April 22, 2020

Making Sense of What We’re Going Through

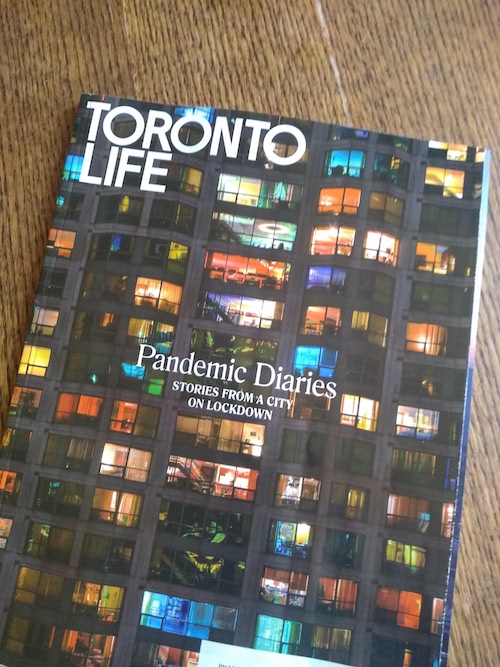

Spiritually speaking, magazines were a really terrible part of the first very bad weeks of this devastating global crisis, the new issues that arrived like vestiges of a different world, a world where there were events in March and April, arts festivals, hockey games, book launches, and photography shows, and museum exhibits. A world where one might require easy weeknight suppers, there being anything else to do on a weeknight besides cook an elaborate feast. Heartbreakingly, the April Toronto Life was “Best New Restaurants,” which is too much when you consider more than a few are unlikely to reopen again. The ads for the Winnie the Pooh exhibit at the ROM broke my heart—it was really the most delightful show, and such a draw for the museum and I am so glad we got a chance to see it before everything stopped. (I was also REALLY not into the outdated issue of The Guardian Weekly that arrived in mid-March with the headline, “The Coronavirus: Reasons Not to Panic.”)

It was an incongruity that only underlined how much absolutely nobody had seen this coming or knew what was going on, that there wasn’t a script for any of it, a template. “Unprecedented” the word that everybody was using, and I tried to stay positive by focusing on how much of what had precedent was truly awful, and also on what it meant it to learn that so much that seemed impossible actually wasn’t. But still, it felt like there was nobody at the wheel, not just in terms of leadership, and science, but also storytelling, all such a vast unknown. All the atoms in the universe just falling, and us having no idea where they’ll land. (We never do. Our current situation just exposed the illusion.)

For me, there is something tremendously heartening about the power of story. When I read Ali Smith’s Autumn in April 2017, I remember feeling hope again for the first time in almost a year. Because someone had gone and created art and story out of the mess of our time, post-Brexit and that Orange monster, and the very fact that someone could render art from it all had made me feel like maybe we were possibly a society worth salvaging after all.

And I felt the same when the May issue of Toronto Life appeared in my mailbox the other day, like we’d turned a corner somehow, the world we live in finally beginning to align with our idea of it again. It’s a miraculous issue for so many reasons, not least of which that it was put together in a matter of weeks once our reality had shifted. With eerily beautiful photography, stories of Torontonians weathering the storm, our current situation in all its mess and complexity. Context. (My understanding is that Toronto’s Spacing magazine has a similar issue coming down the pipes—I just purchased a subscription based on that promise.)

I’m so grateful for the writers who are doing the work of making sense of what we’re going through. Their work is invaluable.

November 26, 2019

Slow News

It was the Amber Alerts that started it.

But no, lets back up. I’ve been on Twitter for almost a decade, and once upon a time it was a platform that served me well—I made friends, was referred to wonderful things to read, participated in in-jokes, pondered pop-culture trivia, was able to tell people I admired just how much I liked their work. Twitter was a bubble, but the best kind. When Rob Ford was elected Mayor of Toronto in 2010, the breaking news was a devastating collective experience. Not a peep in the Twitterverse (or mine, at least) had indicated that such a thing was possible. We were talking about echo chambers. I would consider how disappointing it was that Twitter wasn’t the world.

