November 21, 2018

Lady Franklin of Russell Square

There is such a thing as a “[John] Franklinophile,” and I am not one, but still, Erika Behrisch Elce’s novel Lady Franklin of Russell Square delighted me. Written as a series of items discovered in old scrapbooks at Jane Franklin’s childhood home years later by a charwoman, the novel comprises news clippings of stories concerning the search for Franklin, who was presumed missing in late 1847, and also letters Lady Franklin had written for her husband from 1847 to 1857, the years during which went from imminently awaiting her husband’s homecoming to a gradual acceptance that he was not coming back. Not that she ever gives up home completely—she continues to use whatever money she can access to purchase ships and send out search parties, and she continues to engage the government in Britain to continue their search for Franklin’s party, and she solicits aid from abroad as well. No, she is not content to be “the Penelope of England,” as she was called in the press, and she doesn’t go for needlecraft. Instead, she consults maps with the same fervour her explorer husband must have (and the reader gets a sense that they were well matched in their thirsts for adventure), and reads the papers, and lobbies the government, and spends her time among the flowers of nearby Russell Square, with whose gardener she has developed an affinity.

There is such a thing as a “[John] Franklinophile,” and I am not one, but still, Erika Behrisch Elce’s novel Lady Franklin of Russell Square delighted me. Written as a series of items discovered in old scrapbooks at Jane Franklin’s childhood home years later by a charwoman, the novel comprises news clippings of stories concerning the search for Franklin, who was presumed missing in late 1847, and also letters Lady Franklin had written for her husband from 1847 to 1857, the years during which went from imminently awaiting her husband’s homecoming to a gradual acceptance that he was not coming back. Not that she ever gives up home completely—she continues to use whatever money she can access to purchase ships and send out search parties, and she continues to engage the government in Britain to continue their search for Franklin’s party, and she solicits aid from abroad as well. No, she is not content to be “the Penelope of England,” as she was called in the press, and she doesn’t go for needlecraft. Instead, she consults maps with the same fervour her explorer husband must have (and the reader gets a sense that they were well matched in their thirsts for adventure), and reads the papers, and lobbies the government, and spends her time among the flowers of nearby Russell Square, with whose gardener she has developed an affinity.

I loved this book. The letters are funny and smart, and sometimes angry and disappointed, and give the reader a rich perspective on this nineteenth-century woman’s interior life. An interior life that must necessarily be fictional, however, because Lady Franklin herself would destroy much of her personal correspondence, journals and records before her death. But if anyone is qualified to try to put the pieces back together again, it’s Erika Behrisch Elce, a Professor of English at the Royal Military College of Canada and editor of Lady Jane Franklin’s selected letters, As affecting the fate of my husband, in 2009. And I’m fascinated to consider how this novel must have grown out of that project, and how it felt for an academic to be blurring the lines between fact and fiction as she does here—and what kind of an adventure must that have been!

The prose sparkles in this novel, the plot is riveting even as we already know the ending, but maybe the ending is not the point—it’s the waiting instead. There is so much nuance in these letters, and also plot going on deep below the surface, and Elce also provides a remarkable record of the constraints placed on a Victorian woman, particularly one without a husband, the very opposite of the limitlessness imposed on so many men of the same era.

October 25, 2018

Radiant, Shimmering Light, by Sarah Selecky

Last week, I reread Sarah Selecky’s debut novel, Radiant Shimmering Light, before her panel at the Stratford Writers Festival, which I was moderating. I’d first read the novel back in the winter as a manuscript, and found it strange and fascinating. “Fresh and original, Sarah Selecky’s novel clever satirizes our insta-world but also takes its characters seriously enough to give them an ending that’s moving and transcendent,” so my blurb went. “Deceptively light,” was another blurb, by Lisa Gabriele, and it’s exactly right and what makes Radiant Shimmering Light such a challenging novel. Challenging not in the usual ways—no paragraph breaks or all the characters have names that are adverbs—but instead for how it’s situated in a space between. It’s a satire that takes its characters seriously. This is not Lucky Jim, I mean, absurdity spiralling down into disaster. Which is not to say that book isn’t funny—there is a character called Knigel, for starters. Lifestyle blogs are beautifully skewered by the main character’s friend who runs a blog called “Pure Juliette”, and who guides her followers with cute ways to freshen up their Easter baskets “with things you already have at home! It’s amazing what you can do with silk flowers, a nip of floral tape, and spray glitter.” The novel’s protagonist, Lilian, attempts to self-actualize alongside the personal development gurus she follows online, whose entrepreneurial sensibilities resonate since she runs her own business painting pet auras. It’s all completely ridiculous—someone else makes “consciousness truffles,” whose gluten-free batter is infused with monk chats. Characters attempt mindfulness by meditating on their cell-phone chimes. The perfect set-up for a joke, all of it, but that would be far too easy. And this is where the challenge comes in.

