January 29, 2016

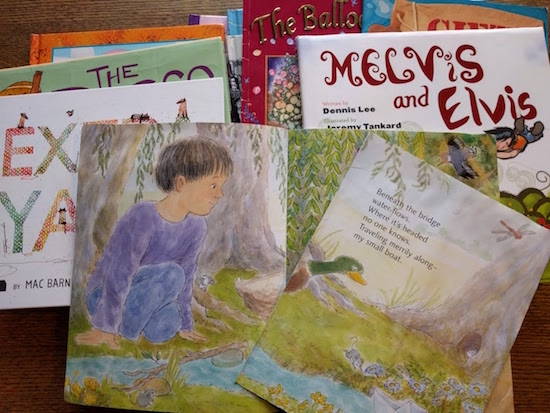

Picture Books We’ve Loved to Pieces

Wednesday was Family Literacy Day, and on 49thShelf, I wrote about the picture books our family has read to pieces. Reading with my children was been one of the most incredible parts of my life since they were born, and we’ve all come a long way since the first time I observed Family Literacy Day (which was six years ago, and I turned it into a week-long blogging extravaganza. Scroll down a bit here to se what we got up to). These days Harriet reads by herself more often than we read together, but we still read picture books every night, plus some of a chapter book—at the moment we’re doing The Borrowers Afield and it’s so perfect. Hanging out with books is my favourite way to be a family—or to be anything, for that matter…

January 22, 2016

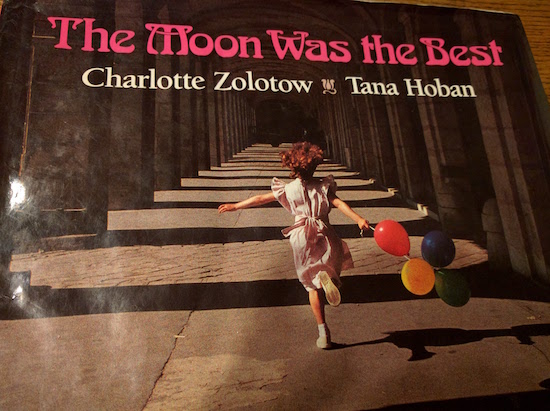

The Moon was the Best, by Charlotte Zolotow and Tana Hoban

I never knew that Charlotte Zolotow (literary legend, famous editor and author of books including William’s Doll, The Hating Book, and so so many others) worked with Tana Hoban, who was Russell’s sister and a photographer who produced beautiful children’s books throughout the 1970s and ’80s. But Harriet brought home this beautiful book from school yesterday, not a library book, a hardcover with its dust jacket intact. “What’s this?” I asked her, because she usually only brings home books about Scooby Doo. And she informed me that her teacher had loaned it to her. “I told her about the Barbados trip,” she said. “And she said I should read this.”

It’s a story about a little girl whose mother and father take a trip to Paris, and the little girl asks her mother to remember all the special things to tell her about. What the mother remembers isn’t necessarily what one would expect from a trip to Paris, but instead the memories are perfectly attuned to a child’s-eye view, gorgeously complemented by Hoban’s photographs in vivid colour.

You’ve probably heard me say before that Harriet has the most wonderful teacher, and the thing about such a statement is that it’s always been true. “The Barbados trip” is an event that looms large in Harriet’s future, our first time going away without her for a week, and while she’ll be in good care and is looking forward to many parts of having her adventures while we’re gone, she’s still nervous. Which her teacher was able to intuit, and treat with a literary salve—and what an exquisite one. I read the book twice, and its ending brought me to tears every time.

