May 31, 2023

On Momfluence

I was still five years away from motherhood the first time I came under the spell of momfluence, but of course 2004 was a very different time. I was living in Japan then and a blogger I followed about expat life in Japan took part in some sort of exchange with another blogger who was an American mother of three who lived in Malawi where her partner ran educational programming, and I was hooked. On her blog, which was called “Lucky Beans,” she used to have a blog feature called “Corners of My Home” where she could give readers glimpses into her family’s private spaces, which were usually littered with stones and pebbles collected in her youngest child’s pockets. I think her approach was Montessori-based and I was impressed by her household’s toy organization, a bin for everything and everything in its bin. None of the toys in her home were plastic, I think for Montessori reasons, but indeed this also had a particular aesthetic, and I fell in love with it. “When I have a child,” was the thing I thought, “this is the kind of mother I want to be.”

And I kind of was! There is no twist to this story. The internet has always been useful to me for aspirational purposes, but not in an aspirational aspirational way, if that makes any sense. It was never about striving for something unattainable, but instead putting an idea in my mind of an approach to parenthood that would suit my circumstances. And my aesthetic—I still hate plastic toys. But it was also less about aesthetics than practicality—I live in a small apartment and have never had that much extra money. Having less stuff and organizing it neatly just made sense, and also for the planet, because I think of all the exer-saucers that are going to outlive us all.

It helped that she wasn’t trying to sell me anything (like I said, this was 2004; she didn’t even have an Etsy shop!) and even if she was, I wouldn’t have been able to buy it. And indeed there was definitely an element of performance to her online identity (my favourite was the time she went away for a couple of weeks, and her husband took over the blog, temporarily changed the name of “Lucky Beans” to “Tough Beans: Dad’s In Charge,” and showed us a much less idyllic view of their domestic life) and surely there is one too to the fact that I’m writing this at all, and letting you know that even when my children began to acquire My Little Ponys, they were secondhand.

It’s complicated, which is the central thesis on Sara Peterson’s new book Momfluenced: Inside the Maddening, Picture-Perfect World of Mommy Influencer Culture. I have no idea how I would have been a parent before the internet starting throwing inspo my way, or how my own mom helped me figure out science projects, birthday party themes, or Halloween costumes without the help of Google (and to be fair, some of my Halloween costumes were pretty shitty). How performance is baked in to my experience of motherhood, as my blog documented my pregnancy, my bumpy intro to the mothering life, and then social media came along to help me track my children as they grew and grew and grew. Without online life, I would likely be less annoying in many ways, and I might even be less smug about my children’s wooden toys, and would they even have wooden toys at all if Lucky Beans hadn’t convinced me?

I think being an online creator, as opposed to a consumer, even as someone whose online platforms have a negligible following at best, has helped to keep my relationship to the mamasphere more positive and inspiring than soul-destroying; it’s broadened my world instead of depleting it. I wonder if it helped too that I didn’t join Instagram until 2016, by which time I’d found my feet as a parent, was not so lost in newbornland. And while I did recognize myself in some of Petersen’s profiles (I think we went apple picking twice and everybody hated it, and we don’t do that anymore; omg, I also just remembered the cookie bunting I tried to string at my daughter’s sixth birthday, which was definitely for the ‘gram, but I cut the holes wrong, and they fall fell together on a clump on the string before the whole thing fell on the floor) it has helped me that the ways I’ve been inspired by others’ online mothering has been alligned with my own inclinations anyway, that I’ve never been very interested in doing anything that I don’t want to do. (I don’t like crowds, for instance, so lining up for that iconic photo that everything else is doing is really not likely to happen.) I really do think that Instagram has inspired me to look for the spots of beauty in my life, and to try to cultivate more of that, which works to my benefit—it means there will be a bouquet of bright coloured tulips on table all summer long.

But I do wonder what the costs might be. What would my family photos look like if I hadn’t been influenced by other people’s poses? How would I be a different parent if I could be more focussed on the immediate, on the moment, rather than thinking about how it all might look from the outside, how best to capture the light. But see, would I even notice the light then? And I always notice the light. If a string of bunting hangs in the kitchen and no one is there to put it on instagram, does the bunting even bunting? (But it does! I see it every day! And oh, look at the light. Let’s take a photo. Let’s capture time for a moment, sunlight shining through the dregs of a jam jar like a Mary Pratt painting.)

