January 14, 2021

Celebration Wednesdays

#CelebrationWednesdays is a thing I made up yesterday as an excuse to be baking a cake with rainbow sprinkles in the middle of a roller coaster week. Roller coaster week in the pandemic sense, of course, which meant that I barely left the house, but the world has been hard and the weather is grey, and I’ve had plugged ears since Boxing Day that have only become worse since I started squirting random liquids into them in order to ameliorate the situation.

And so the answer was cake. (The answer is always cake.)

I made Smitten Kitchen’s confetti cake with butter cream icing, and it was so very delicious. And I determined that, for the duration, we’ll be celebrating something ever Wednesday, no matter what. And yesterday, that celebration was vaccines. The friends of ours who work in health care are beginning to get theirs. Our friends in New York are getting theirs too. A friend told me that school staff in Ontario will be among the Stage 2 vaccinations too, which is the best thing ever, and it all makes me so happy and is definitely reason to celebrate. It will be some time before I get the shot myself, I suspect, but seeing as I don’t get out much these days, I’m willing to be patient.

Right now I am reading Penelope Lively’s A House Unlocked, the story of her grandparents’ house in Southwest England and the role it played as a backdrop to the tumult of twentieth century. During World War Two, Lively’s family sheltered six small children evacuated from East London, and she put the story in a context I’d never considered before, having taken these evacuations for granted as part of history. But how bizarre it must have been—officials would come to rural homes and take stock of their capacity, and then inform residents of many people would be arriving. People who would stay for years (and had nits and wet the bed). Can you imagine going through that? What mass organization must have been required. And some of it was very disorganized—Lively writes of plans made for specific people to billeted in particular places, but when the time came, the London stations were so overwhelmed with passengers, they had no choice but to just put them on the first trains available, no matter where they were going.

She also writes about the national spirit in 1939, which I’ve never really thought a whole lot about. During the past year in particular, I’ve found myself wondering if my grandparents ever looked at each other and muttered, “Goddamn you, 1943,” but then of course they didn’t, because my grandfather was away at sea. But Lively writes about the very beginning of the war, about the catastrophic predictions for aerial bombardment from the Germans, which experts had been talking about throughout the 1930s. This was no 1914, “this will all be over by Christmas.” Lively writes, “Anyone alive to official anticipation of what would probably happen in the first days and weeks of war would have been expecting the end of the world they knew.”

The story of these mass evacuations was also one of extreme poverty, vast income inequality, a need “to preempt… mass panic and consequent breakdown of law and order” as attacks began.

Anyway, it all made me think about how there is nothing new under the sun… And about the strangeness of living through history, which I never experienced properly before the last five years or so. I was 22 on September 11, 2001, but for me that was too young to properly understand the implications of those events, or how I was connected to them. One day I think I will write something about how it was watching Mad Men that prepared me for the tumultuous times that we’ve been living through. The visceral way that the show presented what it was to experience the 1960s, the deaths of President Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. (“WHAT IS GOING ON?”)

Anyway, the great thing about Celebration Wednesdays is that they lead to Leftover Cake Thursdays.

Whatever gets you through.

October 6, 2016

Mad Men: Season Five

We’re still rewatching Mad Men, now midway through Season 5. From here on in, I’ve only seen these episodes once before, never feeling as compelled to see them again as I did with Seasons 1-3 which, it was true, were working on a very different level. I’ve even stopped taking copious notes as I watch because a) why was I taking notes in the first place b) I’ve started winter knitting projects, and I’ve not yet found way to knit and take notes (although I’m working on it) and c) I’m finding these later seasons don’t require the same puzzling-out that the earlier ones did. Characters’ motivations are clearer, the whole sense of the show is more familiar, and perhaps it’s less textured. These later seasons don’t have the same sense of grand wholeness as the others, as though these pieces are all part of a larger, and deeply intricate project. These later seasons get a bad rap too, the general sense being that things went downhill after Season 3. In a way it’s true, yet the show is still fascinating, and even more importantly (and what we were not anticipating): whenever we finish an episode we find ourselves saying, “Oh, that was was so good.”

It’s true that I was always most invested in Don and Betty as a unit, and remained as such for the rest of the series, and even though they’re both so terrible (for themselves and each other) I cherish their moments of connection after their divorce. How Betty calls Don when she learns she has a lump on her thyroid (although I notice this time that she comes home from the doctor calling for Henry, and it’s only when she can’t find him that she calls Don; she’s actually just looking for somebody to cling to, it’s not personal): “Say what you always say,” she tells him, commanding him to promise her that everything is going to be okay.

Megan Draper never really looked for me, not an actual character as much as a cipher, although this time I’m working with that and thinking that this is part of the point of her. I was always bothered by the way she seemed to be a (poorly-written) character whose personality forms as the show goes on, rather than seeming like a human being with a life behind her. But regarding this less as a problem and more of the general scheme of things has been interesting—this might be the one thing she has in common with her husband, actually, and what about her appeals to him. “Maybe I’ll be a copywriter? Maybe I’ll be an actress?” It’s kind of annoying, but I wonder if Don admires that openness, all her possibility. That they are both inventing themselves as they go—but her with such an open heart, the kind of generosity (to herself and the world) that he’ll never be able to conjure.

Ken Cosgrove has become an excellent man, just the way I remember him. The only decent guy of the lot. Shocking to rewatch Season 1 earlier this year and realize that he was thoroughly terrible. But he evolves, as Harry Crane devolves. Seeing Peggy and Stan together is really wonderful—it’s all inevitable. And I admire her character so much, and Joan too. That they aren’t binary characters—the show is so much more complicated than that. And poor Lane Pryce. There really isn’t more on that I need to say.

Season 5 is interesting, but just a little bit boring as Don struggles to behave, the tension there palpable. It’s weird though, his insistence on making this marriage work, because he doesn’t seem all that happy in it. Megan makes him seem old. Next season, it all goes wrong again, and he starts bonking his neighbour, and I might have to start taking notes again, trying to answer what has always been the question: “What IS Don Draper thinking?”

For now, whatever he’s thinking, I’m pretty sure it’s something grim.

May 19, 2016

The Suitcase

On Friday night we watched “The Suitcase”, which might be my very favourite episode of Mad Men ever (along with “The Wheel”, “Shut the Door, Have a Seat,” “Meditations in an Emergency,” and and and…). Although it’s significant to note that it’s taken us three months to get to “The Suitcase” after (re)watching the first three seasons at almost an episode daily throughout January and February. Part of this is circumstantial: we went away for the first week in March, we spent some time watching other things (including a Mad Men-inspired viewing of The Apartment, which was so wonderful), and I also stopped watching TV daily because I wanted time to read. But part of it is also the nature of Season 4, which was a turning point for the series. It was always Don Draper’s domestic situation that interested me most about the show—the contradiction of his character trying to fit the mould of husband and father—and by Season 4 that situation has disintegrated. (He eventually gets together with Megan, but their relationship never mattered to me as much as Don and Betty’s did, partly because it was hard to believe it really mattered to either of them. The stakes were never high enough.) Season 4 is also painful to watch in places—Don Draper is falling to pieces. It makes me think about the freedom Don is promised by the end of his marriage, which sounds like what he was sold as a child in “The Hobo Code” about being able to sleep so much better without the chains of a mortgage, etc. But it doesn’t turn out to be so freeing after all.

