February 14, 2022

Free Love, by Tessa Hadley

Free Love was in the air—I’d heard about the book’s release in the UK, and anticipated a delay before it becoming available in Canada, but there it was, on sale February 1, and so I ordered it. Before the book arrived, another friend was already posting about it on Instagram with a rave review, and then the day I finally started reading, another friend sent along an email telling me that it was one of the best books they’d read lately and that I really must pick it up, and I do so love being told what to do when I’m doing it already.

Tessa Hadley is newish to me. I’ve read her novels The Past and Late in the Day in the last few years, and really enjoyed them, and have been looking for other copies of her books in bookshops ever since, but they’re not widely available here in Canada. It’s also true that while I enjoyed both books, they didn’t leave overwhelming impressions on me and I can’t remember much about either one except that they had atmosphere. And I think that’s actually the point.

Because Free Love too is an atmospheric novel, a book full of tension and interiority instead of wildly swinging plot. And even when the plot does swing with housewife Phyllis abandoning her suburban life to pursue a relationship with the bohemian son of a family friend, or even before that when fate conspires to bring this unlikely couple together in the first place, kissing beside a garden pond on the hunt for an errant sandal, the earth barely shakes and life continues on, seasons changing, floors requiring sweeping, dinners making. Everything is changed, but also nothing at all—but then about two thirds of the way through there comes a revelation that blows everything apart, and has me texting the friend who’s read it already “OMG I JUST GOT TO THE PLOT TWIST!”

But it’s not in fact the plot twist that matters at all really, instead the rhythms and patterns of daily life, both before and after, that Hadley manages to capture so beautifully, the way that life goes on, and on—if you’re lucky—no matter your choices. Every moment itself is a narrative leap.

January 28, 2022

All Is Well, by Katherine Walker

The premise of Katherine Walker’s debut novel, All is Well, hooked me immediately: Christine Wright, former special forces agent and a recovering alcoholic, is settling into her near career as church minister when things go wrong and she ends up with a body to dispose of.

There’s a novel I’ve certainly never read before.

There’s also the sentient candlestick with ties back to Julian of Norwich, the excellent women who do the behind-the-scenes work at the church, the deranged vegan nurse with a daughter named after pate, the military policeman who’s intent on bringing Christine down, and all of Christine’s own demons resulting from childhood trauma and a military operation in which three members of her team were killed.

I loved this book, which is heartfelt and hilarious. A little bit screwball, and more than a little mystical, kicking at the margins of plausibility, but it works, it’s so novel, and so cleverly executed. No matter how determined Christine is to be at a remove, to not let anybody glimpse her vulnerability, Walker writes her character’s way right into the reader’s heart and the emotion is real, if everything else becomes something of a farce as the church community begins to grow and change, manifesting into something extraordinary under Christine’s tenure, in spite of all her attempts to stay under the radar.

No doubt this is a novel wholly imagined but informed by its author’s experiences in the Royal Canadian Navy and as a graduate student in divinity, which results in a really thoughtful foundation to this comic novel. This is one of those “fasten your seat-belt and hold on” novels, because it all moves pretty fast, but All is Well is also a book that’s rich in meaning, about trauma, and healing, and the possibilities of redemption.

Don’t miss it.

January 7, 2022

The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, by Eva Jurczyk

Eva Jurczyk’s debut novel The Department of Rare Book and Special Collection ticks all my boxes—bookish mystery, rare book thieves, library setting, weirdo librarian characters, Toronto setting, and intriguingly feminist. Curiously, Jurczyk arrived at the idea for her book and her protagonist Liesl after she became a parent and began pondering the invisibility of women, specifically older women…and then she went and wrote a novel about a woman who’s about sixty, which isn’t the usual trajectory for a new mom/novelist, is all I’m saying.

And so Liesl was not who I was expecting, especially based on the book’s otherwise quite compelling cover which might mislead a reader (and it certainly did me) into thinking I wasn’t picking up a book about a character with decades of backstory behind her, a story about a woman in a long marriage with a grown daughter, a woman on the verge of retirement with plans of finally writing that book about gardening she’s been thinking about all these years.

But then plans get called off when the Director of the Rare Books Library (which may or may not be influenced by the Thomas Fisher…) where Liesl works is incapacitated by a stroke, and she has to step into acting in his role. Which her colleagues are put out by, never mind the university president with his ubiquitious bike helmet and obsequious regard for major donors. All of which would be annoying enough, but then Liesl begins to realize that things at the library are not what they seem, that any number of her colleagues could be keeping secrets, and then one of those colleagues goes missing, but no one wants Liesl to involve the police.

