May 26, 2017

The Gold Leaf, by Kirsten Hall and Matthew Forsythe

The Gold Leaf is the kind of book that you’d think at first glance was by an author/illustrator, a conceptual book in which the images are fundamental. Beautiful, lush, classical styled illustrations of a forest turning into spring.

But then the words too, all the ways to describe greenness. “Jungle green, laurel green, moss green, mint green, pine green, avocado green…” I love any book that emphasizes the many different ways there are to be one thing. I also love how in this case, the splendid text is enriching the picture.

Anyway, the animals are awakening from winter slumbers and in all the newness and excitement, everyone almost misses the sight of something most unusual:

An author’s note explains the process and history of gold leaf as an art form, as well as the the author’s grandfather was responsible for the gold leafing on many famous buildings in New York City, adding another layer of texture to this beautiful story.

Well, obviously the gold leaf is coveted amongst the forest creatures, and one after another they snatch it, keep it, grab it and run, and the inevitable occurs—the leaf falls to pieces, scattered in the wind. And then life in the forest goes on as it should—until the following spring (with “pear green, pickle green, parakeet green…”) when the gift returns to them. A story about second chances, gifts and mercy, maybe, and community, precious resources, and how much richer we are when we take care of each other.

The book, in its exceptional design and quiet story, reminds me of Coralie Bickford-Smith’s The Fox and the Star, which we loved, and also a little bit of Kyo Maclean’s beautiful new book, The Fog, with its subtle environmental message and open-endedness (and also a warbler). And yet its utterly itself as well, and we absolutely love it.

May 19, 2017

The Way Home in the Night, by Akiko Miyakoshi

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that everyone has their own story, about light in the dark, and pie, baths and bookshops. (The final clause of that sentence is evergreen, but still.) The Way Home in the Night, by Akiko Miyakoshi, brings all of these ideas together in a quiet thoughtful way and manages to be a lullaby—for the whole wide world.

(Check out the endpapers:)

Miyakoshi’s third book in English (after The Tea Party in the Woods and The Storm), The Way Home… is about a child (rabbit?) coming home when its late, sleepy in her mother’s arms. They walk together in the darkness of the city, past stores closing up shop, through empty streets which are illuminated by streetlights and the lights from people’s windows.

The child hears vague sounds, smells different scents in the air, and ponders what these tell us about what’s going onside the lives of the people at home in all the houses.

And I love that—curiosity about the lives of others, an acknowledgement that everybody is a character in their own story, stories we only sometimes get a glimpse of. That each of us is not the only person in the world, even, and that when we sleep—settling down to the bed as the narrator does after her mother tucks her in—the world is still going on without us, people going places, other people coming home.

The book then turns into an exercise in storytelling as the rabbit drifts into sleep, imagining the characters she encountered on her journey making their own way home, drawing a bath, settling down with a book. What can we know about other people, the book is asking us. And what does it mean when we bother to try? The point being that this wondering is what connects all, each of us with our own lit windows, our self-contained universes. In fact, we’re all a constellation.

May 4, 2017

A Bird Chronicle, by Ruth Ann Pearce & Rina Barone

I’ve been following Curiosity House Books on social media for awhile now, so when I finally got to visit Creemore on Saturday, a highlight was getting to see the picture book created by their in-house publishing company in real life. A Bird Chronicle is an ABC book, a bird book, and an art book. It’s even a font book—every letter and bird has its own typeface, i.e. H is for “Half-collared Kingfisher” and also for “Hoefler“; O is for “Ostrich” and “Optima.” Most of these are birds I’ve never heard of before (“i’iwi,” anybody? Or turquoise-browed motmot?) and each one is given a name (alphabetically, of course, i.e. the American Kestrel is called Andy) and a little alliterative verse that tells us something about the bird’s habits or habitat. It’s all a little bit abstract, but fun to read—try saying, “Oh how she wishes the fishes would just hurry up…” and not feel good. Each bird had a vivid colour illustration, accompanied by a very cool silhouette, and the whole thing is lovely. I would have bought it—even if H and I had not turned out to be particularly close to home… It’s a gorgeous, singular and enjoyable book, and everyone at our house has fallen in love with it.