But then came Gamergate, which changed everything, although I didn’t know it at the time. And suddenly Twitter was the place I went to argue with Pro-lifers and have men with terrible beards call me a cunt. And then eventually even those people ceased to be actual people with names and faces (and beards) and became cartoon avatars with strings of numbers after their names and the Trudeau Must Go hashtag in their bio. And now the fact that Twitter is not the world seems like an actual blessing—which is not to say that Twitter has not changed the world somewhat in its despicable likeness. But still, that the world is not Twitter is an idea I now cling to for hope.

I am so glad that I’ve gone Back to the Blog this year, for more thoughtful and meaningful connection and engagement. Because I think that Twitter and I might be totally done. We’re long past the point where I am compulsively refreshing my screen and scrolling in a vain attempt to have the world come together in some kind of narrative sense, to find the answer. (Olivia Laing’s piece on her Twitter addiction really resonated with my own experience.) I took Twitter off my phone years ago, because it really didn’t need to be my constant companion.

There is no suggestion of an answer at all anymore, no complexity. Instead, there are people who are angry about being woken up in the night by Amber Alerts, and people who are angry about people who are angry about being woken up in the night by Amber Alerts. And here I am with my phone alerts on mute, and I just have no fucks to give about any of it.

Once upon a time, I liked Twitter, because even amidst the men who called me a cunt or the Christians who called me a baby murderer, I appreciated learning about other people’s points of view (not those people, obviously) and it was really how I got my news. But I’ve since found another way.

‘But not reading the paper only kept me from not knowing things; it didn’t keep them from happening.’

‘Maybe instant information isn’t good for us. We can’t absorb it.’

—Madeleine L’Engle, A Ring of Endless Light

I still get a newspaper on the weekends, as I have for years, but in the last year, I started buying and then ordered a subscription for The Guardian Weekly. And because it’s a magazine instead of a newspaper (which always feels stale after a day), it hangs around all week, and everybody in our house reads it. There are book reviews, and culture pieces, and news from all over the world, and long-form pieces, and summaries of breaking events. It’s great, but even better? It always arrives in the mail about a week after the fact. Sometimes even longer. So that much of the “breaking news” by then has been put back together and healed over again.

And I love it.

There is context. There are facts. Instead of compulsively refreshing for it all to make sense, I have waited—and then sometimes it even does make sense by then. The news is also finite, which is splendid, and there aren’t Nazis (except in stories on the rise of white nationalism).

What would happen if you had an unpopular opinion and kept it to yourself? What would happen if your consciousness wasn’t displayed upon a ticker-tape for everyone to see? What would happen if people stopped beginning sentences with, “Am I the only one who…” or sharing unpopular opinions about food, or even having opinions at all about food.

What if you just ate your lunch?*

*After photographing it and posting it on Instagram, of course, because not all social media platforms are dead to me yet.

October 12, 2017

We love Kazoo

If you have never spent a half hour the night before Garbage Day digging through your enormous recycling bin (which is shared with two other households, one of whom eats a disproportionate amount of pizza, apparently) in search of a missing copy of a children’s magazine that might have been thrown out by accident…then you’ve probably never had a subscription to Kazoo, which described itself as “a magazine for girls who aren’t afraid to make some noise.”

And while I’ve pretty much never liked anything before it was cool (or even after it was, if I’m going to be honest) I’m very proud to say that I was a contributor to the initial Kickstarter for Kazoo six issues ago, and that I’ve never ever been sorry. Even though postal and exchange rates mean I’m paying $70 (CDN) per year for a quarterly magazine—although that might give you a better idea as to why I was digging through the garbage.

