March 9, 2023

Ordinary

A year ago, my mental health was terrible—a sentence that will be evergreen for me until the end of June—but early March was a particular low point, my anxiety ramped up again and me still so far from understanding how it played such a dominant role in my mindset and how much of my worldview was informed by a catastrophic thinking I’d just accepted as normal. I remember one of our first dinners out in a restaurant and not being able to enjoy it at all, because I spent the entire meal quite sure that we were all going to die quite shortly, and it was almost a little bit fascinating to look around me and see how everybody else was just taking it on the chin.

It was not a good time. And yet, there was sweetness. We were moving through March and the first one in three years that didn’t come with absolute dread. When my children brought their indoor shoes home for March Break, it wasn’t because I wasn’t sure they wouldn’t see the inside of a school again until September. We were eagerly anticipating our long awaiting trip to England, but Covid was also still surging, the idea of travelling was stressing me out, and I wasn’t sure that every March until the end of time would not take the shape of a spiral toward doom. I was incredibly moved last year to have our first ordinary March Break in such a long time, and so have my kids return to class as normal afterwards—but it also still felt precarious. Those convoy people had broken my soul. It felt so good for things to finally be okay again, but I still felt so far from okay.

And then this morning, 365 days from then. Another day of sunshine and blue skies, and there is this way the sunbeams appear in my kitchen around 8:30 in the morning from the southeast, making their way around my neighbour’s house and onto the counter, my cupboards, so golden, and my children were happy. We were putting lunches in their backpacks. They’ve stopped wearing masks to school. Iris had a school trip to the art gallery yesterday. Harriet’s school had an open house today so we could visit and see the zoo exhibits she and her classmates had built. Yesterday I had a meeting with my publishing team to hatch plans for my upcoming book. I spent the afternoon in a cafe finishing edits and eavesdropping on idiots, and then attended an event for International Women’s Day with wine and cheese, the first event held in the PRH office since March 4, 2020, back when everyone was wiping down surfaces out of an abundance of caution.

And this. The sun. This week. Today. In the deepest pit of pandemic despair, this ordinariness was everything I longed for, everything I missed to my very marrow. Backpacks, and laughter, and learning, and growing, and walking the route to school that I’ve been walking now for a decade. Things to look forward to. Moments to steep in. I am so so grateful, and so very happy, and tomorrow’s the last day of school before March Break and it feels like, instead of being stuck or in a spiral, we’re marching forward, forging new paths. Finally, finally. What a long, long road it’s been.

February 14, 2023

Swimming in Pee

We had the kind of weekend this weekend that hasn’t been possible in such a long time, the kind of weekend that we were wondering if we’d ever have again, even just a year ago, and it felt really good, to be so full of joy, our time full of fun, everything carefree. And something I can write on my blog that I would be less comfortable posting to social media, which is so much more amplified and devoid of context, is that we thoroughly forgot about Covid this weekend. 24 hours in Niagara Falls, staying in a hotel, visiting an indoor water park, and eating in restaurants—the object was enjoying ourselves and beyond packing hand sanitizer, we were going to not worry so much, leave our masks in our pocket for once.

Which I know is something we’re very lucky to be able to experience, but anyone who reads here often also knows what a terrible time I’ve had with anxiety over the last few years and how Covid absolutely fucked with my brain, made me think that keeping our health system functioning was my personal responsibility, and that every single one of my actions was so gravely consequential that I eventually was unable to do anything except walk around weeping at the sadness of it all, crumbling under the weight of this imagined burden of personal responsibility and my own catastrophic thinking. It was really bad, and terribly debilitating, and also really freaking hard for my family, and no doubt my kids will be talking about this in therapy for decades to come.

(I really really hate the way that bad actors hijacked the conversation around the pandemic and mental health right out of the gate so that it became impossible to have good faith conversations about any of this, to acknowledge that Covid is real and threatening, but also that there are dire consequences of having an entire society living under a perpetual emergency for literally years.)

And so it was actually really important, and even healthy, to have this little holiday away from it all, a bit like tearing off a band aid, pushing myself out of a strange uncomfortable comfort zone. If we got sick this weekend, we reasoned, so be it. Which is the kind of gamble that’s always been necessary for a trip to an indoor water park anyway, right? We were pretending that there was no circulating respiratory viruses, just as we were pretending that the wave pool wasn’t populated by people (hopefully mostly just the small ones, which is somehow less disgusting!) who were freely urinating without compunction.

So naturally, my youngest child woke up this morning puking—an inevitable water park aftermath. (She has been well since mid-morning, however, and will likely be returning to school tomorrow.) And then I headed to the hospital for my annual thyroid check, where it was found that one of my nodules had grown larger and so I had to have a biopsy (which I have had fairly often, and they’ve always been benign, thankfully), cystic liquid being sucked out through a needle in my neck.

And in the lab where I was sent for routine bloodwork, the technician was dressed in red for Valentines Day, just like I was, and we remarked on how we matched my blood, which filled four small vials for testing, and it somehow seemed fitting on Valentines Day, it being about hearts and all, my heart and your heart doing the amazing work of keeping our remarkable blood pumping through our gross and awesome bodies, and how all of us are connected, for better or for worse, most irrevocably.

