May 8, 2016

On Mother’s Day

Sunday morning, and I am reclining on the spine of a very, very good weekend, late Friday night aside. I can’t tell you about Friday night because I am a mother who makes a point of keeping my children’s dignity intact, but my goodness, what a story I could tell you over a nice cup of tea. Motherhood is lousy with unsavoury, monstrous things, when it’s not blinding with moments of pure, shining light. But we’re thirty six hours after that now. I spent yesterday in Brampton at The Fold Festival, with three wonderful friends keeping me company on the road and throughout. The day was inspiring and terrific, and I can’t wait to tell you all about it. I arrived home last night to dinner on the table, and a happy rest-of family who’d spent their own very good day together.

And now today is Mother’s Day, and I find myself appreciating my own mother even more than usual for how she saved our family when I was ill last December and cared for my children for a week this winter so my husband and I could celebrate our tenth anniversary in tropical climes. Where would any of us be without her? Certainly never, ever in Barbados. But as my mother is across the country today with her other favourite daughter and other favourite grandchildren, I get to be the star of my own show. Which means breakfast in bed and reading so many papers that my thumbs turned black. Iris gave me a flower she’d planted at playschool, and Harriet gave me a painting she’d made of irises, so floral is the theme. And Stuart gave me a book and a teacup, so he knows me well too. And what I want for the rest of the day is to make soup for lunch (I have become addicted to my immersion blender), to spend some time cleaning up the leaves and seasonal detritus from our backyard, and a little bit of hammock time. Followed by dinner at my favourite restaurant.

This morning I was brushing my teeth and perusing the row of books lined up beside my bathroom sink, and figured it was a good day for a flip through White Ink: Poems on Mothers and Motherhood, edited by Rishma Dunlop, who died a few weeks ago—Priscila Uppal’s eulogy for her friend is extraordinarily good. And I came to the poem “On Mother’s Day,” by Grace Paley, which is tangled, beautiful, sad and very funny, just like motherhood, just like life is. And I am so glad I did…

Suddenly before my eyes twenty-two transvestitesin joyous parade stuffed pillows undertheir lovely gownsand entered a restaurantunder a sign which said All Pregnant Mothers FreeI watched them place napkins over their belliesand accept coffee and zabaglioneI am especially open to sadness and hilaritysince my father died as a childone week ago in this his ninetieth year

January 5, 2016

Lottie: Empowering Girls from Outer Space

We discovered Lottie Dolls over a year ago, and their premise intrigued me. A proper alternative to Barbie, designed to empower girls and their play. I wrote about them here (and check out the pictures! Iris was still a baby! Harriet was so little). It could have been a one-time thing, but I return to Lotties because now it’s my girls who are crazy about them. They’re the one toy, along with Legos, that gets returned to again and again, and they play with them together, which I love so much. We have five or six of them, and received more for Christmas, along with two new Lottie outfits, including the Superhero Lottie suit shown above, which has proven very popular—this is the one Lottie who never gets her clothes changed. When Harriet and Iris received Christmas money from their grandfather last week, they knew what they wanted to buy with it—more Lotties. And so we’re currently awaiting Rockabilly Lottie and Spring Celebration Ballet Lottie in the mail, expected delivery scheduled for tomorrow. Everybody is very excited.

Though we’ve also got our eye on Stargazer Lottie, who was sold out from Indigo.ca when we made our order last week. (Darn!). Like all the Lottie dolls, she’s designed around what she can do and be rather than how she looks (although admittedly, once they’re indoctrinated into Harriet’s play, the Lottie dolls also take on peculiar new identities…) I was so interested to read this post about how Stargazer Lottie was designed in consultation with an astronomer, and even more thrilled to learn that a Stargazer Lottie doll was currently in space with British astronaut Tim Peake on the International Space Station.

And most remarkable? That none of this would have happened at all without a six-year-old girl from Comox, British Columbia, who helped dream up the Stargazer Lottie doll. I showed the video below to Harriet who had her mind blown, and then went to put on her own dress with a space print and proceeded to have her head in the stars for the rest of the day, totally inspired.

December 11, 2015

The Places I’ve Been

The best news is that I’m finally getting better, and I’ve even been to a place lately that isn’t my bed—last night I ventured out to Harriet’s holiday concert to hear her sing in the Primary Choir. This weekend, we’re planning to hang up the Christmas bunting, and the plan is that by mid-next week, I might be up and about in the world again. But until then, and even after, we’ll be taking it slow. The nice thing about the Christmas holiday is that it’s a perfect time to have that happen.

The best news is that I’m finally getting better, and I’ve even been to a place lately that isn’t my bed—last night I ventured out to Harriet’s holiday concert to hear her sing in the Primary Choir. This weekend, we’re planning to hang up the Christmas bunting, and the plan is that by mid-next week, I might be up and about in the world again. But until then, and even after, we’ll be taking it slow. The nice thing about the Christmas holiday is that it’s a perfect time to have that happen.

But other things have been happening as well, perhaps sustaining the illusion that I’ve been more active lately than I actually have been. First, the Winter 2016 issue of U of T Magazine is being mailed out soon, and it includes a short piece I wrote about the curious trajectory of my life in blogging. I wrote about how I started blogging at a point when blogs were poised to take over the world, which never quite happened, but for me (and for many others) blogging has played an enormous role in my career and evolution as a writer and a person, even. Blogging has sustained me during periods of high and lows, and through the throes of literary disappointment, and it’s now integral to my process—so much so that my forthcoming novel is about the secret life of a blogger. I was really grateful for the opportunity to write this article, and you can read it online here.

