August 27, 2019

The Need, by Helen Phillips

“She and David had a running joke about how they both feared their kids at night the same way that, as children, they’d feared monsters under the bed. Beasts that would rise up from the side of your bed, seize you with sharp nails and demand things of you.”

I’ve been hearing things in the night for my entire life, the sound of footsteps, or maybe the house is just settling, or the sound of the wind outside. What was that? But it’s only since I’ve become a parent that I actually see things, that I awake from sleep with the uncanny feeling of someone standing over me, and I open my eyes and there they are, my worst fears confirmed. (And the fear, I mean, is in addition to the practical matters, that these nighttime visits are generally a harbinger of the fact that I’ll have to clean up puke.)

In her novel, The Need, Helen Phillips zeroes right on this kind of anxiety (albeit regarding an even more sinister nighttime interloper) in the book’s first three sentences: “She crouched in front of the mirror in the dark, clinging to them. The baby in her right arm, the child in her left./ There were footsteps in the other room…”

Molly’s husband, a musician, is away on tour, and she’s just relieved the babysitter. She’s the primary breadwinner in the family, a paleobotonist who works at a site that’s turning up baffling specimens: plant fossils that don’t seem to related to any other living thing on earth, an Coca Cola bottle whose logo slants backward, a Bible that addresses God as “her” and “she.”

Something is askew, but also everything is askew, because Molly has a baby and a toddler, which means she hasn’t had a proper night’s sleep in years, and her hours are consumed by her children’s near insatiable needs and demands upon her. So there is something metaphorical about the otherworldliness Molly is experiencing at work, and we’re to doubt her perceptions—are there footsteps at all?

But the footsteps are real, and the stranger in the other room wearing a deer mask has a bizarre awareness of Molly’s family’s life and their rhythms—and the reality behind this situation turns out to be nothing like what you’ve expected, and it continues to be questionable how much the reader can understand this as “reality” at all.

This is a novel in which everything is true and possible, and nothing is; where a child’s birth and existence contains the possibility of their death; where doubleness is a solution and a nightmare; where the cessation of what seems unbearable is unsurvivable; and where the figurative and literal do battle, as do the fantastic and realistic; and ambivalence has its every nook, cranny and sub-basement explored.

This novel starts off terrifying, and the way Phillips sustains that suspense (moving back and forth between two timelines, plot, twists and pacing) is astoundingly well done. Though I will admit that by the time my biggest questions had been answered (which only invited plenty more questions still, of course) I was less enveloped by the plot—though probably for the best, if we’re thinking about my blood pressure.

All this with a novel that articulates the minutiae of daily life with children like nothing I’ve ever read before, a twisted and brilliant version of Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work.

And then the ending—so dark and banal at once. So subtle that you might even miss it, but the subtlety—of the violence, the brutality, that you could miss it—is the point. The Need is a fast read, but it’s haunting.

August 2, 2019

Mrs. Everything, by Jennifer Weiner

I had an oddly optimistic revelation about the world the other day—odd, because I haven’t had an optimistic revelation about the world for at least four years—which was that when people look back on the literature published in the second half of this decade, they’re going to be thinking, “Good gracious, the Patriarchy (RIP) on its last legs must have been quaking in its ugly boots.”

Because the books are so feminist, and furious, confronting racism and violence against women. Fiction and nonfiction, commercial and literary—I promise I haven’t been even deliberately seeking them out. But almost every book I’ve picked up this year, and certainly every one that I have loved, has been staring the patriarchy in the face and having none of it. Refusing to submit, to be polite, to keep things uncomplicated, to tolerate the status quo.

And in 25 years—after the current US president has been found dead on a toilet, the stupid red hats have disintegrated (cheap production will do that), and a few remaining rat-men have built an all-male colony out in the ocean on an island constructed from millions of copies of 12 Rules For Life (I would LOVE to know the number of people who bought that book versus number of people who finished it; is that why it keeps selling? Because the reader hopes a different copy might prove worthy of their attention?)—these books will be what remains of this time, the culture we made.

It’s sort of like the illusion I once bought as a young person that the 1960s was only groovy and folk songs, instead of political assassinations, endless war, and racial violence. You know the expression, “You had to be there.” In this case, it’s kind of the opposite. It’s even better if you weren’t.

And this is the gist of Jennifer Weiner’s latest novel Mrs. Everything, her thirteenth novel and her tour de force, a novel that reminded me of recent work by Meg Wolitzer and Lauren Groff. My one criticism that it started out unsteady, the story of a family in the 1950s whose American Dream is coming true, a mother and father and two daughters who’ve just moved into red brick house in Detroit. The characters are a bit stock at this point, the good girl and the bad girl, their disapproving mother, some manufactured drama…but then the novel starts going and it never stops.