But with “The Suitcase,” Season 4 finally starts to get it together, just like Don does. It’s a pivotal episode for Peggy as well, who finally breaks up with her mediocre boyfriend and begins to see herself on equal terms with her boss. (Remember back in Season 2 where she calls him “Don” for the first time? It’s like that.) We see the depth of Don’s descent in this episode too, which we’ve only glimpsed in previous ones. He’s gross, and ugly, and mean. But he also makes himself known here in a way he doesn’t very often. At no point in this episode did I have to write, “What is Don Draper thinking?” in my notes is what I mean, and I always have to write that. When Peggy suggests that Anna is not the only person in the world who knows Don, she’s not wrong. She doesn’t know the details, but she gets him. She knows what he’s thinking, and she takes her knowledge to apply to her own situation to get where she’s going. But in this situation also, she can use it to be a friend. (And neither of these characters has very many of these.)

The episode is also really funny, delivering that legendary scene in which Duck Phillips tries to take a shit in Roger’s chair. “I killed 17 men at Okinawa.” Fantastic bathroom scenes too—Megan and Peggy, and then a heavily-pregnant Trudy Campbell and assures Peggy that she’s still young. (Also, “You’re witty…) And then the look on Pete’s face when he sees Peggy and Trudy together. They are a fascinating triumvirate. We find out Peggy’s resentment at Don taking all the credit for the GloCoat ad: “You never say thank you.” “That’s what the money is for.” They go out to eat and Don asks Peggy, “What’s the most exciting thing about a suitcase?” “Going somewhere,” she answers. They talk about how you know when you’ve had a good idea. Coming back to the question of wanting and desire, which has been a fixation of the series from the start. “I know what I’m supposed to want, but it never feels right,” says Peggy, articulating something that Don has never been able to do, but certainly understands.

They talk about how they both saw their fathers die. Don reveals that he never knew his mother. He tells Peggy that she’ll find someone, “You’re cute as hell,” and she tells him that everybody thinks she got her position by sleeping with him. He says that he didn’t sleep with her because she was unattractive, but because he has rules for work. She reminds him that he’s broken those rules. “You don’t want to start giving me morality lessons,” he tells her. “People do things.” And then he asks her about her baby—do you know how strange this is? For Don to be curious about anybody’s inner life? (I wonder if there is a connection between the mother he lost and the baby Peggy gave away.) “Do you think about it?” he asks her. She tells him, “It comes out of nowhere.”

They talk about how they both saw their fathers die. Don reveals that he never knew his mother. He tells Peggy that she’ll find someone, “You’re cute as hell,” and she tells him that everybody thinks she got her position by sleeping with him. He says that he didn’t sleep with her because she was unattractive, but because he has rules for work. She reminds him that he’s broken those rules. “You don’t want to start giving me morality lessons,” he tells her. “People do things.” And then he asks her about her baby—do you know how strange this is? For Don to be curious about anybody’s inner life? (I wonder if there is a connection between the mother he lost and the baby Peggy gave away.) “Do you think about it?” he asks her. She tells him, “It comes out of nowhere.”

And then when Don calls Stephanie and gets the news that Anna has died, and he falls apart, and they sleep together, but only in the literal sense. And then she returns to his office later that morning and he’s all fresh as though nothing has happened, and she’s gone to sleep on her office couch, and we’re all ready to see him punish her for having witnessed his vulnerability—it’s certainly happened before. But he doesn’t. And how he how he clutches her hand. All this anticipating the wonderful episode in Season Six (or Seven?) when they dance together. And also referring back to when she stroked his hand provocatively in the first episode of the series and he rejected her (and I suppose also how he takes Betty’s hand when she tells him she is pregnant at the end of Season 2—interesting how a man supposedly so fluent in ideas is most honest with a wordless gesture).

When she leaves the room, the door is left open. And Don Draper is ready to start climbing again.

February 23, 2016

What is Don Draper thinking?

“ Draper. Who knows anything about that guy? He could be Batman.” —Harry Crane

Draper. Who knows anything about that guy? He could be Batman.” —Harry Crane

“What is Don Draper thinking?” —frequent jotting in my notebook during my rewatch of Mad Men Seasons 1-3

The first time I watched Mad Men, it confused me, and the reason I’ve just rewatched the first three seasons for (perhaps?) the fourth time is that it still does, which is precisely the point. I didn’t realize then. That the very thing that compels me to the show is that so much of it and its characters remain a mystery, some of which becomes clearer as I watch it again (and again) but some of it doesn’t.

I don’t get Don Draper, but then nobody does. Inconsistency is his salient feature, that a man whose treatment of women is shameful admonishes others about being respectful to them (and his other respectful bents too, men taking off their hats in the elevator etc.), although he’s really kind of horrible to everybody. One thing I do know about him is that he gives terrible advice, and that’s why I loved the final episode of the series, where he delivers one of his sermons to Stephanie, who doesn’t buy it and thinks it’s bullshit and tells him so—that’s a huge moment, I think. His pitches and his advice are all the same, and their power is his delivery, which might convince you that it almost means something. But I’m starting to think it never does.

I am forever married to the idea of Don and Betty, and I can’t shake it. In the final episode, there is a connection between them, though I don’t think it emerges until they split. (Remember what she says when he sleeps with her while he is married to Megan? That line [paraphrased] about the worst way to get close to Don is to love him? When Betty stops doing so, she starts to really mean something to him as a person in her own right.) My insistence on their substance as a couple mostly stems from about twelve seconds in the episode “The Wheel” in which his pitch for Kodak’s Carousel is so good that he buys it himself, and comes home believing that he loves his family. We see him meet him at the door—he’s coming for Thanksgiving after all. He’s done the right thing. But then it all dissolves and we realize it was a fantasy (or a nightmare), and that his house is empty. He sits down on the step while “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” plays, and here is where I wrote, “What is Don Draper thinking?” I used to think he was regretting mistakes he’d made, that he wasn’t a better husband and father, but now I’m not so sure.

I am forever married to the idea of Don and Betty, and I can’t shake it. In the final episode, there is a connection between them, though I don’t think it emerges until they split. (Remember what she says when he sleeps with her while he is married to Megan? That line [paraphrased] about the worst way to get close to Don is to love him? When Betty stops doing so, she starts to really mean something to him as a person in her own right.) My insistence on their substance as a couple mostly stems from about twelve seconds in the episode “The Wheel” in which his pitch for Kodak’s Carousel is so good that he buys it himself, and comes home believing that he loves his family. We see him meet him at the door—he’s coming for Thanksgiving after all. He’s done the right thing. But then it all dissolves and we realize it was a fantasy (or a nightmare), and that his house is empty. He sits down on the step while “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” plays, and here is where I wrote, “What is Don Draper thinking?” I used to think he was regretting mistakes he’d made, that he wasn’t a better husband and father, but now I’m not so sure.

“It shouldn’t have happened,” Don tells Rachel Mencken during the first season, and it seems like he’s referencing his feelings toward her with the “it”, but now I’m thinking that he’s talking about his marriage. Later Betty alludes to the fact that their marriage came about suddenly—they got engaged quickly and then she got pregnant, or perhaps it was the other way around, and that was the end of their New York life. The details of everyone’s life pre 1960 are quite hazy on the show, which is strange because it’s so pointed about so many details. But for so many of these characters, you get the sense that they didn’t exist before the cameras started rolling. An example: in their entire friendship, Betty never once tells Francine that she used to model until that one episode where Francine comes over to borrow a dress? There are others like this, scenes between Don and Roger when it is hard what they’ve meant to each other, and the haziness is underlined by the weird flashbacks, dopey early Don who seems so different that the surefooted Don we know in the present (although he isn’t really—he’s just better at playing the part). There is a flashback of Don in California, goo-goo eyed about a girl he met called Betty, and it seems false to me. Similar to one that comes later in the series when we see how he hoodwinks Roger into giving him a job, though this isn’t consistent with the story that Roger tells, and Don just doesn’t seem like Don in any of these scene. But who is Don, anyway? And are his flashbacks as made-up as his pitches?

