June 26, 2015

My Favourite Things and Ah-ha to Zig-Zag by Maira Kalman

In 15 years of blogging, I am not sure there’s a post I’m more proud of than the one I wrote last fall about my accidental discovery of the artist Maira Kalman (and of how that led to cake). Coming to Maira Kalman was a curious experience rich with signs and wonders, like the United Pickle label on the back of The Principals of Uncertainty, and the title of the book at all because I would have purchased any volume called such a thing. Not to mention that hers are picture books for grown-ups, which I so completely delight in, and so I was thrilled to receive for my birthday yesterday a copy of her book, My Favourite Things.

“Isn’t that the only way to CURATE A LIFE? To live among things that make you GASP with delight?” Kalman writes, which is just one of the many points at which this book had me nodding and gesturing emphatically. And yes, GASPing with delight.

My Favourite Things is as random as its title suggests, art and writing about various objects. Part 1 is “There Was a Simple and Grader Life,” which explores Kalman’s family history through items including a grey suit belonging to her father, a grater for making potato pancakes, and her aunt’s bathtub in which fish would swim “waiting to become Friday Night dinner.” Part 3 is called “Coda: or some other things the author collects and/or likes” (including “bathtubs, buttons and books”) and the middle section of the book was born from Kalman’s experience curating an exhibit of her favourite items from The Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum.

My children were excited to realize that they recognized many parts of the second section of my new book, because I’d bought them a copy of Kalman’s children’s book Ah-hA to Zig-Zag last December.

It was a book they had some trouble with at first because Kalman’s zaniness is a bit lost on the childhood mind which is so often looking for things to make sense and for books to have stories. But Kalman’s unorthodox A-Z (which, like My Favourite Things, is also a tour though objects from her exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt ) grew on them, and they can appreciate its strangeness now that it’s familiar (and they like the image of the cutest dog on earth, as well as the picture of the toilet in the middle of the alphabet—”Now might be a good time to go to the bathroom. No worries. We will wait for you. Not a problem.”—as a bathroom visit is essential to any museum experience [although it’s curious that she never makes it to the cafe.])

(As a notorious imperfectionist, I am also partial to O.)

Not only do Kalman’s books celebrate the marvellousness of things, the books themselves are marvellous things in their own right. They’re things that (literally) speak to you (Ah-hA! There you are. Are you ready to read the Alphabet?…), and unless I’m particularly singular (unlikely) you too will find that Kalman’s curated collections will speak to you in other ways too, connecting with your experience in an uncanny manner, making you suspect that Kalman’s been eavesdropping on your soul.

The only trouble with the overlap between Ah-Ha! and My Favourite Things is that my youngest daughter keeps getting frustrated by being unable to find the toilet in the latter, though that is just another example of how these beautiful puzzling books are so wholly engaging. Having a few of them lying around the house is not a bad to curate a life after all.

June 19, 2015

Butterfly Park by Elly Mackay

I bought Butterfly Park because Sara O’Leary named it as a hypothetical Sadie Summer Read in our 49th Shelf interview, and then I saw it featured on the wonderful children’s literature website, kinderlit. When I finally laid eyes on on the actual book, it was inevitable that we’d own it. It’s beautiful, magical, and infused with the same sense of wonder that is so compelling about This is Sadie.

The story is simple, and not really ground-breaking: a young girl moves from the lush countryside to a dank and dirty town. The one spot of hope is a park beside her house with an elaborate gate and a sign reading, “Butterfly Park.”

But when the girl goes inside, there is not a butterfly to be found. With the help of other children in the neighbourhood, however, the girl embarks upon a quest to make Butterfly Park live up to its name, and the whole community is awakened in the process.

While the story is pretty basic, the book’s depth comes from its illustrations—literal dept and otherwise. Mackay’s images are extraordinary, paper cut-outs painted and assembled in three dimensional scenes in a wooden frame, and then photographed. There is a an old-fashioned Victorian postcard feel to the children she has painted, except that her children show diversity in their skin colours, which is wonderful. And it’s remarkable to consider that her exquisite detail has been rendered in paper cut-outs—I’m especially fond of her clotheslines, garden gnomes, and all the other perfect little things in the corners of her scenes.

My favourite thing about Butterfly Park is MacKay’s rich and warm use of light, which indicate the passage of time and time of day. Her glowing oranges and yellow are beautiful to behold and add event more texture to this images, if such a thing is possible.

I also appreciate how my daughter’s response to reading the book was a very This is Sadie-like move to go out and make something. “Mom, I need the scissors,” she said, and got to work cutting out bits of paper in a way she hadn’t done since she was three (which, if you are a parent, you will know is most children’s peak cutting-out-bits-of-paper period). I also love how the book’s conclusion underlines things I’ve been thinking about lately about gardening as community building.

Plants need roots to grow, indeed.

June 11, 2015

Harriet, You’ll Drive Me Wild by Mem Fox and Marla Frazee

Okay, can we just stop for a moment while I tell you how I worship at the feet of Marla Frazee‘s entire career? The woman behind some of the great picture books ever—Everywhere Babies, The Seven Silly Eaters, and All the World. Her own books too—Roller Coaster and The Farmer and the Clown. Her images are so vibrant, complex, textured, diverse, her world so detailed, her babies so perfect, and her toddlers so perfect…ly devious. I love her. I love her. I do.