For Understorey Magazine, I got to be part of a conversation with Ali Bryan, Alice Burdick, Lorri Neilsen Glenn, Natalie Corbett Sampson, Natalie Meisner, Shalan Joudry, and Sylvia D. Hamilton about whether it’s possible to be both a mother and a writer at once. (Spoiler: I say YES). There’s lots of great advice, stories and wisdom from women who’ve been there, and I love the effect of so many voices together. I love this line from Sampson: “Shutting the world and your experience out in a ‘no diversion’ and ‘no intrusion’ approach leaves you open to missing things that can be shaped into stories. ” Naturally, I encourage women to let their children watch Annie all summer long in order to get that novel written, which worked for me. Read the whole thing here.

And finally, I took part in a very fun conversation with Corey Redekop about what happens when a wonderful writer turns out to be a terrible human being. Examining my own bookshelves, I really couldn’t find a single horrible human being among them. My authors are mainly crotchety old women, which many people construe with horrible human beinghood, but crotchetiness is these writers’ entitlement, I think. I love them better for it. Anyway, we talked about whether being an asshole was a male writer thing, I refer to Barbara Pym’s Nazi sympathies, we discuss what red lines are for us as readers (not Nazi sympathies, apparently…) and what if Rush Limbaugh was authoring the next The Phantom Tollbooth. You can read it all here.

See? I have been busy.

September 10, 2015

It begins.

I got pregnant at nearly the exact same time as Harriet started playschool three years ago, when she was three years old. And I so vividly remember those precious mornings, the time, rushing home to rescue my tea from under the cozy and sit down to get some work done, not wasting a single moment. To be alone. Although the time did not seem so luxurious: I was in my first trimester and would pass out every night not long after Harriet did. If I hadn’t had those mornings, I would have had no time to get any work done. After Christmas when my energy levels had returned, I got a job writing a book about Arctic exploration, the gold rush, mountain climbing, and parkas, and by then my days of freedom were numbered anyway. So I spent that winter reading Pierre Berton on the Klondike and listening to Iris by the Split Enz over and over again, dreaming of my baby as she kicked away inside me—so you see, I was really not so alone at all.

It seemed like the smallest window, that year. I knew that with our new baby, we’d soon be thrown back into newbornland and babyhood, and we’d have to find our way out again. That it would be a long before I once more found myself at home alone at 9:30 in the morning, the teapot still warm. I edited an entire book as the baby slept on my chest, for heaven’s sake. And now, here I am. And dare I say it: it all went by so fast?

This morning I dropped Harriet off at Grade One, which she is enjoying immensely so far, and then Iris and I trekked down the street for her to begin her first day of playschool. The playschool she has known since she was a fetus: she spent her first year in her carrier as I did co-op shifts three times a month. By the end of the year, she was scooting around the room like a champion. It has always been familiar to her. We love the teachers. Last year when Harriet was no longer a student there, we still visited our playschool friends often, and we’d play with them at the park.

Drop-off was not without its drama. Iris was not happy about my departure, and while I wanted to get out of there and trusted she was in very good hands, I’m a bit worried about the teachers who’ll have to deal with her. Though I assure myself that perhaps like all parents, I’m imagining that my child is more unique and particular than she actually is. I’m crossing my fingers that they’ve seen it all before. And that she’ll have a wonderful morning.

And now here I am, right back where I’ve been before except that this is the way forward instead of just a blip. It’s even time to put the kettle on. It’s time to get some work done. To figure out this new routine, just what to do with all this space and this quiet.

See also: “When I got home again, I didn’t know what to do because there was so much that I wanted to do.”

May 20, 2015

Survival Gear for Our Stories

A lot went wrong when my first child was born, most of it involving the loss of my mind, but there was also the fact of the loss of my hard drive when the baby was four weeks old. I lost everything on my computer, which was actually kind of liberating—this all happened on the day I turned 30, and I was intrigued by the idea of a fresh start, a clean slate as I embarked upon a brand new decade. The only thing we lost that I truly regretted were photos, unflattering ones taken soon after the birth, photos of us in the recovery room as we were learning to breastfeed for the very first time. These were the kind of photos one wouldn’t post on Facebook, all bare boobs and double-chins, and besides, I was still then the kind of person who didn’t want to put too many pictures of my child on Facebook. I didn’t want to be one of those people.

A lot went wrong when my first child was born, most of it involving the loss of my mind, but there was also the fact of the loss of my hard drive when the baby was four weeks old. I lost everything on my computer, which was actually kind of liberating—this all happened on the day I turned 30, and I was intrigued by the idea of a fresh start, a clean slate as I embarked upon a brand new decade. The only thing we lost that I truly regretted were photos, unflattering ones taken soon after the birth, photos of us in the recovery room as we were learning to breastfeed for the very first time. These were the kind of photos one wouldn’t post on Facebook, all bare boobs and double-chins, and besides, I was still then the kind of person who didn’t want to put too many pictures of my child on Facebook. I didn’t want to be one of those people.

The baby had only been around for four weeks, but those early weeks are such times of enormous change. At four weeks, she’d already amassed multitudinous selves, passed through several incarnations, and it was impossible to keep track of all them. And most of that was irrevocably lost when my hard drive went kaput, taking all my photos with it. Except, ironically, for the few photos I had posted on Facebook—an exercise I’d undertaken with remarkable restraint. And suddenly, those few photos were the only ones I had. Facebook was my saviour—who’d ever have imagined?