(“Who ARE you? is a question that characters ask each other throughout the series, in all manner of tones.)

So the revelation to me was that Don and Betty might have never meant anything together at all, that the Don’t Think Twice… moment wasn’t meaningful, and even if it was, that’s just twelve seconds of meaning. Plus remember later when Don tells Megan that he didn’t love his children…until he did (and I think he does, but who knows?) but when did that start? Though I think Betty does love him when the series starts, or at least the idea of him, or at least she wants to have sex with him, but he doesn’t even give her that. (Season One is very much about notions of wanting and desire, in both the consumer and the carnal senses.) “All this,” is the thing they talk about, usually with a hand gesture toward their lurid green headboard or their plaid kitchen walls. What “this” is is never clearly delineated—it seems to very much be the house and its contents (“What do you put in that freezer I bought you?” Don asks her), which is strange because neither of them really likes the house. To Betty, the house is a prison, and to Don it is an anchor of the worst kind. He longs for freedom, a lesson he learned from the hobo who told him, “Home, mortgage, a family—I couldn’t sleep. Went on the road with the clothes on my back, and now I sleep like a stone.” The trouble is that he also wants power and status, and these things come with baggage. And without the wife and house, he doesn’t have the power or the status. He needs Betty, even if he doesn’t want her.

The only proper, reciprocated connection between them, I realized, was in the third season when Don is contemplating moving up the ranks at PPL and being moved to London. He tells Betty about this, and she’s thrilled with the possibility of getting out of the suburbs, and you see that they’re good when making plans like this (and here they’re at their most Revolutionary Road-ish). It’s the ordinary they have more trouble with, the role-playing they’re really poor at, whereas their scene in Rome, when they’re both pretending to be people they aren’t, they’re amazing. The trouble is, however, that Betty knows who she is and when she’s posturing, but for Don Draper, there isn’t any difference.

I thought a lot about Pete Campbell this time, with more sympathy than I had before. I’ve always found him loathsome, and he is, but I see now that he’s not simply a foil to Don, he’s also having parallel experiences. And that he’s much more foregrounded in the show than I ever thought he was—the show begins with his marriage to Trudy and indeed they’re the only couple that stays together throughout (and I always think of Sarah’s comment now: “people who dance that well together, in such a very ambitious way, should never have parted”). Trudy is wonderful, and while Pete is loathsome, their marriage is such a partnership in a way that Don and Betty’s never is, or Don and Megan’s either. (Trudy was not a virgin when she got married—remember? She lost her virginity to the publishing guy who offers to sell Pete’s story in Boy’s Own Magazine. I think this is signifiant.) Trudy knows what she’s doing throughout, and she is the one character who really does get what she wants. Though the idea that this is somehow emasculates Pete and the show’s preoccupation with their power dynamic, and how powerful women are emotionally trying for men is one thing I find really tiresome…

Peggy too is one of the show’s anchors—the pilot is her first day of work and she develops in a way that none of the others do as the series progresses. She is also a version of Don, assembling her persona from what she sees of others just as he does, and I think we understand Don better because of Peggy’s openness with this. She is always watching, watching, while Joan is always being watched, and for each woman, this is her path to power, each one using this, respectively. But here’s another thing I got wrong the first time, another thing that confused me—Joan and Peggy throughout the series, the two paths for women to success. And I was thrown off by the ways in which they were alike and different, and none of it was entirely congruous—where is the symmetry. But no, I realized, as I watched the first three seasons this time. These are not THE two paths for women, but simply two paths, and they aren’t parallel or in opposition, but they’re both different, and each one gets each woman to where she wants to go. This is huge, I think. Peggy and Joan aren’t defined in relation to men or even to each other, but as individual people. It’s a hard thing to get one’s head around.

But a lot of things are: this is deliberate. And it happens because of the bizarre surrealness that permeates so many scenes of the show, the moments that have no footing in reality except to make viewers cringe: Sally Draper driving, Peggy stroking Don’s hand, Glen watching Betty pee, when Lois drives a lawnmower over that guy’s foot. Our reactions are visceral and sometimes the scenes are inexplicable, and all of it keeps us as viewers from getting complacent.

December 19, 2015

Light the Lights

A lot has escaped my attention these last few weeks, including that Coach House Books had a pop-up shop in their warehouse throughout December, but I heard tell of it yesterday on Twitter, a few hours before the whole thing was finished, and decided we would stop in on our way home from fetching Harriet from school, in order to satisfy my holiday book retailing fix. I got a book for Stuart and two books (surprise, surprise!) for me, and then we walked down the lane and my children began playing hopscotch on bp nichol’s poem, which really is the most practical purpose imaginable for concrete poetry, and I don’t why it had never occurred to me before.

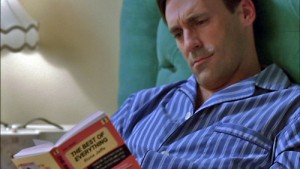

So now school’s out, and we came home from hopscotch to a mailbox stuffed with cards and parcels, as it’s been all week. Our kitchen features ridiculous amounts of chocolate and cookies, all of these balanced out by the proliferation of clementines. The Globe and Mail holiday crossword arrived today, so we now what our preoccupation for the next while will be. We began watching Mad Men from the very start last night, because I am longing to write about this series and the depth of my feelings for it, as well as to deepen my understanding, so it’s back to the beginning, little Sally Draper with a bag over her head. I think it’s the third or fourth time I’ve watched Season One, and it only gets better and better.

Plus there’s Baileys, and I’m no longer on antibiotics. And while Stuart does indeed have to work on Monday and Tuesday, we’ve already gone into vacation mode. We took a trip to the library this morning and followed with lunch out at Caplanskys, because going out for lunch is our main vacation occupation. We’re looking forward to lots of fun with friends and family this week, and skating, and going to see the Christmas windows at the Bay, and finishing our chocolate and buying more, and getting to the bottom of Betty Draper, and wrapping presents tonight (in the Saturday papers) and listening to the Phil Spector Christmas Album and Elizabeth Mitchell’s The Sounding Joy, and there will be more lunches, lazy mornings, too much indulgence, and maybe even the possibility of snow.