I took the subway to the hospital for my appointment this morning, the first time I can recall riding transit at rush hour in such a long time, and the subway cars were packed, and more people than not with masks on, including me, and far more people with masks on than I ever see at off-peak hours (which makes a lot of sense!), and the subway was also so audibly quiet, people possibly on alert and good behaviour due to recent acts of violence on transit, and maybe that calm and quiet was what made it a little extra easy to feel in love with everybody today. All these people who’d woken up and had their breakfast and gotten dressed, and maybe nursed sick kids, or walked their dogs, or watched the sunrise with a cup of coffee, and now they’re out in the world, surrounded by strangers, following the rules, going through the motions, minding the gap.

It isn’t necessarily how badly our society functions that is remarkable, all of its faults and flaws, as I’ve written many times before, but instead that it functions at all. That most days in this city hundreds of trains take people places, and those people make room for each other, and move over on the stairs to let others pass, and help somebody up who has stumbled and fallen. That lab techs who dress up in red to make someone’s day a little brighter, going to work to poke needles, drawing blood, performing work that just might mean the difference between life or death. The miracle of socialized medicine and that I get the care I need to stay healthy. The miracle of ultrasound. The mask I continue to wear, when it makes sense, in my day-to-day life, and the knowledge that all of us, always, are swimming in pee.

And somehow, this is love.

This is life.

Happy Valentines Day.

November 14, 2022

Palmerston

On Saturday we didn’t have a lot going on (a treat in itself), but I had to buy some berries (in preparation for guests on Sunday for whom we would be making breakfast, a friend and her beautiful family who we haven’t seen since 2019!) so we all walked over to Gold Leaf Market at Palmerston and Bloor (which is always the first place in the neighbourhood to get fresh rhubarb in the spring), and we decided to also stop by at the library. All these parenthesis, I hope you’ll understand, underlining the resonance of what I’m talking about, these local streets we’ve been circling through these difficult years as we’ve walked our way toward better times. No trip down the street is ever a straight line.

There are places we walked in the Covid times where we can’t bear to walk anymore—the small patch of woods at the university, the grubby little ravine just south of St. Clair and the ravine proper, any back alleyway and don’t even care about the garage door murals, nope. We walked those walks to save our insanity, and only managed it, JUST, or maybe we really didn’t, which is why we refuse to do it now. Nobody in our family can stand ice skating anymore, not that we really liked it very much in the first place.

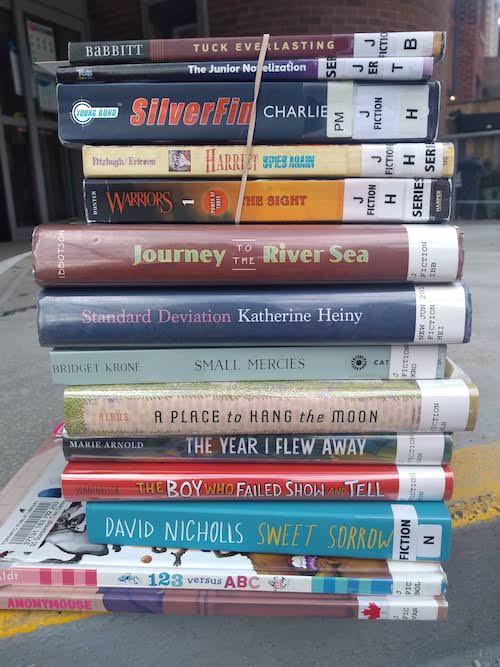

Palmerston Library, however, is very different. A Covid destination for sure—our home branch was closed for a very long time beginning in 2020 and when the library reopened for circulation that summer, our holds were routed to Palmerston, which was the next closest—but it represented something different than walking in sad circles and feeling hopeless. I remember going to pick up a stack of books we’d requested and getting rhubarb on the way that spring and thinking what a miracle were both these things, how we were truly lucky.

“Remember when we had to put our cards on a tray?” I asked Stuart, and there was fondness to these memories, instead of despair. When the library opened again, we’d go pick up our books at the front door where plastic barriers were set up, and we’d hand over our library cards on a plastic tray that was slid back to us at the end, all of it slightly illicit, like a speakeasy, except books instead of booze. There were some weeks where going to pick up our library holds was the only item on our agenda, and so it was a big deal, and the librarians inside found even more ways to bring the books to us—there were grab bags geared to different age groups and genres, and also new releases in the window, each one numbered, so you could request the numbers you wanted, and somehow I ended up getting my hands on all kinds of new releases, like Beach Read, by Emily Henry, and The Girls Are All So Nice Here, by Laurie Flynn, and Sweet Sorrow, by David Nicholls, which I only chose because I liked the cover but I really really liked it.

I love to think about all this, about the treat of these wonderful novels in such a difficult time, about how much it meant to have a destination and not be aimless, and also about adaptation and ingenuity and the amazing ways that library staff found ways to make things work. (Remember when all circulating materials had to quarantine for a week before going out again, which meant it took SO LONG to get a book in demand, and also how we eventually determined that Covid was not being spread by library books, which was wonderful news?) I love to think about all this because it’s a story of trying things, daring to be different, of how much libraries and books meant to our communities, of being brave and taking chances, and how some of those chances work out exponentially (by which I mean that I am probably FAR from one of the only people you’re going to meet who think the library helped save her life).