So I was converted by the time my second daughter was born four years later. There were going to be so so many pictures. We were also going to have her photographed immediately after her birth by ceasarean, all purple and gloopy and as foetal as she’d ever be again. I wanted to see it. I’d missed it before, when Harriet been all cleaned up and wrapped in a blanket before I saw her at all, her father by my side reporting that, “Our baby has so much hair.” There had been a gap between her birth and her life that I was never able to get over, the medical screen never really coming down, and perhaps I’m just coming up with metaphors to explain my failure to process that this child was mine, but there it was. I wanted pictures this time. Of all of it. I didn’t want to miss a single thing.

When Iris was a few weeks old, my computer began to fail again, laptops seeming to have a similar lifespan to the space between my children. But we’d learned our lesson and backed up our photos, so that all of them now live on a portable hard drive. Which means they’re inconvenient to access, but they’re there. And I pulled them out not long ago to prove my case in point

“Words and pictures—survival gear for our stories,” writes Myrl Coulter in her memoir, A Year of Days, and I underlined that part. Survival gear indeed, for when I started looking at photos—hundreds of them—from the days after Iris’s birth, I scarcely recognized any of the moments documented within. At least not at first, but then the memory of these moments started returning to me. Mundane things that would be of no interest to anyone but me, for whom they’re unbearably precious—photos of me lying in bed at home with my children, who were discovering each other as sisters; crazy eyed bloated fat face photos from post-op; breastfeeding pics galore; and even a photo my incision just before the staples came out, because I couldn’t actually see it and was unbelievably curious.

“Words and pictures—survival gear for our stories,” writes Myrl Coulter in her memoir, A Year of Days, and I underlined that part. Survival gear indeed, for when I started looking at photos—hundreds of them—from the days after Iris’s birth, I scarcely recognized any of the moments documented within. At least not at first, but then the memory of these moments started returning to me. Mundane things that would be of no interest to anyone but me, for whom they’re unbearably precious—photos of me lying in bed at home with my children, who were discovering each other as sisters; crazy eyed bloated fat face photos from post-op; breastfeeding pics galore; and even a photo my incision just before the staples came out, because I couldn’t actually see it and was unbelievably curious.

I’d forgotten all of it, which is natural, I suppose, and it’s possible that it’s unnatural to have so much documentation, that it may tax our minds to have so much evidence of… of what? Of life, I suppose. And these photos bring it all back so clearly. Having taken them certainly does not mean that I was any less in the moment (and really, being a mother is to be eternally in the moment no matter how you try to swing it). If it had only been about the moment and not its preservation, those memories would have been lost altogether.

There has been a lot of criticism thrown at my generation, and those younger, for oversharing, for selfies, for self-absorption, and toward mothers in particular for conspicuously mothering on social media. (This is a criticism I was responding to when I resisted baby photos on Facebook so many years ago). But the idea of survival gear frames it all in another way. In her book, Mommyblogs and the Changing Face of Motherhood, May Friedman writes against criticisms that mommy blogs will cause harm to the children who later in life encounter their own childhoods documented online. She writes:

There has been a lot of criticism thrown at my generation, and those younger, for oversharing, for selfies, for self-absorption, and toward mothers in particular for conspicuously mothering on social media. (This is a criticism I was responding to when I resisted baby photos on Facebook so many years ago). But the idea of survival gear frames it all in another way. In her book, Mommyblogs and the Changing Face of Motherhood, May Friedman writes against criticisms that mommy blogs will cause harm to the children who later in life encounter their own childhoods documented online. She writes:

Children are silent witnesses to their own parenting, unable to recall the nuances of their own infancy and early childhood. Indeed, it is arguable that children can only remember parenting as it becomes combative. By reading not only about their mothers’ struggles, but also about their mothers’ obvious love and care, perhaps adult children may find their relationships with their mothers bolstered rather than damaged. Whether the outcomes are positive or negative, mommyblogs allow children to see their mothers as three-dimensional individuals…

This morning when I read of the sudden death of Today’s Parent editor Tracy Chappell, I thought about her post from December, “Why I’m breaking up with my blog,” which is one of the most thoughtful pieces on blogging I have ever encountered. I’m going to be using it in my course going forward. She writes about blogging makes you live your life in a more reflective way, see the world differently, and how blogs are such remarkable records of these lives we live.

This morning when I read of the sudden death of Today’s Parent editor Tracy Chappell, I thought about her post from December, “Why I’m breaking up with my blog,” which is one of the most thoughtful pieces on blogging I have ever encountered. I’m going to be using it in my course going forward. She writes about blogging makes you live your life in a more reflective way, see the world differently, and how blogs are such remarkable records of these lives we live.

Chappell writes, similarly to Friedman:

I hope that, through this blog, they will learn to see me as not just “Mom” but as a woman who had her own things going on—a career, relationships, dreams, struggles, goals—as I was wiping bums and making dinner and gently (oh-so-gently) brushing knots out of hair. I hope they’ll see the value in taking lots of pictures and marking special moments. I hope they’ll understand that parenting is really hard and also has great rewards. I hope they’ll see how much fun we had. I hope they’ll see that I recognized and appreciated their many beautiful, individual gifts, even if they thought I wasn’t paying enough attention at the time. I hope they’ll see how hard I tried. I hope they’ll see how much they were loved. I hope they’ll see how proud I’ve always been to be their mom.

These would be poignant words anyway, but mean so much more now with their writer’s death. What a legacy for her girls, all those posts, which will provide them answers to those questions all of us have about our childhoods, answers that are forever lost to time, confusion, blurry brains. How they will still have this remarkable access to their mother’s voice, even now that she is gone. It will never make up for their loss, but what a gift too, to be able to know who she was. And how profound her love was for them.

All of which underlines my sense that these acts of documentation are some of the most important things we’ll ever do.