Mostly it was because Kazoo is not disposable, which is why I’m happy to pay extra money for something so entirely worth it. A magazine that’s as good as a book, and which is produced so well that it stays in tact after multiple readings. Themes have include Flight, Architecture, Nature, Steampunk, and Music, which all kinds of creative approaches to these ideas, including art, recipes, puzzles, projects, profiles, biographies and more. Each issue includes a comic strip profile of a remarkable woman, and usually these are women of colour, as well as a short story whose writers have included Emma Straub and Jane Yolen, and Meg Wolitzer is forthcoming in the next issue, according to the recent Kickstarter update (and !!!!). Get art lessons from Alison Bechdel, learn to write a song with Ani di Franco, advice on never giving up from Diana Nyad, and read a Q&A with cosmochemist Meenakshi Wadhwa under the headline, “Meet a True Rockstar.

Harriet and I have built a bridge out of marshmallows and toothpicks, we’ve made grapefruit candy and paletas under the guidance of expert cooks, she and her dad made a walking robot out of a toilet paper roll, and our most recent project was mochi ice-cream balls from the Steampunk issue (because we made mochi from rice flour using steam power—get it?).

SPOILER: I eventually found the missing magazine, and it wasn’t in the garbage, but had been put away with a bag of pipe cleaners (of course!). And good thing too, because Kazoo has more than surpassed all my dreams of an amazing magazine to inspire and empower girls, and I’m so glad it’s going strong in its second year. As they report on their website, Kazoo was “nominated for a 2017 National Magazine Award in the category of General Excellence-Special Interest and named one of the “Hottest Launches of 2016” by MIN.” I don’t actually know what MIN is, but I’m sure they’re totally right. I’m looking forward to all the good things ahead, and to renewing our subscription over and over again.

October 27, 2015

On Rereading: CNQ 93

While I wish it were otherwise, the truth is that it’s rare for a magazine to arrive on my doorstep and for me to have devoured the entire thing in a day or two. But then a magazine like Canadian Notes & Queries 93 is a rare thing. Guest-edited by Kim Jernigan, beloved former long-time editor of The New Quarterly, the issue’s focus is on rereading, inspired by the 2005 anthology, Rereadings, edited by Anne Fadiman. And basically once Anne Fadiman turns up on page 7 of your magazine (in Jernigan’s intro: “On Rereading, its Pleasures and Perils”), I’m totally hooked.

While I wish it were otherwise, the truth is that it’s rare for a magazine to arrive on my doorstep and for me to have devoured the entire thing in a day or two. But then a magazine like Canadian Notes & Queries 93 is a rare thing. Guest-edited by Kim Jernigan, beloved former long-time editor of The New Quarterly, the issue’s focus is on rereading, inspired by the 2005 anthology, Rereadings, edited by Anne Fadiman. And basically once Anne Fadiman turns up on page 7 of your magazine (in Jernigan’s intro: “On Rereading, its Pleasures and Perils”), I’m totally hooked.

(I reference Fadiman in my own essay about rereading Fear of Flying; come to think of it, my most recently published essay is about rereading too. It seems that I am the target audience for this issue of CNQ.)

Do you know Anne Fadiman? Oh, but you have to. Her essay collections Ex Libris and At Large and At Small are two of the best books I have ever read. Loving Anne Fadiman’s work is a bit like being in the world’s best secret society, except none of it’s a secret and we want everyone to join.

Anyway, an entire magazine inspired by Anne Fadiman. Think of it. In fact, go out an buy it. To read Caroline Adderson on rereading (and rewriting) her first novel, A History of Forgetting. It’s about missteps, failure, cringeworthy moments, and on what remains: “First this book tortured me, now it’s humbled me.” And Carrie Snyder on reading The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, which has changed and not changed both in what it has to tell her about being a writer: “It is the book I aspire to write…” And then Anne Marie Todkill on rereading Mrs. Dalloway. Kathy Friedman on Jane Urqhart’s Changing Heaven, which fails to measure up. (A funny aside: recently I spent an evening laughing hysterically with old friends about how strange we all were when we met nearly 20 years ago. One of us had a Jane Urquhart poster on the wall, my friend Kate remembers. This idea now seems absurd: that Urquhart had such cultural currency. I couldn’t believe it. And then not a half hour later, I was looking through an old scrapbook into which I’d etched a quotation from something by Urquhart, from The Whirlpool, maybe. I even now remember that I once wrote a poem inspired by her book, The Underpainter. All of this feels impossible now. Who knew she was such a touchstone?). And then Susan Olding on The Golden Notebook, weaving her read and her reread into a terrific story of learning lessons again and again, about fragmentation and discovery. The ways in which our readings and rereadings can go oh so wrong.

