March 29, 2018

The Triumphant Tale of the House Sparrow, by Jan Thornhill

My husband got a new camera, and has been snapping photos all over town, including one shot of a ubiquity of sparrows in a tree, hopping from branch to branch and singing their song. He’d taken the photo after we all encountered the sparrows on our way to the library, pausing to watch them sparrowing. The sparrows were fascinating, and later as we looked at the photo we started talking about sparrows, how they were an invasive species, and I’d read once that that campaigns had used their domesticity (‘house’ sparrow) to have them further reviled—so it’s a gender issue, naturally. And then I realized that here was the segue I’d been waiting for.

“We have a book about sparrows, you know,” I said. A book that is absolutely gorgeous, Jan Thornhill’s The Triumphant Tale of the House Sparrow, which follows up on her award-winning The Tragic Tale of the Great Auk. I’d been intrigued by the sparrow book, but wasn’t sure what to do with it—it’s too long for bedtime reading, but looks like a picture book, so my biology-obsessed reader might not be inclined to pick it up on her own. So this was a perfect opportunity, and I started reading it out loud over dinner, and all of us were absolutely riveted.

Honestly, I’m not going to tell you everything, because I don’t want to deprive you of the experience we had again and again in this book, of beginning a new paragraph only to have our minds blown. We learned how sparrow species date back to prehistoric times and how populations of sparrows grew and changed their habits when humans discovered agriculture and started harvested the sparrow’s favourite food, which was grain. And now humans and sparrows have been living side-by-side ever since.

Sparrow populations spread as human populations did, house sparrows displaying their signature adaptability. But, Thornhill writes, “We humans have never been very good at sharing the food we grow with other animals—unless those animals are pets or livestock. The ones that eat our crops, we consider pests…and we always have.”

The remains of sparrows have been found in the stomachs of mummified falcons from ancient Egypt, and ancient Egyptians used a hieroglyph of a house sparrow to describe something as bad or evil. House sparrows would stow away on ships carrying the Roman legion. They grew so numerous that “sparrow catcher” became a legitimate occupation and sparrow bounties were demanded—although their meat was spare. “In fact, one old recipe for a simple sparrow pie calls for the meat from at least five dozen birds!”

But the house sparrow is not just detested. Thornhill underlining our own experience with the following paragraph: “[The house sparrow] can be fun to watch, particularly since it will go about its business—eating, preening, dust bathing, feeding its young—much closer to humans than other wild birds.” (We have spent hours over the years stopped at a house around the corner with a feeder in front watching the sparrows do what sparrows do. It never ever gets old…)

Sparrows were brought to North America and soon spread across the country, even hitching rides on boxcars with livestock and sharing their dinner. There were sparrow crackdowns even here eventually, though sparrow populations would soonafter decline for a different reason relating to the advent of automobiles, which was our favourite fact of the book (and such a neat lesson in unexpected consequences…). In 1958, Chairman Mao declared war on the Eurasian Tree Sparrow, which he saw as depriving food from Chinese people…and the decimated sparrow population that resulted would lead to a plague of insects, crop devastation, and a famine in which thirty million people starved to death.

The history of the house sparrow would turn out to be the history of everything, but the future of the house sparrow is also important. In some regions, sparrow populations having been declining for reasons scientists don’t understand, and while Thornhill is not an alarmist, she speculates that this reason might be important, and that the status of any species so connected with our own probably matters a lot. Because everything is actually connected, which is the very point of this wonderful, fascinating book.

March 16, 2018

March Break Special: The Big Bed, by Bunmi Laditan

A weird thing is March Break just a week after a week-long vacation, which makes it seem like those few days of school were a blip and we’ve been on vacation forever. And I am the luckiest because I work from home and therefore March Break gets to be a real thing here (except I am also the unluckiest, because it means I have to cram my workday into a couple of hours every morning while my children watch television; come next week I’ll have catching up to do). We didn’t have elaborate plans for the week, but they’ve come together nicely, and we’ve been up to fun things and enjoying evenings without the rush of getting to various activities and also no making lunches. And so to celebrate this free-and-easy week of goodness, I’m making this week’s Picture Book Friday selection a book that my children absolutely adore, a real crowd-pleaser, a book my littlest calls “the pee-pee book,” which is The Big Bed, by Bunmi Laditan, illustrated by Tom Knight.

You probably already know Laditan as the writer behind the very funny Honest Toddler blog and book, and she brings the same approach and humour to her first picture book. It’s written in the voice of a young child who is very persuasive and attempting to explain to her father just why she deserves his spot in the big bed with Mommy. “When day turns to night, it’s normal for people to seek comfort. No one can deny that Mommy is full of cozies and smells like fresh bread. Who wouldn’t want to cuddle with her?” Making good points too: “Quick question: Am I mistaken, or don’t you already have a mommy? Perhaps Grandma is available to sing you to sleep three or four nights a week.” And yes, maybe the narrator does tend to leave the bed a little, um, damp in the morning—but she’s got good three reasons why this is actually a positive thing (even if they are a little yuck). She’s even got a plan, in the form of a camping cot. She’s even going to let her daddy pick out some special new sheets for his “awesome sleeping rectangle.”

It’s a story that resonates for all of us, mostly because there was an extra body or two in our bed for years and I do indeed remember the struggles. Though to those of you still in the midst of sleep struggles or bed woes, maybe hold off on this book for just a little while longer. You wouldn’t want your little bed sharer getting any more ideas….