January 26, 2022

Why I Talked to My Kids When I Was Struggling With Mental Health

In mid-December, when I hit my omicron wall and my mental health crumbled, it was important to me that my kids knew what was going on.

And not just because there was no hiding it. I’m not stoic at the best of times, but when the stakes are high, there’s no disguising my feelings. And I knew that any effort to keep from them what I was going through was only going to seem strange and mostly likely create far more alarm than merely acknowledging reality ever would.

So I told them. I said, “This isn’t your problem, but you need to know what I’m going through. I’m having a really hard time with my feelings and I need help and support to get better. And fixing me is not your job at all, but I need some understanding from you for that to happen.”

I told them I’d be calling the doctor and finding different ways to manage my stress. I told them, “This is what’s happening, and I’m telling you because you deserve to know and because I know you’re smart enough to get it.”

They were smart enough. And I was grateful too for the example I was setting for them, for de-stigmatizing mental health struggles and talking about these as I’d do with any other health issue. I was showing them what reaching out for support looks like, and I was also hoping that I’d eventually be able to show them that these things do get better. They would see that admitting that you need help can be what strength looks like, and I was also giving them the opportunity to rise to the occasion and be the kind and loving people that they are.

It’s a delicate balance. I am a parent and they are my children, but our relationships are still built on love and mutual respect, and these relationships are reciprocal. And yet at the same time, it’s not their job to take care of me. I don’t ever want them to feel the responsibility of that, or to worry that their own needs were being neglected as I was focusing on my own well-being. (I am fortunate too to have the support of their dad, and my family, and our community so that there is room for me to to focus on both.)

In order for me to be able to properly take care of them though, I had to take care of my own self first, and they understood that.

It helped that my fallibility was not news to them, and I was building on years of imperfection—my mental health crisis was really just more of the same!

I think some of the greatest lessons we teach our children involve showing them what it’s like to be human and to live with humans, for better or for worse.

August 31, 2021

Sidewalk Stories

There were so many children I swore I’d never have—the three-year-old with a soother; the baby in my bed; giant child in the stroller—but one I’ve successfully managed to keep at bay was Annoying Bicycle Bell child. The bane of my pedestrian existence, Annoying Bicycle Bell child is the kid riding his bike along the sidewalk who wants you to get out of the way so he can get by, and demonstrates this by ringing a bell. As though you weren’t two human beings, one of whom has a voice, the other who has ears. I found ABB child so insufferably rude, and omnipresent on my sidewalk journeys, that it got to the point where I would turn around and exclaim, “You know, you could say ‘excuse me.'”

My children always say ‘excuse me’ when they’re riding their bikes on the sidewalk. They don’t always ride their bikes on the sidewalk either, because there is an impressive spread of bike lanes throughout downtown Toronto these days that makes cycling safer and accessible for all of us, but on streets without bike lanes where traffic can be treacherous, I make the choice that most likely to have my beloved babies not be hit by a truck.

And so they ride on the sidewalk (not fast!), and they ring their bells when they’re riding past cars with occupants inside to avoid being doored (as they do when they’re riding in the cycle lanes), but when they’re faced with other people who are also using the same sidewalks in other ways, I’ve taught them to say, “Excuse me!” and then to say, “Thank you!” once the person has moved aside to let them pass.

I am writing about this now not to be smug (though I am smug, I am always smug, from which I’ve learned the lesson of smugness: “whenever I’m smug about anything, it bites me in the ass”), but instead because teaching my kids to engage with public space and other people this way is not just about sidewalks and cycling.

It teaches them their entitlement to take up space, to use the space that’s provided in a way that’s safe. It also teaches them not just entitlement, which can be obnoxious, but gracious entitlement, which is not about apology but instead about respect for our neighbours and to the people we share spaces with (and for ourselves!). Not being rude is really important.

They learn too that everything about living among other people is about negotiation, and we owe those people something, but also that they owe us the same consideration in return.

And finally, I like too the way it’s made them comfortable talking to adults, and how it makes speaking up and advocating for themselves into a habit.

Bicycle bells are important to have, but knowing how to use one’s voice is even better.

November 25, 2020

The Seasons of My Life

I have outgrown picture books…again.

