August 15, 2018

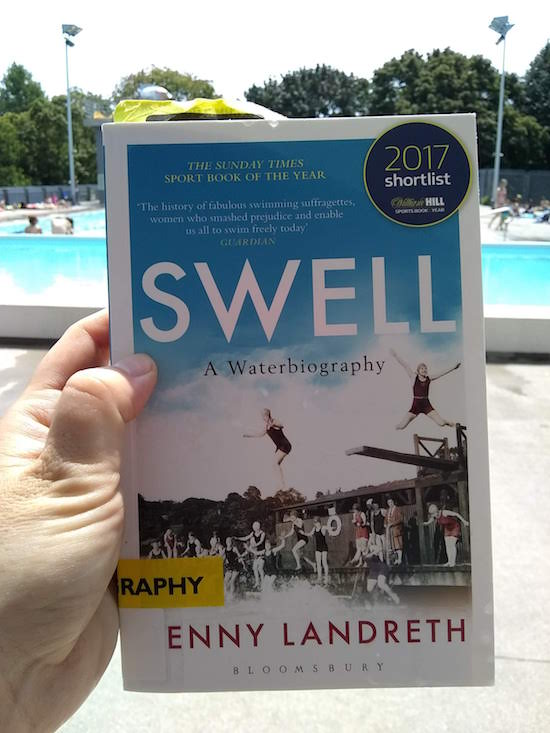

Swell: A Waterbiography, by Jenny Landreth

The gendered nature of swimming is something I think about all the time, although most often when I am sharing a lane with a man who has found taking up ample space by merely having longer limbs than I do unacceptable, and therefore has decided to enhance his lengths with flippers on his feet and paddles on his hands, increasing his chances of making violent contact with my body as he passes me. The women in the pool I swim at don’t do this, and neither do they, as one swimmer in Jenny Landreth’s spectacular book Swell: A Waterbiography does, butterfly up and down narrow lanes driving all other swimmers into the gutter. In her recent book, Boys, Rachel Giese writes about the way that boys are taught to be entitled to public space, as they dominate the basketball courts on the playground, and because I spend most of my time hiding in libraries, I don’t encounter this very much, but it’s in the pool I do. And it all makes me think of the line on the very first page of Swell, which was where I fell in love with this book: “how swimming can be a barometer for women’s equality.” We’ve all come a long way, but still.

Swell is my favourite book I’ve read this summer, a summer that has been all about swimming, in pools and lakes, as both my children are both at pivotal stages in the development of their inner fishes, and we can worry slightly less about the little one drowning. I’ve gone swimming by myself four mornings a week along with the men with the hand paddles and the flippers, and then later in the day we’ve all gone to the public pool and I’ve sat in the shallows and tried not to think about pee as my daughters delighted in turning somersaults over and over again. So yes, Swell was just absolutely perfect.

It’s a book I’d situate as what might happen if Sue Townsend of Adrian Mole fame got together with Elizabeth Renzetti’s Shewed and they decided to have a literary baby that was also a social history of women swimming in England. The result is absolutely delightful, empowering, and so terrible funny in its asides that I kept reading them aloud to the people around me who became very confused about what this book was about exactly. But that’s because it’s about everything, about the history of suffrage, and bathing suits, and public pools, and mixed beaches, and how women used to drown all the time because they weren’t taught to swim, and about how when they decided they did want to learn how to swim, no one could teach them because all the instructors were men and men and women couldn’t possible swim together. It’s about pools where women were accorded very little time for swimming, and it was usually during the day when no one could make it anyway. It’s about women who defied convention (and their mothers!) to become swimming superstars, pioneering the front crawl in England, swimming the English channel, being the first women swimmers in the Olympic games.

Landreth writes, “‘In front of every great woman is another great woman… Women whose lies will change. Some who will take this story, make it their story and push it on to its next pages.”

And of course, Landreth’s own story is part of this book, her “waterbiography”—and she admits to being proud to have coined the term. She grew up in the Midlands, which is kind of a swimming desert—when I lived there I was once so desperate for a swim that I dove in the duck pond on the Nottingham University Jubilee Campus—and was an unlikely candidate to become an avid swimmer for a host of reasons. She writes about learning to swim as a child, about travelling to Greece in her 20s and trying proper swimming for the first time, about lacklustre swimming as part of the 1980s’ fitness craze, about what an awful and unfulfilling thing it is to go swimming with small children—and then about finding her identity as a swimmer once her children were older, and what a thing it is that women can do this at any age. About how empowering it was to learn to call herself a swimmer.

There is indeed something womanly about swimming, in spite of the Michael Phelpses and the men with paddles on their hands. I mean, have you ever heard of a male mermaid? No. And I can’t for the life of me think of a single man who’s swam across Lake Ontario, but I know about Marilyn Bell and Vicki Keith, and Annaleise Carr, a swimming hero for every generation. I have dreams of one day swimming in the Ladies Pond at Hampstead Heath. I used to buy terrifically fancy swimsuits, but lately I’ve become enamoured of my sporty suits, the ones I wear while swimming in the pool in the mornings. Where my favourite swimmer is this woman I’ve never spoken to, but she’s my hero—grey bathing cap (I wouldn’t know her without it) and same bathing suit as mine, a bit stocky, older than I am. And in the pool every morning, she’s the fastest every time.

