June 16, 2017

By the Time You Read This, by Jennifer Lanthier and Patricia Storms

I love By The Time You Read This, the new picture book by Jennifer Lanthier (of the award-winning The Stamp Collector) and illustrated by my friend, Patricia Storms. It’s a story about two friends who’ve had a falling-out, and the wronged party is eager to rid his life of any sign the friendship ever happened, and so he’s taking down their fort, throwing out their stuff, shutting down their zoo, and ending their novel for good.

“By the time you read this,” he writes, “I will have forgotten we were ever friends.” Very dramatic, yes, but it also demonstrates the force (and complicatedness) of a child’s feelings toward relationships, and this force creates serious momentum too as narrator moves through the story with firm determination.

The story also demonstrates the incredible richness of a child’s imaginary world, which is only enlivened when shared with a friend, and this reader glimpses here the subtext of this, in how much is lost to the child when the friendship is. The blanket fort which is “our Indestructible Fortress of Fiendishness” and the collection of ordinary pets and stuffed toys which have been transformed into “our Magical Zoo of Mystical Creatures” with the wonder of play.

Having dismantled all evidence of the friendship indoors, the narrator heads outside via “our Precarious Portal for Intrepid Explorers” (i.e. the elevator—and how excellent that the story takes place amongst friends who live in an apartment or condo dwelling) and sulks on the playground contemplating just how he has been wronged, and it’s here we learn just how the misunderstanding between friends came about.

As you can glimpse from the illustration about, the two friends do reconcile, as friends often do—a very good thing to have affirmed. And by the end of the book they’re off on another big adventure.

June 9, 2017

The Thing That Lou Couldn’t Do, by Ashley Spires

If life were a movie, all persistence would lead to triumph. Adversity only would exist in order to be overcome. We would all be Rocky, champions, eye of the tiger. If you just try hard enough, success will inevitably result. And it’s not just movies—it’s books too, memoir and fiction, books for all ages. Stella gets her groove back. It leads you to believe that this actually happens, all the time. And for some people, maybe this is true.

Sometimes I feel like there should be a different kind of genetic testing before two people are allowed to procreate. Oh, wait a minute. You can map your entire childhood from the scars on your face from your struggles with gravity, and you played softball for four years and never ever once managed to catch the ball? Do you really think this is such a good idea? Maybe you both should adopt a ferret instead?

There will be a time when my child’s inability to do a cartwheel won’t really matter. (There might also one day be a time when she can do a cartwheel, but I am not holding my breath.) She couldn’t jump until she was four years old, and hopping remains a challenge. Jump Rope For Heart is coming up next week and she can’t do it. Mostly for lack of trying, it’s true, and if I could go back in time I would have enrolled her in gymnastics when she was two and given her a foundation in physical literacy, but I figured it was the kind of thing she’d pick up on her own. Like riding a bike. Which she still can’t do.

It’s not all failure, of course. I write here all the time about the magnificence of my children, their incredible imaginations and intelligence and how they are funny, kind of empathetic. They love exploring, can walk for miles, can make a game out of anything, read boatloads of books, are up for adventures, do well in school, get along with their friends, and are already very good members of their community. I admire them both immensely. But the whole story includes the struggles, and we’ve got plenty of those. Motor skills are not our forte. If I wanted to, I was told, I could pursue therapies with a aplomb and really nip this problem in the bud…or I could write my child off as a person a bit lacking in physical prowess. Something we both actually have in common. She’s kind of fine with that.

While bike riding remains elusive, she has mastered her two wheeled scooter, which isn’t easy to do. She still can’t skip (three consecutive jumps are a challenge) but we’ve finagled a slow-motion step thing with the skipping rope which might turn into actual skipping with practice. With a lot of determination, she learned to ice skate, and while she’s cautious and slower than her fearless friends, she can skate enough to have an acceptable Canadian childhood. And our latest and greatest triumph is swimming, even though she’s likely to repeat Swim Kids 2 again, but this is probably the last time, and she can actually swim now, which is a long long way for someone who has the buoyancy of a anchor. She’s had a good teacher this term who has pushed her, which she said she resented in the beginning, but she gets it now. On the chalkboard in our hallway, we’ve written, WE CAN DO HARD THINGS.