Which I feel nervous even writing. If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all, and all that jazz, and I have learned through my interest in kids’ books over the last eleven years that those who create these books can be a bit sensitive about their work, about its relegation to the world of childish things. Wonderful children’s literature appeals to readers of all ages, and readers who restrict themselves to a certain age group (or genre, etc.) are missing out. All of this is true.

But it’s nothing not-nice that I’m trying to say here. Instead, it’s a matter of practicality. That for a long time, picture books were my primary way of engaging with my children and this opened up whole worlds to me, and some of those worlds seemed as real as the one I walk around in every day—but time makes you bolder and children get older, and I’m getting older too?

We still read them sometimes. Iris is only seven and we have so many great books on our shelves that all of us enjoy, books we can recite by heart. There are picture books in our library I’ll never be able to part with, and yet—we’re reading them less and less. I used to blog about picture books weekly, but now I hardly do. Everybody in our family is firmly into chapter books now, books we read on our own and the ones we read together. Picture books don’t have the same integral place in our daily life that they once did.

And none of this is remarkable. Children outgrow a lot of things, and families do too. We used to go on road trips listening to the same CD on repeat, this song with a barking dog in the chorus, because Iris cried in the car otherwise, and we don’t do that anymore. I used to get a big kick out of reading Go Dog Go in ridiculous accents, but these days the dog party is over.

But I feel a little bit disloyal, admitting to giving up on my allegiance to picture books. Or rather, moving on from it—although the new frontier, for me, is middle grade and also graphic novels, and I’m getting the same pleasure from relating to Harriet through some of the novels she’s reading as I once did when we used to examine the illustrations in Allan and Janet Ahlberg’s Peepo together, her gummy baby fingers pointing out the dog in the corner that shouldn’t be there. But I’m also trying to give her space to develop her own relationship with books and reading, one that has nothing to do with me.

And this is what happens, of course, the way things come and go. And how when they go, new things grow up in their place, which I keep reminding myself of in these moments of unprecedented change and upheaval. As businesses shut down in my neighbourhood and city and it’s enough to drive one to despair sometimes, the extent of the loss, all of it so overwhelming and hard. But even harder is trying to hold on to it all.

(And remember: a blog needs space to grow and room to wander!)

It’s okay to grow. It’s okay to change. It’s okay to change again, is what I’m thinking, and for the thing that used to define you so much and mean everything to become a spot of the horizon. And those things we loved will always be a part of who we are, because of the way that we wouldn’t have become ourselves without them.

October 18, 2020

How I Made My Children Readers: My ONE Magic Secret

Okay, as everybody knows, my children are readers because LUCK and because they happened to be born with those inclinations, and because they are fortunate that reading comes easily for their brains. LUCK also that neither of them decided to hate reading out of spite, because their mom was just way too into it. (I was anticipating this. Have done my best—and no doubt failed—not to be too much about the whole reading thing, and give them space to develop their own tastes and connection to reading that was not just an extension of mine.) This is probably 75% of the formula.

In addition, books and reading are an essential part of our family culture, they see me and their dad reading all the time, I’ve surrounded them with excellent books since before they were born, and it’s rare that they’ve ever taken a journey that didn’t end at a bookshop (and then ice cream).

But my magic secret to raising readers is none of these. My magic secret is much less wholesome, is sexist and outdated, and is available in digest form at your local grocery store. My magic secret to raising readers is ARCHIE COMICS.

And here’s why.

1 ) I buy them at the grocery store checkout, along with milk and cheese and breakfast cereal, underlining the point that reading materials can be staples, sundries just as essential as toilet paper and dish soap. They’re always appreciated, and special enough to turn up in Christmas stockings, but they’re kind of viewed there the way that socks in the stockings are. Nice to have, but ubiquitous.

2) Ubiquitous, which is to say accessible. They’re cheap. Can be taken for granted. Unremarkable. They’re just always around.

3) Being so accessible, they’re also disposable. They’re the books my children bring to the table at lunchtime because nobody cares if they get splattered with soup. Nobody has to be precious with a book like this.

4) These are also stories that ask little of their readers. They don’t require a lot of attention or brain power. They’re perfect for if you’re really tired. My daughter likes to read one as a palette cleanser after reading something intense or demanding before bed. They’re not edifying. In short, they are basically literary candy. Unlimited literary candy. And unlimited candy is basically every kid’s dream. (Just don’t tell them that they’re building literacy as a lifelong habit!)

