January 17, 2017

Reconciling

The first definition of “reconcile” in the Merriam Webster is ” to restore to friendship or harmony <reconciled the factions>” but it’s the second definition that is more meaningful to me: “to make consistent or congruous <reconcile an ideal with reality>.” This definition certainly resonating in general, because in the past two months my ideals and reality have certainly been at odds, and reconciling that has been a process. The world is more complicated than I ever knew, which makes “restoring to friendship and harmony” seem like a pipe-dream, except: restoring, how? Because when was there ever friendship and harmony? It all sounds a bit like the notion of making America great again—elusive and facile. The first definition is a misnomer. Reconciliation is a process, and in order to be properly it is a process that will never end.

I’ve been thinking a lot about reconciliation lately, as I’ve been reading I’m Right and You’re an Idiot: The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean It Up. A friend of mine has also recommended Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair. I’m interested in and troubled by the way that people seem unable to constructively disagree with each other. (Another book along these lines that I’ve appreciated is Creative Condition: Replacing Critical Thinking With Creativity, by Patrick Finn.) I take some solace in the fact that people in disagreement, while inconvenient, is actually much healthier than the alternative, and that the potential for learning is infinite. A community in which everybody though the very same thing, and nobody challenged anyone or asked any questions, would be the very worst thing I could imagine. Worse even than the state we’re in now.

Remember my mantra for 2017, “Listen. Be Better.” I’m trying. It’s a challenge, and such an opportunity. Once upon a time, when I was young and things were simpler, I fervently underlined the following bit from Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, a play I loved: “This is the best time possible to be alive. When everything you know is wrong.” Such a prospect is more terrifying than I ever thought it would be, now that we’re kind of here and, you know, with the collapse of the world order, but still, there is something extraordinary about it too. I’m thinking about reconciliations big and small, in terms of domestic politics and literary criticism, even. Literary criticism, especially, because I wonder if this is a constructive metaphor with which to understand the process that has to happen in order for anything to happen.

Literary criticism, the best kind, is a conversation. A back-and-forth, a broadening, the prying of a text wide open. The best kind of literary criticism isn’t just about the text itself, but it’s about everything, and it invites big questions and many different answers. It provokes debate and causes the reader to change her mind—about the text, about the world. It’s not about whether a text is necessarily good or bad, but about the things it makes us think about, the places it takes its readers beyond itself. Literary criticism is a process, a collaborative ongoing pursuit which requires generosity, openness, consideration and respect on the part of the players involved. If no one’s listening, nothing happens, but if everyone is willing, anything can.

I was thinking about all this as I read Debbie Reese’s review of the award-winning picture book, Missing Nimama, which I reviewed in 2015—and you can read my review here. I am a huge admirer of Debbie Reese’s scholarship and advocacy about representations of Indigenous people in children’s books—she’s taught me a lot and she challenges my understanding in uncomfortable and constructive ways. She’s not afraid to go up against really popular authors—see her review of Raina Telgemeier’s Ghosts. I don’t always agree with her assessments of certain books, mostly because there are so many lenses through which readers approach a book, and hers is one, but I’ve never found her to be wrong.

While I still appreciate Missing Nimama and celebrate its success, Reese’s review shows me my own weaknesses in approaching it as a writer and a critic. Reese writes: “To me, however, Missing Nimama …. strike[s] me as something Canadians can wrap their arms around, to feel like they’re facing and acknowledging history, to feel like they’re reconciling with that history.” She continues, ” To many, this review…will feel harsh. Most people are likely to disagree with me. That’s par for the course, but I hope that other writers and editors and reviewers and readers and sponsors of writing contests will pause as they think about projects that involve ongoing violence upon Native women.”

And this is just the point. The pause, the reflection. Disagreeing is even okay, but it’s failing to consider that is inexcusable. The point is the conversation, the questions that are asked, which are far more important than the answers. And how we take these questions with us, this broadened perspective, with the books we read and the books we write. The point is to listen, and then be better.

