April 7, 2017

A Horse Named Steve, by Kelly Collier

Is there room in Canadian literature for another equine creature who’s got a couple of quirks? Which is to say, if you have a thing for roly-poly ponies, do you actually need a horse named Steve?

But you do! Because it turns out that A Horse Named Steve is a genus all onto itself.

The debut picture book by Kelly Collier, A Horse Name Steve (published by KidsCan Press, which just won North American Publisher of the Year at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair) is a fun, comics-inspired tale of an ordinary horse who wants to be exceptional. When he finds a gold horn lying around (as you do) he imagines an exceptional life lies before him now, but then when he gallops off to show the golden horn to his friends, things go ever so slightly…askew.

With the horn out of place, Steve’s colleague, Bob the Racoon, reports to him, “I don’t see a beautiful gold horn on your head. You are not exceptional.” Which comes as a shock, and poor Steve cries so hard he gets thirsty, and when he goes to get a drink, our little pseudo-Narcissist sees in his reflection that the gold horn is right there after all. It’s no use though, because horses are not so dextrous in this respect, and when he goes to fix his horn, Steve ends up falling in the water. “Poor Steve. He is hornless and drenched.”

The tragedy that has befallen him has a positive outcome though—turns out that Steve’s horn has started a thing-on-the-head mania amongst the forest creatures, and when he falls in the water and his horn gets lost…suddenly Steve is exceptional again. Turns out bare heads are where it’s at after all—”I love the natural look he’s got going,” says the rabbit, the other animals agreeing, “Very stylish. How does he do it?”

Surely there are lessons contained within about the importance of accepting one’s self, being an individual, blazing a path instead of following a path, etc. But the great charm of this book is that these ideas exist deep in the background while A Horse Named Steve manages to be exceptional in its own right—the simple drawings, the humour, the chatty asides that make reading the book aloud an absolute delight.

March 31, 2017

The Everywhere Bear, by Julia Donaldson and Rebecca Cobb

My favourite Julia Donaldson is Julia Donaldson with Rebecca Cobb in The Paperdolls (even if I do have to add in that the little girl in the book grew up to become a particle physicist, a politician and an opera singer, as well as “a mother,” because let’s remind our children that a person can be very well rounded), so I was delighted to see their latest collaboration, The Everywhere Bear. Ticky and Tacky and Jackie the Backie don’t make an appearance, but we’ve got Ollie and Holly and Josie and Jay, Leo and Theo and April and May, etc. etc. All members of a classroom whose class bear comes along with the children on various adventures, but then one weekend things go amiss the bear gets lost, embarking on a remarkable journey of his home that will bring him home again. “Hooray! Hooray!” cheer my children at the end of books like these. “Nobody dies!” They will not tolerate an unhappy ending—even the paper dolls’ snipped up fate makes them a bit uneasy, but we all love this one, Donaldson’s bouncy rhyme and Cobb’s adorable round faces. A keeper for sure.

March 24, 2017

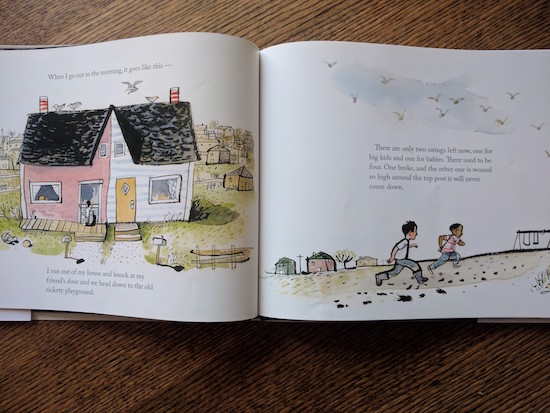

Town is by the Sea, by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith

Never has a book so literally sparkled like Town is by the Sea, a new collaboration by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith. In the story, Schwartz draws on her own Cape Breton background to tell the story of a day in the life of a coal mining town, about the life that goes on up above while the men are working down below.