At their last physical exam, or maybe the one before it, I mentioned the challenge with physical things, and our doctor (who is the mother of four children and knows a few things) told me two things that struck me as quite profound. First, that when our brains have to work harder in order to respond to challenges, our brains get smarter. Struggle is good for us. And second, struggle can make us better people, people with more empathy towards those with their own struggles, a healthy awareness that everybody is fighting their own battle.

I love The Thing That Lou Couldn’t Do, by Ashley Spires, because (SPOILERS) she never learns to do it. This is not a story about triumph over adversity, but about adversity. About how adversity can be its own story, worthwhile in its own right. That learning and trying and trying again, regardless of what happens next, is its own kind of adventure. And that all of us are doing this in some part of our lives, and if we’re not, it’s only because we’re not brave enough to bother.

June 2, 2017

Up, by Susan Hughes and Ashley Barron

I don’t know where spring went. It was March and then ten minutes later it was June, which means we’ve just a few weeks left of playschool. Playschool, which has been so important to our family since Harriet began in 2012. Playschool, which has begotten us crafts and friends and songs and dances, and books, and where we’ve all learned so much, because being part of a co-op brings lessons for everyone. Very good lessons, about working with other people, and learning from their strengths, and what all of us can learn from each other.

When I bought the book Up: How Families Around the World Carry Their Little Ones, by Susan Hughes and Ashley Barron, I had it in my mind as a gift for playschool. Not just because the idea of carrying babies and playschool going hand-in-hand for me, as Iris spent much of her first year of life on my front or back in her carrier on my co-op shifts. (I used to beg the children not to bang their tin plates on the table, because it always made her wake up early.)

But also because playschool is all about babies, or at least no one loves babies more than the kids there do. They love books about babies, and pictures of babies, and playing with dolls that are babies, and little brother and sister babies. They push babies in strollers and plastic shopping cards, and shoved inside their shirts with babies’ heads poking out, a DIY Baby Bjorn kind of deal.

I also knew that with its inclusivity of characters from different races, who live in different countries and come from different cultures all over the year, and its representation of diverse families and physical ability that this was a book that playschool would be able to get behind. Government policy dictates that inclusive toys and images featuring racial diversity and disabled people must be present in all play areas of the classroom. On one hand, that’s “political correctness gone mad” [and kind of tricky for a non-profit to fund] but three seconds later I realize the implications of young children growing up with images omnipresent, diversity being just normal for them. Because it actually is.

Finally, Up is a playschool book, because playschool is all about stories. These kids know books. In all my years of co-opping, I’ve never once sat down to read a picture book and not found myself surrounded by children wanting to hear the story (including the ones fighting to sit on my lap). These kids have an ever-changing range of books to choose from on their story shelf (from a huge and incredible library in the back room that stretches back decades. Some books never go out of style). They get trips to the library, and stories every day, and at free time many of them elect to pick up a book and sit down with it.

And so we’ll leave a note on the inside cover of this story, thanking playschool for so many extraordinary years (and days!) and letting them know that this is a gift from us. It’s nice to think of the children in the years ahead who’ll be enjoying this book while my own are out exploring the wider horizons playschool has set them on a path toward.

May 30, 2017

Big As Life

I fell in love with Sara O’Leary’s picture books back when I wasn’t even into picture books, before I had children. I discovered her via the blog Crooked House, when Stephany Aulenback published an interview with her in 2007. (Stephany Aulenback delivered me to all the best things, and I miss her blog: she is also the reason I read Harriet the Spy.) I loved O’Leary’s first picture book, When You Were Small, and it’s where my love of Julie Morstad’s work began—we’ve now got a print of hers hanging in our hallway. All of which is to say that Sara O’Leary’s work has been a part of my life in an essential way for a long time now.

