March 29, 2017

I love love love Workin’ Moms

Much like a certain recent US presidential candidate you may recall, the CBC television series Workin’ Moms is not a perfect candidate. There are some obligatory awkward Canadian production moments (Dan Ackroyd notwithstanding; his casting was brilliant); mild implausibility (how do the workin’ moms manage to fit a mommy’s group into their workdays?); and wardrobe decisions I didn’t blink at but that drove my actual workin’ mom friends berserk—apparently sleeves in the office are pretty much de riguere? Who knew. But over the first season of the show it’s become clear to me that perfection was never what the shows creators were striving for. They put a wandering kodiak bear in the pilot, for heaven’s sake. And it was that bear, or rather character Kate’s response to it, that had me hooked, her serious, furious primal scream. In that powerful moment we were witnessing a mother being born.

The show’s frequent comparisons to HBO’s Girls are not amiss in that neither is a series about women in general, which keeps tripping viewers up “because we’re still more comfortable seeing women as universal types rather than distinct individuals.” If women in general get this treatment, then mothers get it doubly, and the creators of Workin’ Moms are actively working against those expectations of who mothers are and what they should be. In fact, they’re working against all expectations, hence the kodiak bear.

From the start, here is what I loved about the series: first, that the characters aren’t foils. They’re people. That they aren’t having existential crises about matters most people really do manage to work out in reality if not on TV—like, “Oh my god, can I be a mom AND a person?” “Is it okay that I really like my job more than I like taking care of my baby?” “Is it simply inexcusable to admit that I find devoting my entire self to motherhood is more than a bit unfulfilling?” I mean, these are questions the characters in the show are working through, but it’s the process that matters—it’s not as though entire plot points hang upon them. I also like that the workin’ moms’ partners (who are dads, but for one exception) are generally decent human beings. Making dads look dumb is really stupid comedy, and this show is much too smart for that.

I knew I loved the show in the first episode when Frankie started fantasizing about being hit by a bus. She doesn’t want to die, she explains, but how she’d love to go into a coma for eight weeks or so. Later we see her with her head stuck under water in the house she’s showing for a sale. Soon after, she kinda sorta slips under water in the bathtub with her baby daughter—only just caught by her partner. She’s fallen asleep, she claims. A tiny slip. Enough to make the viewer very uncomfortable, which the series never fears to do.

Another character whose trajectory messed me up was Jenny, who headed back to her IT job reluctantly while her husband embraced his time as a stay-at-home dad, and thereby became completely unappealing to her, sexually and otherwise. She starts having weird fantasies about her nerdy manager, and leaving provocative messages on his Facebook page. Alienated from her roles as mother and wife, she starts acting out in outlandish ways, most memorably on the girls’ night out when she demands someone pierce her nipple, which squirts milk at the moment of laceration. Predictably, the nipple gets infected.

I loved Anne, who’s struggling with her older daughter (oh my gosh, when she starts wondering if there’s a slut gene and she’s passed it onto her) and a young baby when she realizes she’s pregnant again. This accidental pregnancy does not come as good news, and she struggles with facing it in her characteristically blunt style—”You’re angrier than usual, Anne,” the leader of the mommies group remarks to her. The group in general in general is a bit put off by the fact that Anne keeps bringing up that she’s considering an abortion. Which is kind of sacrilege in a room full of babies.

And then yes, the abortion. It’s long been a complaint of mine not just that abortions aren’t shown on TV very often, but particularly that nobody ever gets to make jokes about them. (I actually have a long term aspiration to become an abortion humorist.) Workin’ Moms going against the grain again as Anne’s friend Kate (who’s played by show creator Catherine Reitman) cracks this one as she’s driving Anne to a clinic and they’re considering whether you’d Yelp an abortion clinic based on ratings or proximity. Ratings, definitely, Kate figures, and then she takes it further: “I wonder what kinds of complaints an abortion clinic gets? One star. Still pregnant.”

And Kate, my favourite. All life in the city—she’s glorying in the beauty of the day in the park with her son as a vagrants’ pissing against a tree. Sardonic, bad-assed and unapologetic—particularly about her lack of sleeves. Her story throughout the series involves her return to work at a PR firm where she’s firmly established as successful, but she finds she has to redefine her professional role at work now that she’s a mother. Further, she’s a candidate for a prestigious position in Montreal, which would involve leaving her husband and son for three months. Is this something she’s willing to partake in for professional success? (Spoiler: in Tuesday’s episode we see her glorying in her clean white bed, alone, a full night’s sleep, and not a single soul to breastfeed. As any mother knows, there’s not drug in the world as incredible as solitude—but it’s also possible to get too much of a good thing.)

At the beginning of the show in January, Workin’ Moms received a terrible review from John Doyle in the Globe and Mail who chastised the show for its characters’ entitlement. “Oddly, to me, Workin’ Moms celebrates what was mocked with deft scorn by the Baroness Von Sketch series and the Canadian comedy Sunnyside. So, whose side are we supposed to be on? If it’s these appallingly smug people, heaven help us all.” But what the review only proves is that John Doyle doesn’t get it—it’s never been about sides. And what’s remarkable about Baroness Von Sketch and Workin’ Moms alike is that nobody is pitted against no one. Not unless, of course, there’s a very good reason…

In her celebration of Baroness Von Sketch, Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer writes of how the show “celebrates and spoofs the mundane realities in which modern, urban women find themselves depicted. And oh, how the Baronesses know the contours of the boxes in which we live. They have it mapped out like diligent and transgressive draughtswomen who, instead of yielding to the airtight edges of their inherited designs, work to erase them.” And I would argue that Workin’ Moms is a similar kind of project. More subtly though—this isn’t sketch comedy after all. And because it isn’t, the show has to develop in-depth female characters with sustained narratives, and some people hate that. Remember that flawed candidate I started this post with?