And in a book about contrasts, illustrator Smith pulls off a similar feat. As his early books (reissues of Sheree Fitch’s classics are where we first saw his work!) were fun and cartoonish, that same sensibility charges many of the images in this book—illustrations of domestic life and children at play. (He also exhibits a fixation on teacups that won this book a firm place in my heart.) But the teacups aren’t all of it—just wait for a moment.

Because first we see the men going down into the mines to work. (My children are fascinated by this. “What is coal?” Iris asks us, which is weird because usually she manages to parse out meanings, is rarely moved to ask about something so explicitly.)

“When I wake up, it goes like this—” Schwartz’s story starts, and this pattern sets up the way that the boy in the book will tell his story. First he hears seagulls, and then a dog barks. “And along the road, lupines and Queen Anne’s lace rustle in the wind…”

“And deep down under that sea, my father is digging for coal.”

And now here it is, that sea. A sea so sparkling that it appears animated, an image that would not look out of place in a museum. Hasn’t it got a bit of the Monet about it? Otherworldly. Which is fitting.

Meanwhile, the boy plays with his friends, he walks through town. He goes home for lunch, then goes back out again. The sea is perpetually present, and its evocation brings us back to the men in the mines. “And deep down under that sea, my father is digging for coal,” and my children read along with the refrain. But the last time we see the men, something is different.

The text doesn’t allude to the image of the men escaping some kind of collapse underground, and the sing-song story goes along, but what happens next in the illustrations takes on a particular subtext, a wordless story like the one Smith tells in JonArno Lawson’s award-winning Sidewalk Flowers*. The boy goes to visit his grandfather’s gravestone, his grandfather who was a miner just like his father, and who made sure that he’d be buried facing the sea because he’d spent enough time underground. “I go to the graveyard to visit my grandfather, my father’s father. He was a miner too. The air smells like salt. I can taste it on my tongue.”

The trouble underground and the imagery of death will make for some uneasy for reading for those of us who know the dangers of coal mining, who’ve heard the stories of disasters. But alas, that is a story for another day. In this book, the boy’s father comes home. Danger and peril, and it’s still just an ordinary day.

“One day it will be my turn,” the boy tells us, about the men who go down below to mine for coal. “I’m a miner’s son. In my town, that’s the way it goes.”

*Full credit goes to my husband Stuart who is much better at reading picture books than I am. It took me ages to figure out that the bear had eaten the rabbit in I Want My Hat Back, or what was different at the end of Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. I might have read this book a hundred more times without realize the enormity of what’s really going on beneath the surface (see what I did there?) so I am glad that I keep someone very clever around.

March 17, 2017

You Are Three, by Sara O’Leary and Karen Klassen

Three is a good age, is a thing that someone said to me today, and it might have been the first time I ever heard that. I cocked my head. “Oh, really?” Although she was talking about her grandchild and maybe three is a good age if the child is only yours on a partial basis. For the rest of us though, three is a battle. Three is ferocious, still wakes you up at night and no longer naps. Three has more complex needs, and will still bite you in a pinch. Three is strong and tenacious and refuses to give in, and can whine and whine until the sun goes down. And keep on whining.

And yet. Three is also sturdy legs that can walk long distances with no complaints. Yes, three will point to your stomach and remind you that you look like you’re having a baby, but three will also whisper in your ear that you look like a princess. You never even knew you desired to look like a princess, but you are satisfied. Three tells stories about her friends at school, and eats everything in her lunchbox even though she never eats at home. She loves cats, but only if they are pink. Three likes to read chapter books because her big sister reads chapter books, and she picks sparkly ones out at the library with fairies on the cover, and she sits alone thumbing the pictureless pages and you wonder what she sees.