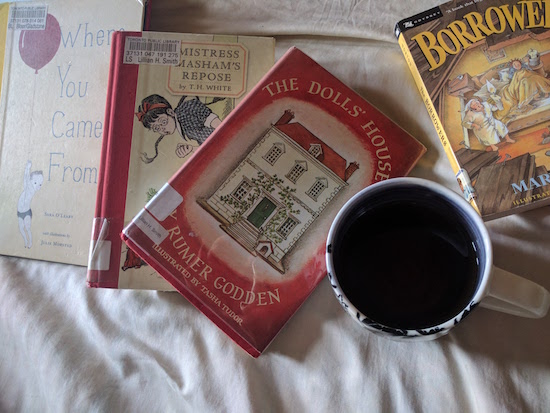

And so I was particularly delighted by the opportunity to write about her books for The Walrus, an adventure that had me revisiting microscopic books at Toronto Public Library’s Osborne Collection and calling them up to clarify just how many miniature books they had—amusingly, all online references noted the collection of miniatures was “sizeable.” I got to revisit The Borrowers, and read Rumer Godden’s The Dolls’ House and T.H. White’s Mistress Mashem’s Repose. I was also recommended Jerry Griswold’s fascinating book, Feeling Like a Kid: Childhood and Children’s Literature—the chapter on “snugness” was my favourite.

So much stuff I came up with didn’t make it into the final piece (1800 words is not so long…) but it was all so fascinating. Everyone was sick in my house on Christmas Eve, which was annoying but left me free to read the entirety of O’Leary’s collection of short stories for adults, Comfort Me With Apples. (Note: she also has a novel for grown up children forthcoming next year, a ghost story which, unsurprisingly, features a dollhouse…) I was particularly struck by O’Leary’s preoccupation in these stories with so many of the ideas that would surface in her work for children a decade or more later—children with indeterminable origins, the fundamental unknowability of mothers, families that weren’t the way they were supposed to be, subtle allusions to nursery rhymes, and particularly ideas about size and scale.

I found O’Leary’s novella in the collection, “Big As Life,” made for the most fascinating companion to her Henry books. It begins with a woman sharing her first childhood memory, which her mother informs her is not a true memory but more likely something she dreamed once. This mother too who wishes to foster a more equal relationship with her daughter, to be like roommates who where the same clothes, which reminds me of the mother in When I Was Small who tells stories so she and her son “can be small together.” Lost photographs, so the woman is unable to corroborate anything she remembers from when she was small. The mother talking about her pregnancy, explaining, “Even though I was getting bigger all the time it felt like I was disappearing.”

This one extraordinary part where the women recalls the stories she used to tell her baby brother about when he was small: “I tried to tell him about who we were, what we’d been doing before he came along…I never prayed when I was a child, but somehow, telling my baby brother all I knew about life so far, I came close.”

And then this one incredible paragraph, from the perspective of a child watching her mother:

“The expression on her face—it was like she was aloft in a hot air balloon and we were all rapidly diminishing to the size and importance of ants on the ground below. It was as though soon we would grow too small to be seen, disappear, never to have existed at all. This, at least, is what I imagine, years later, trying to remember why I had grown suddenly enraged at the sight of my mother reading a book and smoking a cigarette.”

I am not sure at the connections one could make between the two works, what they mean. From reading the picture books we know that ants are actually pretty important after all and there is reverence for smallness—but perhaps you have to grow up in order to fully understand this. I think you also have to be grown-up to appreciate a mother’s desire to sometimes float away.

Parent/child relationships are complicated and fraught, it is true, but as I write in my Walrus piece, O’Leary’s picture books offer the suggestion of connection—just one of the many possibilities of small things.

