July 29, 2016

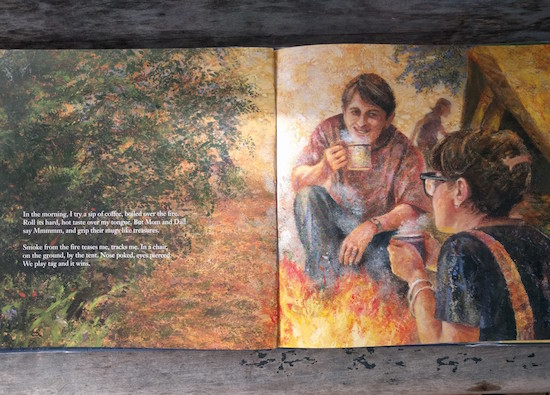

Camping, by Nancy Hundal and Brian Deines

Iris picked this book from a display at Lillian H. Smith Library yesterday, Camping, by Nancy Hundal and Brian Deines, published in 2002. It’s about a family in which nobody is really excited about the prospect of camping, but money is tight and camping is cheap, and throughout the story, they all discover a love of camping. Their experience differs from ours because a) I don’t find camping all that cheap (every year I think we have all the equipment we could possibly need, and then there’s always something more) and b) we are all of us in every family very excited about the prospect of camping. This book has helped us be even more so. (I love the page with the spread of stars the best. The night sky is definitely one of my favourite parts of camping. That, and reading ARC’s of new Louise Penny novels, which seems to be a tradition for me.)

This particular page is the one I love the best though, because indeed there is something about morning campfires and camping coffee and tea. And for sure, we grip our mugs like they’re treasures. Aren’t they though?

July 22, 2016

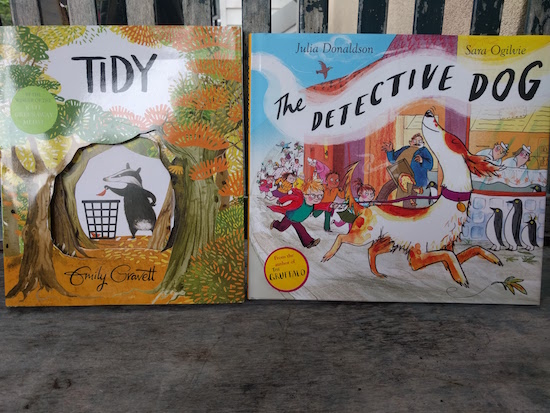

New books by Julia Donaldson and Emily Gravett

How exactly does a person follow up a success like The Gruffalo? For some authors, the pressure would be paralyzing, but not so for Julia Donaldson, who has published more books than I’ve had hot dinners. (I actually suspect Julia Donaldson has never ever been paralyzed. I once saw her live [I am THAT cool] and she incorporates a whole musical thing into her act but [and here’s the rub]: she can’t actually sing. Not on key, at least. And she doesn’t care and sings anyway, and the children loved her and so did I and it all was wonderful.)

Donaldson has worked with different illustrators to dramatically different effect, and certainly some of her books are more compelling than others (although maybe you’ve got to hear them set to music), but still, she’s got a formula. You know what you’re getting. Rhyming couplets, a bit of drama, and something heartwarming at the end. Sometimes a little light on plot and a rhyme that gets a teeny bit awkward, but it’s all in how you read it. It’s in the rhythm. She knows what she’s doing and she does it very well.

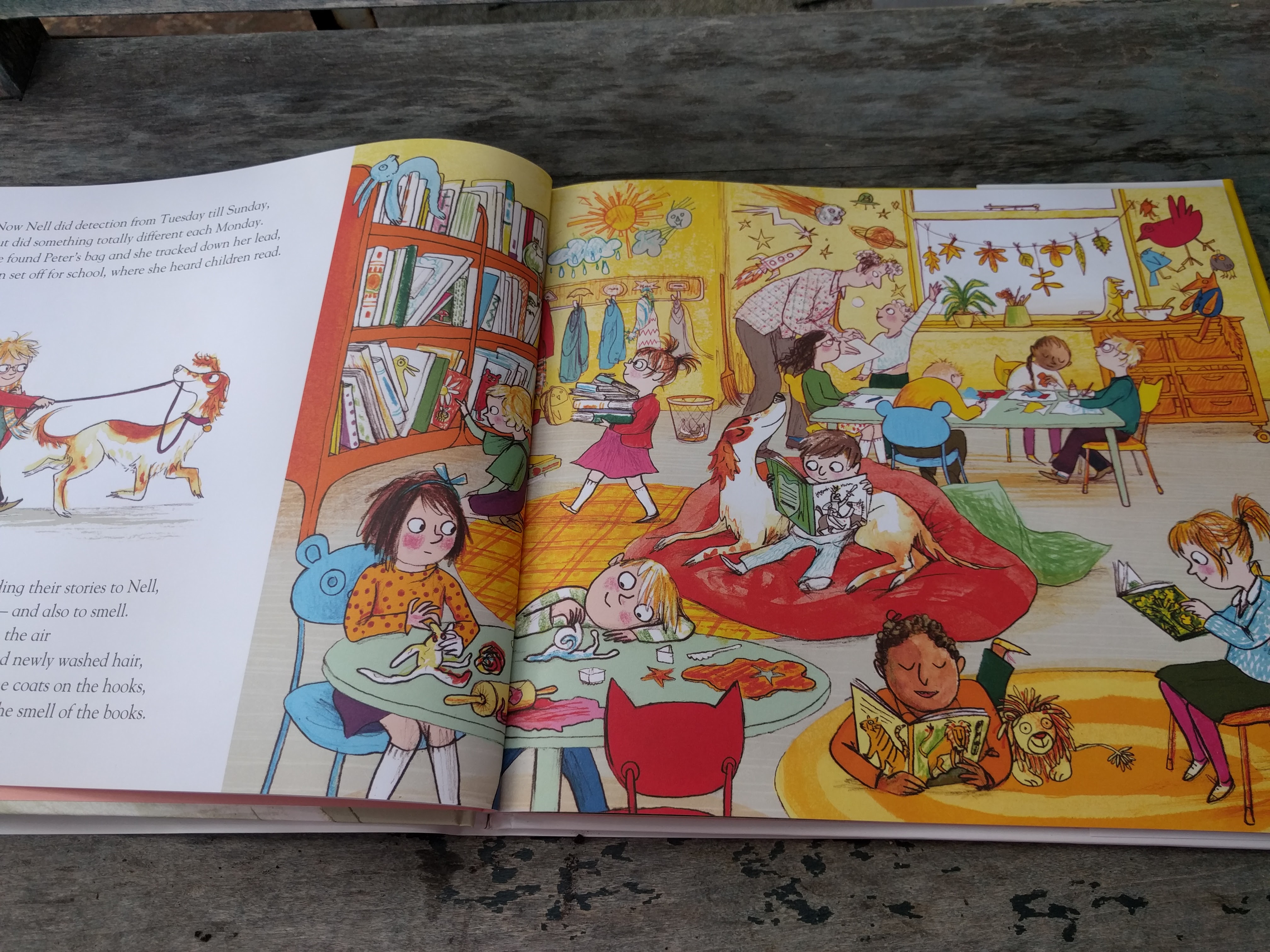

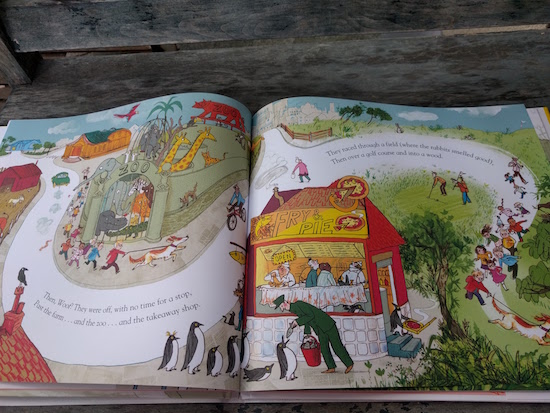

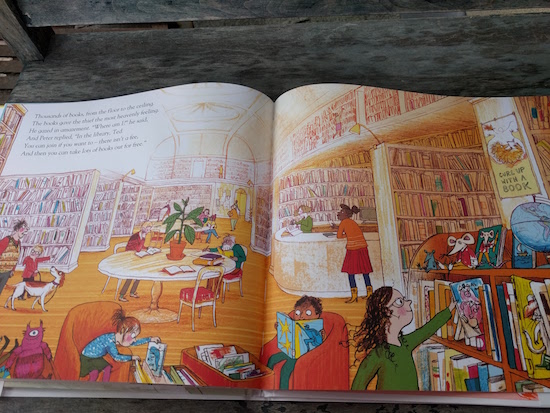

The narrative of her latest, The Detective Dog, starts off as a bit of a stretch. Detective Dog Nell, with her famous sniffer, solves crimes six days a week (“Who did the poo on the new gravel path?/How did the spider get into the bath?), and on the other day goes to school with her owner, Peter, and has the children in his class read to her (although reading dogs are a thing—did you know that?) Nell likes visiting the school, where “the best smell of all was the smell of the books.