I read somewhere once (or else I dreamed it?) that Marla Frazee was not the original illustrator for Harriet You’ll Drive Me Wild, and that there exists somewhere a completely different edition of this book. I am unclear as to the veracity of this rumour not just because I can’t find a single shred of evidence supporting it, but more because it seems unfathomable. (Update: but it’s true! The book was first published in 1986 as Just Like That, illustrated by Kilmeny Niland.)

My neighbours gave me their old copy of this book (the 2003 edition) when my Harriet was three weeks old. I remember sitting in the chair by the window, the scene of innumerable struggles to get the baby to latch, and how here was a book very different than the others we’d been reading in that storm. Different from the new parenting books I’d already filled with my manic marginalia, and different from the baby board books with their saccharine endings (which were somehow always about going to sleep. I wondered, when was that part going to happen?). Here was a book that gave me a glimpse of the future, of a time in which my new baby might not be small enough to tuck in neatly across my chest as we napped on the couch—shocking. A glimpse of a child-to-be, full of energy, beans and mischief.

Where Fox’s Harriet was once my future, six years later, she’s now the past. The character is about three, I think, not intending any trouble (which, according to the text, always happens “just like that”). Frazee’s images show another reality, however, of squirms, experiments, curiosity, contortions and shenanigans—but still, she can’t help herself. “Harriet Harris was a pesky child. She didn’t mean to be. She just was.”

There are so many things I love about this book. First, that it’s Mem Fox, whose work has been so essential to my happiness as a parent. (Read Where is the Green Sheep and not be happy. I dare you.) Second, it’s a literary Harriet, and we love these. Third, that it depicts a very realistic mother, a bit frumpy and struggling to get her own things done while her daughter thwarts her at every turn. (I imagine that between the pages, she is ignoring her daughter and scrolling through Twitter.) And shows that a mother can get angry (for good reason) but that this is okay. Things—people and pillows—can explode, but that doesn’t mean that it can’t be made all right again.

But the foremost reason I love this book is because of the text, and how the lines build on one another along with the mother’s frustration. She begins with her patience tested, saying (because she doesn’t like to yell), “Harriet my darling child. Harriet, you’ll drive me wild.” And that added on to that by the end is, “Harriet, sweetheart, what are we to do? Harriet Harris, I’m talking to you.” Delivered in harassed mother voice. The alliteration of the name is delicious to say, along with the rhyme. I love the consternation.

Reading the part of a mother in a book is rarely quite so nuanced and interesting.

June 4, 2015

Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney

The reason why Barbara Cooney’s Miss Rumphius was one of my favourite books as a child was because of its expansiveness. In terms of geography—we see images from her travels all around the globe, and on a micro level as she winds her way along paths and roads in her New England town so that we see the school, the church, the houses of her neighbours. Images on the horizon and ships on the sea (and the highways that stretch off the page in two directions) suggest interconnectivity, the wider world, a sense of wholeness. And so too does Cooney portray a single life with such largesse, beginning with young Alice as a child painting in the skies in her father’s pictures, and finishing with Alice as an old old lady (as narrated by her grand-neice), as well as everything in between.

As an adult reader, I still admire the hugeness of Cooney’s canvas, but I am most fond of the book for its feminist overtones. Because here we have young Alice who knows exactly what she’s going to do with her life—she’s going to travel to far away places, and then come home to live beside the sea. (There is a third thing she must do, according to her grandfather—she must make the world a more beautiful place.) Here then is the story of a woman’s life that neither begins nor ends with a wedding—in fact, there isn’t a wedding at all. I suppose we’d call her a spinster, but she’s a woman who’s always been called by her own name: Miss Rumphius, The Lupine Lady, Great Aunt Alice. (Admittedly, she is also referred to as That Crazy Old Lady, but she doesn’t appear particularly bothered.)

Here is the story of a woman who goes through the world sowing her seeds, leaving her mark, living precisely as she said she would. She doesn’t stop travelling the world and courting adventure until she hurts her back getting off a camel, and only then does she come home to her place beside the sea. She doesn’t conform to society’s expectations of femininity, but lives by her own rules. (A similar plot is more explicit in Cooney’s picture book, Hattie and the Waves. Cooney has described both books, as well as Island Boy, as as close as she’d ever come to writing an autobiography. Surprisingly though, Cooney was married—twice!)

As a feminist, it’s possible that this was my foundational text.

There are a few troubling points about the book involving cultural stereotypes. See Debbie Reese’s post about what’s wrong with the reference to the cigar store Indian, and I’m also uncomfortable with the colonial feel of Miss Rumphius’s travels throughout the world. Both issues can be the start of worthwhile discussions with young readers though, two of many spurned on by the richness of Cooney’s words and images. These points should not be ignored, but are no good reason to throw the book out altogether.

I love so many things about this book. That it’s an entire lifetime distilled into a few words and pictures, that she works as a librarian, the greenhouse, the cat, that she gets sick and then gets better again, that the story affords that life itself brings bumps along the way. It’s the kind of books whose illustrations I’d get lost in, tracing my fingers down the roads, examining the details of the paintings on the wall. And the light of the sunset on the very last page, the children gathering lupines that Miss Rumphius planted. I love the cyclical nature of the story, it’s open end, which is a challenge to the reader herself.

Throughout summer, I will be devoting Picture Book Fridays to classic picture books I love.

