November 25, 2020

The Seasons of My Life

I have outgrown picture books…again.

Which I feel nervous even writing. If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all, and all that jazz, and I have learned through my interest in kids’ books over the last eleven years that those who create these books can be a bit sensitive about their work, about its relegation to the world of childish things. Wonderful children’s literature appeals to readers of all ages, and readers who restrict themselves to a certain age group (or genre, etc.) are missing out. All of this is true.

But it’s nothing not-nice that I’m trying to say here. Instead, it’s a matter of practicality. That for a long time, picture books were my primary way of engaging with my children and this opened up whole worlds to me, and some of those worlds seemed as real as the one I walk around in every day—but time makes you bolder and children get older, and I’m getting older too?

We still read them sometimes. Iris is only seven and we have so many great books on our shelves that all of us enjoy, books we can recite by heart. There are picture books in our library I’ll never be able to part with, and yet—we’re reading them less and less. I used to blog about picture books weekly, but now I hardly do. Everybody in our family is firmly into chapter books now, books we read on our own and the ones we read together. Picture books don’t have the same integral place in our daily life that they once did.

And none of this is remarkable. Children outgrow a lot of things, and families do too. We used to go on road trips listening to the same CD on repeat, this song with a barking dog in the chorus, because Iris cried in the car otherwise, and we don’t do that anymore. I used to get a big kick out of reading Go Dog Go in ridiculous accents, but these days the dog party is over.

But I feel a little bit disloyal, admitting to giving up on my allegiance to picture books. Or rather, moving on from it—although the new frontier, for me, is middle grade and also graphic novels, and I’m getting the same pleasure from relating to Harriet through some of the novels she’s reading as I once did when we used to examine the illustrations in Allan and Janet Ahlberg’s Peepo together, her gummy baby fingers pointing out the dog in the corner that shouldn’t be there. But I’m also trying to give her space to develop her own relationship with books and reading, one that has nothing to do with me.

And this is what happens, of course, the way things come and go. And how when they go, new things grow up in their place, which I keep reminding myself of in these moments of unprecedented change and upheaval. As businesses shut down in my neighbourhood and city and it’s enough to drive one to despair sometimes, the extent of the loss, all of it so overwhelming and hard. But even harder is trying to hold on to it all.

(And remember: a blog needs space to grow and room to wander!)

It’s okay to grow. It’s okay to change. It’s okay to change again, is what I’m thinking, and for the thing that used to define you so much and mean everything to become a spot of the horizon. And those things we loved will always be a part of who we are, because of the way that we wouldn’t have become ourselves without them.

September 25, 2020

Hope

It’s #CupandSaucerFriday, the “light in the darkness” edition. Jean E. Pendziwol has written a dream of a book with I Found Hope in a Cherry Tree, illustrated by Nathalie Dion, a book whose message underlines my belief (which I stole from Ali Smith’s Autumn) that the stories we tell become what the world is, for better or for worse. And the distinction is up to you, because your actions matter. And hope matters, wherever you find it.

February 28, 2020

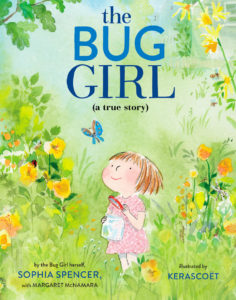

The Bug Girl, by Sophia Spencer

The Bug Girl, by Sophia Spencer, with Margaret McNamara, has a very cool backstory—when a young girl with a passion for insects finds herself bullied by peers, her mother reached out to professional entomologists to offer support for the girl, which went viral. And this is how Sophia Spencer became a debut picture book author at the age of 9, but even knowing none of this, there is a lot to love about The Bug Girl. It’s a book about unabashedly being yourself, about pursuing your own avenues and fascinations, and about defying other people who might hold those fascinations against you. The book is sweet and fun, but also an inspiring call to resist peer pressure, and to understand just how great and wondrous the world is—beyond the limits of one’s own community, and also right down to the smallest creatures on earth.