January 15, 2016

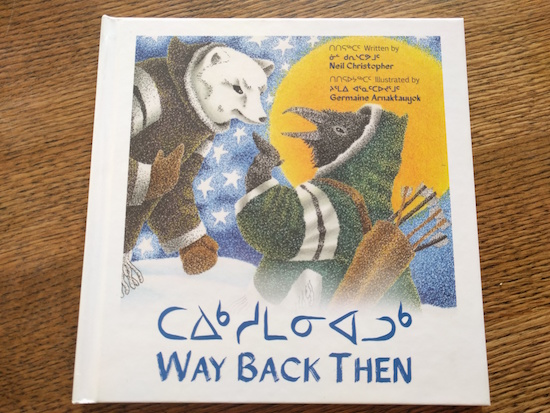

Way Back Then, by Neil Christopher and Germaine Anarktauyok

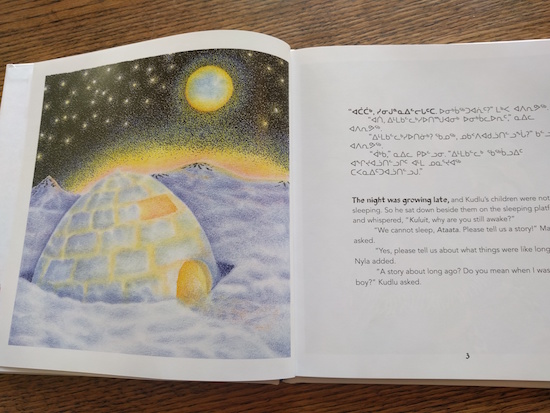

Our whole family really likes Way Back Then, by Neil Christopher and illustrated by Germaine Anarktauyok, a cozy northern story that takes place at night in a warm iglu as two children ask their father, Kudlu, to tell them stories of long ago. And not of so recently long ago either, stories of Kudlu’s boyhood, but instead tales of those times “when the mountains were giants and there was lots of magic in the world.”

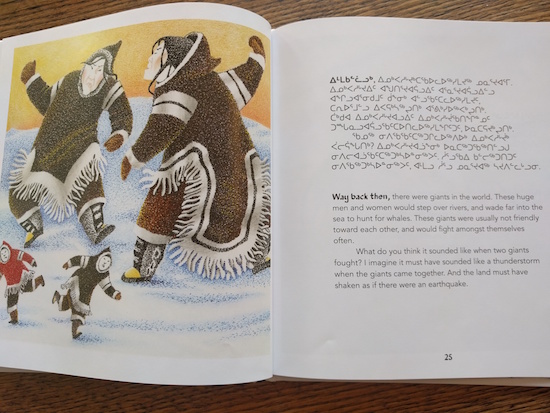

And so Kudlu proceeds to sketch out the legends he knows about why we have night and day, about how animals used to be able to remove their fur and feather like we take off our clothes, and also about how the caribou arrived when the land spirit cut a hole in the earth—but then the whole was accidentally left open and many caribou escaped and that’s why the North is filled with caribou.

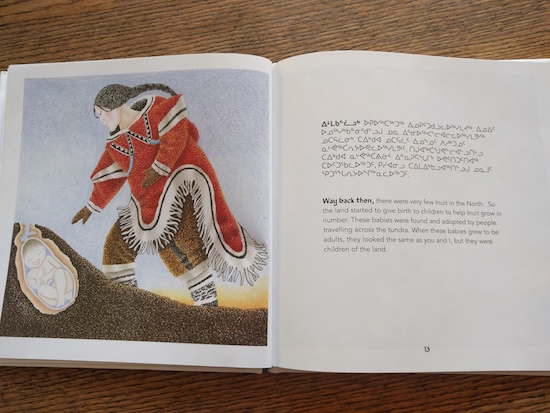

Illustrator Arnaktauyok is well-known for her paintings and prints that incorporate elements of traditional Inuit narratives. In the image above, the land is giving birth to babies in order for the Inuit to grow in number. “These babies were found and adopted by people travelling across the tundra. When these babies grew up to be adults, they looked the same as you and I, but they were children of the land.”

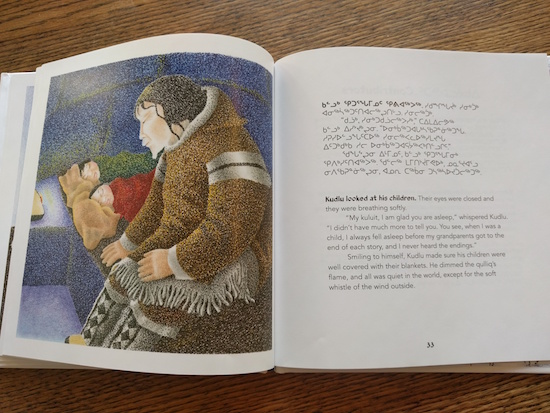

We are avid fans of fairy tales, and enthusiastically making our way through the Narnia series at the moment, which meant that these stories of tiny hunters and giants, talking animals and magic did not feel so otherworldly. The format of the stories too is engaging, the father telling these in the cozy night, children tucked up in their bed—perfect for when mine are just about to be so, even if we don’t live in an iglu ourselves. I also like the twist at the end—that Kudlu is relieved when the children finally go to sleep because he doesn’t know the endings of most of his stories, because he was always asleep himself by the time his grandparents got to those parts.