May 18, 2015

Night and Day

Night

We are going through a difficult period. I like framing it this way because it suggests an ending, as opposed to, We are going through a difficult eternity. “It’s just a phase,” we keep saying. “Things will get better,” but we’re beginning to sound less sure of this. It has been so long. Nearly two years since I’ve had unbroken night’s sleep. And since we came back from England, things have been awful. Iris moved downstairs into Harriet’s room to sleep, but her nighttime wake-ups have continued, plus it’s started taking her sometimes up to an hour to fall asleep, she requires us lying down beside her to do so, and then she gets up again at 11, at 1. She won’t settle unless she’s in bed with us, which would be okay (and I’m certainly not going to fight a screaming nearly-two-year-old in the middle of the night) except that then she flops and kicks and pinches my upper arms. It is unpleasant. And last night we had a babysitter booked so we could go out to a movie, but Iris refused to go to sleep. Or she would be asleep until we dared to rise and leave the room, and then her eyes would snap open and there we’d be again. Eventually, I gave the babysitter $20 and told her to go home, because we’d missed the movie. And it seems like the baby is holding us hostage, when I dare to frame the whole thing like a power struggle (which I shouldn’t do—it only makes unpleasant realities worse). We can’t go out together to anything that starts before 9pm, because no one else but Stuart and I has the patience to put Iris to bed, and now that she’s only staying asleep for 2hrs after that (if she goes to sleep at all), the world seems to have shrunk to the size of an acorn. I know that there are far worse problems to have than this one, but perspective can be hard to come by when one is having melodramatic thoughts about being subject to tyranny. Five years ago, I wrote a blog post about baby sleep books called The Trajectory of a Downward Spiral, but the trajectory of this plot is more like a head smashing into a wall. Repeatedly.

Day

But. We have had the most wonderful weekend. A weekend whose wonderfulness is currently under threat as I spend this holiday Monday morose and bereft at the end of Mad Men. The children watched Annie and ate goldfish crackers in Harriet’s room while Stuart and I watched the final episode this morning. It was so absolutely perfect. Overwhelmingly good. I feel about this show like I’ve been immersed in the narrative for six years, swimming around inside it and examining from all angles. I can’t believe it’s over, but then it isn’t really. We rewatched an episode from Season 1 on Saturday night, and it occurred to me that I’ll never really be done with it. But still, I’m sad there is no more to look forward to. So many of my feelings were invested in these characters. It all mattered a lot to me.

But. We have had the most wonderful weekend. A weekend whose wonderfulness is currently under threat as I spend this holiday Monday morose and bereft at the end of Mad Men. The children watched Annie and ate goldfish crackers in Harriet’s room while Stuart and I watched the final episode this morning. It was so absolutely perfect. Overwhelmingly good. I feel about this show like I’ve been immersed in the narrative for six years, swimming around inside it and examining from all angles. I can’t believe it’s over, but then it isn’t really. We rewatched an episode from Season 1 on Saturday night, and it occurred to me that I’ll never really be done with it. But still, I’m sad there is no more to look forward to. So many of my feelings were invested in these characters. It all mattered a lot to me.

On Saturday, we celebrated summer things with a trip to the Wychwood Barns Farmers’ Market and ate delicious food, and delighted in the fact that our children are old enough to play unattended (in mud puddles, no less) while we sit on a park bench. We also delighted in that our children were so thrilled to take the bus to the market, but were also cool with walking home. So many of my plans for this summer are inspired by Dan Rubinstein’s book, Born to Walk, and I appreciate that Harriet is big enough to be venturing further afield on foot, to be discovering her pedestrian legs without (too much) complaining. But there are also wheels, and so after Iris’s nap, she went on a bike-ride. We’re going to shed the training wheels this summer, we’ve resolved, but this is just one more thing we’re not sure about how to teach her to do—along with shoelace tying. After that, we did our planting, mostly flowers because the squirrels thwart our efforts to grow anything more substantial. Some kale and basil, but otherwise impatiens, and suddenly our deck is beautiful again. The silver maple that shades our house and yard in magnificent bloom. There is a hammock set up underneath it.

On Saturday, we celebrated summer things with a trip to the Wychwood Barns Farmers’ Market and ate delicious food, and delighted in the fact that our children are old enough to play unattended (in mud puddles, no less) while we sit on a park bench. We also delighted in that our children were so thrilled to take the bus to the market, but were also cool with walking home. So many of my plans for this summer are inspired by Dan Rubinstein’s book, Born to Walk, and I appreciate that Harriet is big enough to be venturing further afield on foot, to be discovering her pedestrian legs without (too much) complaining. But there are also wheels, and so after Iris’s nap, she went on a bike-ride. We’re going to shed the training wheels this summer, we’ve resolved, but this is just one more thing we’re not sure about how to teach her to do—along with shoelace tying. After that, we did our planting, mostly flowers because the squirrels thwart our efforts to grow anything more substantial. Some kale and basil, but otherwise impatiens, and suddenly our deck is beautiful again. The silver maple that shades our house and yard in magnificent bloom. There is a hammock set up underneath it.

Yesterday, we went on our first ravine walk of what is to be many, as we’ve declared 2015 as #SummeroftheRavines. Once again, this is a plan born of Born to Walk—to explore these wild corners of our city. We didn’t have much of a plan and climbed down into the Rosedale Valley via the path behind Castle Frank Subway Station. Unfortunately, Bayview Avenue cuts off our access to the Don Valley, which we weren’t expecting, so we had to climb back out of the ravine in order to get to where we really wanted to be, and by this point, it was nearly time to quit.

Yesterday, we went on our first ravine walk of what is to be many, as we’ve declared 2015 as #SummeroftheRavines. Once again, this is a plan born of Born to Walk—to explore these wild corners of our city. We didn’t have much of a plan and climbed down into the Rosedale Valley via the path behind Castle Frank Subway Station. Unfortunately, Bayview Avenue cuts off our access to the Don Valley, which we weren’t expecting, so we had to climb back out of the ravine in order to get to where we really wanted to be, and by this point, it was nearly time to quit.

But we had fun and the weather was beautiful, and once again, there are very little complaining. We’d compiled a Ravine Walk Bingo sheet, which gave our walk some incentive, as did the promise of lunch afterwards. We went to the House on Parliament and had the most delicious meal, our first patio of the season. And then back to the hammock. I’ve been reading H is for Hawk all weekend, which is not a great read for the emotionally fragile, I am realizing. But it’s really good, deep and layered, and totally weird. So intense. It is possible my whole family will be relieved when I’m finally completed it.

But we had fun and the weather was beautiful, and once again, there are very little complaining. We’d compiled a Ravine Walk Bingo sheet, which gave our walk some incentive, as did the promise of lunch afterwards. We went to the House on Parliament and had the most delicious meal, our first patio of the season. And then back to the hammock. I’ve been reading H is for Hawk all weekend, which is not a great read for the emotionally fragile, I am realizing. But it’s really good, deep and layered, and totally weird. So intense. It is possible my whole family will be relieved when I’m finally completed it.

Which brings me to right now where I’ve just been delivered lunch. (“Um, if I’d known you were having lunch in bed, I might not have brought you breakfast there.”) And it’s up to me to save this day from my lugubriousness and histrionics. Iris has started being capable of having actual conversations (albeit stilted ones, usually about dogs), which is extraordinary, and clearly her brain is going wild these days. If I’m able to muster perspective, it would be that these development changes are responsible for our sleep woes. If I am able to focus less on the woe. In a few weeks she will be two. Harriet turns six next Tuesday. For our family, the next month and a bit is a season of happy birthdays and anniversaries and so so many reasons for cake. (Another? My sister is having a baby tomorrow.)

Which brings me to right now where I’ve just been delivered lunch. (“Um, if I’d known you were having lunch in bed, I might not have brought you breakfast there.”) And it’s up to me to save this day from my lugubriousness and histrionics. Iris has started being capable of having actual conversations (albeit stilted ones, usually about dogs), which is extraordinary, and clearly her brain is going wild these days. If I’m able to muster perspective, it would be that these development changes are responsible for our sleep woes. If I am able to focus less on the woe. In a few weeks she will be two. Harriet turns six next Tuesday. For our family, the next month and a bit is a season of happy birthdays and anniversaries and so so many reasons for cake. (Another? My sister is having a baby tomorrow.)