April 21, 2017

Stop Feedin’ the Boids, by James Sage and Pierre Pratt

There are several levels in our appreciation of Stop Feedin’ Da Boids, the new picture book by James Sage and triple Governor-General’s Award Winner Pierre Pratt.

Number One: the whole wildlife in the city thing. I was a fan of Alissa York’s Fauna a few years back, and this story similarly illuminates the wildness hiding in the concrete jungle—and not just the people and their dogs either. Pratt’s beautiful spreads bring the diverse and frenetic city to life, and this is a city in particular: Brooklyn, to which Swanda has moved after years in the countryside, leaving rolling hills and animals grazing in pastures behind,

Number two: the pigeons. This has been a season for birds, literary-wise, but pigeons still don’t get a lot of respect. The great thing about wandering the city with children, however, is that they don’t discriminate, and pigeons and sparrows are as marvellous as downy headed woodpeckers. In fact, imagine seeing a pigeon for the first time in your life. Wouldn’t you think it beautiful? So I can kind of understand their appeal, why the animal-loving Swanda jumps on the pigeon-feeding train…but things quickly spiral out of control and soon the neighbourhood is overwhelmed in that particular way only pigeons can make an urban place.

Which brings me to the third level of our book appreciation, the splendid moment in the text when, after reading the scrams and the shoos and the subtle suggestions by neighbours and experts (“I’m afraid the problem with pigeons was ever thus…”, when finally, finally, push comes to shove, and the reader gets to proclaim with the entire city street:

It’s intoxicating, that proclamation. And now my three-year-old has taken to calling birds “boids,” and it’s catching. And now we kind of want to move to an apartment in Brooklyn with big old windows, fire escapes and a superintendent called Mr. Kaminski… By this point, however, Swanda has started feedin’ the fish, and you’re going to have to read the book to learn how that turns out.

April 14, 2017

The Fog, by Kyo Maclear and Kenard Pak

Sometimes it is useful to be reminded that not everything is an allegory. But at the same time, those “It doesn’t have to mean anything! It’s a story!” people are even more annoying, because a story has to mean something, or else what is the point? Which isn’t to say that every book should necessarily be Animal Farm. The answer, as with most things, is somewhere in between, and in her latest picture book, The Fog (illustrated by Kenard Pak), Kyo Maclear has achieved that balance with stunning precision.

Maclear’s early picture books had obvious messages—Spork was about being mixed-race, Virginia Wolf was about loving someone with depression, Mr. Flux about learning not to fear change. They were good books and artful, but Maclear’s more recent work has become less concrete, more nuanced. While I’m entirely in love with her book Julia, Child, however, I admit I’ve never been able to get my head properly around it; it’s a book a little too intent on trying to mean. Her others like The Specific Ocean, however, manage to mean without trying to. And her latest, The Fog, is her best work yet.

It’s a book about a bird who likes to people-watch (and this book ties in nicely with Maclear’s recent memoir, Birds Art Life). The endpapers are illustrated with human varieties—”Dapper Bespectacled Booklover,” “Masked Bohemian Weaver,” “Solitary Knitter.” The bird is named Warble and he lives in a place called Icy Land, an island that people from all over the world come to visit, giving Warble excellent opportunities for spotting. One day, however, a thick fog descends, and everything changes. It’s hard to see, the people stop coming, but nobody seems to notice. Nobody, however, except for Warble.

The birds around him adapt—this is what living creatures do. Soon, nobody else remembered that there hadn’t always been fog, and even Warble began to wonder if things had ever been different.

But one morning something happens. Peering through his bins (I say “bins” instead of binoculars because I’ve just finished Steve Burrows’ latest Birder Murder Mystery and I know the lingo…) Warble spots a speck on the horizon: “Peering closely, he saw a dark-haired human ghosting through the meadow. It was a rare female species and she was singing a song.”