May 26, 2017

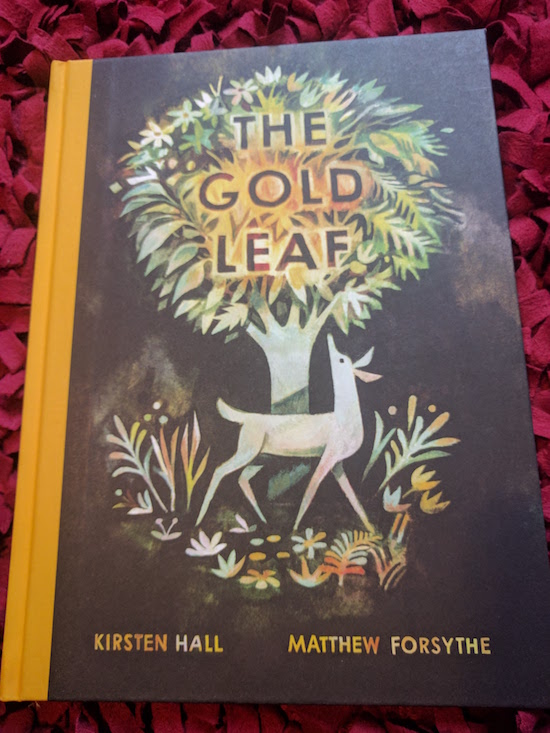

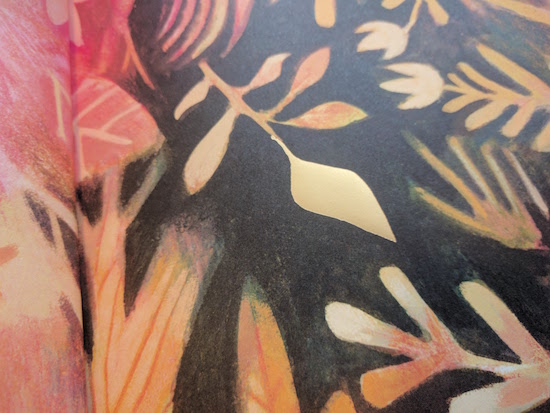

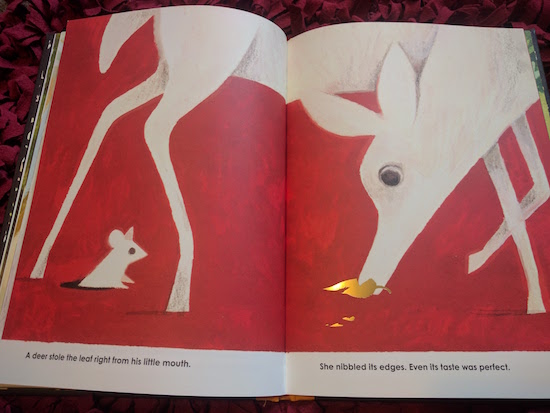

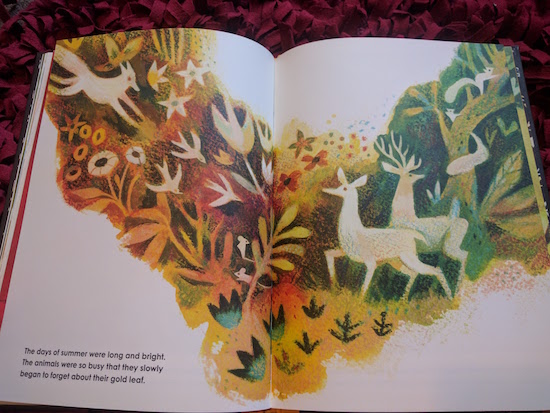

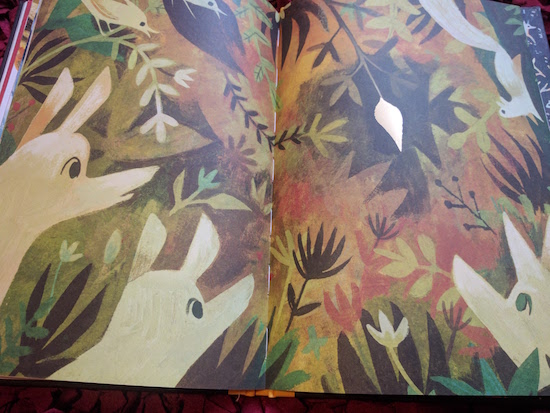

The Gold Leaf, by Kirsten Hall and Matthew Forsythe

The Gold Leaf is the kind of book that you’d think at first glance was by an author/illustrator, a conceptual book in which the images are fundamental. Beautiful, lush, classical styled illustrations of a forest turning into spring.

