May 10, 2019

Alice At Naptime, by Shea Proulx

Sometimes I think that the story of motherhood is too big to fit onto a page, or into a book. Because having a baby is this way, and it’s that way, and it’s never one way, ever changing, impossible to properly articulate. Heather Birrell writes about this in her essay “Truth, Dare, Double Dare” in The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood. She writes:

“The trend..is toward a certain gross-out honesty—a “come join me here in the trenches” mordancy (“I just let her chew on the stroller tire!”) which, although funny and often a welcome release, leaves out the deeper resonances and rewards of being a mother and co-parent. Why is this? Because it’s hard to put your finger on the glint of joy in the dirty dishwater of drudgery. It slips away, seems a trick of the light, impossible to photograph, let alone articulate.”

But maybe you can draw it?

I am under the spell of Alice at Naptime, by Shea Proulx, who wrote in a post for 49th Shelf:

Drawings not only make clear the path of the body, but also the path of the mind, as text does, but differently from text. The world “psychedelic” is most associated with mind-altering substances, but the word breaks down from the Greek to mean “the mind…made clear.” Works of art that show clearly the mental processes involved in thinking through a subject might also be described as psychedelic, especially when the subject is inexpressible in words…

Alice at Naptime is a series of illustrations that Proulx drew of her daughter when she was a baby. “I used to draw all the time..” the book begins, “but now just at naptime.” And when Alice is napping, she draws Alice, her sleeping face set into kaleidoscopic scenes, a wonderland of strangeness, symmetry and doubleness that grows to fill the entire spread: “a symphony of Alices.” A kind of dreamland. And fittingly, for a child named Alice with illustrations that are definitely trippy, there is wonder: “Alice is strapped down so often when she naps. It looks like we’re worried she might float away.” What does Alice dream about? Proulx asks the reader, “Am I boring you?” And I remember the fascination of my sleeping child’s face, the smallness of my world then—I remember the day my child discovered causality while kicking an arch on a baby gym, and both our minds were blown, but nobody else cared. “It’s just that I’m so in love,” Proulx writes, “lost in a sea of Alice.”

What I love about this book is how Proulx shows the way that motherhood can inspire art and thought and creativity, rather than be its antithesis. That there is such profound love in the minutiae of parenting. It is like a dream, like a storm, rolling waves—and she started thinking about Alice growing, wondering who this sleeping baby will grow to be. (“What would it be like to wake up in different places all the time?”—but motherhood is a little bit like that as the years go on. My daughter turns ten this year. She’s known about causality for awhile now. Every day, we’re somewhere new.)

“I take Alice with me everywhere, even when I leave her at home.”

“Love can seem like a trap,” writes Proulx, confined to the place her baby is napping, to her baby’s needs and whims, “but I have roots now.” And it becomes clear that this book about a baby growing into a person is fundamentally the story of a woman growing into a mother—and also how she acknowledges that these sleeping napping days with Alice were only just a blink of an eye. (A dream?)

In a gorgeous afterword, Proulx writes about how it’s been years since she made these drawings. “I’m not the person I was then. You don’t become a mother all at once. You have to grow into that new self. I recognize the fragility of the tenuous identity I was sorting out as I relaxed into a new rhythm… It isn’t without sacrifice that women become mothers, or men fathers. But the gains are heady and by their nature, indescribable, as are many natural desires. I only hope I’ve done the process some small justice. I owe that to a former self, that new mom, adrift in a wonderland, wondering who she would become.”

May 3, 2019

Me, Toma and the Concrete Garden, by Andrew Larsen and Anne Villeneuve

Everything I’m hungry for in the world right now I can find within the pages of my friend Andrew Larsen’s new picture book, Me, Toma and the Concrete Garden, illustrated by Anne Villeneuve. It’s a book about cities and concrete, about connections and community. It’s about the beautiful things we grow by accident, and how small changes can have huge ramifications. But it’s also a story about two kids throwing balls of dirt over a fence, about meaningless fun, and my children like it too, compelled by the wonderful details in Villeneuve’s illustrations and also Larsen’s winsome narrative voice, which is my favourite thing about all his books. He writes voices that really sound like kids, kids who aren’t quite aware that their stories are bigger than the story they think they’re telling. There are lessons and morals in this book, but you’ve got to read between the lines to find them, which is what makes Larsen’s books—beloved by children—especially rich for adult readers as well.