Plus there are three poems by Robyn Sarah, from her collection, My Shoes are Killing Me, which has been nominated for the Governor Generals Prize for Poetry. The kind of poems you read and that have to read aloud to whoever is sitting on the couch beside you. And a story, “Multicoloured Lights,” by Jess Taylor, from her short story collection, Pauls. And book reviews by Emily Donaldson and JC Sutcliffe. It really doesn’t get any better. (There is also work by men in the issue, although those are the ones that I skimmed…)

So go buy it. That’s all. I think it’s available on newsstands now, so go and delight in its goodness, in the worlds these pieces open and reopen, and how the best thing about literature is that we’re never ever though.

May 6, 2015

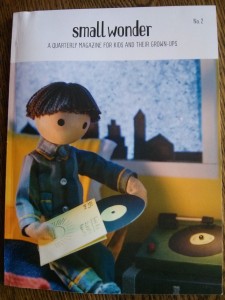

Small Wonder: A Quarterly Magazine for Kids and Their Grown-Ups

“What a book to discover in a Yorkshire cafe. I want to steal it. No??” I tweeted a couple of weeks ago, delighted to have encountered this wonderful Canadian picture book on a day trip to Ilkley. And I do have a demonstrated history of bibliokleptomania; but no, I determined. The Toast House Cafe in Ilkley was a lovely spot, a worthy home for Windy, I decided. So I left it there for someone else to come across.

“What a book to discover in a Yorkshire cafe. I want to steal it. No??” I tweeted a couple of weeks ago, delighted to have encountered this wonderful Canadian picture book on a day trip to Ilkley. And I do have a demonstrated history of bibliokleptomania; but no, I determined. The Toast House Cafe in Ilkley was a lovely spot, a worthy home for Windy, I decided. So I left it there for someone else to come across.

But then! The cafe itself joined the twitter conversation I’d been having with CanLit enthusiasts back home about the goodness of Windy and other books in the series by Robin Mitchell and Judith Steedman. “glad u didn’t steal it! I put it in our cafe for others to enjoy. I read it 2 my boys yrs ago.” Oh, how embarrassing. To be caught considering becoming red-handed. And so I tried to pass the whole thing off like a lark, oh, I’d never steal a book, which is a total lie, but at least I didn’t steal this one. (And I hope that no one else does, because I’d absolutely be blamed.)

So the creators of Windy got looped into our conversation, and it was here that I discovered that Windy and Friends is now an app. (We downloaded “Sunny’s Dark Night,” and the kids really like it. We will probably get the others.) And from Windy and Friends’ twitter feed, I learned that Sunny is a magazine cover star, and there is such a thing as Small Wonder (subtitled: “A Quarterly Magazine for Kids and Their Grown-Ups”).

So the creators of Windy got looped into our conversation, and it was here that I discovered that Windy and Friends is now an app. (We downloaded “Sunny’s Dark Night,” and the kids really like it. We will probably get the others.) And from Windy and Friends’ twitter feed, I learned that Sunny is a magazine cover star, and there is such a thing as Small Wonder (subtitled: “A Quarterly Magazine for Kids and Their Grown-Ups”).

So naturally I subscribed, which is far more noble than stealing a book, albeit just as impulsive. But I am so glad I did! Our first copy was waiting for us when we got home from vacation, and it’s just as lovely as I was hoping.