Workin’ Moms isn’t perfect, but it never wanted to be—which is the reason it manages to be transgressive, hilarious and discomforting all at once. And it doesn’t fucking care if you don’t like it, which is why I loved it.

The series finale airs next week, but you can watch the whole thing online.

January 19, 2017

I don’t want to tell them, “Nothing.”

“One day my daughters will ask what I did to save the world for them, and I don’t want to tell them, ‘Nothing.’” I wrote a piece for Today’s Parent about why I’m taking my daughters to the Women’s March here in Toronto on Saturday.

See you there, or in solidarity?

December 13, 2016

Awkward Conversations

As a parent, having uncomfortable conversations with my daughter is one of my favourite things. The other day after listening to the news on the radio, she asked me, “What’s sexual assault?” And I was so grateful to be able to answer that. To be able to give her the context for these awful, disturbing ideas, rather than her getting her context from elsewhere, from less reliable sources. From the cruel world even, when she’s utterly unprepared for it. It’s the same reason I read her the Grimms with the violent endings, the nasty stepmother destined to dance eternally in shoes made of burning iron. Even though these deliverances of justice aren’t in keeping with reality, I think the fact that the world can be brutal and hard. I don’t want these things to ever come as a surprise to her. I willingly brought my daughter into the world, and along with that, I see myself as required to take responsibility for all of it, the good and the bad.

They aren’t opposing, also, the good and the bad. This is what I want to teach my daughter about the world, about its complexity “A single thing can have two realities,” is a line I wrote in my essay, “Doubleness Clarifies,” about motherhood and abortion. It’s always been a lesson I wanted her to learn. “And so one day I will tell her about what happened to me a long time ago,” I wrote about my daughter and my abortion, in this essay I wrote when my daughter was three. I was always grateful for that essay, because it meant I’d never be able to not tell her what happened to me. It would force me to take responsibility too for this part of my own story.

Last week I shared the above photo of protesters from the 1970 Abortion Caravan in Ottawa on Instagram. I spend a lot of time on Twitter raging about abortion access and perception, while my Instagram feed is all teacups in soft sunshine. I wanted to be more well-rounded in my Insta-life, so I shared the image. And later that night, Harriet was scrolling through my feed and saw the photo. “Who are they?” she asked, and so I told her about abortion.

I told her about the brave women (and men) who fought hard so that she and I could have control over our reproductive lives. I told her about how people are trying themselves in knots trying to restrict women from aborting lentil-sized fetuses. “But it’s not their lentil,” she said. “I KNOW!” I answered. And I told that when she was a lentil, she was everything. We read her stories even though she didn’t even have ears. But she was everything because we loved her already and we wanted her. In physical terms, she was almost nothing. Pregnancy is perilous at 6 weeks.

I told her about my friends who’ve had abortions later on, when everything is so much harder. About how these were heartbreaking choices, the losses of children who were desperately wanted. About how nobody has an abortion for fun. It’s always a careful choice, and sometimes not an easy one. And it’s hard to understand because one person’s lentil is someone else’s baby. But Harriet is seven and already she understands that a single thing can have two realities.

I haven’t told her yet that I had an abortion. She didn’t ask. These conversations have to be organic, I think. But I’m sure I’ll tell her soon, and when I do I’ll tell her this: “If not for my abortion, I wouldn’t have YOU, and I’m grateful everyday.”

December 1, 2016

Swimming Lessons: Addendum

Full disclosure necessitates I update you on how things have proceeded since I read about exiting Guardian Swim and the beginning of my new career reading on the poolside. I thought I was being so clever this time, not keeping my child in Guardian Swim until she was five, which was what happened last time. Never again was I going to have my school-age child in the same swimming class as an infant, and so Iris was enrolled in Sea Turtle. This time we were going to do it right, and it was so right, for the first two lessons, at least. Iris is part mermaid and was happily floating on her back, and she had the most excellent swimming instructor in the entire history of our life in recreational programs…and then, for absolutely no reason, when we arrived at class for Week 3, Iris refused to get into the pool. And there we’ve been ever since, Iris screaming whenever forced to come into contact with the water, turning her body into a plank or a noodle, whichever would prove most inconvenient. And when you’re a parent who’s been expecting to spent 30 minutes reading poolside, the prospect of a screaming kid refusing to enter the pool is most frustrating. There was swearing.

Full disclosure necessitates I update you on how things have proceeded since I read about exiting Guardian Swim and the beginning of my new career reading on the poolside. I thought I was being so clever this time, not keeping my child in Guardian Swim until she was five, which was what happened last time. Never again was I going to have my school-age child in the same swimming class as an infant, and so Iris was enrolled in Sea Turtle. This time we were going to do it right, and it was so right, for the first two lessons, at least. Iris is part mermaid and was happily floating on her back, and she had the most excellent swimming instructor in the entire history of our life in recreational programs…and then, for absolutely no reason, when we arrived at class for Week 3, Iris refused to get into the pool. And there we’ve been ever since, Iris screaming whenever forced to come into contact with the water, turning her body into a plank or a noodle, whichever would prove most inconvenient. And when you’re a parent who’s been expecting to spent 30 minutes reading poolside, the prospect of a screaming kid refusing to enter the pool is most frustrating. There was swearing.

Last week was the second last class, and there was finally progress. Iris got in the pool, but in order for this to happen I had to be crouching at the pool’s edge, basically sitting in a puddle and being splashed whenever anyone practiced kicking. There was no reading.

All of which is to say that this underlines my growing suspicion that there is really no way to do parenthood right. No matter how you swing things, they’re probably always going to be a bit annoying.

October 4, 2016

Goodbye, Guardian Swim.