May 5, 2015

Motherhood and Creativity: In Conversation with Rachel Power

Everything is a circle. I first learned about Rachel Power’s work through serendipity and (what else?) blogging and talking about books. In 2008, the Australian writer and artist left a comment on my blog about the ambiguous ending to Emily Perkins’ Novel About My Wife, and I discovered her blog and her book, The Divided Heart.

Everything is a circle. I first learned about Rachel Power’s work through serendipity and (what else?) blogging and talking about books. In 2008, the Australian writer and artist left a comment on my blog about the ambiguous ending to Emily Perkins’ Novel About My Wife, and I discovered her blog and her book, The Divided Heart.

At the time, I was pregnant with my first child and so still very much on the periphery of “the motherhood conversations” of which I’d be privy to in the months to come. And so The Divided Heart was my first hint of these, where I first read about maternal ambivalence, the struggle (emotional and practical) for mothers to assert their creative selves, and the myriad ways women find to make it work. It was a hugely important book for me. I read it before I read Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work!

And because everything is a circle, The Divided Heart is now back in print as Motherhood and Creativity: The Divided Heart, and where Power left a comment on an interview I’d done seven years ago, I’m now interviewing her—about the book, how it’s changed in its new edition, the ways in which the motherhood conversation has changed since 2008, and how motherhood can connect us to our creative selves and to the world.

****

Kerry: The Divided Heart was one of my foundational texts on motherhood and mothering—I read it while I was pregnant in 2008. Which seems like a lifetime ago now, but I am so pleased that it has found new life as Creativity and Motherhood. The book played a huge role in my own experience of my heart actually not being so divided when it came to motherhood and creativity—you showed examples of how women combine the two, even when the balance is tricky. These women showed me what was possible. So I really like the new title—but how did the title change come about?

Rachel Power: Thank you for those generous comments about the book. It’s very flattering that someone as well-read as you would consider my book any kind of “foundational text”! I know your book has become the same for so many women out there.

With this new edition, called Motherhood & Creativity, the publishers had some radical changes in mind for the title, which I have to admit I largely resisted. I actually pushed pretty hard to keep “The Divided Heart” in there (it became the subtitle), because I still believe it represents the central drama of the experience for many if not most creative people with children: the desire to be in two places at once; the fear that being properly dedicated to one role inevitably risks neglecting the other. For me, those words introduce the initial question the book is trying to address. But as you say, that doesn’t mean it is full of women who are bogged down by those feelings; rather, it’s full of examples of artists who’ve found ways to forge ahead despite, and sometimes because of, those dilemmas.

With this new edition, called Motherhood & Creativity, the publishers had some radical changes in mind for the title, which I have to admit I largely resisted. I actually pushed pretty hard to keep “The Divided Heart” in there (it became the subtitle), because I still believe it represents the central drama of the experience for many if not most creative people with children: the desire to be in two places at once; the fear that being properly dedicated to one role inevitably risks neglecting the other. For me, those words introduce the initial question the book is trying to address. But as you say, that doesn’t mean it is full of women who are bogged down by those feelings; rather, it’s full of examples of artists who’ve found ways to forge ahead despite, and sometimes because of, those dilemmas.

As for using the word “creativity” instead of “art” (the original subtitle was “Art and Motherhood”), this felt like a necessary recognition that creativity is an important part of many people’s lives, expressed in different ways, but that doesn’t mean they all identify as “capital-A” artists. That’s why I really wanted craft-maker and blogger Pip Lincolne in this new edition: she has such a strong creative drive—and such a creative approach to life!—but I don’t think she would identify as an artist, as such. I knew that many readers would relate to that.

Kerry: It’s a very different book for me now—not just in title. I’m much more experienced in both motherhood and being creative than I was in 2008, and I relate to different parts of the conversations. How has the book changed for you? Was revisiting it a welcome experience?

Rachel: Like you, of course, I’m much further along in my parenting (my kids are 13 and 10 years old now!), but the issues remain very current to me, so I found it easy to slip back into the mothering and art conversation for the new edition. The demands are different, but just as intense, I find. With my son starting high school this year, I feel like I’m going back to school myself—my weekends have been almost completely hijacked by helping him with his homework!

But one of the main realizations for me, as someone who works full time, is that holding down a day job has been a much greater barrier to creativity than mothering. In the first edition, writer Anna Maria Dell’Oso said that when she was at home with small children she felt much closer to “the centre of her integrity” than when she was at the office, and I totally relate to that now. Finding time for art is a big challenge when your kids are small, but the upside is that in some fundamental way, we are already in a very creative space as parents, even though it’s hard to recognize that at the time.

“Finding time for art is a big challenge when your kids are small, but the upside is that in some fundamental way, we are already in a very creative space as parents, even though it’s hard to recognize that at the time.”

Kerry: What about the book’s actual changes? What else is different in this new edition?

Rachel: The new edition contains around half of the interviews from the former book and the same number again of new interviews. Much like the first time around, I approached women I admire, and was lucky enough to interview one of Australia’s best-loved actors Claudia Karvan; visual artists Del Kathryn Barton and Lily Mae Martin; writers Cate Kennedy, Tara June Winch and Lisa Gorton; musicians Holly Throsby and Deline Briscoe; and craft maker and blogger Pip Lincolne.

The other coup this time around was adding a preface from musician Clare Bowditch, who as an old friend and neighbour of mine, not only witnessed the genesis of this book, but also shared in the early years of child-rearing with me. So apart from my own family, there is really no-one closer to this book than Clare, and her preface is affirming and moving and humbling all at once. I’m very grateful for it.