Last week, I reread Sarah Selecky’s debut novel, Radiant Shimmering Light, before her panel at the Stratford Writers Festival, which I was moderating. I’d first read the novel back in the winter as a manuscript, and found it strange and fascinating. “Fresh and original, Sarah Selecky’s novel clever satirizes our insta-world but also takes its characters seriously enough to give them an ending that’s moving and transcendent,” so my blurb went. “Deceptively light,” was another blurb, by Lisa Gabriele, and it’s exactly right and what makes Radiant Shimmering Light such a challenging novel. Challenging not in the usual ways—no paragraph breaks or all the characters have names that are adverbs—but instead for how it’s situated in a space between. It’s a satire that takes its characters seriously. This is not Lucky Jim, I mean, absurdity spiralling down into disaster. Which is not to say that book isn’t funny—there is a character called Knigel, for starters. Lifestyle blogs are beautifully skewered by the main character’s friend who runs a blog called “Pure Juliette”, and who guides her followers with cute ways to freshen up their Easter baskets “with things you already have at home! It’s amazing what you can do with silk flowers, a nip of floral tape, and spray glitter.” The novel’s protagonist, Lilian, attempts to self-actualize alongside the personal development gurus she follows online, whose entrepreneurial sensibilities resonate since she runs her own business painting pet auras. It’s all completely ridiculous—someone else makes “consciousness truffles,” whose gluten-free batter is infused with monk chats. Characters attempt mindfulness by meditating on their cell-phone chimes. The perfect set-up for a joke, all of it, but that would be far too easy. And this is where the challenge comes in.

In our conversation on Saturday, I asked Selecky about this, about the appeal of the narrative space-between realism and satire. Where, as she puts it, the reader is forced to sit in discomfort. But the discomfort is the very point, particularly at a moment when people’s refusal to be uncomfortable has led to dangerous social and political polarization. She talked about how she started with the idea of writing the novel as straightforward satire, but the satire was mean and shallow and she wanted to write something deeper than that. And so Radiant Shimmering Light was born, satire from the inside. She talked about the problematic aspects of online women’s empowerment culture—commodification, cultural appropriation, issues around personal branding—and yet there is something fundamental to the messages as well, messages that do many women a lot of good. “The challenge is to hold both realities at once.”

Considering the ways that books marketed to women are undervalued in a literary sense, it’s not shocking to me that a book about the ways that women are marketed to might not receive the credit it deserves as a sophisticated and multi-faceted novel with literary value. I recall an interview with a Scotiabank Giller jury from a previous year who noted that he’d been able to dismiss certain books out of the gate for being “problematic in their sensibility,” whatever that means, and it’s true that a reader’s first encounter with Lilian Quick might not create a great appreciation for her as a literary character or for the novel as a literary project. Deceptively light, remember? This is a novel about a woman who is silly, and it seems straightforward that such a thing could be so one-dimensional—but this book isn’t. Selecky takes light and lightness, and works it into a novel that is subtly profound. The subtlety not undermining the profoundness, in fact underlining it. The detail is fine, and you have to read closely to see.

I was pleased to see that this year’s Governor General’s Award finalists for fiction includes Sarah Henstra’s The Red Word, a book that left a huge impression on me when I read it, and I read it at the same time I was reading Radiant Shimmering Light. A books whose power is as brutal and difficult as Selecky’s is subtle, but I still see many connections between them. In our Q&A, Henstra talked about her inspiration from a Susan Sontag quote about good fiction existing to “enlarge and complicate—and, therefore, improve—our sympathies. They educate our capacity for moral judgment.” Henstra shares how she had difficulty finding a publisher because her book too is situated in a space-between and didn’t offer easy answers to questions like, “So what’s the takeaway for feminism?” Both are novels situated in discomfort, books that complicate instead of resolve, books that challenge their readers as they offer compelling reading experiences at once. Serious books that don’t wear their seriousness on their jackets/sleeves, and with women at their centres, so sometimes, to some readers, it’s almost like they never happened at all.

October 23, 2018

Something for Everyone, by Lisa Moore

My first Lisa Moore memory is visceral—it was 2005 when I was in graduate school and my husband had recently immigrated and wasn’t eligible to work so we had no money, but then someone gave me a gift certificate for a bookshop, and I bought Alligator, which read like nothing I’d ever read before. So absolutely crackling with life, and the dexterity of the language, and the way she makes every sentence full of twists and turns, which makes work to follow, but oh, the rewards. I loved Alligator; and then I loved February, so much, which inspired one of the best literary essays I’ve ever written: “Women’s literary fiction” is often distinct from literary fiction in general, either because it reads as such (with the squirting nipples, breaking water and placenta on a plate—if a man had written this book it would be surprising), or because it’s come into the world via a woman’s pen and is therefore received differently from literary fiction in general (which is to say, men won’t read it). Sometimes both of these things are true, sometimes one is, and sometimes neither.”