April 12, 2019

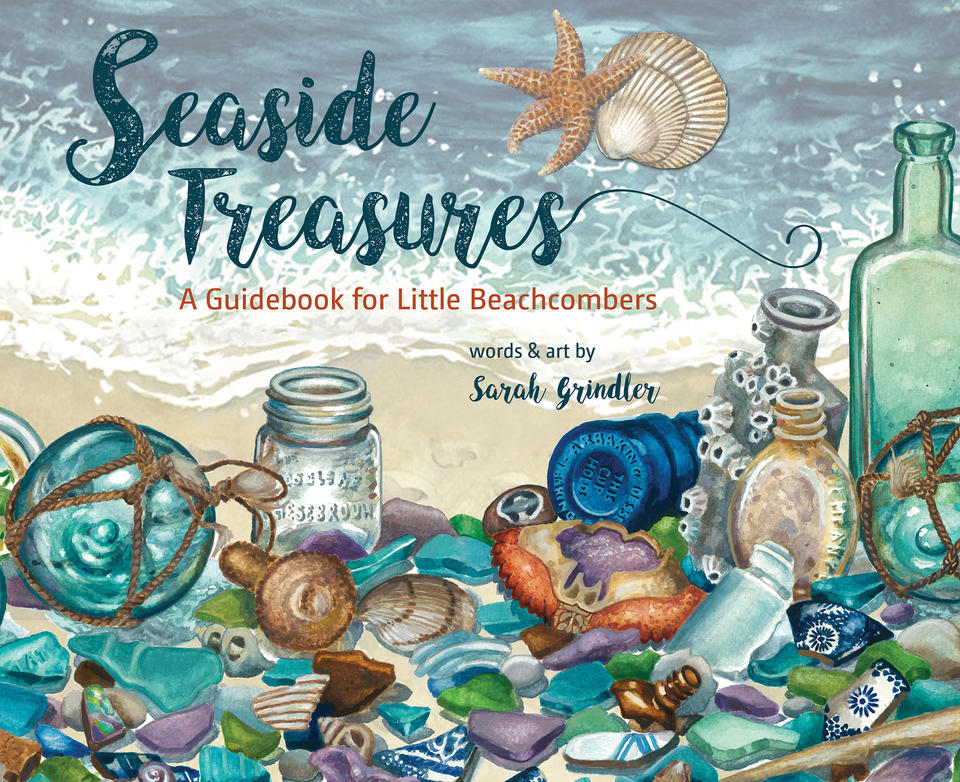

Seaside Treasures, by Sarah Grindler

This week has been aggravating for all kinds of reasons, macro and micro, and not least among the troubles is that people kept waking me up at 4am, and thereafter I’d lie awake in bed taking inventory of all the items that are weighing on my mind, which is no way to fall back to sleep, I tell you. So finally I came up with a plan, the night after I first read Seaside Treasures, by Sarah Grindler. My worries, I imagined, put away in a drawstring bag in the place where I was in my mind, which was the beach at Humber Bay Shores, a beach where the beach glass tends to be yellow, which fascinates me because out in the east end of the city it’s mostly green, and I wonder why the distinction. I would leave the bag behind me as I went to explore the beach instead, picking up mussel shells, slate perfect for skipping, round stones to hurl, and others with stripes to admire, the sun sparkling on the surface.

It’s possible I’m just dreaming of summer anyway, mid-April with snowflakes, but Seaside Treasures is a portal to there, and I love it so much. We’re beach treasure enthusiasts in our family, collectors of two glass jars of beach glass so far (and counting), with purple being ever elusive, but the odd fragment of painted china has made up for it in the meantime. And even though our beach is not a seaside, instead by a lake (but still, a GREAT lake) and we will never find a sand dollar or an urchin shell, this book is still right up our street, and makes us excited and inspired to go exploring local beaches again.

