March 3, 2017

Little Blue Chair, by Cary Fagan and Madeline Kloepper

Little Blue Chair, by Cary Fagan and Madeline Kloepper, is the kind of book you finishe reading with your family, and then there’s a split-second of silence which will be broken by someone saying, “That was a good one.” Everybody’s nodding.” It’s a familiar story, the kind we’ve read so many times before, but it’s just so deftly executed that you’ve got to admire it. And there’s plenty else to admire about it besides that.

It’s a something-from-nothing circle-of-life tale, and at its centre is a chair. A little chair, the kind you must contort your body into if you’re visiting a preschool, but this chair belongs to Boo and it’s the seat of his imagination. Fagan shows him using it to read, to build forts, to climb on, and he even falls asleep on it. (He sits on it too.) When Boo outgrows his chair, his mom puts it out on the lawn with a sign that says, “Please take me,” and therein because a most excellent adventure.

Do you ever wonder what happens to the things you put out at the end of your driveway? We’ve gotten rid of an antique bed frame, a busted stroller, a repulsive carpet, a trundle bed, a futon frame, a decapitated rocking horse, and several other objects that way. Moreover our coffee table, desk chair, and many other items in our household joined us in a similar fashion. After reading The Little Blue Chair, I’ll never imagine an item’s narrative trajectory from curbside as anything normal again.

A rattling old pick-up comes by and picks up (of course) Book’s chair, and the drive sells it to a junk shop. A woman buys it and uses the chair to sit her plant pot, but then the plant grows up, she plants it in the ground, and doesn’t need it anymore. And so back out to the curb it goes, where it gets picked up by a sea captain who uses it to have his daughter sit beside him as they sail across the ocean. When they’re finished with their journeys, the leave the chair on the beach, where a man finds it and uses it to give children rides on elephants.

And so on and so on, the most extraordinary travels, through the postal system and up a tree, and round and round on a ferris wheel (and oh, I cringed a bit thinking of the lax safety standards that might make that possible. I’d probably find a different place to sit if that were me…).

And on it goes, another child finding it and using it as the seat of his imaginative adventures, but then there is a misadventure involving balloons and one thing leads to another.

You might be able to imagine what happen next. Somebody finds the chair, and it’s a grown man who’s name is Boo, and even though the chair has been painted he can see where the paint has chipped and he can tell that this little chair is familiar. And quite conveniently, Book has a little person of his own at home for whom the little chair is precisely the right size, and she declares it perfect.

February 9, 2017

Ada Lovelace: Poet of Science, by Diane Stanley and Jessie Hartland

Harriet and I went to see the remarkable Hidden Figures on the weekend, and until the picture book version of the story is released, we will content ourselves with Ada Lovelace, Poet of Science: The First Computer Programmer, by Diane Stanley, illustrated by Jessie Hartland, which was recently selected by the America Library Association among the top ten feminist picture books of last year. (We also know Ada Byron [later Lovelace] as a character from Canadian author Jordan Stratford’s middle-grade series, The Wollstonecraft Detective Agency.)

True confession: I don’t understand computer programming. It’s possible that a lifetime of being told that math is hard made me believe that math is hard, or maybe I just find math hard, but my mind doesn’t work that way. I’ve read Ada Lovelace: Poet of Science several times, and while I understand in theory how Ada imagined Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine worked based on symbols and rules of operation changed into digital form…I actually don’t even understand it in theory. Ada Lovelace’s ideas were inspired by mechanical looms which wove textiles based on patterns dictated by punched cards. I don’t really understand that either.

But but but. There is more than one way to be a person, to be a woman, to have a brain. That such things befuddle me is not to say that women are like that and let’s all go back to rocking babies, but instead to say that some women have an aptitude for such things, and it’s useful for even those of us who don’t to realize this. It’s like saying, Maybe I don’t need feminism, but some women do. (Nobody ever says this though. People who don’t need feminism seem to forget the possibility of second clauses.) To be honest, I’m not sure my daughter is going to grow up to be a computer programmer either, genes being what they are, but I will insist on the fact that she knows it’s a possibility. I mean, if a girl could have been one two hundred years ago, before there were even actual computers, then maybe today there are perhaps no limits of what a girl can grow up to be. And isn’t that excellent?