Inhabit Media is the only Inuit-owned publishing company in Canada’s north and they’ve become well established as makers of beautiful award-winning books that also serve to preserve Inuit culture. Written in both English and Inuktitut, the book also includes an Inuktitut pronunciation guide for terms that appear in the former—ataata (“a-ta-ta”) for Father; kuluit (“koo-loo-eet”), a term of endearment meaning “dear ones.”

And check out the caribou endpapers—this is a great book from start to finish.

January 8, 2016

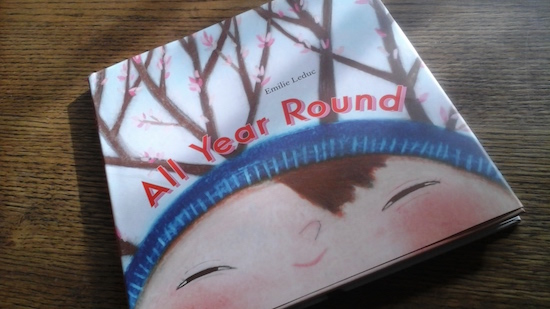

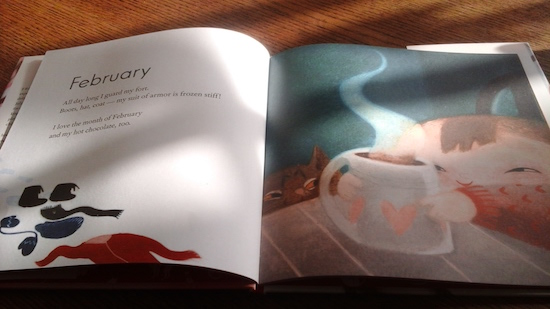

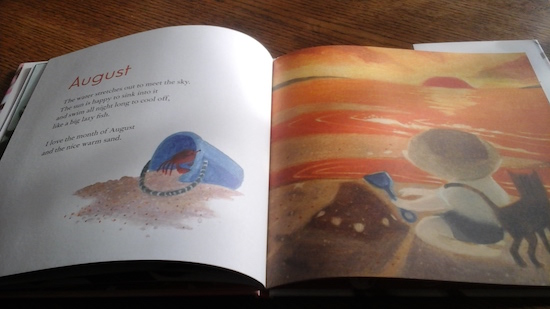

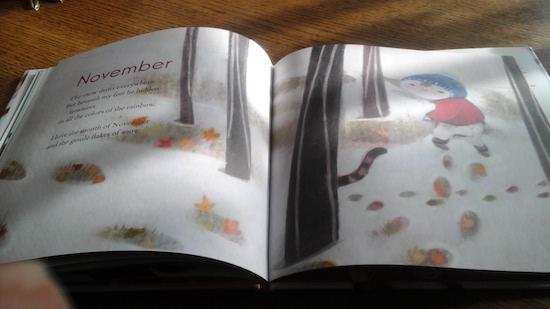

All Year Round, by Emilie Leduc

The new year is a perfect occasion to pick up All Year Round, written and illustrated by Emilie Leduc and translated from French by Shelley Tanaka. While it’s a truth universally known that there is no months-of-the-year book as perfect as Maurice Sendak’s Chicken Soup With Rice, it’s nice to also have another book that actually makes sense. Even if it fails to contain the line, “Whoopy once! Whoopy twice!”—my one criticism of this book. And most books, actually.

Each month includes a prose poem and beautiful celebratory illustration from a child’s point of view. Plus, a glimpse of a cat called Clementine, much to any young reader’s delight.

Every month and every season contains something wondrous, and that each month hinges on a non-secular occasion offers this book a perfect universality.

This book is a story about the rhythms of our world and of our lives—just as good as riding a crocodile down the chicken soupy Nile!