When Harriet was a baby, we had no money but plenty of time, and so instead of enrolling her in swimming lessons as the swishy pool near our house (with salt water and everything!) I signed up for cheap swimming lessons at the city-run pool that was far away and at the top of the only hill in this entire city. It was better than joining a gym, I decided, and only cost $33 dollars, and so began my Guardian Swim years, which is the more inclusive name for the Parent and Tot program I remember from my own childhood.

When Harriet was a baby, we had no money but plenty of time, and so instead of enrolling her in swimming lessons as the swishy pool near our house (with salt water and everything!) I signed up for cheap swimming lessons at the city-run pool that was far away and at the top of the only hill in this entire city. It was better than joining a gym, I decided, and only cost $33 dollars, and so began my Guardian Swim years, which is the more inclusive name for the Parent and Tot program I remember from my own childhood.

In the beginning, I was very excited. In the beginning, I find, parents need to strive in order to enact parenthood properly (luckily, many of us outgrow this compulsion) and guardian swim was one way to do so. It was also something to do with my baby that didn’t involve me lying on the carpet being bored out of my mind. It got us out of the house. (The idea that there was a time in my life when I was desperate for excuses to “get out of the house” distresses me now. That sounds awful. I never want to be that person ever ever again.) I am sure I found the first lesson exhilarating. Fortunately, I was never that poor parent whose baby screamed throughout the entire lesson every week and eventually we had to give up going swimming altogether, $33 dollars sadly to waste. Harriet liked the water, I liked having something to do, and so we did it, session after session. I have done “The Fish Wishy” so many times.

Oh, Guardian Swim. Once in a while I signed up for you, and the first class would have this terrific, dynamic teacher with lots of games, songs and ideas, and every time we met that teacher, she or he taught the one class and we never saw them again. Most of the other instructors had a short repertoire, and then would grant the class “free time,” and my baby and I would flounder aimlessly in the pool watching the clock until it was time to go home. There would be plastic toys, and the children would be drawn to them, but once the baby had a toy boat in hand, there wouldn’t be so much to do.

My most favourite part of Guardian Swim was when my husband took the baby into the pool, and I sat poolside reading a book. My least favourite part was when the instructor would give us an obligatory educational session, like how we shouldn’t leave our babies unattended by backyard pools or feed them marbles in case they choked. I also wasn’t big into the times that people pointed out that swim diapers contain faces but not urine, the thing that most of were trying really hard not to think about. There was the sessions with Shaheed, who was the worst teacher ever, and often would forget to come class, never mind that I’d climbed that hill and got my kid ready for it (and got out of the house even—no small feat) and when we got there and he wasn’t, they wouldn’t let us get in the pool. The seventeen-year-old lifeguard would shrug, no idea about my sacrifice—”Nothing I can do,” he’d say.

From Guardian Swim, I learned that I should get dressed before my child does, otherwise she will take her dry-clothed-self and sit right down in a puddle on the change room floor. I learned that she could play with my keys while I got changed, and be sufficiently entertained. She learned how to blow bubbles and how to kick her little legs. I learned not to feed her marbles. Nobody, however, ever learned to swim.

When Harriet was nearly four, she was still in Guardian Swim. I look back upon this with the confusion many parents do when they consider their experiences with their first child. Why were we still doing that? I think part of the problem was that she was terrified of us letting go of her in the water, and clung to me so hard it strangled. She wasn’t comfortable, and neither was I. I was waiting for something to happen, something to happen that would allow us to progress, but that something never arrived. The last time I signed Harriet up for Guardian Swim at the pool at the top of that great big hill, I was very pregnant, and I’d never considered the agony of pushing a stroller with a four-year-old up at that hill in such a condition. It was terrible. Harriet wasn’t learning anything, and there was a six-month-old baby in her class who had better technique than she had. Something was going to have to change.

When Iris was born, we were no longer broke. Not only could we afford the salt-water pool, but the convenience seemed worth every penny. Harriet began a swim program that wasn’t geared to infants, and it was Iris’s turn for Guardian Swim. Which I think she was enrolled in three times total. Because neither of us felt like getting in the pool, and it was always cold, and she always had a cold. I was tired of doing the fishy wishy.

When Iris was born, we were no longer broke. Not only could we afford the salt-water pool, but the convenience seemed worth every penny. Harriet began a swim program that wasn’t geared to infants, and it was Iris’s turn for Guardian Swim. Which I think she was enrolled in three times total. Because neither of us felt like getting in the pool, and it was always cold, and she always had a cold. I was tired of doing the fishy wishy.

We moved to the nearby university pool eventually (spoiled for pool choice, I know) because Harriet needed some help getting caught up and the shallow teaching pool gave her more confidence. The half hours we passed in that pool during Iris’s classes could possibly be scientifically proven to be the longest 30 minutes on record. Even though Iris could actually swim. Like, she was leaping out of our arms and we kept having to catch her before she sunk, and if we’d been daring enough not to bother, she might have floated after all.

By this point, we hated Guardian Swim. It was unfathomably boring. The other children were annoying. The teachers were children. Every week we’d go, and I’d cross my fingers for a pool fouling so we could go home early.

But finally, we have arrived. Last week Harriet began her first swim lesson in the “big pool” upstairs, and she was the first kid in her class to jump in the water (when once upon a time, she was vehemently opposed to such things, and I used to berate her about it, made her practice jumping off the bottom step of our staircase until she cried—not my finest moment as a parent, and it turns out her instructor was right when he suggested we leave her alone and she’d figure it out in time). And Iris started Sea Turtle, the first level post-Guardian Swim, and she was amazing, dunking her head and floating on her back, and these things that she would never have been brave enough to do had I been in the pool alongside her.