What I love best about this novel is what I love best about any narrative that features more than one woman (which is the only kind of narrative I love at all, to be honest). That the women in the book are not foils, that their characters and narrative development is sufficiently complicated, and that their relationship is as much supportive as it is fraught. And such is the way with Jo and Bethie Kauffman, the two sisters who grow up in that house in Detroit. One is posed to be the good girl and the other is the problem, and then fate intervenes and neither one ends up on the trajectory that she, the reader, or anyone else imagines for her. Jo will become a suburban housewife, Bethie the counterculture rebel, but neither archetype is the whole story, and the whole story is mostly that there is no right way to be a woman. We live in a society that’s going to mess with each and every one of us.

The novel takes the sisters from the 1950s through to the present day, and beyond, and its fabulous momentum builds as it goes. The sisters come together, are pulled apart, face heartbreak and trauma, keep going, keep learning and growing wiser all the time. This is a story of women, and civil rights, and the rise of LGBTQ rights as well.

The constants? Weight. It’s not a theme of the book, but it’s always in the background, as its always in the background (maybe not so far back) of the lives of almost every women I know. Feeling fat when you’re not, and then actually being fat—is it not remarkable that women are able to feel badly about themselves no matter what their size? It’s a fascinating narrative strand in the book. As is the idea of mothers wanting something different and better for their daughters than what they themselves have had to go through, but the thing about daughters (who are women, who are people) is that they don’t always want to dream the dreams their parents dream for them, and they have to learn from their own mistakes, and also none of us want to entirely believe that we’ll be subject to the same rules our mothers were. We’ll do it different, this time, and we do, but some things stay the same, as Mrs. Everything serves to underline.

As Michele Landsberg explains in her book Writing the Revolution: “Because our history is constantly overwritten and blanked out…., we are always reinventing the wheel when we fight for equality.”

But I would like to believe there is something different about the current moment we’re in, when women are finally courageous enough to call out discrimination, abuse and violence, to finally call things by their names. Because in not being able to do so before, were we blanking out our own history, our own experiences? Doing the work of the Patriarchy for it, but no longer. I hope.

Mrs. Everything misses absolutely nothing.

July 19, 2019

Your Life is Mine, by Nathan Ripley

In two days, I tore through Your Life is Mine, Nathan Ripley’s second novel, (his debut was Find You in the Dark), a book that got richer and deeper as its complex plot progressed. And isn’t that rare? A thriller whose meaning intensifies as the reader gets closer to the resolution?

I loved it.

The protagonist is Blanche Potter, a documentary filmmaker who’s just beginning to enjoy some success with a true crime feature, but she just can’t escape the notorious true crime in her own history, no matter than it was years before and she’s changed her name, and no one (except her best friend Jaya) knows who Blanche really is. That she’s actually the daughter of cult leader Chuck Varner who died after a killing spree that Blanche was witness to as a young child. And Blanche would not be surprised if her father still has followers out in the world intent on carrying on his violent mission, because she knows from experience—she herself spent much of her life under by his spell.

Which is why the news of her mother’s murder delivers Blanche some relief at first—one less tie to Chuck Varner, because Blanche’s mother had never shed her devotion to the man or his message, and getting over having two such messed up parents has been the goal of Blanche’s adult life. She even appears to be succeeding at it…except the news of her mother’s death has been delivered via an aspiring writer who knows too much and wants Blanche to share her story. And he also reports that Blanche’s mother’s murder was a random act, but Blanche knows there’s never been anything random about her tortured family life.

And so she returns to the scene of the crime, which is also the scene of her childhood, to find out who really killed her mother, and if the killer is likely to strike again. But is the whole thing a trap? It’s hard to tell who can be trusted, least of all Blanche herself who has buried years of trauma which is now returning to the surface, threatening to upset the careful arrangement of her present, and she could even end up dead.

The narrative moves between Blanche’s perspective, excerpts from a true crime book about her father’s legacy, and other secondary characters whose roles in the story take a while to become clear. There’s also a dodgy police officer, the sketchy guy who runs the trailer park where Blanche’s mother lived, and the aspiring writer—what are their connections to Chuck Varner? Is Blanche just being paranoid? And what is the most terrible part of her story, the part she has not yet told to anyone?

