October 16, 2017

My Conversations With Canadians, by Lee Maracle

Have you ever listened to Lee Maracle speak? I hadn’t, except for a spot on the radio last year where she totally stole the show. Which meant that I kind of knew what I’d be getting into when I went to her presentation at The Word on the Street last month, and she delivered completely. Terrifyingly smart, warm, informed, funny, biting, and not here for any of your shit, was the impression I got from Lee Maracle. I bought her book immediately after the session, the new essay collection My Conversations With Canadians, the latest in BookThug’s Essais non-fiction series. It’s a book born of Maracle’s experiences over the years addressing audience questions at book events, the book’s most central one being from the old man who gets up and asks her, “What are you going to do with us white guys—drive us into the sea?” Never mind Maracle’s formidable response to him, which you’re going to have to read the book to figure out, but I’m still hung up on the man himself, what he stands for. How do you get to be the person with nerve enough to stand up and demand anything of Lee Maracle, is what I’m wondering about, not least because, well, it means that you get to talk instead of Lee Maracle. I don’t have a problem with self-esteem, but I’ve never thought highly enough of myself for that.

Have you ever listened to Lee Maracle speak? I hadn’t, except for a spot on the radio last year where she totally stole the show. Which meant that I kind of knew what I’d be getting into when I went to her presentation at The Word on the Street last month, and she delivered completely. Terrifyingly smart, warm, informed, funny, biting, and not here for any of your shit, was the impression I got from Lee Maracle. I bought her book immediately after the session, the new essay collection My Conversations With Canadians, the latest in BookThug’s Essais non-fiction series. It’s a book born of Maracle’s experiences over the years addressing audience questions at book events, the book’s most central one being from the old man who gets up and asks her, “What are you going to do with us white guys—drive us into the sea?” Never mind Maracle’s formidable response to him, which you’re going to have to read the book to figure out, but I’m still hung up on the man himself, what he stands for. How do you get to be the person with nerve enough to stand up and demand anything of Lee Maracle, is what I’m wondering about, not least because, well, it means that you get to talk instead of Lee Maracle. I don’t have a problem with self-esteem, but I’ve never thought highly enough of myself for that.

Of course, the question I am asking is rhetorical; how do you get to be that guy? And the answer is white supremacy and patriarchy. Which doesn’t absolve me, of course. Which doesn’t place me outside of that audience of Canadians that Maracle is addressing in these essays. Some of which made me uncomfortable, actually—my experience of the world has left me with no understanding of the power of song, for example, which Maracle writes about in her first essay: “we can sing you up to wellness or sing you down to illness, even death. It is the power of our songs. We could even raise our poles with song.” I delineate this to show that even though much of Maracle writes about does not make me uncomfortable—centralizing indigenous experience, issues of cultural appropriation and stealing stories; the necessity of elevating oratory; fiction as a powerful truth—that I understand the experience of someone who might approach the book and its ideas with some hesitancy. Someone who doesn’t know quite yet that the point is to be unsettled after all.

“It is not enough to acknowledge something—you must commit to its continued growth and transformation,” Maracle writes in her essay, “What Do I Call You?” Which is to say that learning and growing is the very point, that being progressive is a process and one you’re never finished with if you’re doing it properly. Which is why welcoming this experience of being unsettled is the very point, along with sitting the fuck down and listening.

I loved this book. I love the way that Maracle peppers her work with allusions to so many incredible Indigenous writers in Canada who are changing the world, sentence by sentence, how My Conversations With Canadians is also the most terrific bibliography. I love how she writes about Indigenous identity, and how Canadian identity is never questioned, or at least not in a non-superficial way. “I am not quite sure how the identity of Indigenous people became fallible and questionable to Canadians, while their own identity is not, but I can say this much: I do not recall ever having doubts about my identity, The point they are making is that my identity is violable—it can be violated.” (Which reminds me of Camille T. Dungy’s comments about her identity as a Black woman: ‘that you see me as a “regular” person suggests that in order to see me as regular some parts of my identity must be nullified. Namely, the parts that aren’t like you.’)

Maracle writes about intersectionality, about feminism, she dismantles the myth of Canadian niceness, and the myth of objectivity too, and then writes about the true myths that are “the path to truth and knowledge”—something science, she writes, is only just beginning to understand. About giving up “the knower’s chair,” which assumes that we as Canadians as the teachers, and Indigenous people our students (i.e. sit down, bellowing old man!). Gender binary and making a link between the idea of binary and that which binds us, an etymological link that had never occurred to me before. A whole chapter is devoted to cultural appropriation, and knowledge and stories as an inheritance which has been stolen from Indigenous children. (Here I’ll repeat something I’ve written before, that until I read Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian, I really thought that the theft we talk about in terms of what was taking from Indigenous people was mostly metaphorical. I had no idea…)

She writes, “Rather than looking at where we are in a hierarchical order of things, we should look at our responsibility toward the lives we are dependent upon. In any relationship, we have responsibilities, obligations, and disciplined interaction. We cannot simple do “whatever we want” in the name of freedom.” I also loved this in a following paragraph, “All engagement is a moment of sharing, every morsel of food a moment of sharing from earth to us and back.” In that same essay, “Humility is crucial to recognizing and examining our failures, our mistakes, our contribution to broken relations…” And then she goes on with this brilliance, “Do not mistake my kindness for acceptance of the absence of the right of access to my land or my love for it. Further, do not mistake my kindness for a relinquishment of who I am and who I will always want to be.”