March 9, 2018

Sugar and Snails, by Sarah Tsiang and Sonja Wimmer

A thing that has surprised me lately is how much so many people seem to have invested in archaic systems I wouldn’t have thought give us much to cheer for, systems like colonialism, white supremacy, and the patriarchy. It’s a thing I’ve only been able to be surprised by, really, because I’ve gone about for 38 years in the world with white skin, an able body, financial stability, among other advantages I’m lucky enough to take for granted, which means there is a whole lot of living that I’ve never seen. Although I’m still a bit nostalgic for a few years ago though when I thought there were just a handful of stupid people who talked about things like “reverse racism,” and we just laughed at them—but now there are hordes who get outraged because a fruit stand puts up a sign that says “Resist White Supremacy.” A UK department store decides not to label children’s clothing by gender, and people go bananas. Which means that this is a particular cultural moment to publish a book critiquing what little boys and girls are made of (“frogs and snails and puppy dogs tails,” and “sugar and spice, and all things nice”), I think. I’m anticipating a backlash to Sarah Tsiang’s new picture book—Sugar and Snails, illustrated by Sonja Wimmer—that involves furious anti-PC women shoving puppy dog tails down their poor sons’ throats.

I’m anticipating the backlash because a) obviously, I’m kidding b) people are stupid and c) what Tsiang sets out to do in her story, she accomplishes so well, Wimmer’s images underpinning the whole project with a foundation of pure magic. (Sarah Tsiang is also author of the amazing picture book, A Flock of Shoes, among others, and magic is kind of her forte.) The book’s first image is a tapestry upon which the traditional rhyme has been cross-stitched, and then we see an older man with a boy and a girl, presumably his grandchildren, and the grandchildren are having none of that gender binary nonsense—the side-eye from the girl when she’s accused of being made of sugar and spice is pretty epic. And her brother wants to know, “What about sweet boys like me?”

But their grandfather is struggling to remember how it goes—”Pirate and dogs and noisy bullfrogs”? Are girls made of “Snails and rocks and butterfly socks?” And suddenly they’re all making it up together, a world where boys are made of “lightning, and newts and rubber rain boots” and girls are made of “boats and whales and dinosaur tales.” Wimmer’s illustrations literalizing the nonsense rhymes so that we see the kitchen filled with water as the boy wades in his rain boots and his sister swims as a whale (and everywhere there are teacups and teapots, which means this whole book is so up my alley I feel like I live within its pages…) There is also a reference to chicken butts, which means the children are totally on board, although they were pretty enthused in the first place. And never before has the patriarchy been bashed with such whimsy and a spirit of fun.

The book concludes with the tapestry image from the first page, but the children have pulled out many of the threads. Which means the work is still half-done, of course. Sugar and Snails inspires us to keep on imagining new possibilities for what boys and girls can be.

February 9, 2018

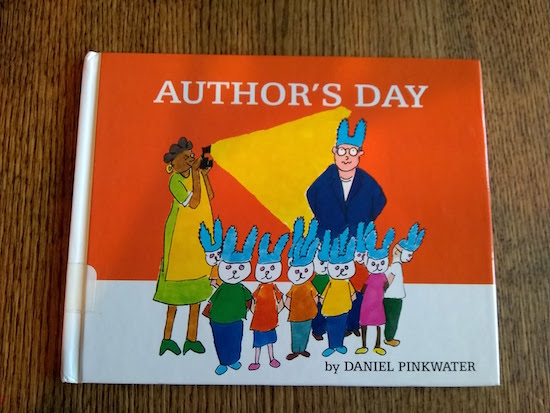

Author’s Day, by Daniel Pinkwater

Being an author always seems like it might be a little bit glamorous, which I know because I spent a large part of my life wanting to be one. Back in the days before I knew that your favourite author “spending an afternoon signing” at a big box bookstore really means she’s sitting lonely at a table, trying to coerce strangers into purchasing her book via fledgling sales and marketing techniques, unless she was JK Rowling, which she usually wasn’t. I have never spent an afternoon signing books at Indigo, mostly because I do not overestimate my own popularity and also I read that essay years ago by Margaret Atwood about signing her book in the socks department at Eatons. My first experience of encountering my novel in a bookstore only underlined to me that being an author is an exercise in mild humiliation. I’m still pretty raw about the reading I did in 2014 that nobody came to. Although I felt better after I did an event with a wildly successful author not long ago who gave me a dirty look when I suggested that all her events were well-attended—maybe the problem wasn’t just me. And also after I read Billie Livingston’s beautiful essay about a US book tour event gone wrong that ended up going oh so right. About “the spark that connects far-flung strangers,” which is why we write at all really, and the great privilege of putting a book into the world.

I don’t know if I ever thought that being a children’s author might be a less humiliating experience than publishing novels for adults, but Daniel Pinkwater’s book Author’s Day suggests that it isn’t. I also don’t really know how Pinkwater managed to publish Author’s Day, unless maybe he’d given some publishing executive’s toddler the Heimlich Maneuver and the book was payback for the favour. Because, from a child’s eye view, Author’s Day is not particularly appealing. It’s a picture book with two-page text-only spreads. The story itself is passive-aggressive as all get-out, angry, mean and completely self-serving—and I love it. My children find it weird and a little bit funny, but I think it’s brilliant. I found it in the library about a year ago, and then absolutely had to have a copy of my own, which I was able to purchase on Amazon for a penny.