UPDATE From Carleigh Baker’s review of Katherena Vermette’s The Break:“A generous storyteller, Vermette does not take it for granted that all readers will inherently understand how damaged the relationship between indigenous people and Canadian society has become. As readers, we can honour this generosity by not allowing ourselves to be lulled into a satisfying sense of camaraderie, having suffered alongside fictional characters. We can honour it by not repeating over and over how strong the women in this book are. It is true, they are strong. But let us not nod our heads in grim recognition of this strength, as if acknowledgement equals solidarity [emphasis mine]. Let us not pull our lips into thin lines and furrow our brows and express amazement at their resilience, as if its origin is a mystery. This makes it too easy to dismiss.”

January 12, 2017

Best Book of the Library Haul

There is a whole subset of nursery rhymes that I never learned as a child, although I did know my Rockabye Babies and Pat-A-Cakes, and was fairly literate in most respects. But it turned out what I knew was only just scratching the surface of the enormous richness and history that nursery rhymes offer, the bulk of which has been passed down through the annals of time by, well, (at least in my experience), librarians at the Toronto Public Library—could they really be responsible for preservation of this cultural trove? In addition to the Opies, of course. Rhymes like See, Saw, Sacredown and Leg Over Leg the Doggie Went to Dover. I discovered these at the Baby Time circles at the library after Harriet was born in 2009, which was same time I discovered Mem Fox.

There is a whole subset of nursery rhymes that I never learned as a child, although I did know my Rockabye Babies and Pat-A-Cakes, and was fairly literate in most respects. But it turned out what I knew was only just scratching the surface of the enormous richness and history that nursery rhymes offer, the bulk of which has been passed down through the annals of time by, well, (at least in my experience), librarians at the Toronto Public Library—could they really be responsible for preservation of this cultural trove? In addition to the Opies, of course. Rhymes like See, Saw, Sacredown and Leg Over Leg the Doggie Went to Dover. I discovered these at the Baby Time circles at the library after Harriet was born in 2009, which was same time I discovered Mem Fox.

Mem Fox, author of Ten Little Fingers and Ten Little Toes, Harriet You’ll Drive Me Wild, Hattie and the Fox, Time for Bed, and most spectacularly, Where is the Green Sheep, which were mostly the books I read more than any other through 2009-12. A passionate advocate of early literacy, Fox is also author of Reading Magic, a book that has been fundamental to my practice as a parent, and which recommended children get on a necessary diet of at least a handful of nursery rhymes every day. And because of the TPL Librarians, I had nursery rhymes to spare, so it was handy.

For parents who do not have a plethora of librarians at their disposal, however, Mem Fox comes to their aid with her picture book, Good Night, Sleep Tight, illustrated by Judy Horacek. Fox has taken age-old nursery rhymes (“It’s Raining, It’s Pouring,” “Round and Round the Garden,” This Little Piggie,” etc.) and linked them into a story featuring a rather dynamic babysitter called Skinny Doug whose mother must have been a TPL Librarian, because she’s taught him all the rhymes, which he’s now passing onto his babysitting charges, Bonnie and Ben. Who are definitely enjoying his performances—and not just because they’re delaying bedtime—because whenever he finishes another rhyme, this happens:

“‘We love it, we love it,’ said Bonnie and Ben. ‘How does it go? Will you say it again?'”

“‘Some other time,’ said Skinny Doug. ‘But I’ll tell you another. I heard it from my mother…'”

Which becomes, quite frankly, the most beloved rhyme in the whole book, so much so that when anything is regarded with great enthusiasm in our family, we take to chanting, “We love it, we love it, said Bonnie and Ben!!” in a way that’s a bit nonsensical. But then most nursery rhymes are.

We’ve had this book out of the library a million times, and it’s become such a part of our canon that I wanted to make sure that I wrote about it here. It’s a simple premise for a book, but it’s also quite profound, taking centuries-old rhymes and introducing them to new audiences—children, their parents from non-European cultures, or anyone who wasn’t lucky enough to learn these rhymes first time around. Through her story and Horacek’s illustrations, Fox conveys how these nursery rhyme works and how to use them, that this one book is not just one book but instead the product of generations’ cultural lore, ensuring literacy and a love of language for those who come after.