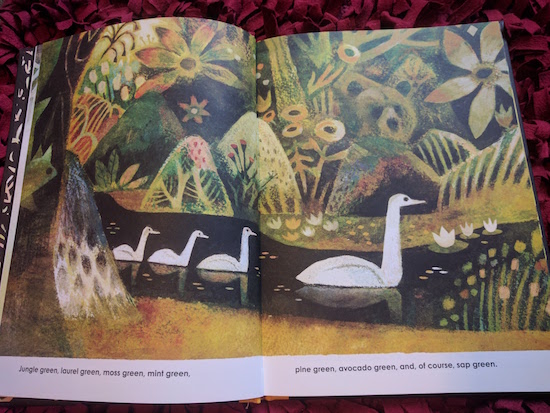

But then the words too, all the ways to describe greenness. “Jungle green, laurel green, moss green, mint green, pine green, avocado green…” I love any book that emphasizes the many different ways there are to be one thing. I also love how in this case, the splendid text is enriching the picture.

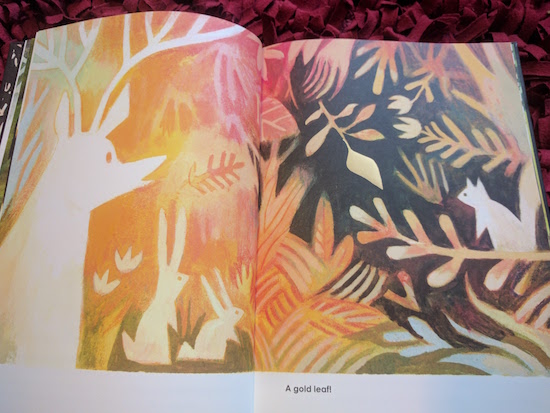

Anyway, the animals are awakening from winter slumbers and in all the newness and excitement, everyone almost misses the sight of something most unusual:

An author’s note explains the process and history of gold leaf as an art form, as well as the the author’s grandfather was responsible for the gold leafing on many famous buildings in New York City, adding another layer of texture to this beautiful story.

Well, obviously the gold leaf is coveted amongst the forest creatures, and one after another they snatch it, keep it, grab it and run, and the inevitable occurs—the leaf falls to pieces, scattered in the wind. And then life in the forest goes on as it should—until the following spring (with “pear green, pickle green, parakeet green…”) when the gift returns to them. A story about second chances, gifts and mercy, maybe, and community, precious resources, and how much richer we are when we take care of each other.

The book, in its exceptional design and quiet story, reminds me of Coralie Bickford-Smith’s The Fox and the Star, which we loved, and also a little bit of Kyo Maclean’s beautiful new book, The Fog, with its subtle environmental message and open-endedness (and also a warbler). And yet its utterly itself as well, and we absolutely love it.