November 19, 2015

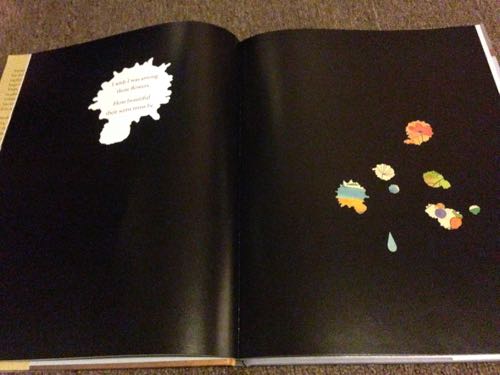

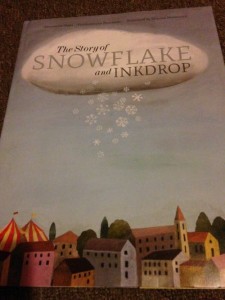

The Story of Snowflake and Inkdrop

The Story of Snowflake and Inkdrop is written by Pierdomenico Baccalario and Alessandro Gatti, illustrated by Simona Mulazzani, and translated from Italian by Brenda Porster. It’s a gorgeously illustrated picture book about yearning, desire, and storytelling, with beautiful intricate die cuts that make it a book that might be better be kept up on a hight shelf, and perhaps best suited for grown-up picture book lovers. Although my children, with their grubby little fingers, like the book as much as I do, and are as adept at getting lost in the illustrations, and perhaps even better at picking out its perfect details, at noticing things. And there is a lot to notice here, in a book about tiny particles and what it means to be part of something larger than oneself. And also about what it means to see the world and want to be a part of it, and the amazing, serendipitous way that this (that love!?) can happen.

The Story of Snowflake and Inkdrop is written by Pierdomenico Baccalario and Alessandro Gatti, illustrated by Simona Mulazzani, and translated from Italian by Brenda Porster. It’s a gorgeously illustrated picture book about yearning, desire, and storytelling, with beautiful intricate die cuts that make it a book that might be better be kept up on a hight shelf, and perhaps best suited for grown-up picture book lovers. Although my children, with their grubby little fingers, like the book as much as I do, and are as adept at getting lost in the illustrations, and perhaps even better at picking out its perfect details, at noticing things. And there is a lot to notice here, in a book about tiny particles and what it means to be part of something larger than oneself. And also about what it means to see the world and want to be a part of it, and the amazing, serendipitous way that this (that love!?) can happen.

At first, this is the story of some wind and a snowflake drifting over the rooftops of a European town. The snowflake, we’re told, has been travelling for a long time. He feels, however, that he’s finally on the cusp of arriving somewhere, and the world below is glimpsed through the snowflake’s crystals, revealed altogether when the page is turned: we see a city street in one image, a circus in another, and then children playing in a park as the snow begins to accumulate.

In none of these scenes does the snowflake fall, however, and he begins to despair that he ever will… When he sees a tiny ink drop flying resolutely toward him, and the snowflake is overwhelmed by the desire to hug it tight. BUT WAIT!

Turning the book around and starting from the other side, we encounter that storm from an altogether new perspective. A single drop in a bottle of ink watching the wind rattling the world outside.

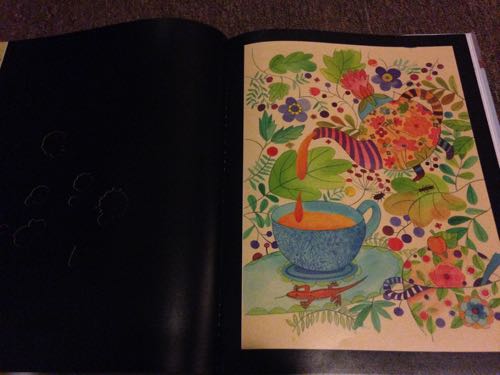

Although the Inkdrop has her own concerns—for days, she’s been waiting for her artist to finally carry her to one of his paintings. Her longing is intensified as a gust of wind from the window blows the paintings around the studio, so that they “flew up, dancing in front of Inkdrop like so many dreams.”

She sees each painting, and wishes deeply to be a part of the scene.

And yes, it is a picture of a teapot. Naturally, we are delighted. We see also a portrait, a bucolic scene. (Clearly this is an artist with a diverse set of approaches!)