And me? I was where I’d always been waiting to be, cheering along poolside, content in the company of an excellent book. So happy with the progress, which is generally where I tend to be in terms of parenting, not looking back in sadness but just so happy to be moving on. Enjoying the ride. “Little girls get a little less little but instead of it feeling sad, it feels exhilarating,” writes Rebecca Woolf on the occasion of her daughter’s eighth birthday, and I love that idea.

Why not embrace the momentum, because it’s not going anywhere—but you are.

September 11, 2016

Ardent Desires

“Whom does a child belong to? What responsibility does it bear to those who ardently desired—or even designed—it without knowing what ‘it’ was?” —Rachel Cusk, “What She Bears.”

I always wanted to be a mother. It did not seem to be an idea worth examining, or it was worth examining as much as it’s worth examining why I might want to be a creature who walks upright or a being with lung capacity (although when I got pneumonia last winter, it was underlined how tremendously luxurious it is to be a person who breathes). My desire for motherhood was not something I’d been told I should want; it would have been impossible to talk me out of it. I read Rachel Cusk’s seminal book on motherhood, A Life’s Work, before I had a baby, and missed the point of it entirely, so intent was I upon upon my own desire to have a baby of my own, to make my own story. I suppose Cusk had been trying to warn me, even to talk me out of it, but I took no heed. I “ardently desired it” and I didn’t know what “it” was, it was true, but there are some boxes that don’t need to be unpacked. I do think that Rachel Cusk has made it her life’s work to make things far more complicated than they need to be.

Another thing I know is that there are women want to not be mothers as ardently as I wanted to be one. I am in complete understanding of that certainty. Those women and I are on the same wavelength, I’ve always thought. All of us wanting what we want because we’re listening to our own hearts, and not because this is what anyone has told us about how to be a woman.

—Ambivalence, by the way, is not the opposite of certainty. I think many of us manage to live with both. For example, I always wanted to be a mother. And then there was a time after I became one that I didn’t want to be a mother at all.—

It was during the time, after my daughter was born, when I didn’t want to be a mother and wondered how I’d got the whole thing so wrong, that I read Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work again, and finally understood what she writing about. And I was grateful that someone had been willing to write about what my days were like, the boredom, the desperation, the inanity of those people who were imploring you to “enjoy every minute.” That someone was writing about how motherhood was so terribly hard, and lonely. Putting a name to the thing, which was “maternal ambivalence.” Sometimes I hated my baby (usually in the middle of the night when neither of us had slept for hours) and I wondered where my life had gone, and lamented that it was possible that I’d never crawl out of the dark hole that had become my life. I was learning how to love my baby too, but this was more of a work-in-progress.

How long did this go on? The crying-on-the-floor-while-not wearing-clothes period was a few weeks, at most, although it is the salient image for me of all that time. Eventually I learned how to bake scones while holding my baby in one hand, and to breastfeed while holding a book, and there would come a time in which the baby would be a creature woven into the fabric of my life. A different fabric, sure, but it was something I could recognize. I could find my self. I learned that a mother has to insist on the self, and not to feel badly about that. I recall many trying times, but these eventually became more about abject fatigue than existential despair. When my baby was around a year old, I realized that for the most of my days were good ones now. She was getting older, and together we had learned how to make it work.

—It helps too that I became a mother when I was 29, which is relatively young these days, and even more importantly that I was wholly unaccomplished in all the fundamental ways when my child was born. In some ways, getting pregnant had seemed like a concession to life—”All right, I give in,” because there really wasn’t much else going on. And it could have been a concession had things not started to happen to me because of motherhood—creative connections made with women I met through our children, the stories motherhood inspired me to tell, the books it pushed me to read, ideas it drew me to consider, questions I’d never thought to ask before. Motherhood was to be my creative and professional blossoming in ways that were entirely separate from the baby, who was a blossom all her own. All which is to say, everything important I’ve done as a creative person I’ve done since becoming a mother. There may have been a pram in my hall, but that hall was huge and crowded with doorways, and these were rooms that I wouldn’t have been able to access any other way. The situation would be different if my life had been as creatively rich beforehand, if I felt I’d had to give something up in the process of becoming a mother. Truthfully, I’d not had that much to give.—

The book,The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, was inspired by conversations with friends about infertility. Having known without a doubt that I wanted to become a mother, I could empathize with those woman who wanted the same but could not achieve it easily. I understood too how the desire was magnified as “it” seemed less attainable. Its elusiveness makes it all the more coveted, a complex paradox too because as motherhood seems elusive for these women it is also everywhere in our mommy-saturated society (which also doesn’t respect or support actual mothers at all, but that is another story…). There are all kinds of solutions to the problem of infertility, usually delivered by people who like to suppose that these things are simple and/or people who’ve seemingly never wanted anything at all—adoption!, or there are too many people in the world anyway!—and I understand how none of these answers would suffice.

Rachel Cusk though, doesn’t seem to get it. In her recent review of two new books about women’s experiences of infertility, she is frustrated by the very premise of a woman desiring motherhood. She takes particular offence to Julia Leigh’s point in her memoir, Avalanche, that motherhood and the creative life could be compatible. Cusk quotes the following: “The truth was that many women had gone before me and found ways to lead a creative life and also be a mother. There were countless prams in countless hallways. It wasn’t ‘rocket science.’ It wasn’t either/or. There was enough space.” This Cusk takes as a “dismissal” of “the honourable testimony of female literary history of what is very much the rocket science of combining artistic endeavour with family life.” She compares Leigh’s tone to that of the Brexiters, which is kind of of the worst thing you can say about anybody these days, short of calling them ISIS. Leigh, says Cusk, is failing to interrogate a fundamental truth at the outset of her journey into motherhood, and therefore it’s inevitable that she’ll come into danger.