Having a Detective Dog moonlight as a Reading Therapy Pup comes in handy, however, one day when Nell and the children arrive at school to find all the books in the classroom have been stolen. Immediately Nell is on the case and traces the thief across town to a shed where the thief (who, naturally, is called Ted) confesses that he just wanted to read them, and he was only borrowing the books. Which reminds everybody of a place where everybody can go to borrow books, no thievery necessary, which is, of course, the library, and this fun but crowded book culminates quite nicely in a celebration of public libraries, which bring literacy to everyone. And who’d argue with that?

In my mind, Julia Donaldson and Emily Gravett are two of a kind, rhyming coupleteers who arrived in my life around the same time, with the birth of my first daughter. (They have one book together, actually: Cave Baby). I think I first encountered Gravett with the wonderful Monkey and Me, which I like so much that we have it out of the library as I write this. And also Orange Pear Apple Bear and Wolf Won’t Bite and The Rabbit Problem, and so many more. An illustrator with a keen sense of book design, Gravett is ambitious and pushes her own limits and also those of the book itself. Case in point, in her latest book, Tidy, the info on the copyright page is being sucked up into a vacuum. Oh, and the dust jacket has images on both the front and back, both of which are different from the image on the book itself—there is so much richness here, attention to detail, treasures to discover for readers who bother to look close enough.

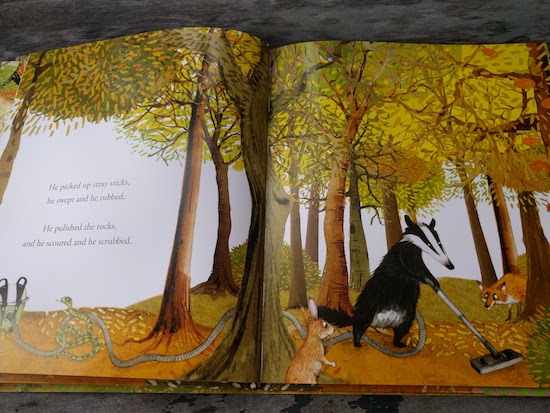

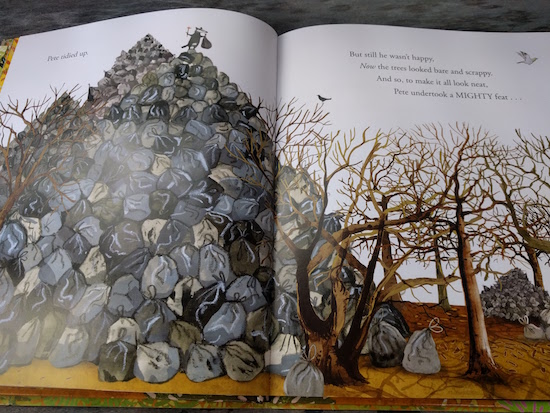

Tidy is the story of a clean-freak badger who likes to keep the forest tidy, much to the chagrin of his friends. “He picked up stray sticks, he swept and he rubbed. He polished the rocks and he scoured and scrubbed.” And when the autumn leaves fell, well, he got busy, bagging every one of them.

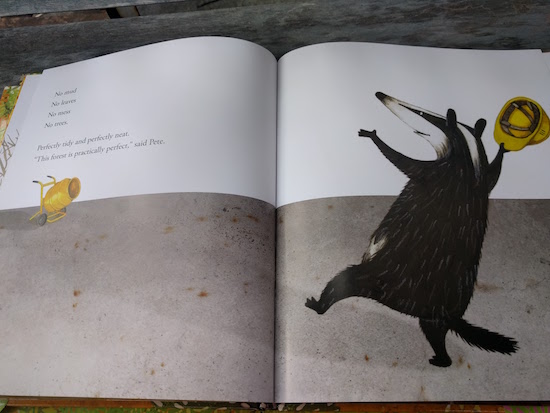

This is one of those stories about one thing leading to another with unintended consequences, cute with an environmental bent. He decides to clean up the scrappy trees by pulling them out of the ground, but then without trees the ground gets muddy, and so he covers everything in concrete, which is totally neat and totally fine…except there is nothing for him to eat and he’s mistakenly blocked up the door to his burrow.

A happy ending is delivered with the help of a jackhammer, which breaks up the concrete, and the badger gets those trees planted again, and he tries to learn his lesson, to tame his over-tidy ways, and he is mostly successful—the story ends with a bunch of ants throwing all of his cleaning supplies into a bin marked “Keep Your Forest Clean.”

As ever, the lesson is: with Emily Gravett and Julia Donaldson you pretty much just can’t go wrong.

July 15, 2016

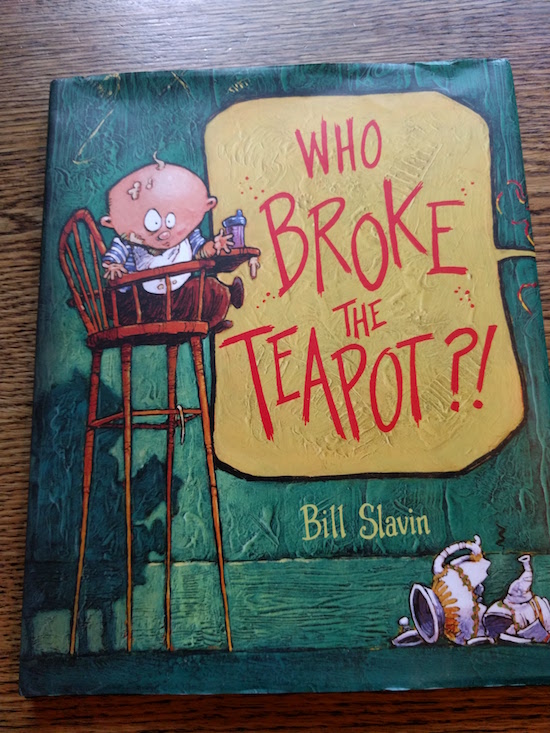

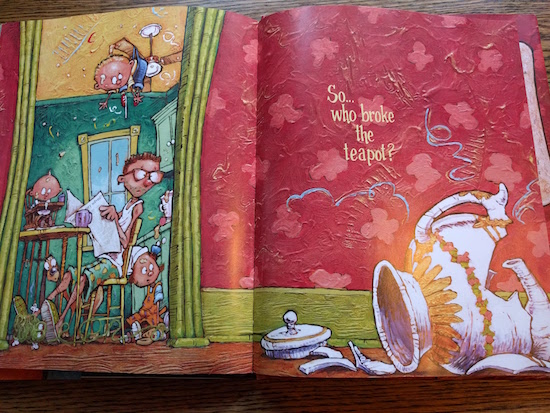

Who Broke The Teapot?, by Bill Slavin

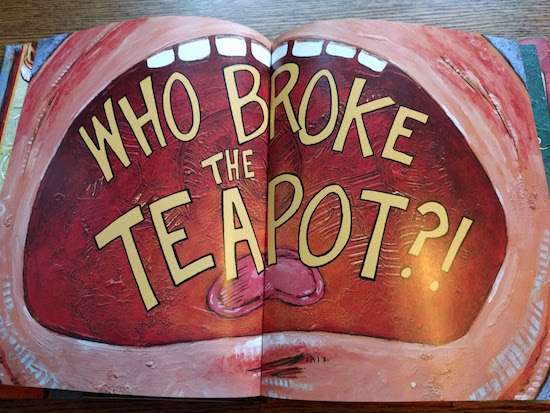

To those who might wonder how a broken teapot could sustain narrative enough to fill an entire book, I will raise the matter of my polka-dotted teapot which got smashed last year on Christmas Day and had me sulking right up until New Years. And so when I heard about Bill Slavin’s new picture book, Who Broke the Teapot?, I did wonder if the plot had been stolen from my life.

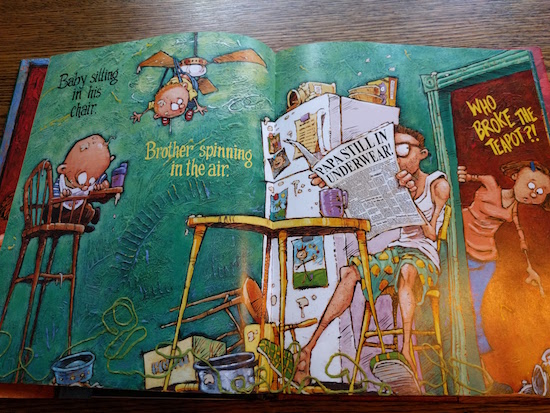

Mother’s beloved teapot is toppled and smashed, and it’s not immediately clear who committed the crime. In our house it was Papa who did it, and he was actually wearing pants, but still, he ‘fessed up right away. Circumstances in Slavin’s book, however, are far more mysterious. The teapot is smashed and the house is in chaos, and what actually happened is hard to discern. And so the set-up of the story is picture book whodunnit. It’s up to the reader to put the pieces together and discover what actually occurred.

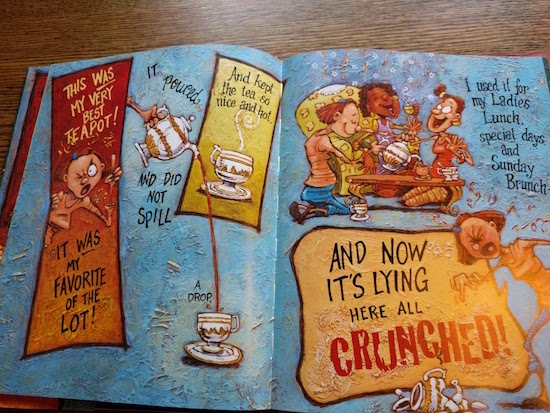

And my sympathies were indeed with the mother, even in her unattractive irateness. I’ve been there, so I totally get it, but even if you haven’t, you can understand what it would feel like to lose your very favourite teapot, your favourite of the lot. Which poured but did not spill a drop. And certainly, such teapots are rare and precious objects, the sort you encounter a handful of times in the span of a life. To find one in pieces on the floor would be devastating.