The usual transpires: he offers her insects, she teaches him origami, and then they both acknowledge the fog. And they wonder—if each of them can see it, might somebody else out there be able to see it too? So they send out paper boats with the message, “Do you see the fog?” and after a long, long wait some answers return. “Notes arrived from around the world: “We can help!” “We see it too!” And with every message received, the fog lifted a bit, until you could see things again. “Big things. And tiny things. Shiny red things. And soft feathery things.” The story ending with Warble and the girl together against the starry sky enjoying the clear night view.

So what is the fog then? Is it climate change denial? Is it fascism? Is it the volcanic ash that enveloped Iceland in a cloud not too long ago, grounding flights around the world? None of these suggestions mapping onto the book exactly, but in this they serve to open up the story and the ideas it offers rather than rendering them in a narrower fashion. What does it mean? becoming the beginning of a conversation.

April 7, 2017

A Horse Named Steve, by Kelly Collier

Is there room in Canadian literature for another equine creature who’s got a couple of quirks? Which is to say, if you have a thing for roly-poly ponies, do you actually need a horse named Steve?

But you do! Because it turns out that A Horse Named Steve is a genus all onto itself.

The debut picture book by Kelly Collier, A Horse Name Steve (published by KidsCan Press, which just won North American Publisher of the Year at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair) is a fun, comics-inspired tale of an ordinary horse who wants to be exceptional. When he finds a gold horn lying around (as you do) he imagines an exceptional life lies before him now, but then when he gallops off to show the golden horn to his friends, things go ever so slightly…askew.

With the horn out of place, Steve’s colleague, Bob the Racoon, reports to him, “I don’t see a beautiful gold horn on your head. You are not exceptional.” Which comes as a shock, and poor Steve cries so hard he gets thirsty, and when he goes to get a drink, our little pseudo-Narcissist sees in his reflection that the gold horn is right there after all. It’s no use though, because horses are not so dextrous in this respect, and when he goes to fix his horn, Steve ends up falling in the water. “Poor Steve. He is hornless and drenched.”

The tragedy that has befallen him has a positive outcome though—turns out that Steve’s horn has started a thing-on-the-head mania amongst the forest creatures, and when he falls in the water and his horn gets lost…suddenly Steve is exceptional again. Turns out bare heads are where it’s at after all—”I love the natural look he’s got going,” says the rabbit, the other animals agreeing, “Very stylish. How does he do it?”

Surely there are lessons contained within about the importance of accepting one’s self, being an individual, blazing a path instead of following a path, etc. But the great charm of this book is that these ideas exist deep in the background while A Horse Named Steve manages to be exceptional in its own right—the simple drawings, the humour, the chatty asides that make reading the book aloud an absolute delight.

March 31, 2017

The Everywhere Bear, by Julia Donaldson and Rebecca Cobb

My favourite Julia Donaldson is Julia Donaldson with Rebecca Cobb in The Paperdolls (even if I do have to add in that the little girl in the book grew up to become a particle physicist, a politician and an opera singer, as well as “a mother,” because let’s remind our children that a person can be very well rounded), so I was delighted to see their latest collaboration, The Everywhere Bear. Ticky and Tacky and Jackie the Backie don’t make an appearance, but we’ve got Ollie and Holly and Josie and Jay, Leo and Theo and April and May, etc. etc. All members of a classroom whose class bear comes along with the children on various adventures, but then one weekend things go amiss the bear gets lost, embarking on a remarkable journey of his home that will bring him home again. “Hooray! Hooray!” cheer my children at the end of books like these. “Nobody dies!” They will not tolerate an unhappy ending—even the paper dolls’ snipped up fate makes them a bit uneasy, but we all love this one, Donaldson’s bouncy rhyme and Cobb’s adorable round faces. A keeper for sure.

March 24, 2017

Town is by the Sea, by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith

Never has a book so literally sparkled like Town is by the Sea, a new collaboration by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith. In the story, Schwartz draws on her own Cape Breton background to tell the story of a day in the life of a coal mining town, about the life that goes on up above while the men are working down below.