The novel begins with a broad canvas, but the story gets narrower and narrower as it gets closer to the climax, and doesn’t rely on all the usual tropes for this to work. One of my favourite characters in the book was the utterly effective police officer who comes equipped with a dose of humility, and actually listens to the protagonist—have we ever seen him in fiction before? And underlying the impressively crafted plots are all kinds of ideas about race and class, and gun control, cultism, misogyny and more. The story never stops being interesting, even as the pages are flying along.

July 3, 2019

Molly of the Mall, by Heidi L.M. Jacobs

I am positively besotted by Heidi L.M. Jacobs’ debut novel, Molly of the Mall, which I kind of suspect was written just for me, a 1990s coming-of-age tale of a young woman who aspires to be an authoress and works at a mall. But not just any mall—the West Edmonton Mall, with its peacocks and water park, as far from Jane Austen as a mall can possibly be. A novel that is a teeny bit Bridget Jones’ Diary, if Bridget happened to work at a shoe store, and a whole lot of a Caitlin Moran-esque tale of how to build a girl, except instead of coming from a working class family in Wolverhampton, Molly’s the youngest daughter of a pair of academics, which can similarly render a person a misfit.

I loved this novel.

It takes place over the course of a year as Molly spends a summer working Le Petit Chou Shoe Shop (big on up-selling polish and sprays) and then going back to school for the third year of her English studies, feeling out of her depth in academia, aspiring to write a Jane Austenesque novel set on the Canadian prairies, and (naturally) wondering about love. There are several contenders for her male romantic lead, including a childhood friend who’s in her English class, her sister’s old boyfriend, and a mysterious man at the mall who she meets in the Penguin Classics section of the bookstore.

This is not a novel that anybody would ever call taut—but let’s not hold that against it. Instead of taut, this novel is a trove of delights, including a Jane Austen-inspired mix tape (side 2 is Mr. Darcy’s, and includes Chicago’s “Hard to Say I’m Sorry”); fragments of Molly’s ridiculous school assignments; passionate thoughts on Oasis and the Gallagher brothers (and an amazing passage on the first time she hears “Wonder Wall”; a fabulous plot thread on Molly’s determination to reclaim the works of James McIntyre, Canada’s cheese poet; and the part when her manager discovers she’s plotting her novel on a boring shift at the shoe store, instead of building polish displays, and she concocts a falsehood about writing a fan letter to Roy Orbison (“After an awkward silence, Tim looked at me and said, ‘You know he’s dead, right?’ I looked at the floor and nodded. I whispered, ‘It’s still too soon. I don’t want to talk about it.”)

If none of this sounds remotely appealing, then I am not even going to try to convince you. Molly of the Mall may not be for everyone. But if you came of age in the 1990s, worked in a shopping mall, longed for a literary life, ever felt a bit weird about your dad’s devotion to Robbie Burns, dreamed of a romance that was swoon-worthy, felt confused in university English classes, and let 19th century novels play perhaps too great a role in informing your perspective on…everything—then you will not be sorry. It’s also a really beautiful love letter to Edmonton.

Read this book.

June 26, 2019

Big Sky and The Last Resort

To start with, the Jackson Brodie novels were not my favourite Kate Atkinson, but of course I’d read anything by Kate Atkinson. And while indeed these books were my gateway to detective fiction—it seems unbelievable now that I ever needed one—I always preferred my Kate Atkinson more literary. Reading Behind the Scenes at the Museum was one of the most important literary experiences of my life.

But I also know that for many readers, the Jackson Brodie novels were a gateway to Kate Atkinson altogether, before Life After Life and God in Ruins, which were each a brand new level of success in an already remarkable career. And so there has been considerable excitement around Big Sky, Atkinson’s first Jackson Brodie novel in years. But I was not expecting to fall as hard for this novel as I did.

And I did, oh did I ever, carrying hardback book in my bag with glee and pulling it out at every opportunity. The kind of book that makes you only want to be reading, conjuring an incredibly intricate fictional world that’s just meta enough that you know it’s Kate Atkinson, and with real world ties that make Big Sky a novel that’s important as well as delicious.

In this book, Jackson Brodie stumbles backward into a human trafficking ring that had its origins in pedophile rings made up on 1970s’ high profile entertainers, which is not the stuff of fiction, if you’ve been reading the UK press in the last five years. The links between then and now are part of what the story is out to discover, and Atkinson does fascinating things with plot and time to tie the pieces together, and she is a writer so firmly in command of her story and all its threads, almost as though the threads were reins creating the novel’s momentum, making the story go go go.