“Settlers ought to look at their history, then look in the mirror. After annihilating our populations, and much of the animal life on this continent and in the oceans, and after spoiling the air, and the waters, who would want to be you?”

Are you unsettled yet?

As I read this book, I kept thinking of the bellowing man asking questions, and that guy had become a stand-in for the kind of Canadian journalist who has made an industry out of writing about Indigenous issues, not so subtly underlining his racism with every click on his keyboard. About how all this focus on colonialism and intergenerational trauma, and de-centreing whiteness, and giving credence to Indigenous forms of knowledge has, well, threatened to destabilize our white supremacist patriarchal society, and for obvious reasons this really bothers this guy. Because of how he refuses not to see himself as central, as neutral, as non-complicit in any of the systems that perpetuate the tragedy of Indigenous people and their communities.

What would happen if he read this book, I wondered. Like actually read, instead of making inflammatory notes in the margins and planning his rebuttals. What if the bellowing old man actual shut up, sat down and listened?

In the words of poet Muriel Rukeyser: perhaps the world would split open.

October 10, 2017

Dazzle Patterns, by Alison Watt

When I’m reading historical fiction, it always takes me a bit of time to get settled in the story, to find my bearings in terms of place and time. It’s like travelling to any land that’s a bit foreign, I suppose, where the customs and language aren’t quite what you’re familiar with. And so I knew to be patient when I started reading Dazzle Patterns, the debut novel by Alison Watt, whose previous works include poetry and award-winning non-fiction. Which wasn’t hard because the premise was compelling: a young woman is working in the local glassworks in Halifax in 1917 as a flaw-checker, dreaming of passage to Europe where her fiancé has been fighting. Parts of the story is also from his point of view, Leo, traumatized after surviving the Battle of Passchendaele, though he doesn’t write that home in his letters. And the other protagonist is Fred Baker, an artisan who works with Clare at the glassworks. He’s the one who delivers to her the hospital on that December day when two ships collide in Halifax Harbour, leading to the explosion that levels huge swathes of the city, leaving so many Haligonians dead or injured. Fred spends the next few days working without ceasing in the overcrowded makeshift morgue, but this doesn’t keep him from falling under suspicion by his colleagues and official authorities—though he’s long been a Canadian citizen, Fred was born in Germany, and there are many people in Halifax who aren’t convinced that the explosion was an accident.

When I’m reading historical fiction, it always takes me a bit of time to get settled in the story, to find my bearings in terms of place and time. It’s like travelling to any land that’s a bit foreign, I suppose, where the customs and language aren’t quite what you’re familiar with. And so I knew to be patient when I started reading Dazzle Patterns, the debut novel by Alison Watt, whose previous works include poetry and award-winning non-fiction. Which wasn’t hard because the premise was compelling: a young woman is working in the local glassworks in Halifax in 1917 as a flaw-checker, dreaming of passage to Europe where her fiancé has been fighting. Parts of the story is also from his point of view, Leo, traumatized after surviving the Battle of Passchendaele, though he doesn’t write that home in his letters. And the other protagonist is Fred Baker, an artisan who works with Clare at the glassworks. He’s the one who delivers to her the hospital on that December day when two ships collide in Halifax Harbour, leading to the explosion that levels huge swathes of the city, leaving so many Haligonians dead or injured. Fred spends the next few days working without ceasing in the overcrowded makeshift morgue, but this doesn’t keep him from falling under suspicion by his colleagues and official authorities—though he’s long been a Canadian citizen, Fred was born in Germany, and there are many people in Halifax who aren’t convinced that the explosion was an accident.

Clare begins to recover from her injuries as Halifax itself slowly rebuilds after the tragedy, and she’s pulled between her parents’ wishes to shelter her and her yearning for independence. When Leo is reported missing, Clare realizes that she’s lost her getaway plan, as well as her fiancé, and contemplates the limits of the future before her. To stay busy as her recovery continues, she begins taking painting lessons at the School of Art, where Fred is also a student. And the connection before them does not occur in cliched ways one might expect, because this is too interesting a story for that, besides there are complications—Clare still loves Leo, and her landlady’s daughter has fallen in love with Fred.

These central strands to the story become woven in a wonderful fashion. The novel’s title comes from the patterns painted onto ships to break up their silhouettes and make the vessels more protected from German U-Boats, which is just one very practical role that artists played in supporting the war effort. Watt portrays other roles as well, artists documenting the war by painting battlefields and the ships in Halifax Harbour, real-life Canadian artists appearing as characters in the book alongside Fred and Clare. The intricacy of glasswork in particular is an important element of the story, glass’s amazing technological capabilities but also its fragility. This is a novel about art, and vision, about seeing, and looking carefully at things—and about what happens when other people fail to do so. The Halifax Explosion and World War One are the book’s backdrop, but not its reason for being—and these historical events aren’t manipulated either to become metaphors to serve the author’s purposes. War and destruction are brutal and violent with long-term ramifications that take years to come to the surface. There is nothing heroic about any of it, except for the people who show up to help others.

And so there would eventually come a point when Dazzle Patterns won me over entirely, as you’ve probably noticed, when its people and the streets they walk on became as vivid as the room I’m sitting in now. I loved this book, the art of its tapestry, all of it leading toward an ending that was absolutely perfect.