May 19, 2017

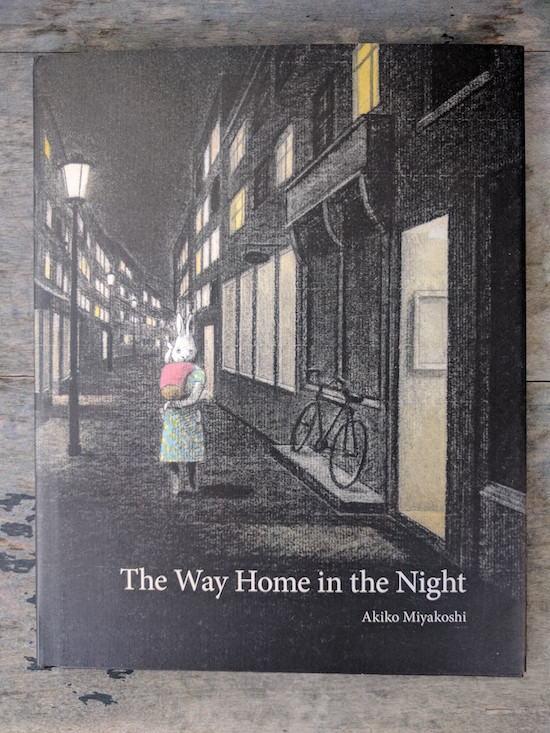

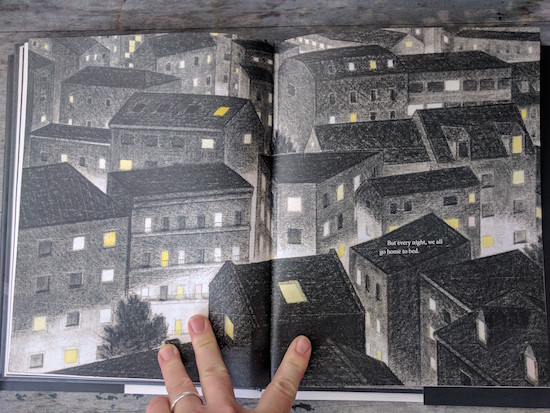

The Way Home in the Night, by Akiko Miyakoshi

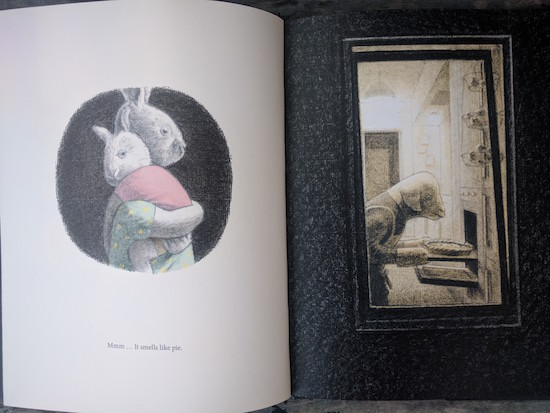

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that everyone has their own story, about light in the dark, and pie, baths and bookshops. (The final clause of that sentence is evergreen, but still.) The Way Home in the Night, by Akiko Miyakoshi, brings all of these ideas together in a quiet thoughtful way and manages to be a lullaby—for the whole wide world.

(Check out the endpapers:)

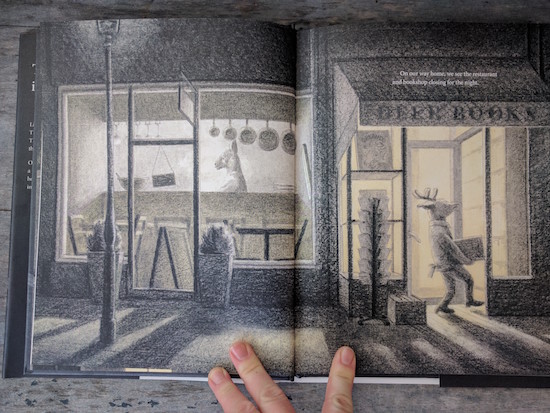

Miyakoshi’s third book in English (after The Tea Party in the Woods and The Storm), The Way Home… is about a child (rabbit?) coming home when its late, sleepy in her mother’s arms. They walk together in the darkness of the city, past stores closing up shop, through empty streets which are illuminated by streetlights and the lights from people’s windows.

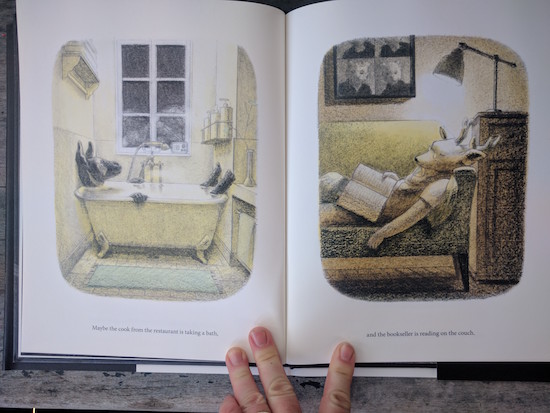

The child hears vague sounds, smells different scents in the air, and ponders what these tell us about what’s going onside the lives of the people at home in all the houses.

And I love that—curiosity about the lives of others, an acknowledgement that everybody is a character in their own story, stories we only sometimes get a glimpse of. That each of us is not the only person in the world, even, and that when we sleep—settling down to the bed as the narrator does after her mother tucks her in—the world is still going on without us, people going places, other people coming home.