It all goes by so fast.

May 14, 2015

Drive by Kellen Hatanaka

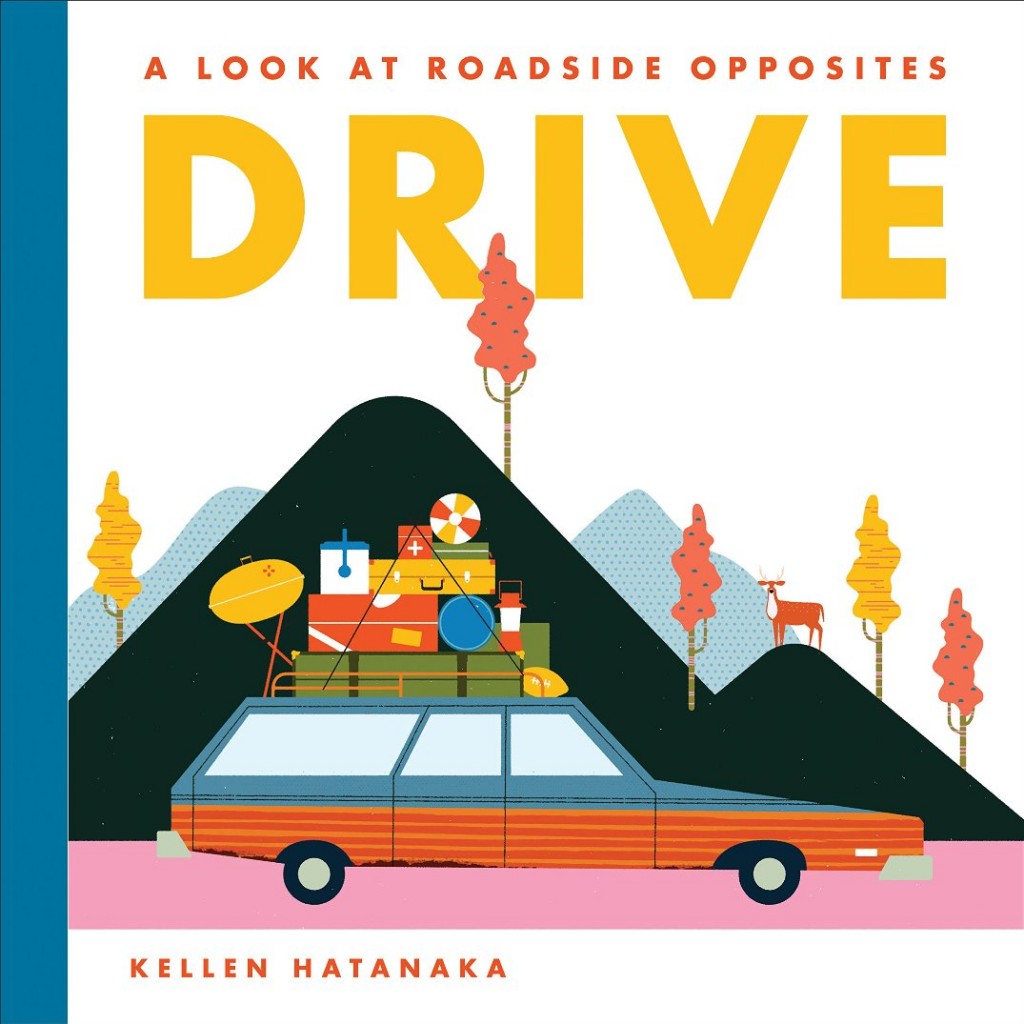

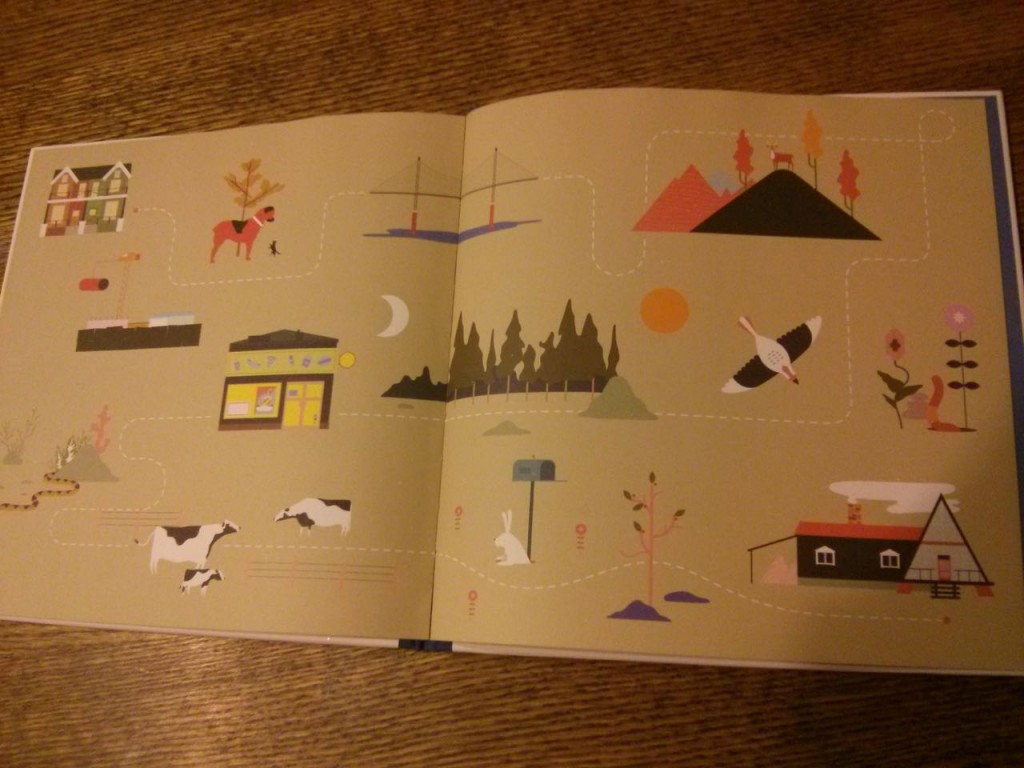

Mad Men ends on Sunday, after years and years, and in tribute to my favourite show, I’ve picked a picture book this week with a similar aesthetic. I think Betty Draper even owned that station wagon exactly. Drive: A Look at Roadside Opposites is the second book by Kellen Hatanaka, whose Work: An Occupational ABC was on my Hipster Picture Book list last year. While this new book is similarly focussed on design, it’s got more of a narrative, and I like it even better than the first one.

Drive is the story of a journey toward a summer holiday, from the city to the country, and therefore a natural setting for I-spying opposites. The car is packed with summer things—a barbecue and beach balls—and we can only imagine the Are We There Yets? before they finally arrive.