September 25, 2017

Once More With Feeling, by Méira Cook

“This novel was not what I was expecting,” I wrote in my review of Méira Cook’s debut novel, The House on Sugarbush Road, in 2013, and it makes me laugh to see that now, because it’s exactly what I was going to say about her latest novel, Once More With Feeling. Possibly the only thing a reader can do with a Méira Cook novel is have no expectations at all. Because if you do, she’ll only grab you by them, and then swing you around and around her shoulder like a cowboy with a lasso. Or at least this was my experience of Once More With Feeling, which I’d been led to believe via the cover copy would be sweet and heartwarming, doddering professor Max Binder delivering an ill-advised gift to his wife on her birthday, the wife he’s still besotted with. I’d been setting myself up for a sweet comedy, a little bit homey and twee. But then the car drove off the road… Metaphorically and otherwise, and here we were barrelling down the off-roads, narratively speaking.

“This novel was not what I was expecting,” I wrote in my review of Méira Cook’s debut novel, The House on Sugarbush Road, in 2013, and it makes me laugh to see that now, because it’s exactly what I was going to say about her latest novel, Once More With Feeling. Possibly the only thing a reader can do with a Méira Cook novel is have no expectations at all. Because if you do, she’ll only grab you by them, and then swing you around and around her shoulder like a cowboy with a lasso. Or at least this was my experience of Once More With Feeling, which I’d been led to believe via the cover copy would be sweet and heartwarming, doddering professor Max Binder delivering an ill-advised gift to his wife on her birthday, the wife he’s still besotted with. I’d been setting myself up for a sweet comedy, a little bit homey and twee. But then the car drove off the road… Metaphorically and otherwise, and here we were barrelling down the off-roads, narratively speaking.

Once More With Feeling is not an easy book. (I think I said this about The House on Sugarbush Road as well.) It won’t be to everyone’s taste and there are things about it that are troubling, and I would have appreciated the end coming just a bit sooner than it did. I started reading this book on a plane, and to be completely honest there were a couple of points early on where I might have put the book down, had I not been thousands of feet in the air without another book to read. Not a singing endorsement, I know, but bear with me. I kept going, and it was not long after that it became clear to be that there was actually no better book for a four hour flight, or no situation better than a flight to enjoy a book like this. To give it the sustained attention it requires, and to have my reading time so richly filled with so many voices and stories. It’s hard to appreciate a feast in tiny bites, is what I mean, and so it was nice to just keep my seatbelt on and read voraciously.

Once More With Feeling is a novel about a city, Winnipeg in four seasons, although Winnipeg isn’t named. It’s specified though, and it reminded me of my favourite Winnipeg novel, Carol Shields’ The Republic of Love, in how the city is evoked, the sweep of its year. The two books are complementary, though Once More With Feeling is darker, with an edge. And every chapter is from a different perspective, connections between some of the characters tangential, and we get to see some of them from their internal monologues and also from far away. There is startling ambition as to the range of characters how share the story’s helm, a relay passed from one to another. Literature Professor Max Binder, then his wife’s editor at the local newspaper (whose contents we glimpse via letters from outraged readers). The newspaper’s spinster bookkeeper (who has a secret life of her own, surely) volunteers at a local mission that serves food to the homeless, and so the next chapter is from the perspective of another volunteer, whose mother is the Binder’s cleaner and whose sister is just one of many women who’ve gone missing on the city’s streets. And onward, through Max Binder’s children, and their schoolmates.

My favourite chapter was “Inspirational Living Centre,” from the perspective of a wayward high school student whose class gets paired up with Holocaust survivors. And while the bubbly popular girls in the class embrace this experience (“On the way back from the Inspirational Living Centre some of the girls said theirs were “cute” and Courtney Segal even said hers was “adorable.”) But the narrator is matched with a curmudgeonly asshole who refuses to be inspirational, and even ticks off Courtney Segal on the bus ride home—”Why can’t you keep your Holocaust survivor from bothering ours?” she demands.

Teenagers at the mall, a camp director in September, a chorus of Jewish mothers reflecting on Bar and Bat Mitzvahs past in a chapter that reminded me of Grace Paley (in which time made a monkey of us all). A chapter from the perspective of Lazer Binder’s English teacher’s ex-hushand, the Binders’ next door neighbour, two elderly sisters, and then back to Maggie after a year of grief and rage and the arrival of the missing piece of the puzzle of what ultimately happened to Max. And what is the plot? Which is the same question as what propels the story? Well, the sweep of days and months and change of the seasons, of course, the furious momentum of life itself, in a city in particular where nothing sits still for a moment.

Although with a Méira Cook novel (and this is her third) the language is as important as the plot is, and the vocabulary of this one is rich and dextrous. Cook is an extraordinary writer, an award-winning poet, as adept at plotting words as story—her sentences are truly magnificent.

September 21, 2017

The Mother, by Yvvette Edwards

Last week I read The Mother, by Yvvette Edwards, a really beautiful and harrowing story of a mother attending the trial of the boy whose been accused of murdering her teenage son. Written in the first person in a voice that is raw and sometimes faltering, it’s not an easy read emotionally, but the novel is also fast paced and gripping. It evokes interesting question about motherhood, race, class and the ways in which we all assume our families, our children, can be inoculated against the social problems outside our warm and and cozy homes. The ways in which we assume too that we can exist apart from the world and its violence, and that there are issues we can say with certainty, “That is not my problem.”