5) I bought two comics last week when we were waiting in the drug store for our flu shots. Archie comics pass the time, and because they’re broken up into pieces, you can read them at three minute intervals or for ages and ages. Picking them up and putting them down is easy , and so they’re really easy to integrate into the course of one’s day. SEVERAL TIMES.

And because they’re so ubiquitous, there’s usually a small pile of them within arm’s reach anyway. Nobody has to go out of their way, which is just the way literacy training ought to be.

June 3, 2020

Thoughts about Being Okay

I started having panic attacks again on Monday, the kind I was having back in March when “all this” began. I’d been feeling sad and overwhelmed since Thursday, on Saturday our summer holiday got cancelled, and that afternoon helicopters circled the sky as protesters took to the street to stand up for Black people’s lives and the roar of those machines was dark and ominous. The scenes in the US were getting more and more upsetting, and Monday ended with news of the US “President” assembling troops to attack citizens in the street, and also peaceful protesters being cleared with tear gas so that dipshit could pretend he was going to church. (Dude did not know it was Monday.)

I was trembling, my heart was palpitating. I knew I was going to be in some trouble, and so after my children were in bed, my husband and I sat down to talk and try to calm me down, which helped a bit, but it still wasn’t finished, and the only way out of panic, I’ve found, is through. My mind so highly strung, and I was scared. We have a fan in our room, for ventilation and white noise, and I started imagining I was hearing the sounds of more helicopters. Trying to convince myself otherwise, but I was lying in bed awake for hours, my mind a million miles and hour, and it was the sound of people shouting and screaming I heard next, and what was happening outside? To this world?

I got up to find out, and went to the window, where perspective shifted—and I realized the sounds I was hearing were birds. I’d been up so long that the birds were awake. And the fact that birds were singing was a lulling thought, this ordinary thing instead of the nightmare I’d been imagining. And I fell asleep finally sometime around 4 am.

Spending the next day bleary-eyed and with a headache, the panic still there, and it was hard to function. I barely did. And then the panic was finished, and I still was tired, but I was calm again, and there was light to see, and the birdsong was birdsong, and world a place I recognized. Such relief in that—euphoric, even. Like an illness and the absence of pain—I was so glad to be through it.

But of course it’s not over. I feel okay again, but it’s not okay again, and I don’t think it ever has been. I was thinking too about how it’s important, perhaps even essential, for white people to feel uncomfortable. And how the greatest reason for my fear when I’m overwhelmed is usually connected to my children, my fears for this world into which I’ve brought them. And the lightness of my imaginary helicopters when compared to the concrete fears of other parents for their own Black children, to feel like that all the time. The people for whom the sounds don’t turn out to be birdsong.

I get relief from my fears—I acknowledge the privilege in that, and how different my experience is from those of other parents all over the world, in my city, even. I get to feel better, which is not a bad thing, because my panic was debilitating, short of rendering me unable to function. But the point is that now that it’s done, I need to remember that my feelings are not the end of the story of inequality and injustice, of battles that are still going on and which we need to be fighting regardless of what I’m going through.

But also that I can be okay when things are not okay, and that is okay too.

May 10, 2019

Alice At Naptime, by Shea Proulx

Sometimes I think that the story of motherhood is too big to fit onto a page, or into a book. Because having a baby is this way, and it’s that way, and it’s never one way, ever changing, impossible to properly articulate. Heather Birrell writes about this in her essay “Truth, Dare, Double Dare” in The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood. She writes:

“The trend..is toward a certain gross-out honesty—a “come join me here in the trenches” mordancy (“I just let her chew on the stroller tire!”) which, although funny and often a welcome release, leaves out the deeper resonances and rewards of being a mother and co-parent. Why is this? Because it’s hard to put your finger on the glint of joy in the dirty dishwater of drudgery. It slips away, seems a trick of the light, impossible to photograph, let alone articulate.”

But maybe you can draw it?