January 31, 2020

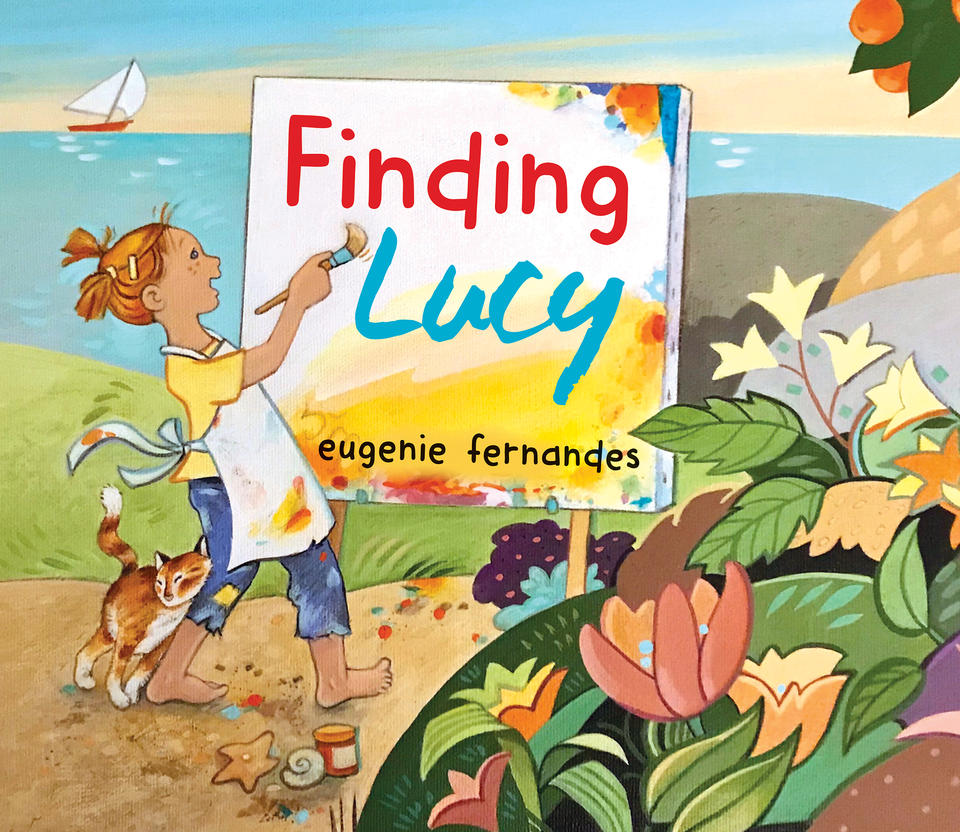

Finding Lucy, by Eugenie Fernandes

I’m not reading picture books as avidly as I once was, which I guess was sort of an inevitable development. Ten years ago, when I had my first baby and was at a loss as to how to relate to her or the circumstances of my mother life, picture books were like a port in the storm, a place where my child’s and my interests actually converged, and they were how I related and connected to my daughter in those early days when her existence was still so alien and strange, and I was overwhelmed and always exhausted.

We’ve hung onto picture books all this time, however, because my children are four years apart, so we’ve stretched out early childhood for an awfully long time in our household, but now my youngest is six and a half, and she’s really into Ivy and Bean. And yes, of course, she reads us picture books now, and my eldest still enjoys them, but they’re not the meat of our literary diet as once upon a time they were. Which is why my #PictureBookFriday posts are getting few and far between. (Blogging tip: let your blog grow and change as you do. Don’t write posts that feel like chores.)

Writing this post doesn’t feel at all like a chore though, because it’s about Eugenie Fernandes’ Finding Lucy, a picture book I’m kind of obsessed with (and I think it’s also Fernades’ first picture book in quite some time). It mingles an old fashioned storybook sensibility (there are talking animals, and the cat is called “the cat”) with a dazzling and delightful abstraction, and the most delicious vocabulary. In fact, this is a book that relishes language just as much as it does colour and art, with words like “discombobulated,” “ferocious” and “atrocious.” “It’s utterly befuddling and baffling and piffling and dribbling and scribbling!” —so say the critics about Lucy’s attempt at a painting.

And yes, everybody has an opinion, as Lucy tries to paint her picture. She wants to paint the colour of laughter, she says, but then a reporter shows up, and then an elephant and a crocodile, and a chicken and a pig (with a pramfull of piglets) and a big city critic who arrives to assess Lucy’s work and have the final say. It’s a story about the necessity of sticking to one’s vision and not having your art be muddled from every elephant or crocodile who happens to wander by. But it’s also a story that’s so much more more than what it’s actually about, a book that’s rich and expansive, celebrating the exuberance of the creative spirit.