More on swimming:

- Swimming Holes We Have Known Blog

- Katrina Onstad on public swimming pools

- Nathalie Atkinson’s article in Zoomer Magazine on swimming books (which is where I heard about Swell).

- “Drowning at Midlife? Start Swimming” from the New York Times.

- “Swimming pools are a balm for whatever ails me”

- And a swimming quilt!

August 7, 2018

Sodom Road Exit, by Amber Dawn

I’ve had Amber Dawn’s Sodom Road Exit waiting for me since the beginning of May, when I bought it right after seeing her speak on a panel on genre at the Festival of Literary Diversity. She was fantastic on the panel (along with Cherie Dimaline, David A. Robertson, and Michelle Wan), explaining that Sodom Road is an actual road with an exit off the QEW to get to her hometown of Crystal Beach, on Lake Erie, which was once a thriving resort town with an amusement park famous for its terrifying roller coaster. Her novel is set during the summer of 1990, a year after the amusement park closed and things are officially in decline. Which is when Starla Mia Martin returns to town, driven by debt and desperation to move back in with her mother, and then inadvertently begins to channel a ghost who is powered by relics from the old amusement park, the spirit of a woman who’d been killed in an accident on the roller coaster decades before. But is this a benevolent spirt? Is she helping Starla get back on her feet, or is she only making it worse—and for a good portion of the book, it’s hard to tell. Starla gets a job working at a campground on the graveyard shift, which doesn’t help calm her mind at all, or reduce her propensity for being haunted. And as her connection to the spirit intensifies, Starla’s situation is complicated by the relationships she’s developing in Crystal Beach, in spite of herself—with her boss at the campground, an Indigenous woman who lives there and is struggling to maintain custody of her son, with the former high school classmate who dances at the local bar and with whom Starla might possibly think about entering into a relationship…were she the type of person who did such a thing as have loving relationships, and also if she wasn’t already cavorting with a woman who’s been dead for fifty years.

I’ve had Amber Dawn’s Sodom Road Exit waiting for me since the beginning of May, when I bought it right after seeing her speak on a panel on genre at the Festival of Literary Diversity. She was fantastic on the panel (along with Cherie Dimaline, David A. Robertson, and Michelle Wan), explaining that Sodom Road is an actual road with an exit off the QEW to get to her hometown of Crystal Beach, on Lake Erie, which was once a thriving resort town with an amusement park famous for its terrifying roller coaster. Her novel is set during the summer of 1990, a year after the amusement park closed and things are officially in decline. Which is when Starla Mia Martin returns to town, driven by debt and desperation to move back in with her mother, and then inadvertently begins to channel a ghost who is powered by relics from the old amusement park, the spirit of a woman who’d been killed in an accident on the roller coaster decades before. But is this a benevolent spirt? Is she helping Starla get back on her feet, or is she only making it worse—and for a good portion of the book, it’s hard to tell. Starla gets a job working at a campground on the graveyard shift, which doesn’t help calm her mind at all, or reduce her propensity for being haunted. And as her connection to the spirit intensifies, Starla’s situation is complicated by the relationships she’s developing in Crystal Beach, in spite of herself—with her boss at the campground, an Indigenous woman who lives there and is struggling to maintain custody of her son, with the former high school classmate who dances at the local bar and with whom Starla might possibly think about entering into a relationship…were she the type of person who did such a thing as have loving relationships, and also if she wasn’t already cavorting with a woman who’s been dead for fifty years.

Things get complicated Or even more complicated? Starla, following the instructions of the spirit, has a memorial gazebo erected out of materials from the amusement park, and people begin to travel from miles around to witness her communing with the dead and perhaps channelling their own lost loved ones. But the toll of these experiences and the burden of Starla’s connection to the spirit become too much for her to carry and her mental and physical health begin to suffer, so much so that soon the people who love her are frightened for her life.

I picked up this book because I was intrigued by the setting, and also so fascinated by Dawn’s remarks on genre and the idea of the novel as a container for a ghost story. And I was a little bit intimidated to finally start reading it because a) it had the word “sodom” in the title, b) it was a solid brick of a book and was I ready to commit to that many pages, and c) in order for the premise to work, it would have to be a really, really exceptional novel. Which, it turns out, it is. I loved this novel. We were camping the weekend before last, which isn’t always the best place to be reading, because there are bugs, and chores, and children setting themselves on fire, but all these things took a back seat as I read 300 pages of this book in two days, and came home and read the rest once the laundry was done, because it really was that compelling, so masterfully crafted. It’s a perfect gripping amazing summer read, but it’s also underlined with substance—the stakes are real here. I absolutely loved it.

July 2, 2018

Florida, by Lauren Groff

It continues to be one of my favourite serendipitous things, reading a short story to realize I’d read it before, long ago, in an entirely different context. I wrote about this when I finally read Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories in 2012 and realized I’d read “Celia Behind Me” two decades before in my Grade 12 English textbook: “And I realized that I’d read this story before, more than once. It was so strangely familiar, like something I’d known in a dream, but somebody else’s dream.” I remember it also happening when I read Lauren Groff’s “L. DeBard and Aliette” in her first story collection Delicate Edible Birds in 2009, and I realized I’d read the story in The Atlantic in 2006, that it was the first thing by Lauren Groff I’d ever read—before The Monsters of Templeton, even. Before I even realized there was such a thing as Lauren Groff, who has since gone on to become my very favourite writer.