Of course, I like the book because it is basically a memoir about my life, and I identify with the protagonist, and it is hugely affirming to see my experiences represented in literature. But is that enough to sustain narrative enough to fill an entire book? Is it possible to love this book if you are not a 37 year old teapot enthusiast who weathered a similar tragedy just mere months ago?

And the answer is: YES. My children love this book, and not just because it mentions underwear (although they do love that part—as well as the part where the baby says, “Babadoo.”) Three-year-old Iris can now recite the book in its entirety, and it’s only lived in our house for a week, so it’s safe to say it’s made an impression. The rhyming text is fun and playful, the illustrations are full of action and detail, and the surprise ending is spot-on. And also just a tiny bit ambiguous, which means you get to go back to the beginning and read it again.

July 8, 2016

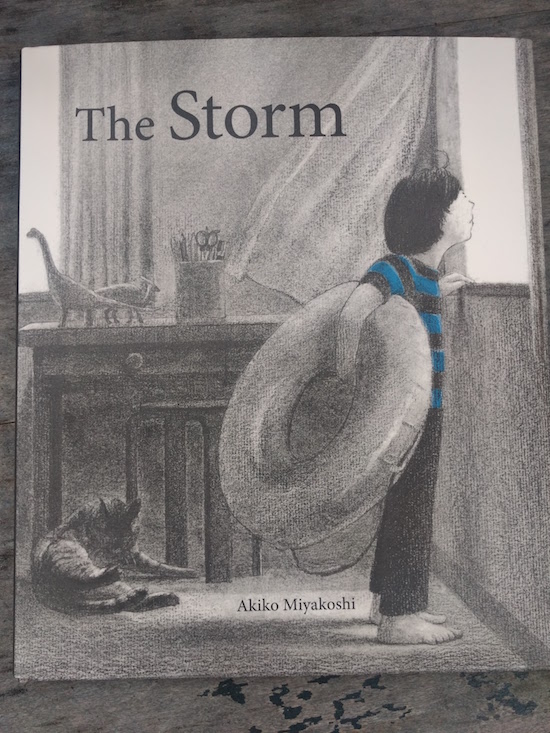

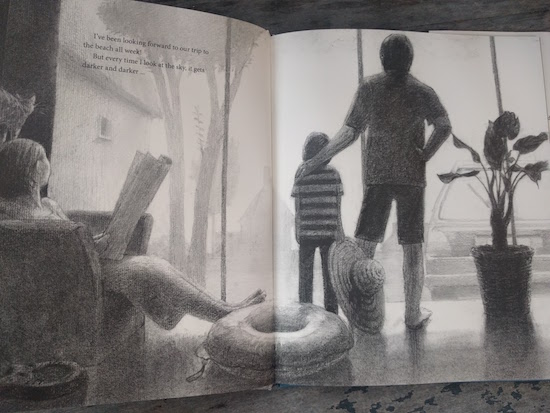

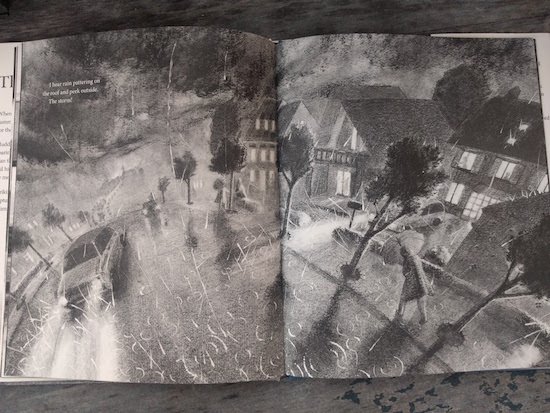

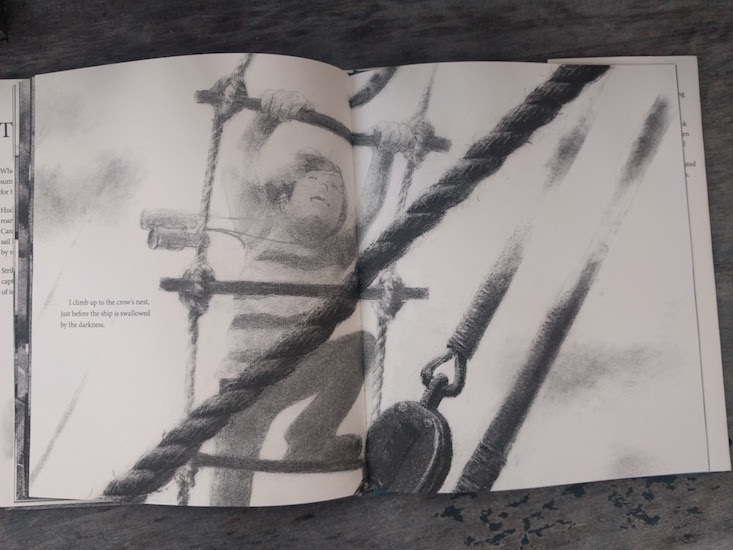

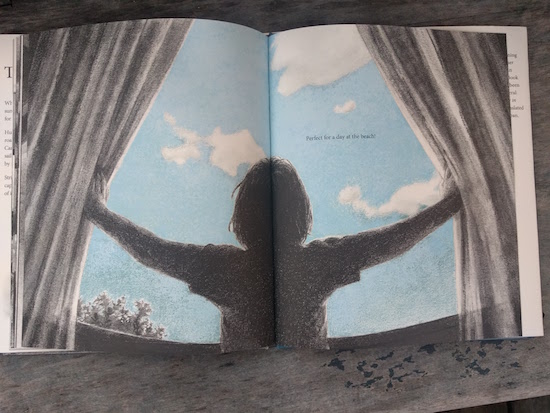

The Storm, by Akiko Miyakoshi

It’s summer, hot and sweltering, not necessarily sultry like the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, but the cicadas are buzzing in the trees outside my house, and it is that certain heightendness to everything that moved me to pick up The Storm, by Akiko Miyakoshi, again. A quiet, simple story, or at least I thought so when I first read it a few months back, when the season outside was only spring. But then yesterday we had a thunderstorm, four days of intense heat broken for a little while with thunder and rain, all that tension in the air. And it was here where I realized that The Storm is not as simple as it initially seems, that the tension is the point, that the story is infused with atmosphere.

The Storm is actually Miyakoshi’s first book, but her second to be translated into English after The Tea Party in the Woods, which gained remarkable acclaim. I haven’t written about that book yet, but I really like it, what with tea parties, forest friends, mismatched slices of pie, and a brave girl with a job to do. The Tea Party is a fairy tale, whereas The Storm just skims the border of one, but both books feature Miyakoshi’s remarkable charcoal illustrations, which mingles abstraction with exquisite detail, and don’t you find that literal shadows add so much depth to a book, a invitation to look closer?

I realized yesterday that The Storm is a perfect summer book, the clash of expectations with reality, extreme weather and flights of imagination. The narrator of the story is looking forward to a trip to the beach the next day, and worried about weather warnings, a darkening sky. The phrase “batten down the hatches” comes to mind, as his parents bring inside their pot plants and secure their shutters, and it brought to mind typhoon season during the time we lived in Japan, those massive storms that shook earthquake-proof buildings that were conditioned to sway in the breeze. They made yesterday’s thunderstorm here in Toronto basically on par with a sun shower.

Afraid of the weather and dismayed by the prospect of his beach day ruined, the boy goes to bed, hides under his covers (presumably his house is air-conditioned. I will not hide under my covers until at least mid-September, and the box fan doesn’t cut it) and spends the night dreaming of controlling a massive airship with propellers that can blow the storm away. Until: “At last, the storm passes, and I sail into clear skies.”

In the morning he awakens to blue skies, and it’s not immediately clear to the reader that the boy was not agent of this miracle after all. Which makes this an excellent story about optimism, the power of imagination, and a reminder that if we just hold on, clear skies will come around again.