So yes, three has been a good year, even though three is hard and stubborn and still screams when you are unable to conjure impossible things. Three will howl for blocks and blocks or run away from you in a crowded subway station just to demonstrate how much she doesn’t want to hold your hand. But three will also sit at the table, most of the time. She will tell jokes and contribute to discussions and ask questions and point out things you never would have noticed on your own. With a three-year-old, you are a family, instead of three people and a baby. Your seven-year-old will say to you, “It’s really great to have a sister you can talk to.” And you will only be partially totally confused about what exactly she means.

(My favourite thing in the world is listening to my three-year-old singing along to songs that my seven-year-old is making up on the spot.)

Three is a good age, because it means we no longer have a baby. We never wanted another another baby after we had our last one, and I don’t lament the end of the baby years. My baby is heading off to kindergarten in the fall and I am fine with that. This is why we had babies anyway; the babies were what we had to go through to get the kids. And we love the kids. We toss the baby stuff out to the curb and cheer, and have filled all that space with camping equipment.

And so I was surprised to be moved by You Are Three, the final book in Sara O’Leary and Karen Klaassen’s trilogy celebrating the milestones of toddlerhood. Flipping through the pages the other night, I felt a bit emotional. Because three is a cusp, about to unfurl. Three is a person’s threshold to the world, and while I’m ready to usher my little person through the door, it’s easy to forget the moment we’re in. This funny girl will never again be so funny, or at least not funny in the same way. The You Are Three book reminds us to notice where we are right now: the kid who rides a scooter, carries her umbrella, and loves to hide. Her incredible worlds of make-believe, and her pictures, and the ways she sings her ABCs. “You are still our baby/ but you are also your own person./ We love to hold you close/ and we love to watch you run.”

March 15, 2017

Revisiting Booky

Harriet and her Brownie group served dinner to a group of homeless and impoverished young people at a local church a few weeks ago, which taught us an essential truth about the face of poverty, which is that it has many faces, people with all kinds of different stories, and people with children and babies. None of the girls could quite get over that—that there had been a baby. Though of course it was the baby’s table everyone wanted to serve at, but even the people who weren’t babies were really nice and everyone was friendly and polite. And then we came home and picked up another chapter of That Scatterbrain Booky, by Bernice Thurman Hunter, a novel we’d been reading together over the past few weeks.

Hunter’s Booky series and her Margaret books had been huge for me growing up, as both a reader and a writer, although until I picked the novel up again and realized how much the stories were now built into my literary DNA, I hadn’t given them that much credit. The series is not exactly unsung—a Booky film was made starring Meaghan Follows about ten years ago, titles are still in print—but there were no copies for sale in the bookstore I was in the other day. And you don’t hear writers talking about Booky, the same way they talk about Anne or Emily, or Alice or even Harriet and Ramona—although a few years back Carrie Snyder included the Booky books on a list of titles that inspired her as a young writer.

One Saturday night though, so happy to be rereading the book and impressed to find that it was such a strong and powerful literary work (which is a thing you discover quickly when you’re reading out loud) I posted a photo of the cover on Instagram. And then my Instagram feed went bonkers. Everyone remembered Booky. Everyone loved Booky. Grown men professing their love for the Booky books and memories of Hunter visiting their school libraries in the 1980s. Everyone had Booky memories to share, the vivid scenes still resonant. There’s something about these books, and all its avid readers should look into revisiting them as an adult.

Because they’re really good. This incredibly strong but chatty first-person narrator who pulls in close and focuses on details (the warmth from the stove on the streetcar as passenger huddled around it, the stripes on the sweaters from the Toronto Star Christmas boxes which the kid who wore them got mocked for, the exact contents of a bag of penny candy) but then pulls out too with a broader perspective (“grandpa would only live three years after that…”) and shows the reader that these are stories told with the benefit of hindsight. The deftness with which Hunter maneuvered this was so impressive, but so too is the story’s gritty edges, which never detract from its buoyant tone. In fact as a young reader I never noticed, but they’re there. Booky’s family can barely support the children they have and (although nobody knows yet) another’s on the way, and she overhears her parents discussing the possibility of her parents giving this baby up for adoption. Strung across the entrance to High Park is a sign announcing that the park is “Gentiles Only.” When Booky’s dad finally finds work as a maintenance man at the chocolate factory, it’s only after the previous holder of that titled has been fatally injured in an industrial accident. Throughout the entire book, the family is this close to being evicted and at one point they actually are. And although the fact of it is breezed by, Booky is severely malnourished and therefore eligible for free milk at school. When her family sits down together at the table, often her parents eat nothing.