May 28, 2015

What’s Inside? by Isabel Minhós Martins and Madalena Matosa

Now that Harriet is older and learning to read on her own, I have a particular appreciation for picture books that are less text-oriented—their game and puzzle nature reminds us that reading is meant to be fun, they’re fun for us to engage with together, and Harriet is content to explore the pages on her own time. But wordlessness makes the stakes are a bit higher—a book like this has to be really good, excellent in both its art and its premise. And What’s Inside? by Isabel Minhós Martins and Madalena Matosa satisfies certainly on both counts.

Published in English by Tate Publishing, the publisher of visual art books associated with London’s Tate Gallery, What’s Inside? was created by the Portuguese duo behind several popular books including When I Was Born. On one hand, What’s Inside? is a kind of inverted Kim’s Game in which readers are delivered a pictorial inventory of interesting vessels and spaces—the hall table drawer, Mum’s handbag, the kitchen counter, my bedroom wall—and then asked to answer questions and find specific details about the objects at hand. Many of these questions are answered on subsequent pages, or lost objects found, separated pairs matched, and broken bits pieced back together.

The questions are great, open-ended, and allow for flights of the imagination (as well as real satisfaction for those who finally locate, for example, just where is Mum’s missing earring after all). What’s really wonderful about the book, however, is how a narrative emerges from all this stuff—we get a sense of who these people are, what are their preoccupations, their quirks and oddities. (Why indeed is there an Ace of Spades in the refrigerator?) Some of the deeper mysteries are never really answered, or at least I have not found the answer to yet, for example to why exactly a wooly hat was brought to the beach—though we have speculated that perhaps the grandmother was knitting it? She had a ball of yarn in her beach bag after all. Perhaps the hat was her finished product? Which is the best thing—how the stories in this story lead us to tell stories of our own.

Readers will delight in the familiarity of household objects, puzzle at the stranger ones, and perhaps begin to think more deeply about what their own stuff says about them. And for those who manage to eventually make their way to the book’s last page, it isn’t finished yet. “Open Your Eyes and Discover More,” the authors implore us, with a list of questions that urge us to go even deeper.

May 21, 2015

This is Sadie by Sara O’Leary and Julie Morstad

I have a special affinity for This is Sadie, the gorgeous new collaboration by Sara O’Leary and Julie Morstad (whose When You Were Small and other books in the Henry series I have loved since before I had my own small people to love them with). I like to imagine it was written just for me.

It’s got bunting, and swimming, and tea parties, and paper dolls, and even squids, and a spirited girl who gets lost in a whole wide world of books.

It’s got everything that made Morstad’s award-winning How To so wonderful—the mermaid girl, a pair of legs revealing someone hiding in a tree. Plus, O’Leary provides the mischief of Judith Viorst’s and Hilary Knight’s Sunday Morning, the bookish inspiration of Charlie Cook’s Favourite Book by Julia Donaldson, and allusions to Alice in Wonderland, The Jungle Book, Little Red Riding Hood, and Rapunzel. It’s a book about passing time. reading books, and how Sadie likes to make “boats of boxes/ and castles out of cushions./ But more than anything she likes stories,/ because you can make them from nothing at all.” We see Sadie in bed reading a book called The Story of a Snail, then by the next page, her boat box has been transformed into a snail shell.

Morstad’s illustrations are full of jokes and details, things to discover—an apple with a bite out of it, Sadie’s abandoned shoes, a toadstool bedside lamp, a mysterious family of tiny foxes. The book reminds me of Carson Ellis’s Home in how things from around Sadie’s room and in her books recur as images in her imaginings—just as Ellis’s own artist uses the things around her as inspiration for the illustrations in her book. Both This is Sadie and Home make connections between the world around us and where we go in our dreams.

And what anyone needs for dreaming is room to explore. “In This is Sadie, it is pretty easy to draw a direct line between boredom and creativity,” writes O’Leary on her blog, underlining the importance of giving kids the opportunity to make their own play, to dream their way into all kinds of stories—the mermaid, the boy raised by wolves, and “the hero in the world of fairy tales.”

“The days are never long enough for Sadie. So many things to make and do and be.”