Eventually, we could go inside again. I recall that we weren’t permitted to browse, but could pick up our own holds, and that computer terminals were available for those who needed them. I remember the first time I walked into a library again after so so long, and how I could have cried, and maybe I even did, because I was moved a lot in those days. And then when we could go back again and select our own books from the shelves, a little further down the line, and masks were required, though there would often be someone who didn’t have one (usually a person who was having other kinds of trouble), and we learned to be okay with that, which wasn’t easy, but it became easier, an essential lesson in sharing space with other people and how we can’t always (ever?) be in control of what other people do.

Our home branch opened again, and what a thing, and I can’t even remember when that happened, because it was just so ordinary, to stop in and pick up our books on the walk home from school, the kind of luxury I’d never thought twice about before, but it felt so wonderful after so long, and of course, things were not so straightforward. There was a while when our branch closed, and we were back to Palmerston, two steps back—albeit without the book quarantine and speakeasy card slide, so this was progress. But not every setback is a total disaster (something I often have to remind myself about after what we’ve all been through), and our branch reopened, and it had been such a long time since I’d been to Palmerston Library until this weekend.

And—unlike so many other things—it felt good to remember.

October 19, 2022

On Being Wrong About the Pandemic

For a while now I’ve been obsessed with the idea of what we’ve, collectively and otherwise, got wrong during the pandemic, an obsession that has manifested in conversation, direct messages, ideas about some sort of a Q&A project with political types (what a [n impossible] thing it would be to receive honest answers to the question of, “What did the pandemic teach you about the limits of your ideology?”), and thoughts towards a blog post that would definitely outline the numerous times I took things far too seriously, including the weight of my own actions, and that we probably could have spent Thanksgiving 2020 with my mom.

Last year Vivek Shraya published a short book (it was originally a talk) called Next Time There’s a Pandemic, a book I enjoyed, though it wasn’t enough “You’re Wrong About…” for me. (It was also conceived with the idea that two and a half years in, there wouldn’t STILL be a pandemic, so that was not the book’s fault, exactly…) But once the book was read, I wanted more interrogation, more reflection. In general, Shraya’s book aside, I wanted a whole lot less of, “Well, we did the best we could with the information we had in the moment,” partly because, while this is true, I think too many people have spent the pandemic being wrong over and over again.

Also because it’s been impossible for any one of us to get this exactly right, which has been one of the hardest things about the pandemic, the absence of concrete guidelines, rules to follow to the letter, because the mark of Covid-19 has been how it doesn’t follow rules at all, is as inconsistent as all get-out. It’s mild and it’s deadly, and in your gut and your respiratory system, and it doesn’t affect kids much and it makes kids really sick, and the vaccines are effective and they’re not, and it’s airborne/very contagious and you never got it, and it killed that healthy 32 year old but that asthmatic woman who is 106 was fine.

So anyone who thinks they got it right every time is wrong about that, which is only just the beginning…

And what I’m wondering about now is why all this means so much to me, why I need other people to join me in admitting when we’ve been wrong, where our judgment has fallen short, even when we were doing our best.

Partly because I think it’s really interesting…

And of course, I also think it’s important to celebrate what we got right—I’m so proud of my community in all kinds of ways [see “About Last Spring: The Vaccine Narrative I’m Holding Onto”] but this celebration is only part of the picture, which seems important after a long time in which neighbours have felt so divided. And while the fact that more than 80% of Canadians stepped up to be vaccinated absolutely means there is far less division than all the noise would suggest (truck horns are very loud, this is true!), I think that making space for everyone to reflect on what they got wrong (without shame or judgment) creates space for reflection for those people who might benefit most from a bit of that thoughtfulness.

I think too, if we’re getting pathological, this means so much to me because of control issues, a strange compulsion to be certain about uncertainty…

But mostly, I think that acknowledging where we were wrong is to acknowledge our capacity to learn, to grow, to adapt and be flexible, traits that will prove to be our greatest assets in societal challenges that lie ahead of us.

July 22, 2022

Freudenfreude

Freudenfreude (finding joy in other people’s pleasure) is truly one of the best habits that I’ve managed to get out of this pandemmick, and lest you think that I’m being repulsively sanctimonious right now, I can promise you that I am also well acquainted with freudenfreude’s much less salubrious evil twin (although I aspire to be better than that, and even sometimes succeed). But there was a time, when things were really rough and uncertain, that if I hadn’t figured out how to be happy for other people, I wouldn’t have been able to be happy at all, because there just wasn’t a whole lot of goodness going around.

