November 10, 2017

Whispers of Mermaids and Wonderful Things

Full disclosure necessitates I tell you that I had lunch with Sheree Fitch yesterday, although possibly I’m just telling you that because I’m still marvelling at the fact that I had lunch with Sheree Fitch yesterday. Sheree Fitch, whom we travelled to Nova Scotia to see this summer on the day her seasonal bookshop opened. Sheree Fitch is the most extraordinarily generous brilliant person I’ve ever known, a woman whose books have been the framework of my life as a mother and remember when a tiny Harriet crashed the stage to read with her at Eden Mills years and years ago? Although I was one of hundreds upon hundreds of people who traveled to River John, Nova Scotia, to see Sheree Fitch this some, because she is the sort of person who inspires such a gesture.

Even fuller disclosure: Everything Sheree Fitch touches is more than a little bit magic.

Although in the case of her latest project, the anthology Whispers of Mermaids and Wonderful Things: Atlantic Canadian Poetry and Verse for Children, co-edited with Anne Hunt, she’s not the only magic-maker. Credit belongs too to the designer of this gorgeous book whose cover art is absolutely enchanting, along with delightful leafy end pages, borders, and yellow ribbon to hold one’s place. And to her co-editor too, with whom Fitch has selected these works, and to the poets too, some of whom—Fitch herself, Jennifer McGrath, Kate Inglis, Al Pittman—I’m familiar with through their words for children, and others—Lynn Davies, Kathleen Winter, Sir Charles G.D. Roberts, E.J. Pratt, Alden Nowlan—I know if a very different context.

So how do you use a book like this, a pretty book with a ribbon, a book that isn’t a picture book because there aren’t any pictures? Which is to say, how does one awaken the magic within, the whispers of mermaids and wonderful things? And the answer, of course, is to read it. To take book off the shelf and leaf through at random, see where the pages fall open or where the poem catches your eye. To make a ritual of it, a poem before bed, perhaps, or first thing in the morning, like a vitamin. To revel in the words and rhymes, and share that wonder with the people around you. Let beginning readers have a chance to read these poems too, to experience the pleasure saying their phrases, how the words feel in their mouths.

This is a book that will make an extraordinary holiday present for (or from!) anyone with an affinity for words or poems, or an affiliation with Atlantic Canada. It’s such a beautiful object, a treasure, and then you open it up, and there are worlds upon worlds inside to explore.

November 3, 2017

Captain Monty Takes the Plunge, by Jennifer Mook-Sang and Liz Starin

Is it wrong to fancy a mermaid? Well, it mustn’t be so wrong, because sailors have been doing so for centuries. But is it wrong to fancy a mermaid in a picture book? One who’s already in a relationship with a pirate who is also a cat? Well, if loving a picture book mermaid is wrong, I don’t want to be right.

And it’s not like Meg is just any picture book mermaid. “She’s like you, Mommy,” said my daughter. “She has a star tattoo.” And I remind my daughter, “We also both have awesome squishy tummies.” Because Meg the mermaid is the kind of mythical creature you want to have a lot in common with. She’s cool. She plays the ocarina, likes bad jokes, and she teaches Captain Monty how to set his course by the constellations, which is a useful thing for a pirate captain to know.

While she might be a punk rock mermaid, Meg still swims like a fish, displaying amazing skills that put poor Monty (who’s afraid of water) to shame. And she’s got standards too: when Monty asks her out, Meg turns him down. Because a guy who’s afraid of water never gets a chance to bathe, and she tells him, “You’re a real nice pirate, Monty, but you smell like stinky boots.”

When Meg gets captured by an octopus, however, Monty has to step up to save her. Which he kind of fails at, until he thinks up a clever way to outwit the many-legged sea creature, and Meg joins in on the action, the two of them rescuing themselves together. And all that is pretty romantic, so of course they fall in love. “My brave Monty,” Meg tells him. “Now that you smell like fresh air and seaweed, would you like to have dinner with me?”

Captain Monty Takes the Plunge, by Jennifer Mook-Sang and Liz Starin, is a fun and lively book for any young reader who’s into pirates, dislikes bathing, and/or requires just a few more ounces of courage before she leaps into the pool. But it’s Meg who steals the show, a fabulously subversive and feminist rad mermaid, and she’s the reason we keep returning to the book again and again.