The magazine is a beautiful object with lots of thoughtfulness put into its content. It seems born of an ethos that presumes children are deserving of beautiful things, in addition to stories, adventures and wonder. There is lots of opportunities for drawing, creating, reading and dreaming in the magazine, and the issues are substantial enough that you’ll keep them around for awhile. They also recommend Singing Away the Dark by Caroline Woodward and Julie Morstad, so they clearly have impeccable taste. And pie! There is pie. Plus if you look closely, you’ll see that the pie article AND the animal silhouette feature both have Beatles references in their titles, and I don’t know if that was deliberate, but I’d probably give them credit.

Our first issue is themed for darkness, produced a few months ago when winter was drawing in, and now that winter is done, I’m hoping that means we’ll be getting our next issue soon.

November 10, 2014

Commemoration serves a political agenda

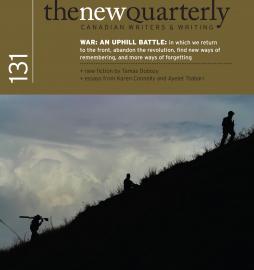

“Commemoration serves a political agenda, where nations adopt a single story that comes to represent past wars, constructed to uphold a version of the story that allows a nation to maintain a positive perception of its past. In the absence of multiple voices all speaking their own stories, nuance and contradiction are subsumed under an authoritative narrative.” –Carol Acton, “Lest We Forget: War and Memory in the 21st Century” , TNQ 131

“Commemoration serves a political agenda, where nations adopt a single story that comes to represent past wars, constructed to uphold a version of the story that allows a nation to maintain a positive perception of its past. In the absence of multiple voices all speaking their own stories, nuance and contradiction are subsumed under an authoritative narrative.” –Carol Acton, “Lest We Forget: War and Memory in the 21st Century” , TNQ 131

I renewed my subscription to The New Quarterly in July, but something went amiss (in particular: my ability to follow up on things) and so only just today did I receive my copy of TNQ 131 whose theme is “War: An Uphill Battle.” But I’m glad about that, because I think I’ve been looking for this exact read as we head into another Remembrance Day, a day that overwhelms me because I think about it oh so much. Though you mightn’t think so—I don’t wear a poppy. But not for thoughtlessness, no. Rather, I am so uncomfortable with the authoritative narrative, which seems to have become even more heightened since a mentally-ill man with a gun charged through Ottawa last month and murdered another man who was a soldier. Some might explain this as the soldier having given his life for us, which doesn’t make any sense. I am also so troubled by how war devastates soldiers’ mental and physical health—it’s as bad for them as it is for anyone. I learned about war from my grandfathers, who were both quite adamant that there should never be another one, that no human being should have to go through that. And they knew what they were talking about.

I’ve only just started reading TNQ, but am already finding it enthralling—in particular Ayelet Tsabari’s essays about her experiences in the Israeli army and growing up under the threat of war, how those experiences formed the person she’d become. A piece by journalist May Jeong about her experiences reporting from Afghanistan. (She writes, “If we are serious about bringing women’s rights to the this country, we have to end the war first.”) Stories and reflections on war and conflict, by writers including Kevin Hardcastle and Tamas Dobozy. The essay, “Mud” by the brilliant Rachel Leibowitz. “Look, Don’t Look” by Diana Fitzgerald-Bryden, on what violent and graphic images do to those of us who watch them. And Karen Connelly’s “#ItEndsHere” on the war(s) on women, along with poems from her latest book, Come Cold River. So many voices, so much nuance and contradiction. It’s a really stunning issue. I’m glad to have finally received it.

So what to do then when you’re a person who won’t wear a poppy, but who wants your daughters to remember the brutal, thankless war their great-grandfathers fought, and one before it in which their great-great-grandfather died. When you’re allergic to sentiment and glorification, you think that death doesn’t make one a hero and also that all this death and injury is such a waste, and you understand the ramifications of Canada having abandoned its role as a peacekeeper. Well, instead of a moment of silence, we talk and talk, and ask questions, and point out contradictions, and reflect, and we read, and we learn.