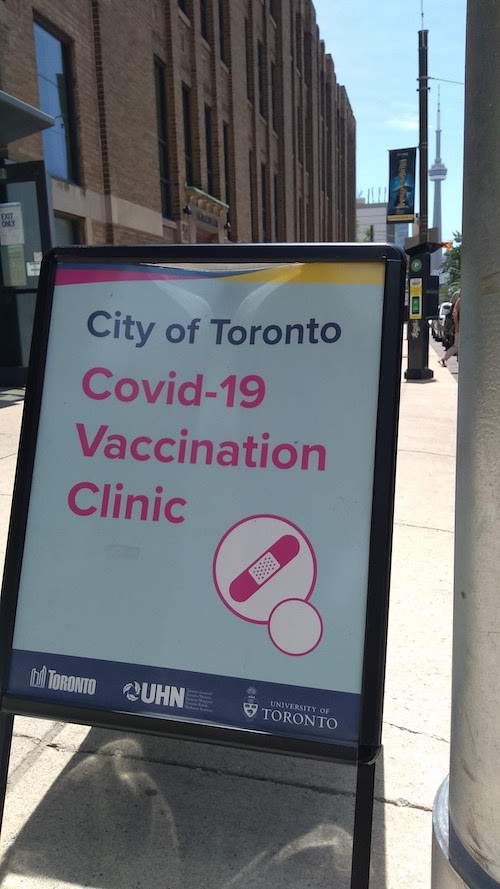

This was about a year and a half ago, when the pandemic fatigue was real, and vaccines were only just beginning to happen. The very first person I knew who received a Covid vaccine was a friend who is a first responder, and we made him a card, delivered it to his house, because we weren’t going anywhere else, and had all the time in the world to do so. I wasn’t sure when I would get my own shot—predictions were for September 2021, perhaps?—but he needed immunity far more than I did, and I was happy for him, and for all the other people who love him who’d get to worry a little bit less. In a time that was rather bleak, this was a very good day.

And then friends in America started getting their vaccines, and I started saying, “I’m so happy for you!!” when they posted about it on social media. Partly because I was happy for them, but also because I’d come to realize that it didn’t really matter who was getting vaccines exactly (obviously it does, vaccine equity is a thing, and access is far from fair, especially on a global scale, but see, I was practising being magnanimous) because a shot for any of us is a shot for all of us. It helped too that those early glimpses of vaccine rollouts were a harbinger of similar goodness coming for us down the line. (I’ve felt the same seeing US kids under five getting their shots, knowing that so many families in my own community are going to be feeling the relief of having their own small children vaccinated very shortly!)

Possibly the root of my freudenfreude really is selfish after all, or maybe just not only altruistic, because I really do think we all win in a world in which good things happen and people get what they need. (I remember reading in Tara Henley’s Lean Out about how wealth inequity even made wealthy people less happy, because who wants the world surrounding them to be going to shit?)

Also being happy for other people was such a better feeling than what we’d all been through over the previous year, when you’d see someone on a playground swing, for example, and become enraged at the way they were putting lives in danger. When people were furious at twenty-somethings for sitting in the park. I was finished with the self-righteousness, with the shaming, and altogether tired of having the joy sucked right out of my life, and so every bit of goodness someone else experienced shone a little light upon my world. Family reunions, holidays, exquisite cakes, backyard pools, masked gatherings with friends six feet away in the garden—I was there for it. I was THRILLED for you.

It helped that I was finding my own small pleasures, going out of my way to care for myself and the people I loved. I knew what it meant, is what I mean, the hugeness of these small bits of normal, pleasure and connection. I felt it too.

When we FINALLY arrived in England in April, two days after our cancelled journey in March 2020, after such a long road, so much sadness, stress, and bother, a lot of people in my circles were feeling the freudenfreude, because they told me so. So many people were so happy for us, because they knew what that trip meant after what we’d all been through, how wonderful it was to connect with family again, to have any kind of a getaway after so much loss and anxiety.

It wasn’t just a trip. Nothing is “just a” anything anymore. A child’s birthday party in the park, dinner in a restaurant, being there when your grandfather blows out the candles on his birthday cake, a picnic with old friends, cousins playing together, sleepover parties, backyard bbqs, a trip to the movies, a day at the beach: I am so so happy for you.

And I am so so happy to be happy for you.

June 23, 2022

A June like all the other Junes

It’s been three years since we’ve had a June like this June, a June like all the other Junes before it. My kids walking to school in shorts and sandals, spring light shining through lush green trees into their classroom windows, and the calendar packed with dates for the school picnic, school dances, graduation, and end-of-the-year trips. If my email inbox is any indication—packed with calls for bake sale contributions, teacher gift collections, volunteers and chaperones—nature, as they say, is healing.

If all goes according to plan in the next week, the 2021-22 school will turn out to have been something close to normal, two weeks of virtual learning aside, albeit with two-thirds of it spent in cohorts, high schoolers in those ungainly “quadmesters,” the experiment that has been hybrid learning, and mask requirements. Some of these strategies for reducing infection have been more effective (and less disruptive) than others, but I’m grateful for those that worked, for the gift of vaccines, and for the incredible dedication of teachers and school staff which has meant our kids get to go to school every day, see their friends, learn in person, play at recess, and all the other normal things that all kids should get to do.

As a parent in Ontario, a province whose children have spent more time out of the classroom since March 2020 than anywhere else across the country, something close to a normal school year is a gift I will never take for granted.

But I also remain frustrated that too many voices—some of them prominent, loud, and speaking with real authority—have spent the last two years and more insisting that such success was unachievable. These failures of imagination have had real consequences for children and families across the province, and served to undermine progressive values, faith in public health, and the possibilities of our collective efforts.

In 2020, however, some of this seemed understandable. So much was still unknown about Covid-19, with limited medical treatments available, and vaccines far off on the horizon. And so, even as students across Europe began returning to school in the spring of 2020, students in many Canadian jurisdictions would finish up their school year online, in Ontario this setting a most unfortunate precedent.