This is a terrific failure of empathy, I think. And also not so surprising considering Cusk’s fierce interrogation of everything, which I appreciate because it has resulted in her substantial body of work, but which I also imagine makes it hard to be a person in the world. I have always felt rather third-wave feminist when it comes to Cusk’s ideas (which is saying something, because I have never feel very third-wave), understanding her ideas on a basic level but finding her tiresome on others. All those questions in her novel, The Bradshaw Variations, in which the woman goes out to work and the husband stays home and supports the family in domestic fashion and this switch causes the family dynamic to fall apart, and this notion that success for a woman, for a feminist woman, is a male-defined one. The right to wear a suit and tie, if not literally. I never wanted that. And the idea that women pursue these ideals and end up unsatisfied seems kind of obvious to me.

I think it’s important that we critique why we make the decisions we make in our lives, to acknowledge the complicity of the patriarchy in the choices we make—whether we marry, change our names when we do, shave our legs, and wear uncomfortable shoes. I think interrogation is important. But I am not sure that the decision to have a baby necessarily falls into this category. We should interrogate it for sure, but for me, no amount of interrogation would have checked my desire to become a mother. Having a baby is not like putting on lipstick. Its more than that. And the desire for it was beyond me. I can’t explain it. I just knew.

And the thing is that Julia Leigh is right about the creative life and motherhood: people make it work. I think of Helen Sawyer Hogg, the Canadian astronomer, cataloguing star clusters during the 1930s while her baby slept in a basket beside her in the observatory. I think of Rebecca Woolf and her recent post, “Hell Yeah you can be both mother and artist.” I think of Alice Munro and Margaret Atwood and Margaret Drabble and Eula Biss and Zadie Smith and so many of my favourite writers whose work is informed by their experiences of motherhood, who don’t necessarily find the pram in the hall something to trip over. (Here’s the thing too: eventually the pram leaves the hall. Children get legs of their own. Read my friend Nathalie’s recent post, “Redundant“.) I wonder what Virginia Woolf could have written if she could have had the child she wanted. And I think of all the brilliance we would have missed out on in Rachel Cusk’s work had she not done her own grappling with all the questions that having a child raises. What would she be writing about now? Would I even know who she was?

So why shouldn’t Julia Leigh have that? Or desire it, at least. What is wrong with that, the unexamined yearning. Cusk so fixated on the origin point of Leigh’s story that the story itself is brushed away, that things go terribly wrong with Leigh’s relationship and with her health, and that work indeed gets in the way of her fertility treatments, and it’s hard to balance both, and it’s as though Cusk is writing, “See? I told you so. Not rocket science, eh? You have no idea.” As though such hardship is the inevitable outcome of the desire for a child, to be a mother. Instead of understanding that infertility is its own particular trajectory, one that is injected with hormones and other tortures, and disappointments and a mix of hope and despair. What could the journey have been, Cusk never seems to wonder, if things had been simpler, if Leigh had received the baby she desired. Plenty of strong relationships have cracked under the pressure of infertility and strong women too. It seems cruel to turn this into a moral tale.

“I just never thought it would be like this, ” is a sentence I wrote in my essay, “Love is a Let-Down” (which basically launched my entire literary career, no exaggeration). I used the line again in an essay four years later, “When Love isn’t a Let-Down After All,” after the birth of my second child, whose early days were so remarkably different from her sister’s, brighter, more salubrious and utterly infused with happiness and well-being. If I’d heard anyone describing new motherhood in such a way beforehand, I would have assumed they were lying, particularly after the darkness of postpartum days with my first baby. “So I think what we have to keep in mind as we’re sharing our stories,” I wrote, “is that stories are stories instead of facts or even destinies…The great thing about stories is that sometimes you get to write your own.”

There are so many ways to be a woman and a mother (and negotiating with infertility complicates both of these).

Which Cusk doesn’t seem to realize. And I think it’s possible she’s has been reading “the honourable testimony of female literary history” too narrowly, doing what we all do in applying our own personal lenses to other people’s stories. What I mean is that women should allowed to want to become mothers without compunction, and that (and I will never cease to be grateful to Cusk and her work for this, for she blazed a trail) when we become mothers—by in-vitro fertilization, even—sometimes we’re allowed to hate it too.

September 6, 2016

On Reading Grace Paley Wrong

The thing about years, of course, is the way they’re layer upon layer. Today I dropped Harriet off at Grade Two, which is not such a departure from Grade One—same great teacher, same beautiful classroom. And then Iris and I headed down the street, back to playschool, and it occurred to me that it was four years ago today that I first entered the playschool as a member of its community. As I did today, I showed up for my requisite two hours of cleaning to help get our (cooperative) playschool all set for the new school year. It was also the day that Zadie Smith’s NW came out, which I’d had on special order from Book City, but that is neither here nor there. I’d been about five minutes pregnant with Iris at the time, but I didn’t know it for sure—it would be another week or so before my pregnancy would be confirmed.

The thing about years, of course, is the way they’re layer upon layer. Today I dropped Harriet off at Grade Two, which is not such a departure from Grade One—same great teacher, same beautiful classroom. And then Iris and I headed down the street, back to playschool, and it occurred to me that it was four years ago today that I first entered the playschool as a member of its community. As I did today, I showed up for my requisite two hours of cleaning to help get our (cooperative) playschool all set for the new school year. It was also the day that Zadie Smith’s NW came out, which I’d had on special order from Book City, but that is neither here nor there. I’d been about five minutes pregnant with Iris at the time, but I didn’t know it for sure—it would be another week or so before my pregnancy would be confirmed.