June 10, 2016

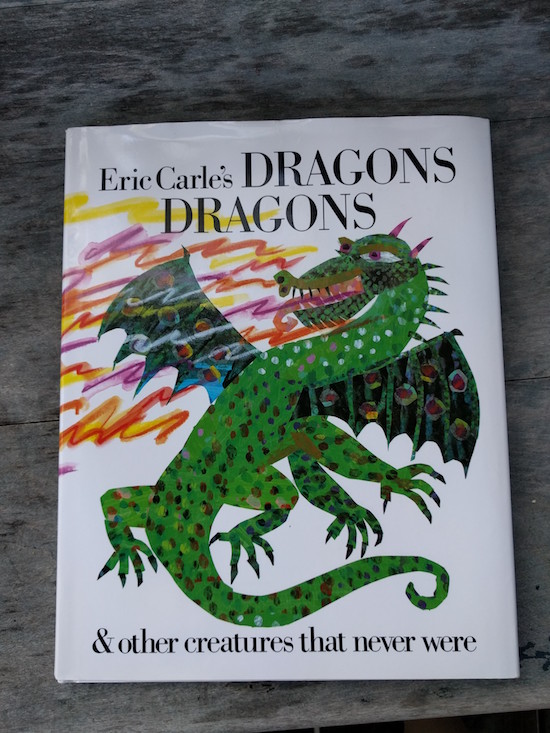

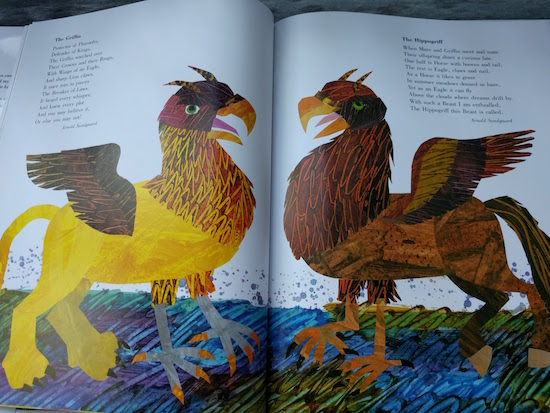

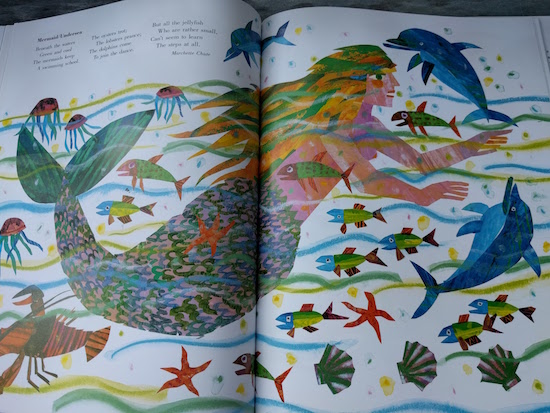

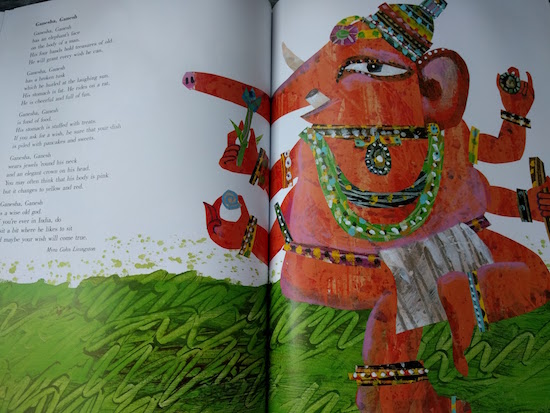

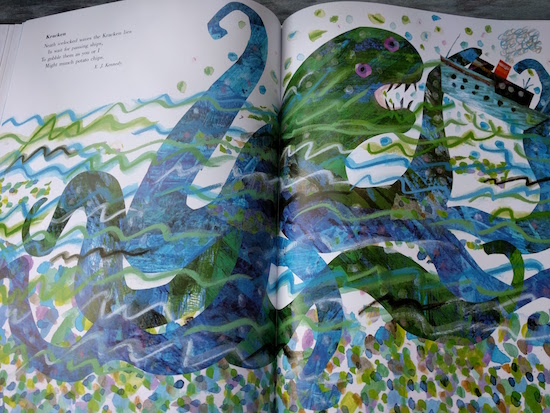

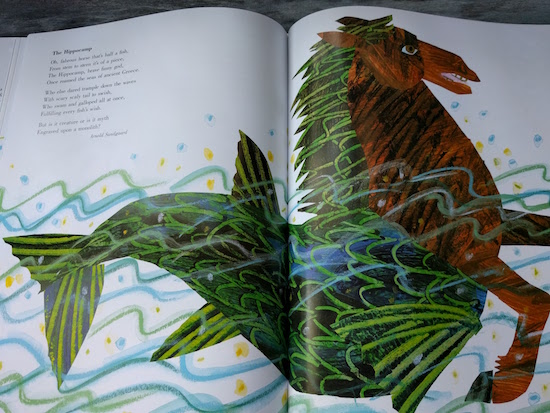

Eric Carle’s Dragons Dragons

How did we live this long without knowing such a book existed as Dragons Dragons & Other Creatures That Never Were? It arrived in the mail this week, a gift from our friend Zsuzsi, whose packages usually contain books we all fall in love with. This one no exception. It’s fantastic, though you probably knew that already. It is possible that I’m last to the party in discovering this book, but on the off-chance I’m not, I want to make sure you know it too. And if you do already, let’s talk about it—isn’t it wonderful?

The anthology pairs poetry from a variety of sources with splendid paintings by Carle of the mythical creatures depicted within the poems. Most interestingly, the creatures come from a variety of sources as well, including from Greek Myth, First Nations stories, Hindu legend, Chinese myth and even the Bible—Levianthan.

You may recall that I was a bit lost when I read Vikki VanSickle’s picture book, If I Had a Gryphon, earlier this year, because so many of the creatures in the story were ones I’d never heard of before. And so Dragons Dragons proved most illuminating, introducing these to me—krackens and chimeras—as well as many others. And if the poetry weren’t explanation enough, there is indeed a glossary in the back disclosing further details, with the most extraordinary caveat…

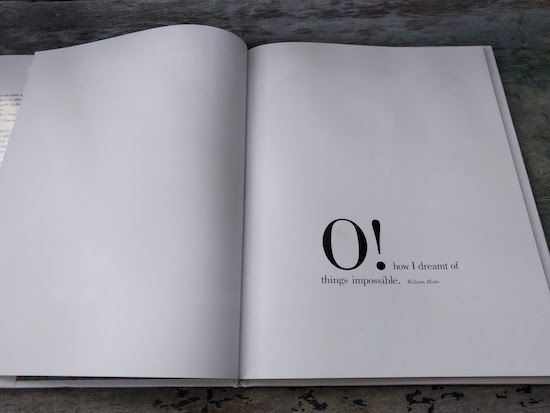

“No glossary can paint a precise picture of the likes of chimeras and dragons and basilisks. These marvellous creations can never be described definitively. Accounts of their appearance vary from source to source and tale to tale. It is appropriate that their images shift slightly in our minds with the storytelling of the moment.”

There’s also a wonderful note by anthologist Laura Whipple on the importance of mythical beasts and what their stories tell us about ourselves, our societies and our histories. “Let us allow our children to revel in the power and mystery of these magical creatures. Let them dream of things impossible.”

June 3, 2016

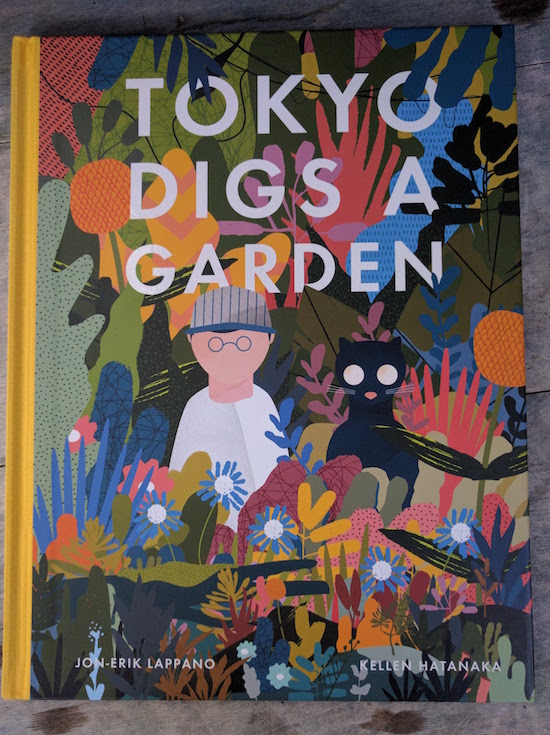

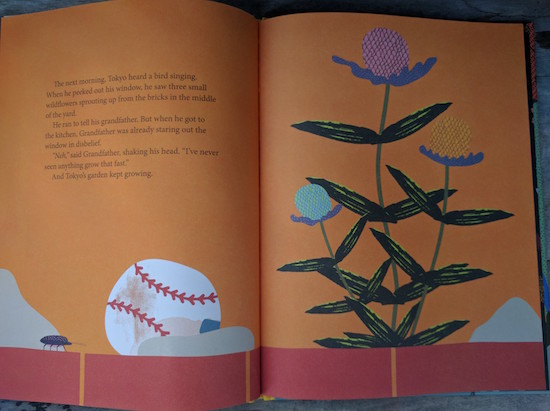

Tokyo Digs a Garden, by Jon-Erik Lappano and Kellen Hatanaka

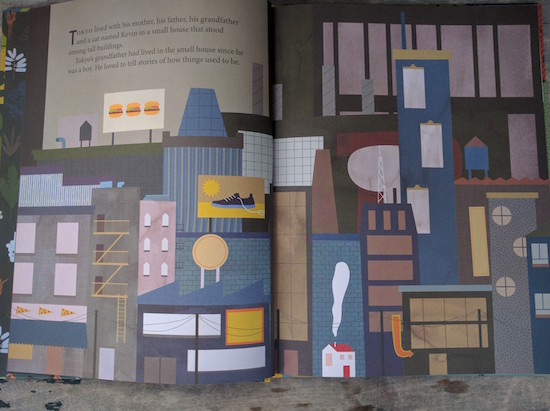

Tokyo Digs a Garden, by Jon-Erik Lappano and Kellen Hatanaka, doesn’t really make sense. It’s about a boy called Tokyo who has a cat called Kevin (who has vivid dreams about ice cream trucks). That it’s about a boy called Tokyo gives one a sense that the story takes place in Japan, and this is suggested by the illustrations, which are by Hatanaka, whose ethic origin is presumably Japanese. But then really, I’m not sure this is a story that takes place anywhere that’s literal. In fact, as suggested by a plot point hinging on a mysterious old lady distributing magic seeds, I’d say that Tokyo Digs a Garden is most certainly a fairy tale. And coupling such an old-fashioned form of story with a contemporary setting (cars, and elevators, and like) and Hatanaka’s new-fashioned illustrations shouldn’t necessarily work, but it totally does, resulting in an effect that is fantastic, weird, deep and textured, and, most wonderfully, a story for story’s sake.