It didn’t help that bad-faith actors came to hijack the conversation so that questioning restrictions like school closures started to seem like possible shorthand for not taking the Pandemic seriously. Or that our media was so US-centric that it was hard to see examples of Covid being managed any way but terribly. It didn’t help either that, in Ontario, the government was slow-moving on measures to improve school safety, and then rolled out a program for virtual learning that made parents feel like they were being forced to pick between two not-great choices. To complicate matters further, by September 2020, Ontario was coming out of a year of labour disruptions by teachers and school staff, which meant tensions were high and political rifts deeper than ever. In particular, I recall a tweet from exclusive private high school St. Michael’s College School, of which Ontario Education Minister Stephen Lecce was an alumnus, spotlighting gleaming new handwashing stations and plexiglass room dividers. Meanwhile public school students were being promised six feet of distance between desks in classrooms where there was literally not enough space to accommodate such dimensions—the disconnect was pretty staggering.

Sending my children back to school September 2020 was a nerve-wracking endeavour, but it was a choice whose risks we felt comfortable taking since no one in our household had a health condition that made them vulnerable, my husband and I both working from home meant our chances of spreading the virus were low, and—I think, most essentially—because we were already well connected to our local public school whose staff we trusted absolutely to help keep our children safe.

But we were still nervous, and I soon realized that I would have to quit Twitter in order to have my kids attend school without my mental health being compromised, because all the voices on that platform—from doctors, and people who thought they were doctors because they followed doctors, and activists, and politicians, and pundits—were just too much for me to handle.

I also ended up leaving the several parental advocacy groups I’d followed in previous years to show my support for public education, mostly because they too were piling on the Twitter hyperbole and using every opportunity to get a shot at our ding-dong government. (The thing about ding dong governments is that you’re always going to get a shot, so you actually have to be discriminating at going about it or else it stops having meaning.)

The low point, for me, came when I sent a DM to a representative from one of these groups, which was then keeping tabs on daily case counts of Covid cases reported in Ontario schools. (A number that was, in retrospect, so low that it almost seems quaint now.) And I inquired to the representative as to whether they were perhaps stoking fear and anxiety in sharing these numbers outside of the context of what a small proportion of students these cases actually represented, and—even more important—that school spread really didn’t seem to be a factor.

“Let’s engage with reality, rather than just trying to push your narrative, because that undermines your credibility,” was basically what I was saying, but this person was uninterested in that. Responding that the numbers were likely undercounted anyway, and that I was being ableist and racist in denying the impact of Covid, since it disproportionately affects the most vulnerable in our communities.

The latter point most certainly the case, but doesn’t that just underline the importance of dealing in facts and not engaging in inflammatory rhetoric? Because the stakes really are that high.

You’d think people might have learned something from September 2020, when schools reopened and everyone lost their minds, but we didn’t. In Ontario, schools closed again after the Christmas holidays, students returning to their classrooms for about six weeks, and then schools closed a second time after delayed spring break. I recall commenting on Facebook that it might be nice if schools could just reopen for a few weeks in June for just a bit of closure, so we didn’t just keep adding to the trauma of everything having ended so abruptly two years in a row, and other people shouted my point down. It just wasn’t worth the risk. It wasn’t possible, they reported with a glib kind of nihilism. People who lived in Twitter far more than they actually went out into the world telling me how it was, because they’d seen it in their timelines.

Children returned to school again in September 2021 with a virulent new strain on the rise, and again in January 2022, and each time I couldn’t help but think how advocates and experts had squandered so much of their capital by making something massive out of the challenges of September 2020. So that by the time spring 2022 rolled around and everything was so much worse, nobody was listening to them anymore. At a moment when advocacy was necessary, most normal people, altogether pandemic-weary, had tuned it all out. Because of the Public Health Twitter star whose open letter in January 2022 predicted “sudden mass infection” and effects that would be “catastrophic.” The people who’d decided that medical experts advocating for schools to reopen were in kahoots with Doug Ford and developers to destroy the green belt. The hysterical Instagram power-points warning when children returned to school after March Break, “STUDENTS ARE GOING TO DIE. TEACHERS ARE GOING TO DIE.” Until the messaging was just as uninformed and divorced from reality as that of anti-vaxxers.

It’s not that people were wrong that bothers me. Surely all of us are glad that the most dire predictions regarding Covid-19 often did not come to be. I understand too that this has often transpired because of urgent messaging which led members of the public to change their behaviour, changing trajectories for the better. It’s how public health is supposed to work.

But I am bothered by the lack of reflection by people with prominent platforms. I am angry that a curious combination of cowardice, defeatism and self-righteousness led to children in our province being out of school for months during periods where we were free to eat and drink in bars and restaurants. I am angry that the same people were wrong again and again, and that all those same people are still furiously tapping away at their Twitter feeds, never once displaying an ounce of humility or contemplating the remotest possibility that not everything is going to end in disaster.

All this matters because we live in a moment of enormous challenge on a variety of fronts, and our society is certainly never going to be able to meet these if how we grappled with Covid in schools is the precedent. If our most prominent voices continue to be steeped in cynicism, egotism, more adept at criticism than anything constructive, more concerned with amplifying their own voices, messages, and political agendas than actually listening, and learning, and figuring out how together we can make things work.

Because we can make things work—the success of 2021/22 is a testament to that. And I don’t know if it would be so unwise, when the next big crisis rolls around, if we just let school teachers and staff be the ones to tell us all how to solve it, and everybody else can be quiet for once.

May 2, 2022

Bridge

I got Covid last week, and the whole experience takes me right back to pregnancy and early motherhood in way that narrative can be imposed from without when we’re most vulnerable.

And also how resistant I am to being vulnerable.