The bookish mystery here is fun and interesting, though it’s Liesl’s own story that’s most remarkable and compelling about this book, and I admire the deft way in which Jurczyk sets her character just past midlife (don’t tell any baby boomers I wrote that…) and yet manages to develop a rich and textured backstory without awkward exposition. Liesl’s relationship with her husband John is my very favourite part of this book, such a deep and sensitive portrayal of a long and complicated relationship. John has struggled with depression over their years together, the reader is able to understand, and I kept waiting for this to become a plot point (and so does Leisl, actually, ever aware of how the bottom can fall out) but (SPOILER ALERT) it really doesn’t.

I don’t know that I’ve ever read a novel before in which loving somebody with mental illness is incidental to the story, but also it informs our understanding of Liesl, and her experiences with John in the past will inform the challenges she encounters at work where she feels like she’s been stymied at every turn.

The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections was my first book of 2022, and it started off my literary year on such a high note. Even better? On January 21 at 1pm, I’ll be interviewing Jurczyk for her virtual event with the Toronto Public Library. You can register here if you’d like to attend. I’m really looking forward to it.

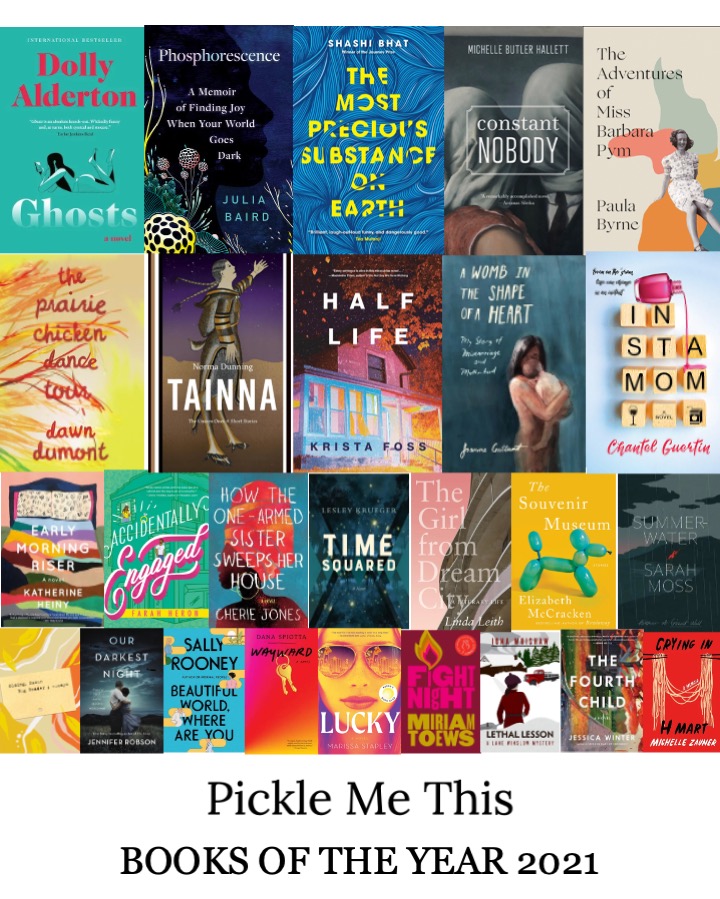

December 15, 2021

2021: Books of the Year

- Ghosts, by Dolly Alderton

- Phosphorescence, by Julia Baird

- The Most Precious Substance on Earth, by Shashi Bhat

- Constant Nobody, by Michelle Butler Hallett

- The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, by Paula Byrne

- The Prairie Chicken Dance Tour, by Dawn Dumont

- Tainna, by Norma Dunning

- Half Life, by Krista Foss

- A Womb in the Shape of a Heart, by Joanne Gallant

- Instamom, by Chantel Guertin

- Early Morning Riser, by Katherine Heiny

- Accidentally Engaged, by Farah Heron

- How the One Armed Sister Sweeps Her House, by Cherie Jones

- Time Squared, by Lesley Krueger

- The Girl From Dream City, by Linda Leith

- The Souvenir Museum, by Elizabeth McCracken

- Summerwater, by Sarah Moss

- Big Reader, by Susan Olding

- Our Darkest Night, by Jennifer Robson

- Beautiful World, Where Are You, by Sally Rooney

- Wayward, by Dana Spiotta

- Lucky, by Marissa Stapley

- Fight Night, by Miriam Toews

- A Lethal Lesson, by Iona Whishaw

- The Fourth Child, by Jessica Winter

- Crying in H Mart, by Michelle Zauner

December 1, 2021

4 Great Memoirs I Rushed To FINALLY Read Before Year’s End

A Womb in the Shape of a Heart, by Joanne Gallant

Joanne Gallant’s A Womb in the Shape of a Heart is a story of motherhood and loss, a motherhood story that didn’t always promise a happy ending either, though Gallant had no inkling of this when she and her husband set out to have a baby. A pediatric nurse, a person who’d always seem in control of her own destiny, the grief and powerlessness of miscarriage and infertility would rock Gallant to her core.