We love this book, about Ada (who gives Rosie Revere, Engineer a run for her money) who has a spectacular imagination, despite her mother’s attempts to school her in logic and rational thinking in order to override her passionate poet father’s genetic legacy. As women of her station had to do, she settled down and married, but that wasn’t the end of her story, and she would go on to do remarkable things in her too short life, indeed becoming the world’s first computer programmer with Babbage’s analytical machine. And what is especially interesting is that there is no direct link between Babbage’s and Lovelace’s work and the development of modern computers, although as Stanley’s author’s note points out, Alan Turing would read their work after they resurfaced after a century of obscurity. But still, I am fascinated by this idea (which is so recurrent in feminism) that some ideas have to be invented over and over again. Or perhaps it’s more miraculous than that—that the great discoveries don’t just happen once, and that progress ain’t a line, but that spectacular bursts of excellence are exploding all the time.

February 3, 2017

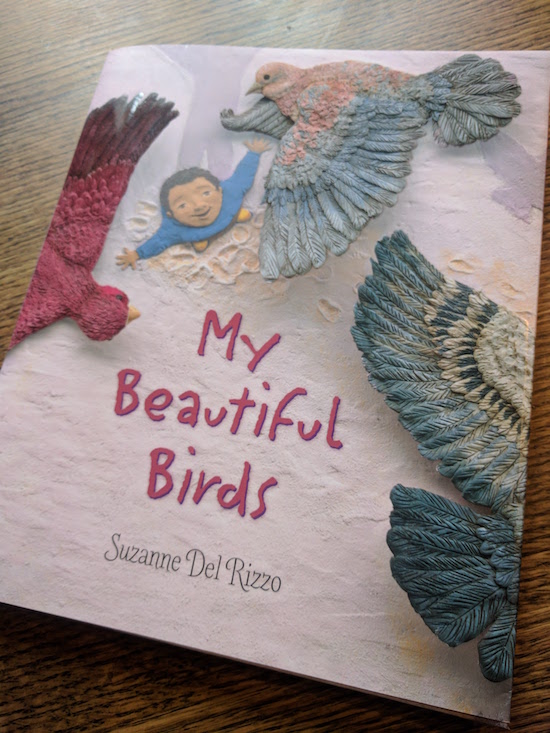

My Beautiful Birds, by Suzanne Del Rizzo

As weird and terrible as the world can be, I don’t spend a lot of time, as the modern problem goes, worrying about “how I’m going to explain it to my children.” As I’ve written before, I relish awkward conversations. But I was thinking about this idea yesterday, about how incongruous it must be to be both a parent and somebody who wants to see refugees restricted from finding sanctuary in their country and community. What do these people teach their children about helping others, I wonder. Do they ever worry about the gap between their messages?

“As a parent,” somebody told me on Twitter this week, “my job is to protect my children from danger.” Hence their support of UnpopularDonald’s Muslim Ban. And the logical next question, although I didn’t ask it because this was Twitter and there was really no point, is “Isn’t that precisely what so many refugee families are doing though? And so surely as a parent then, you can recognize the humanity in these people, that they are guided by the same impulses that direct you, except that their homes have been destroyed by years and years of war and your fear is based on a sense of otherness and is also statistically irrational?”

The first time I was happy after November 9 2016 was a few weeks later at the Canadian Children’s Book Awards, and not just because I’d had more than a few glasses of wine. But it was because of the spirit that night, the speeches of the presenters and winners that acknowledged the darkness of the moment we’re currently embroiled in and that books really were one sure way to kick at the darkness, children’s books in particular. Books that bridge the distance between here and there, between us and them, and recognize the humanity common to all of us.