May 14, 2015

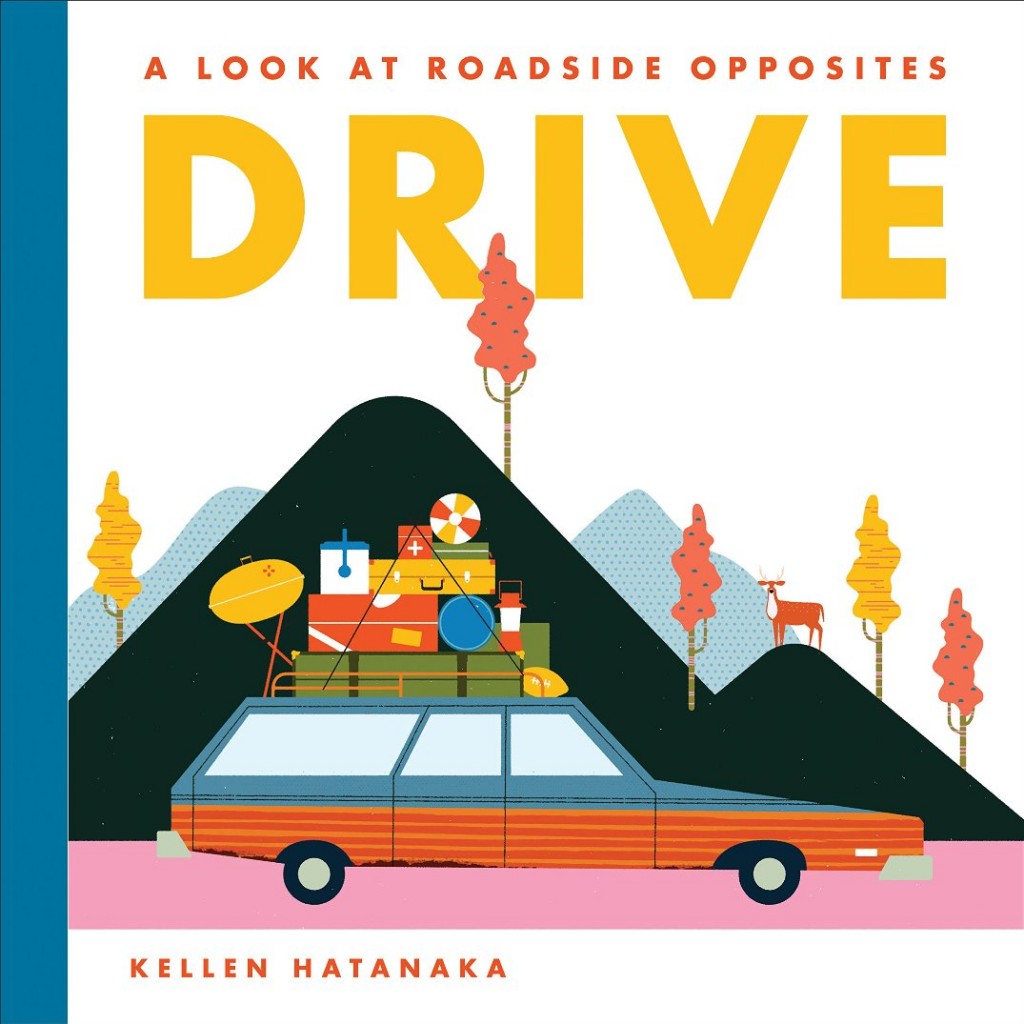

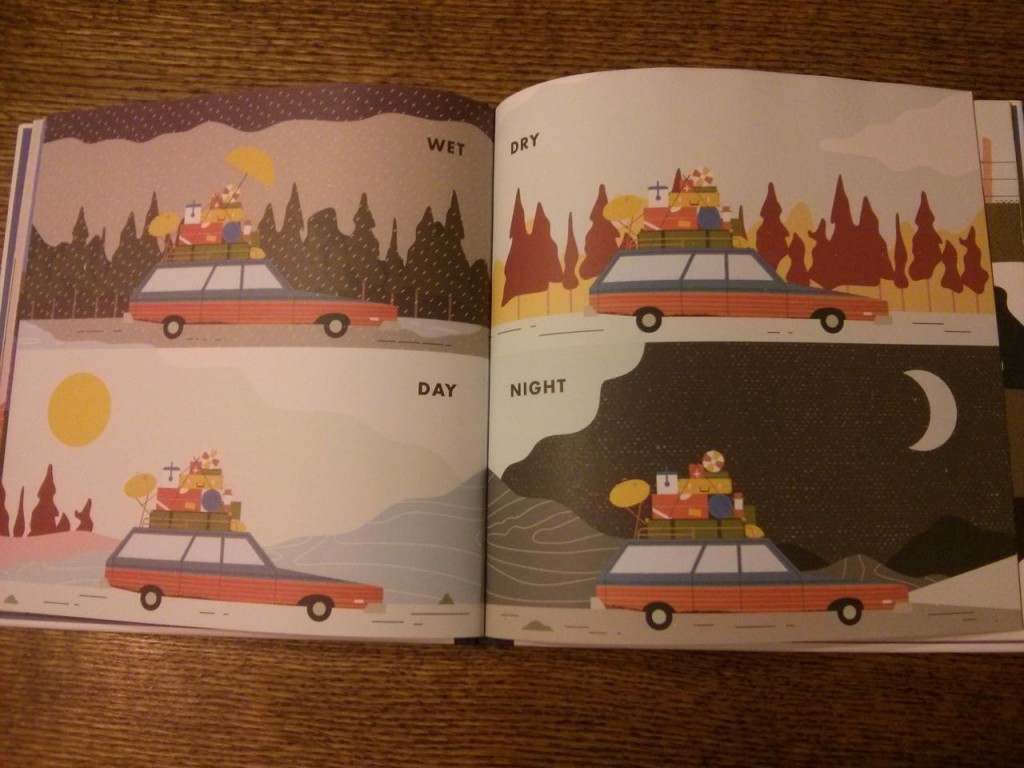

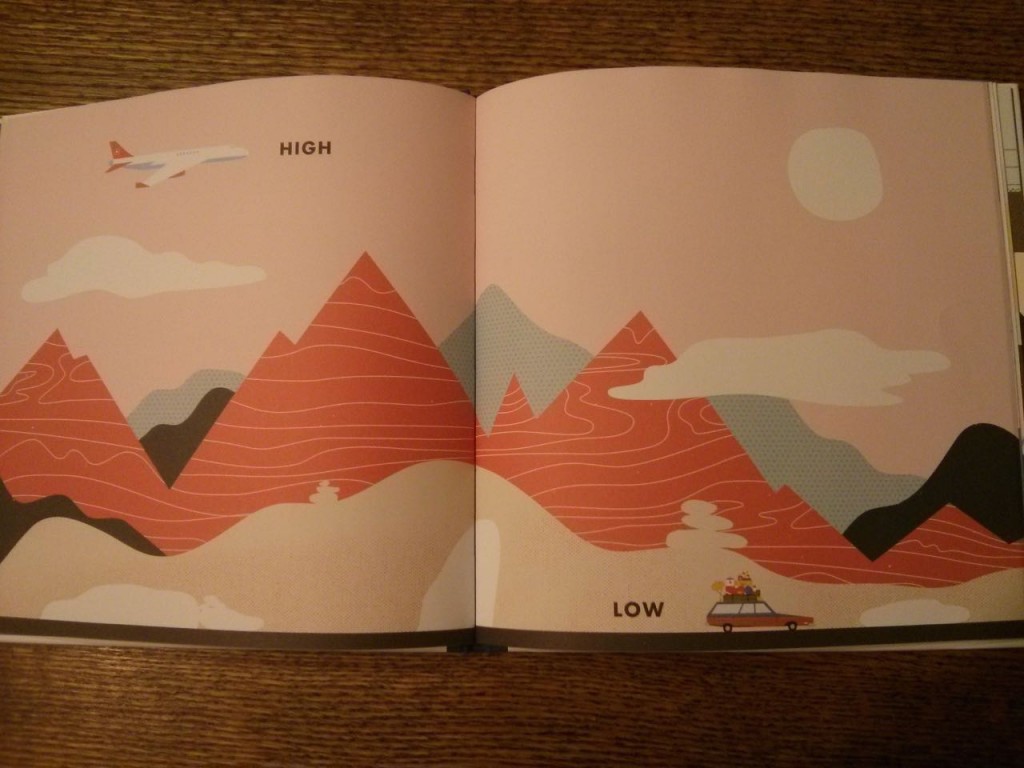

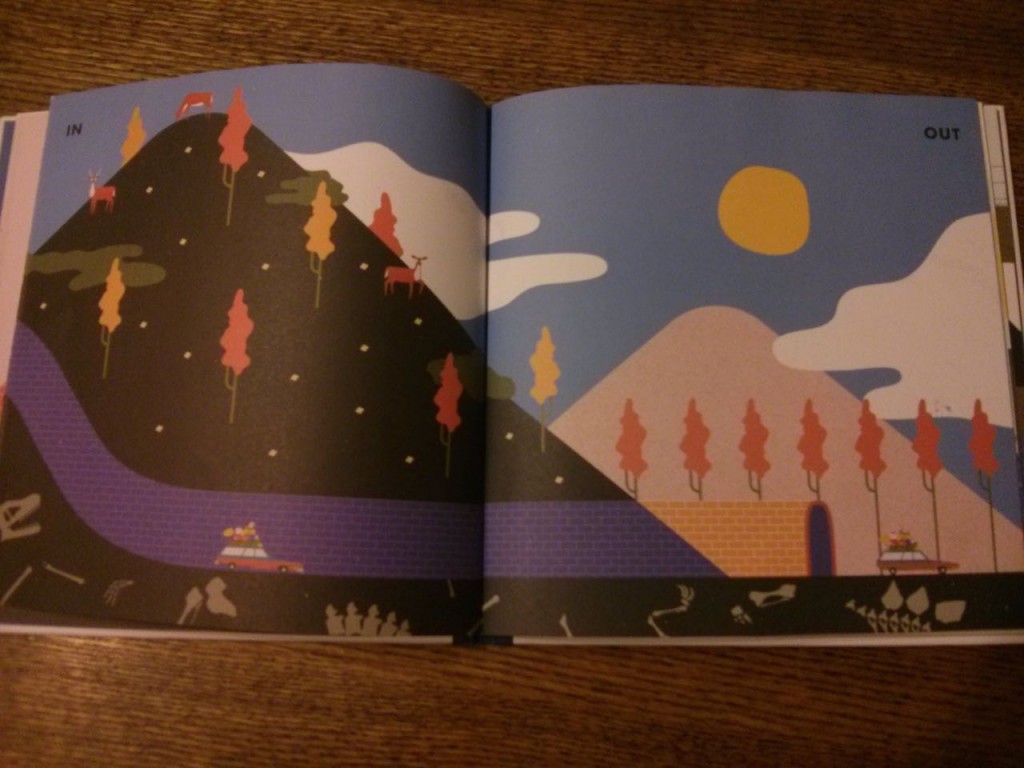

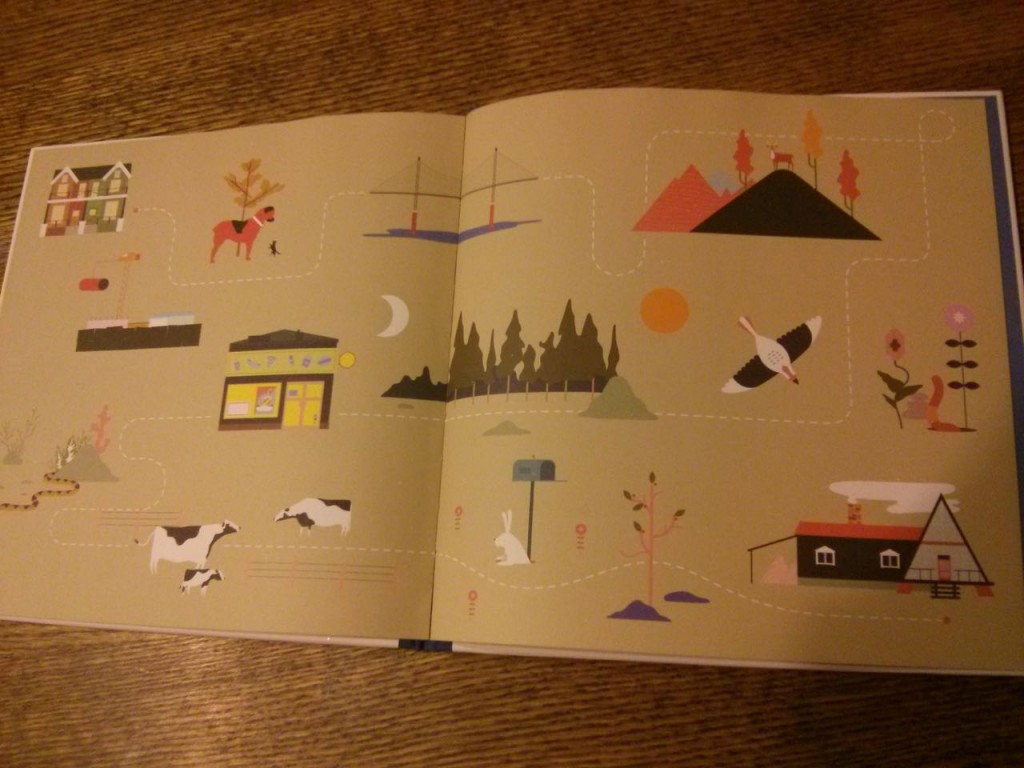

Drive by Kellen Hatanaka

Mad Men ends on Sunday, after years and years, and in tribute to my favourite show, I’ve picked a picture book this week with a similar aesthetic. I think Betty Draper even owned that station wagon exactly. Drive: A Look at Roadside Opposites is the second book by Kellen Hatanaka, whose Work: An Occupational ABC was on my Hipster Picture Book list last year. While this new book is similarly focussed on design, it’s got more of a narrative, and I like it even better than the first one.

Drive is the story of a journey toward a summer holiday, from the city to the country, and therefore a natural setting for I-spying opposites. The car is packed with summer things—a barbecue and beach balls—and we can only imagine the Are We There Yets? before they finally arrive.

But in the meantime, there is looking out the window. Big, small. Above, below. Winding roads and straight ones.

With all of these Don Draper is actually DB Cooper rumours, this page seems particular eerie.

The illustrations are fantastic, full of funny and interesting details. We particularly like the dinosaurs bones under the mountain in the image below. As with his previous book, Hatanaka plays up the unexpected—I love the “Worm’s Eye View” that opens up into a four page spread of “Bird’s Eye View”, the world spread out below, patchwork fields and the winding road, the car viewed straight down on the roof-rack.