It was a strange and vivid year, the year that Harriet was three and I was pregnant with Iris. I’ve written before about all the women I met, those hours we spent in the playground not bothering to take our children home for lunch because the conversation was just too fascinating. I remember taking my shoes off on days when it should have been too cold to be doing such things, but the sunshine had rendered the sand hot and glorious, and I liked to bury my feet in it. I remember that warmth, and those hours, and how conversations seemed to unspool, landing in messy piles all around us.

And then tonight I saw that Sarah was reading “Faith in a Tree,” by Grace Paley, and it occurred to me to get my own Collected Paley off the shelf and read Faith again. And reading it, I realized that probably I’ve been reading the story all wrong all these years. That so besotted was I by the idea of co-workers in the mother trade and those mothers in the park, and all their talk, that I hadn’t really paid much attention to the end of the story: “…Then I met women and men in different lines of work, whose minds were made up and directed out of that sexy playground by my children’s heartfelt brains, I thought more and more and every day about the world.”

I really thought that they’d been it, those mothers in the park. I really had thought she meant that this, the mothers stopping to talk, was the most important conversation. But it wasn’t, her revelation. Faith needs more than that, chatting women lounging in trees. The world needs more than that, at least if we ever expect to do anything about it. Whatever the women in the playground are doing, they’re not thinking more and more and every day about the world.

It doesn’t shock me as much as it might have, to discover that a beloved passage of a story doesn’t mean what I thought it did at all. It is possible that kernel of the truth of the matter had lodged its way into my mind. When I wrote my own post about my co-workers in the mother trade, I remarked on the fleetingness of it all, that those conversations had happened in a moment. A time when I searching for my own moorings as a parent, as a mother, and when the possibilities were still terrifyingly wide-open. I don’t really hang out in playgrounds anymore, not the way I once did, whiling away hours as the sun crossed the sky. There’s always someplace else I’ve got to be, one more thing I’ve got to get to. I suppose you could say I’m thinking more about the world, though it’s not quite so noble as that.

August 25, 2016

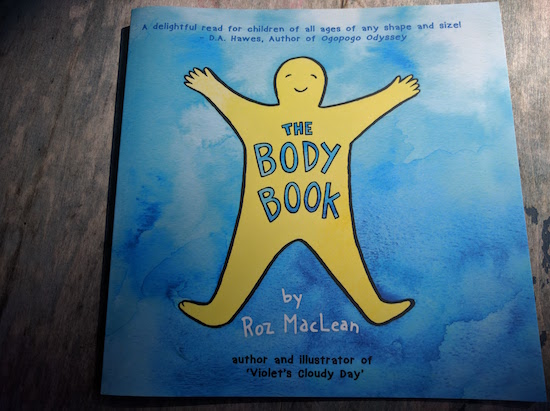

The Body Book, by Roz MacLean

If my copy of Lindy West’s Shrill hadn’t been from the library, among the countless parts I would have underlined would have included the part where she states that she’s never actually hated her body, or felt loathing toward it, but instead was just all too aware that the rest of the world thought that it didn’t conform to its standard. Which has always been my experience, for the most part (which, full disclosure, is also fairly easy for me to say, because my body has rarely deviated very radically from the standard, and let me tell you, there were some years when my body was pretty smoking’ hot [1997 and 2007 in particular were good years; maybe it’s a decennial thing, in which I’m holding out big hopes for the forthcoming annum]).

Truth: I’m still working on losing the baby weight from my second pregnancy—if by “working on losing the baby weight” you mean “eating a lot of croissants and not giving a fuck about the baby weight.”

I’ve always aspired to be quite at home in my body. When I was 17 and wrote for a teen section in our community paper, I plagiarized an article I’d read in a teen magazine about the contentment of a girl who’s eating a McDonalds hot fudge sundae—I wanted to feel that good about myself. That I had to steal the idea though is perfectly telling.

In 2001, I made my friends come with me to the nude beach at Hanlon’s Point when I stripped down to nothing and walked across a beach full of people on my way for a swim, which was truly a life-changing and empowering experience.

In 2012, I took a photograph of myself in a bathing suit and put it on the internet, which I thought was a big deal at the time (and I hadn’t even gained the baby weight!).

Last week I did the same thing again, but by now this didn’t feel remarkable. (What I wrote beside the image did though. “So glad to live in this body,” I captioned the photo, which is, in all honestly, one of the most subversive, badass things a woman can say, and what does that say about us?). And the single biggest thing that I can credit for finally attaining the self-acceptance I’ve been chasing for two decades is this one thing, or two?

I have daughters.

When I became a mother, I made several promises to myself, many of which I eventually broke (including, I will always speak kind and respectfully to my children; I will never bitch at them for reading too much [I know!—but seriously, put the book down, Harriet]; and I will never suddenly exclaim in the middle of an afternoon, “Oh my god, oh my god, all of you, now, just GO AWAY!”). But one promise I have forever stayed true to is that my children will never hear me say a negative word about my appearance. Not one. Because I think that as much as some women may dislike their appearances, all the more omnipresent is the fact that we’re kind of taught that we have to. It’s how to be a woman. Permitting yourself four almonds for a snack, and worrying about “muffin tops” and back fat. So much of it is a learned behaviour, if even by osmosis, and of course it is, because it’s everywhere.

But not in our house. There came a point when I realized our eldest was listening to every word we said and then I stopped whining, “I feel fat” and “I’m ugly!” to my husband whenever I was feeling blah (and let me tell you, other than me, there is no one involved in my personal transformation who has benefitted more than my husband, who apparently doesn’t miss my insecure neediness. Who knew?). I started delivering non-sequiturs at dinner like, “Man, I sure like my freckles,” and “I think my hair looks really pretty today” (about as naturally, at first, as I might bring up topical ideas like online porn or bullying, the kinds of talks you gotta have).