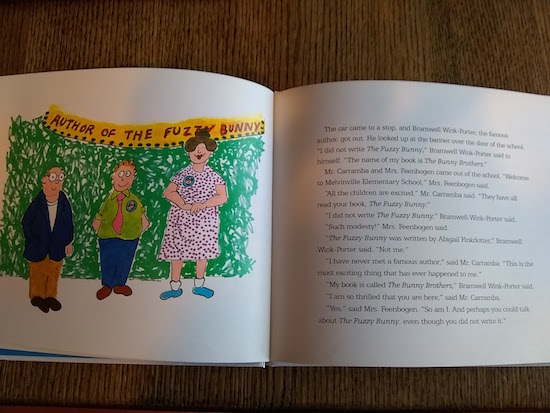

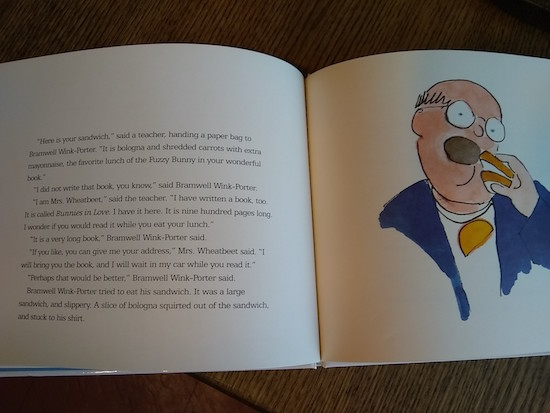

The plot is this: it’s Author’s Day. A banner is hung. Everybody at the school is very excited about the visit of Bramwell Wink-Porter, author of The Fuzzy Bunny. Except, “I did not write The Fuzzy Bunny,” says Bramwell Wink-Porter to himself when he reads the banner. “The name of my book is The Bunny Brothers.” When he informs the principal, Mrs. Feenbogen, she suggests, “[P]erhaps you can talk about The Fuzzy Bunny, even though you did not write it.” In the school library, there is a box of books for Bramwell Wink-Porter to sign, and the books in that box are Bunnies for Breakfast, written by Lemuel Crankstarter. But before anything can be sorted out, Wink-Porter is dragged off to the kindergarten where numerous sticky children insist on hugging him and feeding him pancakes with pieces of crayons in them. And then he arrives in Grade One, where the children have dressed up in Fuzzy Bunny Masks and Fuzzy Bunny hats. They ask him questions like, “Was it hard to write The Fuzzy Bunny?” And then he goes to the staff room, where a teacher gives him a sandwich that was the favourite sandwich of the fuzzy bunny in The Fuzzy Bunny.

“I did not write that book, you know, said Bramwell Wink-Porter.

“I am Mrs. Wheatbeet,” said the teacher. “I have written a book too. It is called Bunnies in Love. I have it here. It is nine hundred pages long. I wonder if you would read it while you eat your lunch… If you like, you can give me your address… I will bring you the book and I will wait in the car while you read it.”

…Another teacher sat down. “I am Mrs. Heatseat. I think it is wrong that animals do not wear clothes. I know you agree with me, because the Fuzzy Bunny always wears a raincoat.”

The fourth and fifth graders give him drawings of the Fuzzy Bunny on large sheets of paper with coloured chalk that gets all over his clothes. They let him pet their class bunny, who bites Bramwell Wink-Porter on the thumb. And then he goes to the sixth grade.

The sixth graders were waiting in the library. “Hey, doofus!” one of the sixth graders shouted. “You’ve got a slice of bologna stuck to your shirt, and there is coloured chalk all over your clothes!”

They end up tying Bramwell Wink-Porter to a chair.

And suddenly I feel better about everything, and very much not alone.

January 26, 2018

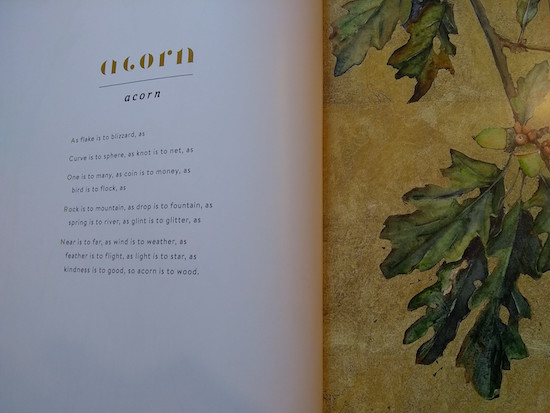

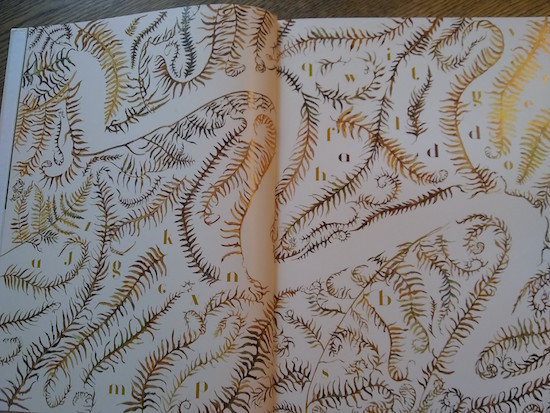

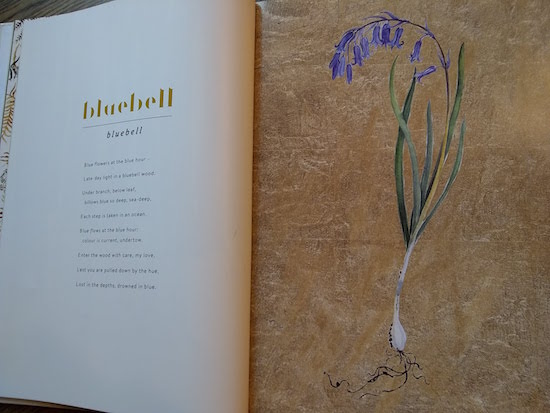

Picture Book Friday: The Lost Words

A bit of magic was delivered to our house this week with the arrival of The Lost Words, by Robert MacFarlane and Jackie Morris, which I first learned about via MacFarlane’s essay in The Guardian about how British children are losing the words to describe their country’s natural places. The Lost Words is a book about absence and things that are missing, this theme reflected in the title fonts with their missing pieces, and the two-page spreads in which an absence is shown by white space. The missing thing from each spread is shown on the next page in full colour illustration with an acrostic poem on the facing page, which sounds like the worst idea ever, but these poems are wonderful. “Rustle of grass, sudden susurrus, what/ the eye misses:/ For adder is as adder hisses.” And not poems, even, according to MacFarlane, but spells. “You hold in your hands a spell book for conjuring back these lost words,” he writes in a brief introduction. “To read it you will need to seek, find and speak.” And magic indeed are what these spells are—the one about the conker is absolutely perfect, about how it’s an object so magnificent (and isn’t it?) that it could not be manufactured. “…conker cannot be made,/ however you ask it, whatever word or tool you use,/ regardless of decree, Only one thing can conjure/ conker—and that thing is a tree.”