So this is far from the Old Toronto nostalgic days-gone-by kinds of stories I remembered Booky for, the kinds of stories Kamal Al Solaylee warned us about in his essay “What You Don’t See When You Look Back.” Although like those sepia-toned images, there aren’t people of colour in Booky’s stories, but they are just outside the frame. And the bygone days are not made sweet in their memory—these were hard times, and people suffered mercilessly. In the ways that so many still do.

By which I mean that when we read Booky the night after serving dinner at the church, the bygone days didn’t seem so bygone after all.

March 10, 2017

Under the Umbrella, by Catherine Buquet and Marion Arbona

A beautifully illustrated picture book that celebrates a few of my favourite things, namely light, umbrellas, and baked goods? Yes, please.

This week’s pick is Under the Umbrella, by Catherine Buquet and Governor General’s Award-winning illustrator Marion Arbona, translated by Erin Woods. As we turn towards the season in which the rain can seem unceasing and the world still a bit too cold and grim, it becomes important to be reminded not to hurry too much, and not to miss those moments in which light and communion is possible.

The book begins with a man who’s doing battle with the wind and rain, barrelling his way along his journey, and furious at the crowds and the weather, and everything that’s offering resistance. We follow along with him in rhyming verse: “The wind attacked. He bent his back/ and forced his way along./ Wet and cold and late—what else/ could possibly go wrong?”

The man doesn’t even notice the boy he passes staring into the window of the bakeshop. “Dry beneath the awning,/ he gazed upon the spreads/ Of cakes and creams and cookies/ meant to turn each passing head.” And what follows is a delicious golden spread that’s entrancing, a torrent of dancing baked goods…

When a gust of wind rips the umbrella away from the hurrying man’s clutches, the flyaway object lands at the little boy’s feet. The boy retrieves it and the man offers his thanks, and suddenly notices the world around him, the light at the window, the good things on display inside. “Aren’t they amazing?” the boy asks him.

I’m going to spoil the ending: the man goes inside and buys the wide-eyed boy a rhubarb-raspberry tart. (Like most things with rhubarb, I assume it’s made palatable with a great deal of sugar: yum.) And when the man delivers this delicious treat, the boy breaks it in half and shares it. Possibly he knows that shared baked goods have no calories…

“Under the umbrella, time seemed to stall. The rain fell on…/ The sky hung low…/The crowds crept by…/ And none of that mattered at all.”

March 3, 2017

Little Blue Chair, by Cary Fagan and Madeline Kloepper

Little Blue Chair, by Cary Fagan and Madeline Kloepper, is the kind of book you finishe reading with your family, and then there’s a split-second of silence which will be broken by someone saying, “That was a good one.” Everybody’s nodding.” It’s a familiar story, the kind we’ve read so many times before, but it’s just so deftly executed that you’ve got to admire it. And there’s plenty else to admire about it besides that.

It’s a something-from-nothing circle-of-life tale, and at its centre is a chair. A little chair, the kind you must contort your body into if you’re visiting a preschool, but this chair belongs to Boo and it’s the seat of his imagination. Fagan shows him using it to read, to build forts, to climb on, and he even falls asleep on it. (He sits on it too.) When Boo outgrows his chair, his mom puts it out on the lawn with a sign that says, “Please take me,” and therein because a most excellent adventure.