It’s a deeply thoughtful and warmly provocative novel, Edwards’ second after A Cupboard Full of Clothes, which was long listed for the Man Booker Prize and shortlisted for the Commonwealth Prize. I learned of this title after reading Donna Bailey Nurse’s interview with Edwards, which you can read here—and I am so glad I did.

From Donna Bailey Nurse: “I admire Edwards’s authentic portrayal of Caribbean men and women. She is particularly adept at capturing the lithe movements of a certain kind of West Indian male. I was not surprised to learn that Toni Morrison is her “star” author or that she counts Beloved among her most cherished novels. As in Beloved, Edwards works with the opposing forces of murder and motherhood. And like Morrison, the psychological action of her fiction unfolds largely within the realm of black people. In The Mother Edwards describes the harsh circumstances and complex dynamics of an embattled community. At the same time she conveys the sense of a black British family rooted firmly in love.”

September 19, 2017

We All Love the Beautiful Girls, by Joanne Proulx

A thing I think is funny is a description in Joanne Proulx’s biography accompanying her recently released second novel, We All Love the Beautiful Girls. Among much acclaim for her previous novel is the detail that it won “Canada’s Sunburst Award for Fantastic Fiction,” which would be a cool award to be win, I imagine. To be officially fantastic. Although the tag for the Sunburst Award is “for excellence in the Canadian literature of the fantastic.” Which is to say genre, sci-fi and fantasy. Which is to say that Proulx, whose previous book was the YA title Anthem of a Reluctant Prophet, as an author requires tricks to be packaged, wrapped up tidily in a neat little box for her mainstream novel about the perils of modern family life.

A thing I think is funny is a description in Joanne Proulx’s biography accompanying her recently released second novel, We All Love the Beautiful Girls. Among much acclaim for her previous novel is the detail that it won “Canada’s Sunburst Award for Fantastic Fiction,” which would be a cool award to be win, I imagine. To be officially fantastic. Although the tag for the Sunburst Award is “for excellence in the Canadian literature of the fantastic.” Which is to say genre, sci-fi and fantasy. Which is to say that Proulx, whose previous book was the YA title Anthem of a Reluctant Prophet, as an author requires tricks to be packaged, wrapped up tidily in a neat little box for her mainstream novel about the perils of modern family life.

And this is makes We All Love the Beautiful Girls so interesting, I think. Fantastic, even, in the non-supernatural sense of the word. It makes the novel not wrapped up or tidy or boxy in the slightest, instead furious with momentum, bursting open, exploding at seams.

I read the second half of this novel in a few hours one Saturday night, because it was a story that just kept going and going. Although I wasn’t sure at the very beginning, when all the action gets out of the way in a chapter or two: Michael and Mia discover they’ve been bilked out of their life-savings by a business partner/friend, and then their son, Finn, passes out in the snow at a party, nearly dying, with injuries he’ll carry with him for the rest of his life. All of this within the first 50 pages of a book over 300 pages long—what else can happen? Oh, only everything, and it’s how Proulx frames this narrative that is so fascinating, not on the drama itself but on unintended consequences, the shocking, tragic and terrifying ways that one thing can lead to another.

This is a novel with sharp edges and tight corners, and it’s a novel not afraid to make its reader uncomfortable. Told from Michael and Mia’s points of view in third-person and Finn’s in first person, the narrative is fragmented, patchwork, and then all the pieces become drawn together in the most disturbing fashion. And then it dawns on the reader as it dawns on the characters, that all these things are connected—objectification of and/or violence against women in particular, and how each and every character is implicated, and we see that that two characters peripheral to the story—Jess, a former babysitter now college student who sneaks in Finn’s window to sleep with him; Frankie, Finn’s contemporary whose feelings for him aren’t returned—and Mia herself are not so far apart after all in their experiences of womanhood and what is required for survival.

Some of the very worst things are what turn out to be universal.

September 12, 2017

What is Going to Happen Next, by Karen Hofmann

A group of siblings running wild in rural British Columbia, under the dubious care of their hippie dad while their mother has been hospitalized for psychiatric problems. We first glimpse them through the point-of-view of twelve-year-old Cleo who sees herself as the family lynchpin, caring for her younger brothers along with her older sister, Mandalay. Just barely holding it together, and then their father dies. The police are at the door. Cleo is trying to pass herself off a a responsible agent, so earnestly that the reader can almost forget that she is only a child. But she is indeed only a child, and her baby brother will be adopted, Cleo and her brothers placed in foster care, Mandalay in a group home. Each of the siblings set in very different orbits…and the novel actually begins twenty years on from all that.

A group of siblings running wild in rural British Columbia, under the dubious care of their hippie dad while their mother has been hospitalized for psychiatric problems. We first glimpse them through the point-of-view of twelve-year-old Cleo who sees herself as the family lynchpin, caring for her younger brothers along with her older sister, Mandalay. Just barely holding it together, and then their father dies. The police are at the door. Cleo is trying to pass herself off a a responsible agent, so earnestly that the reader can almost forget that she is only a child. But she is indeed only a child, and her baby brother will be adopted, Cleo and her brothers placed in foster care, Mandalay in a group home. Each of the siblings set in very different orbits…and the novel actually begins twenty years on from all that.