December 6, 2019

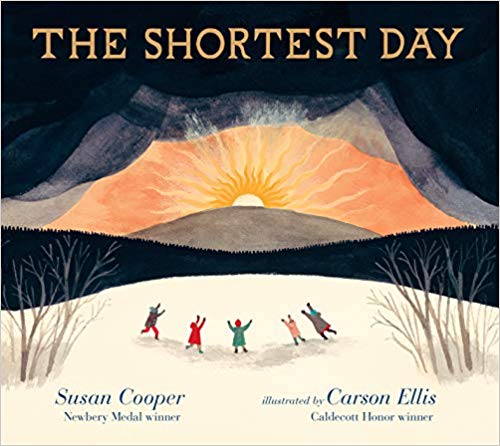

The Shortest Day, by Susan Cooper and Carson Ellis

“So the shortest day came, and the year died…” begins The Shortest Day, an extraordinary picture book by Susan Cooper, with illustrations by Carson Ellis, a celebration of solstice, Yuletide, and rituals that light up the darkness. “And everywhere down the centuries/ of the snow-white world/ Came people singing, dancing,/ To drive the dark away.” In her illustrations, Ellis shows those centuries progressing in Northern European cultures, as people move from the Neolithic era, carrying spears, and then “down the centuries” to the contemporary moment, children revelling in a warm and cozy home decorated with an evergreen tree and boughs, candles and a menorah, traditions that connect us to our ancestors and to the earth. This is one of the loveliest “Christmas” books that I’ve ever come across, a book that celebrates what, to me, are the most sacred parts of the season.

October 25, 2019

The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle, by Anne Renaud and Milan Pavlovic

For some reason, unless they happen to encyclopedic catalogues fun to flip through but with no overarching narrative, non-fiction gets short shrift with the young readers in my house. We’ve got a whole stack of titles about history and animals, dinosaurs, guides to crafting and science experiments, none of them appreciated as well as they should be, and my children read Archie comics to tatters instead.

But The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle, by Anne Renaud and Milan Pavlovic, is the exception to that rule, primarily because it’s a fabulous hybrid of a book—a great story that’s fun to read aloud; a biography based on Frank Epperson who really did invent the Popsicle; a gorgeous book with great design (endpapers to die for!); and it’s got science experiments—on mixing oil and water, how to make fizzy drinks, how to lower the freezing point of water—each one connected to the narrative, which is not only engaging, but also demonstrates the experiments’ real-world implications.

One of my favourite picture book biographies ever is Monica Kulling’s Spic-and-Span!: Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen, and The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle is kind of a companion, a story that blends the scientific and domestic realms, that shows how having children can inspire an inventor’s ideas, a story that makes the familiar extraordinary by taking an every day item (the popsicle!) back to its origins. It also shows how childhood dreams can transform into reality, and how curiosity and an insistence on asking questions can serve a person throughout his life.

October 10, 2019

The Girl Who Rode a Shark, by Ailsa Ross and Amy Blackwell

I’m not yet bored of stories of brave and uncommon women, and this is not even a genre that began with Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls. Virginia Woolf published several biographical essay throughout her career—it was from “Lives of the Obscure,” in The Common Reader, that I learned about the Victoria entomologist Eleanor Ormerod, for example, and without Woolf we wouldn’t even know about Shakespeare’s Sister at all. Truth be told, I actually found Good Night Stories... a bit wanting…but that’s because I’d read Rad Women Worldwide before it, and liked it so much better.

But another similar book, The Girl Who Rode a Shark, by Ailsa Ross (who lives in Alberta!) and Amy Blackwell, has managed to live up to my expectations. My favourite bit is the Canadian content—we’re almost at the Roberta Bondar essay. And Indigenous hero Shannon Koostachin is included in “The Activists” chapter.

The women profiled in the book come from places all over the world, include many women of colour, and also women with disabilities. Even better—while many of the profiles are of historical figures, just as many are contemporary, young women who are out there doing brave and groundbreaking things as we’re reading. A few of these figures are familiar, but more are new to us, and their stories are made vivid and compelling through the book’s beautiful artwork and smart and engaging prose.