See the small white house with the red roof? That’s Tokyo’s house, and once that house was in the middle of a lush and verdant countryside, but then the city had eaten it all up.

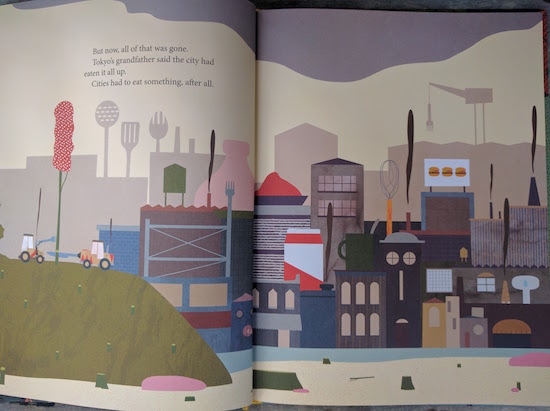

“City’s had to eat something after all,” Tokyo’s grandfather tells him, Hatanaka’s whimsical illustration playing with this idea, the city built of whisks and knives and forks and crockery and spatulas—and it’s a cityscape that reminds me of Maurice Sendak’s in The Night Kitchen.

One day Tokyo and Kevin hear an ice cream truck and rush outside, only to discover no truck and no ice cream, but a very old woman riding a bicycle pulling a cart that’s filled with dirt. The cat’s disappointed, but Tokyo is intrigued to receive three seeds from the woman who tells him to plant them and the seeds will grow into whatever he wishes.

The next day, his grandfather informs him, is a good day for planting, and so Tokyo goes into his backyard (“where nothing is growing. Not even a weed”) and find a small patch of soil when he turns over a brick. He plants the three seeds and we don’t learn what he wishes, but that night he dreams he is a fox running through a forest. Kevin dreams of ice cream.

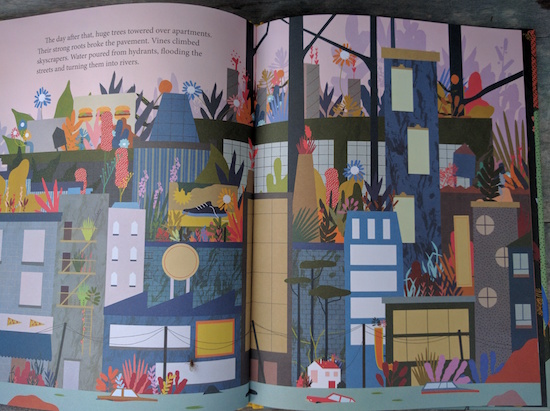

These are no ordinary seeds, of course, but you already knew that. The next morning wildflowers have sprung up between the cracks in the bricks. By the end of the day, there were trees, and by the next morning, “the garden had grown up and over the buildings, across the street, down the road, over the cards, and into the expressway.”

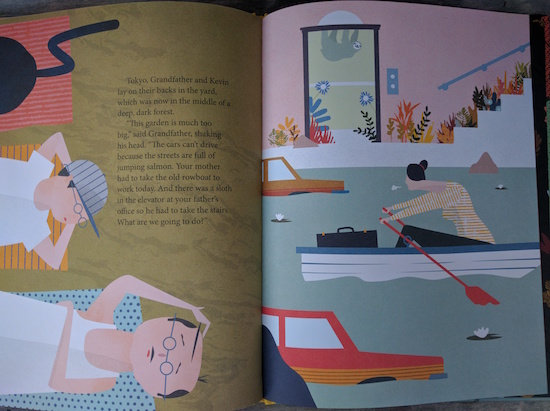

The wilderness grows and grows until vines climb the skyscrapers, roots are breaking the pavement, and the roads are rivers. “The day after that, the city was completely wild. / Deer foraged in office lobbies./ Rabbits burrowed in library carpets./ Bison stampeded through traffic lights./ Bears climbed telephone poles to search for honey where bees had made their hives.”

Underlying this, if one searches, there is some kind of environmental message: about the impact of humans on the environment, about extreme conditions caused by climate change, about the force of wilderness and wildness (which is already apparent in our neighbourhood in early June, as everything has turned so drastically GREEN and the weeds are already exploding) and how we think we are agents of this earth when we are in fact very much just a part of it. A small part. What I like about these ideas is that I’m not sure what the message is exactly—the searching is the point. Tokyo Digs a Garden is not an allegory. There are sloths in the elevator, which I don’t think is supposed to stand for anything but the sloth itself. There is no moral: “I think we’re just going to get used to it,” says Tokyo. “Gardens have to grow somewhere, after all.”

Underlying this, if one searches, there is some kind of environmental message: about the impact of humans on the environment, about extreme conditions caused by climate change, about the force of wilderness and wildness (which is already apparent in our neighbourhood in early June, as everything has turned so drastically GREEN and the weeds are already exploding) and how we think we are agents of this earth when we are in fact very much just a part of it. A small part. What I like about these ideas is that I’m not sure what the message is exactly—the searching is the point. Tokyo Digs a Garden is not an allegory. There are sloths in the elevator, which I don’t think is supposed to stand for anything but the sloth itself. There is no moral: “I think we’re just going to get used to it,” says Tokyo. “Gardens have to grow somewhere, after all.”

May 20, 2016

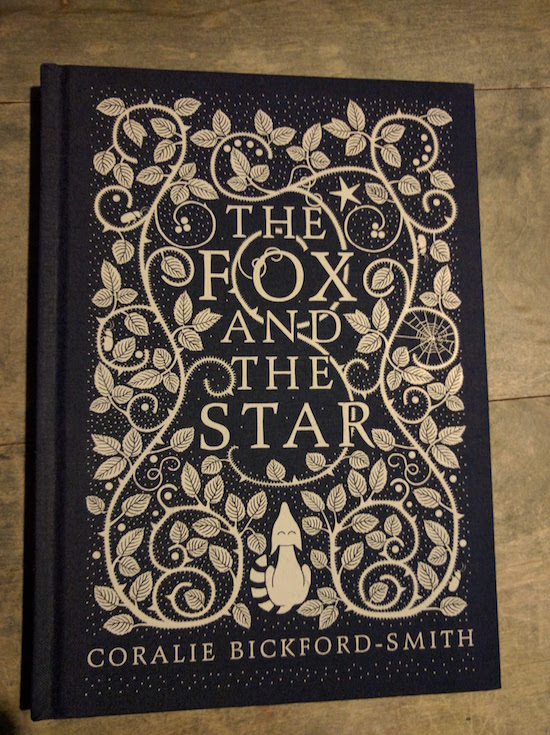

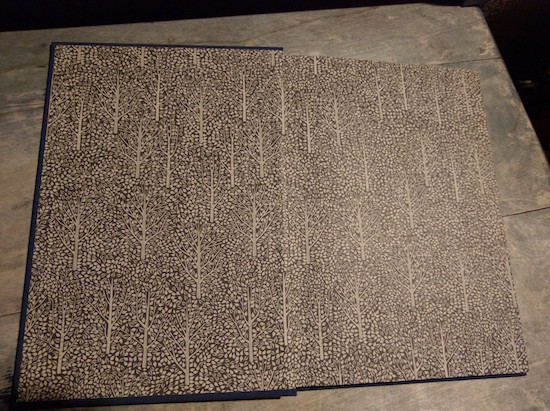

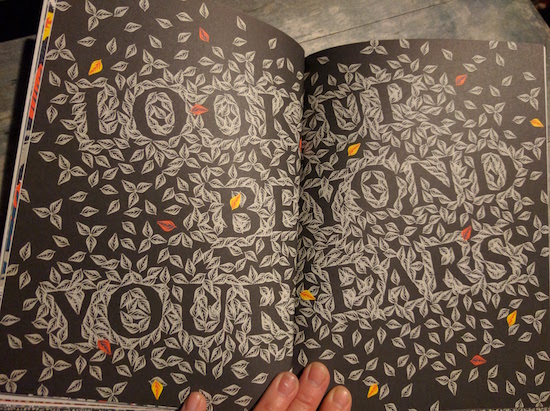

The Fox and the Star, by Coralie Bickford-Smith

So obviously we didn’t end up buying The Dead Bird by Margaret Wise Brown, and got The Fox and the Star, by Coralie Bickford-Smith, which I can’t say is a hardship. And really, that this book is by Coralie Bickford-Smith (world-renowned book designer) tells you everything you need to know about The Fox and the Star: visually, the book is stunning. But does being a book designer necessarily mean that a person can write a book? In the case of Bickford-Smith, it does, in particular because design is so integral to what makes a good picture book work. I’m thinking of an author/illustrator like Virginia Lee-Burton who, like Bickford-Smith, knows the limits of the page and uses those limits and the liminal spaces. There is no single part of the book that doesn’t matter, that doesn’t have attention to it.