My introduction and conclusions in the first issue are heavily truncated into one opening chapter in the new book. I had done a lot of research before writing the first edition and basically presented my poor editor with a 140,000-word thesis! This was cut back heavily, obviously, but the new publishers felt that it was still a bit too academic in style. So the new intro is a bit less wordy and hopefully more accessible as a result.

Image by Launch Bubble

Kerry: How did the new edition come to be? What were the signs that the demand for it was out there?

Rachel: The Divided Heart went out of print a while ago, and it was really upsetting me that people couldn’t get their hands on a copy. I was still getting lots of letters and emails from potential readers asking where they could find books, but I only had one copy myself! So it was very exciting to find a new publisher in Affirm Press. Initially, it was just going to be a shortened version of the original. But as we went forward, editor Aviva Tuffield and I decided that it would be good to create a different book, to bring it up to date, and so there was new value for those who already had the original edition.

Kerry: Are you finding the reception different this time around? My sense is that we’re living in a slightly different climate now in regards to talking about motherhood—there is more space for nuance. Though this might be because I’m now in that climate instead of looking on. What do you think?

Rachel: That’s an interesting observation! I think there is definitely more space for nuance in the feminist debate generally, and that we have largely moved on from the dispiriting “mummy-wars” that were dominating the conversation around the time I first published The Divided Heart. Motherhood has definitely taken centre-stage in a way it hadn’t when I had my first child, and so there seems to be less division between the different parts of people’s lives nowadays—and between those who have kids and those who don’t—which can only be a good shift for society, I think. That said, most of the criticisms I’m receiving this time around are the same as last time: chiefly, that this is a bunch of middle-class women indulging their hobbies and complaining about their kids (which is such a tedious misrepresentation of the actual stories it contains).

From the outset, part of what interested me in the subject of artist-mothers was that I saw the unique contribution it could make to the feminist debate, precisely because it is a nuanced issue—both in terms of work/economics and of family/housework. Writer Alice Robinson summed it up beautifully in her recent piece for Overland journal, when she said that “as a stay-at-home parent by day, a writer by night, I am doing what untold numbers of people in each camp, and all those in both, are doing: two challenging but largely unpaid jobs. … each undervalued in the remunerative sense, but fundamental in the cultural.”

“To have a child is to enter into a strange new set of negotiations with society, our partners, our family, ourselves. To also be an artist, it seems to me, is to be dealing with the extreme end of those negotiations.”

Image by Lily Mae Martin

To have a child is to enter into a strange new set of negotiations with society, our partners, our family, ourselves. To also be an artist, it seems to me, is to be dealing with the extreme end of those negotiations, because of the self-driven nature of art and the lack of guaranteed compensation. At a personal level, asserting your need to create; to carve out the time and space that art demands; to feel confident in the validity of what you have to say–requires a special kind of drive and determination for anyone. Doubly so for mothers, whose own interests and desires are expected to be sublimated to the needs of others.

So, in my mind, endeavouring to be both artist and mother raises some of the biggest questions about how we choose to live and view the world: self versus society, partnering versus independence, feminism versus masculine, sacrifice versus self-interest, creativity versus economics… In this way, I think the experience of artist-mothers can speak to the feminist debate at a particularly subtle and sensitive level.

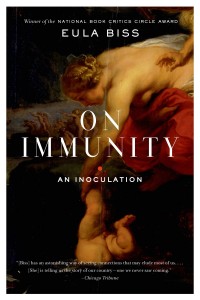

Kerry: Motherhood is so incredibly interesting, the ideas around it far-reaching and important. I’m thinking about the book On Immunity by Eula Biss, a vast and important sociological text, and in her acknowledgements, she thanks the mothers in her community who made her realize “how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are…”

Kerry: Motherhood is so incredibly interesting, the ideas around it far-reaching and important. I’m thinking about the book On Immunity by Eula Biss, a vast and important sociological text, and in her acknowledgements, she thanks the mothers in her community who made her realize “how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are…”

I didn’t really understand this when I first read your book, when I first became a mother—the ramifications of the ideas you’re talking about, we’re all talking about. (I certainly had no idea that motherhood would be so interesting that I’d end up editing an anthology about it too years later….)

Another interesting thing is that it’s ever in flux. What are the questions and ideas around motherhood that are preoccupying you these days?

Rachel: As you say, mothers are raising the next generation, so their actions and decisions are far-reaching and important indeed! Mothers have a unique stake in the future, and that’s why they are spearheading so many campaigns and movements around the world. In Motherhood & Creativity, writer Tara June Winch, who herself set up onethousand.org (a charity to promote female empowerment), says, “I’ll argue that most NGOs, globally are run by mothers in one way or another.”

Motherhood is a galvanising force—and one of the best things about writing The Divided Heart was that it connected me to an incredible community of mothers, who think very deeply about the way they parent but also about the world that they have brought their children into. Fathers are there too, of course. But among the families I know, while fathers are very much involved, it’s largely mothers who are still doing much of the logistical work as well as the theoretical thinking behind the parenting—and most of the worrying, sadly!

Motherhood is a galvanising force—and one of the best things about writing The Divided Heart was that it connected me to an incredible community of mothers, who think very deeply about the way they parent but also about the world that they have brought their children into. Fathers are there too, of course. But among the families I know, while fathers are very much involved, it’s largely mothers who are still doing much of the logistical work as well as the theoretical thinking behind the parenting—and most of the worrying, sadly!

Personally I have always found mothering hugely confronting; the role presses me to be a stronger, braver, more industrious person than I feel capable of being most days. And we are raising kids in unusually complex times. I’m very conscious of wanting to raise children who feel empowered in a culture that is: 1) largely driven by a consumer-capitalist ethos; and 2) facing potential catastrophe as a result. The big question for me is: how do we raise kids who are critical and creative thinkers, who will make ethical decisions, and who will treat the environment, themselves and other people with respect, when right now all they want is a PlayStation 4 for Christmas?!