I love “rediscovering” these stories for so many reasons, for the way it suggests the architecture of my mind is infinite dusty corridors and who knows what lies around the next corner, and also for how it underlines that nothing ever goes away. That those dusty corridors are lines with rooms that are full of stuff, everything I’ve seen or heard or thought or read, and how it’s still there, all of it, even if not immediately accessible.

Midway through Florida—which is a book I’d picked up with more expectations than previous works by Groff, but also with the expectation that I was to suspend all expectations because she never does the same thing twice—I came upon her story “Above and Below.” And partway through that story I realized I’d read this one before as well, in The New Yorker in 2011. And I remember not liking it. This was before Arcadia, before I properly understood the breadth of Lauren Groff’s literary ambition, of her range. This was before the world fell apart as well, after the global economy melted down in 2008 but in that quiet period where it seemed like it all might be okay, and those of us who didn’t live in places like Florida might have been fooled into thinking that progress was an ongoing story. I remember that I just didn’t see the point.

In the context of 2018 though, of this book itself, the story reads very differently to me. I also found it interesting to think about the story in the context of Arcadia, which was about a community that comes together and then falls apart, as the society depicted in “Above and Below” also seems to be unravelling, or at least it is for the protagonist—I see how it fits into her oeuvre in a way I wasn’t able to appreciate at the time. And it certainly does fit into this collection, which is of stories in which dread is creeping, danger lurks, children are stranded alone on islands, and the possibility that a sinkhole might open at any time beneath you is not especially remote.

Florida is a locality of extremes—I am frequently grateful for living smack-dab in the middle of the continent, as immune as one could possibly be from hurricanes, earthquakes, or alligators. When I hear stories like that of a sinkhole that swallowed an entire house, I think to myself, “Well, that’s a Florida story,” and go on with my day. Although if I’ve learned anything in the last few years, it’s that what’s going on at the edges, in the margins, has deeper ramifications than I ever really realized. That a story like “Above and Below,” about a character who loses everything and just keeps going—it seems less marginal now than it did in 2011.

I like Florida for how it’s a book as well as a collection of stories. I like stories, but when I pick up a book, a book is what I want, for there to be themes and connections that tie it all together. Not that the stories be linked, necessarily, but that they inform each other. Context matters. I want a story collection to be a book that’s capable of being grasped and understood as a whole. Which is the whole reason I’d be shaking this one emphatically and imploring you to read it: Florida! It’s so good. It will break your heart about this miserable perilous world, but you’ll also love that world a little bit more because this incredible book is in it.

June 19, 2018

Ayesha At Last, by Uzma Jalaluddin

True confession: I’m not a huge fan of Jane Austen and think Colin Firth is kind of drippy, so while the Pride and Prejudice connections to Uzma Jalaluddin’s debut novel Ayesha at Last might get some readers going, it was never going to be me. But thankfully Jalaluddin doesn’t stop at Austen while giving her novel its literary underpinnings—her main character Ayesha’s grandfather is an English professor who peppers his speech with allusions to Shakespeare and he’s the one who points out the similar framework between Ayesha’s own story and many of Shakespeare’s plays—”Shakespeare enjoyed a good farce. Separated twins, love triangles and mistaken identity were his specialty. Yet it is through his tragedies that one learns the price of silence.” He implores his granddaughter, “Promise you will always choose laughter over tears. Promise you will choose to live in a comedy instead of a tragedy.” But any life, of course, will always be a bit of both.

True confession: I’m not a huge fan of Jane Austen and think Colin Firth is kind of drippy, so while the Pride and Prejudice connections to Uzma Jalaluddin’s debut novel Ayesha at Last might get some readers going, it was never going to be me. But thankfully Jalaluddin doesn’t stop at Austen while giving her novel its literary underpinnings—her main character Ayesha’s grandfather is an English professor who peppers his speech with allusions to Shakespeare and he’s the one who points out the similar framework between Ayesha’s own story and many of Shakespeare’s plays—”Shakespeare enjoyed a good farce. Separated twins, love triangles and mistaken identity were his specialty. Yet it is through his tragedies that one learns the price of silence.” He implores his granddaughter, “Promise you will always choose laughter over tears. Promise you will choose to live in a comedy instead of a tragedy.” But any life, of course, will always be a bit of both.

In Ayesha at Last, the shenanigans begin when Khalid, a very conservative Muslim, takes an interest in the woman who lives across the street in his new neighbourhood, which sounds like no big thing, except Khalid is devoutly uninterested in women in general because he’s waiting for his mother to arrange his marriage. He also refuses to shake his new boss’s hand, because touching women goes against his beliefs, which causes his boss to turn against him with brutal results. And then later at a meeting at his mosque to help organize a youth conference, he finds himself face-to-face with the woman he’s been watching…except he thinks she’s her cousin, and attraction sparks between them before some inevitable mishaps ensue.

