October 16, 2020

Petra, by Shaena Lambert

I keep imagining the opportunity to interview Shaena Lambert, and the inevitable question: “So why HAVE you chosen to tell the story of Petra Kelly, German Activist and leading force in the creation of The Green Party in the 1980s?” Though I think I already know the answer, and it’s mainly to do with the expansive possibilities of fiction, and how it can shine a light into dark corners that no archive could hope to illuminate. The limits of nonfiction too for a figure whose mythology was almost as important as the facts of her character. And yet that forty years after her fame and three decades after her death that she’s become an unknown, another woman cast aside under the pounding waves of history. So what does it mean then for me to be encountering Petra Kelly for the first time through Lambert’s fictional lens as I have done while reading her novel Petra? It’s destabilizing, a fictional biography, though perhaps in a way that Petra Kelly herself might have appreciated. Or so I can speculate…

While Petra herself was real, all the other characters in the book are invented, or created as composites of actual figures. The story told from the point of view of a Manfred Schwartz, once Petra’s lover, and then her colleague in government as the Greens are elected to office in 1983 on a rising tide of popularity. Manfred never really gets over Petra, but then Lambert’s Petra is the type you don’t. A German who grew up in America in the 1960s and brings that same idealism to the divided Germany in what would turn out to be the last days of the Cold War—but nobody knew that then. Idealistic, uncompromising, seeing the world and its issues as interconnected as her Marxist colleagues never would.

Defying expectation at every turn, Kelly falls in love with an ex-NATO General, a love story with a sorry end. Which also might be part of the reason why Lambert imagines up the figure of Kelly’s General lover from scratch in her novel, for the unfathomability of his actions. Fiction permitting the author more latitude for the fathoming, imagining this figure who’d grown up in Nazi German, fought for the Germans in World War Two, the atrocities that he would have been party to, and how a person lives with that.

The novel takes the form of a historical record created by Manfred, who is still under Petra’s spell after all these years, and is trying to make sense of what happened between them and of her character in general. A proxy for the author herself, I suppose, and the answer the question I was pondering at the beginning of this review comes with a line near the end of the book, delivered by Manfred’s wife: “Maybe you simply can’t make sense of it all…I mean, maybe it—the past—doesn’t take the form of a thesis.” Which is where the art comes in, the role of literature, to make a sense out of something that doesn’t make sense at all.

By the end of the book, Petra has become a full-fledged spy novel, as we learn who among the Greens had been acting as Soviet agents, this information offering some illumination to Manfred about what had gone on decades before. Petra herself, however, remains somewhat in the shadows, the reader feeling the same frustration experienced by Manfred at how elusive her true nature remains, at how many of her secrets would die with her.

But that she is known through this book, if not actually understood, doesn’t lessen the novel’s impact, and in fact makes it all the more engaging, and in accordance with what actually happens in the world.

October 7, 2020

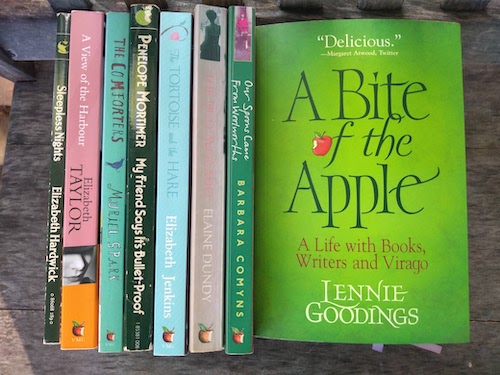

A Bite of the Apple, by Lennie Goodings

This book is everything. A memoir of Lennie Goodings’ 40 years in feminist publishing. The story of legendary Virago Press, which has meant a lot to me and so many other readers. A story of 40 years of feminism too, with fractious debate, changing trends, so much learning and thinking and growing. As a huge fan of mid century British women writers, my own stack of Virago books belies the press’s growing focus on intersectionality, and Goodings writes about that necessary change, her own growth and awareness, and missteps she made on the road to doing better. (It is refreshing to read about an older UK feminist who has not devolved into a raging bigot.)