November 24, 2017

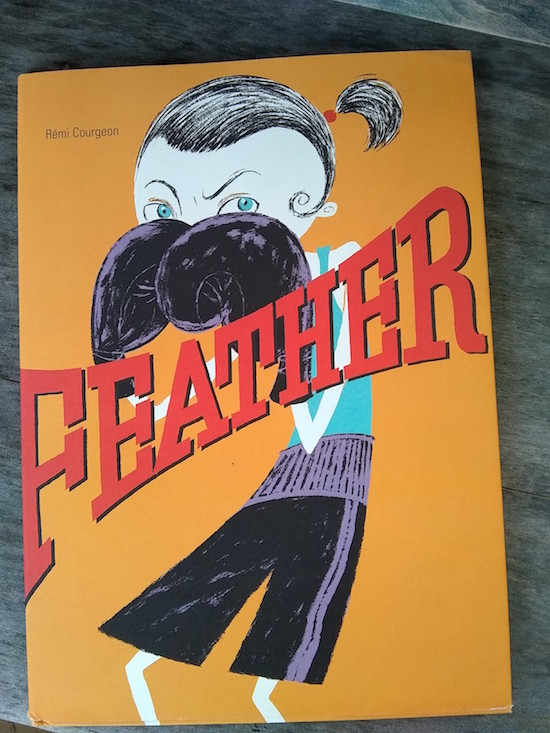

Feather, by Remy Courgeon

So I’m not exactly blazing a trail here, singing the praises of Feather, by Remi Bourgeon, which is included on the New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Books of 2017 list, but it’s a book we’ve been falling in love with more and more every time we read it.

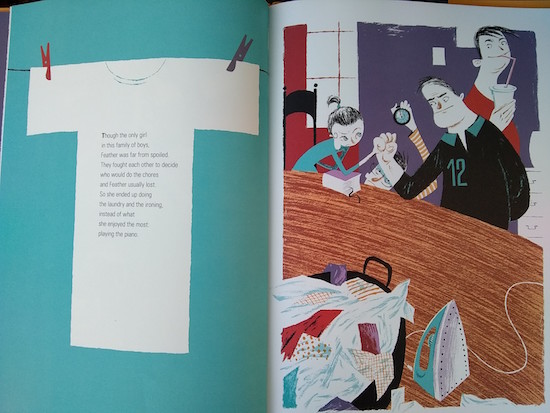

It’s an incredible exercise in minimalism, an entire novel so perfectly condensed into a few hundred works. Paulina is growing up in France, child of a Russian father who works all night driving taxis. Her mother, the reader assumes, has died, leaving Paulina the only girl in a household with three older brothers. She’s not just the youngest, but she is also the smallest—they’ve nicknamed her “Feather”—and when they end up fighting over household chores, she always loses, and ends up having to cook and do the laundry and she’s left with no time for her favourite occupation: playing the piano.

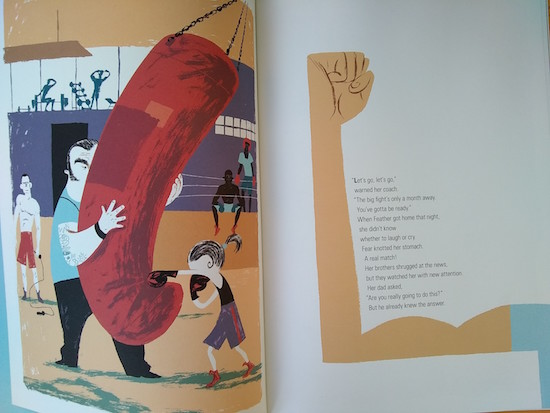

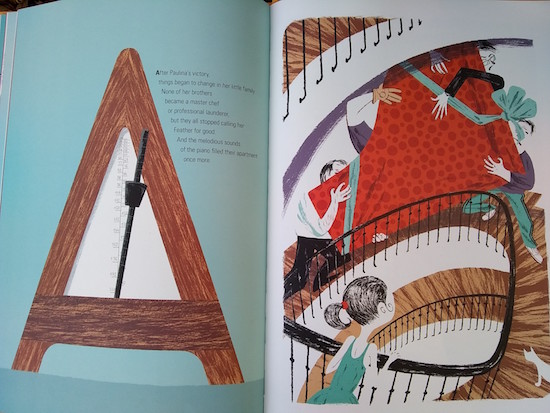

One day, after getting punched in the face and sporting a mean black eye, Feather announces that she’s quitting piano to take up boxing. No one can get her to change her mind, and she’s just as determined in her training as a fighter. Courgeon’s illustrations are fantastic, full of detail and action, and are so excellently married with the text in that the first letter of the first word on every pages is also a picture: see the L as the flexed arm below, the T in the t-shirt above, a J that is a cat’s tail dangling from the top of the piano, and an S that is a skipping rope. (And credit to translator Claudia Zoe Bedrick for making this work in English!)

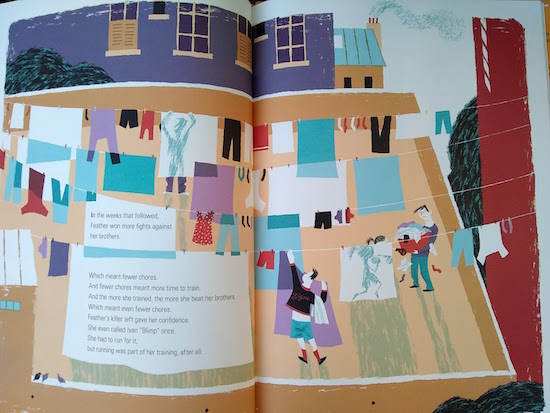

As Feather devotes herself to training, her brothers are forced to take on a greater load of the household chores, but mostly just because Feather starts winning the fights over who has to do them. “Feather’s killer left gave her confidence. She even called Ivan ‘Blimp’ once. She had to run for it, but running was part of her training, after all.”