The think about fake it ’til you make it though, is that it’s kind of true. In my experience, there are only so many times you can say, “I sure love how strong my arms are” or “I really like the way I look in this dress” before you start…meaning it. Before you start actually looking for things about you to like and love, because of course it’s good for your daughters, but the thing about it that you never expected is that it’s also good for you.

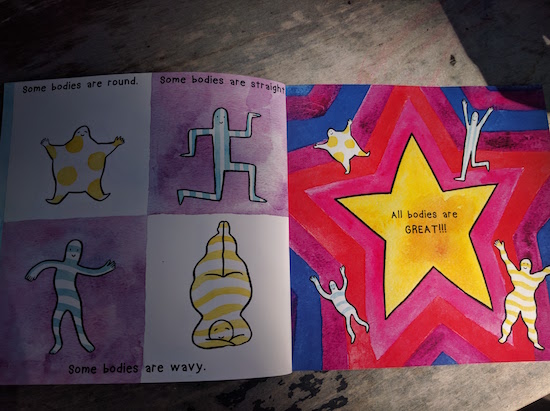

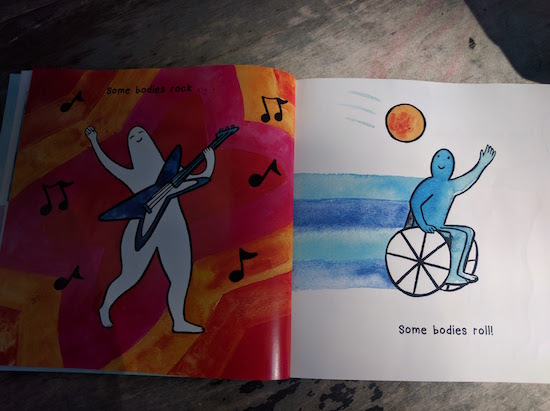

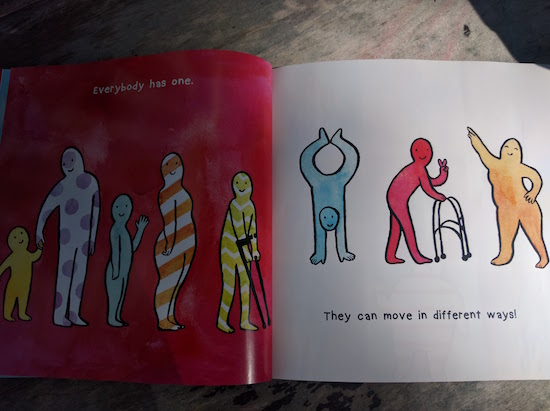

And so this is why I love Roz MacLean’s The Body Book, a simple little paperback with enormous ramifications. Because a mother is going to pick up this book for her child, and they’re both going to enjoy the story’s celebration of bodies of all kinds, shapes, sizes, and abilities: “Some bodies are round./ Some bodies are straight./ Some bodies are wavy./ All bodies are GREAT!!!” She writes about bodies that swim and play, and dance all day, and bodies that love hugs, and bodies that need space, and rocking bodies and rolling bodies, and wibbly bodies, and wobbly bodies too.

All well and good, illustrated with simple cheerful images of blobby bodies in a rainbow of colours all doing what bodies do.

The very best thing about The Body Book though, the most excellent and profound, is that every time that mother reads the book, she’s going to have to deliver the line, “I love my body. Do you love yours too?” A line that, as I’ve stated, is actually one of the bravest, most amazing things that a woman can say.

And I love that once that mother has said it enough, there is a chance she might actually mean it.

July 7, 2016

Head in the Stars

Today UofT Magazine tweeted about scientists who inspire us, which reminded me to finally write this post which has been on my mind for awhile. About a month ago, my daughters got Stargazer Lottie (who was inspired by a space-obsessed six-year-old girl AND has been “the first doll in space”), which came with a “Notable Women in Astronomy” poster. But none of the notable women were Canadian, and it occurred to me that I knew of a very notable Canadian woman in astronomy, who was Dr. Helen Sawyer Hogg. Whose work I only knew, granted, because she’d had a page in my Grade 8 science textbook and my friend and I used to make fun of her name. Which is ridiculously stupid, but the point is that I never forgot her name, and googled her years later and discovered her story was fascinating. (Do textbook writers know the indirect routes that knowledge might take, I wonder? They would probably be surprised.)

Dr. Helen Sawyer Hogg received her doctorate degree in astronomy in 1931, which is remarkable in itself. Her husband was also an astronomer and the two of them would work together until his death in 1951. Although Hogg’s work was not as valued as she was somebody’s wife, and she was often expected to do it without pay. Her first child was born in 1932 and Hogg kept the baby at work beside her in a basket while she studied star clusters at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, BC. , where her husband was employed as a research assistant. Later that year she received a grant which was exactly enough to pay for a babysitter, and I am fascinated by the idea of how liberating that must have been—and also what it must be to be consumed by cosmic things and have a baby in a basket at once. How does a person reconcile such a vast difference of scale?

Her story would never cease to be cool. After her husband’s death, she took over many of his classes at the University of Toronto, where the family had moved in the mid-1930s. She also assumed ownership of his astronomy column for the Toronto Star, which she wrote for decades (and which was collected into a bestselling book called The Stars Are for Everyone).