My first Lisa Moore memory is visceral—it was 2005 when I was in graduate school and my husband had recently immigrated and wasn’t eligible to work so we had no money, but then someone gave me a gift certificate for a bookshop, and I bought Alligator, which read like nothing I’d ever read before. So absolutely crackling with life, and the dexterity of the language, and the way she makes every sentence full of twists and turns, which makes work to follow, but oh, the rewards. I loved Alligator; and then I loved February, so much, which inspired one of the best literary essays I’ve ever written: “Women’s literary fiction” is often distinct from literary fiction in general, either because it reads as such (with the squirting nipples, breaking water and placenta on a plate—if a man had written this book it would be surprising), or because it’s come into the world via a woman’s pen and is therefore received differently from literary fiction in general (which is to say, men won’t read it). Sometimes both of these things are true, sometimes one is, and sometimes neither.”

Fittingly, the next time I’d read a Lisa Moore book, I would be in labour, reading the first half of Caught while having contractions in my bathtub—but after the baby was born, unfortunately, I was never able to pick it up again for reasons of association. But I loved Flannery, her YA novel that came out a couple of years ago. Which brings me to her latest, Something for Everyone, which was long listed for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and is one of the best books I’ve read this year. And so yes, you could say I’ve measured out my life in Lisa Moore books indeed.

Something for Everyone is particularly good, however, although I’m not sure it’s really for everyone. First, because short story collections are hard to hold, for readers and reviewers alike—several stories in this collection have the breadth of a novel. Bang for your buck, for sure, but it doesn’t make for easy reading, simple to dip in and out of. These are stories that demand patience and close attention, careful reading. Oh, but the rewards come back tenfold. The very first story, “A Beautiful Flare,” takes place over a couple of minutes in a mall shoe store, the most unfathomable love triangle, but how Moore manages to fathom it, the noise and the chaos and the perilousness of stacked boxes, and “the new heat-sensing Brannock foot measurer…the first innovation to the original design since 1928.” There is something in the way that Moore must see and therefore writes about colour and light, as though through a prism, and the connections she makes, impossible links that fit perfectly, and for just a moment or two, this broken and jumbled up world of ours nearly makes perfect sense. How does she know? About the Brannock foot measurer, and everything, I mean. It must be the most extraordinary way of paying attention, and as a writer it fills me with awe. As a reader it fills me with gratitude.

These are stories born in a time of economic austerity and precarity. Jobs are lost, positions are eliminated, and someone gets swindled in a shady condo deal. Sex workers live in threat of violence, and other workers think about retraining. Old lovers meet in a grocery store entrance in the middle of a blizzard: “The plastic bags flutter in the wind and the doors shut again, leaving us in a vacuum, still as a snow globe.” In “The Viper’s Revenge,” a woman attends a library conference in Orlando two weeks after the Pulse Nightclub massacre, and how her story gets wound up with that of a pool cleaner, in the most tender, perfect, heartbreaking way. It was all very hard to read, and then a story from the perspective of Santa Claus (really) lights up the darkness.

The final story is “Skywalk,” which is just under a third of the book, and is worth the price of admission, really. Taking place over three years in St. John’s with two young people who make a brief connection as a serial rapist stalks the city, and then find each other again later. A dark undercurrent and sense of danger infuses the story with an incredible momentum, and it’s positively gripping, just absolutely exactly what it should be, real as life and masterfully crafted at once.

October 15, 2018

Splitsville, by Howard Akler

Howard Akler packs a lot into a scant 119 pages in Splitsville—a neighbourhood, a city, a legendary municipal battle that’s nearly fifty-year-old. History and geography. The beginning, middle and end of a love affair. Words I didn’t know the meanings of, and which made me pull out my underlining pen instead of rolling my eyes in frustration: aniline; exophthalmic; badinage; ulna; oppugnant.

Howard Akler packs a lot into a scant 119 pages in Splitsville—a neighbourhood, a city, a legendary municipal battle that’s nearly fifty-year-old. History and geography. The beginning, middle and end of a love affair. Words I didn’t know the meanings of, and which made me pull out my underlining pen instead of rolling my eyes in frustration: aniline; exophthalmic; badinage; ulna; oppugnant.