In a moment of extreme division and polarization, this memoir is a balm. Goodings writes about taking inspiration from Virago author Grace Paley who called herself “a somewhat combative pacifist and cooperative anarchist.” Goodings continues, “Somewhere between these two options—fuck the patriarchy or keep plugging away for what you know is right— is how most women find themselves responding to sexism and inequality we need rage and inspiration we need realism and practical solutions and we need to know our histories literary and otherwise.” There is also the part about about how Decca Mitford and Maya Angelou were devoted friends and did a mean rendition of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”—WHAT???

And most of all, this is a book about books, celebrating the goodness of reading and the connections books forge. I loved it it. Turns out Goodings is Canadian too, and emigrated to England in the mid ’70s. Her book is out this month in Canada, published by the good people at Biblioasis.

September 30, 2020

Brighten the Corner Where You Are, by Carol Bruneau

“Since Maud Lewis’s death in 1970,” writes Carol Bruneau in the Author’s Note to her new novel, Brighten the Corner Where You Are, “her story has become so mythologized it’s just about impossible to separate hearsay from reality, original information from an ever-deepening well of common knowledge.”

And in Bruneau’s own novel, which is based on research and interviews to imagine the inner life of one of Nova Scotia’s most famous and fascinating painters, she attempts no such thing, inhabiting instead an enigmatic space between that doesn’t bother with such distinctions, or emphasize the contrast between Lewis’s bright and floral artistic vision and the realities of her life which were informed by abject poverty, disability, and possible/likely abuse and violence from her husband, Everett Lewis, whose portrayal by Ethan Hawke in the celebrated 2017 film Maudie was more than a little bit generous.

This middle ground is from where Lewis narrates her story, after her death, but still able to see what’s going on in the world below. Now liberated from her disabled body and her marriage, both of which she describes as cages of a sort, but “What these folks don’t see is that these cages made me the bird I am, made me sing in the way I did…”

With rich and artful prose, and a narrative that first appears simple and straightforward and then is revealed to be just a little bit off-kilter (in the style of Lewis’s paintings), Bruneau complicates the myth of Maud Lewis, depicting her as a chain-smoking, deep-thinking, resilient artist who persisted in her vision in the face of adversity, who was an agent in her own destiny just as much as she was a victim of circumstance and impoverishment. Bruneau lets nobody off the hook for this, certainly not Everett Lewis himself, who hoarded the proceeds from his wife’s painting sales and deprived her of luxuries, among them electricity and a flush toilet.

But how could a person with his background (he grew up impoverished himself) have turned out any other way, Bruneau’s Maud insists. And what about the culpability of a society that accepts that poverty is simply a fact, that some lives are worth more than other, whose glaring inequities are as acute as they ever were while Lewis herself was still living.

This book is beautiful, as rich and uplifting as it is a literary masterpiece.

September 23, 2020

If Sylvie Had Nine Lives, by Leona Theis

Okay, imagine the craft and form of Caroline Adderson’s Ellen in Pieces, a premise and scope like Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life, and an attention to the details of ordinary life that recalls the work of Carol Shields? (There’s also a Bronwen Wallace People You’d Trust Your Life To vibe that I can’t quite put my finger on…)

If Sylvie Had Nine Lives, by Leona Theis, is SO GOOD, a novel-in-stories (for real. It works.) that begins in 1974 as nineteen-year-old Sylvie is just three days away from marrying Jack, for better or for worse…

And the book that follows explores the many outcomes and possibilities created by Sylvie’s choices, several forks in the road, and why they matter, or why they don’t. What if life is not a river, the novel’s brief intro suggests; what if it were a delta instead?

Sylvie leaves Jack, and moves in with a roommate whose violent boyfriend’s advances she manages to refuse. Or Sylvie marries Jack and saves his life when he falls into the lake. Or she leaves Jack a few years down the line, pregnant. She marries her best friend from high school has two kids. She marries nobody and starts her own business. She and Jack spend their twentieth wedding anniversary watching the OJ Simpson Bronco chase. Sylvie remains single and becomes a university professor. And so on, these stories showing very different outcomes of Sylvie moving through the decades, getting older, the very same character (one with a propensity for terrible choices) contending with different circumstances.