January 6, 2017

Rad Women Worldwide

Quite intentionally, I am raising my children in a house full of books, and while this has resulted in my children engaging with books a lot, best intentions don’t always lead where you’d like them to. I do have a theory that books can work by osmosis and that just being around them makes people smarter, and I cling to this belief when my oldest child passes up the incredible works of world-broadening non-fiction we have stocking our shelves in order to reread the Amulet series for the five-hundredth time. I had this vision of children sprawled on the carpet, leafing through our encyclopedia of animals, illustrated atlases or perusing the images from Sebastian Salgado’s Genesis. Sometimes I even intentionally leave these books on the floor, so as to instigate said leafing and perusing, but then the children just end up using these books as stools on which to perch while reading Amulet.

The book Rad Women Worldwide, by Kate Schatz and illustrated by Mariam Klein Stahl, might have joined this pile of books for sitting on. It was an extra Christmas gift, purchased without forethought. A good book to have around the house, I thought, particularly in these regressive times. Subtitled, “Artists and Athletes, Pirates and Punks, and Other Revolutionaries Who Shaped History,” by the creators of the brilliantly conceived American Women A-Z. It doesn’t hurt that the book’s design is awesome. I loved the idea of my girls learning about the incredible women profiled within, and understanding that their amazing accomplishments are what history is made of. We don’t even have to call it “herstory.” All this is simply the society in which we live.

Rad Women Worldwide includes women making history throughout history, but also women who are making history as I write this. And I love the idea of my children taking for granted not just that history includes women, but that history (and feminism) includes women of colour also—this is huge if I hope to raise white feminists who aren’t White Feminists (TM). I want to raise girls who see race and know race, acknowledging the role it plays in people’s lives (including their own). And I want them to know that the world and progress is powered by women who are black and brown and Asian, as well as white. I want my white children to grow up inspired by the accomplishments of women of colour—and with this book, how can they not be?

The thing about Rad Women Worldwide, though, is that it’s not just for children. It’s not only they who have gaps in their education, and the stories in this book are so fascinating that we’ve started reading them aloud. So that this isn’t a book just for sitting on, but also because I want to learn more about the women I’ve already heard of (Aung San Suu Kyi, Malala Yousafzai) and want to discover those I hadn’t heard of yet (Kalpana Chawla, the first Indian female astronaut, Junko Tabei, who was the first woman to climb Mount Everest, Fe Del Mundo from the Philippines who was the first woman admitted to the Harvard Medical School in 1936).

So we read a profile a day, Harriet and us taking alternate paragraphs, and I love the words that are entering her reading vocab: “Indigenous,” “Constitution,” “Advocacy,” “Reconciliation.” These stories are the perfect antidote to the bleakness that pervades news stories about women right now, riding the sad coattails of #ImWithHer. Inspiring, fascinating and ever-illuminating, each story affirms my faith in progress and justice just a little bit more.

December 15, 2016

Christmas Books

We’re winding down to the holidays (although, unfathomably, they don’t start until the end of next week when school’s out). Instead of Picture Book Friday, I want to point you toward my Instagram account where I’m sharing a title from our Christmas Book Box every day. We’re also reading the short novel A Christmas Card now, which our friend Sarah read last year (as we were reading The London Snow, by the same author, Paul Theroux). Today we walked home from school in a glorious blizzard, and hot chocolate with marshmallows are getting to be a habit.

December 2, 2016

The Day Santa Stopped Believing in Harold

I full-on believed in Santa Claus until I was eleven, mostly through sheer force of will and because I was a strange child, and I’ve actually kind of still believed in him ever since then. If asked if there is a Santa, I’ll never say one way or another, because there are some kinds of magic that are beyond our understanding. If asked if I in fact partake in performing the duties of Santa, I may concede that I do, but that such partaking is in fact part of the magic, but no one’s asked me that question yet. There have been other question though, and I will answer them carefully, recalling my own longing to believe that so preoccupied me as a child, a longing that had me actually making notes on the books I was reading and tallying those in which Santa was confirmed as real or otherwise within said books (and there became more of the latter, obviously, as I became actually eleven—I think I was actually reading Sidney Sheldon novels when I was eleven, although Santa rarely came up in these).