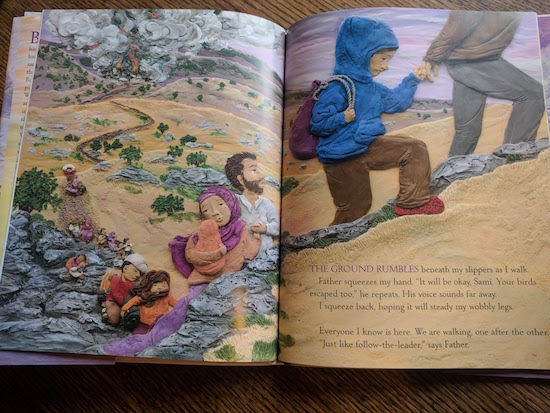

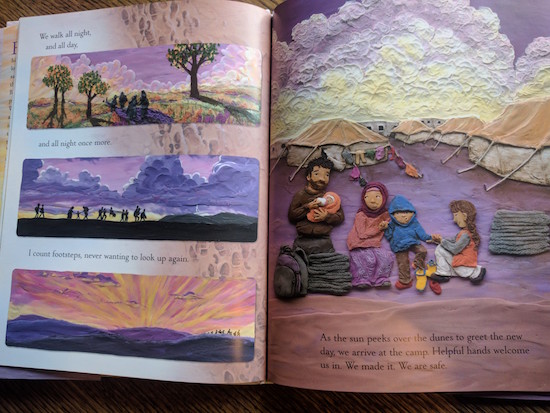

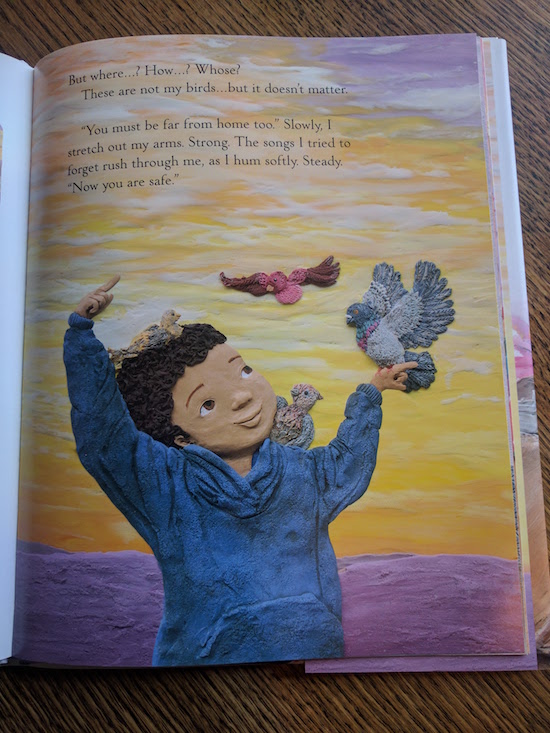

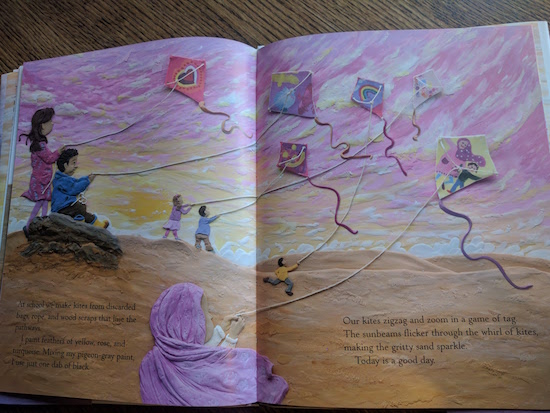

In Suzanne Del Rizzo’s picture book, My Beautiful Birds, a young Syrian boy is forced to leave his wartorn home and make the long journey to the relative safety of a refugee camp. The story is enlivened by Del Rizzo’s plasticine illustrations with their rich purple and golden hues. Of all the things that Sami has left behind. it’s his pigeons he misses the most, the birds he fed and kept and as pets. Although his family does their best to create a home in the camp—planting a garden, buying things in the small shops started by their neighbours—this new life is anything but sure: “Days blur together in a gritty haze. All I have left are questions. What will we do? How long will we be here?” The idea of the birds and their freedom symbolizing everything that’s been lost to Sami.