This premise could be considered a gimmick, but the writing is just so excellent that the whole book shines, and the stories culminate the same way they might in a more traditional narrative. Perhaps some readers could become frustrated with each new story destabilizing what came before, but I just found it really interesting—and it works on a meta level too with Sylvie considering several times the different roads and doors she might have chosen. It is interesting also that the reader would mind at all if the “truth” of a fictional person’s story was undermined—if you’ve read the last page of Kate Atkinson’s A God in Ruins, you’ll know what I’m talking about. Isn’t is amazing that it matters so much? And it’s a sign that the author has achieved something that it does matter.

I’ve not read anything by Leona Theis before, but she’s been shortlisted for the CBC Literary Award, appeared in The Journey Prize Stories, and had the amazing Elizabeth McCracken select her story “How Sylvie Failed to Become a Better Person Through Yoga” as winner of the American Short Fiction contest in 2016, which is the coolest honour I can think of. And this novel lives up to the anticipation of such a biography—the book is wonderful. Definitely my first favourite book of the fall season.

September 10, 2020

Songs for the End of the World, by Saleema Nawaz

When Saleema Nawaz’s Songs for the End of the World was published as an e-book in May, I wasn’t ready for it. I couldn’t do it. A book about a novel coronavirus that sweeps across the world in 2020, beginning in China, and then exploding in New York City. Fiction as uncanny as all-get-out (the novel was written between 2013 and 2019—um, and it includes in its cast of characters a novelist whose book about a pandemic is proving eerily similar to real life events—I KNOW!) but I was having enough trouble facing such things in the world. Plus I don’t have an e-reader…

It was with great hope that I was planning to read the book when it came out in print in August. Hoping the world might seem more recognizable then, Nawaz’s story of a pandemic not quite so close to home, or perhaps that I would be able to put some distance between it and my own situation. And I am so glad that all this transpired, because I liked this novel so much, found it utterly absorbing, and rich.

I suppose it’s not so uncanny how prescient the book seems (it’s Nawaz’s third, following short story collection Mother Superior and the novel Bone and Bread) considering Nawaz based her own pandemic on disease models and intervention strategies. (She was also able to intuit that after a handful of days of quarantine, a person would inevitably order a treadmill.) In a Q&A at the end of the book, she goes into interesting detail about her process, and also writes about how while she didn’t necessarily set out to counter typical disaster narratives, she wanted to “explore…how the stories we tell can influence our behaviour in the real world, for better or for worse.”

(This reminded me of my favourite line from Ali Smith’s Autumn: “…whoever makes up the story makes up the world.” )

What’s most absorbing about the novel is not the pandemic plot, however. First, it is the sentences. “Calamity began, as usual, on an ordinary day. The city roiled with the amplified impatience of a million insomniacs, sleeping children breathed polluted air, low-level exploitation crept across neighbourhoods with insectile persistence, and a thousand everyday kindnesses failed to rise to the surface of consciousness.” How is that for an opener?

And second is the characters, beginning with Elliott, the first responder in Manhattan; Owen, a novelist whose novel appears belatedly on bestseller lists when the pandemic starts; Stu, an indie rockstar whose bandmate and wife, Emma, is pregnant; Sarah, a single mother, who contemplates her future with her child; Keelan, a philosopher whose on work on disasters has resonance for an audience that’s desperate for hope. Moving back and forth between the contemporary moment and pivotal events from the characters’ pasts (young Emma aboard a years-long sea voyage with her eccentric family as her mother freaks out about Y2K), Nawaz has each character singularly navigating the pandemic crisis, but also shows the ways in which these characters’ lives are intertwined in an intricate web, sometimes in ways the characters themselves aren’t even aware of.

She conjures the world in this book, perhaps more specifically than she ever intended, and therein lies the novel’s power. That it’s not the end of the world too—such a lazy cliche. Life and love continue on.

September 9, 2020

Field Notes From An Unintentional Birder, by Julia Zarankin

There are book reviews, and then there are those reviews of books a reader has been waiting a decade for, ever since the first time the reviewer met the book’s author and was presented with an essay collection by Anne Fadiman as a hostess gift. My friendship with Julia Zarankin was forged over the essay form—though she also introduced me to Wallace Stegner. We contain multitudes. And I’ve been wanted to read a book by her since our very first conversation—she was so smart, kind and hilarious. She was working on a collection of essays at the time about being multilingual. Had not long ago abandoned academia for a different kind of life, and she’d recently taken up…birding? It still seemed unlikely then, not yet a fundamental part of her identity. And a couple of years after we became friends, I had the privilege of her contributing a beautiful piece to my anthology The M Word, the final essay in the book.