The Day Santa Stopped Believing in Harold, by Maureen Fergus (Buddy and Earl) and Cale Atkinson (If I Had a Gryphon) is definitely pro-Santa, and the perfect book contending with these sorts of questions who’s just not quite ready to give up yet. Santa, it seems, has stopped believing in a child called Harold, because the letters Harold writes to Santa are penned by Harold’s mother and Santa’s snack each Christmas Eve is actually catered by Harold’s father. Santa’s wife tries to convince him otherwise, but Santa will not be deterred, and resolves to wait up until Christmas morning so he can see Harold for himself and finally discover whether or not he actually exists…

I bought this one to commemorate the beginning of the Christmas season, a new title for our Christmas book box, and we absolutely loved it. It’s sweet, silly, and the perfect Christmas book for the savvy kid who wants to go on believing just a little bit longer.

November 25, 2016

How Do You Feel?

I’m going to say it—it’s been a rough few weeks. Yesterday I asked a parent in the school yard if he was American, intending to wish him a Happy Thanksgiving, and he looked so upset when I asked him. “I’m not accusing you of anything,” I said. “I’m just trying to create some distance from that mess,” he responded, and I got that. I’ve been trying to create some distance too. I took Twitter off my phone. Between conspiracy theories, white supremacy and CanLit ridiculousity, the platform has ceased to have much value except for to constantly have me exclaiming, “What that actual fuck?” I’ve tried telling men’s rights activists to eat various bags of dicks, and attempted to engage with a woman who insisted that the patriarchy wasn’t real (“That’s what they want you to think,” I told her, with a winky face, which she didn’t think was very funny, and my goodness, I thought feminists were the humourless ones) and watching what’s happening at Standing Rock just causes me to despair.

There are a whole lot of people on Twitter who, before November 8, I’d been in adamant disbelief that they were actually real. But it seems that they exist, human bots. Who refuse to read anything but Wikileaks emails, have eggs instead of heads (remember when once upon a time that implied intelligence?) and have no passion for anything except the things they hate. Which is anything the least bit challenging. And there is this atmosphere of disdain for feelings. Slinging “crybaby” like an epithet. This from people supporting a man whose supporters had been stockpiling arms for the event of their disappointment—and suddenly crying was something terrible? Speaking of alternate universes.

Who are they, the people who make fun of feelings. Do they not understand that it’s feelings that underline the dangerous fabric of nationalism? That there is nothing rational about screaming nonsensically at a rally, or screaming, “Kill the Bitch? (I am never going to forget that phrase.) That the notion of safety has become a joke. Why would denying others such a thing be the hill you’d choose to die on? And I keep getting emotional—of course I do. I feel terrible. I am sad, and angry, and frustrated, and disappointed. And really, really confused by the determination of others to put our precious, fragile, precarious arrangement in peril.

Pendulums swing though. And back. It’s the way of history. And it’s healthy to keep asking ourselves questions. “How do we keep what we believe in and know it’s right from becoming dogma?” I asked my friend May yesterday, and that’s a whole other blog post. We talked about how apparent injustices are now, all those things we were able to ignore before that have risen to the surface. To be acknowledged, looked in the face. Finally. It’s all very hard, but necessary. And in the meantime, the question of feelings are going to be more so. (See also this post: What are you going through?)

On Thursday I went to the Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards Gala, and drank all the wine, which helped a bit with the whole feelings thing. And in my silly bubble of happy, I felt grateful to be surrounded by people who acknowledged the power of books and of story and truth and history. We need books more than we’ve ever needed them, books to keep us asking questions, books to make sense of the madness, and to underline to our children the things that are important and ever shall be.