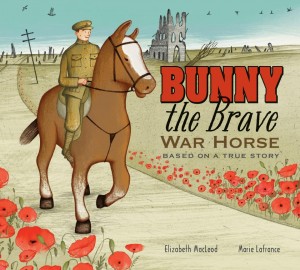

I am very pleased with the new picture book, Bunny the Brave War Horse, by Elizabeth MacLeod and Marie Lafrance, which doesn’t glorify war at all or mask its ugliness, but won’t terrify young readers either. When a soldier dies in the book, no one suggests it was worth it. But the story keeps the memory of WW1 alive, and we can strengthen the connection by pointing out that that it was really not so long ago. There is nuance here, the soldier thinking to himself that the battlefield (with its poppies) must have been a beautiful place before it was wracked and scarred by war.

I am very pleased with the new picture book, Bunny the Brave War Horse, by Elizabeth MacLeod and Marie Lafrance, which doesn’t glorify war at all or mask its ugliness, but won’t terrify young readers either. When a soldier dies in the book, no one suggests it was worth it. But the story keeps the memory of WW1 alive, and we can strengthen the connection by pointing out that that it was really not so long ago. There is nuance here, the soldier thinking to himself that the battlefield (with its poppies) must have been a beautiful place before it was wracked and scarred by war.

I also appreciate the book In Flanders Fields by Linda Granfield, which was first published in 1995 and has just been reissued. Harriet is too young for all the biographical details about John McRae and his poem, but we read the poem itself last night, accompanied by the stirring illustrations, and it made me cry. (It is possible that I so allergic to sentiment because I am particularly susceptible to it.) Yes, it’s definitely part of that authoritative narrative, which would suggest that I have indeed broken faith with those who died, but I haven’t, and neither do I wish current Canadian forces troops anything but “support”, whatever that means. Except what it means has been hijacked, and it’s all very hard, and awful and (really) unnecessary. It is.

I also appreciate the book In Flanders Fields by Linda Granfield, which was first published in 1995 and has just been reissued. Harriet is too young for all the biographical details about John McRae and his poem, but we read the poem itself last night, accompanied by the stirring illustrations, and it made me cry. (It is possible that I so allergic to sentiment because I am particularly susceptible to it.) Yes, it’s definitely part of that authoritative narrative, which would suggest that I have indeed broken faith with those who died, but I haven’t, and neither do I wish current Canadian forces troops anything but “support”, whatever that means. Except what it means has been hijacked, and it’s all very hard, and awful and (really) unnecessary. It is.

An uphill battle, indeed.

However one remembers, though, the point is just not to forget, and I haven’t. I won’t.

February 28, 2013

Brain, Child is back!

February is almost quit, and while the great outdoors buried in snow and slush, I awoke to a fantastic email in my inbox this morning that is surely a sign of spring: it is time for me to renew my subscription to Brain, Child Magazine. This news all the more remarkable because the magazine folded last year, but it has since received new life with a new owner and editor. And so I was overjoyed to renew, and am excited to have Brain, Child return to my life. It’s such a smart, insightful magazine, and yet you’d not be remiss to read it in the bathtub. It’s the only parenting magazine out there that doesn’t fundamentally exist in order to make you buy stuff and feel bad about the condition of the cake-pops at your kid’s birthday party. According to Brain, Child, there’s no such thing as cake-pops at all. Which isn’t bad, in fact, it’s fine.

February is almost quit, and while the great outdoors buried in snow and slush, I awoke to a fantastic email in my inbox this morning that is surely a sign of spring: it is time for me to renew my subscription to Brain, Child Magazine. This news all the more remarkable because the magazine folded last year, but it has since received new life with a new owner and editor. And so I was overjoyed to renew, and am excited to have Brain, Child return to my life. It’s such a smart, insightful magazine, and yet you’d not be remiss to read it in the bathtub. It’s the only parenting magazine out there that doesn’t fundamentally exist in order to make you buy stuff and feel bad about the condition of the cake-pops at your kid’s birthday party. According to Brain, Child, there’s no such thing as cake-pops at all. Which isn’t bad, in fact, it’s fine.