Grindler’s realistic painted illustrations are beautiful, a different hue for every page—blue sea glass, then purple—both rare. “Other hard-to-find sea glass colours are red, orange, and yellow You can find pieces of green, brown, and white glass more easily. What is your favourite colour of sea glass?” she asks, in text as engaging as the pictures are. She shows glass fishing floats, arrowheads from the Indigenous people who lived on these lands long before we did, seashells, and also pieces of china. “Do you wonder who might have used them? Perhaps sailors, merchants, or pirates!”

And then there’s garbage, which washes up among the rest of it, which led to a really interesting discussion (and a general consensus that cigarette butts are disgusting). Isn’t it funny that some garbage gets to be treasure and other isn’t? A marble on the beach is treasure indeed, but what about the toy car with its wheels missing? Grindler writes, “When I find garbage, I collect it to help keep our oceans and beaches clean.”

The final spreads invite the reader to search specific objects on a crowded page of beachy treasures, and then to imagine what kinds of art and objects could be made from these objects as well. Ending with a question: “What will you find?”

(Hopefully serenity.)

April 5, 2019

The Biggest Puddle in the World, by Mark Lee and Nathalie Dion

I’ve been meditating a lot on connection lately, how one thing leads to another, the ways that small things can cumulate in big things—which is the underlying message of The Biggest Puddle in the World, by Mark Lee and Nathalie Dion. But it’s a message that’s buried deep inside a wonderful old-fashioned story about two siblings who go to stay with their grandparents (Granny B. and Big T) for six whole days while their parents are away. In beautiful illustrations rich with gorgeous mismatched prints (damask wallpaper, floral duvet, mattress stripes to die for) we’re shown the siblings exploring their grandparents house as the weather outside just rains and rains and pretty soon the two are out of playtime options. But then: “The next morning patches of sunlight appeared on the kitchen floor.”

And so they head outside wth Big T. with a challenge: a search for “the biggest puddle in the world.” “The wet earth and the shiny grass smelled like spring. During the rain, a clump of mushrooms had popped up on a log.” They find one puddle, and then more puddles, but none of them constitute “the biggest puddle in the world.” Their grandfather encourages them, “Follow the water,” and they do, as the trickles from puddles turn into a stream, and then a pond. And they take a break from searching to create a puddle map, and then learn how puddles turn into clouds, which are made from bodies of waters everywhere, including that still-elusive big puddle that they’re looking for. Which they find by following a river through thorn bushes and down a muddle hill to reach a beach, and there it was: the ocean. The biggest puddle in the world!

The prose is lovely to read and the illustrations soft, dreamy and detailed, as absorbing as the story is. Just the book for April, and all its showers—it’s a perfect springtime read.

March 29, 2019

Nature All Around: Trees, by Pamela Hickman and Carolyn Gavin

My nine year old daughter Harriet knows everything, and she continually surprises me. Because who was it that taught her about constellations, garden slugs, axolotls, or the life cycle of a piraña? It wasn’t me, who still sometimes gets tulips and daffodils mixed up, and didn’t actually know what an iris looked like until after I’d given that name to a human. But it’s not altogether a mystery, where Harriet gets her knowledge from, because she’s an avid reader of nonfiction, devouring the “Do you know…” series from Fitzhenry and Whiteside, and Elise Gravel’s “Disgusting Critters” books. Every time we go to the library, she picks up another books about animals or plants—for a while she was really into fungi. (She also really likes Jess Keating’s books, her nonfiction and her novels alike.) But I have to confess that with some rare exceptions, children’s nonfiction books don’t really do it for me.

But then along comes Nature All Around: Trees, by Pamela Hickman and illustrated by Carolyn Gavin, a book that has been given a permanent home on our coffee table. Because it’s gorgeous, just the thing for those of us who are wild about botanical paintings, and a sensibility not dissimilar to Leanne Shapton’s beautiful Native Trees of Canada (with a sprinkling of Carson Ellis and Esme Shapiro).

I love this book! It’s beautiful just to leaf through (ha ha) with its paintings of leaves in their glorious variety, and filled with fascinating tree facts, the difference between a simple leaf and a compound leaf, explanations of photosynthesis, pollination, and features on “strange trees” like the 23-story tall sequoia that’s probably 2000 years old, or the larch tree, which is special because it’s coniferous and deciduous at once.