Underlining everything in this book—the humour, the pleasure, the characters, Jackson’s ex-wife’s voice that’s now stuck in his head—there is rage, rage at the use and abuse and exploitation of vulnerable girls and women by hideous men, and this is a fiercely and furiously feminist novel that’s intent on justice, which isn’t always on the side of law, because the law has protected too many of these hideous men for too long, and Jackson Brodie is having none of it.

—Although it’s not actually Jackson who breaks the case, as he continues stumbling backward—as is often the case, it’s the women who get things done, not to mention a washed-up drag queen, an emotionally intelligent teen-age boy, and the lyrics to “Let It Go.”

“Let it Go” does not factor in The Last Resort, the latest (and bestselling!) novel by my friend Marissa Stapley, but it’s a novel that fits neatly with Big Sky, which I realized this morning as I was reading the latter at its climax. Both novels are about girls and women who’ve been abused and manipulated by hideous men who know just how to wield their power, until things finally reach a breaking point. The Last Resort is set at a luxury resort in Mexico run by a pair of married celebrity marriage counsellors whose own repressed secrets are beginning to rise to the surface, just as a deadly storm is rolling in, and one thought crystallizes like an icy blast: “They’re never going back (to the patriarchy), the past is in the past.”

Burn it down, blow it up, push the bastard off a cliff./ The women are furious, and they’re not taking any more shit.

Okay, I made that part up, with a little inspiration from Elsa, but I reread The Last Resort last week and found it even more compelling than I did upon my first read, appreciating Stapley’s (I refer to all women authors by their surnames in reviews as a feminist statement, even when those authors are my friends) willingness to complicate, to ask questions about women’s complicity in the abuse of other women, to have her readers sit uncomfortably in that space, and to implicate patriarchal institutions—the church, marriage—in such an unabashedly feminist manner.

Packaging all that up inside a plot that zips along and makes for such a gripping read—what more from a book could you ask for?

June 5, 2019

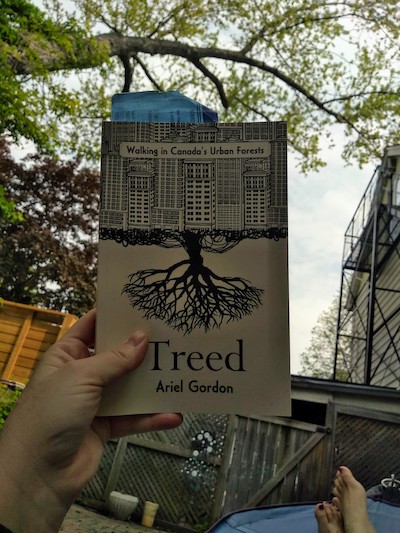

Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests, by Ariel Gordon

Ariel Gordon’s brand new essay collection Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forest, was just the book I needed last weekend, a weekend we headed into amidst news headlines of rising water and forest fires, which I was finding positively dispiriting. And yes, of course, it is supposed to be dispiriting, but I also just can’t live like that, so certain in my despair. I need to still love the world, and find wonder here, and it’s a kind of compulsion, which is what Treed is all about as it makes a kind of sense of the messiness—of hybrid spaces, our history of colonialism, of contradictions, tension and balance, and the absolute insistence of wild things. The very fact of an urban forest.

“But this is a multi-use space. It is a public space. Which means people bring to the forest what they have: Dogs. Children. Inappropriate nudity.”

Treed is also a book about mushrooms, which if you’ve known Gordon online for any length of time is unsurprising, and about the way that mushrooms became her gateway to Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Forest as she began to explore this space which was overwhelming in its immensity, but noticing mushrooms was about detail. And the book’s third essay is a diary of these explorations as Gordon moves through the seasons of the year and of her life, and it acquaints us with the subject, our intrepid narrator, and the space and trees that come to fascinate her.

There are challenges and complexities: balancing urban trees with development, fighting diseases and pests, that trees have a natural lifespan at all, invasive species, monocultures, balancing the needs of people with the trees they live amongst, and Pokemon Go vs. proper exploring (and her cat), and Gordon shows that these complexities are more complicated than she properly understands, a perfect balance impossible, the tension inherent. The challenge of being a living thing on the planet.

I loved this book, which was also about balancing motherhood and writing, the family and the self, solitude and community, city life and the inexorable fact of nature, abject despair indeed and the wonder that is everywhere, if you care to look—starting with the mushrooms.

May 13, 2019

Spring, by Ali Smith

I wasn’t so much addicted to the spectacle as to the ongoing certainty that the next click, the next link, would bring clarity. I felt like if I watched everything, if I read every last conspiracy theory and threaded tweet, the reward would be illumination. I would finally be able to understand not just what was happening but what it meant and what consequences it would have. But there was never a definitive conclusion. I’d taken up residence in a hothouse for paranoia, a factory manufacturing speculation and mistrust.