And a mystery: Hal Sachs had run a used bookstore on Spadina Avenue as the debate over the Spadina Expressway was heating up, and he falls in love with Lily Klein, fired from her job teaching civics at Harbord Collegiate for activism. (“The point is: people are really steamed. They’re organizing. That’s the true meaning of democracy. It’s not as simple as majority rules. It’s more about voice, about speaking up and about the city learning to listen to other points of view.”)

On the day before the final decision about the Spadina Expressway is brought down, Hal Sachs disappears. Decades later, his nephew (“Aitch Akler:” this is autofiction of a sort, as I understand it, except it’s not exceptionally annoying, distinguishing this novel in the genre) is expecting his first child, and trying to piece together fact and fiction to understand what happened to his uncle, and what happened to the city whose streets and sidewalks he navigates on a peripatetic journey into the past and into the future at once.

A huge part of my passion for this novel is personal: the characters trace the same sidewalks I walk every day, sidewalks that wouldn’t even exist in the Spadina Expressway plan had not been thwarted—because otherwise my neighbourhood would have been demolished. Every day I walk up Robert Street north of Sussex, a playing field because the houses had been bought up and torn down to make way for the expressway that never arrived. On Saturday, we went out for lunch in Chinatown because Splitsville had made me hungry. I know these streets. But it’s more than that too, this novel fulfils a yearning I’ve had for real and deep conversations about civic engagement at a moment when our democratic rights as Torontonians have just been trounced upon a by spiteful and reckless provincial government. What does it mean to fight for something? Does it matter if you win or lose?

I think you need not be a person who cross Spadina Avenue at least six times daily or be someone whose voting rights have recently been undermined to appreciate Splitsville, however. My passion is only partly personal, and is also about the novel’s attention to language, its literary references, its bookstore setting, the subtlety of its plot and pacing, its absolutely perfect conclusion, and the mystery at its core, questions without answers. I was on Page 93 of the book when I went online and ordered another copy to mail to a friend, which is some kind of endorsement for sure. And now that I’ve read to the end, I want to give a copy to everyone.

October 4, 2018

Notes For the Everlost, by Kate Inglis

As an adult, the very first person I ever knew who was pregnant gave birth to a stillborn baby at full term, which would forever-after colour my understanding of pregnancy and its possibilities, and this understanding would be part of my impulse for creating The M Word many years later, to integrate experiences of loss into the motherhood story. Because a baby isn’t always the outcome of that story, or even a healthy baby—at least not at first. And neither is pregnancy the only path to a person’s understanding of what a mother does and what a mother is. There are so many ways to be a mother, for better or for worse, and in Notes For the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief, Kate Inglis writes about the hardest way, which is to be a mother for a child who is no longer here.

As an adult, the very first person I ever knew who was pregnant gave birth to a stillborn baby at full term, which would forever-after colour my understanding of pregnancy and its possibilities, and this understanding would be part of my impulse for creating The M Word many years later, to integrate experiences of loss into the motherhood story. Because a baby isn’t always the outcome of that story, or even a healthy baby—at least not at first. And neither is pregnancy the only path to a person’s understanding of what a mother does and what a mother is. There are so many ways to be a mother, for better or for worse, and in Notes For the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief, Kate Inglis writes about the hardest way, which is to be a mother for a child who is no longer here.

Now, there are several reasons why one might want to read a book subtitled “a field guide to grief.” Most obviously, if one is grieving—and Inglis has made this a practical book for such a situation, one informed by her experience of running an online forum for bereaved parents. Chapter One is titled, “The Immediate Protocol,” and the first guideline is, “Don’t apologize.” Chapter Three, “What Now,” is about finding one’s way through the first year, and it’s first sentence is, “You’ve got to get up and make breakfast.” There is good advice here, both for the bereft, but also for the people who love those who are grieving. Without being explicit, Inglis has also created a field guide for saying and doing not-terrible things around the grieving—when someone’s baby dies, don’t talk about your dead dog, please. “You will learn to surround yourself with people who understand that occasional sadness is not about them, and who never begin sentences with You should… unless they end with ...come over ’cause I just made soup.”

There’s a lot of generosity here though, toward those clumsy clods who don’t know what do say, or who say the wrong thing, who tell you that your baby’s in a better place now. Inglis writes about people whose miseries pale in comparison to hers—but also how others’ pain might make hers look slight. And what is this hierarchy anyway, and how we all takes turn being above and below. Inglis urges compassion from the grieving—for all those who are really doing their best, even when their best is awful. And there will be days when one can so generous, and other days when such generosity is not attainable, and grief is not a straight line, she writes. There is no perfect metaphor, for how it never goes away, and how it changes. She doesn’t write about “healing,” but instead about “integrating,” an ongoing process.