And in a book about contrasts, illustrator Smith pulls off a similar feat. As his early books (reissues of Sheree Fitch’s classics are where we first saw his work!) were fun and cartoonish, that same sensibility charges many of the images in this book—illustrations of domestic life and children at play. (He also exhibits a fixation on teacups that won this book a firm place in my heart.) But the teacups aren’t all of it—just wait for a moment.

Because first we see the men going down into the mines to work. (My children are fascinated by this. “What is coal?” Iris asks us, which is weird because usually she manages to parse out meanings, is rarely moved to ask about something so explicitly.)

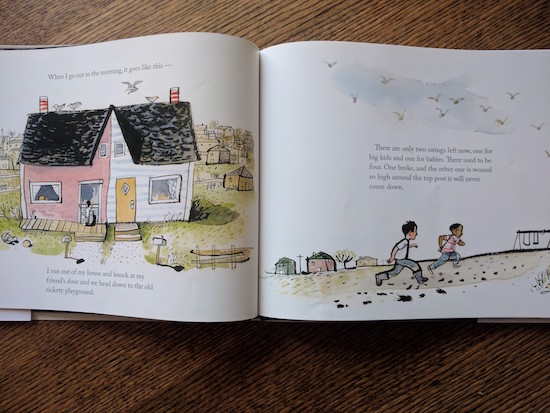

“When I wake up, it goes like this—” Schwartz’s story starts, and this pattern sets up the way that the boy in the book will tell his story. First he hears seagulls, and then a dog barks. “And along the road, lupines and Queen Anne’s lace rustle in the wind…”

“And deep down under that sea, my father is digging for coal.”

And now here it is, that sea. A sea so sparkling that it appears animated, an image that would not look out of place in a museum. Hasn’t it got a bit of the Monet about it? Otherworldly. Which is fitting.

Meanwhile, the boy plays with his friends, he walks through town. He goes home for lunch, then goes back out again. The sea is perpetually present, and its evocation brings us back to the men in the mines. “And deep down under that sea, my father is digging for coal,” and my children read along with the refrain. But the last time we see the men, something is different.

The text doesn’t allude to the image of the men escaping some kind of collapse underground, and the sing-song story goes along, but what happens next in the illustrations takes on a particular subtext, a wordless story like the one Smith tells in JonArno Lawson’s award-winning Sidewalk Flowers*. The boy goes to visit his grandfather’s gravestone, his grandfather who was a miner just like his father, and who made sure that he’d be buried facing the sea because he’d spent enough time underground. “I go to the graveyard to visit my grandfather, my father’s father. He was a miner too. The air smells like salt. I can taste it on my tongue.”

The trouble underground and the imagery of death will make for some uneasy for reading for those of us who know the dangers of coal mining, who’ve heard the stories of disasters. But alas, that is a story for another day. In this book, the boy’s father comes home. Danger and peril, and it’s still just an ordinary day.

“One day it will be my turn,” the boy tells us, about the men who go down below to mine for coal. “I’m a miner’s son. In my town, that’s the way it goes.”

*Full credit goes to my husband Stuart who is much better at reading picture books than I am. It took me ages to figure out that the bear had eaten the rabbit in I Want My Hat Back, or what was different at the end of Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. I might have read this book a hundred more times without realize the enormity of what’s really going on beneath the surface (see what I did there?) so I am glad that I keep someone very clever around.

March 17, 2017

You Are Three, by Sara O’Leary and Karen Klassen

Three is a good age, is a thing that someone said to me today, and it might have been the first time I ever heard that. I cocked my head. “Oh, really?” Although she was talking about her grandchild and maybe three is a good age if the child is only yours on a partial basis. For the rest of us though, three is a battle. Three is ferocious, still wakes you up at night and no longer naps. Three has more complex needs, and will still bite you in a pinch. Three is strong and tenacious and refuses to give in, and can whine and whine until the sun goes down. And keep on whining.