Olivia Laing, “I was hooked and my drug was Twitter”

I don’t always love Ali Smith’s work (How to be Both did not do it for me) but I cannot overstate what the books in her seasonal quartet have meant to me since the world descended into Worst Possible Timeline, which I date to June 16, 2016, the day that British MP Jo Cox was murdered outside her constituency office by a man who shouted, “Britain First.”

What is going on here, I remember asking myself in horror (except with more expletives) and then again a week later when the Brexit verdict was delivered, and six months after that when Hillary Clinton did not become the first woman President of the United States, and then basically about every ten minutes ever since then. Clinging to Twitter, as Olivia Laing describes in her essay, to make some kind of sense out of this real time nightmare—but then again if there was any sense to be made of it, Twitter would not deliver, because it’s in their interest to keep me refreshing my timeline, to have me yearning for clarity and illumination but never actually delivering.

But then in the Spring on 2017, Autumn arrived, the first book in Ali Smith quartet, set just six months before I was reading it, which is a remarkable turnaround in the world of publishing. And the books in this series are the closest I’ve ever come to the clarity and illumination that Laing is seeking in her essay, the clarity and illumination that I’ve been craving ever since I started to realize that the world is a vastly different place than I’d supposed it was. Even though it’s not so clear or altogether illuminating, but still—that Smith is fashioning art and story out of these times that we’re living in. I get comfort from that. A lazy kind of comfort, possibly, and her novel Winter—published in January 2018 (I walked through a blizzard to get it)—alludes to this. That turning these events into literature puts then at a distance that makes me feel better, and maybe I don’t deserve to. Look, here’s art. These things are cyclic. It will be fine.

It’s not fine, and I know it’s not fine, but I am still roused at Smith’s ability to articulate our situation in her novels. Spring came out this month and begins with four pages of run-on text that appears to be cribbed from Twitter. “We need the dark web algorithms social media. We need to say we’re doing it for free speech.” And then the story begins with a screenwriter who is mourning the death of an old friend who was briefly his lover and who was also his mentor. (What is going on here?) He’s on a train platform in the north of Scotland, and he’s mostly lost in nostalgia, and the train doesn’t come.

In the next section, more disturbing zeitgeist (“We want you to know how much your face means to us. We want your face and the faces of everyone you photograph and the faces of all your friends and the faces of the people they photograph recorded online for our fun data archive and research…”) and then a young woman called Brittany Hall who works as a guard in a detention facility for asylum seekers and/or illegal immigrants—but something strange is afoot. A young girl who managed to get through the barricades, past the guards, inside locked doors and into an office where she convinced the powers that be to have the facility professionally cleaned. Which is to say that it no longer smells like shit in this place where actual people live anymore, even though Brittany Hall has forgotten these are people, because you have to forget, or else how can you bear it. And Brittany Hall is going to end up with this girl on a train to the north of Scotland where they’re going to cross paths with the screenwriter, and like the other two books in the series, this is a novel about art, and the nature or art, and the purpose of art. About hope (springs eternal), because what is art but hope embodied after all.

April 29, 2019

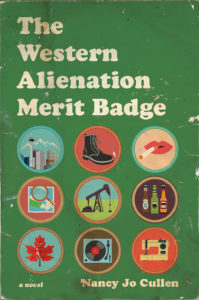

The Western Alienation Merit Badge, by Nancy Jo Cullen

Nancy Jo Cullen’s debut novel The Western Alienation Merit Badge (which follows her award-winning story collection Canary) begins billions of years ago: “After the inland sea dried up and its beaches turned to sandstone and the plant life turned to coal and gas…” Although by the end of the sentence, we’ve arrived in the 1970s, a small girl emerging from the bushes with her cap-gun loaded, a copy of The Guide Handbook tucked into her waistband. But we will not discover just who the girl is or where she’s come from exactly for about 150 pages or so. And the point is this—that while history stretches long here, it’s never out of sight, and everybody’s looking backward, behind them, time unfolding like a peacock’s tail.

Although there is nothing as extravagant as that in the novel’s first section, which takes place in Calgary, Alberta in the autumn of 1982. Which is why it’s particular hard for Frances to be home again, her European adventure cut short because her stepmother had died and her family needed her. Leaving behind her girlfriend and a certain amount of carefreeness in Portugal to come back to Calgary, which has just lapsed into recession. Her widowed father is taciturn and has taken up needlework as a way to connect with his wife, and Frances’s furious sister has problems of her own. So when Frances reconnects with a woman from her past, and her (Catholic) family begins to understand that she’s a lesbian, things go over just about as well as you might expect.