I think creativity can play a big role in all of this. I love Pip Lincolne’s comment in the book: “There’s a forgiving, nurturing quality about handmade that should be applied to life. Not everything is perfect, but it was made with good intentions and there were so many little, meaningful decisions along the way. I think that mindful approach is such a good thing and an ace ethos for a family.”

Could there be a better approach to bringing up kids? I reckon Pip has it pretty sorted!

April 9, 2015

Motherhood Milestones

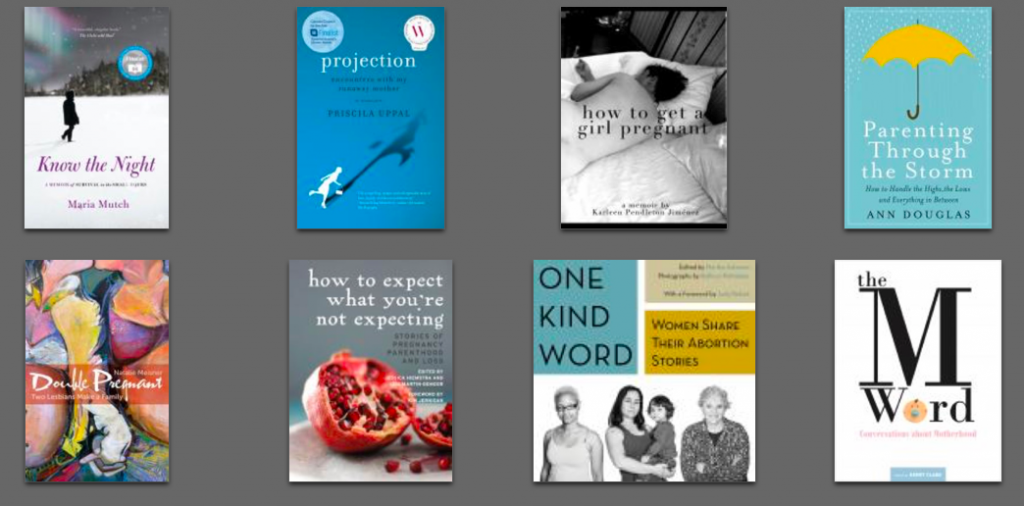

The M Word was published nearly a year ago, and Mother’s Day is just about a month away. To mark both these milestones, I’ve made a list of Canadian non-fiction books that have been expanding the conversation about motherhood along with The M Word.

April 6, 2015

Departures and Arrivals

We leave for our trip this week, and I keep waiting for that lull between our departure and the time in which nobody in our family is sick, but the window for such a thing is disappearing, and I am so very tired. And sick, again. There was about five minutes on Friday when I wasn’t, and then cold symptoms returned on Saturday morning shortly after my child threw up in a shoe store, which was a brand new milestone for all of us. But nevertheless, Easter was had, a holiday we celebrate for its pagan roots and not the Jesus bits. We’re all about the eggs, and the new life that comes with spring—I met a baby today who turns two weeks old tomorrow, and she was a miracle unfolding. We had a lovely visit with my parents, and saw friends on other days, and Harriet and Iris got the new Annie movie on DVD, and Harriet has watched it five times already. There are crocuses across the street. We are assembling our playlist, a CD of driving tunes for the journey from Berkshire to Lancashire (which I’m the smallest bit nervous about, Iris having just now decided that she hates cars. “Car, no. Car, no.”)

We leave for our trip this week, and I keep waiting for that lull between our departure and the time in which nobody in our family is sick, but the window for such a thing is disappearing, and I am so very tired. And sick, again. There was about five minutes on Friday when I wasn’t, and then cold symptoms returned on Saturday morning shortly after my child threw up in a shoe store, which was a brand new milestone for all of us. But nevertheless, Easter was had, a holiday we celebrate for its pagan roots and not the Jesus bits. We’re all about the eggs, and the new life that comes with spring—I met a baby today who turns two weeks old tomorrow, and she was a miracle unfolding. We had a lovely visit with my parents, and saw friends on other days, and Harriet and Iris got the new Annie movie on DVD, and Harriet has watched it five times already. There are crocuses across the street. We are assembling our playlist, a CD of driving tunes for the journey from Berkshire to Lancashire (which I’m the smallest bit nervous about, Iris having just now decided that she hates cars. “Car, no. Car, no.”)

Tonight we’re watching the new Mad Men, which premiered last night, but we watch it on download from iTunes so are behind the people who watch it on TV. I don’t know what I’m going to do in a world without Mad Men, a show that has been such a huge part of my life for years now and which has seriously informed my reading life too. It’s a good time to re-share The Canadian Mad Men Reading List, which I made last year, and am seriously proud of. Oh, Stacey MacAindra. Maybe I’ll finally get around to finishing The Collected Stories of John Cheever. I still haven’t read “The Swimmer.” I’ve been saving it, I think, of the post-Mad Men world. In which I am probably going to go right back to Season One.

Tonight we’re watching the new Mad Men, which premiered last night, but we watch it on download from iTunes so are behind the people who watch it on TV. I don’t know what I’m going to do in a world without Mad Men, a show that has been such a huge part of my life for years now and which has seriously informed my reading life too. It’s a good time to re-share The Canadian Mad Men Reading List, which I made last year, and am seriously proud of. Oh, Stacey MacAindra. Maybe I’ll finally get around to finishing The Collected Stories of John Cheever. I still haven’t read “The Swimmer.” I’ve been saving it, I think, of the post-Mad Men world. In which I am probably going to go right back to Season One.