Can in point? Endpapers.

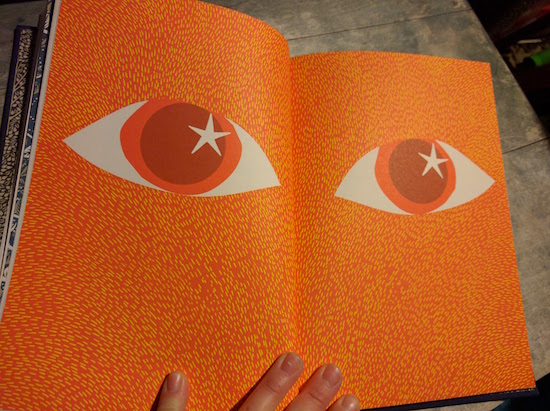

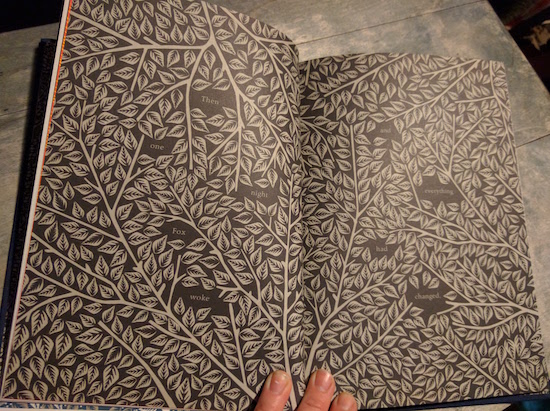

The Fox and the Star is the story of a fox who is small beneath the trees and the sky, but takes comfort in the constancy of a star above him.

The forest is not the the place for constancy though, and one night the fox looks above him and the star isn’t there anymore.

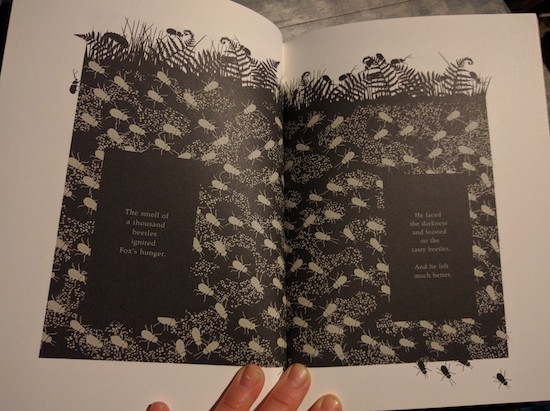

Bickford-Smith shows the life and movement of the forests, above ground, on the ground and underneath it. Her scurrying insects are amazing, as our the rabbits created of white space, and the ferns, and the orange of the leaves as the seasons change, and how she integrates the text into her illustrations. And gradually we begin to understand what has happened to the star.

And as the leaves fall, the fox looks up to find the star again, high up in a sky that’s full of them: “Fox could not believe there were so many stars. His heart was full of happiness.”

This book is exquisite.

May 13, 2016

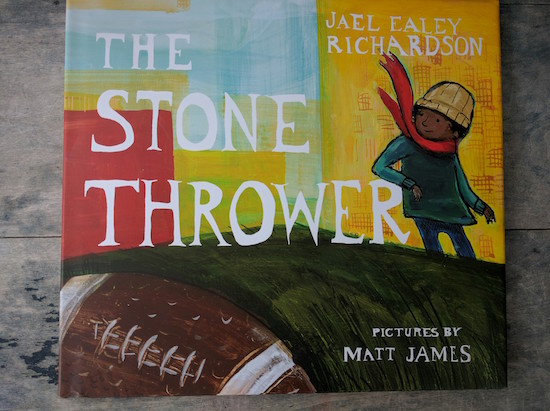

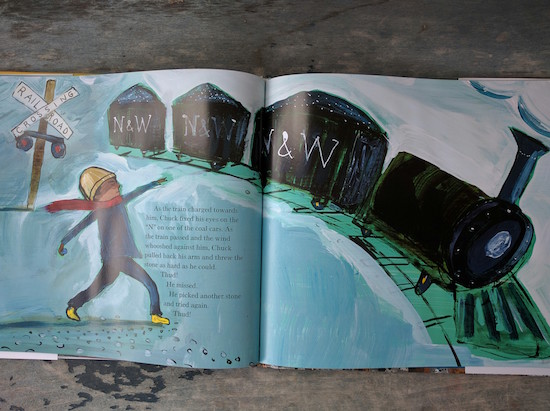

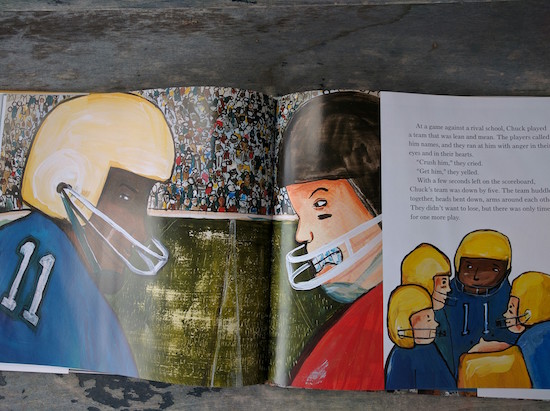

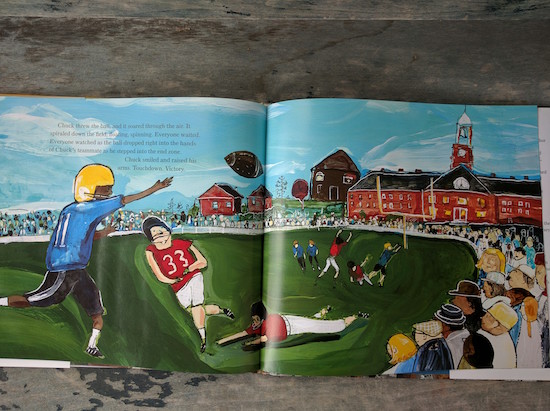

The Stone Thrower, by Jael Ealey Richardson and Matt James

Because this is the week that began with The Festival of Literary Diversity, it only seems fitting to end it with The Stone Thrower, a brand new picture book written by The FOLD’s executive director, Jael Ealey Richardson and illustrated by Matt James (of the award-winning I Know Here). Richardson has told the story before of how an impetus for the festival was her experience promoting her first book, a non-fiction biography of her father, CFL Quarterback Chuck Ealey, and having an indie bookstore owner decline her invitation to visit with the explanation, “This town is very white.”

“There are so many gatekeepers – publicists and sales reps, and bookstore owners, and all these people have to buy into the story in order for you to have any chance,” Richardson explained in her interview with Quill & Quire, and The FOLD emerged as part of an effort to find a way to change that. And now The Stone Thrower is the other creation that Richardson has brought into the world this spring, her father’s story told in picture book form, and it’s every bit as extraordinarily good.

The first time I finished reading this book to my children, we closed the cover a little bit breathless.

“That was really good,” said my oldest daughter, and we made sure to read the book again at night before bedtime so that her dad could know just what we were talking about.

He was also very impressed.

And what do I mean by the fact that this is a book that took our breath away? Because we read a lot of books. We know from good. But rare is the book like this one, with a moral tone as gripping as its story, full of suspense and ultimate triumph, spots of humour, rich and warm illustrations, and prose that feels wonderful in your mouth when you say it.

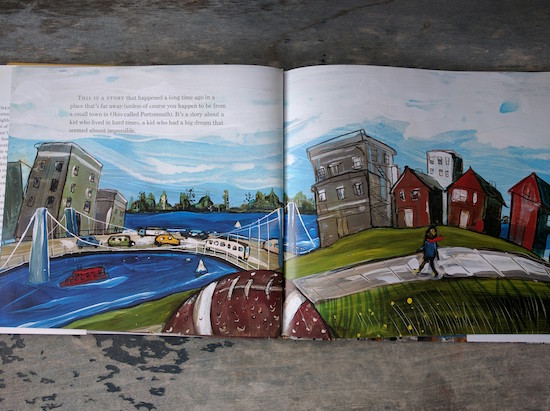

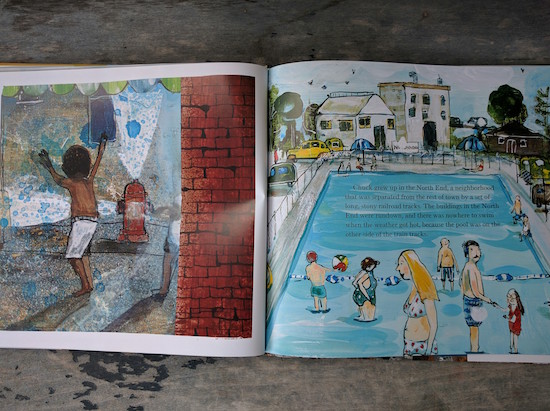

It is the story of a boy called Chuck who grew up in Portsmouth, Ohio, during the 1950s. “It’s a story about a kid who lived in hard times, a kind who had a big dream that seemed almost impossible.” And the odds are against Chuck, a Black kid growing up on what was literally the wrong side of tracks. James’ illustration shows Portsmouth’s white residents cooling off on summer days in a swimming pool, while the kids on the North End, like Chuck, played in the spray from opened-up fire hydrants. Chuck’s mom works hard, but she dropped out of school when she was young and makes very little money. She wants a different kind of life for her son.