And the woman, of course, is Ayesha herself, who’s starting a new career as a teacher to pay back a debt to her uncle, although she’d rather be writing poetry or doing anything but standing in front of a classroom of high school students. She gets roped into organizing the youth conference because of her flighty cousin Hafza who is currently entertaining several potential husbands (mostly because she’s longing to kickstart her career as an event planner, and feels her own wedding would be the best place to start). Her best friend is Clara, who works with Khalid (in HR, which doesn’t make it easy when Khalid’s boss goes on her vindictive rampage). And Ayesha has absolutely no interest in Khalid, with his robes and untrimmed beard and archaic ideas of what it means to be a proper woman or a proper Muslim. But when the two of them are together, something happens and the force is unstoppable.

There are a couple of instances of awkward maneuvering at the beginning of the story to get all the players in their proper places, but once the story starts, Ayesha At Last becomes very difficult to put down. Neither Ayesha nor Khalid is a perfect human, and at first they tend to bring out each other’s worst tendencies, and then there’s the matter of Khalid not knowing Ayesha’s actual identity, and when he gets to engaged to the actual Hafsa (thinking she is Ayesha) it all begins to go wrong. The story is further complicated with the involvement of Khalid’s sister, who was sent away to India years before under dubious circumstances and Khalid is too afraid of his mother to ask the right questions about what happened to her, and also Ayesha’s own mother who is bitter about marriage after her husband’s mysterious death, so Ayesha doesn’t have the answers in her own family history either. And what is the role of love then, and is it a blessing or a curse, and does it have a role at all in communities that adhere to traditional values?

Ayesha at Last is completely a delight, more farce than tragedy, but with depth and poignancy and a willingness to grapple with big questions. It’s a smart and assured debut that is deliciously devourable and deserves space on everyone’s reading list this summer.

June 13, 2018

An Ocean of Minutes, by Thea Lim

So the book whose spell I’m currently under is Thea Lim’s An Ocean of Minutes, which is just another one of your usual time travel/flu pandemic/post-apocalyptic fare. (Ambitious, yes?) It’s 1981, and Polly and her boyfriend Frank are stuck in Texas where he comes down with the illness that will kill him unless they can secure life-saving treatment. And the only way to pay for this treatment is possible is for Polly to sign a contract to travel into the future and becoming a bonded worker for TimeRaiser, the company that invented time travel and which is now bringing workers from pre-pandemic America into the future to help rebuild the nation. So Frank and Polly agree to meet again in 1993 and she departs from 1981 at the Houston International Airport: “The only thing remaining of familiar airport protocol is the logistical thoughtlessness of the curb: once you reach it, the line of unfeeling motorists waiting behind you means only seconds to say goodbye.” Twelve years. “It’s a quarter of a blink of an eye in the life of the universe.”

So the book whose spell I’m currently under is Thea Lim’s An Ocean of Minutes, which is just another one of your usual time travel/flu pandemic/post-apocalyptic fare. (Ambitious, yes?) It’s 1981, and Polly and her boyfriend Frank are stuck in Texas where he comes down with the illness that will kill him unless they can secure life-saving treatment. And the only way to pay for this treatment is possible is for Polly to sign a contract to travel into the future and becoming a bonded worker for TimeRaiser, the company that invented time travel and which is now bringing workers from pre-pandemic America into the future to help rebuild the nation. So Frank and Polly agree to meet again in 1993 and she departs from 1981 at the Houston International Airport: “The only thing remaining of familiar airport protocol is the logistical thoughtlessness of the curb: once you reach it, the line of unfeeling motorists waiting behind you means only seconds to say goodbye.” Twelve years. “It’s a quarter of a blink of an eye in the life of the universe.”

But the process is not straightforward (and there have been rumours about TimeRaiser; plus Polly is one of the few skilled workers—an upholsterer—on the journey, and most of her fellow travellers are women Polly thinks might be Mexican, women who don’t speak English, who are even more desperate than she is) and Polly arrives not in 1993, but in 1998, and in a reality nothing like she’d expected. The pandemic has destroyed infrastructure and industry, societal order has collapsed, and the only hope for Texas is health-tourism for the affluent, and Polly will be employed refurbishing furniture for the new resorts because there are no means to manufacture new things. She’d last seen Frank in 1981, just days ago, and then weeks, then months—but it’s been seventeen years for him in a world that’s become a nightmare. Will he even be waiting for her? And if he is, how will she even find him?

There is nothing straightforward about the passage of time, which is why stories about defying chronology through time travel continue to fascinate, and why a telling a story outside of chronology can add such richness to a text (i.e. how Lim’s novel moves back and forth between Polly and Frank’s life in Buffalo from 1978-1981, and to Polly’s journey alone in 1998 Galveston). What it means too that the future Polly travels to in An Ocean of Minutes is set twenty years in our past—historical speculative fiction? And the metaphor that the seventeen years Frank has to wait is but moments for Polly—but isn’t time like that? And isn’t love? How long does one wait? How far does love go?

The people Polly encounters in 1998 are ruthless and awful, which is probably why they’ve survived, but at what price? There is no beauty in this craven new world, in which workers are slaves to the TimeRaiser corporation. Polly enjoys brief moments of connection with the people she encounters, but many of them end up betraying her—mostly to save themselves, or boost themselves, at least. She ends up losing her privileged job and accommodations, and going to live among the women she’d come across at the beginning of her journey, working to cut tiles for swimming pools. And although everyone she encounters has stories of people they were to expecting but failed to be reunited with, Polly refuses to give up on Frank, and it seems like she’s keeping the faith for everyone.