October 27, 2017

You Hold Me Up, by Monique Gray Smith and Danielle Daniel

My children delighted in You Hold Me Up, by Monique Gray Smith and Danielle Daniel. As we read it, my littlest kept guessing what the text might be based on the image. “When you dance with me!” she offered, for the “you hold me up when you play with me” page, so she wasn’t wrong. She also guessed, “When you yawn with me,” for “when you sing with me,” which is a little bit wrong, but then we all started yawning, underlining the point of the book, that we’re all connected to each other.

Monique Gray Smith is the award-winning author of Tilly: A Story of Hope and Resilience, and children’s books My Heart Fills With Happiness (which I read last year) and Speaking Our Truth. I also really recommend her podcast, Love is Medicine. Illustrator Danielle Daniel won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award for her first book, Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, which we loved, has another new picture book just out, Once in a Blue Moon, and I also really liked her memoir for the adult set, The Dependent—my review is here. The idea of these two teaming up on a project has had me looking forward to You Hold Me Up for ages.

Smith’s text is simple, but powerful, about the small and essential ways we all support each other. “You hold me up when you are kind to me…” it begins, accompanied by a photo of an Indigenous family in the kitchen baking together. “…when you share with me…when you learn with me.” Daniel’s illustrations have a playful approach, but are also nicely stylized and textured, with a collage effect and fine details, warm and familiar images of people together.

“It’s about family,” Iris proclaimed when we got to the end of the story, the line, “We hold each other up,” with the facing image of two adults, their children, and a grandmother having a picnic under birch trees. And she’s not wrong here either, except it’s not only that. Smith writes in her Author’s Note of Canada’s “long history of legislation and policies that have affected the wellness of Indigenous children, families and communities.” Like her My Heart Fills With Happiness (and in everything she does, really) Smith is writing about survival and resilience, about the strength and power that comes from the love we give each other.

October 20, 2017

Rapunzel, by Bethan Woollvin

I love me some side eye, the sweet subtle rebellion of a woman who’s got no time for your nonsense. A woman who’s tired of outdated tropes, stereotypes, and sexist cliches. The thing about fairy tales, of course, is that they’re fluid, ever-changing. Even the tired versions of the stories aren’t ever told the same way twice, so one could feel justified in making some adjustments. “[W]hoever makes up the story makes up the world,” Ali Smith writes in her novel, Autumn, and I love that idea. In her first book, Little Red, Bethan Woollvin is making up a world where little girls don’t fall for wolves in bad disguises and get along just fine without the help of a Huntsman, thank you very much. She continues to make such a world in which girls can be their own heroes in Rapunzel, whose heroine rescues herself from the tower and becomes a masked vigilante on horseback—which was clearly a detail that was missing from the original tale. And the very best thing, when you put Little Red and Rapunzel together? The side-eye is solidarity, of course. These two fearless girls are looking right at each other.

October 6, 2017

When We Were Alone, by David A. Robertson and Julie Flett

Please forgive the absence of a proper Picture Book Friday post but my phone broke so I can’t take photos, plus my children are off school tomorrow schedules are all askew. But I did make time to run out to Parentbooks this afternoon to pick up a copy of When We Were Alone, by David A. Robertson and illustrated by Julie Flett, whose work I so adore. Partly because Orange Shirt Day was observed at my children’s school last week, and I wanted this book to contextualize it. And also because When We Were Alone has just been nominated for a Governor General’s Award, on the trail of big wins at the Manitoba Book Awards earlier this year and a nomination for the TD Children’s Literature, whose winner will be announced next month. I’d read it earlier this year while we were at the Halifax Central Library, but I didn’t read it to my kids because the book made me a bit nervous. I’d interpreted the title in a sinister fashion, and knew the book was about residential school survivors, and really, I wasn’t sure even I wanted to know what had happened when these poor kids were alone.