When the wind blows so strongly again, unleashing a chain reaction that sends the ink bottle tilting, Inkdrop herself flying out of the window. And then we’re back at the moment we’ve seen before, the ink drop and the snowflake heading for each other in a dazzling cataclysm.

And both books end in the same place, the two parts coming together to have their stories blend, this final image testament to the beauty of contrast.

Truthfully, I am not entirely ensure what the endings means, the snowflake and the inkdrop landing in an embrace “that lasted forever.” When one considers physics, it does not seem entirely plausible, and there is the matter of the inkdrop in the jar—what then of the rest of the ink? Where did one drop end and another begin? And why is the artist so scattered in his style—is he perhaps a forger, I wonder? (Although he looks quite innocent and rosy-cheeked when we spy him out buying a baguette.) One suspects, however, that physics aren’t quite the object of the book, except perhaps those involves in the die-cutting process. For The Story of Snowflake and the Inkdrop is to be looked at and admired and even roughed up a bit by those aforementioned grubby hands, and perhaps this one is the single way that the book should be torn apart at all.

November 13, 2015

The TD Grade One Giveaway!

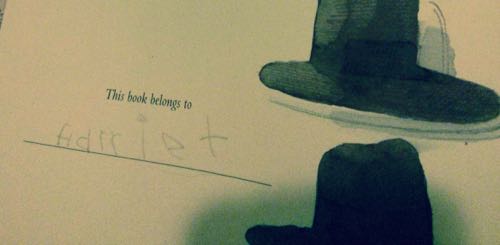

On Monday, Harriet pulled Mr. Zinger’s Hat, the 2015 TD Grade One Giveaway, out of her backpack. And I was confused. “How did you get that?” I asked her. A few seconds of discombobulation before the obvious point dawned on me: that Harriet is in grade one, receiving the book with other six-year-olds across the country. Literally, I’d been waiting years for this.

They didn’t have the TD Grade One Giveaway when I was grade one, but I learned about the program first when I started working for 49thShelf.com, and was invited to an event promoting the campaign. This was in 2011, when the giveaway pick was Gifts, by Jo-Ellen Bogart and Barbara Reid. (I wrote about it here.) And in the years since, I’ve been kept in the loop, receiving copies of the books at the TD Children’s Literature Awards (which is the one gala per year I get invited to…)

In a house like ours, the arrival of a brand new book is not such a momentous occasion…or so I thought. But Harriet bringing home a book that was hers alone, so much hers that she’d already written her name in the space allotted on the inside cover, turned out to be really, really exciting. And I can’t imagine what it might mean to a kid who doesn’t have access to all the books that Harriet does, to have a book that’s all their own. Although I can imagine what it’s like for any family to have the pleasure of a brand new book to read together—it’s one of the best things ever. I also appreciate how notes at the back of the book include a listing of every single award-winning Canadian book from the previous year, which is whole words to explore the next time that family visits the library, and another excellent example of one book leading to another.

Yesterday it was reported in the Toronto Star that students in York Region won’t be receiving Mr. Zinger’s Hat due to rules against corporate sponsorship in schools. And while such a stance is admirable, and while I do wonder why the banks have so much money that nothing seems to happen without them, I know that TD has a long, established and admirable record of supporting early literacy. In addition to the Grade One Giveaway, they sponsor initiatives including summer reading programs at libraries throughout the country, TD Children’s Book Week (which sends authors to school across Canada every spring), and the nation’s biggest children’s lit prize. (Also, the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Prize is named for Marilyn Baillie, Canadian children’s author and wife of former TD Chairman A. Charles Baillie—just another connection).

Upon reflection, it occurs to me that the preceding paragraph is the most corporate shilly collection of sentences I’ve ever written. Do I need to point out then that I’ve not received compensation for it from TD or anyone (though if they’d like to send me funds, I’d be willing to entertain all possibilities)? But I suppose it’s just I really believe in a program like this, one that makes great books available to everyone. And I love the idea of kids across the country united by the power of a story.

November 6, 2015

Elephant Journey The True Story of Three Zoo Elephants and their Rescue from Captivity, by Rob Laidlaw and Brian Deines

Elephant Journey: The True Story of Three Zoo Elephants and their Rescue from Captivity, by Rob Laidlaw and Brian Deines, is a fantastic non-fiction book that uses the power of narrative (and the award-winning Deines’ gorgeous illustrations) to bring complex issues of animal protection to life. It’s the story of the two elephants from the Toronto Zoo who were brought there from African in the 1970s, when our understanding of the culture and purpose of zoos was very different, and one more who was born in captivity, all of whom failed to thrive in a northern climate so unsuited to their species. (For more about the zoo and elephants, read Nicholas Hune-Brown’s 2010 article, “What the Elephants Know”.)