Another reason to read a book subtitled, “a field guide to grief,” or at least to read this one, is that because Notes for the Everlost is just an extraordinary literary creation—an engrossing and fascinating reading experience, rich with turns of phrase and imagery, as surprising and absorbing as any decent field guide should expect to be. I loved this book for its sentences and its structure, and for the harrowing, devastating story at its core, and the incredible writing, the reflection. A balance of love and anger, moving on and remembrance, holding on and letting go, living and dying, dark and light. As good as A Year of Magical Thinking, but a decade instead, what happens once the magical thinking is over, and even after that. Proof that living through tragedy is possible, even when you think you can’t or won’t. A book about death that—at its heart—is about life, and which dares to ask big questions without pretending to have all the answers.

September 25, 2018

Moon of the Crusted Snow, by Waubgeshig Rice

“‘Yes, apocalypse! What a silly word. I can tell you there’s no word like that in Ojibwe. Well, I never heard a word like that from my elders anyway.”

“‘Yes, apocalypse! What a silly word. I can tell you there’s no word like that in Ojibwe. Well, I never heard a word like that from my elders anyway.”

The first sign that something is wrong is the home satellites stop working, TV screens gone dead. “We might actually have to have a conversation,” Nicole tells her partner Evan when he comes from hunting a moose, and they will pass the evening without their usual entertainment. And by the morning, they’ve lost cell phone service, cell towers a pretty recent arrival in their remote northern community anyway—only built because contractors for the south wanted a signal while they built the hydro dam, and the tower stayed even after they were gone. But there’s no signal now, and soon the landlines will stop working, and the power grid will cease to function. Which raises two big questions: What has happened to the rest of the world? And the more immediately pressing one: how will their community get through the winter?

On the latter point, Evan has some advantages—he can hunt and has been storing food; he’s been reconnecting with the traditions of his Ancestors and this wisdom will guide him; and he and Nicole have built a stable life for their family, which will provide the emotional sustenance necessary to survive a dark and barren winter. But they are challenged when Southerners begin to arrive in the community, fleeing the devastation of towns and cities in the south—one of these men in particular is dangerous. And other members of the community prove to be susceptible to this man’s influence, which begins to divide them at a time when cooperation is essential.

Moon of the Crusted Snow is Waubgeshig Rice’s third book, and it’s gorgeously designed, the story itself quiet and subtle, but fast-paced with heavy overtones. Evan’s reconnection with Anishinaabe traditions as his community is becoming disconnected from the world around them sets up an interesting disjunction, and Rice shows the ways that he has consciously woven these traditions into the life of the family he’s created with Nicole, and how these connections serve them when the situation becomes particularly dire. Evan is also learning the Ojibwe language of his people, and this language is included seamlessly in the text without the use of italics or translation, which offers the text an additional layer of meaning to those who can read Ojibwe—does “zhaagnaash” really mean “helpful friend” I wonder, when used toward Scott, the man who has arrived in their community with big guns and survivalist tendencies?

And yes, there is no Ojibwe word for “apocalypse,” which Evan learns through a conversation with Aileen, an Elder whose teachings he carries with him. Aileen explains to Evan that their world isn’t ending—it already ended long ago when settlers arrived. “When the Zhaagnaash cut down all the trees and fished all the fish and forced us out of there, that’s when our world ended.” But they survived—this is her point. They learned to adapt, and to survive, even as their children were taken and abused in residential schools for generations. “But we always survived,” she tells Evan. “We’re still here. And we’ll still be here, even if the power and the radios don’t come back on, and we never see any white people ever again.”

The ending of this novel is powerful, unexpected, and while deeply satisfying, it’s also ambiguous in a really fascinating way. Moon of the Crusted Snow is a terrific, gripping novel, and one of the highlights of my literary autumn.

September 19, 2018

The Luminous Sea, by Melissa Barbeau

If, like me, you are drawn to Melissa Barbeau’s debut, The Luminous Sea, because of its cover (Ernst Haeckel!) then keep on going because the novel itself is just as gorgeous and rich with wonder. Beginning with Vivienne, a university researcher charged with collecting data on the phosphorescent waters off the coast of Newfoundland, not anticipating her next catch—a sea creature unlike anything anyone’s ever seen before. A little Shape of Water, but there’s no sex in the bathtub, and Vivienne and her supervisor, Colleen, create a tank out of a chest freezer instead. And the creature is a female, or at least Vivienne keeps calling it “she,” even as she’s admonished for the anthropomorphizing. Dynamics in the lab are getting complicated—Colleen’s superior arrives and attempts to take control of the discovery, and in a shocking act of violence (exquisitely rendered in prose like you’ve never seen before) he tries to subdue Vivienne as well. Meanwhile, Colleen is carrying on an affair with a local cafe owner whose wife is wise to it all and spends her time making preserves out of such unlikely things as jellyfish, and Vivienne is only there at all because she’s run away from a broken relationship with her girlfriend in the city. And in the meantime, the creature is not doing well in the tank (“Three days in and scales were coming off in her hand when she touched her, like flakes of opalescent pearls…”), and it might be up to Vivienne to save it. So that this extraordinary novel whose sentences and imagery shimmers and shines is also taut with tension, fast-paced, impossible to put down. But oh, the writing! It’s the writing I keep going on about. The following is my favourite part:

If, like me, you are drawn to Melissa Barbeau’s debut, The Luminous Sea, because of its cover (Ernst Haeckel!) then keep on going because the novel itself is just as gorgeous and rich with wonder. Beginning with Vivienne, a university researcher charged with collecting data on the phosphorescent waters off the coast of Newfoundland, not anticipating her next catch—a sea creature unlike anything anyone’s ever seen before. A little Shape of Water, but there’s no sex in the bathtub, and Vivienne and her supervisor, Colleen, create a tank out of a chest freezer instead. And the creature is a female, or at least Vivienne keeps calling it “she,” even as she’s admonished for the anthropomorphizing. Dynamics in the lab are getting complicated—Colleen’s superior arrives and attempts to take control of the discovery, and in a shocking act of violence (exquisitely rendered in prose like you’ve never seen before) he tries to subdue Vivienne as well. Meanwhile, Colleen is carrying on an affair with a local cafe owner whose wife is wise to it all and spends her time making preserves out of such unlikely things as jellyfish, and Vivienne is only there at all because she’s run away from a broken relationship with her girlfriend in the city. And in the meantime, the creature is not doing well in the tank (“Three days in and scales were coming off in her hand when she touched her, like flakes of opalescent pearls…”), and it might be up to Vivienne to save it. So that this extraordinary novel whose sentences and imagery shimmers and shines is also taut with tension, fast-paced, impossible to put down. But oh, the writing! It’s the writing I keep going on about. The following is my favourite part:

“A long stainless steel table is in the middle of the room. Next to it a second table made from a wooden door laid across two wooden sawhorses and covered with sheets of plastic. Instruments and vials, pincers and thermometers and gloves, measuring tapes and suction-cupped monitors are arranged in near rows on top of it. The doorknob is still attached to the door and makes a small mound underneath the plastic. Vivienne wonders if they have not made some kind of underestimation when considering door security. It seems as if at any minute someone might turn the handle on the supine door, throwing scientific instruments across the room; that someone will will up through the horizontal doorway, like that party trick where someone climbs an imaginary set of steps in the carpet behind the couch.”

Do Not Underestimate Door Security turns out indeed to be one of the novel’s many morals, and maybe (definitely) I’ve got a thing for door imagery anyway, but that paragraph for me is emblematic at how beautifully imagined this novel is, its realities and its many possibilities. There is a generous expansiveness at the heart of the book, doorways onto doorways, but it never grows too strange and mystical and stays controlled, anchored in the physical world, with such attention to accuracy and detail, scientific, like the image on the cover. Melissa Barbeau is an extraordinary writer, and I can’t stop talking about this book.

September 18, 2018

Transcription, by Kate Atkinson

This post is less a book review than “How I Spent My Weekend.” I don’t really know that I’m capable of reading a Kate Atkinson novel critically, or if I’d even want to be. I read them for pure enjoyment, delight, for her narrative tricks, and the way she plays with history, and story. For the little twists that make her books so unforgettable, and how they get lodged in the mind, like how I’m still even thinking of Behind the Scenes at the Museum, even though I read it thirteen years ago.

Since then, Atkinson has waded into detective fiction (igniting my own love affair with the genre) with her Jackson Brodie novels, and then in her two most recent books exploring historical fiction, as ever probing at the limits of what a novel can hold, just how far it can stretch. And that her latest is a spy novel set during during WW2 and also in 1950 is not at all incongruous. Questions of duplicity, reliability, truth and lies, and how History agrees with the factual record are what has fascinated Atkinson from the start of her writing career. I’ve always said that all her books have been mysteries (and maybe all books are in general) and maybe they’ve always been spy novels too.

Transcription is about Juliet Armstrong, something of a cypher, who gets a job with MI5 in 1940 transcribing meetings between a government agent and people who believe they’re reporting state secrets to the Gestapo. As with any book about English fascism during the 1930s/40s (including Jo Walton’s Small Change series) there is a contemporary resonance, although it’s subtle here. In addition to her transcribing, Juliet is enlisted to infiltrate The Right Club, a group of German-sympathizers, taking on an additional identity. And all of these war-time activities come back to haunt her a decade later as she’s working at the BBC (Atkinson has said this part of the story was inspired by Penelope Fitzgerald’s Human Voices) and finds old associates in close proximity again. What do they want from her? What does she have to offer them? Is this just paranoia on her part—there are references to the movie “Gaslight.” How much can the reader trust Juliet at all?