But I was wrong, for so many reasons, not least of all in thinking that these kinds of stories were the sort I could ever turn away from when so many other people don’t have that luxury, but also because it was when the children were alone that they were free and used all kinds of smart and beautiful ways to subvert the tyranny and abuse of residential schools. For example, where they had their hair cut short, and dressed in drab uniforms, and were forbidden to speak their languages. But when they were alone, the narrative goes, the children would braid long strands of grass into their regulation short hair, and decorate their bodies with colourful leaves, and hide in the fields far away from everybody else and talk to each other in Cree. So that this is a story of resilience and survival, even more so because the story is told through the perspective of a young girl who is asking her Kokum why she does things the way she does—have her hair so long, wear bright colours, speak in Cree, and Kokum explains that she does all these things because once upon a time she couldn’t.

September 29, 2017

The Man Who Loved Libraries, by Andrew Larsen and Katty Maurey

Harriet has decided she’s going to be Jane Goodall for Halloween, mostly as an excuse to carry around a stuffed monkey at school, but it seemed like a good excuse for a little educating. So I put a bunch of kids’ biographies on hold at the librarian, and they all came in on Tuesday. Tuesday was the second day of a heat warning here in Toronto, a stop at the library on the walk home from school serving as a very good pit-stop. And when we got there, the place was packed, people escaping the heat, reading books and magazines, kids spinning on the spinning chairs, playing games on the computer, washing their hands in the bathroom because they were sticky from where popsicles had melted in the heat.

The library is for everyone, I was thinking as I took in the scene on Tuesday, Harriet gathering her stack of books, heading over to sign them out on the library we got for her when she was just a few weeks old. I’ve written before about how important the library was to me when Harriet was small, and our experiences with phenomenal children’s librarians underlined my children’s pre-pre-school years when I was home with them, and taught me the stories and songs that would become the foundation of our familial literacy. Our kids continue to attend library programs. We visit as a family every couple of weeks, and borrow so many books we need to bring a stroller in order to cart them home. Books and reading are a bridge between the thirty years that divides me from my children; reading books together is the one activity that we’re able to reap enjoyment from on the very same level. And the library has ensured there’s always something new for us to explore.

But the library isn’t just for us, the already book-spoiled. The library ensures that everyone has access to knowledge, to learning, to entertainment. To bathrooms too, and a place to sit down, and cool enough (or warm up, as the case may be). For a lot of kids, it’s where they get their access to computers, to the internet. It’s where people learn to format their resumes, where lonely people find company, where postpartum mothers go to give their muddy days a shape. For some people, the library is a comfortable place to sleep. They’re community centres, schools, literacy hubs. They’re about trust, community, democracy. I read a post recently where someone posited that if libraries didn’t exist and someone tried to invent one, you’d swear it would never ever work.

The funny thing that I hadn’t considered when I started this post is that I met Andrew Larsen at the library. We live in the same neighbourhood, and met when Harriet was small and he was on the cusp of publishing his second book, I think. And I would learn that he too felt the library had been essential to his experience as a stay-at-home parent, eventually leading his emergence as a children’s author. We have loved the books he’s published since, books that have delighted our family (“I read Andrew Larsen’s squiggly story today, Mommy,” reported Iris this very afternoon when I picked her up from junior kindergarten.) I’ve savoured our conversations on our walks to school together, and miss him now that his children have moved on to bigger kid things.