“Those coal trains that come through, they don’t stop here,” she said. “I want you to be just like that. Do you remember where you’re going, son?”

While walking down by the tracks, Chuck picks up a stone as the train comes by. Richardson makes her story rich with atmosphere: “The ground began to rumble, and the train tracks shook. The stones along the tracks jumped and bounced like hot kernels of popcorn.” Chuck aims for the N on the N&W on the boxcars (for Norfolk and Western), and throws. And misses. And misses again. But as the last car chugs by, he tries one more time: “BANG! Chuck smiled and raised his hands in victory.”

And this kind of persistence becomes emblematic of Chuck’s experience both in school and in football too, paving the way to his success as quarterback of the school football team. At games, he faces taunts from rival players because of the colour of his skin, but Chuck doesn’t let this break his focus from the object of the game, which is to connect with his teammates and win. And he does. The final words of the story: “Touchdown. Victory.”

The story is made all the more poignant with Richardson’s author’s note at the end of the book, which explains that Chuck Ealey won every game as quarterback of his high school team, and received a scholarship to the University of Toledo, where he won every game there. But after graduating with his college degree (“the best of all his victories”) he finds himself unable to play professional football in America, because the idea of a Black quarterback was still unfathomable to the powers that be.

So he moved to Canada, and played in the CFL, leading the Hamilton Tiger-Cats to the Grey Cup in his very first year. “It’s an unbeatable story that amazes me,” writes Richardson, “even though I’ve heard it all before, because Chuck Ealey happens to be my father.”

In Richardson’s Quill and Quire interview, Groundwood Books Publisher Sheila Barry underlines the need for more contemporary Black figures to inspire young kids: “We have Viola Desmond, but that was a long time ago.” Although obviously, this is a book that will appeal to readers regardless of the colour of their skin.

Together, Richardson and James have hit a target of their own: that of a really great story. And they totally nailed it.

May 6, 2016

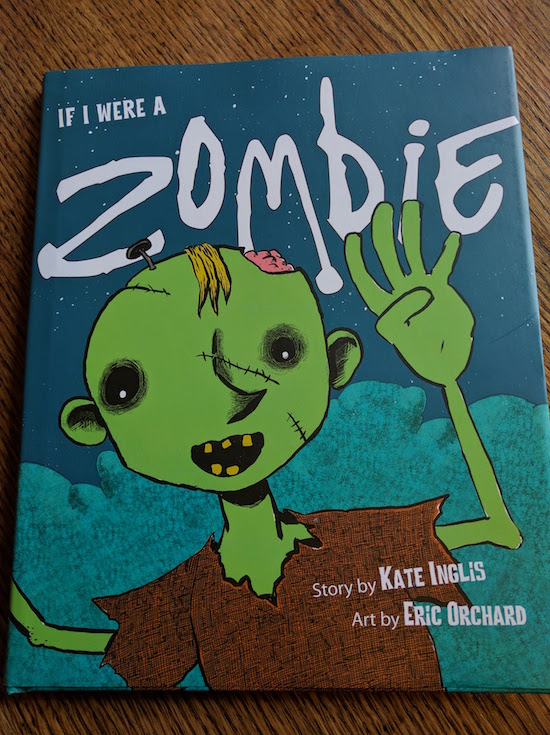

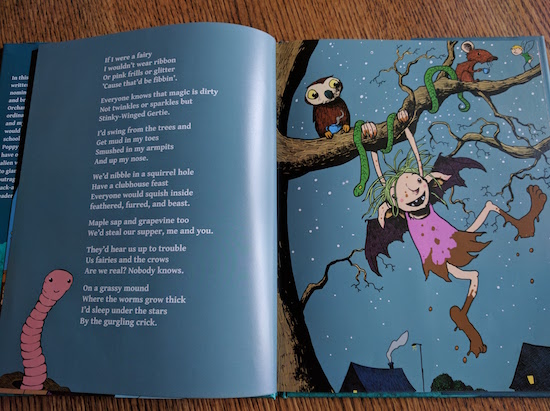

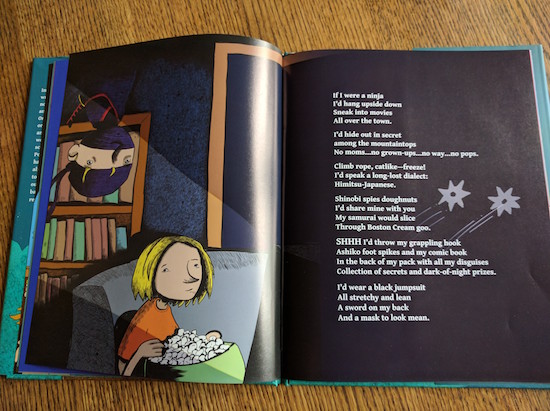

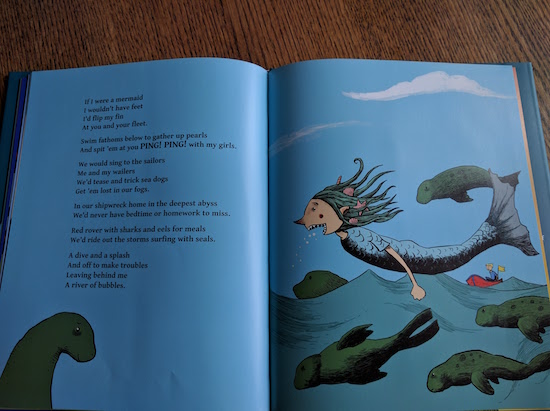

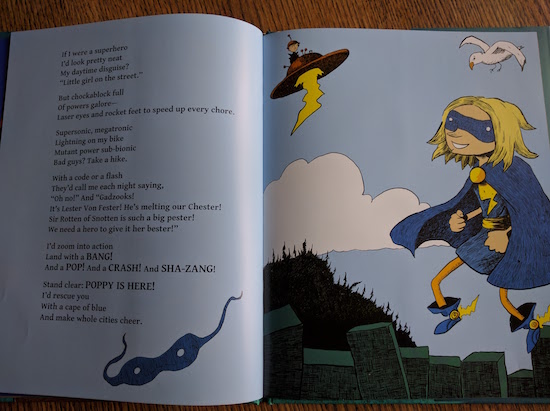

If I Were a Zombie, by Kate Inglis and Eric Orchard

True confession: I don’t really get zombies. Along with “Talk Like a Pirate Day” and Nutella, zombies are a wildly popular phenomena whose appeal I just don’t understand. (I also have no strong feelings about Prince or Shakespeare, which made last week kind of strange.) What I do like is a beautiful picture book though, a kid-friendly one that my children delight in as much as I do, and so to that end, the undead notwithstanding, Kate Inglis’ latest book, If I Were A Zombie, illustrated by Eric Orchard, totally delivers.

The premise is this: the narrator explores the various possibilities for selfhood amidst the kinds of creatures with children tend to be most fascinated: fairies, giants, witches, pirates and vampires. And even actual ninjas! Plus the zombies, of course.

The text is poetry, whose structure reminds me of Sleeping Dragons All Around, by Sheree Fitch (which is by the same publisher). Admittedly, rhyming couplets would have made for an easier read—sometimes the prose is tricky to say, and it’s hard to keep a rhythm—but I am not sure that such bounciness was ever Inglis’s intention. This is also a book that older children will read on their own which makes matters of rhythm irrelevant. And read it, they will. This is a book with zombies and ninjas after all. But there is more to it than that—this is a book about exploring all kinds of being, about possibilities, and adventure, and dreaming up stories for our lives. Teachers and other grown-ups will easily be able to encourage young readers to explore all kinds of “If I were….”s of their own, after trying out the various roles suggested in the book.

My very favourite thing about If I Were a Zombie though is its treatment of gender, assuming boys and girls alike as its readership—and also that all possibilities in the story are open to both of them as well. For a boy to have fairies and mermaids in his story—and I love Orchard’s non-cutesy takes on these. For children to read a book in which the superhero is a girl, which is particularly appealing to my superhero-loving daughter too. I love how gender becomes completely irrelevant, and all possibilities are open to either.

PS: If I Were a Zombie makes a very cool companion to Vikki VanSickle’s If I Had a Gryphon, but concerned with monsters and imagined creatures, as well as the conditional tense.