Before every match, Feather gets ready by reciting “the names of women who had bravely made a place for themselves in the world: Rosa Parks, Marie Curie, Nellie Bly, Anna Lee Fisher, Sally Ride… She always ended with Nina Simone, because she had played the piano too.”

The book’s climax is the moment before the big fight, when Feather discovers notes from her brothers and her father hidden in her boxing glove, cheering her own. Her father has left a photo of her mother with a note on the back: “We’re with you, Paulina! Love, Dad.”

She wins, of course. You knew she would. And things do change around their house—she’s learned the respect of her rough and tumble older brothers But the surprising twist in the story is that she gives up boxing after that, and goes back to piano. “Fists should be opened and fingers should fly,” she explains, the last illustration showing a grownup Paulina playing piano with a baby on her lap and a boxing trophy on display.

The book’s final image is a boxing glove in the endpapers being used as a vase for flowers, and I love that idea. This is a fantastic book with a strong feminist message, but like all the best feminist things that message is not singular. This is a fun engaging book first and foremost, but it will also leave its reader with questions and things to think about, and a million other reasons to reopen the book and start reading gain.

November 19, 2017

Baby Cakes, by Theo Heras and Renne Benoit

When Harriet was three-years-old, I read Bringing Up Bebe: One American Mother Discovers the Wisdom of French Parenting, by Pamela Druckerman, and loved it mostly because it affirmed all the things I already believed about raising children and therefore I got to feel sophisticated and European, which is always nice when you’re only Canadian. And what I remember mostly about the book, apart from the fact its author had previously published an article in Marie Claire about giving her husband a threesome for his fortieth birthday, was the chapter on baking, and the recipe for yogurt cake. (There was also a chapter on babies sleeping through the night. That chapter didn’t work for me.) French children, according to Pamela Druckerman, bake all the time, and thereby learn about fractions and chemistry, plus stirring and pouring and patience and not spilling things. All of which were things that I could get behind, and so we made that cake, and we made it over and over, in addition to so many other cakes we’ve baked in all the years since. And that I’ve still yet to lose the weight from my last pregnancy suggests Druckerman may have omitted an essential detail in her text, which is that French mothers possibly don’t eat the food their children bake. But then where’s the fun in that?

We have a photo of Harriet from the first time we baked together, sometime in the months before she turned two, and she’s standing on a chair wearing an apron and holding a wooden spoon, and I tweeted the photo with some kind of caption like, “Basically I only really had children in anticipation of this moment.” Because I also remember standing on chairs while wielding a wooden spoon, and have such visceral childhood memories of baking, and I wanted Harriet to have to her own. Plus I wanted cake, of course, and so we baked, but it wasn’t always easy. My frequent admonishments of, “Don’t put your hands in the flour,” “Don’t sneeze in the batter,” and “Goddamn it to hell, you’ve just poured vanilla all over the floor” usually went unheeded, and we began to consider a baking session successful if I’d kept my swear words to a minimum of three. Baking with kids was often not as fun as it was made out to be. But I persisted—in addition to math and chemistry, I told myself, my children were learning about human fallibility (mine!) and also expanding their vocabularies.