At the end, there is a map, a dotted line tracing the journey from place to place and suddenly the whole thing all comes together—the same story from another perspective.

Drive would be an excellent book to take on the road (perhaps along with See You Next Year?), giving a young reader lots to look at when there’s nothing to see out the window, and perhaps inspiring her to look again and closer at the weird and wonderful world whizzing by outside.

- For more on Mad Men and children’s books, see my post, “What Sally Draper Must Have Been Reading“

May 7, 2015

Melvis and Elvis by Dennis Lee and Jeremy Tankard

It’s been over forty years since Dennis Lee invented Canadian children’s literature with the publication of Alligator Pie, following it up with Garbage Delight, The Ice Cream Store, and Jelly Belly, books that have moved seamlessly from my childhood to my children’s, so that we all know Suzy Grew a Moustache, In Kamloops, and Hugh Hugh at the age of two, who built his house in a big brown shoe. Combining the rhythms and touchstones of Mother Goose rhymes with contemporary references (and ones more charmingly dated—I’m thinking the rhyme that mentions Eatons, Simpsons and Honest Ed’s) and unabashed Canadiana and Toronto-Centrism, Dennis Lee has provided most Canadians with their poetic foundations.

It’s been over forty years since Dennis Lee invented Canadian children’s literature with the publication of Alligator Pie, following it up with Garbage Delight, The Ice Cream Store, and Jelly Belly, books that have moved seamlessly from my childhood to my children’s, so that we all know Suzy Grew a Moustache, In Kamloops, and Hugh Hugh at the age of two, who built his house in a big brown shoe. Combining the rhythms and touchstones of Mother Goose rhymes with contemporary references (and ones more charmingly dated—I’m thinking the rhyme that mentions Eatons, Simpsons and Honest Ed’s) and unabashed Canadiana and Toronto-Centrism, Dennis Lee has provided most Canadians with their poetic foundations.

And here it is: his latest collection, Melvis and Elvis, is just as good as all the rest.

How does he do it? How has he not yet run out of rhymes? How can something so simple keep seeming so fresh? How can we read a poem that begins, “Mary McGregor/ McGuffin McGee/ Went for a ride/ On the TTC.” and immediately feel as though we’ve always known the poem by heart? How “Is Your Nose Too Small?” (to the tune of “Do Your Ears Hang Low?) so perfectly hilarious? And the collection too with its mix of poems that are tender (“Sleeping With Bears”) and others slightly gross (“In Cabbagetown,” with its exploding bellies) and others naughty (one poem about a stinky friend, and another that ends, “And pounding on your head all night/ Was fun. But very impolite.”). Plus there is a poem about dinosaurs. With a poem about dinosaurs, you can never go wrong.