October 2, 2019

It Began With a Page, by Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad

It Began With a Page, the new picture book collaboration by Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad—who are already known for their picture book biographies(ish) of Julia Child, Elsa Schiaparelli, Anna Pavlova (illustrated by Morstad, written by Laurel Snyder), and Virginia Woolf (written by Maclear, illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault)—has everything. And to have Kyo Maclear, a leading Asian-Canadian author writing about THE pioneering Asian-American children’s author/illustrator, with illustrations by Julie Morstad who does such justice to her source material. Which is, of course, Gyo Fujikawa’s babies, an adorable array of little people from different ethnic backgrounds, all playing together—Fujikawa has clearly been an inspiration to Morstad since the beginning of her career. But what contemporary readers might not appreciate until reading It Began With a Page—which tells Fujikawa’s life story—is that it wasn’t long ago that picture book illustrations of children with different skin colours all playing together was revolutionary, and before that even not condoned.

Which is a convenient metaphor with which to tell a story of a society in which, just say, people from a certain ethnicity have their land and belongings confiscated and are sent to concentration camps. Although Maclear eschews metaphor altogether here, and sticks with the facts: “In early 1942, terrible things were happening. Bombs and gunfire rocked the world. America was at war with Japan. Kyo was shocked to discover that anyone who looked Japanese or had a Japanese name was no suspected of being the enemy… Gyo’s family was sent to a prison camp far, far away from their home.”

But first: “It began with a page, bright and beckoning.” A five-year-old girl with a pencil in her hand. “The dance and glide of a line. How a new colour could change everything: a bright splash of yellow, a sleep stroke of blue.” The girl fills her pages with drawings, and as she grows older, her talent is natured by a supportive teacher who pays for her art lessons Gyo Fujikawa is one of the few girls, let alone Asian-American girls, who goes to college in 1926. She travels to Japan, her ancestral homeland, to learn about the tradition of Japanese brush painting, and after she returns to America gets a temporary job designing books at Walt Disney’s studio in New York. Which means she is far away from her family when the Japanese internment takes place, but the distance only increases her heartbreak at what is happening in her country.

After the war, Fujikawa continues to work as an artist, and Maclear shows her awareness of the dawning civil rights movement. “Still, there was so much that hadn’t changed. At the library and bookshop, it was the same old stories—mothers in aprons and fathers with pipes and a world of only white children.”

But when Fujikawa submits her manuscript featuring “Babies! Chubby cheeked, squat-legged, bouncy-bottomed babies,” the book is rejected. “No to mixing white babies and black babies. It was not done in early 1960s America, a country with laws that separated people by skin colour.”

Fujikawa, however, does not give up on her vision. And eventually, the book is accepted, and is a huge success, the beginning of an incredible career for this illustrator whose drawings would create “a bigger, better world.”

The story includes a timeline of Gyo Fujikawa’s life, and photographs, and a note from Maclear and Morstad to readers about Fujikawa’s legacy (“Gyo as a TRAILBLAZER…and a RULE BREAKER”) was and how her family supported this book (Fujikawa died in 1998), providing access to stories, photos and archival materials.

June 14, 2019

Ruby’s Birds, by Mya Thompson and Claudia Dávila

Having recently read and loved Ariel Gordon’s celebration of urban forests, not to mention still coming off a recent trip to New York City, Ruby’s Birds, by Mya Thompson and Canadian illustrator Claudia Dávila (we’re big fans of hers) is high up on our list at the moment. It’s the story of Ruby, a young girl with too much energy—so much so that she’s driving her family batty as they’re cooped up in their apartment. And so when a neighbour offers to take Ruby on an adventure to Central Park, she’s totally game, and brings her usual merrymaking self—which is a bit of a problem. Because they’ve gone birding, for which a person must necessarily be quiet, and be patient. Which does not come easy to Ruby at all, but then her patience is rewarded at the sight of a golden-winged warbler.

“We move carefully. We’re serious. We pay attention. We watch for tiny movements in the leaves. We try and try.”

Ruby’s Birds is published by Cornell Lab of Ornithology, whose mission is advancing the understanding and protection of the natural world. The story is fun, the illustrations interesting and dynamic, and the book concludes with information about city birds, the Cornell Lab’s Celebrate Urban Birds project, a list of 14 different species that can be located in the pages of the book and even in the reader’s own city, plus a list of inspiring tips for nature walks. It’s a great book to inspire readers to get outside and get exploring, and perfect for spring.