After much political wrangling (which Laidlaw mercifully omits from his version of the tale), it was decided that the three elephants were to be moved to an animal sanctuary in California. And that amazing journey is the focus of this story, how the elephants were made accustomed to their crates, which where then picked up by giant cranes and loaded onto flatbed trailers towed by trucks. (And I love the illustration of the truck, being accompanied by a police car, headlights, streetlights, and flashing lights in the night; Deines is good at drawing trucks, one of which was a focus of Number 21, by Nancy Hundal, another book of his that we’ve enjoyed.)

The elephants make their way past surprised border guards, through the American midwest, and up and down the mountains in Utah and Nevada, where the brakes on one truck begin to overheat, but all is well after the driver douses them with water. And then the elephants arrive, become comfortable enough to leave their crates, and begin to acquaint themselves with their new neighbours, new surroundings and new lives.

Four pages of photographs, fact boxes and additional text add context and background to Laidlaw’s story, though the book stands well enough on its own without it. It’s a harrowing story with a most hopeful ending, and will make a definite impression on readers of all ages.

October 30, 2015

Missing Nimama, by Melanie Florence and François Thisdale

It’s not my usual practice here to write about a picture book that I haven’t read with my children, but Missing Nimama, by Melanie Florence and François Thisdale, is not your usual picture book. And I didn’t read it with my children not because they don’t know about Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Girls and Women—indeed, my 6 year old does know about this terrible part of our country’s colonial legacy, a legacy that’s lasted right up to this exact second—but because she told me she didn’t want to read a story that was sad. And neither did I, truthfully, to have to give voice to this story’s achingly, awful, beautiful words: the words of a mother who has been lost to her daughter but watches over her still, and the words of a daughter who has to grow up without the mother who loves her oh so much.

Stories of children who’ve lost their mothers are perhaps the most unbearable thing I can contemplate. So I don’t, usually. But in the case of Missing Nimama, I was compelled to read on, spurred on by Thisdale’s gorgeous dreamlike illustrations (which are similar in effect to his work in the acclaimed The Stamp Collector). I was also drawn by the story, written by Cree writer and journalist Florence. Her young character, Kateri, is raised by her loving maternal grandmother, who tells her that her mother is lost:

‘”If she’s lost, let’s just go and find her.”

Nohkom smooths my hair, soft and dark

as a raven’s wing.

Parts it. Braids it. Ties it with a red ribbon,

My mother’s favourite colour.

“She’s one of the lost women, kamamakos.”

She calls me “little butterfly.” Just like my nimama did.

Before she got lost.’

And then we hear nimama’s voice: “Taken. Taken from my home. Taken from my family. Taken from my daughter. My kamamakos. My beautiful little butterfly. I fought so hard to get back to you, Kateri. I wish I could tell you that. And when I couldn’t fight anymore, I closed my eyes. And saw your beautiful face.”

We see Kateri growing up, thriving under the loving care of her grandmother, and under the proud watchful eye of her mother. We see her grappling with her loss and grief, learning about her culture and traditions, growing up and finding her way in the world. And the heartbreaking sadness of the story is balanced by Kateri’s success in her life—the stability she finds as she grows older, gets married, has a child of her own. A stability that is against the odds, perhaps, and I think about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in connection with the history of Residential Schools and how many social problems in First Nations communities are results from over a century of cultural genocide. Not to mention the much more direct instances of government-sanctioned violence against Indigenous women in Canada.

I think of all these children who’ve lost their moms.