So subscribe. You won’t be sorry.

Further, please read this article about the woman who makes a living from mediating between parents and Nannies. You will kill yourself laughing. It begins with James van der Beek’s wife, and goes on spout amazing lines like, ““I just don’t know if she has passion about Olivia.” Then, “I don’t feel safe when you throw a Lego at my head.” And features a woman who made a mission statement for how she wanted to raise her child. It is truly the best newspaper article that I have ever, ever read.

January 10, 2013

Short fiction joy, news, and reviews.

We received the most enormous pile of packages on Tuesday, including a magazine each for Harriet and I. Mine was Canadian Notes and Queries, featuring a new short story by Caroline Adderson, and Harriet’s was Chirp, with a fabulous short story by Sara O’Leary (!!), and I loved that both of us were experiencing the joy and goodness of short fiction in fine Canadian magazines, and that Harriet gets to appreciate this fine thing from the age of 3. What a lucky girl.

We received the most enormous pile of packages on Tuesday, including a magazine each for Harriet and I. Mine was Canadian Notes and Queries, featuring a new short story by Caroline Adderson, and Harriet’s was Chirp, with a fabulous short story by Sara O’Leary (!!), and I loved that both of us were experiencing the joy and goodness of short fiction in fine Canadian magazines, and that Harriet gets to appreciate this fine thing from the age of 3. What a lucky girl.

In other news, I was quoted in this excellent piece by Anne Chudobiak in the Montreal Gazette about the CWILA count and lack of female reviewers in Canadian journals and newspapers. And my review of The Stamp Collector by Jennifer Lanthier and Francois Thisdale is now up at Quill & Quire.

March 11, 2012

"A Sister and a Brother" by Elizabeth Hay

“The snow had gone lacy, its surface melted and worked into very fine patterns like old leaves on a forest floor. In places broken twigs had slowly descended through the snow so that when a few feet away you saw what appeared to be a twig-print, then looking straight down you saw the beautiful black twig itself.”

“The snow had gone lacy, its surface melted and worked into very fine patterns like old leaves on a forest floor. In places broken twigs had slowly descended through the snow so that when a few feet away you saw what appeared to be a twig-print, then looking straight down you saw the beautiful black twig itself.”

There is something about the intimacy of Elizabeth Hay’s narrative voice and the specificity of her details that makes it difficult to really understand that her stories are imagined. In her short story “A Sister and a Brother”, which appeared in Issue 34.4 of Room Magazine, this point is underlined by her story’s structure, which moves between past and present with such fluidity, and is presented in a casual tone of reportage (“I am laying this out, because of what happened next…”) that at first glace suggests that the story has very little structure at all. Similarly with the story’s final sentences: “My brother is downstairs in the kitchen while I am up here at my desk. All is well between us.” What kind of story would you want to read that delivered you to that point? What is a story at all?

What a story is not is tidy, beginning, middle and end. Ruth narrates from a vantage point of now, able to pick and choose scenes from her past to create the effect she is intending. There are the explosive moments from her childhood (with undertones of wider violence), and the peaceful ones, and each of these is situated within its own particular contexts, which Hay alludes to (“It’s the Easter before our family comes apart in ways that I long for…”). And in the present day, in her relationship with her brother and the dynamic between them, she notes tracks of past resentments, long simmering outbursts. And then peering down into those tracks, as in the scene with twigs in the snow, the past is still there, vivid and real, just fallen down beneath the surface and out of sight.