I’ve never liked being told who I am, or what is my destiny. I have no interest in numerology, or my enneagram, or Tarot. There is a part of me that’s ever resisting the idea that I’m not singular, that I’m one of the others, even though I know that I am the others. All I want is for there to be a little room for me to figure things out for myself.

Maybe I just really hate anybody telling me what to do?

I remember being that insufferable though when my kids were small, on both sides of the equation. I remember all the people who smugly smiled and said, “You’ll see!” and how I was so sure that I’d show them and do it differently (and sometimes I actually did). I remember too coming through the other side and how I’d perilously managed to piece my shattered universe back together with ragged pieces of scotch tape, it seemed like, and all these lessons I’d decided I’d learned so painfully so that other people wouldn’t have to. All the advice I imparted, literal Excel spreadsheets in regards to baby books, and sleep schedules, stroller models, and baby carriers. None of it really of any use to anyone else. Such a lesson in subjectivity, but one that it took me a long time to learn.

A month ago, when many people in my circles started getting Covid, I got my hackles up. Partly because I REALLY wasn’t in a place to accept getting Covid, because we were on the cusp of a trip to England that had already been cancelled once due to Covid. Nope, we weren’t going to get it. We couldn’t. And we didn’t, thank goodness, thanks to avoiding places like crowded airports and jet-planes. Though I was paying attention, people I know on social media sharing their stories, providing daily Covid updates. I went shopping and bought a whole of stuff like Lipton Cup-a-Soup and Vicks Vapour Rub, imagining these as a kind of insurance. If I had them, I wouldn’t need them at all.

And mercifully, I didn’t. Not until we were home again, and the stakes weren’t as high. We’re all vaccinated and boosted. and if Covid’s inevitable, now’s as good a time as any. I suspect the airport and the jet plane are what did it, Canadian customs with officials yelling at us to bunch up together in the lines, all those people whose masks were hanging down below their noses. “If I can see your nostrils, then what’s the point of your mask?” I sang, not loud enough, half-delirious after twelve hours of travel.

Three days later, Iris woke up with a fever. The test was positive, but we didn’t need it to know. And it’s been fine, Covid not so much “ripping” through our house, but creeping through on tiptoe. Iris had a mild fever for part of one day, was a bit congested for a day or two after, but mostly was back to normal and bored until she’d returned to school after five days of quarantine. I developed cold symptoms last Wednesday, symptoms identical but much less severe to another cold I’d had to January, an affliction I’d been hesitant to label as Covid because that seemed like tempting fate—it had been too easy. Though I hadn’t tested then, because we’d all been locked down anyway, and there was no place to go, and our apartment doesn’t really have a proper place for someone to isolate. In January, at least, nobody else got it.

This time we’ve all got it, but it’s been mostly just relaxing, everyone’s energy a bit depleted with cold symptoms, but nothing worse than that, thank goodness. Everyone’s eating normally, albeit more popsicles than usual. Nobody’s really suffering at all, and I’m so relieved by that—to be fine enough to sit around reading. To not be confined to my bed for days at a time with muscle aches, and fever dreams, all those things I was dreading. (I had a terrible bout of pneumonia in 2015; to have to go through that again, with everyone around me sick, and fears of mild cases getting worse—I didn’t want any of that at all.) We’re so lucky. This is definitely okay. As best scenario Covid stories go, this is the next best thing to being asymptomatic.

But am I doing it again? Not being the others? The way that in the early days of motherhood, I would sometimes fancy myself as rocking it, not having to contend with what everybody else is going through. Am I being Covid-smug with my stuffy nose? Like one of those people who lose the baby weight in a fortnight?

And oh, the inapplicability of everybody else’s advice. Even though I know they’re just trying to be helpful, but it seems strange sometimes to be inundated with tips by people who think their own experience applies to everyone, people who have no idea what you’re going through. (Of course, I do this too.)

The subjectivity of Covid is one of the few things I think we can properly take away from all of this—in addition to “Wash your hands.” The danger of thinking, “I know exactly what you mean.” That there isn’t a gap between your experience and mine. I’m not saying we can’t bridge it, but it’s important just to acknowledge that it’s there.

April 25, 2022

The Fell, by Sarah Moss

I am besotted with Sarah Moss’s slim and haunting stories, beginning with Ghost Wall, and then Summerwater, and now, her latest, The Fell, which I read on our plane journey home from England. (Interestingly, the one book I’ve read by her that wasn’t slim [Signs for Lost Children]) I didn’t like at all.)

Our plane journey home from England took place one year from the day that my husband and I received our first Covid vaccines, and while things since that day have not unfolded as neatly as we would have hoped, to have this long-awaited journey finally happening seems like the most fitting anniversary, and I just feel so tremendously lucky.

I think it’s easy to forget how many lifetimes have been contained within the last two-and-half years, so many plot twists, so many steps forward and two steps back. The idea of the pandemic is like an ever-looming dark cloud overhead, even though the reality of the experience has been much more textured, layered, unfolding, and even interesting. Interesting especially because the lack of certainty has been unmooring in fascinating ways, even while people stand resolute in their respective camps. (Whatever news sources you read, whatever your beliefs about vaccines–it’s all a story you’ve been writing alongside other people you trust about what this thing is and how it should shape our lives (or not). And in many ways, The Coronavirus has become a host story for a million other parasitic stories–our politics, our most intimate tensions, our economic ideas, our religious values, our parental aspirations. What a heavy frickin’ story, y’all. What a weight.)