The terrible thing is that because I am not nine, my mind is a sieve, and I can never remember anything, which is a good excuse to keep this book on the coffee table—in addition to its pleasing aesthetics—because then I get to read it over and over again.

PS Another tree book I’m super looking forward to this spring is Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests, by the amazing Ariel Gordon.

March 15, 2019

Moon Wishes, by Patricia Storms, Guy Storms, and Milan Pavlovic

It was no contest what book I was going to write about for #PictureBookFriday this week, which has been the week of our March Break staycation, a marvellous week of travelling around town and taking in the best of what Toronto has to offer, which has included the Ai Weiwei exhibit at the Gardiner Museum, the library, a family swim, a return visit to Winter Stations at Woodbine beach, St. Lawrence Market and the Old Spaghetti Factory, and then yesterday, which was everybody’s highlight: a trip to see The Moon: A Voyage Through Time at the Aga Khan Museum, which was extraordinarily rich, and wondrous, and fascinating.

And which gave us a deeper appreciation for Moon Wishes, a new picture book from author/illustrator Patricia Storms, and one that is is written along with her husband, Guy Storms, and illustrated by Milan Pavlovic. And what a treasure this team has produced, a gorgeous story with images just as beautiful, a story about what the moon shines on, which just happens to be everything. (One of my favourite parts of the moon exhibit was the artist’s statement by Luke Jerram, who created the illuminated moon replica, who described the moon as “a cultural mirror.”)

“If I were the moon, I would paint ripples of light on wet canvas,” the book begins, and we see a school of fish swimming in the moon’s reflection. We see the moon shining over a group of migrants, all their belongings on their backs: “I would wax and wane over the Earth’s troubles…wishing peaceful sleep for worried hearts.” The moon is a constant, lighting up the darkness, always changing, just like everything is. “I would be a beacon for the lost and lonely…lighting the way home” And shining on all the creatures everywhere, in the sea, and on the land, in the woodlands, and on the coasts. Connecting all of us, both big and small.

March 8, 2019

The Secret Life of Alice Freeman…

Today at 49thShelf, we’re featuring an excerpt from new book Fierce: Five Women Who Shaped Canada, by Lisa Dalrymple and illustrated by Willow Dawson, which is a book I’ve been reading aloud to my family over the last two weeks, and one we’re all enjoying. In particular the story of Alice Freeman, Toronto schoolteacher in the 1880s who led a secret double-life as an investigative reporter. It’s so good, and you can read it here.

March 1, 2019

Climbing Shadows, by Shannon Bramer and Cindy Derby

I want to sing the praises of the kindergarten lunchtime supervisors, because it’s not often enough that people do. A job that is underpaid, under-appreciated, incompatible with most schedules, and without whom the school day could not proceed. When my eldest child was in kindergarten, her lunchtime supervisor was called Miss Vivian, and—I’m not sure if this is part is even true—all the children believed her to be a retired police officer from Jamaica. You didn’t mess with Miss Vivian, but then some people tried to, and one day my daughter told a story of a notorious boy in her class who’d pulled his pants down, which made me decide to send Miss Vivian a thank-you note for the work she did, plus a gift card for the liquor store.

Not everyone gets an LCBO gift card for being a kindergarten lunchtime supervisor, however. Poet and playwright Shannon Bramer got a collection of poetry instead, a poem for every child in the class that she’d worked with about anything they wanted. “Being a lunchtime supervisor in a kindergarten room involves container opening, orange peeling, snowsuit detangling, and mitten hunting,” she writes in her beautiful Author’s Note, and she also made it about poetry too. She shared the work of her favourite poets with the class, brought in illustrated collections to show them. “My kindies learned that poetry could make them feel and see and remember things. A poem could tell a sad story or it could make them laugh; it could make them think. A poem could be hard to understand beautiful to listen to at the same time.”

Lunch poems are not a new thing, but Bramer’s Climbing Shadows is my favourite twist on the concept yet, a collection that involved out of her collaboration with the children in the class, and which is published now by Groundwood Books with dreamy, appealing whimsical illustrations by Cindy Derby. Poems that remind me of children’s voices, their questions and preoccupations, but which also aren’t pandering and play and delight in language with the deftness of poetry intended for readers of any age. With enough familiarity to draw the reader in, but spaces between the words and lines enough to invite questions and wondering. Poems about octopuses, birthday parties, polka-dots.