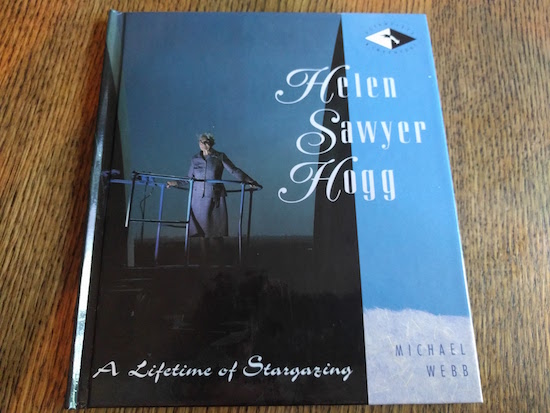

There is no full biography of Dr. Hogg. Editions of a science biography for children was published by Michael Webb in the 1980s and 1990s, and while it’s pretty informative, I’m hungry for so much more depth. And so it seems I am going to have to do some of my own digging. Helen Sawyer Hogg’s archives are at the Thomas Fisher Library at UofT, and I think I’m going to have to make some plans to start going through them. In search of what, I am not sure. A creative project? A biographical article? But there is something here, I am sure of it. I look forward to reporting back on just what I might happen to find.

May 26, 2016

7 Years Today

I continue to strongly feel that mothers should be free to write (respectfully) about their children and the lives they share together, though I suppose if my children were unusually vulnerable in some way my feelings about this would be more complicated (and they’re inevitably going to be more complicated anyway at some point in the future). I was talking about this with my friend Diana after we’d seen Vivek Shraya at the Festival of Literary Diversity discussing using her mother in her art and writing, and how she didn’t ask her mother’s permission for this. “Why can’t this license work both ways?” I wondered, though I can anticipate so many possible answers to that question. And Diana made a very good point about the dangers of mothers (it’s always mothers. I don’t suppose fathers get so tied up in knots about writing about their children, or maybe they just don’t, for various reason) writing about their children, which is that the writing might define the child before the child has a chance to define herself.

Although I don’t think I’ve ever done such a thing with Harriet. In writing or in person, I’m strongly resistant to the idea of defining my children (“she’s shy, she’s clever, she’s like this or like that”) because I don’t want such definitions to be the box they feel confined by. A person who is seven years old (or any age for that matter) should it feel absolutely possible to blossom into any kind of person, or not to be a “kind of” person at all. It certainly seems possible to me that this could happen anyway, because of how children are changing all the time. I’ve made a point of writing about both my girls on their birthdays, and from one year to the next, I don’t recognize the curious creature that went before. And that’s why writing it down is so important I think—the value of writing, “This is who she is right now.” Because tomorrow she’ll be someone else entirely, and the only thing that’s consistent is what a pleasure it is to watch her grow.

Harriet is seven today, and has been obsessed with hedgehogs ever since Anakana Schofield came to visit and brought her a small stuffed toy of one. She fills pieces of paper with all the hedgehog facts she knows, and likes to quiz us. She likes to open conversations with, “What is your favourite animal?” just so you’ll ask her the same in return. Sometimes it is a bit much. Sometimes she doesn’t care if it is or it isn’t. She loves reading comics and graphic novels, and every trip to the grocery store involves a look at the magazine stands for new Archies. She is a forthright, strong-willed character, who manages to couple such qualities with being pretty easy-going—you can take her anywhere. Her imagination is enormous. She is besotted with her sister and so kind and patient with her in a way I appreciate more than I can ever express. She eats whatever I cook for her, which is new and wonderful, even if it’s beans and spinach fritters. She loves meals out and doing Mad Libs while we wait for our food to arrive. She reads in bed until she falls asleep every night. She is a perfectly average, well-performing student in every way, except that her reading level is over the top. No surprise as she forever has her face in a book. In the past year, she has learned to swim, to skate and ride her two-wheeled scooter, so I no longer fear (mock hysterically, or not so mock) that she has a spatial awareness and balance disorder. She is determined and works very hard to learn new things, which is the most important skill a person can have. She loves her friends at school. She is brave and goes forth when I drop her off at places where she knows nobody, and expect her to get along in a way that I don’t even expect of myself. She pays a lot of attention to the news on the radio, and I don’t always perceive how much she understands. There is a whole side of Harriet I don’t even know at all, depths and fears and fascination, and sometimes a bit comes up to the surface and it floors me because of how familiar and known she is to me otherwise. But as a parent, permitting a child that space to work things out for themselves is really important. She is kind most of the time, and tries to be good, which is as good as it gets. She loves Taylor Swift and wants to be either a rock star or a scientist when she grows up. She loves to sing and dance and put on performances. She likes school and loves her teacher, and is a staunch feminist, which is cool for somebody in grade one. She is old enough to read the Rainbow Fairy books by herself now, so that I don’t have to. (Phew!) She loves Ms Marvel and superheroes and gets really annoyed by lack of female representation in any context. She still reads picture books with us, which I’m so glad about, that she has not deemed herself above childish things yet. She likes cake and ice cream and is so much fun and up for anything, and someone one told me that the ages from 6-11 were the sweet spot of having children, with most development in check and hormones not yet kicking in—and it is true.

Last night our power went out after midnight and Harriet woke up in the pitch black, her nightlight out, and she started calling me in a panic. She’d flipped out of bed and was walking into the wall trying to regain her perspective, and there I found her. I led her out of her room into our front room (and, apropos of nothing, I thought it was so funny when she was discussing the possibility of being rich recently and said, “We would have a really big front room.” Not understanding that the really rich possibly have houses wide enough to accommodate more than one room at the front) where the windows were letting in light, though houses were dark all around us. In the apartment building north of Bloor that we can see from our couch, lit windows were scattered throughout. I pointed them out to help her find her bearings. “Look,” I said. “There’s light up there.” And how she hugged me as we sat there—so solidly and wholeheartedly. It was one of the nicest things that I have ever ever experienced.

The day I found out I was pregnant with Harriet, Stuart took my picture standing before those same windows, positive pregnancy test in hand, and I look ecstatic. And it’s remarkable now think of what was taking shape just then as the picture was being taken, all the things we had no idea about. That everything we were waiting for would be so far beyond our wildest dreams.