. This book! This book! Speaking of plot… Though it didn’t take off immediately. I was interested in the story and surprised to find that it was so much more intimate and immediate than I was expecting, deeply embedded in the experiences of characters ranging from the leader of the gardening collective, her loyal sidekick, a renegade citizen journalist, a pest-control mogul who has recently received a knighthood, his wife, and a reclusive American billionaire seeking refuge in middle of nowhere New Zealand for reasons that aren’t bound to be honourable. I thought this would be a more sprawling book, individual people at a distance, more a book in general than this one, which is so exactly, specific. Even though the paragraph-long sentences were hard to parse at first, so many clauses, and semi-colons. Like making one’s way through the weeds and the bramble, and then suddenly there I was at the heart of things and the novel was unputdownable.

“She was still looking for a villain. She was still trying, desperately—and uselessly—to find somebody more monstrous and despicable than her.”

Who is the villain of this story? Who is the hero? Such murky distinctions (if any are to be made) are what make Birnam Wood such a fascinating puzzle of a story. I loved it.