“My mom is pushing the stroller/ through slush and broken ice/ and there’s lots of cold water shining/ on the street”

February 8, 2019

Pencil: A Story With a Point

I will admit to being a bit wary of Pencil: A Story With a Point, by Ann Ingalls and Canadian illustrator Dean Griffiths. I am not convinced that the world necessarily needs more stories about anthropomorphized writing or colouring implements, plus I’d flipped through and saw it was also a story about the perils of too much screen time, and I’m wary of morals and screen fear-mongering. But the illustrations are very appealing (including very cool endpapers) so I sat down to read this with my daughter, and told her, “If we’re going to like this book, it’s going to have to be really good.”

And it was. Primarily, because (as might be discerned from the book’s subtitle) Pencil is playful with language and we never got tired of the puns–”You don’t measure up,” says the ruler in the junk drawer, alongside the spare battery who says, “He’ll get a real charge out of that/ ‘”Happy to hold things together,” said Paper Clip and Tape.’ It goes on, ‘”You’re a cut above the rest,’ said Scissors/ “Our friendship is permanent,” said Marker.’

And while this indeed a pencil versus tablet story for our screen saturated age, it’s also more interesting than just that, about a boy who loved his pencil until he abandoned it for tablet pursuits, and then Pencil was rescued from the junk drawer by the boy’s sister, and was there to see it happen: the tablet crashing to the floor and breaking, the boy distraught. Is there anything that Pencil can do?

The part where Pencil fails to make the boy feel better by showing him all the awesome things pencils can do (“He could be a tent pole for a really small tent.”) was very funny, and then, with the help of his junk drawer friends, Pencil arrives at an ingenious solution. Pencil and the boy are reunited. A happy ending to this warm and humorous book which demonstrates that a story with a point is not necessarily a bad thing. It’s all in the delivery, and this one is done right.

January 25, 2019

A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader

Confession: There are some beautiful books in my house that I have never read. Oversized coffee table volumes with gorgeous design, ribbon bookmarks, incredible illustrations, fascinatingly edited, but they’re more furniture than literature. Or maybe they’re aren’t, but I’m unlikely to ever find out, because while I appreciate these books as objects, nothing has ever compelled me to sit down and start reading them. But A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader, edited by Maria Popova and Claudia Bedrick, a beautiful book with endpapers to die for? Reader: I read it all, many parts aloud. A book that’s as good as its package; even, a book for the ages—all of them.

This collaboration is a “labour of love” between Popova (of Brainpicker) and Bedrick (publisher of Enchanted Lion Books), with all proceeds benefitting the New York Public Library system, and situated as a demonstration that “a life of reading is a richer, nobler, larger, more shimmering life.” It’s a collection of letters from readers—who also happen to be writers, rock stars, astrophysicists, artists, business moguls, philosophers, Lemony Snickett, Shona Rhimes, activists, composers, radio producers, Judy Blume, and more—about the role of reading in shaping their lives. There’s Rebecca Solnit, and Maud Newton, and Mary Oliver, and Leonard Marcus, and Ann Patchett, and Yo Yo Ma, and Shirley Manson, and Jane Goodall, and Ursula K. Leguin, and so many others, each letter paired with an illustration by artists including Maira Kalman, Isabelle Arsenault, Liniers, Olivers Jeffers, Marianne Dubuc, Shaun Tan, and more.

It’s a beautiful, thoughtful, inspiring book, and the greatest thing I got from it was company. Because while I appreciate the solidarity I share with my bookish friends online and in the world, I have increasingly, lately, wondered if we are outnumbered in the general population. As I read statistics on how few adults read for pleasure, about declining book sales, as I hear one more person who binge-watches Netflix talk about how they just can’t find the time to read. I despair for a future in which people don’t understand the value of reading and the riches that books can deliver us… but then this beautiful book is a reminder that it’s not all lost. Not yet. That these riches are still abundant, and foundational, they bring us together, and they remind us that the world is amazing. Still.