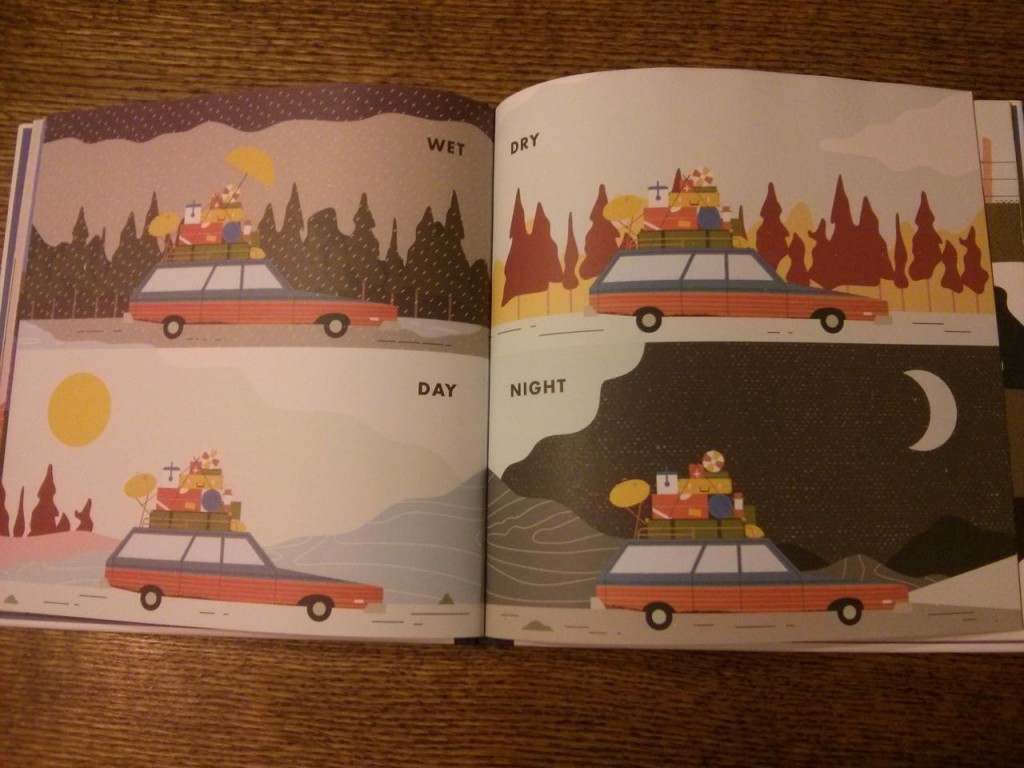

But in the meantime, there is looking out the window. Big, small. Above, below. Winding roads and straight ones.

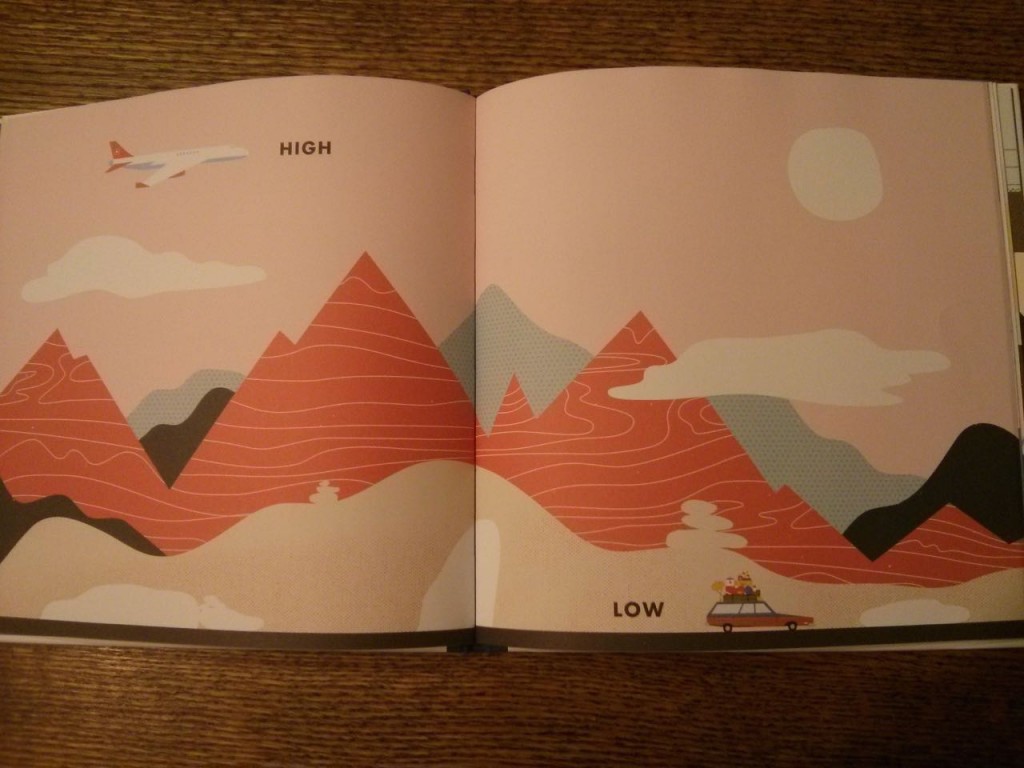

With all of these Don Draper is actually DB Cooper rumours, this page seems particular eerie.

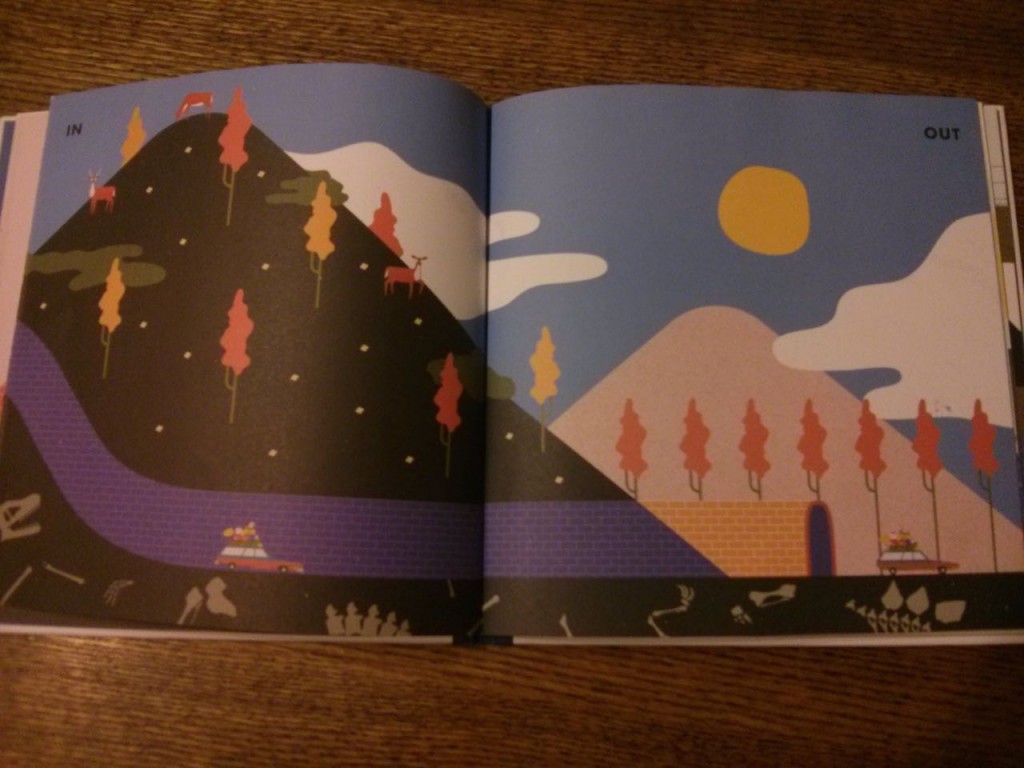

The illustrations are fantastic, full of funny and interesting details. We particularly like the dinosaurs bones under the mountain in the image below. As with his previous book, Hatanaka plays up the unexpected—I love the “Worm’s Eye View” that opens up into a four page spread of “Bird’s Eye View”, the world spread out below, patchwork fields and the winding road, the car viewed straight down on the roof-rack.