I am under the spell of Alice at Naptime, by Shea Proulx, who wrote in a post for 49th Shelf:

Drawings not only make clear the path of the body, but also the path of the mind, as text does, but differently from text. The world “psychedelic” is most associated with mind-altering substances, but the word breaks down from the Greek to mean “the mind…made clear.” Works of art that show clearly the mental processes involved in thinking through a subject might also be described as psychedelic, especially when the subject is inexpressible in words…

Alice at Naptime is a series of illustrations that Proulx drew of her daughter when she was a baby. “I used to draw all the time..” the book begins, “but now just at naptime.” And when Alice is napping, she draws Alice, her sleeping face set into kaleidoscopic scenes, a wonderland of strangeness, symmetry and doubleness that grows to fill the entire spread: “a symphony of Alices.” A kind of dreamland. And fittingly, for a child named Alice with illustrations that are definitely trippy, there is wonder: “Alice is strapped down so often when she naps. It looks like we’re worried she might float away.” What does Alice dream about? Proulx asks the reader, “Am I boring you?” And I remember the fascination of my sleeping child’s face, the smallness of my world then—I remember the day my child discovered causality while kicking an arch on a baby gym, and both our minds were blown, but nobody else cared. “It’s just that I’m so in love,” Proulx writes, “lost in a sea of Alice.”

What I love about this book is how Proulx shows the way that motherhood can inspire art and thought and creativity, rather than be its antithesis. That there is such profound love in the minutiae of parenting. It is like a dream, like a storm, rolling waves—and she started thinking about Alice growing, wondering who this sleeping baby will grow to be. (“What would it be like to wake up in different places all the time?”—but motherhood is a little bit like that as the years go on. My daughter turns ten this year. She’s known about causality for awhile now. Every day, we’re somewhere new.)

“I take Alice with me everywhere, even when I leave her at home.”

“Love can seem like a trap,” writes Proulx, confined to the place her baby is napping, to her baby’s needs and whims, “but I have roots now.” And it becomes clear that this book about a baby growing into a person is fundamentally the story of a woman growing into a mother—and also how she acknowledges that these sleeping napping days with Alice were only just a blink of an eye. (A dream?)

In a gorgeous afterword, Proulx writes about how it’s been years since she made these drawings. “I’m not the person I was then. You don’t become a mother all at once. You have to grow into that new self. I recognize the fragility of the tenuous identity I was sorting out as I relaxed into a new rhythm… It isn’t without sacrifice that women become mothers, or men fathers. But the gains are heady and by their nature, indescribable, as are many natural desires. I only hope I’ve done the process some small justice. I owe that to a former self, that new mom, adrift in a wonderland, wondering who she would become.”

May 10, 2019

On Mother’s Day, I’m Grateful for My Abortion

I posted this two years ago, but I feel it even more profoundly now. While people who want to restrict abortion enrage me, I also manage to feel pity for the smallness and lack of complexity of their world view, to have the limitations of their understanding on display so flagrantly.

I also had the chance to answer some questions about the essay anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, five years on from publication. You can read it over here.

On Mother’s Day, I am grateful for my abortion. Which might sound intentionally provocative, but it isn’t. If you think very hard you might be able to fathom the banality of being grateful for this one thing upon which my adult life has hinged, from which everything since has come from, every single ordinary wonderful thing. Although I wasn’t always grateful—at the time such a thing as gratitude never occurred to me. To have the freedom to make a decision about my own body and my own destiny—that sounds kind of banal as well. It was 2002 and things were politically different, or at least I was isolated enough to think they were. At the time it wouldn’t have occurred to me that The Handmaid’s Tale was prescient.

But none of that is actually what I’m thinking about today, in 2017, amidst the conversations about cultural appropriation I’ve been listening to all for the last few days—except for yesterday when I took a blessed internet sabbatical. Instead, I am grateful for my abortion for another reason, for the ability my experiences of abortion and motherhood have given me to grasp nuance, hold uncertainty and hold two ideas in my head at once. “A single thing can have two realities.” My abortion enabled me to articulate this idea, to come to know the necessity of in-betweeness. It’s a point of view that many people a great deal smarter than I am have still not been able to grasp.

I was thinking about this this morning as I read [Redacted; a person not worth thinking about specifically]’s remarkable twitter timeline which must have originated in defence of her son who has been called out for supporting a “cultural appropriation prize” in defence of another editor who has (seemingly) been set-upon by the twitter mobs. I’ve never seen such an example of one misguided offensive thing spiralling into a whirlwind of absolutely abhorrent behaviour, the kind of behaviour that would embarrass a daycare room of toddlers, with apologies to toddlers. [Redacted] daring to make a terrible thing even worse by for some reason claiming that positive experiences of Indigenous people in Canadian residential schools had been censored from the official report, which [Redacted] hasn’t even read. (“Is there no subject matter you don’t know about that you feel qualified to opine on?” asks Maggie Wente on Twitter.)