As Julia’s passion for birding grew and grew, and she began to disappear every spring for migration season.

But now her book is here, Field Notes From An Unintentional Birder, which I loved as much as I loved any of Anne Fadiman’s essay collections, which is saying everything. And I began to think, as I was reading this book, that in her field notes on birding, Zarankin had also written field notes on blogging—all about paying attention, being patient and persistent, not fearing making mistakes, feeling the exhilaration of unbridled passion—and then I realized that what the book was was a field guide to life.

What a terrifically woven collection this so, so much more than the sum of its parts, each of which is wholly impressive. Through the lens of birding, Zarankin writes gorgeously about finding herself in her mid-thirties, divorced and having left her career. So what now? And it’s through birding that she finds the answers, to this, and to other questions, including how to stay in love, how to be brave, how to be comfortable in her own skin, to understand her own history as a migratory creature, how to live in the moment, and how to have purpose. How to be.

Those answers, of course, are not straightforward. Seeing birds does not lead to satisfaction, but instead a yearning for more of them. It means reconciling herself to the birds she’s missed, or those she might never see. But she learns too the pleasures of living in the moment, of being instead of always striving (though an urge to birdsplain is one that’s hard to shake).

The book has general appeal because birding, like blogging, is life—but I also love the details for birding life that Zarankin shares with such exuberance. She shows the peculiarities of the avian world, and the people who are part of it, in perfect, vivid detail.

September 9, 2020

Seven, by Farzana Doctor

A remarkable balance is required to create a novel about Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) that is also a pleasure to read, but Farzana Doctor pulls it off with Seven, a book that is also about marriage, family, motherhood, sexuality, and rediscovering one’s self and purpose at mid-life.

Sharifa has left her job as a teacher in New York City, and travels with her husband and daughter to India, her birthplace, where her husband will be working during his sabbatical. Other than homeschooling her daughter, however, Sharifa isn’t sure how she will spend her time in India, until she decides to partake in a research project to learn the story of her great-great-grandfather, a wealthy philanthropist who was married three times—and in his second marriage was possibly divorced?

Her marriage has just gone through a rocky patch, and so restoring that relationship is also in the forefront of Sharifa’s mind, as she becomes reacquainted with her aunts and cousins, and then realizes that her cousin’s online activism against FGM practices in their Muslim community (“khatna”) strikes much closer to home than she’d ever imagined. Turns out this archaic practice might not be talked about, but it still takes place today.

The different threads of this novel are woven powerfully. and culminate in a terrifically moving story, in particular a scene where Sharifa and other members of their community (including Sharifa’s excellent husband) gather together to publicly protest khatna, disrupting a long-held taboo. There are moments where this novel of ideas becomes much more driven by those ideas than the story itself, but I forgave these , because the book was so enveloping, and Sharifa’s awakening as to her own history was poignant and absorbing, ultimately hopeful and galvanizing. I loved having her voice in my head.

I also loved the historical thread of Sharifa’s great-great-grandfather, and its resonance in the contemporary story line, and how it all comes together so satisfying in the end.

But then the very end, oh my gosh, it destroyed me. The hardest, bravest literary choice, considering the world we live in, and how tidy endings make us too comfortable. I liked this book a lot throughout, but the leap Doctor takes in her book’s epilogue is so awesome and necessary, underlining the urgency of her message—and about how the pleasure we might take in reading this book (while we do) is actually far from the point.

August 27, 2020

Want, by Lynn Steger Strong

Lynn Steger Strong’s novel Want is packed with the same narrative tension that propelled one of my favourite books of last year, Helen Phillips’s The Need. Both of them, as is apparent from their titles, about desperate yearnings, longings, cravings, desires. For an escape hatch, for example, from the demands of motherhood, the feeding, rocking, soothing, waiting. For a way out of the trap of anxiety, a detour away from the trappings of modern life.