April 29, 2016

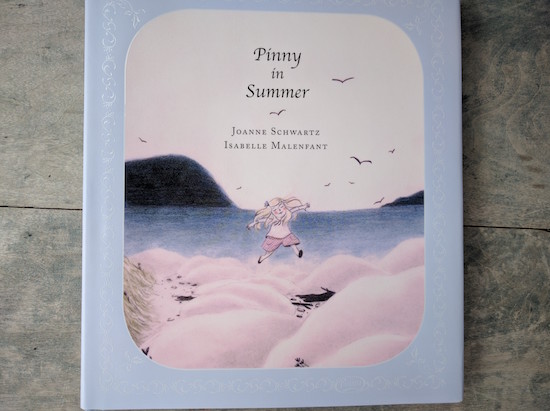

Pinny in Summer, by Joanne Schwartz and Isabelle Malenfant

I owe the most enormous debt to Joanne Schwartz. I met Joanne five and a half years ago when I started attending toddler time at the Lillian H. Smith Library with Harriet, and not only did she introduce me to The Night Kitchen, by Maurice Sendak (which is one of the best things a person can do for anybody), and books by Eve Rice, and Marisabina Russo, and so many others, but she actually taught me how to read a story.

Now I am really, really good at reading stories, but my secret confession is that it’s because I totally stole Joanne’s technique. Which involves talking to children like they’re humans instead of idiots, not employing silly voices, instead a clear voice just not loud enough so that you’ve got to be engaged in order to hear it, and (and this is key) that the voice be thoroughly infused with wonder. So that it’s soothing and animated at once—the most incredible balance.

Joanne’s own books are not so different in approach from the way she reads. She is the author of Our Corner Grocery Store, a fantastic story about a family-run shop , and also of the books City Alphabet and City Numbers, with photographs by Matt Beam, and all of these are books that illuminate the extraordinary in ordinary sights and experiences.

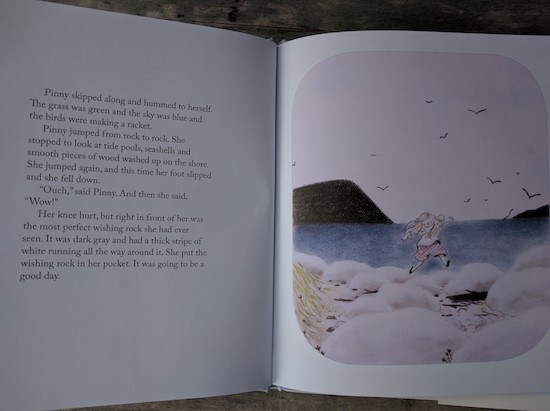

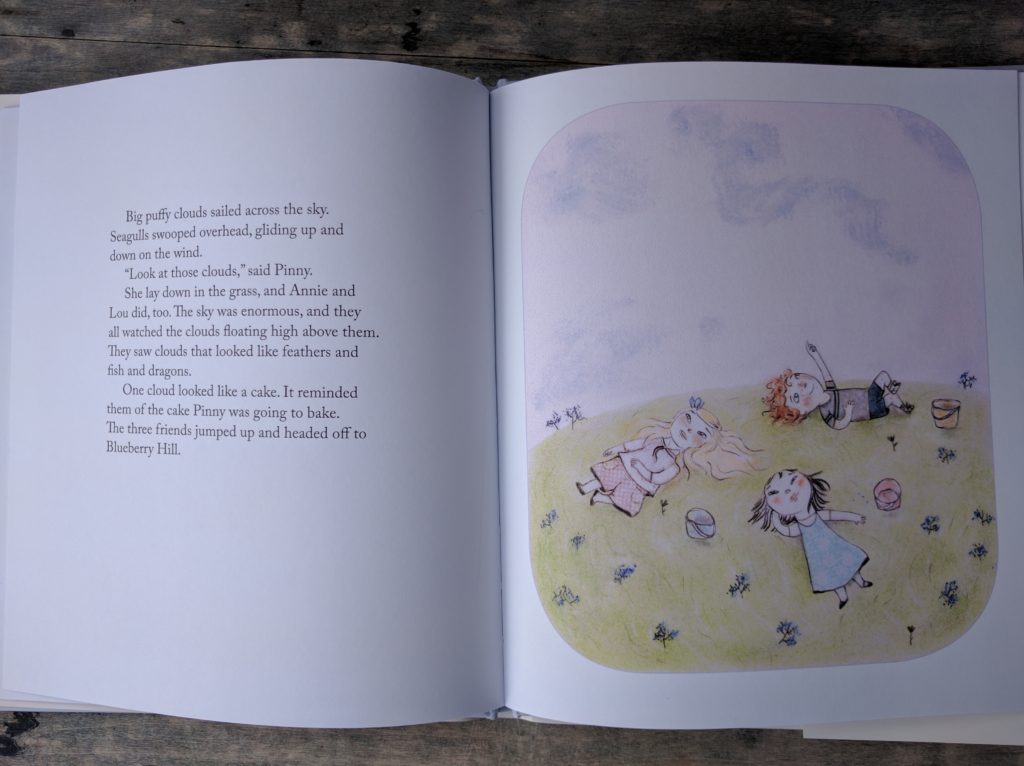

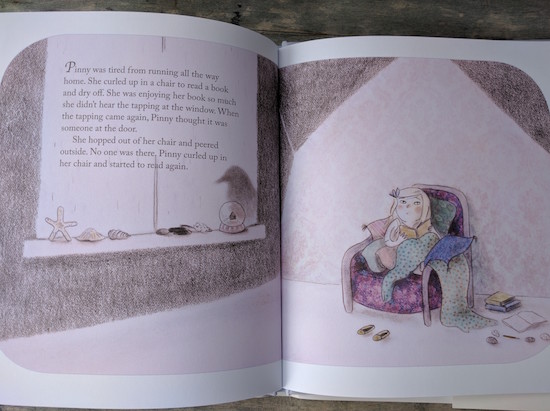

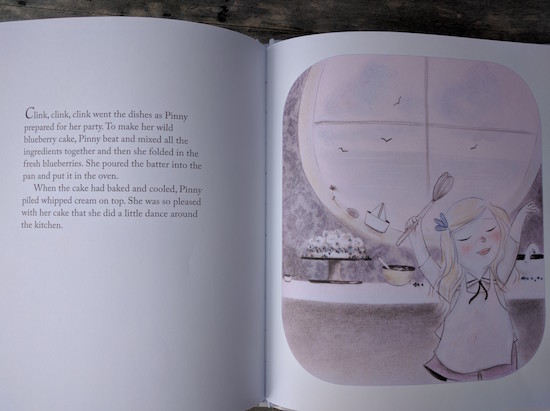

Her new book, Pinny in Summer, gorgeously illustrated by Isabelle Malenfant, fits nicely into that oeuvre, and manages that same balance of soothing and animated, rich with wonder. It’s four little stories in one book, all taking place over the course of a single day—similar in structure to Frog and Toad, or Little Bear. Pinny is a little girl with a whole lot of freedom and so her day contains multitudinous adventures: she finds a wishing stone; she enjoys a session of cloud watching with her friends, Annie and Lou, and then manages to pick a bucket of blueberries before getting caught in a rainstorm. She encounters seagull, then bakes a cake, and it’s around here that it all begins to go a bit wrong—but with a little bit of ingenuity the day is salvaged. And the best thing of all as the sun goes down (and “[t]he sky changed from blue, to a deeper blue, then to dark blue”): there is going to be a tomorrow.

Schwarz’s prose is wonderful—”the sun was shining again, making everything as warm as toast”—and so nice to put your mouth around. Pinny’s adventures are simple but lovely, and are certainly the kind that will inspire a child to dream of similar things. And the story is beautifully bought to life with Malenfant’s illustrations, with shades of blue and violet, simple drawings enlivened by wonderful texture, shadows and darkness at the edges that keep things interesting.

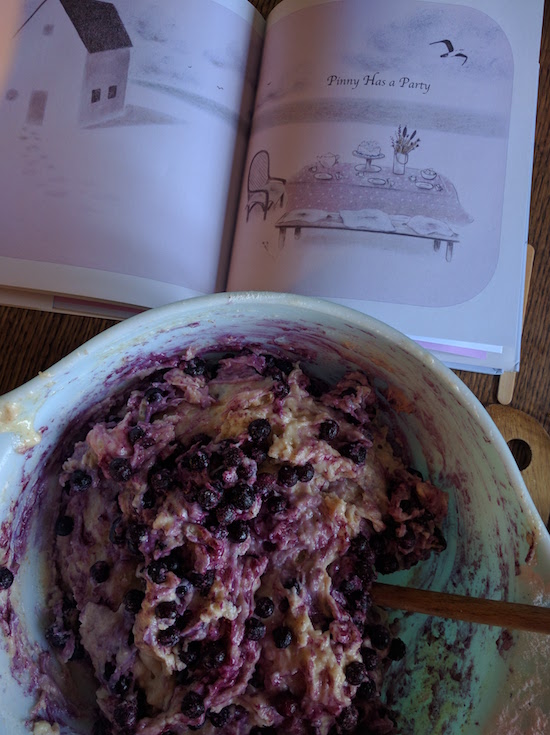

And of course, Pinny in Summer inspired us too. Because I dare you not to read it and want to bake a wild blueberry cake like Pinny does. And so we did, even though our wild blueberries were not picked in buckets on blueberry hill, alas, but came from a bag in the freezer.

All the same though, once we dumped the berries in the mix, the batter turned the same shade of purple as the pictures, which was perfect (and seeing the table set in the image above, you can probably get a good idea of why I love this book so).

The cake was delicious. We froze half for later. And we look forward to spending this summer reading about Pinny again and again.