The Western Alienation Merit Badge was a pleasure to read, and in terms of craft is remarkable for two particular features. The first is for its points of view, which move between characters providing vastly different perspectives on the same situation, and while the few times this happened mid-chapter it was a bit jarring, the result of this approach is a complex and multi-layered narrative that is really effective in particular because of how Cullen avoids cliches and sentimentality in creating her characters and their dynamic. There’s no wicked stepmother trope here, as Frances had really loved her stepmother, whose arrival in the household had made their broken unit into a family—and they’re all lost without her. Her father’s grieving process, taking up quilting and knitting and trying to channel his wife through her sewing machine, was unlike anything I’ve ever read in fiction before, and such an incredible way to add an additional dimension to a working class guy, the kind we’ve all read about in fiction before. But will his sensitive side extend to understanding the life of his lesbian daughter?

The other remarkable feature of the novel’s construction is that after a short second section set in 2016, the novel takes us back in time. Not quite as far back as when the inland sea dried up, but instead to 1974, before Frances’s stepmother came into the picture, and here the reader is provided with the solution to much of the puzzle regarding the kind of people who the members of this family would become. Because Alberta is the kind of place, the novel is suggesting, where the answers to questions still lie in the past, which is why this novel set in a recession-era Calgary circa 1983 seems so absolutely timely in 2019, in particular as the province has dominated national headlines lately with their recent election.

If you’re not from Alberta and want to understand why Alberta is the way it is, and the way many people who live there feel about themselves in relation to the rest of Canada, this novel is a good place to start.

April 24, 2019

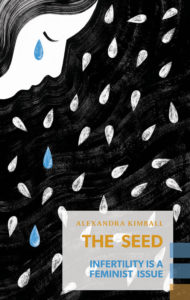

The Myriad Nature of Maternal Grief

Everything I know about infertility, I’ve come to understand through the analogy of abortion, which is not the opposite of infertility—though some people might have you imagine so. For your information, adoption and miscarriage are not the opposite of abortion either, as the many people who’ve had both abortions and miscarriages can definitely attest, and those women who’ve experienced adoption too. (And pay attention here, to the challenge of going beyond a single story in women’s experiences—a theme. To an insistence in our rhetoric on either/or, and maybe neither if you’re lucky, but never both.)

While I’ve not experienced infertility, I have had an abortion, which means that I’ve spent a lot of the last seventeen years thinking about reproductive choice (which delivered me the rest of my life, after all, so I spend a lot of time saying thank you). And in this thinking it occurred to me that such notions of choice must necessarily include women who want to be pregnant but aren’t, women I feel solidarity with because both experiences (wanting to be pregnant when you’re not and not wanting to be pregnant when you are) have feelings of grief and such abject despair at their core. And similarly do abortion and infertility attract the wrath of patriarchal forces, because there is nothing our society likes less than a woman who exercises agency over her destiny, who refuses to be a passive vessel.

(An additional commonality I’d never considered until reading Alexandra Kimball’s book is that abhorring abortion and dismissing the trauma of infertility both require diminishing the physical labour required to be pregnant and also that to become pregnant through reproductive technology. Abortion and infertility treatments are both considered, by those who don’t know any better, as a matter of simple “convenience,” equivocating women’s labour with, just say, a breakfast sandwich from Starbucks.)

And so Alexandra Kimball’s The Seed: Infertility is a Feminist Issue was always going to one of the books I’ve most been looking forward to this spring. (The first time I read Kimball’s work was a 2015 essay on miscarriage, which was also about her abortion, and I am always interested when abortion/miscarriage/infertility are part of the same conversation; and note: they were also all part of the conversation in the anthology I edited in 2014, The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood).

But I will admit that while I was looking forward to The Seed, its thesis (that feminism has failed infertile women) made me uncomfortable—and certainly it’s even supposed to, and it’s provocative. But what I mean is that I didn’t start reading the book completely on board, and I felt its central premise would possibly be a bit overstated. (This is kind of like when you’re white, and a racialized person tells you about their experience of racism, and you suppose they’re just being a bit sensitive.)

But it was by about page 50 and her analysis of The Handmaid’s Tale and infertility in pop culture (after the chapter on infertile women as monstrous in myth and folklore, beginning with a Babylonian epic from 18th century BC, right up to witchcraft trials just a couple of hundred years ago) that Kimball had me convinced that she was not just being sensitive. After discussing pop culture infertility in films like Fatal Attraction and The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (infertile women literally destroying the everywoman’s life) she turns to The Handmaid’s Tale, and concludes that while it is “unequivocally, a feminist text…in its world, female barrenness is not only…threatening…disgusting… it is outright oppressive, a necessary engine for patriarchy itself.”