A Womb in the Shape of a Heart is a beautifully woven story of loss and love, Gallant eventually giving birth to her son, but the pregnancy was fraught with anxiety, and the early days of his life were spent in the newborn the intensive care unit.

And it’s just a story so gorgeously crafted, honest and brave in so many ways, a story that encapsulates the experience of so many families but is still considered taboo or shameful. Joanne Gallant shattering that stigma with beautiful prose and such compelling storytelling that will assure so many people that they aren’t alone.

Persephone’s Children, by Rowan McCandless

All right, this book is excellent. Which is remarkable because a collection of “fragments,” you’d think, would be inherently raw and unpolished. Especially when the fragments themselves are so curious in form: the essay as crossword puzzle, as drama script, as quiz, as diagnosis.

Pretty cool, right? A fun gimmick. But challenging to execute…

In her debut collection, however, Rowan McCandless gets it right, each of these pieces so meticulously crafted to tell a story of a difficult childhood, of growing up Black and biracial, of surviving and escaping an abusive marriage. She writes about motherhood, mental health, and living with trauma.

This is a book that’s going to surprise and delight you.

Any Luck At All, by Mary Fairhurst Breen

Any Kind of Luck at All, by Mary Fairhurst Breen, is from one of my favourite literary genres: memoirs by women who’ve seen some shit. She writes about her suburban childhood, her father’s unspeakable mental illness, her burgeoning activist experiences, marrying young and perhaps unwisely, about parenting as her husband’s addictions overtook him, of becoming a single mother, a lesbian, of a career in nonprofits subject to the whims of government funding, of the struggles of finding work as a woman who’s over 50, and of supporting her daughter through her own mental illness and losing her to fentanyl poisoning in March 2020. Breen originally started writing down her stories for her daughters to read, and as a result they are told with such warmth, and are candid, breezy, funny, and wise.

Fuse, by Hollay Ghadery

I enjoyed Hollay Ghadery’s uncomfortable-making, complicated, richly textured collection of essays, a memoir of daughterhood and motherhood, mental illness, eating disorders and biracial identity SO MUCH. Most things are not just one thing or another, but instead both, and neither, and everything at once. In Fuse, Ghadery unapologetically demands the right to have it both ways, to be a messy, conflicted, raging, loving, hungry and full to bursting human

November 18, 2021

Time Squared, by Lesley Krueger

Okay, speaking of time, I have but fifteen minutes in which to write this post before I have to take my daughter to the dentist, and so I’ll dive right in and tell you that that novel, Time Squared, by Lesley Krueger, which I’ve loved more than I’ve loved than any book I’ve read in ages, could be billed as Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life meets Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, if we wanted to underline just how badly you really ought to read it. And oh, you really do.

The beginning is kind of strange and discombobulating, but the reader eventually realizes there is good reason for that. Eleanor, a young woman in the nineteenth century, is being groomed for marriage, finds herself falling in love with Robin/Robert, the younger brother of the man her aunt is hoping she will marry in order to ensure security financial and otherwise. Robin is on the eve of leaving to fight in the Napoleonic War, and over the course of the novel, Eleanor, and her aunt, and her friend Catherine, and other members of their families and community, bide their time as battles prove inevitable, and Eleanor waits for the man she loves to come home.

Except that she keeps finding herself moving about curiously in time.

The plot unfolding, relationships growing, deaths, and heartaches, and other losses, but sometimes it’s the early nineteenth century, and sometimes it’s the Victorian age. Sometimes Robin is fighting in the Boer War, WW1, the London Blitz. Sometimes they’re in mid-century America against the backdrop of the Korean War, the war in Viet Nam. A few strange glimpses of even earlier times, the 14th century. 61 A in Londinum.

And Eleanor is getting these glimpses, seeing these visions which she cannot possibly understand, which are written off as migraines, or perhaps something more troubling. Accustomed—as a woman, as an orphan, as a person whose financial destiny is precarious—to being moved about by others as if a pawn, until finally she gets tired of being played, and makes the decision to finally confront her masters.