Dennis Lee is so respectfully and intelligently silly, and so much of the delight of his work comes from words themselves. Because is there anything more fun than rhyming pony with macaroni? Never mind that Yankee Doodle has been doing it for centuries, but in Lee’s “When I Woke Up,” one is reminded of the point of it all. And his rhymes are perfectly complemented by Jeremy Tankard’s illustrations, which seem to combine the otherworldliness (and psychedelic feel) of Frank Newfield’s illustrations for Lee’s first two children’s books, but investing them with far more kid appeal. Returning to the book over and over again, an overarching narrative becomes apparent involving Elvis the Elf and Melvis the Monster of the title, and in the book’s final poem, all the characters from the previous pages assemble to sing a song together, and we delighted in recognition.

April 30, 2015

Swimming Swimming by Gary Clement

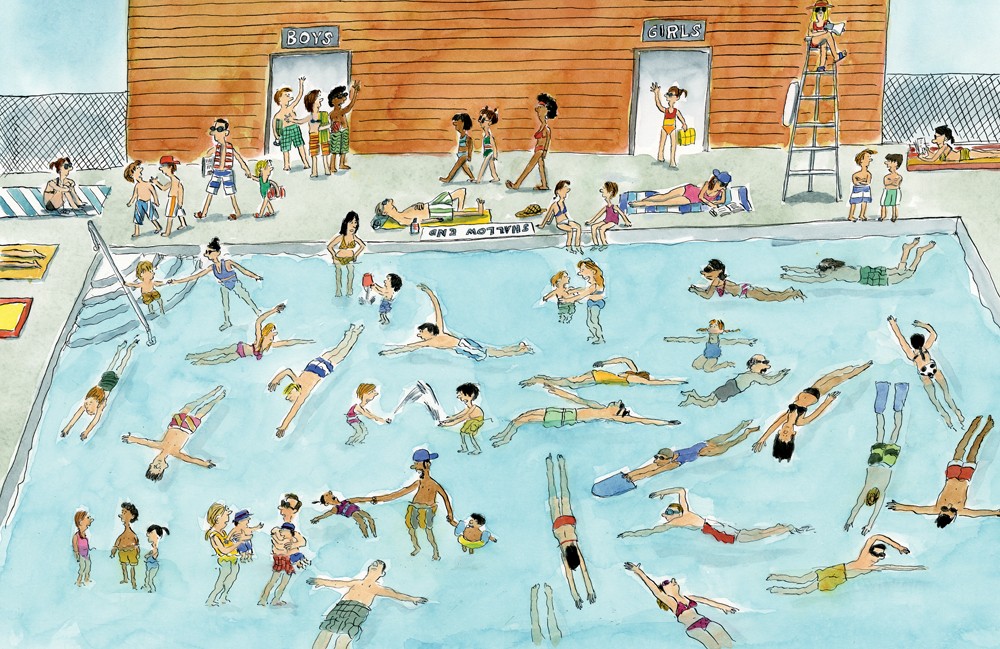

I love so many things about Gary Clement’s picture book, Swimming, Swimming, whose text is the lyrics to the traditional song that begins, “Swimming, swimming, in the swimming pool…” First, that it’s a book to be sung to, which is often engaging to readers who might not be engaged by being read to or partial to sitting still. It’s a song that’s fun to sing, even more fun to howl. Second, that it’s a summer-in-the-city book, celebrating the goodness of the public pool, an institution as vital as the library (which is saying something). In our family, we’ve become fond of swimming in the summer at the pool at Christie Pits, which is always crowded and attracts a more diverse crowd than anywhere else we ever go. There’s never any room to actually swim, I’m always irritated by teenage boys plunging in and splashing my children, and probably everyone is peeing, but friction, close quarters and pee are an inevitable part of urban life. There is beauty in the chaos, in the unabashed humanness of it all, and on hot summer days, there is no sweeter relief.

In fun, vintage style cartoon drawings (a style he used to similar effect in the nostalgia-driven Oy, Feh, So?, written by Cary Fagan), Clement depicts a summer day in the life of a swim-obsessed boy—obsession demonstrated by posters on the his walls, a diving trophy on his bureau, the fish in the bowl. And I love too this portrayal of a young person’s singular passion. The boy’s pals come by to pick him up, and together they make their way to the pool, practising their strokes along the sidewalk in a funky choreography.

They get changed, shower, arrive on deck—which is crowded with people of all ages, sizes and colours—and the song begins. It begins with the boy and his friends (the text in voice bubbles), but those around them join in the for the next line. The characters play off each other, acting out their signature strokes (and do like “fancy diving too!” in big rainbow letters, the illustration a vertical spread, as the girl of the group of friends leaps from the diving board in a loop-de-loop). And by the end of the song, everyone in the pool has stopped to face the reader and deliver the song’s final line, a very worthy question: “Oh don’t you wish you never had anything else to do?”

But alas, the pool is closing. (Or has their been a fouling?) Everybody packs up their towels and sunscreen, and makes their way for the locker room, a mirror image of the first half of the book augmented by a quick trip to the nearby ice cream truck (and this is summer-in-the-city indeed). The boy heads home, eats his dinner, feeds the fish, and collapses into bed, the goggles he’s still holding in his hand as he sleeps suggesting that tomorrow might be a day just like today was.