Ruth never really liked her brother as much as she liked the idea of him, the ideal of him, and he never had any regard for her at all. She is self-aware enough: “And no doubt I am genuinely annoying as is anyone who is hesitant, bothersome, unsure of herself.” And theirs is a perpetual motion machine of Ruth provoking Peter’s ire by simply being, Peter’s ire diminishing her, Ruth resenting this diminishing and thus provoking his ire further. Driven by the hope of reaching him, which once in a while he lets her do, only to push her away again as soon as she lets her guard down.

It’s a complicated, precarious dynamic, and Hay has created in Ruth a character who mulls these things over and over, analysing questions of character and motivation in a way that it would never occur to her brother to do. She tries to see things from her brother’s point of view, sees herself from the perspective of an outsider through a friend’s story about her own detested sister, understands that it’s possible that she just doesn’t understand Peter’s sense of humour, as her parents tell her. That she has that put-upon-ness that so many women take on in middle age in their relations with their families, and her problems with Peter are no perhaps more complex than that. Not that she’ll leave it at that, because she wants something specific, and she’ll keep unpacking her baggage over and over: “How do we build a love out of the dark timber of the past?”

She says, “To hear an honest something, that’s what I live for.” But even as she’s listening, she’s pleading her case.

February 2, 2012

The New Quarterly 120: Love is Abroad

I’m behind on the times because The New Quarterly 121 has just shown up in my mailbox (which was very crowded. Apparently my downstairs neighbour has just taken out a subscription to The New Quarterly). But I still want to write about how fabulous the last issue was.

I’m behind on the times because The New Quarterly 121 has just shown up in my mailbox (which was very crowded. Apparently my downstairs neighbour has just taken out a subscription to The New Quarterly). But I still want to write about how fabulous the last issue was.

It featured the winner of the Edna Staebler Personal Essay Contest, Lisa Martin-DeMoor, whose poetry I reviewed nearly two years ago. Her essay “A Container of Light” did that brilliant thing that great essays do, which is to take something very personal personal and intimate, and shine a light upon that story in such a way that the story becomes one about something much bigger. It is particularly significant that Martin-DeMoor is writing about a miscarriage, about mourning and loss, because how do you tell a story bigger that that? But she does, and it’s beautiful: “How light is always leaping out of darkness, even when a light goes out.”

Catriona Wright’s essay “You Just Put Your Lips Together and Blow” resonated with me for personal reasons– I find the sound of whistling more grating than any other on earth. Wright addresses her own compulsive whistling (and the negative reviews it has received), and also the history and meaning of of whistling cross-culturally: “In Hawaii it is supposed to bring bad luck because it mimics the language of the Nightmarchers, ghosts of ancient Hawaiian warriors.” Totally! Also instances of whistling in pop songs, the wolf-whistle and Emmet Till, and the few remaining professional whistlers out there.

Stephen Heighton’s short story “Dialogues of Departure” was wonderful, the story of a Canadian English teacher in Japan who begins to learn Japanese through a language textbook with sinister undertones. (And it got me thinking about books stories about Canadian/Japanese experience– Heighton’s collection Flights Path of the Emperor, Catherine Hanrahan’s Lost Girls and Love Hotels, Sarah Sheard’s Almost Japanese, and even my short story “Georgia Coffee Star”.) Mark Anthony Jarman’s “Adam & Eve Saved from Drowning” was so incredibly good, Jarman’s mastery of language creating an effect that was as rich and sad as it was funny.

I also enjoyed Sara Heinonen’s “Blue Dress”, the story of a woman as lost in her life as she is in Hong Kong (and it was nice to read Heinonen’s fiction, as I enjoy her blog very much). And then “The Fires of Soweto” by Heather Davidson, and we’re told, “This is her first published story”, and I will tell you that this is what small magazines are for. What an amazing discovery. I suspect we’ll be hearing more from her.

And then if that weren’t enough, they publish two poems by one of my most beloved poets, Kerry Ryan. And another by Susan Telfer, who wrote one of my favourite books of 2010.

Every time I receive The New Quarterly, I have this weird sense that it’s been custom-edited just for my pleasure. It’s one of the great pleasures of my life to be a subscriber.