The book then turns into an exercise in storytelling as the rabbit drifts into sleep, imagining the characters she encountered on her journey making their own way home, drawing a bath, settling down with a book. What can we know about other people, the book is asking us. And what does it mean when we bother to try? The point being that this wondering is what connects all, each of us with our own lit windows, our self-contained universes. In fact, we’re all a constellation.

May 4, 2017

A Bird Chronicle, by Ruth Ann Pearce & Rina Barone

I’ve been following Curiosity House Books on social media for awhile now, so when I finally got to visit Creemore on Saturday, a highlight was getting to see the picture book created by their in-house publishing company in real life. A Bird Chronicle is an ABC book, a bird book, and an art book. It’s even a font book—every letter and bird has its own typeface, i.e. H is for “Half-collared Kingfisher” and also for “Hoefler“; O is for “Ostrich” and “Optima.” Most of these are birds I’ve never heard of before (“i’iwi,” anybody? Or turquoise-browed motmot?) and each one is given a name (alphabetically, of course, i.e. the American Kestrel is called Andy) and a little alliterative verse that tells us something about the bird’s habits or habitat. It’s all a little bit abstract, but fun to read—try saying, “Oh how she wishes the fishes would just hurry up…” and not feel good. Each bird had a vivid colour illustration, accompanied by a very cool silhouette, and the whole thing is lovely. I would have bought it—even if H and I had not turned out to be particularly close to home… It’s a gorgeous, singular and enjoyable book, and everyone at our house has fallen in love with it.

April 21, 2017

Stop Feedin’ the Boids, by James Sage and Pierre Pratt

There are several levels in our appreciation of Stop Feedin’ Da Boids, the new picture book by James Sage and triple Governor-General’s Award Winner Pierre Pratt.

Number One: the whole wildlife in the city thing. I was a fan of Alissa York’s Fauna a few years back, and this story similarly illuminates the wildness hiding in the concrete jungle—and not just the people and their dogs either. Pratt’s beautiful spreads bring the diverse and frenetic city to life, and this is a city in particular: Brooklyn, to which Swanda has moved after years in the countryside, leaving rolling hills and animals grazing in pastures behind,

Number two: the pigeons. This has been a season for birds, literary-wise, but pigeons still don’t get a lot of respect. The great thing about wandering the city with children, however, is that they don’t discriminate, and pigeons and sparrows are as marvellous as downy headed woodpeckers. In fact, imagine seeing a pigeon for the first time in your life. Wouldn’t you think it beautiful? So I can kind of understand their appeal, why the animal-loving Swanda jumps on the pigeon-feeding train…but things quickly spiral out of control and soon the neighbourhood is overwhelmed in that particular way only pigeons can make an urban place.

Which brings me to the third level of our book appreciation, the splendid moment in the text when, after reading the scrams and the shoos and the subtle suggestions by neighbours and experts (“I’m afraid the problem with pigeons was ever thus…”, when finally, finally, push comes to shove, and the reader gets to proclaim with the entire city street:

It’s intoxicating, that proclamation. And now my three-year-old has taken to calling birds “boids,” and it’s catching. And now we kind of want to move to an apartment in Brooklyn with big old windows, fire escapes and a superintendent called Mr. Kaminski… By this point, however, Swanda has started feedin’ the fish, and you’re going to have to read the book to learn how that turns out.

April 14, 2017

The Fog, by Kyo Maclear and Kenard Pak

Sometimes it is useful to be reminded that not everything is an allegory. But at the same time, those “It doesn’t have to mean anything! It’s a story!” people are even more annoying, because a story has to mean something, or else what is the point? Which isn’t to say that every book should necessarily be Animal Farm. The answer, as with most things, is somewhere in between, and in her latest picture book, The Fog (illustrated by Kenard Pak), Kyo Maclear has achieved that balance with stunning precision.