Kimball’s analysis from here is about the tension within feminism toward motherhood in general: “an idea of motherhood as conscription into patriarchy remained central to feminist theory and action.” And how feminism’s emphasis on CONTROL in terms of reproduction left little space for those women whose experiences were beyond their control—she quotes Linda Layne on the monumental Our Bodies, Ourselves, which included miscarriage and infertility in a separate (and unillustrated) chapter at end of the book.

And who exactly gets to be in control of their reproductive lives was quite specific from the start in feminist circles—racism and classism have always played a role in this. So that even now, the experiences of racialized, queer and poor people are alienated from conversations about fertility, which itself is alienated from conversations within feminism anyway. Kimball shows numerous examples of people in general and feminists in particular being much more concerned with and disturbed by ideas about people resolving their infertility than the problem of infertility itself.

And why is it so easy for our rhetoric to remain so unconcerned about the experience of the infertile woman? “They ignore the grief,” writes Kimball, who notes that she has never felt as objectified as she did when she was infertile. “It’s difficult to see [an infertile woman] as anything other than a curiosity of capitalism, akin to people who undergo cosmetic surgery.” She writes about “the existential clusterfuck of this trauma,” how the tragedy of infertility is that resolution always seems just close enough at hand to be worth pursuing. “It’s less of a biological impulse than a narrative one, a need for coherence and sense.”

And here, Kimball begins to see the possibilities of sisterhood, of solidarity, for she finds it with a friend who a trans woman whose own experiences have been very different but who understands the extent of Kimball’s grief in a way that few other people do. (Kimball also points out that Trans-Exclusionary-Radical-Feminists find women pursuing fertility as challenging to their politics as they do trans women.) She further identifies with the the artworks of Catherine Opie and Frieda Kahlo, how they portray bodily labour and grief. “I looked at Opie’s portrait series and Kahlo’s miscarriage works frequently when I was struggling, not so much because they mirrored my own experience or made me feel less lonely, but because I was heartened by what I felt was the complexity of their stories… They demonstrate the myriad nature of maternal grief.”

That myriad nature is explored in the essay anthology Through, Not Around: Stories of Infertility and Pregnancy Loss, edited by Allison McDonald Ace, Ariel Ng Bourbonnais and Caroline Starr, a work that challenges “the single narrative” that Kimball complicates and writes against in her cultural analysis. In Through, Not Around, the political is made personal again with 22 stories of infertility, miscarriage and stillbirth, mostly by women, but with a handful by men. Each writer is telling a story that is far from uncommon, but which was until recently taboo (and even remains so in many cultures). As Kimball writes, society is made uncomfortable by evidence of the effort and labour of motherhood, would prefer it to remain hidden so we can continue to believe it is natural, essential.

My only critique of this collection is the lack of contributor bios, because it would be interesting to see what a range of backgrounds these writers are coming from. (Although I try to think of reasons why contributor bios might be avoided here, and I can think of some answers. What happens when we let the stories speak for themselves?) My sense is that these writers come from a fairly broad spectrum of experience (although, for reasons Kimball has illuminated, racialized, queer and poor women are in the minority here, as they are in conversations about fertility in general) and that most of them are not professional writers. (The anthology was born of the online community The 16 Percent.) And so I was impressed by how excellently written most of these essays were, how they made stories out of experiences that defy the conventions of narrative at every turn. (There is a reason you rarely read a novel where someone ends up having five miscarriages.)

The grief that Kimball writes about is evident in these essays, which are stories of strength and resilience under sometimes unrelenting pressure. The point indeed is getting through, which requires action instead of passiveness. But also questions of when to try a different path forward, when to stop, and all the surprising diversions that happen along the way. Women’s lives, we read in these essays, are fraught and brutal and hard and knit with tragedy, but are also unfailingly interesting.

There are so many ways to be a woman, and to become a mother, or to be infertile, even. I’m grateful to both these books for complicating the narrative in the very best way.

April 4, 2019

A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, by Alicia Elliott

One of the first essay collections I ever fell in love with back when I was first falling in love with the essay was Pathologies, by Susan Olding, who was later kind enough to write a short piece at 49thShelf about the essay form. Olding wrote, “In an unstable world, we want to know what we’re getting, and with an essay, we can never be sure. Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go. Places we may not want to go. We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave. That’s the risk we take when we pick up an essay.”