Del Rizzo shows Sami’s grief and sadness with thick black lines that overwhelm the pictures he tries to paint of his beloved birds, the black paint taking over his art like a storm. Where he finds solace, though, is in the sky, one thing that is familiar to him, “wait[ing] like a loyal friend for me to remember.” In the clouds, he sees the shapes of his birds: “Spiralling. Soaring. Sharing the sky.”

January 27, 2017

Picture Book Wisdom

It’s Family Literacy Day today, and I’ve written a post at 49thShelf about how everything I know about the world I’ve learned from picture books. Including, “Dance in the kitchen. Don’t do the dishes” and “Far more than any fame, enjoy the peaceful pursuit of knowledge. Treasure the wealth to be found in your books.”

You can read all the words of wisdom here, and make sure you pick up these great titles if you haven’t already.

January 20, 2017

Have You Seen My Trumpet?, by Michael Escoffier and Kris Di Giacomo

Tonight at dinner, Harriet told us a story. “Today for Show and Tell,” she said, “Eric brought in a diaper.” A diaper? “Yes,” she continued. “He punched it, and then he cut it in half and took these things out from inside it, and he put it in his jello bowl, only there wasn’t any jello in it.” I was trying to make sense of this. “So it was like an experiment?” I suggested. The insides of diapers are filled with these gross little gel balls that I only know about because of the times(s) I put a diaper through a wash cycle and it exploded (don’t ask).

“And then he ate it,” said Harriet, and I said, “What?” and we all started laughing, quite hysterically, the way you might if you were eating dinner, someone ate a diaper, and the world’s worst man was being elected the American president tomorrow.

At certain moments, absurdity is fitting, and not much else these days is making the me laugh the way I like to laugh, which is to say, so hard that I shake noiselessly with one of my eyes closed—trust me when I tell you it’s very attractive. At certain moments all you want is a picture book with a sea urchin, a gruff fly, a missing trumpet, and a bat that’s sitting on the toilet. In 2016, the word of the year was “surreal,” and so all this is quite in keeping with the zeitgeist.

Have You Seen My Trumpet?, by Michael Escoffier and Kris DiGiacomo, is a book that’s brought delight to all of us during the past few months. Ostensibly the story of a small girl searching for a trumpet (that doesn’t turn out to be quite what you’d expect), the book’s true charm is spread after spread of bizarre beach scenes with appealing illustration and engaging, amusing details. On every page, a question is asked whose answer is to be found in not only the illustration, but also the question itself—and don’t you love that smug fish (above), who’s hogging all the pails and is sporting his I Love Me t-shirt?

The strangeness of the English language is underlined by this exercise—because indeed, the crow thinks it’s too CROWded, but that’s not we say it. And while it’s true that the owl has fallen in the bOWL, we don’t pronounce “bowl” as “bowel.” Which brings us to everybody’s favourite page, who’s in the BAThroom indeed?

It’s almost as weird as a kid who brought a diaper to Show and Tell and ate it, and makes as much sense as anything.

January 6, 2017

Rad Women Worldwide

Quite intentionally, I am raising my children in a house full of books, and while this has resulted in my children engaging with books a lot, best intentions don’t always lead where you’d like them to. I do have a theory that books can work by osmosis and that just being around them makes people smarter, and I cling to this belief when my oldest child passes up the incredible works of world-broadening non-fiction we have stocking our shelves in order to reread the Amulet series for the five-hundredth time. I had this vision of children sprawled on the carpet, leafing through our encyclopedia of animals, illustrated atlases or perusing the images from Sebastian Salgado’s Genesis. Sometimes I even intentionally leave these books on the floor, so as to instigate said leafing and perusing, but then the children just end up using these books as stools on which to perch while reading Amulet.