Something that has helped me a lot in the last two years has been paying attention to the ways that life goes on in other places where Covid responses were different from ours here in Ontario—a former classmate in Shanghai, friends in New York City, my sister in Alberta, my husband’s family in the UK. The awareness (which I’ve written about before) that there really hasn’t been a way to get it right, that a virus is a formidable foe, and that most of us are just muddling through and doing our best under leadership that’s not necessarily nefarious (Boris Johnson’s lockdown birthday parties, notwithstanding).

It was interesting to be in England last week, which has decided to be finished with Covid altogether, where every fourth person we passed on the street had a hacking cough. I don’t think that doing away with Covid restrictions altogether is the right thing to do, but I also don’t really know what the right thing to do is, and I know we’re a public who has definitely lost our appetite for extreme lockdown measures. (Also, my youngest child testing positive for Covid yesterday, and her symptoms were a few hours of a low-grade fever and a runny nose, all of which have dissipated, and the rest of us continue to test negative, be symptom-free, FINGERS CROSSED. Hooray for vaccines.)

The Fell took me back to a different time though, when the skies were emptied of planes and the jury was still out on washing your bananas with Lysol. It’s November 2020, and Kate—single mother, waitress on furlough—has been quarantining at home with her teenage son after a Covid exposure, and suddenly decides that she can’t take it any more. And so off she goes on a walk on the fells near her home in the Peak District, strictly against the rules, even though the chances of her running into anybody else are nil. The trouble arises when she doesn’t come home.

Do you remember being irate about the idea of people leaving the house more than once a day for exercise? I sure do! Considering perhaps that even that was excessive? The sheer irresponsibility of young people gathering with their friends in the park!?!? An adherence to “rules” instead of any kind of pragmatism. In April 2020, I ordered a bouquet of flowers from a local business because somebody in my Facebook feed was squawking that any kind of “unessential” purchase was putting lives at risk, and I needed to defy her. Sometimes I was furious at the scofflaws, sometimes I was doing the scofflawing myself. All of it was so annoying, and much of it continues to be so.

The Fell is told from the perspectives of Kate, her son Matt, her elderly neighbour Alice (who’s had cancer, and therefore is considered vulnerable, in need of protection, and thus abandoned to her own company), and Rob, who works in Mountain Rescue and is called upon to look for Kate when her son reports her missing.

So much of the arguments against lockdowns and Covid government regulation has been so terribly idiotic that we’ve been deprived of the opportunity for proper reflection on what these responses have been. On what has indeed been their fall-out, the depravity. I think of elderly people left alone in care homes for months at a time. Of the mental health toll. Looking back, the fact that children in Ontario had to isolate for ten days each time they were exposed to Covid via a classmate seems needlessly excessive. The fact that small retail shops were closed for months in 2021, undermining faith in public health measures in such a dangerous way. It’s all be a lot of not great.

And yet the number of people whose response to this madness was supporting wannabe fascists?

It’s enough to make one’s head explode.

The Fell, however, is in lieu of that. A novel about risks and consequences, about community and isolation, about what it really means to protect each other, to save each other. About the risks of life itself, and what it means to take those risks, and unlike so much of the current discourse, it doesn’t offer easy answers. There are no easy answers, but asking the questions is the point.

March 31, 2022

Loopy

The past two years have, in some many ways, had me feeling as though I were caught in a loop, and such feelings were really what drove me down in December. I remember feeling devastated by posters around my neighbourhood—a local church had organized a Christmas Eve carol sing, and now all the posters had stickers pasted over them that said, “Cancelled Due to Covid.” A friend’s child was playing music in a local show, and that event got shut down. Once again, so many plans were shifted, just when we were beginning to think it was time to venture out into the world again. It felt like a trick.

One of my favourite things about right now, even with case counts rising locally, is how far away most of us are from that moment in which the idea of other people having fun made everybody furious. As Miranda Featherstone writes in today’s New York Times, “I am tired of judging the Covid choices of strangers.” I got tired a long time ago. For the last year, as vaccines arrived, I’ve been overjoyed to see my friends returning to the activities and pursuits that define their lives. Even sports. I hate sports. But I’m overjoyed at the sight of a packed stadium, and not just because I don’t have to be there. It means the world. It means connection. I welcome every little bit of it.

And in some ways, even with the infernal loop of decline and rise of case counts, things are starting to feel a bit less loopy? That friend’s child got to play their show the other week. Plenty of pals went away for March Break for the first time in three years. The cookbook writer Emiko Davies, who I started following on Instagram in March 2020, when Italy (where she lives) went into lockdown, has finally travelled to Australia with her children to see her parents. All these people I don’t even know—Sarah Harmer’s FINALLY getting to go on tour for her album Are You Gone? There is a week in May when I’m going to two evening concerts and a theatre matinee!

I love it. I’m here for it. Get vaccinated and booster, put on your fucking mask, and let’s do it.

On March 16 2020, we were due to fly to Manchester to visit my husband’s parents, and our one-year-old niece. My husband’s father was very ill from cancer, which made this trip especially pressing, and I still remember, the week before our departure, talking with my dermatologist about how it was going to be fine, and it was Italy and Iran that were the hot-spots. I remember how stressed out we’d been the week before that, riding the TTC and anxiously applying hand sanitizer, and how I’d shout at my children not to touch anything. They just couldn’t get sick. Because a pandemic is very a bad time to be flying across the world with a bronchial infection.