I loved this book—but of course I did. I read it in two days and delighted in that very rare and always exquisite, “I’m reading a Kate Atkinson novel for the first time” feeling. And like all her books, it will bear rereading, even once the twist is known. Because Kate Atkinson is always about more than just tricks, but instead about textual richness, and all the clues you missed that were glaring all along.

September 13, 2018

Late Breaking, KD Miller

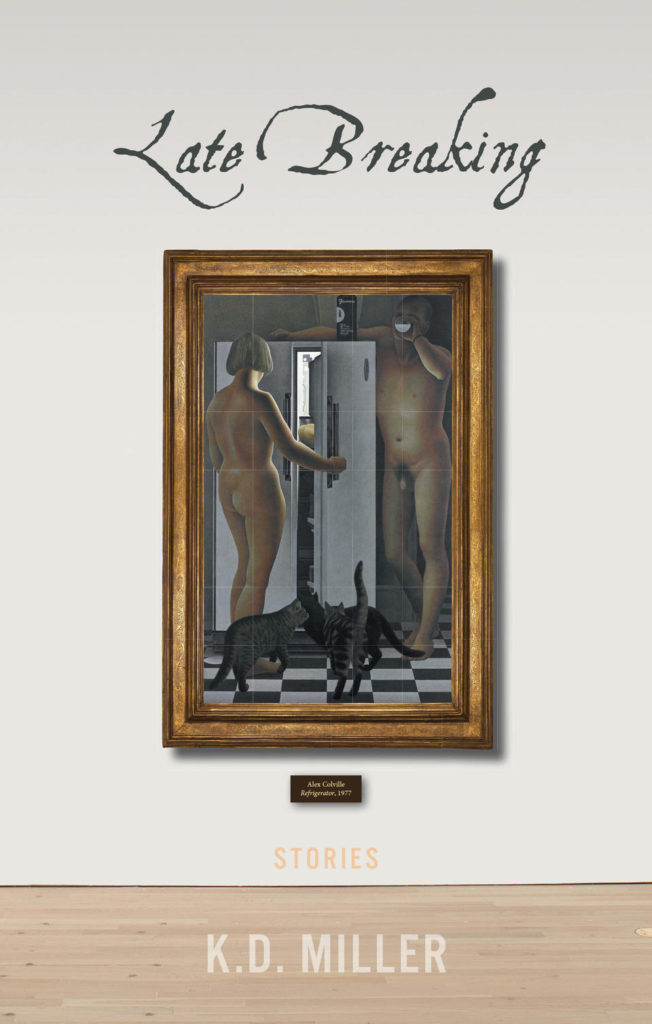

So, if we’re talking about remarkable things, let’s start with the obvious one: the cover. How many other book covers this season feature a naked man drinking milk? I’ll wait. And in the meantime, we can talk about “Refrigerator,” by Alex Colville, which on the advanced copy of K.D. Miller’s Late Breaking that I read was less subtle than it is on the finished version, above. Which meant I felt kind of conspicuous reading it in the dentist’s waiting room the other day, but then I got over it, because the book is so excellent that the penis on the cover quickly ceases to be the point.

And so too does this collection’s conceit, which is that each story is inspired by an Alex Colville painting. Which is not to say that this way of collecting stories into a book is not compelling—absolutely not. It’s an fascinating idea that adds additional texture to Colville’s work, and the stories themselves are similarly absorbing, both ordinary and extraordinary at once, and disturbed by an uncanny strangeness—like the gun on the table, a horse on the train track. Each story is preceded by an image of the painting that inspired it, and the connections between the works are surprising and illuminating both ways.