The book Rad Women Worldwide, by Kate Schatz and illustrated by Mariam Klein Stahl, might have joined this pile of books for sitting on. It was an extra Christmas gift, purchased without forethought. A good book to have around the house, I thought, particularly in these regressive times. Subtitled, “Artists and Athletes, Pirates and Punks, and Other Revolutionaries Who Shaped History,” by the creators of the brilliantly conceived American Women A-Z. It doesn’t hurt that the book’s design is awesome. I loved the idea of my girls learning about the incredible women profiled within, and understanding that their amazing accomplishments are what history is made of. We don’t even have to call it “herstory.” All this is simply the society in which we live.

Rad Women Worldwide includes women making history throughout history, but also women who are making history as I write this. And I love the idea of my children taking for granted not just that history includes women, but that history (and feminism) includes women of colour also—this is huge if I hope to raise white feminists who aren’t White Feminists (TM). I want to raise girls who see race and know race, acknowledging the role it plays in people’s lives (including their own). And I want them to know that the world and progress is powered by women who are black and brown and Asian, as well as white. I want my white children to grow up inspired by the accomplishments of women of colour—and with this book, how can they not be?

The thing about Rad Women Worldwide, though, is that it’s not just for children. It’s not only they who have gaps in their education, and the stories in this book are so fascinating that we’ve started reading them aloud. So that this isn’t a book just for sitting on, but also because I want to learn more about the women I’ve already heard of (Aung San Suu Kyi, Malala Yousafzai) and want to discover those I hadn’t heard of yet (Kalpana Chawla, the first Indian female astronaut, Junko Tabei, who was the first woman to climb Mount Everest, Fe Del Mundo from the Philippines who was the first woman admitted to the Harvard Medical School in 1936).

So we read a profile a day, Harriet and us taking alternate paragraphs, and I love the words that are entering her reading vocab: “Indigenous,” “Constitution,” “Advocacy,” “Reconciliation.” These stories are the perfect antidote to the bleakness that pervades news stories about women right now, riding the sad coattails of #ImWithHer. Inspiring, fascinating and ever-illuminating, each story affirms my faith in progress and justice just a little bit more.

December 15, 2016

Christmas Books

We’re winding down to the holidays (although, unfathomably, they don’t start until the end of next week when school’s out). Instead of Picture Book Friday, I want to point you toward my Instagram account where I’m sharing a title from our Christmas Book Box every day. We’re also reading the short novel A Christmas Card now, which our friend Sarah read last year (as we were reading The London Snow, by the same author, Paul Theroux). Today we walked home from school in a glorious blizzard, and hot chocolate with marshmallows are getting to be a habit.

December 2, 2016

The Day Santa Stopped Believing in Harold

I full-on believed in Santa Claus until I was eleven, mostly through sheer force of will and because I was a strange child, and I’ve actually kind of still believed in him ever since then. If asked if there is a Santa, I’ll never say one way or another, because there are some kinds of magic that are beyond our understanding. If asked if I in fact partake in performing the duties of Santa, I may concede that I do, but that such partaking is in fact part of the magic, but no one’s asked me that question yet. There have been other question though, and I will answer them carefully, recalling my own longing to believe that so preoccupied me as a child, a longing that had me actually making notes on the books I was reading and tallying those in which Santa was confirmed as real or otherwise within said books (and there became more of the latter, obviously, as I became actually eleven—I think I was actually reading Sidney Sheldon novels when I was eleven, although Santa rarely came up in these).

The Day Santa Stopped Believing in Harold, by Maureen Fergus (Buddy and Earl) and Cale Atkinson (If I Had a Gryphon) is definitely pro-Santa, and the perfect book contending with these sorts of questions who’s just not quite ready to give up yet. Santa, it seems, has stopped believing in a child called Harold, because the letters Harold writes to Santa are penned by Harold’s mother and Santa’s snack each Christmas Eve is actually catered by Harold’s father. Santa’s wife tries to convince him otherwise, but Santa will not be deterred, and resolves to wait up until Christmas morning so he can see Harold for himself and finally discover whether or not he actually exists…

I bought this one to commemorate the beginning of the Christmas season, a new title for our Christmas book box, and we absolutely loved it. It’s sweet, silly, and the perfect Christmas book for the savvy kid who wants to go on believing just a little bit longer.