Maclear’s early picture books had obvious messages—Spork was about being mixed-race, Virginia Wolf was about loving someone with depression, Mr. Flux about learning not to fear change. They were good books and artful, but Maclear’s more recent work has become less concrete, more nuanced. While I’m entirely in love with her book Julia, Child, however, I admit I’ve never been able to get my head properly around it; it’s a book a little too intent on trying to mean. Her others like The Specific Ocean, however, manage to mean without trying to. And her latest, The Fog, is her best work yet.

It’s a book about a bird who likes to people-watch (and this book ties in nicely with Maclear’s recent memoir, Birds Art Life). The endpapers are illustrated with human varieties—”Dapper Bespectacled Booklover,” “Masked Bohemian Weaver,” “Solitary Knitter.” The bird is named Warble and he lives in a place called Icy Land, an island that people from all over the world come to visit, giving Warble excellent opportunities for spotting. One day, however, a thick fog descends, and everything changes. It’s hard to see, the people stop coming, but nobody seems to notice. Nobody, however, except for Warble.

The birds around him adapt—this is what living creatures do. Soon, nobody else remembered that there hadn’t always been fog, and even Warble began to wonder if things had ever been different.

But one morning something happens. Peering through his bins (I say “bins” instead of binoculars because I’ve just finished Steve Burrows’ latest Birder Murder Mystery and I know the lingo…) Warble spots a speck on the horizon: “Peering closely, he saw a dark-haired human ghosting through the meadow. It was a rare female species and she was singing a song.”

The usual transpires: he offers her insects, she teaches him origami, and then they both acknowledge the fog. And they wonder—if each of them can see it, might somebody else out there be able to see it too? So they send out paper boats with the message, “Do you see the fog?” and after a long, long wait some answers return. “Notes arrived from around the world: “We can help!” “We see it too!” And with every message received, the fog lifted a bit, until you could see things again. “Big things. And tiny things. Shiny red things. And soft feathery things.” The story ending with Warble and the girl together against the starry sky enjoying the clear night view.

So what is the fog then? Is it climate change denial? Is it fascism? Is it the volcanic ash that enveloped Iceland in a cloud not too long ago, grounding flights around the world? None of these suggestions mapping onto the book exactly, but in this they serve to open up the story and the ideas it offers rather than rendering them in a narrower fashion. What does it mean? becoming the beginning of a conversation.

April 7, 2017

A Horse Named Steve, by Kelly Collier

Is there room in Canadian literature for another equine creature who’s got a couple of quirks? Which is to say, if you have a thing for roly-poly ponies, do you actually need a horse named Steve?

But you do! Because it turns out that A Horse Named Steve is a genus all onto itself.

The debut picture book by Kelly Collier, A Horse Name Steve (published by KidsCan Press, which just won North American Publisher of the Year at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair) is a fun, comics-inspired tale of an ordinary horse who wants to be exceptional. When he finds a gold horn lying around (as you do) he imagines an exceptional life lies before him now, but then when he gallops off to show the golden horn to his friends, things go ever so slightly…askew.

With the horn out of place, Steve’s colleague, Bob the Racoon, reports to him, “I don’t see a beautiful gold horn on your head. You are not exceptional.” Which comes as a shock, and poor Steve cries so hard he gets thirsty, and when he goes to get a drink, our little pseudo-Narcissist sees in his reflection that the gold horn is right there after all. It’s no use though, because horses are not so dextrous in this respect, and when he goes to fix his horn, Steve ends up falling in the water. “Poor Steve. He is hornless and drenched.”

The tragedy that has befallen him has a positive outcome though—turns out that Steve’s horn has started a thing-on-the-head mania amongst the forest creatures, and when he falls in the water and his horn gets lost…suddenly Steve is exceptional again. Turns out bare heads are where it’s at after all—”I love the natural look he’s got going,” says the rabbit, the other animals agreeing, “Very stylish. How does he do it?”

Surely there are lessons contained within about the importance of accepting one’s self, being an individual, blazing a path instead of following a path, etc. But the great charm of this book is that these ideas exist deep in the background while A Horse Named Steve manages to be exceptional in its own right—the simple drawings, the humour, the chatty asides that make reading the book aloud an absolute delight.