It was all so preposterous that I did the thing that no one should ever do, which is click over to [Redacted]’s timeline where she was retweeting some guy who’d tweeted, ‘Nothing says “I love you, mom” like a child you didn’t abort.’ And here, I thought, was exactly the problem. A person who’d think that was the reality of abortion and motherhood would be the person limited enough not to understand how one could support free speech and respecting Indigenous cultures. Not to see that Black Lives Matter means that all lives matter. The kind of person who doesn’t seem to get that you can find female genital mutilation appalling and still not be a raging racist, or even be a feminist who supports the right of other women to do what they like with their bodies—adorn it with a headscarf, even. That women who have abortions might be the same women who’ve mourned miscarriages, or who celebrate life-saving techniques that make it possible for babies born as early as 23 weeks to go on to thrive. These are also, I must point out, the same people who REFUSE to understand that most late-term abortions are performed on babies that were desperately wanted but nonviable due to fetal abnormalities. People who don’t get that a person like me who was so grateful for her abortion at six weeks can understand that for many women “choice” can be the lesser of two tragedies.

I am grateful for my abortion, because my experience as a pro-choice woman has informed so much of my understanding of power structures and oppression . It’s why I’m not sure “debate” is the answer, because I’ve had to stand on the street corner “debating” my bodily autonomy with a twenty year old Catholic boy, and I’m not sure it really got me anywhere. It’s why I know that “Yes, but…” is usually a better answer, and that sometimes we have to acknowledge that people really are the experts on their own lives and experiences. That listening is usually the best course. That we all have a lot to learn from each other. That sometimes the things that make us uncomfortable are the real things, and that grey areas exist for a reason and we have a lot of discover where they do.

If not for my abortion, I might think that questions have easy answers, that the world has easy answers, that life is uncomplicated, tidy and straightforward. I might not even understand that this can be true: if not for my abortion, I wouldn’t have my children. So on Mother’s Day, I’m more grateful than ever.

April 24, 2019

The Myriad Nature of Maternal Grief

Everything I know about infertility, I’ve come to understand through the analogy of abortion, which is not the opposite of infertility—though some people might have you imagine so. For your information, adoption and miscarriage are not the opposite of abortion either, as the many people who’ve had both abortions and miscarriages can definitely attest, and those women who’ve experienced adoption too. (And pay attention here, to the challenge of going beyond a single story in women’s experiences—a theme. To an insistence in our rhetoric on either/or, and maybe neither if you’re lucky, but never both.)

While I’ve not experienced infertility, I have had an abortion, which means that I’ve spent a lot of the last seventeen years thinking about reproductive choice (which delivered me the rest of my life, after all, so I spend a lot of time saying thank you). And in this thinking it occurred to me that such notions of choice must necessarily include women who want to be pregnant but aren’t, women I feel solidarity with because both experiences (wanting to be pregnant when you’re not and not wanting to be pregnant when you are) have feelings of grief and such abject despair at their core. And similarly do abortion and infertility attract the wrath of patriarchal forces, because there is nothing our society likes less than a woman who exercises agency over her destiny, who refuses to be a passive vessel.

(An additional commonality I’d never considered until reading Alexandra Kimball’s book is that abhorring abortion and dismissing the trauma of infertility both require diminishing the physical labour required to be pregnant and also that to become pregnant through reproductive technology. Abortion and infertility treatments are both considered, by those who don’t know any better, as a matter of simple “convenience,” equivocating women’s labour with, just say, a breakfast sandwich from Starbucks.)

And so Alexandra Kimball’s The Seed: Infertility is a Feminist Issue was always going to one of the books I’ve most been looking forward to this spring. (The first time I read Kimball’s work was a 2015 essay on miscarriage, which was also about her abortion, and I am always interested when abortion/miscarriage/infertility are part of the same conversation; and note: they were also all part of the conversation in the anthology I edited in 2014, The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood).