At the end, there is a map, a dotted line tracing the journey from place to place and suddenly the whole thing all comes together—the same story from another perspective.

Drive would be an excellent book to take on the road (perhaps along with See You Next Year?), giving a young reader lots to look at when there’s nothing to see out the window, and perhaps inspiring her to look again and closer at the weird and wonderful world whizzing by outside.

- For more on Mad Men and children’s books, see my post, “What Sally Draper Must Have Been Reading“

April 6, 2015

Departures and Arrivals

We leave for our trip this week, and I keep waiting for that lull between our departure and the time in which nobody in our family is sick, but the window for such a thing is disappearing, and I am so very tired. And sick, again. There was about five minutes on Friday when I wasn’t, and then cold symptoms returned on Saturday morning shortly after my child threw up in a shoe store, which was a brand new milestone for all of us. But nevertheless, Easter was had, a holiday we celebrate for its pagan roots and not the Jesus bits. We’re all about the eggs, and the new life that comes with spring—I met a baby today who turns two weeks old tomorrow, and she was a miracle unfolding. We had a lovely visit with my parents, and saw friends on other days, and Harriet and Iris got the new Annie movie on DVD, and Harriet has watched it five times already. There are crocuses across the street. We are assembling our playlist, a CD of driving tunes for the journey from Berkshire to Lancashire (which I’m the smallest bit nervous about, Iris having just now decided that she hates cars. “Car, no. Car, no.”)

We leave for our trip this week, and I keep waiting for that lull between our departure and the time in which nobody in our family is sick, but the window for such a thing is disappearing, and I am so very tired. And sick, again. There was about five minutes on Friday when I wasn’t, and then cold symptoms returned on Saturday morning shortly after my child threw up in a shoe store, which was a brand new milestone for all of us. But nevertheless, Easter was had, a holiday we celebrate for its pagan roots and not the Jesus bits. We’re all about the eggs, and the new life that comes with spring—I met a baby today who turns two weeks old tomorrow, and she was a miracle unfolding. We had a lovely visit with my parents, and saw friends on other days, and Harriet and Iris got the new Annie movie on DVD, and Harriet has watched it five times already. There are crocuses across the street. We are assembling our playlist, a CD of driving tunes for the journey from Berkshire to Lancashire (which I’m the smallest bit nervous about, Iris having just now decided that she hates cars. “Car, no. Car, no.”)

Tonight we’re watching the new Mad Men, which premiered last night, but we watch it on download from iTunes so are behind the people who watch it on TV. I don’t know what I’m going to do in a world without Mad Men, a show that has been such a huge part of my life for years now and which has seriously informed my reading life too. It’s a good time to re-share The Canadian Mad Men Reading List, which I made last year, and am seriously proud of. Oh, Stacey MacAindra. Maybe I’ll finally get around to finishing The Collected Stories of John Cheever. I still haven’t read “The Swimmer.” I’ve been saving it, I think, of the post-Mad Men world. In which I am probably going to go right back to Season One.

Tonight we’re watching the new Mad Men, which premiered last night, but we watch it on download from iTunes so are behind the people who watch it on TV. I don’t know what I’m going to do in a world without Mad Men, a show that has been such a huge part of my life for years now and which has seriously informed my reading life too. It’s a good time to re-share The Canadian Mad Men Reading List, which I made last year, and am seriously proud of. Oh, Stacey MacAindra. Maybe I’ll finally get around to finishing The Collected Stories of John Cheever. I still haven’t read “The Swimmer.” I’ve been saving it, I think, of the post-Mad Men world. In which I am probably going to go right back to Season One.

Today I found a poem about motherhood, bpNichol Lane, Coach House Books and Huron Playschool, written by Chantel Lavoie for the Brick Books Celebrating Canadian Poetry Project. I find myself struck by the poem and the various ways it connects with my life, and how literature and motherhood and the fabric of the city are all so enmeshed. Particularly in this neighbourhood.

And finally, I am in a peculiar situation book-wise. I don’t know what books to take with me on vacation. Now, on a certain level, bringing any books on vacation is simply stupid because all I ever do when we go to England is buy books. And when I look at my to-be-read shelf now, no contenders jump out on me—nothing good for an airplane, nothing I am truly destined to love, no book with which I’d be thrilled to be holed up with in an airport terminal. You can’t take chances in a situation like this! So I have decided…to bring no books with me. This is truly the wildest and craziest thing I’ve ever done. This year, at least… To pick up a book at the airport, and trust I’ll find the right one there, and then live book to book. No safety net. This is terrifying. And yet potentially exhilarating, rich with adventure. The book nerd’s equivalent of jumping out of the sky.

May 8, 2014

Unexpected Mad Men read: Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing

I wasn’t expecting a Mad Men read when we started Tales of Fourth Grade Nothing a couple of weeks ago (which is significant for being Harriet’s first Judy Blume). I remembered the stories in the book so well, but I’d forgotten the details, or maybe I just hadn’t noticed at the time. Like how its backdrop was 1970s’ New York City, and how Peter is allowed to walk to Central Park alone to play with his friends when the weather is good, but he’s wary of muggers. “I’ve never been mugged. But sooner or later, I probably will be. My father’s told me what to do. Give the muggers what they want and try not to get hit on the head.” His parents are concerned about dope-smokers who hang out in the park. “But taking dope is even dumber than smoking, so nobody’s going to hook me!”

I wasn’t expecting a Mad Men read when we started Tales of Fourth Grade Nothing a couple of weeks ago (which is significant for being Harriet’s first Judy Blume). I remembered the stories in the book so well, but I’d forgotten the details, or maybe I just hadn’t noticed at the time. Like how its backdrop was 1970s’ New York City, and how Peter is allowed to walk to Central Park alone to play with his friends when the weather is good, but he’s wary of muggers. “I’ve never been mugged. But sooner or later, I probably will be. My father’s told me what to do. Give the muggers what they want and try not to get hit on the head.” His parents are concerned about dope-smokers who hang out in the park. “But taking dope is even dumber than smoking, so nobody’s going to hook me!”

Warren Hatcher is totally Don Draper, though I suspect not as dashing and probably not so lucky with the ladies. He works for an advertising agency and, like Don in his more domestic days, is expected to use his status as family man to further himself professionally and win accounts. Because of the antics of his youngest son, he ends up losing the Juicy-O account. When his wife goes out of town for a few days, he brings the kids to the office and leaves them in the care of his secretary, Janet, who seems fine with the amusement of small children being part of her job description. While at the office, Peter and Fudge stumble onto auditions for the Toddle Bike commercial, and Fudge captures the heart of the company’s president. As ever, disaster ensues, but Fudge gets to be on TV. The next day, Warren/Don takes the kids to the movies, even though Fudge is only just three, and he sits Fudge on the end of the row. Unsurprisingly, he goes missing. And even without the disaster, it would have been a very Don Draper parenting move.