There’s so much going on this book, including passages of wondrous prose and attempts to answer the question of where love goes when it’s over. What are we do with memories? And what about mementos? Early in their relationship, Polly wonders by Frank’s tendency to keep things, souvenirs of their love—does he think their love will end, she wonders? Does he hold on things because of a lack of faith? And yet even Polly longs to preserve their perfect moments, just to hold them. And yet the hours, the minutes, the seconds—they just go and go and go. So is it remotely reasonable to expect love to be a thing that stays the same?

I had to know what happened, so I kept reading, reading, gripped. But (unusual for me) I didn’t flip to the end, just to check. I didn’t want spoilers. I wanted to find out what would happen, but all in good time, and I had faith in Lim’s storytelling—so I held on, and was so impressed by the extent of the allegory, about race and gender, migration, capitalism, environmental and the perilous balance of so much that we take for granted.

I loved this book, and how it turns another time into another country, but doesn’t it always seem that way? So far away, and yesterday, and it’s as though you could almost get back there, and you nearly know the way.

June 4, 2018

The Female Persuasion, by Meg Wolitzer

“And didn’t it always go like that–body parts not quite lining up the way you wanted them to, all of it a little bit off, as if the world itself were an animated sequence of longing and envy and self-hatred and grandiosity and failure and success, a strange and endless cartoon loop that you couldn’t stop watching, because, despite all you knew by now, it was still so interesting.” –Meg Wolitzer, The Interestings

“And didn’t it always go like that–body parts not quite lining up the way you wanted them to, all of it a little bit off, as if the world itself were an animated sequence of longing and envy and self-hatred and grandiosity and failure and success, a strange and endless cartoon loop that you couldn’t stop watching, because, despite all you knew by now, it was still so interesting.” –Meg Wolitzer, The Interestings

I’m still not resolved on what to make of Meg Wolitzer’s latest novel, The Female Persuasion, and how to write about it here, and so I’ve decided to just go for it and see if I can work it out by doing—and all the better if I manage to get it done before I have to go fetch my children in 45 minutes. I loved this novel, but I don’t know how to grasp it. It doesn’t have handles. Its narrative isn’t a line, and it’s stories packed inside of stories, and also a series of waves that keep coming to wash up on shore. Most writers create a narrative, but Wolitzer creates a universe, dense and rich, and its difficult to parse out the story. By which I mean that it’s difficult to parse out just one.

Last week we received a message from our children’s school of a sexual assault of two children in our neighbourhood, and I’m thinking of starting a campaign for better street lighting, not for safety per se, but instead because we’re running out of room on the lampposts we currently have for posters of all the men wanted for assaulting women on our streets. All this is happening in light (or lack thereof) of the misogynistic van attack a few weeks back, and the weight of this is heavy, and when I read the email I literally fell down weeping. I’m so tired of this, of the backlash and misogyny, that it’s considered “political” for a person to profess to caring about gender equality, when there’s an active movement to restrict women’s reproductive choices, and that there continue to be people who don’t think we need feminism.

“‘It’s like we keep trying to use the same rules,” Greer said, “and these people keep saying to us, ‘Don’t you get it? I will not live by your rules.'” She took a breath. “They always get to set the terms. I mean, they just come in and set them. They don’t ask, they just do it. It’s still true. I don’t want to keep repeating this forever. I don’t want to keep having to live in the buildings they make. And in the circles they draw. I know I’m being overly descriptive, but you get the point.”‘ —The Female Persuasion, p. 447.

“‘I assumed there would always be a little progress and then a little slipping, you know? And then a little more progress. But instead the whole idea of progress was taken away, and who knew that could happen, right?” said this vociferous woman.’ —The Female Persuasion, p. 438

“Because our history is constantly overwritten and blanked out…., we are always reinventing the wheel when we fight for equality.” —Michele Landsberg, Writing the Revolution

I mean, on one hand this is a book about what happened when second-wave feminism marched into the twenty-first century, about what happens when feminism meets capitalism, it’s about sexual assault, and friendship, and betrayal, and the possible inevitability of the betrayal. “Possible,” because I’m not sure exactly. This novel is not a polemic, a treatise, but more of an interrogation…of everything. It’s also about coming of age, and getting old, and having ideals, and then losing them. It’s about compromise, about the necessity and danger of. It’s about making friends with one’s worst tendencies. Small towns and big cities. It’s telescopic, and kaleidoscopic too, the story of just a few years in the life of Greer Kadetsky who is transformed by an encounter with famous feminist Faith Frank at her middling college one night in the early twenty-first century. Greer ends up working for Faith’s feminist foundation, and choices she makes in her professional life complicates her relationship with her best friend and her boyfriend. And the narrative takes in both these characters too, as well as Faith Frank, pitching us forward and backward through decades, these same stories that keep happening over and over again.

The Female Persuasion does not have the answers, and reminded me of one of my favourite books about feminism, Unless, by Carol Shields, which similarly interrogates one’s certainties and dares to suggest its protagonist might be wrong. Though not entirely, or perhaps it’s more that right and wrong don’t quite matter, that the world and life itself is too textured for anything as straightforward as binaries. Or for anything like a single narrative thread, either, but instead there is noise, cacophony, as brilliant and loud as the cover of this splendid novel.