But I will admit that while I was looking forward to The Seed, its thesis (that feminism has failed infertile women) made me uncomfortable—and certainly it’s even supposed to, and it’s provocative. But what I mean is that I didn’t start reading the book completely on board, and I felt its central premise would possibly be a bit overstated. (This is kind of like when you’re white, and a racialized person tells you about their experience of racism, and you suppose they’re just being a bit sensitive.)

But it was by about page 50 and her analysis of The Handmaid’s Tale and infertility in pop culture (after the chapter on infertile women as monstrous in myth and folklore, beginning with a Babylonian epic from 18th century BC, right up to witchcraft trials just a couple of hundred years ago) that Kimball had me convinced that she was not just being sensitive. After discussing pop culture infertility in films like Fatal Attraction and The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (infertile women literally destroying the everywoman’s life) she turns to The Handmaid’s Tale, and concludes that while it is “unequivocally, a feminist text…in its world, female barrenness is not only…threatening…disgusting… it is outright oppressive, a necessary engine for patriarchy itself.”

Kimball’s analysis from here is about the tension within feminism toward motherhood in general: “an idea of motherhood as conscription into patriarchy remained central to feminist theory and action.” And how feminism’s emphasis on CONTROL in terms of reproduction left little space for those women whose experiences were beyond their control—she quotes Linda Layne on the monumental Our Bodies, Ourselves, which included miscarriage and infertility in a separate (and unillustrated) chapter at end of the book.

And who exactly gets to be in control of their reproductive lives was quite specific from the start in feminist circles—racism and classism have always played a role in this. So that even now, the experiences of racialized, queer and poor people are alienated from conversations about fertility, which itself is alienated from conversations within feminism anyway. Kimball shows numerous examples of people in general and feminists in particular being much more concerned with and disturbed by ideas about people resolving their infertility than the problem of infertility itself.

And why is it so easy for our rhetoric to remain so unconcerned about the experience of the infertile woman? “They ignore the grief,” writes Kimball, who notes that she has never felt as objectified as she did when she was infertile. “It’s difficult to see [an infertile woman] as anything other than a curiosity of capitalism, akin to people who undergo cosmetic surgery.” She writes about “the existential clusterfuck of this trauma,” how the tragedy of infertility is that resolution always seems just close enough at hand to be worth pursuing. “It’s less of a biological impulse than a narrative one, a need for coherence and sense.”

And here, Kimball begins to see the possibilities of sisterhood, of solidarity, for she finds it with a friend who a trans woman whose own experiences have been very different but who understands the extent of Kimball’s grief in a way that few other people do. (Kimball also points out that Trans-Exclusionary-Radical-Feminists find women pursuing fertility as challenging to their politics as they do trans women.) She further identifies with the the artworks of Catherine Opie and Frieda Kahlo, how they portray bodily labour and grief. “I looked at Opie’s portrait series and Kahlo’s miscarriage works frequently when I was struggling, not so much because they mirrored my own experience or made me feel less lonely, but because I was heartened by what I felt was the complexity of their stories… They demonstrate the myriad nature of maternal grief.”

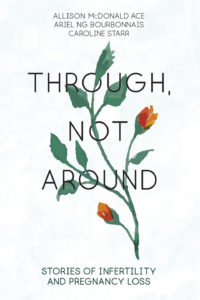

That myriad nature is explored in the essay anthology Through, Not Around: Stories of Infertility and Pregnancy Loss, edited by Allison McDonald Ace, Ariel Ng Bourbonnais and Caroline Starr, a work that challenges “the single narrative” that Kimball complicates and writes against in her cultural analysis. In Through, Not Around, the political is made personal again with 22 stories of infertility, miscarriage and stillbirth, mostly by women, but with a handful by men. Each writer is telling a story that is far from uncommon, but which was until recently taboo (and even remains so in many cultures). As Kimball writes, society is made uncomfortable by evidence of the effort and labour of motherhood, would prefer it to remain hidden so we can continue to believe it is natural, essential.

My only critique of this collection is the lack of contributor bios, because it would be interesting to see what a range of backgrounds these writers are coming from. (Although I try to think of reasons why contributor bios might be avoided here, and I can think of some answers. What happens when we let the stories speak for themselves?) My sense is that these writers come from a fairly broad spectrum of experience (although, for reasons Kimball has illuminated, racialized, queer and poor women are in the minority here, as they are in conversations about fertility in general) and that most of them are not professional writers. (The anthology was born of the online community The 16 Percent.) And so I was impressed by how excellently written most of these essays were, how they made stories out of experiences that defy the conventions of narrative at every turn. (There is a reason you rarely read a novel where someone ends up having five miscarriages.)