I don’t think that children like mine are necessarily who this picture book is meant for, not right at this moment in time, perhaps. For the far too many children for whom this story is close to home, however, I can’t imagine how powerful it would be to see one’s own experience reflected in a story like this, Kateri’s own story an inspiring example of the path a life can take, even one that begins with incalculable loss and trauma. (Which is not to say that this isn’t an important story for anyone—it’s such a visually compelling book that I’d like to keep it around, have my children leaf through, and become familiar with. We will definitely read it together. We’ll just have to ease our way into it…)

But then, someone might ask, why is it a picture book after all? Surely a book with such subject matter should be geared toward older readers? Should be a chapter book, at least? To which I respond that picture books have nothing to do with age. That grief and trauma don’t have a minimum age requirement either, sadly. That picture books allow this story to be accessible to all kinds of readers (and, remarkably, like all books from Clockwise Press, this one is printed in a “dyslexia-friendly” typeface). And most of all, that this story works because it’s a picture book, because of the marriage of words and stories, and how the respective voices of mother and daughter can exist together, even if apart, on the page.

Missing Nimama is a mourning song, but also a call to action. Near the end of the story, Kateri attends a public vigil for missing and murder aboriginal women: “Stolen sisters. I hold my own sign. My own lost loved one.” And the book’s final page contains quotations by family members of murdered women, from the UN Report which dictates that “Canada must take measures to establish a National Public Inquiry into cases of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls.” And our soon to be ex-Prime Minister’s infamous shameful view on the subject: “It isn’t really high on our radar, to be honest.”

The numbers are important, inarguable. “A total of 1181 Indigenous women and girls have been murdered or went missing between 1980 and 2012.”

But it’s going to be stories—like that this one—that make the difference if we’re to give all of our daughters a chance to live in a better world.

October 23, 2015

The Ghosts Go Spooking, by Chrissy Bozik and Patricia Storms

This week our family has been having fun with The Ghosts Go Spooking, a new picture book written by Chrissy Bozik and illustrated by my friend, Patricia Storms. Sung to the tune of The Ants Go Marching, the story traces the antics as a group of friendly ghosts make the most of Halloween night on their way to a costume party at a haunted house. A nice touch is that the ghosts themselves are costumed—as a clown, a witch, a cowboy. As as they go, one-by-one, two-by-two, etc., one of them (a different one every time—the scary one, the silly one, the wiggly one) stops and does a variety of things—knockings on a door, does a jive, does some tricks.

The story is more fun than scary, which is a good thing with our crowd, and my kids like the mischief the ghosts get up to, their amusing extra-textual dialogue in the illustrations: “Better than a rabbit,” exclaims the Bunny-hopping ghost when “the clever one” conjures bats from his hat. Momentum builds as the ghosts eventually end up spooking ten-by-ten, arriving at their party to find a horn-playing werewolf and a vampire on the double-bass, spooky rock-and-rolling against an enormous yellow moon. No doubt this is a party that will go one well into the night.

Boo boo boo…

October 9, 2015

Written and Drawn by Henrietta, A Toon Book by Liniers

We are in love, besotted, absolutely gaga. I first heard tell of Henrietta—a small brilliant and bookish girl who appears in the Macanudo comics by Argentine artist Liniers—when “Henrietta’s Reading Adventures” appeared in The New Yorker. Then Dan Wagstaff informed me that a Henrietta book was forthcoming from TOON Books, which we’re huge fans of. And that book is Written and Drawn by Henrietta, fun, inspiring and amazingly terrific. We read it together over dinner last night, and just now I had to go retrieve it from Harriet’s bed.

We are in love, besotted, absolutely gaga. I first heard tell of Henrietta—a small brilliant and bookish girl who appears in the Macanudo comics by Argentine artist Liniers—when “Henrietta’s Reading Adventures” appeared in The New Yorker. Then Dan Wagstaff informed me that a Henrietta book was forthcoming from TOON Books, which we’re huge fans of. And that book is Written and Drawn by Henrietta, fun, inspiring and amazingly terrific. We read it together over dinner last night, and just now I had to go retrieve it from Harriet’s bed.

Written and Drawn by Henrietta is a story about the pleasures and frustrations of the creative process. Young readers will be inspired by Henrietta’s creation to make an attempt at their own literary masterpiece (and won’t be intimidated either, with Liniers’ rudimentary-looking Henrietta-style). They will also benefit from practical advice Henrietta offers along the way:

Creating art is not without its challenges and pitfalls, and Henrietta contemplates these as well.

But the narrative is driven primarily by her wonder and her excitement at the story she is creating (“I’m drawing really fast because I want to see what happens next…”) and the reader will be inspired to begin her own creation on Henrietta’s coattails.

…Or at least I’d like to meet the kid who wasn’t.