It might be the risk, but it’s also the reason, as demonstrated by Alicia Elliott’s remarkable and now-bestselling debut, A Mind Spread Out On The Ground. A collection of essays that examine stories and ideas from all angles, not one side, or even (more importantly in this age of polarization) both sides, but instead acknowledge a myriad of viewpoints, or points of consideration. These are essays that resist certainty, neat conclusions, simple morals. Instead: there is multiplicity, complication, tension, and this is what makes the book so fascinating. “Sontag, in Snapshots” begins with self image and photography; and then photography and colonialism; Black Lives Matter and video recordings of police brutality; on photography and agency, and also community; cultural stigma of “selfies” and misogyny, and imperial beauty standards; and photography as “a family building exercise;” then landscape photography in Banff vs. the Kinder Morgan pipeline and how some mountains are more worthy than others; and torture a Abu Ghraib; revenge porn; and what it means to have one’s pain witnessed, corroborated. It’s an essay that ends with questions instead of answers, ever expansive, “Why do we need our lives to be witnessed? Why do we need to share our experiences, to have this connection to others? Why do we need to control others so badly and so completely that we will even try to control their image? Is it because we’re trying to make ourselves more real? Is it because that power—as expansive or minuscule as it may be—fills a void?”

As Olding writes, “the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go.”

While Elliott’s essays—which portray her experiences growing up in poverty, as an Indigenous woman, as the child of a mother with mental illness, a teenage mother herself, a survivor sexual assault—recall (in the best way) the groundbreaking work of Roxane Gay in her collection Hunger—a collection that also lays bare the experience of trauma—they are also different in tone. While rawness is a feature of Gay’s essays in her collection, Elliott’s are more processed, polished, synthesized in a way I hadn’t entirely been expecting from someone who (admittedly, in addition to winning magazine awards, being awarded the RBC Taylor Emerging Writer Prize, being nominated for the Journey Prize, and appearing in Best American Stories, so we should have seen it coming) has made a name for herself with incisive Twitter threads and having none of your racist bullshit on that particular social media platform.

But with her first book—which is eminently readable, absorbing and hard to put down—Elliott solidifies her reputation as a profound thinker and prose stylist, in addition to being a Twitter powerhouse. Perhaps the tweets are where her rawness is, but readers of her essays will find a voice more cool and discerning, and oh-so-fucking smart. Good luck trying to mess with “Not Your Noble Savage,” a consideration of literary colonialism that is coming at you with receipts (as they say on the Twitter), with Margaret Atwood in an essay claiming that Pauline Johnson (as an Indigenous writer) is not “the real thing,” but Thomas King (“the son of a Cherokee father and a Swiss, German and Greek, ie white, mother”) gets to be. “[L]et’s consider Canada’s history of dictating Native identity,” proposes Elliott, and then this leads to considerations of how Indigenous writers’ work is “policed” by critics, and the charade of reconciliation, and “the fairy tale that keeps Canada’s conscience clear.”

Recalling Olding’s, “We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave.”

Oh, the places where these essays take us. She writes about learning the verdict in the Gerald Stanley case, on trial for the killing of Colten Boushie, while visiting the space centre in Vancouver while on vacation with her family, “dark matter” as a metaphor for racism—”it forms the skeleton of our world, yet remains ultimately invisible, undetectable.” I haven’t had lice since February (knock on wood) so was able to read her essay “Scratch” without too much creepy-crawly imaginings. She writes about mental illness, and the Mohawk phrase which describes it, which is where Elliott’s collection gets its name. About being Indigenous while looking white, and her ambivalence about her child receiving the same inheritance; on cultural appropriation and what it meant when she read Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love, the first time she’d read the work of another Indigenous woman—she writes, “Every sentence felt like a fingertip strumming a neglected chord in my life, creating the most gorgeous music I’d ever heard.”

I’ve not even touched on her essay about Toronto’s Bloor and Lansdowne neighbourhood, about gentrification; the one about nutrition, poverty and its colonial legacy; about her marriage (“Antiracism is a process. Decolonial love is a process. Our love is a process…”) About attempting to understand and love her complicated and troubled mother. Her essay, “Extraction Mentalities,” which is a “participatory essay,” something I’ve never encountered before, with literal space on the page for the reader to engage with her questions. And throughout the entire book, really, Elliott has created space to engage with her questions, the entire project infused with this characteristic generosity. To be at once fierce and powerful, but also vulnerable and tender—what a gift that is to her reader. And what a gift this whole book is, strumming a neglected chord that the world needs to hear right now.