Oh my gosh, this book is excellent. It takes some time to find its way into, because its unstable narrative is the very point, but it’s always interesting, underlined by literary allusions in the most delightful fashion, but by about midway through, I was finding it very hard to put it down. Last night I had to stop reading around page 250, because I had to go to bed, but then I couldn’t sleep, my mind all wrapped up on the narrative and just where the narrative is going.

And it’s going somewhere so perfect, a story that cannot possibly just be a cheap gimmick in the end, and it isn’t. Oh the ending, I loved the ending, so absolutely perfect, that last sentence the most extraordinary gift and promise.

November 12, 2021

Wayward, by Dana Spiotta

I recently read Dana Spiotta’s novel Wayward in one sitting, not necessarily because it was it was unputdownable, but because I’d chosen it for the Turning the Page on Cancer Readathon a few weeks back. And it turned out to be a perfect selection for such a thing, the novel utterly absorbing, although I read it kind of deliriously, now that I think about it. It’s a pretty intense novel with a whole lot to unpack, and so the affect of reading it all in one burst was a bit like being smacked in the head with a baseball bat, but in the very best way possible.

It’s a highly specific novel about something so many of us tend to speak about in general terms, namely what happened when the world went off the deep end in 2016. For Samantha Raymond—whose mother is ailing, whose daughter is coming of age, who suddenly finds herself unable to sleep at night—this surreal moment in the universe sends her life into a tailspin when she decides to leave her comfortable suburban home, and her marriage, purchasing a ramshackle historic home in a dodgy neighbourhood in Syracuse.

The first line of the novel: “One way to understand what had happened to her (what she had made happen, what she had insisted upon): it began with the house.”

“It began with the house” could well be the opening line to most novels that I love.

Wayward is a twisty, tricky novel, that’s also about mid-life, aging, about feminism, about white feminism, about cities, neighbourhood, community, motherhood, daughterhood, about notions of justice and what it means to lead an authentic life. As can be expected from the title, Sam’s pursuit of such a thing is not straightforward, usually ill-advised, and hers is a story of mistakes and wrong-doing, the inevitability of these, the impossibility of purity, of the possibilities of redemption.

November 4, 2021

The Prairie Chicken Dance Tour, by Dawn Dumont

I’ve gone back in my archives to remember when it was that Dawn Dumont, from the Okanese Cree Nation, became one of my favourite Canadian authors, and turns out it was 2015 when I read Rose’s Run, “a book that’s funny, breezy and heartwarming, and then manages to include a terrifying demon in the mix who feeds on the strength of women, so I was hooked in a cannot-turn-out-the-light-until-I’m-done kind of way, an I’m-going-to-have-nightmares kind of way (and I did!)…”

She followed up Rose’s Run, her second novel, with Glass Beads two years later, a novel in stories in which the demons were less literal, the narrative tracing four friends through decades of their lives, loves and losses, ups and downs, a novel that similarly irreverent if more realist, as well as heartbreaking and hilarious at the very same time.

Heartbreaking and hilarious is a tricky balance but in her fourth fiction release, Dumont has done it again. The Prairie Chicken Dance Tour is set in 1972 as food poisoning has taken down the Prairie Chicken dance troupe on the eve of their European tour, cowboy John Greyeyes reluctantly agreeing—even though he hasn’t danced in years—to lead a cobbled-together team of subs as a favour to his brother who’s Chief of the Fineday Reserve. (Politics factor large in all Dumont’s novels; she also served as a Liberal candidate in the September 2021 Federal election, something else on her CV now, in addition to novelist, lawyer, and stand-up comedian).

As can be expected of any novel that begins with diarrhea and features a hijacking within the first three chapters, The Prairie Chicken Dance Tour is indeed a string of madcap adventures, funny and ribald, over the top and unconstrained, and unrelentingly amusing. Greyeyes has to contend with a young dancer who flirts with anything that moves, her uptight Catholic auntie, plus a fourth member of their group who isn’t who he says he is, not to mention the original leader of the dance troupe whose stomach has finally recovered and is on her way over to Europe to take up the job that should have been hers to begin with.

The book is fun, but it also pulls no punches. Set in 1972, its main characters are survivors of residential schools in a country that has not even begun to reckon with this, living with the trauma and broken bonds of these experiences. Dumont showing too that every person who’s able to survive has their own way of doing so, which can be complicated, as is the case with Edna, who finds strength and solace in the Catholic church and whose processing of her experiences doesn’t immediately make sense from the outside.

But Dumont shows us each of these characters from the inside, deftly using fiction set fifty years ago to consider ideas and issues of racism, cultural genocide, and the possibility of reconciliation that have never been more timely. Using humour too to diffuse the pain, to create the chance for some kind of happy ending.