May 28, 2018

Sharp, by Michelle Dean

I put Michelle Dean’s Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion on hold at the library as soon it was available, and then a bought the first copy I saw for sale at a bookstore because I just couldn’t wait. The next day a review copy arrived from the publisher, and then three days after that I got the call that my library hold was in, and by this point my children were saying, “Not that book again!” But if ever a title should be ubiquitous, this would be the one. I’ve never read a book quite like Sharp in all my life, and I’m pretty sure you haven’t either.

So here it is: this is not a book about women who were outliers, a sideshow project. Yes, the women profiled in Sharp were exceptions to the rule, which is still true and mainly that people aren’t all that interested in what women have to say. But it’s that history tends to be chronicled through the experiences of men that gives us the idea of these women being on the margins, not the history itself. As Dean writes in her preface: “Men might have outnumbered women, demographically. But in the arguably more crucial matter of producing work worth remembering, the work that defined the terms of their scene, the women were right up to par—and often beyond it.” So that you can you write a history of twentieth-century criticism, and just skip the men altogether, and still end up with a rich and engaging 300 pages comprising fullness.

Though no doubt most of these woman would bristle at being placed in such a group, as these were usually women who resisted groups altogether. Many of them hated each other, though there were some surprising friendships as well (Mary McCarthy and Hannah Arendt!). None of them were “speaking for women,” either, but instead were human people who expressed ideas about things, and sometimes they were wrong, which for women especially is a perilous endeavour. Most of them challenged notions of feminism and sisterhood as well, but then what else would be expect critics to do?

I will be honest: I’ve been ambivalent about the value of criticism for the past few years, and Sharp doesn’t totally assuage that. Social media has done a good job of putting me off opinions altogether, and has me second-guessing whether mine are really worth sharing. “Who cares?” is also a question worth asking, and always has been—and even with these famous critics, the answer is usually “most people don’t.” A lack of outcry about the disappearance of platforms for reviews from anyone except the reviewers only underlines this. Nora Ephron, Joan Didion and Susan Sontag, for example, are best known today not for their criticism. It also strikes me as a very male thing, definitiveness and ranking, like those guys on twitter demanding you show them your source. Why would a woman even bother? (At a certain point in their careers, many of these women no longer did.)

But a good reason to bother is for the richness that women’s voices, in all their diversity, add to the critical culture, I suppose. Dean is forthright about this in her preface when she writes that understanding what made these women who they were is most important because of how much we need more people like them.

May 15, 2018

In Search of the Perfect Singing Flamingo, by Claire Tacon

Everywhere you go, you’ll hear somebody complaining about how political correctness is ruining literature, how authors don’t have the freedom to tell the stories they choose, and what a pity it is that these days there’s so much we’re not allowed to say. To which I would reply for a request for specifics: Please, what it is it that you’re no longer permitted to say? And if the answer is that one time you wrote this thing and people on the internet got angry about it: that is not the same thing. As a writer, and a purveyor of language, you really ought to know the difference. Further, if you’ve been reading as much as I have, you’ll be assured that literature is richer than its ever been, as it’s being expanded, enlivened, and including stories and voices we haven’t heard before. With such boundlessness, there’s absolutely no story you’re not permitted to tell—and long as you ensure that you’re telling it with utmost excellence. For which Claire Tacon’s second novel, In Search of the Perfect Singing Flamingo, absolutely sets the standard.

Everywhere you go, you’ll hear somebody complaining about how political correctness is ruining literature, how authors don’t have the freedom to tell the stories they choose, and what a pity it is that these days there’s so much we’re not allowed to say. To which I would reply for a request for specifics: Please, what it is it that you’re no longer permitted to say? And if the answer is that one time you wrote this thing and people on the internet got angry about it: that is not the same thing. As a writer, and a purveyor of language, you really ought to know the difference. Further, if you’ve been reading as much as I have, you’ll be assured that literature is richer than its ever been, as it’s being expanded, enlivened, and including stories and voices we haven’t heard before. With such boundlessness, there’s absolutely no story you’re not permitted to tell—and long as you ensure that you’re telling it with utmost excellence. For which Claire Tacon’s second novel, In Search of the Perfect Singing Flamingo, absolutely sets the standard.

In her novel, Tacon tells the story of Starr, a woman with Williams Syndrome, who has learning challenges and special needs. She also gives voice to Darren, a lovelorn Chinese-Canadian teenager who’s working as a mascot at Frankie’s Funhouse (basically Chuck E. Cheese) in the months before heading to university to study engineering. And Starr’s father, Henry, who is devoted to his daughter, whose love of Frankie’s Funhouse led to his job there repairing animatronic musicians and servicing pinball machines. Henry has even installed a Frankie’s Funhouse set in his basement for Starr’s entertainment pleasure, constructed out of decommissioned machines. And it’s when he learns via an online ad that the one piece he’s missing—Fanny Feathers, the flamingo in cowgirl regalia—is for sale not far from Chicago that he decides to embark upon a road trip with Starr and also with Darren, who’s got a plan to win back his girlfriend at ComicCon.