Do you ever wonder what happens to the things you put out at the end of your driveway? We’ve gotten rid of an antique bed frame, a busted stroller, a repulsive carpet, a trundle bed, a futon frame, a decapitated rocking horse, and several other objects that way. Moreover our coffee table, desk chair, and many other items in our household joined us in a similar fashion. After reading The Little Blue Chair, I’ll never imagine an item’s narrative trajectory from curbside as anything normal again.

A rattling old pick-up comes by and picks up (of course) Book’s chair, and the drive sells it to a junk shop. A woman buys it and uses the chair to sit her plant pot, but then the plant grows up, she plants it in the ground, and doesn’t need it anymore. And so back out to the curb it goes, where it gets picked up by a sea captain who uses it to have his daughter sit beside him as they sail across the ocean. When they’re finished with their journeys, the leave the chair on the beach, where a man finds it and uses it to give children rides on elephants.

And so on and so on, the most extraordinary travels, through the postal system and up a tree, and round and round on a ferris wheel (and oh, I cringed a bit thinking of the lax safety standards that might make that possible. I’d probably find a different place to sit if that were me…).

And on it goes, another child finding it and using it as the seat of his imaginative adventures, but then there is a misadventure involving balloons and one thing leads to another.

You might be able to imagine what happen next. Somebody finds the chair, and it’s a grown man who’s name is Boo, and even though the chair has been painted he can see where the paint has chipped and he can tell that this little chair is familiar. And quite conveniently, Book has a little person of his own at home for whom the little chair is precisely the right size, and she declares it perfect.

February 9, 2017

Ada Lovelace: Poet of Science, by Diane Stanley and Jessie Hartland

Harriet and I went to see the remarkable Hidden Figures on the weekend, and until the picture book version of the story is released, we will content ourselves with Ada Lovelace, Poet of Science: The First Computer Programmer, by Diane Stanley, illustrated by Jessie Hartland, which was recently selected by the America Library Association among the top ten feminist picture books of last year. (We also know Ada Byron [later Lovelace] as a character from Canadian author Jordan Stratford’s middle-grade series, The Wollstonecraft Detective Agency.)

True confession: I don’t understand computer programming. It’s possible that a lifetime of being told that math is hard made me believe that math is hard, or maybe I just find math hard, but my mind doesn’t work that way. I’ve read Ada Lovelace: Poet of Science several times, and while I understand in theory how Ada imagined Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine worked based on symbols and rules of operation changed into digital form…I actually don’t even understand it in theory. Ada Lovelace’s ideas were inspired by mechanical looms which wove textiles based on patterns dictated by punched cards. I don’t really understand that either.

But but but. There is more than one way to be a person, to be a woman, to have a brain. That such things befuddle me is not to say that women are like that and let’s all go back to rocking babies, but instead to say that some women have an aptitude for such things, and it’s useful for even those of us who don’t to realize this. It’s like saying, Maybe I don’t need feminism, but some women do. (Nobody ever says this though. People who don’t need feminism seem to forget the possibility of second clauses.) To be honest, I’m not sure my daughter is going to grow up to be a computer programmer either, genes being what they are, but I will insist on the fact that she knows it’s a possibility. I mean, if a girl could have been one two hundred years ago, before there were even actual computers, then maybe today there are perhaps no limits of what a girl can grow up to be. And isn’t that excellent?

We love this book, about Ada (who gives Rosie Revere, Engineer a run for her money) who has a spectacular imagination, despite her mother’s attempts to school her in logic and rational thinking in order to override her passionate poet father’s genetic legacy. As women of her station had to do, she settled down and married, but that wasn’t the end of her story, and she would go on to do remarkable things in her too short life, indeed becoming the world’s first computer programmer with Babbage’s analytical machine. And what is especially interesting is that there is no direct link between Babbage’s and Lovelace’s work and the development of modern computers, although as Stanley’s author’s note points out, Alan Turing would read their work after they resurfaced after a century of obscurity. But still, I am fascinated by this idea (which is so recurrent in feminism) that some ideas have to be invented over and over again. Or perhaps it’s more miraculous than that—that the great discoveries don’t just happen once, and that progress ain’t a line, but that spectacular bursts of excellence are exploding all the time.