Warren Hatcher is totally Don Draper, though I suspect not as dashing and probably not so lucky with the ladies. He works for an advertising agency and, like Don in his more domestic days, is expected to use his status as family man to further himself professionally and win accounts. Because of the antics of his youngest son, he ends up losing the Juicy-O account. When his wife goes out of town for a few days, he brings the kids to the office and leaves them in the care of his secretary, Janet, who seems fine with the amusement of small children being part of her job description. While at the office, Peter and Fudge stumble onto auditions for the Toddle Bike commercial, and Fudge captures the heart of the company’s president. As ever, disaster ensues, but Fudge gets to be on TV. The next day, Warren/Don takes the kids to the movies, even though Fudge is only just three, and he sits Fudge on the end of the row. Unsurprisingly, he goes missing. And even without the disaster, it would have been a very Don Draper parenting move.

He even makes omelettes, which I remember as a Don Draper speciality! His children can’t believe he knows how to cook at all, and he actually doesn’t, because the omelettes are inedible. We finished the book amused by the Don Draper-ness, but a bit disappointed in the gender roles reinforced in the book. But then it was first published in 1972, so what do you expect?

Except that we started reading Superfudge, and it seems that Don Draper is evolving. He’s taking a year’s leave from the agency to try writing a book about the history of advertising and its effect on the American people. The idea is especially appealing to him because he’s looking forward to staying home with his family, to experiencing his daughter’s babyhood when he’d been absent for the other two. He’s even started changing diapers! No word if he’s cut down on the smoking or the drinking though, or of what Roger Sterling thinks of the sea change.

November 12, 2013

The Fire Dwellers: Margaret Laurence and Bettys Friedan and Draper

If Margaret Laurence’s The Fire Dwellers were published today, critics would be lauding its uncanny sense of the contemporary moment, how Laurence dares to voice the unspoken truths of motherhood, her pitch-perfect portrayal of the subtleties of maternal ambivalence. Published in 1969, Laurence’s fourth novel belongs with Atwood’s The Edible Woman and Phyllis Brett Young’s The Torontonians as essential Canadian novels born out of the world of The Feminine Mystique. Which puts the book’s contemporary moment-ness in question, but then the lessons of The Fire Dwellers don’t tend to be the kind we pass on to our daughters, however much to their detriment. Not that they’d listen anyway. Isn’t it funny how the history of feminism is so profoundly uncumulative? How we have to learn it for ourselves over and over, and it’s a revolution/revelation every time?

If Margaret Laurence’s The Fire Dwellers were published today, critics would be lauding its uncanny sense of the contemporary moment, how Laurence dares to voice the unspoken truths of motherhood, her pitch-perfect portrayal of the subtleties of maternal ambivalence. Published in 1969, Laurence’s fourth novel belongs with Atwood’s The Edible Woman and Phyllis Brett Young’s The Torontonians as essential Canadian novels born out of the world of The Feminine Mystique. Which puts the book’s contemporary moment-ness in question, but then the lessons of The Fire Dwellers don’t tend to be the kind we pass on to our daughters, however much to their detriment. Not that they’d listen anyway. Isn’t it funny how the history of feminism is so profoundly uncumulative? How we have to learn it for ourselves over and over, and it’s a revolution/revelation every time?

But then The Fire Dwellers is largely about su ch disconnectedness, between generations, between spouses, friends, between the personal and the political, and—in the case of protagonist Stacey MacAindra—from one’s self, from one’s own life. Stacey is 39, sixteen years married, mother of 4, and according to the sensationalist copy on my Seal Book paperback, she’s looking for a lover. Which isn’t really true, though it’s probably a good way to sell a paperback. Anyone who has read the book, however, will tell you that she is looking for is herself beyond her oppressive roles of wife and mother. Roles which aren’t strictly oppressive; “They nourish me and they devour me too,” she writes of her children, and it’s in this in-between where she’s stuck, imagining the various ways she is destroying her children (by being overbearing, by too much attention, with her anger, all of these suggestions underlined by “helpful” magazine articles suggesting as much) and/or all the ways they would be destroyed anyway if she somehow managed to get away from them.

ch disconnectedness, between generations, between spouses, friends, between the personal and the political, and—in the case of protagonist Stacey MacAindra—from one’s self, from one’s own life. Stacey is 39, sixteen years married, mother of 4, and according to the sensationalist copy on my Seal Book paperback, she’s looking for a lover. Which isn’t really true, though it’s probably a good way to sell a paperback. Anyone who has read the book, however, will tell you that she is looking for is herself beyond her oppressive roles of wife and mother. Roles which aren’t strictly oppressive; “They nourish me and they devour me too,” she writes of her children, and it’s in this in-between where she’s stuck, imagining the various ways she is destroying her children (by being overbearing, by too much attention, with her anger, all of these suggestions underlined by “helpful” magazine articles suggesting as much) and/or all the ways they would be destroyed anyway if she somehow managed to get away from them.

Through the novel, Laurence plays headlines from television news programs, broadcasting war, turmoil and unrest around the world. In one sense, the headlines are juxtaposed with the domestic, but we soon come to see that these are parallel, that the home-front is no safe haven after all.

Through the novel, Laurence plays headlines from television news programs, broadcasting war, turmoil and unrest around the world. In one sense, the headlines are juxtaposed with the domestic, but we soon come to see that these are parallel, that the home-front is no safe haven after all.

“I can’t forget that piece in the paper. Young mother killed her two-month-old infant by smothering it. I wondered how that sort of thing could ever happen. But maybe it was only that the baby was crying, and she didn’t know what to do, and was maybe frantic about other things entirely, and suddenly she found she had stopped the noise. I cannot think this way. I must not.”

Children are hit by cars and killed, neighbours attempt suicide, Stacey and her husband worry about money, she fears that Mac is sleeping with his secretary, her youngest still isn’t talking (and what has she done to her to make this go wrong, Stacey wonders), and just as terrifying as the suffocating demands of motherhood is considering who she will be once the demands are rescinded, when the children are older. Who will she possibly be then?

Laurence’s The Diviners is so central to my literary consciousness, and I couldn’t help but see Stacey in the context of the Manawaka she’d fled from as a young woman, and in relation to Morag Gunn whom she’d stood apart from as a child but whom she’d have so much to talk about if they met up again in adulthood. And I was surprised to discover that Morag didn’t even exist when Laurence wrote The Fire Dwellers—The Diviners would be published 5 years later in 1974. But in The Fire Dwellers, you see the roots of The Diviners taking shape, its ideas and experiments with narrative and form.

Laurence’s The Diviners is so central to my literary consciousness, and I couldn’t help but see Stacey in the context of the Manawaka she’d fled from as a young woman, and in relation to Morag Gunn whom she’d stood apart from as a child but whom she’d have so much to talk about if they met up again in adulthood. And I was surprised to discover that Morag didn’t even exist when Laurence wrote The Fire Dwellers—The Diviners would be published 5 years later in 1974. But in The Fire Dwellers, you see the roots of The Diviners taking shape, its ideas and experiments with narrative and form.

Stacey MacAindra is Betty Draper, is calling out for Betty Friedan, though fat load of good a book is going to do her. (I always find it interesting when people critique Betty Draper’s character for her obviousness to Friedan, as though one day every woman in America read The Feminine Mystique, and society flicked a switch). Stacey MacAindra is also so many of us, as we remarked at my book club the other night. “Maybe we all turn into Stacey MacAindra sometime…” as I tweeted last week. Women for whom the day is never long enough to encompass all the things we want to do, all the people we want to or need to be. Women for whom motherhood and selfhood become a battle, with wifehood thrown in for good measure. You’d throw it all away, if you weren’t tied to it inextricably.

Stacey’s green slacks are dated, and so is her slang, but absolutely nothing else is in this novel which 45 years later is a challenge to and a reflection of the world at once.