Harriet remains a hedgehog fanatic, and therefore we have all become fond of the book, How Do You Feel?, by Rebecca Bender. I love the double meaning of the question (because anything that teaches that a single thing can have two realities is important), and that the answers to the questions are all about words and similes. The whole book is about connection, and it’s sweet and lovely, and also powerfully subversive in the most important way.

November 18, 2016

Missing Nimama

Congratulations to Melanie Florence and Francois Thisdale, whose hauntingly beautiful picture book, Missing Nimama, about a murdered Indigenous woman won the TD Children’s Book Prize last night at The Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards. This book is an extraordinary demonstration of what the picture book can be and do; you can read my review here. I’m also thrilled for Danielle Daniel who won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Prize for Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, another book we’re big fans of at our house.

A complete list of winners is here. It was a terrific night.

November 11, 2016

We All Count.

Turning to books for comfort and wisdom this week. This gorgeous title is one of my favourites. At our play school’s blog, I’ve made a list called Picture Books for a Better World, of which We All Count is a part.

October 28, 2016

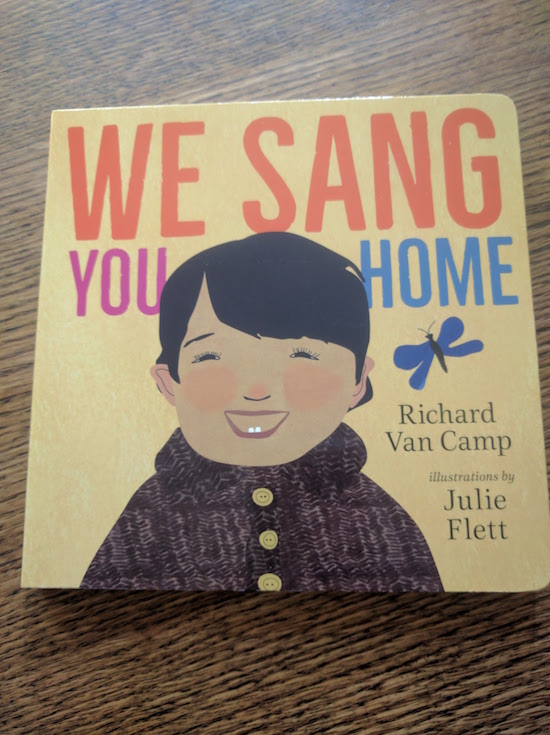

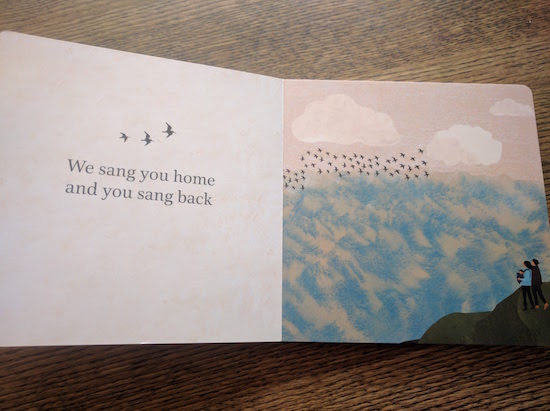

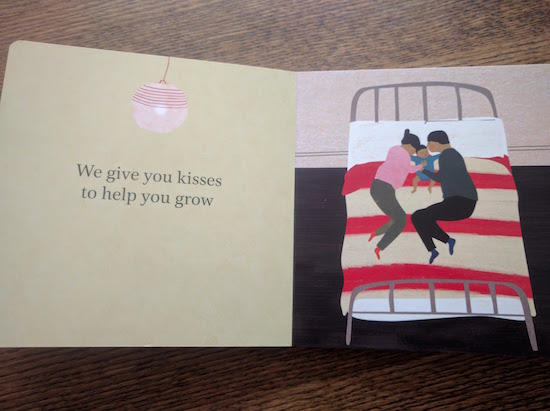

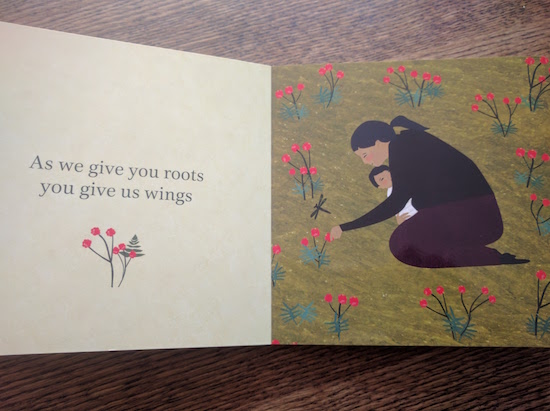

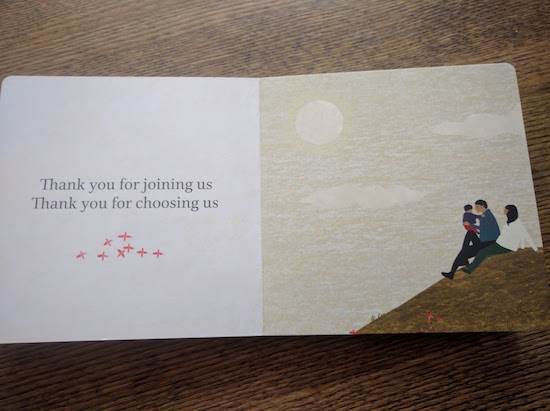

We Sang You Home, by Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett

You might recall that back when Iris was the world’s most disagreeable baby, the only book that held her interest was Little You, by Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett. It was a book that was so lovely I actually made the words into a lullaby, and the illustrations were so delightful that we got lost in them (the hole in the toe of the mother’s tights!), and we would have loved it so much anyway even if we hadn’t bowed down to it in gratitude for its suggestion to us that Iris was actually capable of liking things, and that she had superior literary taste even.

And so naturally, we’ve been excited about Flett and Van Camp teaming up again on another board book, even if my children (gulp) are beyond board books. Even if this is a technically another “Welcome, Baby!” book, and we haven’t welcomed a baby in three-and-a-half years. We are Richard Van Camp/Julie Flett mega-fans, and so we snagged a copy of We Sang You Home as soon as it dropped in our local shop. (We saw it in the window, but it was Sunday, and the store was closed. So we went back first thing the very next day!)

“Thank you for coming to live with us,” is a thing I like to say to my children, because I mean it profoundly, even if I do not entirely understand what I am talking about. (“Where did you live before you were born?” I ask Iris. “That was when I was dead,” she answers.) The chance, the luck, the miracle, of these two extraordinary people being created and born and raised to now is something that stuns me every time I think about it. I feel like a passive agent in the whole scenario too—for whom am I to take credit for orchestrating pure magic? I was just a body along for the ride.

In We Sang You Home, Van Camp gives credit where credit is due, giving thanks to our children with blessing us with their lives, and enriching our worlds with their presence. The best thing about the book is its lack of specificity in both prose and illustrations as to how these babies actually got here—this story is suitable for adoption, same-sex families too. It gets at the point that is always universal—that when a child arrives, a parent is born, and the world is never the same.