But this too is eclipsed by something far more central to the text when we talk about the collection: which is that the stories themselves are incredibly good. The first story (inspired by “Kiss With Honda”) is about a widower whose relationship with wife was tainted by a secret she never knew he realized and was never able to explain before he dies, and then he goes to visit her grave, which leads to an act of violence that comes out of nowhere—and suddenly we realize that these stories have teeth, and claws. The second story is about Jill, an older woman whose novel has been shortlisted for an award, and she’s touring with a motley crew of other nominated authors, all the while reflecting on the sex-lives of septuagenarians and the relationship (and heartache) that inspired her work. The third story, “Witness,” takes Colville’s painting “Woman on Ramp” literally—Harriet is the woman on the ramp, and after coming out of the lake and into her cottage, she finds an arm around her neck and something sharp against her back. “Olly Olly Oxen Free” is about the marriage between a woman and her husband, a failed novelist, intersected with story of an older woman in her book club who still carries the pain of a traumatic childhood event. In “Octopus Heart,” a lonely man (who turns out to be the one who broke Jill’s heart in the second story, five years before) feels the first intimate collection of his life with an octopus from the aquarium. In “Higgs Bosun,” a woman (whose son is married to Harriet’s son from a previous story) thinks about the ways she’s tried and failed to hold the world and her family together. In “Lost Lake,” the family from “Olly Olly…” are away at an isolated resort where their daughter seems to be visited by sinister supernatural forces. “Crooked Little House” takes us back to the widower from the first story, and his neighbour (who is the estranged daughter of the octopus man), and their friendship with another man who is trying to make a clean start after twenty-five years in prison. For the murder of a woman who, we realize in the next story, was a friend of Harriet and Jill, all of them meeting one summer long ago—and this story begins with a wonderful scene in a locker-room, older women squeezing into their bathing suits without regard for their naked bodies. “Have we all just given up? Harriet thinks, hanging her suit on a hook in one of the shower stalls and rinsing down. Or is this wisdom?”

These are all rich and absorbing stories on their own, but even richer for how they also inform each other. Eventually I would be making a chart in the back of the book to figure out all the surprising connections, including the final story, about the murdered girl’s mother who was also author of a book about octopuses that preoccupied a character in a previous story. Similar to my friend Rebecca Rosenblum’s work, K.D. Miller’s fiction seems to conjure whole worlds, with characters who seem to walk off the page and who—one has no doubt—continues in their adventures even when their stories are finished. We get glimpses of these people, but they’re like the tip of an iceberg and there’s so much more going on beneath the surface. Which is something you could say about the people in Colville’s paintings too, and about each of these stories themselves, compelling and disturbing, and impossible to look away from, creating the most terrific momentum.

August 30, 2018

Women Talking, by Miriam Toews

“No Ernie, says Agata, there’s no plot, we’re only women talking.”

Women Talking, the latest novel by Miriam Toews, is not an easy read. Not easy because of the places it takes its readers to—the women talking in Women Talking are women from a Mennonite community in Bolivia, women whose husbands/brothers/sons have been accused to raping the women while they were sleeping, incidents based on real events, so-called “ghost rapes,” and it’s how women respond to and try to move on from this trauma that raised important questions for Toews as she considered writing this book, more than the fact of the violence itself. Because violence is ubiquitous. As Toews said in conversation with Rachel Giese when I went to see her last week, she can imagine what a rape is like. But what happens after—how do you imagine a way through that? And then she said something else, an echo of line in the novel which I read a few days later: “We are all victims, says Mariche./ True, Salome says, but our responses are varied and one is not more or less appropriate than the other.”

This line reminded me of Jia Tolentino’s article in The New Yorker on The Women’s March in 2017, and the way that so many were quick to jump on organizational conflicts and disagreements as a way to dismiss the movement altogether. Scoffing is often what happens when we hear about women talking—it’s either idle gossip, or else a petty scrap. A catfight. Women talking—it’s on the background, unless the voices are shrill. Or when they’re allowed to be a chorus. But in her novel, Toews dares to make women talking everything. The “there’s no plot” line is a funny meta-joke. But this is difficult too, on a practical level. To follow along with the conversations, to discern who these people speaking are as we’re just beginning to know them as characters. And Toews complicates the work further by refusing to make any of her characters just one thing—these are women who are difficult, who argue with each other out of spite, who contradict themselves and turn their own arguments inside-out, because this is what thinking is. For the first half of the novel, I confess that I was a little bit lost, finding the narrative hard to follow, and not remotely sure how the whole thing would come together.

But then mid-way through, something happened—it was like the walls started closing in on the threat to these women in the hayloft talking, these women who were daring to defy their husbands, brothers, sons. To explore the three options available to them: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave, but then the men who’ve gone to the city to post bail for the others could return at any time. And suddenly this novel without a plot takes on the most furious momentum and becomes unputdownable. In this novel in which nothing’s happened yet, something is going to have to give—but what?

The women talking in the novel are people who’ve never learned to read or write, who cannot read a map, and know nothing about the world beyond the boundaries of their communities. (I read this book right after Claudia Dey’s Heartbreaker, which is such a completely different novel in spirit, but there’s a kinship between them.) As the women in the novel are illiterate, writing down the minutes of their meeting is tasked to August Epp, an estranged member of the community who has returned after years away to serve as a school teacher (which is basically to be a failed farmer, and shameful occupation for a man). And August’s own complicated story, and his love for Ona, one of the women whose words he’s recording, becomes a foundation for the novel, as it would be, although just why or how does not become apparent until the conclusion, which only adds to its devastating and beautiful ambiguity.