Today I found a poem about motherhood, bpNichol Lane, Coach House Books and Huron Playschool, written by Chantel Lavoie for the Brick Books Celebrating Canadian Poetry Project. I find myself struck by the poem and the various ways it connects with my life, and how literature and motherhood and the fabric of the city are all so enmeshed. Particularly in this neighbourhood.

And finally, I am in a peculiar situation book-wise. I don’t know what books to take with me on vacation. Now, on a certain level, bringing any books on vacation is simply stupid because all I ever do when we go to England is buy books. And when I look at my to-be-read shelf now, no contenders jump out on me—nothing good for an airplane, nothing I am truly destined to love, no book with which I’d be thrilled to be holed up with in an airport terminal. You can’t take chances in a situation like this! So I have decided…to bring no books with me. This is truly the wildest and craziest thing I’ve ever done. This year, at least… To pick up a book at the airport, and trust I’ll find the right one there, and then live book to book. No safety net. This is terrifying. And yet potentially exhilarating, rich with adventure. The book nerd’s equivalent of jumping out of the sky.

April 1, 2015

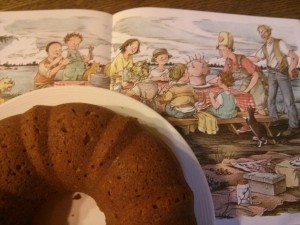

Mrs. Peter’s Birthday Cake

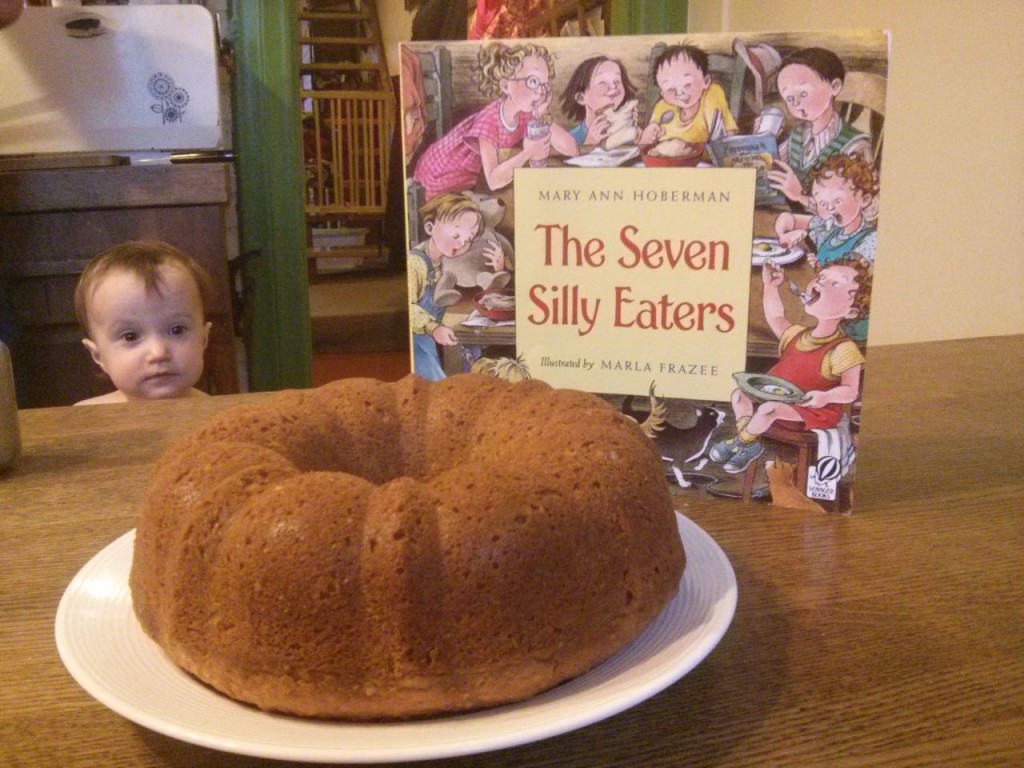

I’m about as crazy about literary cakes as I am about books illustrated by Marla Frazee (and written by Mary Ann Hoberman, no less), so I’ve been meaning to write about The Seven Silly Eaters for quite some time. A book that I’m actually ambivalent about, even though it has rhyming couplets. It’s down the other end of the spectrum from Mem Fox’s Harriet, You’ll Drive Me Wild, another book illustrated by Frazee. Harriet is the story of a mom who reaches her breaking point after being sorely tested, and she finally explodes at her extremely irritating (albeit loveable) daughter, and then apologizes and everything is okay. Because mothers are human. Getting angry and upset is what people do, and I think there’s nothing wrong with mothers modelling this. Imagine the child who’s gone through his entire life without learning the fact that people get upset sometimes, that one’s behaviour can have consequences; what a rude awakening the actual world is sure to be.

But then there is Mrs. Peters who seems to never have heard of birth control (with seven children in as many years) or setting limits. One by one, each of her children conspires to destroy her person and her cello-playing dreams by making ridiculous culinary demands: her first child refuses his milk unless it’s warmed to a precise temperature; her second will only drink homemade pink lemonade; third would only eat freshly made applesauce; with the fourth it’s oatmeal, unless that oatmeal has the suggestion of a lump and then he dumps it on the cat; the fifth demands homemade bread; and the twins will only eat eggs, poached for one and fried for the other.