May 17, 2019

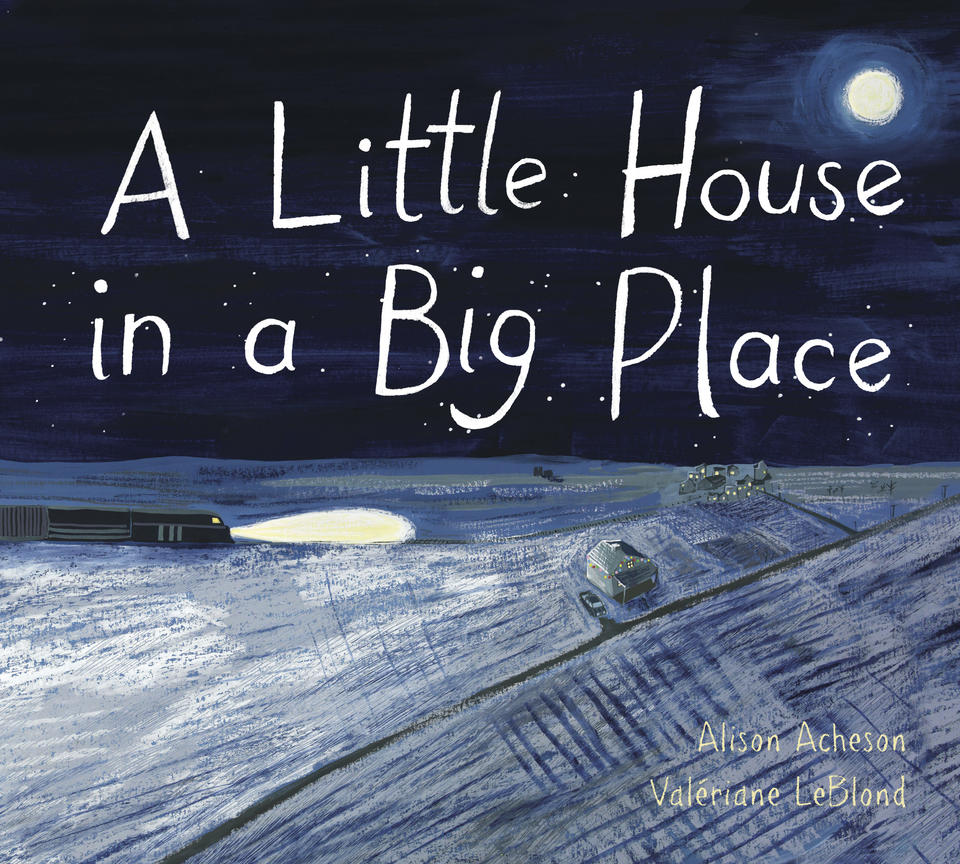

A Little House in a Big Place, by Alison Acheson and Valériane Leblond

We are in love with A Little House in a Big Place, by Alison Acheson and Valériane Leblond, a picture that manages to combine an old-fashioned sensibility with a storyline that’s utterly surprising. It’s the story of a young girl who lives in a house on the edge of a small prairie town, and every day she stands at her window and wave that the train engineer who goes past. “…[A]nd she wondered. About where he came from and where he went. And if she might go away too, someday.”

And we hear the story too from the point of view of the engineer, who waves to the girl everyday. The prairie landscape informing the narrative’s perspective: “His train came over the horizon every morning. One moment there was only sky, and the next moment there would be a dot/ that got bigger/ and bigger/ and bigger [the text getting larger with each line] and the dot would become the train.” And the train rushes away until it becomes a dot again. “But his wave and her wave together made a home in [the girl’s] heart.”

The girl wonders about the engineer, as he no doubt wonders about the girl in the window of the small house on the prairie, and they’re connected to each other, though neither knows the other at all. The girl has no idea that one day will be the train engineer’s last day on the job—but then he throws something from his window that she runs through the fields to find. And he will never know it, but the girl will carry it with her through her life.

I have a theory that this book is a secret ode to Joni Mitchell, because the end of the story finds that small girl who grew up in a prairie town living in a place far eastward, strumming her guitar in a coffee shop. But there is a universality about the story too, about the anonymous people who touch our lives, and about the places where we come from, which set us on the road towards where we’re meant to be.