February 3, 2017

My Beautiful Birds, by Suzanne Del Rizzo

As weird and terrible as the world can be, I don’t spend a lot of time, as the modern problem goes, worrying about “how I’m going to explain it to my children.” As I’ve written before, I relish awkward conversations. But I was thinking about this idea yesterday, about how incongruous it must be to be both a parent and somebody who wants to see refugees restricted from finding sanctuary in their country and community. What do these people teach their children about helping others, I wonder. Do they ever worry about the gap between their messages?

“As a parent,” somebody told me on Twitter this week, “my job is to protect my children from danger.” Hence their support of UnpopularDonald’s Muslim Ban. And the logical next question, although I didn’t ask it because this was Twitter and there was really no point, is “Isn’t that precisely what so many refugee families are doing though? And so surely as a parent then, you can recognize the humanity in these people, that they are guided by the same impulses that direct you, except that their homes have been destroyed by years and years of war and your fear is based on a sense of otherness and is also statistically irrational?”

The first time I was happy after November 9 2016 was a few weeks later at the Canadian Children’s Book Awards, and not just because I’d had more than a few glasses of wine. But it was because of the spirit that night, the speeches of the presenters and winners that acknowledged the darkness of the moment we’re currently embroiled in and that books really were one sure way to kick at the darkness, children’s books in particular. Books that bridge the distance between here and there, between us and them, and recognize the humanity common to all of us.

In Suzanne Del Rizzo’s picture book, My Beautiful Birds, a young Syrian boy is forced to leave his wartorn home and make the long journey to the relative safety of a refugee camp. The story is enlivened by Del Rizzo’s plasticine illustrations with their rich purple and golden hues. Of all the things that Sami has left behind. it’s his pigeons he misses the most, the birds he fed and kept and as pets. Although his family does their best to create a home in the camp—planting a garden, buying things in the small shops started by their neighbours—this new life is anything but sure: “Days blur together in a gritty haze. All I have left are questions. What will we do? How long will we be here?” The idea of the birds and their freedom symbolizing everything that’s been lost to Sami.

Del Rizzo shows Sami’s grief and sadness with thick black lines that overwhelm the pictures he tries to paint of his beloved birds, the black paint taking over his art like a storm. Where he finds solace, though, is in the sky, one thing that is familiar to him, “wait[ing] like a loyal friend for me to remember.” In the clouds, he sees the shapes of his birds: “Spiralling. Soaring. Sharing the sky.”

January 27, 2017

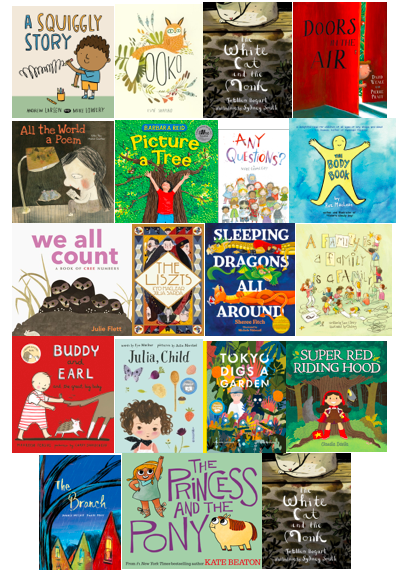

Picture Book Wisdom

It’s Family Literacy Day today, and I’ve written a post at 49thShelf about how everything I know about the world I’ve learned from picture books. Including, “Dance in the kitchen. Don’t do the dishes” and “Far more than any fame, enjoy the peaceful pursuit of knowledge. Treasure the wealth to be found in your books.”

You can read all the words of wisdom here, and make sure you pick up these great titles if you haven’t already.