Want is less overtly weird, however. There is no sci-fi element, intruder in antlers, no parallel world. Or rather, the parallel world is the one that Elisabeth was promised, a child of affluent parents growing up on the 1980s and 1990s, pursuing her goals in academia, her husband leaving his job in the financial sector after the crash in 2008 to find more meaningful work in carpentry. They build a life in New York, underpinned by dreams and ideals, but it all falls to pieces. As the novel begins, they’re declaring bankruptcy, a process that began with medical and dental bills. She teaches one class at the university, and works 9-5 at a high school, one of those private academies of nightmares. She and her husband sleep in a closet in their Brooklyn apartment, and still can barely afford the rent. She awakes every morning at 4:30 to get the run in that’s so essential to her mental health, and in her downtime, she scrolls social media feeds for clues about the life of her former best friend, Sasha.

It’s not a conventional narrative. It builds and builds, but it also doesn’t, it just goes, the way a life does when you have to wake up at 4:30 every morning in a closet, when you work all day, and are up nursing most of the night. When you’re just barely hanging on, the way that Elisabeth and her husband are, and she keeps thinking back on her history with Sasha, the various ways they both betrayed each other. A story line also builds about allegations against another professor at the university, about Elisabeth’s somewhat agonizing relationship with her own mother, how the effects of a mental health breakdown years before linger still. Unremarked upon are her feelings towards her husband and children, and perhaps these are the only sure things she’s got going here. Everything else is shifting, tricky, impossible to navigate.

There is a sinister banality to Elisabeth’s experiences, one that touches on experiences of race, class and privilege, and there is also a murder, one most unconventional plot-wise, and how all the pieces of the story fit together in the end is the question. They kind of don’t—but also this is the point. Why this puzzle? Why these pieces? And what is the way out of the state that we’re in?

I loved this book.

August 21, 2020

Hamnet and Judith, by Maggie O’Farrell

For YEARS, I have had Maggie O’Farrell confused with the author Catherine O’Flynn, and also I once read another Maggie O’Farrell book (Instructions for a Heatwave) but forgot about it completely, so I wasn’t exactly primed to pick up her latest, Hamnet and Judith, especially since it’s set in the sixteenth century and is about Shakespeare. No thank you.

And yet?

Then I kept reading reviews about it, and I can’t recall exactly what swayed me, but it was something about the universality of the fiction, and the glowingness of all the raves. And so I bought the book when we were at Lighthouse Books last month, and I loved it so completely, reading it a few weeks later when we were camping at Bronte Creek.

Which was two weeks ago now, and this week has got away from me. It is 5:31 pm on a Friday as I write this and I have to go make diner, but first, I want to put down on the record that this is perhaps the finest book you’ll read this year. Oh, the writing! The sentences! The scene in the apple store, those pieces of fruit bop-bop-bopping on the shelves to a rhythm. The whole world so magnificently conjured, and yes, it was the universality. It doesn’t matter that this was Shakespeare’s family (in fact the bard himself is not even named), or the century where the story is set—there was an immediacy to the narrative that I so rarely experience in historical fiction. Perhaps because the story is written in the present tense, but it works, the people, the scenes, so alive, so achingly, complicatedly real. And yes, the heartache, for this is the story of a child who dies, and the family who must suffer this incalculable loss, and this universal. The unfathomability. The fear as well, for this is a story of plague, and it seemed especially resonant as I read it in the summer of 2020. And the chapter about how the plague arrived in Warwickshire, fleas, and beads, and ship cats, the way that one thing leads to another, how everything is connected.

A truly magical, and stunning read.

August 10, 2020

The Vanishing Half, by Brit Bennett

A literary highlight of my week away in July was Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half, the follow up to her smash-hit debut The Mothers, which was one of my favourite books of 2016. A novel that reaches across lines of race, class and gender, across history, across an entire nation…to tell the story of a pair of twin sisters who run away from the southern town they come from, a community of light-skinned Black people. And then years later, in the summer of 1968, one of the sisters returns with her daughter, to live out her life where she started. Ironic when she’s the one who wanted to be an actor, but it’s her twin sister who—as we learn in the rest of the book—spends the rest of her life passing as white, enacting her suburban ennui in an upscale California neighbourhood, like a character in a 1970s’ Joan Didion novel. And what happens when the two sisters’ children become connected years later? Whole lifetimes unfurling from a connection that cannot be severed, a fascinating story of halves and doubleness, infinitely satisfying.