March 26, 2015

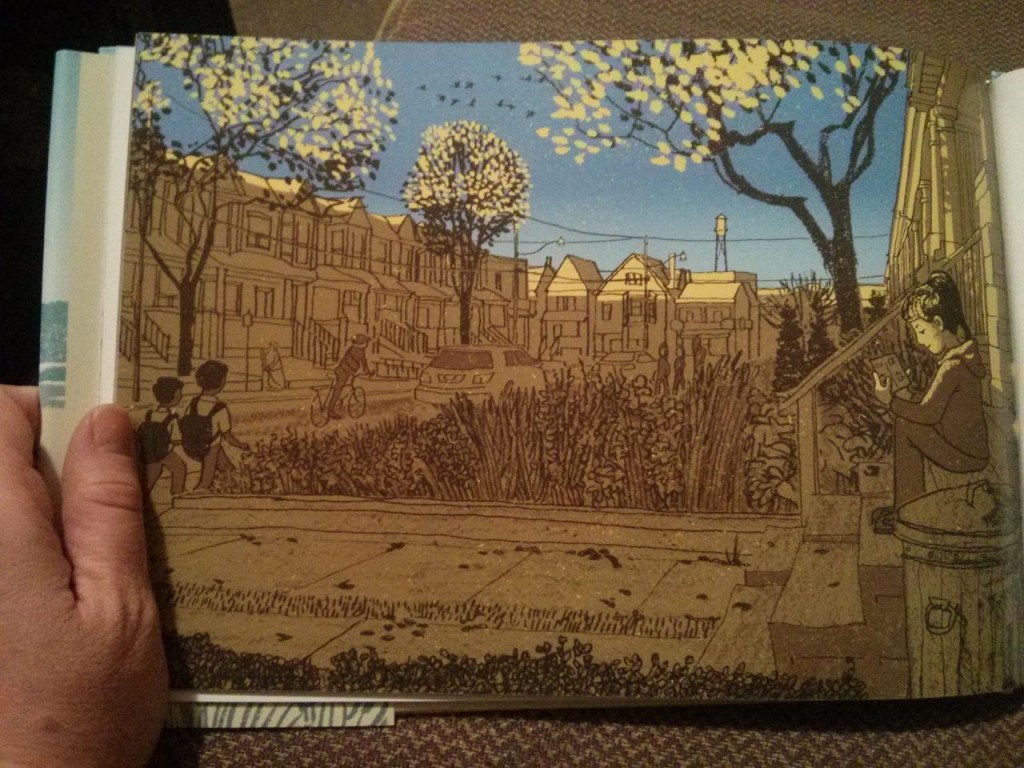

See You Next Year by Andrew Larsen and Todd Stewart

Our first Andrew Larsen book was The Imaginary Garden, which was a Best Book of the Library Haul almost 4 years ago. Since then I’ve raved about his other books, including In the Tree House and Bye Bye Butterflies, and even more important (though not more important than that he was a finalist for the TD Children’s Literature Award in November), Andrew has become my friend. We met first at the library, obviously, and because we live in the same neighbourhood, we get to walk together to school pick-up when circumstances are fortuitous. I enjoy his company immensely, and have been oh so looking forward to his new book, See You Next Summer, illustrated by Todd Stewart. And happily, it’s everything I was hoping it would be.

It’s a simple story celebrating ordinary wonders, the things we can count on, articulated in the perfect, slight-wistful child’s eye view that Larsen is becoming known for. And it’s a summer book, about a girl whose family returns to the same beachside motel for their vacations every year (“I call it our cottage. But it’s not really a cottage.”—and I appreciate that Larsen’s stories often reflect more modest economic realties, the kind we’re more familiar with in our family). It’s a place where nothing ever changes. On Sunday morning, the girl watches the tractor rake the beach, on Monday nights they go into town to the bandstand where a band plays, and on Tuesday it’s foggy, and so on. Though one thing is different this year—she’s made a new friend. They write postcards together, play in the waves, dig in the sand and roast marshmallows in a bonfire on the beach. And that’s it really. There is a twist at the end that’s really lovely, but it does nothing to counter the constancy of the narrative, to undermine the girl’s faith in sure things. Which I love—this simple celebration of rituals we build our lives around, an articulation of faith a bit less cloying than, say, The Carrot Seed. A affirmation that there are good things in the world, things to count on. Sure, the real world is going to come along and challenge the girl’s faith at some point, because that’s what growing up is, but not everything will get broken. Moreover, in this ever changing world in which we live in (to quote a Beatle), it really is the present moment that matters, and Larsen captures it splendidly—the confidence of the child who knows what she knows, whose confidence of her place in the universe is unquestioned, unshaken. It’s the sort of security that every child deserves to grow up amidst.

Todd Stevens’ illustrations are completely enthralling due his fascinating use of light. See the porch light above (with the red sunset just on the horizon), and the sunrise over the city with half the street still in shade, and elsewhere in the book, the shadow from beach umbrellas, the shadow of evening in later afternoon, how a streetlight shines through fog, the lights of the campfire, from shooting stars, the silhouette of the friend waving against the sun as the girl watches him through the back window of the car as her family begins their journey home. (On the very last page of the book, there is a light switch. I find this most significant, of course). And it occurs to me that his use of light is perfect to show the passage of time during a period in which nothing changes—Virginia Lee Burton pulled off a similar trick with The Little House. Suggesting that things are actually changing all the time, the world around us ever in flux, but that all change is part of a cycle. The images adding an additional layer of depth and poignancy to Larsen’s tale.