And yet. Three is also sturdy legs that can walk long distances with no complaints. Yes, three will point to your stomach and remind you that you look like you’re having a baby, but three will also whisper in your ear that you look like a princess. You never even knew you desired to look like a princess, but you are satisfied. Three tells stories about her friends at school, and eats everything in her lunchbox even though she never eats at home. She loves cats, but only if they are pink. Three likes to read chapter books because her big sister reads chapter books, and she picks sparkly ones out at the library with fairies on the cover, and she sits alone thumbing the pictureless pages and you wonder what she sees.

So yes, three has been a good year, even though three is hard and stubborn and still screams when you are unable to conjure impossible things. Three will howl for blocks and blocks or run away from you in a crowded subway station just to demonstrate how much she doesn’t want to hold your hand. But three will also sit at the table, most of the time. She will tell jokes and contribute to discussions and ask questions and point out things you never would have noticed on your own. With a three-year-old, you are a family, instead of three people and a baby. Your seven-year-old will say to you, “It’s really great to have a sister you can talk to.” And you will only be partially totally confused about what exactly she means.

(My favourite thing in the world is listening to my three-year-old singing along to songs that my seven-year-old is making up on the spot.)

Three is a good age, because it means we no longer have a baby. We never wanted another another baby after we had our last one, and I don’t lament the end of the baby years. My baby is heading off to kindergarten in the fall and I am fine with that. This is why we had babies anyway; the babies were what we had to go through to get the kids. And we love the kids. We toss the baby stuff out to the curb and cheer, and have filled all that space with camping equipment.

And so I was surprised to be moved by You Are Three, the final book in Sara O’Leary and Karen Klaassen’s trilogy celebrating the milestones of toddlerhood. Flipping through the pages the other night, I felt a bit emotional. Because three is a cusp, about to unfurl. Three is a person’s threshold to the world, and while I’m ready to usher my little person through the door, it’s easy to forget the moment we’re in. This funny girl will never again be so funny, or at least not funny in the same way. The You Are Three book reminds us to notice where we are right now: the kid who rides a scooter, carries her umbrella, and loves to hide. Her incredible worlds of make-believe, and her pictures, and the ways she sings her ABCs. “You are still our baby/ but you are also your own person./ We love to hold you close/ and we love to watch you run.”

March 10, 2017

Under the Umbrella, by Catherine Buquet and Marion Arbona

A beautifully illustrated picture book that celebrates a few of my favourite things, namely light, umbrellas, and baked goods? Yes, please.

This week’s pick is Under the Umbrella, by Catherine Buquet and Governor General’s Award-winning illustrator Marion Arbona, translated by Erin Woods. As we turn towards the season in which the rain can seem unceasing and the world still a bit too cold and grim, it becomes important to be reminded not to hurry too much, and not to miss those moments in which light and communion is possible.

The book begins with a man who’s doing battle with the wind and rain, barrelling his way along his journey, and furious at the crowds and the weather, and everything that’s offering resistance. We follow along with him in rhyming verse: “The wind attacked. He bent his back/ and forced his way along./ Wet and cold and late—what else/ could possibly go wrong?”

The man doesn’t even notice the boy he passes staring into the window of the bakeshop. “Dry beneath the awning,/ he gazed upon the spreads/ Of cakes and creams and cookies/ meant to turn each passing head.” And what follows is a delicious golden spread that’s entrancing, a torrent of dancing baked goods…

When a gust of wind rips the umbrella away from the hurrying man’s clutches, the flyaway object lands at the little boy’s feet. The boy retrieves it and the man offers his thanks, and suddenly notices the world around him, the light at the window, the good things on display inside. “Aren’t they amazing?” the boy asks him.

I’m going to spoil the ending: the man goes inside and buys the wide-eyed boy a rhubarb-raspberry tart. (Like most things with rhubarb, I assume it’s made palatable with a great deal of sugar: yum.) And when the man delivers this delicious treat, the boy breaks it in half and shares it. Possibly he knows that shared baked goods have no calories…

“Under the umbrella, time seemed to stall. The rain fell on…/ The sky hung low…/The crowds crept by…/ And none of that mattered at all.”