Cleo is a middle-class mother of two small children, overwhelmed by the excruciating demands of early motherhood and hungry for intellectual stimulation. Hofmann so exactly captures the claustrophobic impossibility of life with small children, and all the details that can trip one up—navigating strollers through rough terrain, the preparation and work required for a trip on the bus. The loneliness too, and this is only added to as the unnavigability of the world with small children keeps Cleo close to home. That she has no example in her own past of functional family life leaves Cleo even more stranded than the average mother of young children. Her husband is not without sympathy, but he’s frustrated, and not receptive to what his wife is going through.

Meanwhile, Cleo’s sister Mandalay is living a different kind of life in the downtown core of Vancouver, far away from the suburbs. We find her at at a particularly high point—the cafe she has been co-managing has just found acclaim by being written up in a magazine. Mandalay loves her job, her co-worker, that she is responsible for arranging art in the place and becoming known for her skills in curation. Sure, her apartment is tiny and expensive, and her work means she is busy all the time, but Mandalay finds herself fulfilled for the first time in her life, after years spent hitching onto the rides of the men she’s been in relationships with. Which, inconveniently, is the moment that Duane turns up, a man who suits her in so many ways but is unwilling to provide proper emotional ties. But does she want these? Does she need these? What kind of relationship does Mandalay think she deserves?

And then finally, there is their younger brother Cliff, hapless, utterly lacking guile. He’s not stupid though, Cliff, and he knows the problem is mainly other people. So he knows, for instance, not to let people know about his new TV, when he finally saves up from his landscaping job for the one he’s been looking for. He knows that when other people find out he’s got something, they’re only ever going to want to take it, so he keeps to himself. He works hard and has made a comfortable life for himself, and all he wants is to stay out of trouble…but trouble seems to find him. And Hofmann’s depiction of Cliff is one of the most wonderful parts of this book, how fully realized he is, without the cliches often fastened to literary characters lacking in IQ. How canny he actually has to be to get along in the world, and all the tricks and devices he’s figured out that nobody would ever give him credit for. He’s a terrific character.

The novel opens with the three siblings’ different narrative threads, each of which are far apart due to family history and how disparate their circumstances are in terms of life and also of postal codes. The three of them are in touch, but mainly see each other at holidays, can go weeks without a phone call. But when their long lost baby brother finally tracks them down, and then Cliff has an accident that requires him to recover in the relative quiet of Cleo’s suburban house, the siblings begin to come together again. And questions are raised not only about the practical matters of how characters who’ve come from different places can be a family, regardless of their mutual place of origin. But also about the role their past traumas play in the present day, and what those traumas are, exactly. It turns out the history each of them has taken for granted turns out to be more complicated than any of them have imagined. And what does that mean for the future?

I really liked Karen Hofmann’s first novel, After Alice, and was so pleased that What is Going to Happen Next lived up to my expectations—and then some. It’s a novel that’s as original as it is ambitious, and it works, resulting in an all-engrossing visceral reading experience, and I’m recommending it to everyone.

September 5, 2017

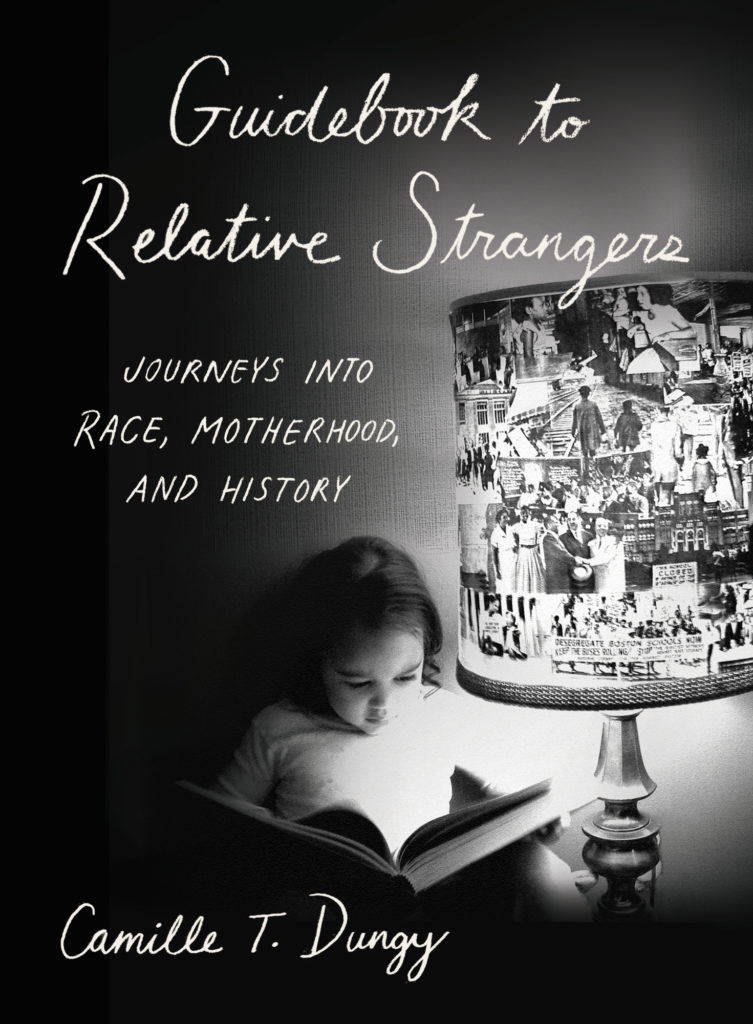

Guidebook to Relative Strangers, by Camille T. Dungy

I can’t remember the last time a book had so strong a hold on me as Camille T. Dungy’s Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys Into Race, Motherhood and History. A book whose force is evident from its opening page, a note of introduction. “When the nation that became the United States was beginning, women writers and black writers needed the endorsement of other people in order to prove their legitimacy,” Dungy writes in her very first sentence. Later in the paragraph: “The essays in the book you are reading are steeped in such history.” Dungy wants to resist this notion that she requires anyone but herself to demonstrate the merit of her work, and yet… She then she goes on to write five pages of the most beautifully written acknowledgements I’ve ever encountered in a book. A remarkable start, and an introduction indeed to Dungy’s expansiveness, generosity, thoughtfulness and ability to understand that two opposing ideas can be true at once.