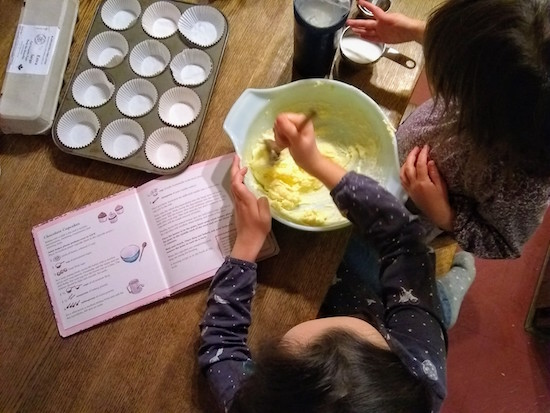

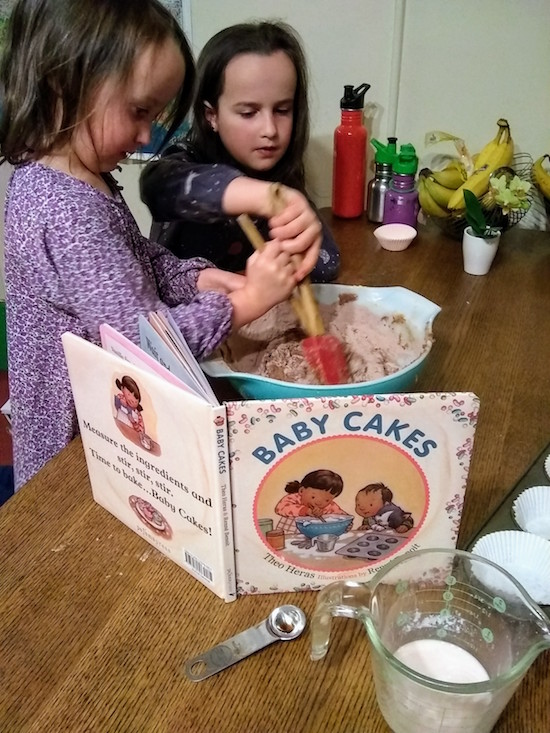

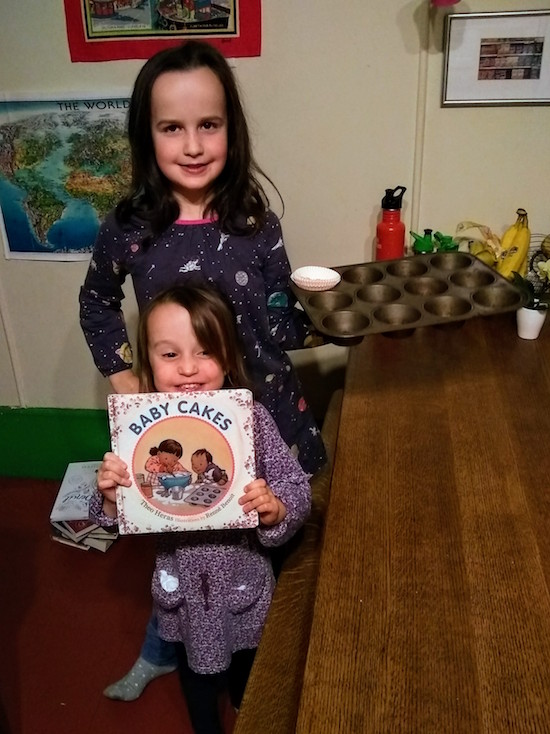

The very best thing about having children, however, (which is also the very worst thing) is that you basically get a new child every two weeks or so. Which is to say that everything changes, all the time, and the things that seemed impossible once upon a time eventually get to seem easy. Harriet sneezes in the batter hardly ever now, and when she and Iris sit down to baking they’re actually quite capable. And when I’d recently read Iris Baby Cakes, by Theo Heras and Renne Benoit, she’d declared, “That’s such a good book, Mommy.” Mostly because she’s obsessed with cupcakes, but still. Plus there was a recipe for cupcakes in the endpapers; I said, “We’ve got to make these.” And so on Saturday night, we did.

This book would make a great Christmas gift from 3-5-year-olds. With simple vocabulary, a brother and sister would together to make cupcakes (with the unhelpful assistance of their pet cat). The story lists the equipment necessary—”Here are a big bowl and measuring cups and spoons.”—and goes through the recipe, “Sprinkle salt, but not too much.” And “Creaming the butter is hard work.” And is it ever! The recipe inside makes for a nice extension of the book, bringing the story to life and inspiring the reader to try something new. That the brother and sister in the story bake together without the help of grown-ups (except for with the oven) inspires independence. Plus, the cupcakes were delicious. Obviously, I ate one. Because I am not French.

November 10, 2017

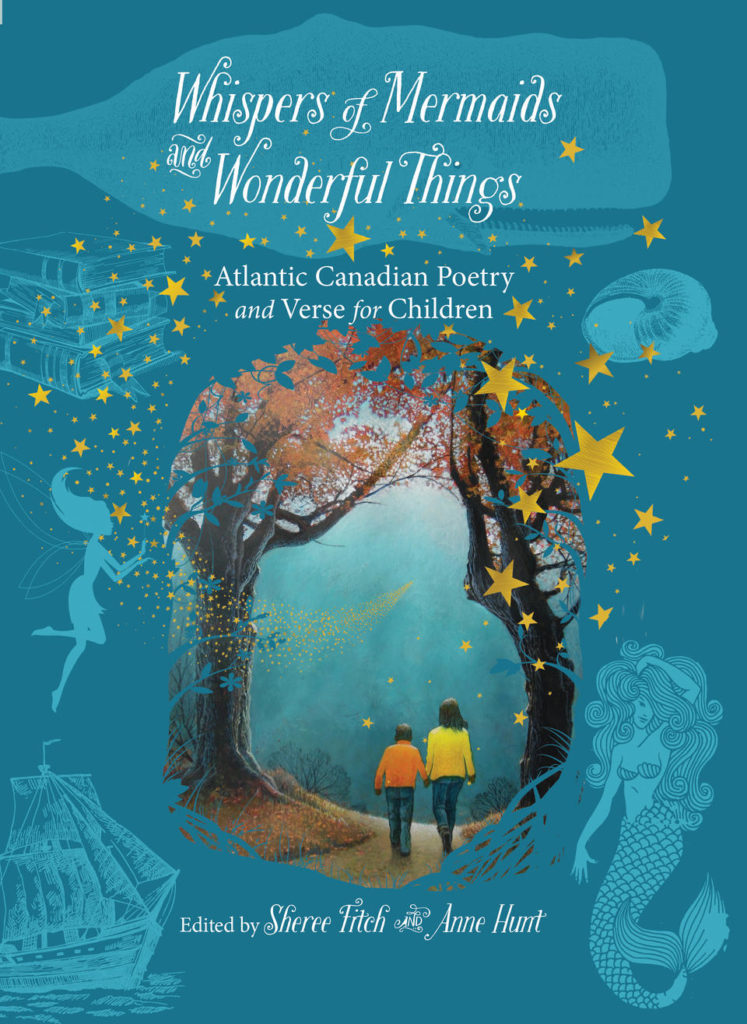

Whispers of Mermaids and Wonderful Things

Full disclosure necessitates I tell you that I had lunch with Sheree Fitch yesterday, although possibly I’m just telling you that because I’m still marvelling at the fact that I had lunch with Sheree Fitch yesterday. Sheree Fitch, whom we travelled to Nova Scotia to see this summer on the day her seasonal bookshop opened. Sheree Fitch is the most extraordinarily generous brilliant person I’ve ever known, a woman whose books have been the framework of my life as a mother and remember when a tiny Harriet crashed the stage to read with her at Eden Mills years and years ago? Although I was one of hundreds upon hundreds of people who traveled to River John, Nova Scotia, to see Sheree Fitch this some, because she is the sort of person who inspires such a gesture.

Even fuller disclosure: Everything Sheree Fitch touches is more than a little bit magic.

Although in the case of her latest project, the anthology Whispers of Mermaids and Wonderful Things: Atlantic Canadian Poetry and Verse for Children, co-edited with Anne Hunt, she’s not the only magic-maker. Credit belongs too to the designer of this gorgeous book whose cover art is absolutely enchanting, along with delightful leafy end pages, borders, and yellow ribbon to hold one’s place. And to her co-editor too, with whom Fitch has selected these works, and to the poets too, some of whom—Fitch herself, Jennifer McGrath, Kate Inglis, Al Pittman—I’m familiar with through their words for children, and others—Lynn Davies, Kathleen Winter, Sir Charles G.D. Roberts, E.J. Pratt, Alden Nowlan—I know if a very different context.