But of course, we didn’t go at all. That week following my appointment at the dermatologist (the last crowded waiting room I ever sat in) was one in which we all lived through about a decade of shifts and radical change, it became clear that travelling at this moment would not be responsible, and it would have been halfway through our time in the UK anyway in which the Prime Minister would have implored us all to come home. It would have been stressful beyond belief, and I know that cancelling our trip was the right thing to do that moment.

Two weeks from today, we’re scheduled to try again. And in some ways that is driving me crazy, especially as case counts rise. As though I were the centre of a sci-fi plot and this elusive trip to the UK a destiny in front of which the universe is determined to throw up walls, make impossible. Like Natasha Lyonne in Russian Doll every time she tries not to die. (Cue Harry Nilsson).

Although I even have a rational side that knows it’s probably going to happen. (!!) And knows too how wondrously cathartic it’s going to be when it finally does, to finally break the spell, to close that loop. Fingers crossed.

March 24, 2022

Thinking About Masks

(Background: Ontario began lifting indoor masking requirements this week, after nearly two years.)

I am very pleased every time I see that a business is continuing to require masks in their establishments, not because I am wedded to masks per se, but instead because I fully respect the rights of other people to feel comfortable in their workplaces and to make such calls that feel right for them, and I’m so happy to accommodate that in my day to day life.

Because masks aren’t hard.

The whole masking issue is made simpler for me anyway, because while I’ll agree that, in general, the risks of Covid are quite low right now (cases tend to be mild), and perhaps it doesn’t make sense for everyone to mask up for an illness that leaves most people feeling crummy for a couple of days, the stakes are different for my family at the moment, three weeks out from plans for a big trip that was already once cancelled due to Covid and we’re just absolutely desperate for it to happen this time.

Basically, we can afford to get sick right now.

Though even if we didn’t have plans to travel, I suspect I’d continue to wear masks in indoor spaces. Because, as I said, masks aren’t hard. Especially since there are vulnerable members of our community who can’t afford to get sick ever. Especially since I don’t think that wearing a mask is more difficult than being sick is. (I had pneumonia in 2015 that left me bedridden for weeks and was the most physically devastating experience I’ve ever had.)

I am looking forward to a spring with travel plans, and tickets to plays and concerts (!!) and to me wearing a mask is just one more way to ensure that any of this is actually going to happen. (OMG PLEASE!)

While I am very pleased every time I see that a business is continuing to require masks in their establishments, however, I know this isn’t going to be universal, and I’m trying to ease myself into the fact that this is okay. I’m trying to ease myself into the fact that we’ll not be wearing masks forever, and I don’t want to be wearing masks forever, and there are plenty of smart and good people I know who are thrilled about the end of mask requirements, and they might have different priorities, understandings, or experiences of all this than I do.

As with everything during the last two years, there is no one right answer to the challenges of the current moment, and I continue to find that interesting.

Though I am sorry about all the bad actors and loudmouths whose efforts have made understanding this particular point of view incredibly difficult, who have turned the lack of a mask into something aggressive and threatening when I know this isn’t necessarily the case. But it’s hard to think otherwise living in a neighbourhood that, for example, has put up with two years of unmasked jerks barging into shops and confronting employees as a political stunt as part of weekly anti-public health rallies. Who have been the ones who turned masks into a symbol, when all along they have been a tool, an incredible tool that’s meant I’ve been able to ride public transit, do my grocery shopping, send my children to school, and so much more.

In a way, I am most grateful for the end of mask requirements, because it’s going to mean the end of somebody not wearing one being perceived as an aggressive act of political defiance. Because I find all that so sad and disappointing, and I’m just tired of that. I continue to be baffled that two years into a public health emergency, there are people who’ve constructed entire identities on the basis of not caring for others. Which is separate from the other people who’ve tied themselves up in knots to convince themselves that rejecting masks and vaccines is actually what caring is, because it’s the masks and vaccines that are the true danger, these people having proven themselves to be particularly susceptible to misinformation. It’s all very exhausting.

(Have you ever smiled at a baby while wearing a mask and the baby has smiled back at you? This has happened to me. I’m no scientist, but I can tell you that masks and vaccines have hindered my children’s health and development not one iota. The overstatement of harms from these tools have made it impossible to have any real conversations about any of this.)

I have worked really hard to not to make my mask part of my identity. I have worked really hard to be flexible, not married to consistency (because Covid certainly isn’t!), and to be open-minded, and not histrionic or hyperbolic in my discussions around any of these issues. I have been bothered that as we move away from public health restrictions, many of the same people who’ve been fervent public health supporters over the last two years are losing faith because new public health guidelines aren’t necessarily those they agree with. I’ve found it interesting over the last few months that there’s been an overlap between anti-vaxxer parents and super Covid-cautious parents—they’re all threatening to take their kids out of the education system, insisting the public health decisions are motivated by nefarious factors, deciding that small risks are worth undermining general public health for.

Something else I find interesting is people insisting that their perspective on all this is stemming from justice, from community care, but the end result of this is that they’re just absolutely furious with a lot of their neighbours, which is kind of ironic.

I have to keep reminding myself not to imagine that I’m morally superior to the people who disagree with me. And not just because it’s morally superior not to think that you’re morally superior, but also because I’m not, and neither are you, and all of us, at our best, are just trying to muddle through, to figure this out together.