Guidebook is a collection of essays, but like the best of such things is a journey itself, a whole worth more than its parts which fit so well that they don’t even seem like parts. It begins with an event from Dungy’s not so long-ago past, except that it was a thousand years ago because it was before she became a mother. She was at a writers’ retreat and trying not to become involved in a conversation about how she hadn’t seen the film, The Hours, because she didn’t care about The Hours. In this moment, as is often the case on this retreat, Dungy is the only black person at the table, and is therefore called upon to represent blackness and otherness to the white writers in her company. Which makes her tired—she’s just returned from time in Ghana and the essay contrasts these two experiences and she writes, “Perhaps it would be a more stable world if everyone could experience both the sensation of oneness and otherness a few times in life.” Back at the table, Dungy is assured that her companion doesn’t see her “as a black woman. You’re just who you are.” Which brings the author around to the powerful paragraph that led me to pick up this book in the first place, and certainly the paragraph delivers on everything this paragraph promises:

I am certainly who I am (an ornery individual at the moment) though I take umbrage at the idea of limiting my scope with a word like just when it is used to suggest that I am a simple person. If I may borrow a phrase from the great poet of our early democracy, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” Just in this context erases various complexities and dimensions of my being. There is a danger in refusing to, or tacitly agreeing not to, recognize my black womanness. Black womanness is part of what makes me the unique individual that I am. To claim you do not recognize that aspect of my personhood and insist, instead, that you see me as a “regular” person suggests that in order to see me as regular some parts of my identity must be nullified. Namely, the parts that aren’t like you.

Dungy is a professor, award-winning poet and editor, and devouring her non-fiction (I read this book in a day) put me in mind of Rebecca Solnit and Joan Didion (for style reasons and also San Francisco and California) and Anne Enright’s Making Babies with the perfect exuberance with which she writes about motherhood, and Leslie Jamison for the ways she writes about her body and her experiences with MS. Most of all, however, Dungy writes about language, which itself reveals so many secrets and much complexity. The essay “Bounds” is an incredible consideration of that words many meanings and what their connections tell us about human experience, about Dungy’s daughter’s language acquisition, about what divides us and what connects us, and how so often these two things are one and the same. I ordered this book not long after the terrifying events in Charlottesville, VA, in August, and it’s something to consider the images from the white supremacist rally against Dungy’s short essay about her time living in Virginia where her white friends delighted in bonfires, and she, because of the area’s legacy of racial violence, could only feel fear at the idea and reality of these kinds of events.

Dungy writes about her experiences travelling in America before her daughter turned two, when she was still nursing and could fly on her mother’s lap for free, and about the places they went and how Dungy would be both connected to and divided from the people she encountered, and how her daughter helped to mitigate the distance between Dungy and others. This is a book about the labours of motherhood and academia, and writing, and the ridiculous ways we negotiate these in the 21st century. It’s a book about cities and nature, and the words we use to describe these places, the names we call ourselves and others, and the places motherhood takes us where we never planned on going—I love a line in the essay “Inherent Risk, Or What I Know About Investment” that goes, “I passed the sign for the landmark every time I took the Fruitvale Avenue exist off I-580 on my way home, but I had no idea what it referred to until one day, when Callie still cried constantly unless she was moving, I strapped her into the stroller and walked until I found the place, which is how I started to know some of the things I’ve written here.”

The essay “Bodies of Evidence,” about birdwatching with her two friends who are two of the five black birders in America, so the joke goes; about her daughter’s infatuation with The Little Mermaid; about her own family’s legacy of racial violence; about Dungy spending her adult life trying to delay the onset of the diabetes that plagues her family, only to be diagnosed with MS; “When I am writing, it is always about history. What else could I be writing about? History is the synthesis of our lives;” about being the only person in her second-grade class who voted from Jimmy Carter in a 1980 mock-election; about a visit to a memorial of a lynching that took place in Duluth, Minnesota; about survival, be it through MS or poison oak—or a police officer pulling you over on a dark highway, if one happens to be black; about an article in the New Yorker about inequality, about an eclipse, about shadow. This is one essay. “Sometimes it is easy to draw meaning from the arbitrary order of things.” But of course there is nothing arbitrary about any of this—these essays are masterful. Buy this book now.

August 2, 2017

Annie Muktuk and Other Stories, by Norma Dunning

When I read the article, “What inspired her was getting mad,” about the story behind Norma Dunning’s debut collection, Annie Mukluk and Other Stories, I was not surprised. Acts of justice and revenge factor throughout the book, propelling the stories so terrifically. Dunning wrote her stories in response to ethnographic representations of Inuit people that neglected to show them as actual people, and the result is a book that’s really extraordinary. Because her people are so real, people who laugh, and joke, and drink, and have sex (and they have a lot of sex). Her characters love each other fiercely, family ties are nurtured in spite of obstacles (including residential schools and their legacy) and they all have a great deal of fun playing with the ignorance of the qallunaaq (Anglo-Canadian) and their perceptions of the north.