October 21, 2016

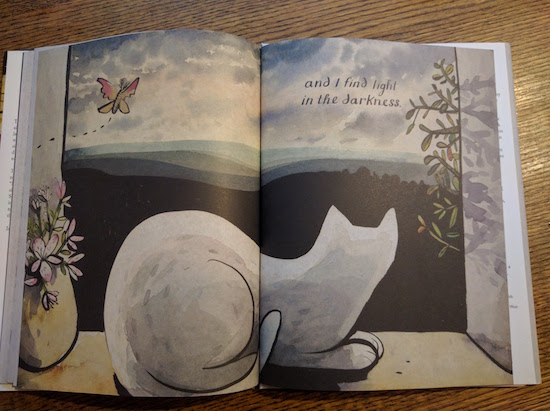

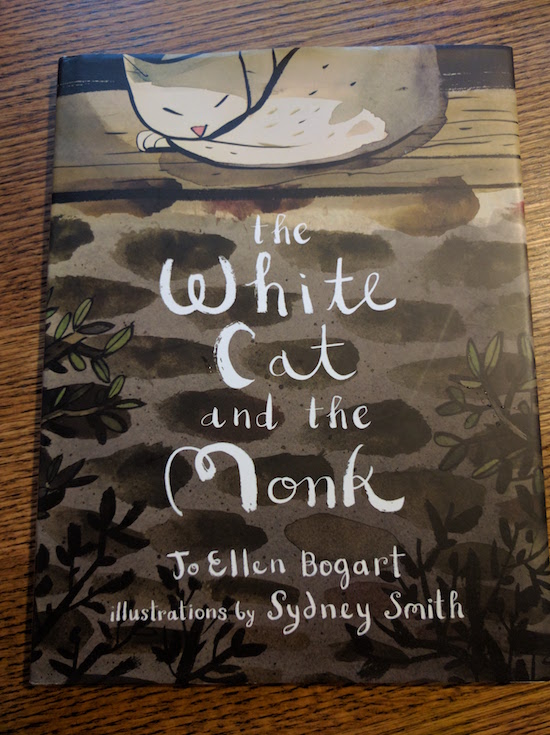

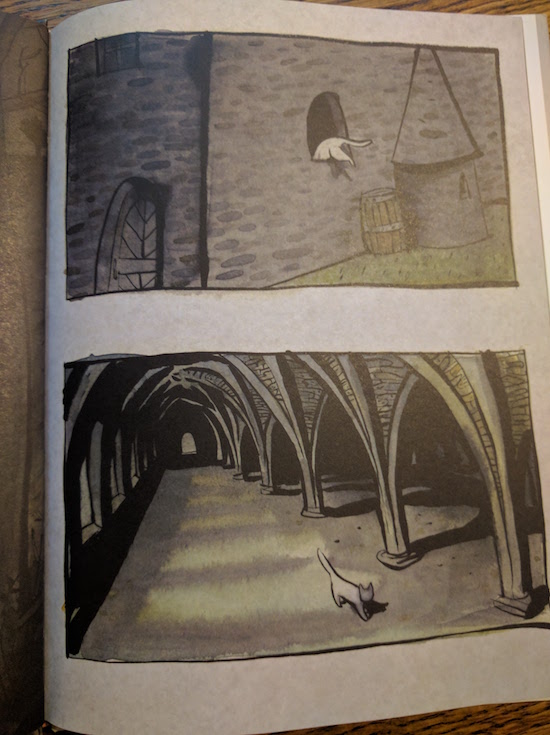

The White Cat and the Monk, by Jo Ellen Bogart and Sydney Smith

Of the many ways in which picture books are superior to all other literary forms is that it’s implicit that the book is going to be read at least one hundred times. You don’t even have to try, it just happens. “Read this one,” says a little voice as little hands force the volume into yours. Again. There are the books on the shelf that get picked up all the time, and even those which aren’t as regularly selected turn up often as a kind of diversion.