The grief that Kimball writes about is evident in these essays, which are stories of strength and resilience under sometimes unrelenting pressure. The point indeed is getting through, which requires action instead of passiveness. But also questions of when to try a different path forward, when to stop, and all the surprising diversions that happen along the way. Women’s lives, we read in these essays, are fraught and brutal and hard and knit with tragedy, but are also unfailingly interesting.

There are so many ways to be a woman, and to become a mother, or to be infertile, even. I’m grateful to both these books for complicating the narrative in the very best way.

February 27, 2019

Happy Parents, Happy Kids, by Ann Douglas

Early on in my career in motherhood, friends would recommend Ann Douglas’s parenting books to me on the basis that she wasn’t an ideologue. “She recognizes that there’s not just one way to do things,” I remember people explaining, because she recognized that there was not just one kind of child, or one one of family, or just one simple way to make a baby fall asleep at night. It’s a kind of pragmatism that can be rare in the parental guidance industry, and which has endeared her to a generation of readers looking for advice applicable for the world we live in as opposed to an ideal one. (Douglas’s most recent book before her latest was Parenting Through the Storm, advice for parents whose children are living with mental illness.)

Her new release is Happy Parents, Happy Kids, built on the premise that in order to make positive change in family life and the life of a child, a parent should start with herself, with her own wellbeing. A suggestion that is more important than it has ever been, perhaps, because parenthood itself has never been harder. Fashioned into a verb, made into a competitive sport on display with social media, complicated by differing philosophies and an insistence that the stakes are high for everything. Because what does the future hold? Douglas’s first chapter is called “Parenting in an Age of Anxiety,” and she goes on to illuminate how parents are challenged by questions of work/life balance, why it’s easy to always feel distracted, and how it’s too easy to lose focus on the parts of having children that are wonderful and rewarding.

Her advice on avoiding distracted parenting is really terrific (the only social media I have on my phone is Instagram, but since reading Happy Parents… I have removed the app from my phone’s main screen and turned off notifications, and my life is better for it), and she has similar suggestions, backed up with research, for connecting with your children, with your partner, for figuring out what is important to you and what your priorities are in your family life, for living with stress and hardship, overcoming past trauma, choosing calm over “stressed,” the benefits of being your authentic self as a parent, and how to resist a goal-oriented approach to being a parent: “Parenting is endlessly inefficient—and that’s okay.” Implicit in every part of this book is an understanding that families come in all shapes and sizes, with a wide variety of challenges and every kind of normal. There is a lot to work with here, and not all of it is applicable to my life at the moment, but I can foresee moments where all of it might be. This is the kind of book that would be good to keep close at hand, to dip in and out of, because you know (as the book knows) that the only sure thing have having children is that everything is changing all the time.

While “Be the change you want to see in the world” (or “Be the happy you want to see in your family”) is worthwhile and really practical advice, however, it’s only the beginning of the story, and what I love about Happy Parents, Happy Kids is that Douglas knows that. “Recognize that many of the problems that we are grappling with as parents are too big to solve on our own,” she writes in the book’s first chapter. “Systemic problems require systemic solutions, after all. So look for opportunities to join forces with other people who share your desire to create a world that’s kinder and friendlier to parents and kids.” She couples her individual-based approach to self-improvement with an awareness that society itself also needs to change, and that part of the reason that having children can be so overwhelming is because the system is stacked against us. And it’s only when we join forces and work together that things can begin to change.

The book’s final section is all about the necessity of building a village—we featured an excerpt on 49thShelf last month about the challenges and opportunities of online community. And this chapter sums up what underlines the entire book—that we can only do this all together. (I’ve also been signed up for Douglas’s newsletter, The Villager, for the last few months, with her thoughts and ideas about creating community and finding common group in an ever-shifting world, and I love every instalment.)

She writes, “The issues we’re grasping with are so much bigger than any of us, which makes them all the more challenging to resolve. The fact, it’s going to take all of us pulling together to make the situation significantly better by making changes at the personal, political, and cultural level. It may start with you, but it can’t end with you…” It’s about building a better world for the people we’re raising, and raising the kind of people that world needs.