When I read the article, “What inspired her was getting mad,” about the story behind Norma Dunning’s debut collection, Annie Mukluk and Other Stories, I was not surprised. Acts of justice and revenge factor throughout the book, propelling the stories so terrifically. Dunning wrote her stories in response to ethnographic representations of Inuit people that neglected to show them as actual people, and the result is a book that’s really extraordinary. Because her people are so real, people who laugh, and joke, and drink, and have sex (and they have a lot of sex). Her characters love each other fiercely, family ties are nurtured in spite of obstacles (including residential schools and their legacy) and they all have a great deal of fun playing with the ignorance of the qallunaaq (Anglo-Canadian) and their perceptions of the north.

In “The Road Show Eskimo,” an elderly Inuit woman who found fame as the apparent author of a book about her experiences in the South—except the book was a fraud and it had been written by her white ex-husband—makes money from this endeavour and she even relishes the role she has to play to conform to peoples’ expectations. But on the particular day depicted in this story, the woman is going to take back her identity and use the power she’s been holding all along.

Such power also factors in the story “Husky,” about a HBC Agent who brings his three Inuit wives to Winnipeg where they are all made victims of violent racism—until they aren’t anymore, and the women take matters into their hands in the most fantastic feat of justice.

I loved “Elipsee,” about a man who’s taking his beloved wife out on the land one more time—she’s dying of cancer and this is the one thing left to try, and it actually works, in a beautiful, sad and perfect way, as the couple reconnects with their own history and that of their ancestors. In “Kakoot,” an Inuit man at the end of his life tries to leave this world for the next, which is complicated when you life in an old age home in the south and the spirit of your land and people are hard to come by.

And “Annie Muktuk” is the gorgeous story of two friends, one of whom has fallen in love with the titular character, described as follows:

“What I couldn’t get into Moses Henry’s head was that she just wasn’t Annie Mukluk. She was bipolar. She liked the Arctic and the Antarctic. She played with penguins and the polar bears. Annie Mukluk liked to fuck and she did it with everyone in Igloolik and everywhere else she went. She’d fuck your father, your sister, all your brothers and finish off with your mother. She swung both ways and sideways.”

(This paragraph joins the one about Slutty Marie from Megan Gail Coles’ Eating Habits… as perhaps two of my favourite paragraphs about women with voracious sexual appetites in all of Canadian literature.)

Anyway, the two friends, Moses Henry and Johnny Cochrane are each puzzling out the ways forward in their lives, in a fantastic, ferocious and bawdy novella about love, and brotherhood and friendship. I loved it. In “My Sisters and I,” three amazing women survive their experiences at residential school with their wits and strength, and the punch in the nose at the end of the story is the spectacular and perfectly delivered act of violence. This is justice, which is nice to encounter somewhere, even fictionally, because there’s certainly not much of it in reality. But these kinds of representations of Inuit women are just the beginning…

July 10, 2017

Hunting Houses, by Fanny Britt

Here’s my true and somewhat embarrassing presumptuous confession: if I were a Governor-General’s Award-winning author, translator and playwright (with more than a dozen plays to my name) then Fanny Britt would totally be my Quebecois alter-ego. I started considering this idea when I published the non-fiction anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014, and learned that the year before Britt had published an anthology of essays about motherhood called Les Trenchees, illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault—who had also illustrated Britt’s award-winning graphic novel, Jane, the Fox, and Me. I even bought an ebook version of Les Trenchees, although I can’t read French, but I figured if I wanted to read it hard enough I’d figure out how, although I never did. But no matter now, for Fanny Britt’s thoughts on womanhood and motherhood as expressed in her acclaimed novel Les maisons are now available as Hunting Houses, translated by Susan Ouriou and Christelle Morelli. A novel I read on the first two days of my holiday last week and loved completely, and also I hope there is a fictional world somewhere in which Britt’s protagonist Tessa and Sarah from my novel Mitzi Bytes are sitting in a kitchen having the most delicious gossip.

Here’s my true and somewhat embarrassing presumptuous confession: if I were a Governor-General’s Award-winning author, translator and playwright (with more than a dozen plays to my name) then Fanny Britt would totally be my Quebecois alter-ego. I started considering this idea when I published the non-fiction anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014, and learned that the year before Britt had published an anthology of essays about motherhood called Les Trenchees, illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault—who had also illustrated Britt’s award-winning graphic novel, Jane, the Fox, and Me. I even bought an ebook version of Les Trenchees, although I can’t read French, but I figured if I wanted to read it hard enough I’d figure out how, although I never did. But no matter now, for Fanny Britt’s thoughts on womanhood and motherhood as expressed in her acclaimed novel Les maisons are now available as Hunting Houses, translated by Susan Ouriou and Christelle Morelli. A novel I read on the first two days of my holiday last week and loved completely, and also I hope there is a fictional world somewhere in which Britt’s protagonist Tessa and Sarah from my novel Mitzi Bytes are sitting in a kitchen having the most delicious gossip.

“There’s some solace in thinking your house will live on outside you, like an extension of yourself, a promise renewed no matter the trials or failures, bestowing sudden meaning on sorrow. Personally, I have a hard time swallowing the whole idea because I have no desire to see others blossom where I wilted—but then I’m not that nice a person.”