November 25, 2016

How Do You Feel?

I’m going to say it—it’s been a rough few weeks. Yesterday I asked a parent in the school yard if he was American, intending to wish him a Happy Thanksgiving, and he looked so upset when I asked him. “I’m not accusing you of anything,” I said. “I’m just trying to create some distance from that mess,” he responded, and I got that. I’ve been trying to create some distance too. I took Twitter off my phone. Between conspiracy theories, white supremacy and CanLit ridiculousity, the platform has ceased to have much value except for to constantly have me exclaiming, “What that actual fuck?” I’ve tried telling men’s rights activists to eat various bags of dicks, and attempted to engage with a woman who insisted that the patriarchy wasn’t real (“That’s what they want you to think,” I told her, with a winky face, which she didn’t think was very funny, and my goodness, I thought feminists were the humourless ones) and watching what’s happening at Standing Rock just causes me to despair.

There are a whole lot of people on Twitter who, before November 8, I’d been in adamant disbelief that they were actually real. But it seems that they exist, human bots. Who refuse to read anything but Wikileaks emails, have eggs instead of heads (remember when once upon a time that implied intelligence?) and have no passion for anything except the things they hate. Which is anything the least bit challenging. And there is this atmosphere of disdain for feelings. Slinging “crybaby” like an epithet. This from people supporting a man whose supporters had been stockpiling arms for the event of their disappointment—and suddenly crying was something terrible? Speaking of alternate universes.

Who are they, the people who make fun of feelings. Do they not understand that it’s feelings that underline the dangerous fabric of nationalism? That there is nothing rational about screaming nonsensically at a rally, or screaming, “Kill the Bitch? (I am never going to forget that phrase.) That the notion of safety has become a joke. Why would denying others such a thing be the hill you’d choose to die on? And I keep getting emotional—of course I do. I feel terrible. I am sad, and angry, and frustrated, and disappointed. And really, really confused by the determination of others to put our precious, fragile, precarious arrangement in peril.

Pendulums swing though. And back. It’s the way of history. And it’s healthy to keep asking ourselves questions. “How do we keep what we believe in and know it’s right from becoming dogma?” I asked my friend May yesterday, and that’s a whole other blog post. We talked about how apparent injustices are now, all those things we were able to ignore before that have risen to the surface. To be acknowledged, looked in the face. Finally. It’s all very hard, but necessary. And in the meantime, the question of feelings are going to be more so. (See also this post: What are you going through?)

On Thursday I went to the Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards Gala, and drank all the wine, which helped a bit with the whole feelings thing. And in my silly bubble of happy, I felt grateful to be surrounded by people who acknowledged the power of books and of story and truth and history. We need books more than we’ve ever needed them, books to keep us asking questions, books to make sense of the madness, and to underline to our children the things that are important and ever shall be.

Harriet remains a hedgehog fanatic, and therefore we have all become fond of the book, How Do You Feel?, by Rebecca Bender. I love the double meaning of the question (because anything that teaches that a single thing can have two realities is important), and that the answers to the questions are all about words and similes. The whole book is about connection, and it’s sweet and lovely, and also powerfully subversive in the most important way.

November 18, 2016

Missing Nimama

Congratulations to Melanie Florence and Francois Thisdale, whose hauntingly beautiful picture book, Missing Nimama, about a murdered Indigenous woman won the TD Children’s Book Prize last night at The Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards. This book is an extraordinary demonstration of what the picture book can be and do; you can read my review here. I’m also thrilled for Danielle Daniel who won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Prize for Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, another book we’re big fans of at our house.

A complete list of winners is here. It was a terrific night.