This is very much a novel about the difficulties of navigating the system as the parent of a disabled adult, the challenges of finding these adults meaningful work, supporting them in independent living situations, and accessing the resources so that parents don’t have to do all this work on their own—except usually this ends up being the case. Starr herself is one of several first-person narrators, so we also see the situation from her point of view as well, her daily joys and frustrations, the challengers of getting along with her roommate and with work colleagues, and how she works to deal with her challenges and anxieties, and with her parents’ expectations. Which are the same challenges that Darren is facing, actually, and also Starr’s younger sister, Melanie, who has always received less attention from her father than Starr has. And Melanie had struggles of her own—she’s trying to get pregnant, and fears a chromosomal abnormality, and what do these fears say about the fact of her sister’s existence? How will Henry react when he learns what Melanie is going through? And what have nearly thirty years of focussing on Starr meant for Henry’s marriage? He’d go to any length to care for his eldest daughter, but can he say the same thing about his wife?

I loved this book. A novel with this many first-person points of view is an ambitious one, but Tacon lives up to the challenge. She gives each of her characters such rich and rewarding back-stories, occupations, and preoccupations—each one enough to fill a book on its own. And as the story progresses, it becomes clear how connected everything is, how multifaceted the symbolism is. This is not a book about Starr, about disability, about a road trip, about an animatronic rat—but instead, it’s about relationships and intersections, and the incredible interconnectedness of all our lives and the things we love, and the ramifications of our behaviour on others that we might fail to consider. It’s about making safe spaces in the world so that Henry can send Starr out into it with assurance that she is valued and included. It’s a novel about trust, in ourselves, in society, and each other. And it’s a triumph.

April 24, 2018

It Begins in Betrayal, by Iona Whishaw

Oh my gosh, I am in love. I’ve been noting Iona Whishaw’s Lane Winslow mystery series since the first title came out in 2016, most because of the spectacular cover design. But it wasn’t until Friday that I’d actually had a copy in my hands—her latest, It Begins in Betrayal —and started reading. Two days and 360 pages later I finally put the book down an unabashed Lane Winslow/Iona Whishaw convert. The book was brilliant! Absolutely in the spirit of Dorothy Sayers’ Harriet Vane/Peter Wimsey mysteries, but smart and fresh in its own right. For lovers of cozy mysteries and British police procedurals—there’s even a murder investigation in which evidence includes fragments of a broken tea set—this title will not disappoint. But of course there are three more in the series before it, so maybe go back to the start?

Oh my gosh, I am in love. I’ve been noting Iona Whishaw’s Lane Winslow mystery series since the first title came out in 2016, most because of the spectacular cover design. But it wasn’t until Friday that I’d actually had a copy in my hands—her latest, It Begins in Betrayal —and started reading. Two days and 360 pages later I finally put the book down an unabashed Lane Winslow/Iona Whishaw convert. The book was brilliant! Absolutely in the spirit of Dorothy Sayers’ Harriet Vane/Peter Wimsey mysteries, but smart and fresh in its own right. For lovers of cozy mysteries and British police procedurals—there’s even a murder investigation in which evidence includes fragments of a broken tea set—this title will not disappoint. But of course there are three more in the series before it, so maybe go back to the start?

From where I dove in mid-action, however, it was easy to find my bearings. The novels are set in BC’s interior during the 1940s, and by this fourth title ex-British Spy Lane Winslow who retired to Canada after a tumultuous war is in the throes of love with Police Inspector Frederick Darling—there is a reference to the first time they met when he arrested her. There’s a lot going on here—a woman’s body has been discovered in a remote area with suspicious injuries, obviously murder. But before Darling is able to investigate, he’s called away for a meeting with a mysterious government agent asking questions about the downing of his Lancaster bomber four years before in 1943, an event that killed two men in his crew. And the questions he’s being asked are not so straightforward—turns out Darling is about to be charged with murder, a hangable offence.

Thankfully Darling has Lane Winslow in his corner, with her wits, savvy, and intelligence connections. When he’s summoned to London and put in jail, she follows across the ocean to find out more about this vast conspiracy that’s engulfed Darling and his reputation—and can’t help turning up contacts with people from her espionage days whom she’d fled to Canada in hopes of ever avoiding. Could what’s happening to Darling have something to do with her after all? And is she willing to put her own life on the line to save him by travelling into Berlin to spy on the Soviets? If she does, will it even work?

As Darling waits in jail, and Lane works with his lawyer to figure out the real story of what’s happening, Darling’s subordinate back home is at work solving the murder of the woman in the woods, which also has ties to the woman’s family in England and her sister who’d been jilted decades before, and he and Lane assist each other via a couple of rare and miraculous transatlantic phone calls, thereby weaving this wide-reaching story neatly together. And it was such a pleasure to read it, the humour, the intelligence, the underlying feminism. Lane on the world of espionage: “…she was beginning to think the entire enterprise was run by a group of men who had never advanced past the age of thirteen.” The writing was wonderful, the plotting rock-solid, and I adored these characters. Can’t wait to delve into the backlist and discover what I’ve been missing.

April 17, 2018

1979 and That Time I Loved You

Ray Robertson’s new novel, 1979, is set in Robertson’s hometown, Chatham, ON, the story Tom Buzby, of a small town paperboy who once come back from the dead and now everybody thinks he must have some uncanny knowledge of the world and its workings. Which he does, actually, but in a more practical sense than assumed, the way he’s privy to glimpses of private lives, and wise to the cycles and seasons of the town and its residents. He’s not sure either why everybody thinks he’s got access to wisdom, but that’s because he takes his point of view for granted, his unique perspective on ordinary lives, and the fact that there is really no such thing.