So how do you use a book like this, a pretty book with a ribbon, a book that isn’t a picture book because there aren’t any pictures? Which is to say, how does one awaken the magic within, the whispers of mermaids and wonderful things? And the answer, of course, is to read it. To take book off the shelf and leaf through at random, see where the pages fall open or where the poem catches your eye. To make a ritual of it, a poem before bed, perhaps, or first thing in the morning, like a vitamin. To revel in the words and rhymes, and share that wonder with the people around you. Let beginning readers have a chance to read these poems too, to experience the pleasure saying their phrases, how the words feel in their mouths.

This is a book that will make an extraordinary holiday present for (or from!) anyone with an affinity for words or poems, or an affiliation with Atlantic Canada. It’s such a beautiful object, a treasure, and then you open it up, and there are worlds upon worlds inside to explore.

November 3, 2017

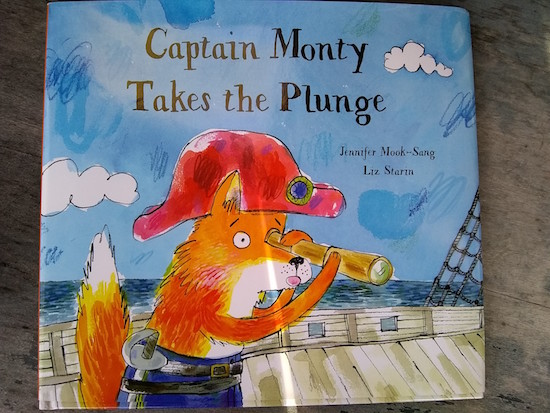

Captain Monty Takes the Plunge, by Jennifer Mook-Sang and Liz Starin

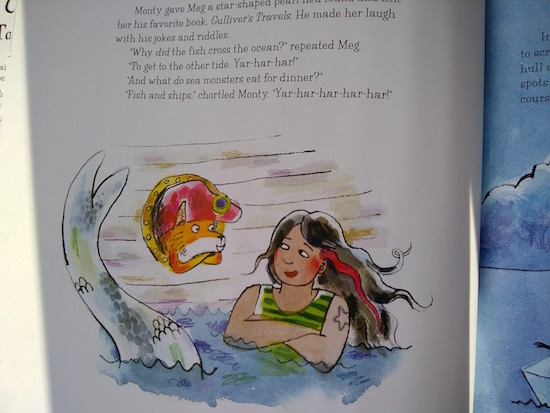

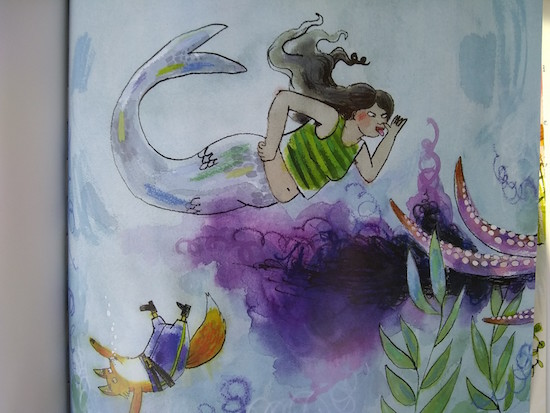

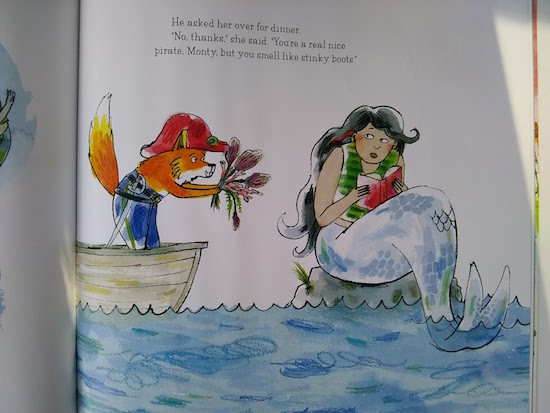

Is it wrong to fancy a mermaid? Well, it mustn’t be so wrong, because sailors have been doing so for centuries. But is it wrong to fancy a mermaid in a picture book? One who’s already in a relationship with a pirate who is also a cat? Well, if loving a picture book mermaid is wrong, I don’t want to be right.

And it’s not like Meg is just any picture book mermaid. “She’s like you, Mommy,” said my daughter. “She has a star tattoo.” And I remind my daughter, “We also both have awesome squishy tummies.” Because Meg the mermaid is the kind of mythical creature you want to have a lot in common with. She’s cool. She plays the ocarina, likes bad jokes, and she teaches Captain Monty how to set his course by the constellations, which is a useful thing for a pirate captain to know.

While she might be a punk rock mermaid, Meg still swims like a fish, displaying amazing skills that put poor Monty (who’s afraid of water) to shame. And she’s got standards too: when Monty asks her out, Meg turns him down. Because a guy who’s afraid of water never gets a chance to bathe, and she tells him, “You’re a real nice pirate, Monty, but you smell like stinky boots.”

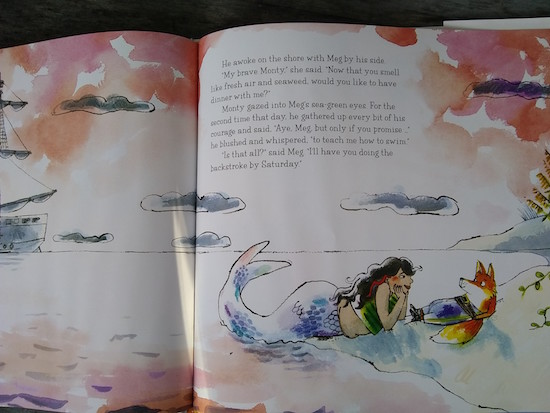

When Meg gets captured by an octopus, however, Monty has to step up to save her. Which he kind of fails at, until he thinks up a clever way to outwit the many-legged sea creature, and Meg joins in on the action, the two of them rescuing themselves together. And all that is pretty romantic, so of course they fall in love. “My brave Monty,” Meg tells him. “Now that you smell like fresh air and seaweed, would you like to have dinner with me?”