November 2, 2021

Good Burdens is here!

If my Blog School course had a textbook, Christina Crook’s Good Burdens would be it, a heartful and inspiring book about living a mindful and joyful digital life. After blogging for more than twenty years (and using my social media platforms as an extension of my blogging space), I know that the tools of the internet are capable of making our lives richer and deepening social connections, but that involves considered and deliberate practice, a willingness to go against the grain and serve ourselves (and each other) instead of an algorithm. And the payoff? A meaningful online life whose riches spill over into the real world in the form of friendships, inspiration, and creative work.

What is a Good Burden? Our good burdens are the work we do to that add meaning to our lives—partaking in a community project, putting dinner on the table where family will gather, sending a card or a letter to a friend. In a world where technology promises endless ease and convenience, it’s too simple to forget how much these kinds of gestures matter, both to our communities and to ourselves.

And in Good Burdens, Crook shows that the notion of good burdens can bring light and meaning to our digital experiences, and also to the rest of our lives. She urges her readers to pay attention to the world around them and to those things which deliver joy. What is joy and how do we find it? How do happy people use technology differently than other people? What makes a good life? How do you get there?

The book is a warm, inviting and engaging read, but also structured as a workbook with space for readers reflect and write down ideas, offering personalized approaches instead of one-sized-fits-all solutions, urging us to ask ourselves the right questions instead of promising answers. Good Burdens is about ideas that I think about a lot, but I still found it rich and inspiring—and really enjoyed the opportunity to talk with Crook on a recent episode of her JOMOcast all about the spaces where her ideas and my own blog thoughts overlap.

I first read this book as an advanced reader copy, and liked it so much I pre-ordered a finished copy, and then the publisher sent me a finished copy, so now I have two! If you would like the chance to win a copy of Good Burdens, make sure you’re signed up for one of my newsletters (sign up for the Pickle Me This Digest or the Blog School Newsletter) for a chance to win my spare copy. If you’re on my mailing list already, watch your inboxes—coming Friday!

And if you just can’t wait, you can go to your local bookstore and pick up Good Burdens today.

October 31, 2021

Hauntings: Books That Won’t Leave Me Alone

I loved this book, which I thought was going to be a smart and funny novel about modern dating and the phenomenon of “ghosting,” which it was, but it was also so much richer and more meaningful than that as Alderton’s protagonist comes to understand the different kinds of ghosts that are haunting her experience—ghosts of a past romance, of her childhood, and also of her relationship with her parents, which is changing and becoming more complicated as her father’s dementia progresses.

*

Reading the latest Laura Lippman is a summer holiday tradition for me and my husband. We love her, and her latest, a literary homage to Stephen King’s Misery, is a marvelous mindfuck. Lippman moves from crime fiction to psychogical thriller in this novel about an author who becomes confined to his bed and then proceeds to be haunted/hunted by a character from one of his novels. We loved it, and the meta elements of it all were delicious.

*

The Other Black Girl, by Zakiya Dalila Harris

This one checked a lot of boxes for me—set in the publishing industry, biting social commentary, and twisty and weirder than you’d think, billed as “Get Out meets The Stepford Wives.” Naturally, Nella is pleased when the new hire at her office means she’ll no longer be the only Black girl at her publishing company, but her comradeship with Hazel turns out to have an edge. The novel is a statement on racism and feminism, the notion of how much progress is enough, and a culture of scarcity that means supporting others could mean hindering one’s own chances of success. But it’s also more than that, totally bonkers, involving an underground movement, and a fight back after decades of oppression.

*

Malibu Rising, by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Everyone keeps telling met that the The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo is her best, but I haven’t read it yet. I did read Daisy Jones and the Six and liked it well enough, but I LOVED Malibu Rising, a holiday dream of a novel that I read in a single day and then forced until my husband who liked it as well as I did. Complicated family dynamics, Americana, California, and the sea. The novel had some furious momentum and I found it unputdownable. I can’t think of any literary ghosts in this one, but characters are indeed haunted—by lost loves, and the people they used to be.

*

A Thousand Ships, by Natalie Haynes

We read The Odyssey earlier this year, and I ordered this book afterwards, inspired by that book and also events in The Iliad, though I confess that I wasn’t chomping at the bit to read it, figuring it would be difficult. Those Greeks, you know? But I loved it. Read it right after Malibu Rising and just as quickly while we were on holiday this August, and then my husband read it, and then our daughter did, and it brought these characters to life in the most vivid, devastating way, because this is a novel about death and loss and destruction after all. There is nothing heroic in these wars, which tell the story of how their experienced by many different women. I can’t wait to read The Iliad now