Ray Robertson’s new novel, 1979, is set in Robertson’s hometown, Chatham, ON, the story Tom Buzby, of a small town paperboy who once come back from the dead and now everybody thinks he must have some uncanny knowledge of the world and its workings. Which he does, actually, but in a more practical sense than assumed, the way he’s privy to glimpses of private lives, and wise to the cycles and seasons of the town and its residents. He’s not sure either why everybody thinks he’s got access to wisdom, but that’s because he takes his point of view for granted, his unique perspective on ordinary lives, and the fact that there is really no such thing.

Full disclosure: not a long happens in this book. Tom dies and comes back from the dead before the story starts, which is also when his mother, a former stripper turned religious zealot, runs off with the pastor, leaving her tattoo-artist husband to care of Tom and his older sister Julie. There’s a simmering tension involving Tom’s dad finally buying his own property, and the destruction of a local building to make way for a downtown mall, but otherwise it’s Tom on his paper-round, listening to his sister’s records, hanging out with his friends, thinking about his mother, checking out the books at Cole’s, and trying to impress an older girl by lying and telling her he’s read Fear of Flying. All of these characters are richly and sympathetically imagined, and realized.

It might be a two hour drive from Chatham to Wingham, but I still got an Alice Munro vibe from Robertson’s small town scenes, and this was underlined by the “newspaper stories” that are scattered through the novel. Imagined stories (‘Young Woman Finds Ontological Comfort in New Pair of Pants:’ “When I Look at Them, They Remind Me of Who I am”; ‘Man Grows Old and Cranky:’ “I Knew it Happened to Everyone, but Somehow I Thought in My Case There Might Be an Exception”; ‘Man Found Dead in Next-Door Neighbour’s Swimming Pool:’ “I didn’t Necessarily Want to Die, but I Didn’t Want to be Alive Either”) providing readers with access to the inner lives of the people who are secondary characters in Tom Buzby’s own tale, giving answers to questions that Tom does not yet have the age and experience to be asking—although he’s already haunted by a sense that they’re coming.

The book is rich with allusions to literature and music, and one reference specifically informs the project, the poetry collection Spoon River Anthology, by Edgar Lee Masters, which narrates the epitaphs of residents of a small town. Robertson’s take with the newspaper stories is similar in approach, and connects with Tom’s job (and downtown circuits) in a meaningful way. The result is beautifully crafted, a rich and textured perspective of small town life, a nostalgic journey that resonates with the world of today.

When I picked up Carrianne Leung’s new book next, That Time I Loved You, it was purely a coincidence, and I wasn’t expecting a connection. Until the first paragraph, of course: “1979: This was the year the parents in my neighbourhood began killing themselves. I was eleven years old and in Grade 6. Elsewhere in world, big things were happening. McDonalds introduced the Happy Meal, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran and Michael Jackson released his album Off the Wall. But none of that was as significant to me as the suicides…”

When I picked up Carrianne Leung’s new book next, That Time I Loved You, it was purely a coincidence, and I wasn’t expecting a connection. Until the first paragraph, of course: “1979: This was the year the parents in my neighbourhood began killing themselves. I was eleven years old and in Grade 6. Elsewhere in world, big things were happening. McDonalds introduced the Happy Meal, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran and Michael Jackson released his album Off the Wall. But none of that was as significant to me as the suicides…”

These two books are excellent companions, perfect contenders for “If you like this, read…” pairings. Instead of small town Ontario and the past meeting the future, Leung is chronicling the suburbs and the possibility of escaping the past. The setting is Scarborough, where brand new houses with their leafy lawns on winding streets represent fresh starts, new beginnings for the immigrant families who imagine they’ve finally arrived after years of struggle. There’s even a kid with a paper route, Josie, who’d inherited the route from her big brother: “Josie loved her routine and the sense of purpose her job gave her. She loved collecting the money at the end of the week from the neighbours, who often slipped her cookies, candy or even a tip.”

Although the centre of this novel is Josie’s best friend June, another first-generation Chinese-Canadian who revels in the expansiveness and freedom of her childhood, playing outside with her packs of friends until the streetlights come on. Like Tom Buzby, June has her eye on things, and she’s got surprising insight into the lives of her neighbours, although she doesn’t understand everything she learns either—least of all, why there’s been a suicide epidemic, and whose parent was going to be next?

A novel in stories is a perfect container for this book about the suburbs, every chapter a different house on the street. Open the door and go inside to find a different story, a closet full of secrets, a peek out the window to a new view of the street. The Portuguese housewife who is tired with putting up with her abusive husband; the young Italian-Canadian wife who has moved to Scarborough away from downtown, and who longs for a baby that doesn’t come; the neighbourhood social butterfly who is secretly a thief, and whose habits eventually get found out by her neighbours. Plus June’s friends, sweet and effeminate Nav, Darren whose academic potential is undermined by a racist teacher, and Josie, whose uncle is sexually abusing her. As with Robertson and the news articles, Leung’s structure permits her to include a wide range of different voices, and to suggest there is no such thing as a central narrative, but instead to shine a light on these remarkable places where stories intersect.