Captain Monty Takes the Plunge, by Jennifer Mook-Sang and Liz Starin, is a fun and lively book for any young reader who’s into pirates, dislikes bathing, and/or requires just a few more ounces of courage before she leaps into the pool. But it’s Meg who steals the show, a fabulously subversive and feminist rad mermaid, and she’s the reason we keep returning to the book again and again.

October 27, 2017

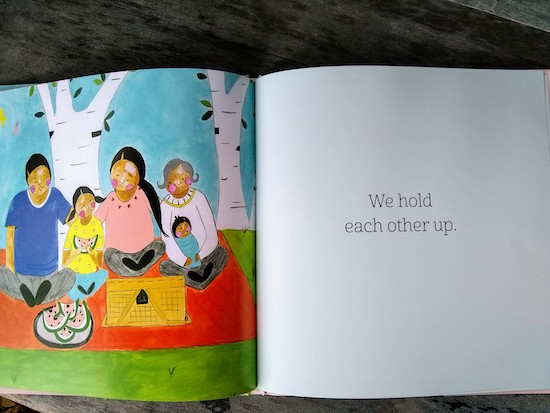

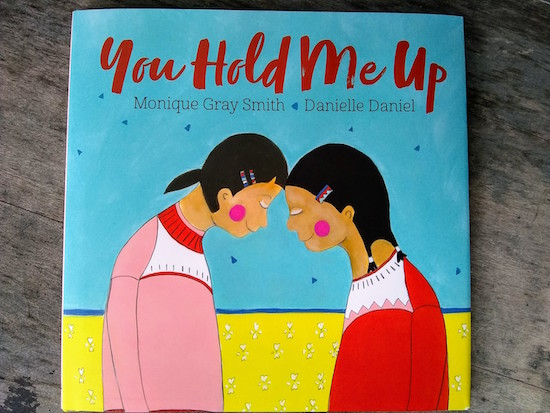

You Hold Me Up, by Monique Gray Smith and Danielle Daniel

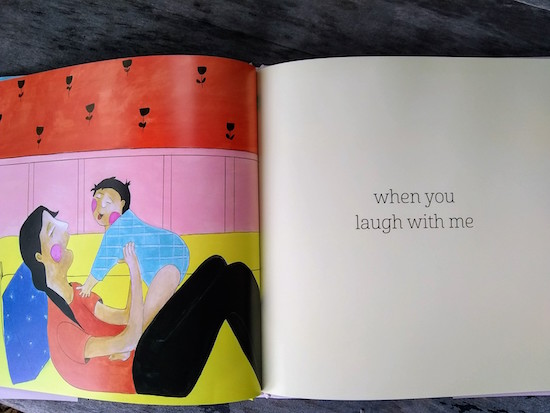

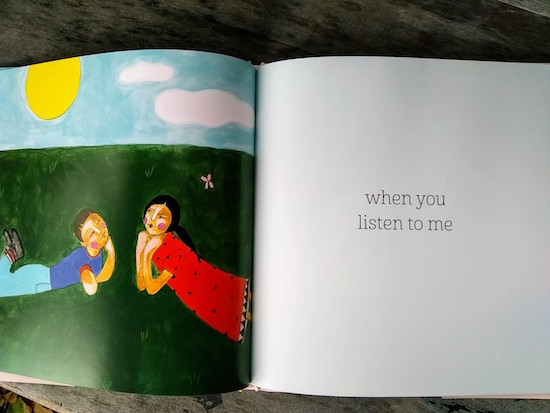

My children delighted in You Hold Me Up, by Monique Gray Smith and Danielle Daniel. As we read it, my littlest kept guessing what the text might be based on the image. “When you dance with me!” she offered, for the “you hold me up when you play with me” page, so she wasn’t wrong. She also guessed, “When you yawn with me,” for “when you sing with me,” which is a little bit wrong, but then we all started yawning, underlining the point of the book, that we’re all connected to each other.

Monique Gray Smith is the award-winning author of Tilly: A Story of Hope and Resilience, and children’s books My Heart Fills With Happiness (which I read last year) and Speaking Our Truth. I also really recommend her podcast, Love is Medicine. Illustrator Danielle Daniel won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award for her first book, Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, which we loved, has another new picture book just out, Once in a Blue Moon, and I also really liked her memoir for the adult set, The Dependent—my review is here. The idea of these two teaming up on a project has had me looking forward to You Hold Me Up for ages.

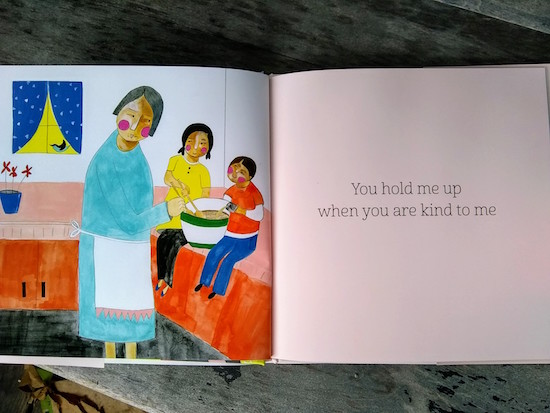

Smith’s text is simple, but powerful, about the small and essential ways we all support each other. “You hold me up when you are kind to me…” it begins, accompanied by a photo of an Indigenous family in the kitchen baking together. “…when you share with me…when you learn with me.” Daniel’s illustrations have a playful approach, but are also nicely stylized and textured, with a collage effect and fine details, warm and familiar images of people together.

“It’s about family,” Iris proclaimed when we got to the end of the story, the line, “We hold each other up,” with the facing image of two adults, their children, and a grandmother having a picnic under birch trees. And she’s not wrong here either, except it’s not only that. Smith writes in her Author’s Note of Canada’s “long history of legislation and policies that have affected the wellness of Indigenous children, families and communities.” Like her My Heart Fills With Happiness (and in everything she does, really) Smith is writing about survival and resilience, about the strength and power that comes from the love we give each other.