But then Britt is that kind of writer, I think. The writer who makes you feel as though you’re privy to some incredible intimacy, or even that she’s written her book with the most uncanny regard for the contents of your soul. I am sure I’m not the only reader who’s come away from Hunting Houses imagining that Britt and I have some kind of spiritual connection, that in some actual kitchen we could be terrific friends.

Anyway, it’s always a kitchen, right? Domestic realms. Kitchens and nurseries. Rooms matter, in particular because Hunting Houses’ Tessa is a real estate agent, an occupation that gives her curious access to other people’s lives. Although it’s in the laundry room where the story begins, where Tessa is being shown the house of a new client, Evelyne, whose selling her house due to divorce. “I don’t yet know that I’m at his house,” is the novel’s first sentence, he being Evelyne’s soon-to-be-ex, who Tessa encounters on a subsequent visit. An old flame of Tessa’s, a mostly unrequited seemingly inconsequential relationship, but one that arrives on the tail of adolescence and just before a jarring trauma, so that she never entirely gets over him, Francis. And then suddenly here he is all these years later, and the two of them make plans to meet.

Is she happy, Tessa, in her life? Selling houses becomes a metaphor for the hollowness at her core, a career she came to after a failure to become a professional singer, and then an early voyage into parenthood, which comes to define her. In a way it doesn’t to her husband, Jim, a trombonist, who has achieved a coveted job in an orchestra. But motherhood being not a full enough answer to the question of how a woman spends her time (as I write about in Mitzi Bytes; as Britt writes, “Is Tessa really going to spend the rest of her life working in a bookstore and having babies?”), Tessa requires something more, and so there is real estate. But there is also swimming lessons, and driving her children to school (and fitting awkward projects just-so into the trunk of her car), and Tessa is also in charge of the sweets on sale at her children’s school’s science fair.

“There’s the organizing committee and its numerous meetings, the first one usually held on a dark windy Wednesday November evening during which no one has anything to say about an event to held months later, but it’s the main source of social interaction for some parents, so I go (one out of every three times) since I don’t want to lose my kingdom.”

There is also Tessa’s best friend Sophie, who’s spent ages trying and failing to get pregnant, and memories of their youth together. And Tessa’s feelings about her life and about motherhood are further defined by her relationship to her own mother, which is complicated. Years before when Tessa was small, her mother took Tessa and her brother and fled her small town marriage and world for a single, free but hard scrabbling life in Montreal—and it’s interesting to read about motherhood from the perspectives of daughters whose mothers aren’t 1950s archetypes, a generation skipped. To be the daughter of a generation of women who made the breaks and took the chances, but learned that these kinds of risk aren’t necessarily the answer to every question. That life is much more complicated than that.

With shades of Virginia Woolf and Rachel Cusk in A Life’s Work and Arlington Park (but less annoying), Hunting Houses is the story of a few days in a life, and it also moves in and out of years. It’s a taut read and its momentum comes from Tessa’s voice and the surprising nature of her perspective, and also from the suspense of will-they-won’t-they as she prepares to meet with Francis again. It’s about the unflagging interestingness of other people’s lives and other people’s houses, and the lives we could possibly lead if we came unmoored from our own. “It was the blessed hour when lights go in houses and curtains have not yet been drawn.” Stories, like lit windows, illuminating countless other worlds.

June 27, 2017

Boundary, by Andrée A. Michaud

How about a book that checks all the boxes: an award winner (Governor General’s Award for French Fiction, and the Arthur Ellis Award), a gorgeous translation, a narrative with psychological depth, and a gripping thriller of the sort that summer reads are made of? I spent my weekend with Boundary, by Andrée A. Michaud, so perfectly steeped in summer and suspense, and I loved it—and I have been ardently recommending it to everybody for days now.

How about a book that checks all the boxes: an award winner (Governor General’s Award for French Fiction, and the Arthur Ellis Award), a gorgeous translation, a narrative with psychological depth, and a gripping thriller of the sort that summer reads are made of? I spent my weekend with Boundary, by Andrée A. Michaud, so perfectly steeped in summer and suspense, and I loved it—and I have been ardently recommending it to everybody for days now.

It’s set in a cottage community in Maine, a land that divides two nations, two languages. It becomes a place of in-between where anything is possible during the summer of 1967, the summer of love, the novel’s soundtrack playing Procol Harum and Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds. It’s a novel that’s also set on the border between girlhood and womanhood, two girls—Zaza and Sissy—on the cusp of everything. None of which will transpire, as both girls will be found dead that summer, caught by brutal animal traps hearkening back to the legendary woodsman Pete Landry, long ago found hanged his cabin and still said to haunt the woods. Are the girls deaths nothing more than tragic, stupid accidents, or is something (and someone) much more sinister at work?

If it weren’t already taken, Lives of Girls and Women would be an excellent alternative title for Boundary, which in its consideration of girlhood, friendship and violence, reminded me in the best way of Joni Murphy’s Double Teenage. While the novel is told from multiple perspectives, including from that of Detective Stan Michaud, its primary point of view belongs to young Andree Duchamp, who is young enough to escape much notice but also to notice everything—the exotic lives of the teenage girls, and also the experience of the wives and mothers in the community, who are its bedrock, and the ones who are left behind during the week when the husbands return to the city and whose stories are told with remarkable psychological acuity.