But then there is Mrs. Peters who seems to never have heard of birth control (with seven children in as many years) or setting limits. One by one, each of her children conspires to destroy her person and her cello-playing dreams by making ridiculous culinary demands: her first child refuses his milk unless it’s warmed to a precise temperature; her second will only drink homemade pink lemonade; third would only eat freshly made applesauce; with the fourth it’s oatmeal, unless that oatmeal has the suggestion of a lump and then he dumps it on the cat; the fifth demands homemade bread; and the twins will only eat eggs, poached for one and fried for the other.

And while Mrs. Peters is happy in her bubble of domestic chaos—this is certainly the life she chose and she likes the pace—the resentment does eventually seep in. Not overwhelmingly, and she seems to accept it the way she’s accepted everything. “What a foolish group of eaters/ Are my precious little Peters,” she muses as she strains the oatmeal for the 4000th time. She thinks they’ve forgotten her birthday, and then she goes to bed sad—has there ever been anything more pitiful than that?

She should have put a stop to the whole thing years ago. “Make your own fucking applesauce, Little Jack. I’ve got a cello to play.” Mothers are people. It’s a good thing for a child to know.

But! Here is the twist. The children have not forgotten their mother’s birthday. Instead, they’ve crept downstairs in the middle of the night to make their mother all their most beloved foods—and do note that they don’t think to make her favourite food. It is quite possible that they’ve never considered that she has one. And because she gave them all a fish instead of teaching them all to fish, proverbially speaking, they have no idea how to cook anything, and so they abandon the project in the middle of it all, their dubious concoctions dumped in a pot and stuffed in the oven.

But! Here is the twist. The children have not forgotten their mother’s birthday. Instead, they’ve crept downstairs in the middle of the night to make their mother all their most beloved foods—and do note that they don’t think to make her favourite food. It is quite possible that they’ve never considered that she has one. And because she gave them all a fish instead of teaching them all to fish, proverbially speaking, they have no idea how to cook anything, and so they abandon the project in the middle of it all, their dubious concoctions dumped in a pot and stuffed in the oven.

Where Mrs. Peters discovers it in the morning: miraculously, a pink and plump and perfect cake!

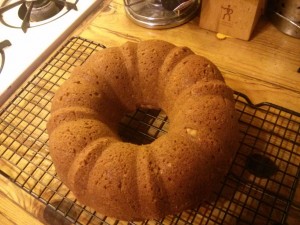

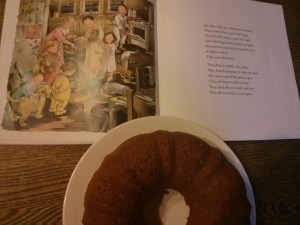

Naturally, we wanted to make it. The Seven Silly Eaters is a book that was born to have a recipe at the end, but there is none. Sadly. And we’re not the only people who thought so (google it: the Internet is rife with parent bloggers making Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake)—due to such a huge demand, Mary Ann Hoberman herself came up with a Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake recipe! So we made it too. Though I thought it was cheating because lemon juice in the milk (to create buttermilk) isn’t really pink lemonade, and she pinks the cake with red food colouring. So I decided to add lemon zest to the cake to make the lemon more authentic, and had the clever idea to make it pink by adding pureed beets to the applesauce (which isn’t in the recipe at all—perhaps Mrs. Peters went on to have a beetroot-loving eighth child?). My clever idea fizzled out, however, because by the time the cake was done, all the pinkness appeared to have been baked out of it. Alas. But the cake was totally delicious. Maybe not delicious enough to make up for more than seven years of domestic tyranny, but I was not asking such things from it.

Naturally, we wanted to make it. The Seven Silly Eaters is a book that was born to have a recipe at the end, but there is none. Sadly. And we’re not the only people who thought so (google it: the Internet is rife with parent bloggers making Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake)—due to such a huge demand, Mary Ann Hoberman herself came up with a Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake recipe! So we made it too. Though I thought it was cheating because lemon juice in the milk (to create buttermilk) isn’t really pink lemonade, and she pinks the cake with red food colouring. So I decided to add lemon zest to the cake to make the lemon more authentic, and had the clever idea to make it pink by adding pureed beets to the applesauce (which isn’t in the recipe at all—perhaps Mrs. Peters went on to have a beetroot-loving eighth child?). My clever idea fizzled out, however, because by the time the cake was done, all the pinkness appeared to have been baked out of it. Alas. But the cake was totally delicious. Maybe not delicious enough to make up for more than seven years of domestic tyranny, but I was not asking such things from it.

We love this book. I hope I haven’t suggested otherwise. Frazee’s illustrations are so chock full of detail that they can be explored for ages, and there are all kinds of extra-textual stories going on in the background. The family dynamic is fascinating to consider, and perhaps it’s a good discussion point for children—what happens when a family allows its mother to be treated this way? It’s a call for everyone to do her share. It’s a plea for less ridiculousness when it comes to the demands of picky-eaters. But mostly, it’s a cautionary tale for mothers, I like to think. To have limits and live inside them, to not give and give until you have nothing left for yourself. To admit that you too are a person whose needs must be met, and therein lies the negotiation of family life—a useful education for any child.

We love this book. I hope I haven’t suggested otherwise. Frazee’s illustrations are so chock full of detail that they can be explored for ages, and there are all kinds of extra-textual stories going on in the background. The family dynamic is fascinating to consider, and perhaps it’s a good discussion point for children—what happens when a family allows its mother to be treated this way? It’s a call for everyone to do her share. It’s a plea for less ridiculousness when it comes to the demands of picky-eaters. But mostly, it’s a cautionary tale for mothers, I like to think. To have limits and live inside them, to not give and give until you have nothing left for yourself. To admit that you too are a person whose needs must be met, and therein lies the negotiation of family life—a useful education for any child.

March 25, 2015

After Birth: Redux

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.