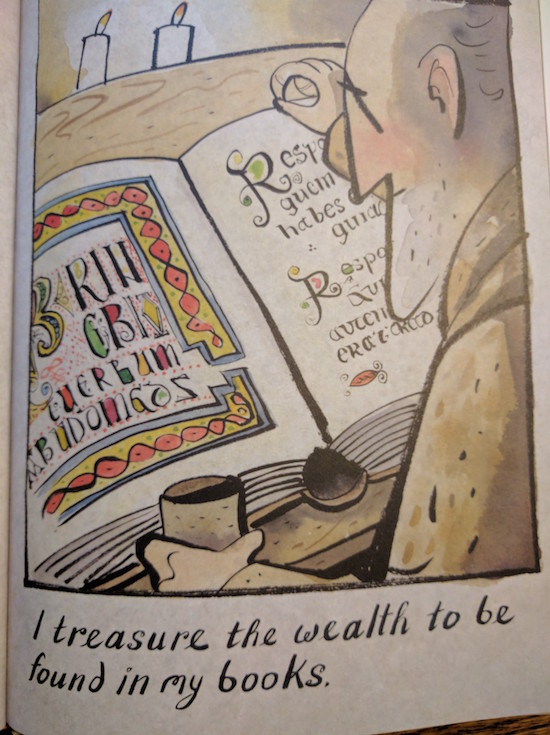

The White Cat and the Monk, by Jo Ellen Bogart, illustrated by Sydney Smith, came out in the spring, and we’ve been finding our way deeper and deeper into it with every read. It’s effect is subtle, at first. It’s a simple story based on a poem written more than 1000 years ago by an Irish monk whose name was never recorded. As Jo Ellen Bogart explains in her Author’s Note, the poem, called “Pangur Ban,” has been translated many times throughout the ages, and the words she’s selected for this incarnation are inspired by a number of these.

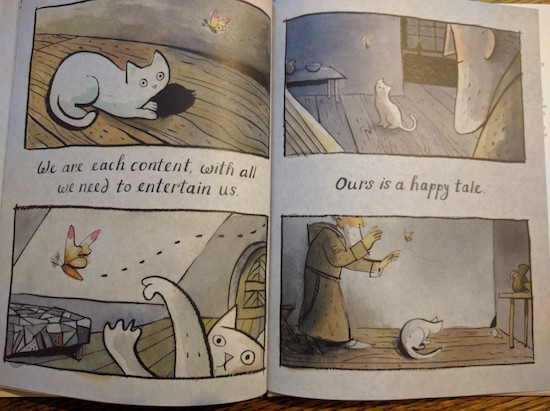

The story is about a monk who spends his days and nights seeking wisdom in the pages of his books, and who identifies with a white cat that has made itself his companion. Quietly, the two together go about their own particular trades, the cat pursuing its mouse and the monk pursuing knowledge.

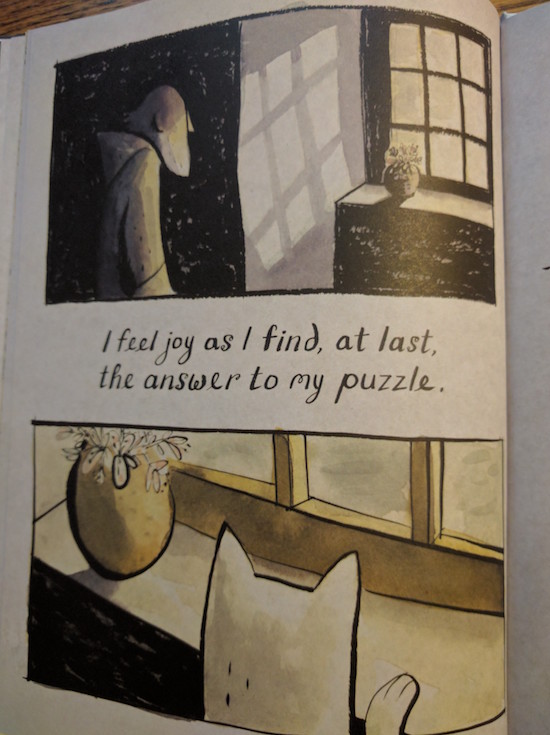

I don’t completely understand the story—that’s why I like reading it so much, getting a better sense of it every time. Is the scholar like a hunter? Is knowledge like prey? And what of the poor mouse? Not such a happy tale for him. It’s a book that raises questions—not surprising for a story based on an anonymous text. And that’s the very point, I think, the reader’s experience analogous with the scholar’s and even the cat’s.

Notions of predator and prey are complicated by an additional layer of meaning offered through Sydney Smith’s gorgeous illustrations with the appearance of a butterfly in the room. The cat swats at it, watching it…and the monk opens the window to set the creature free in the story’s final spread and beautiful last line of text.

And I’m still not sure what the butterfly means, but I trust that in another hundred reads I’ll probably have a good idea.