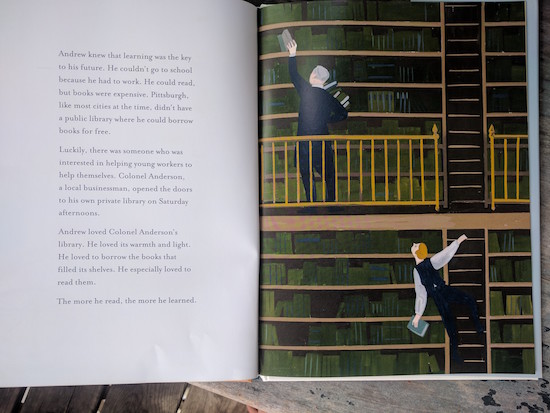

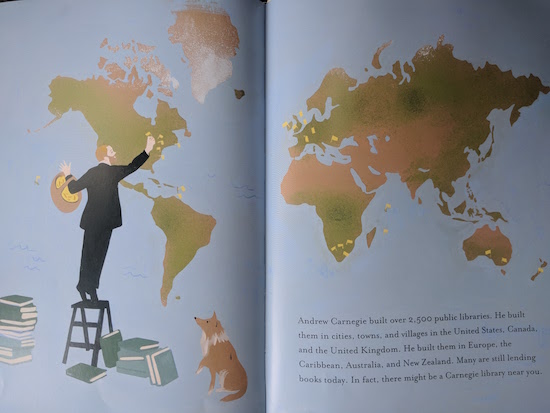

Andrew Larsen’s latest is a picture book biography of Andrew Carnegie, The Man Who Loved Libraries, illustrated by Katty Maurey who was also behind Kyo Maclear’s The Specific Ocean, another picture book we’ve loved. I’m familiar with Carnegie in theory, because he’d helped to build libraries in both of the Ontario towns I grew up in, as well as the Beaches, High Park and Wychwood Libraries in Toronto, among many many others. But Larsen’s story fills in the gaps—Carnegie was born in Scotland and moved to America as a child with his family who were looking for a better life. His first job was in a cotton mill, where he was a bobbin boy. A hard worker, he strove to get better work, and find whatever education was available to him. He made a point of teaching himself skills that would be relevant for work, but also was able to acquire deeper knowledge by accessing the private library of a wealthy businessman who opened its doors to workers on Saturday afternoons.

When Carnegie was 17, he got a job as a telegraph operator with the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, and by age 25 he was working in management. He started to make money, and invest money so that he made even more money. “By the time he was thirty-five, Andrew Carnegie’s investments had made him a rich man. He had more money than he could ever need. So what did he do?” Remembering the literary riches that had been shared with him in his youth, Carnegie worked to open public libraries so other working people could access books and learning. Carnegie’s first library was built in the Scottish village where he was born, and he would eventually build 2500 around the world.

Carnegie’s legacy is a mixed one, as a note at the back of the book makes clear. He fought against unions and resisted his employees’ efforts to fight for better working conditions and wages. As with everything, it’s complicated. But still, The Man Who Loved Libraries will provoke interesting conversations and make young readers reconsider ideas they might previously have taken for granted. At this moment in Western democracy, we need to underline the value of public libraries more than ever.

September 22, 2017

Mr. Crum’s Potato Predicament, by Anne Renaud and Felicita Sala

I was going to say that chips are my weakness, but I prefer Stephanie Domet’s term, that they’re her “kryptonite.” Domet is the inventor of the #stormchips hashtag, a Martime phenomenon in which an impending storm necessitates the procurement of snack food, chips mainly. Last winter in our household I tried to make #stormchips into a thing, keeping a bag on hand in case of blizzard, except we don’t have the right kind of climate and I just ended up eating chips without a storm. Who needs a storm? Not me, which is why I can’t buy chips, but I love them. One after another, crispy, salty, greasy, kettle-baked, and preferably flavoured with salt and vinegar.

I had a bag of chips last weekend, Old Dutch Chips, because I was in Edmonton and they’re a western thing. I ate them on my flight home and they were so good my eyes actually rolled back into my head, and the thing about something this amazing is the remarkable fact that you can just have them. That there are chips in the world at all, I mean, readily available at any moment to be eaten, usually in giant handfuls. I am incapable of eating potato chips without stuffing them into my mouth like a madwoman, a chip-monster. I have never been able to eat just one chip or a couple. This is my problem. I’m not terribly bothered by it.

For all my talk of can’t buy chips and won’t buy chips, I buy a lot of chips, or at least lately. We eat chips when we’re camping or when we’re at the cottage, and there was a moment this summer when I was actually a bit tired of chips. Which it had never remotely occurred to me was possible. But last weekend’s chips were special occasion, chips outside of season. Although that I was on an airplane at the time kind of negates the whole occasion; I was in transit and one could argue it never really happened at all. The Old Dutch thing was really on my mind because I’ve got the new book Snacks: A Canadian Food History on deck, which I’m planning to read in the company of a bag of Hawkins Cheezies, and probably some chips. And I don’t think it’s weird to plan your reading material around their snacking opportunities. Because if there’s one thing I know, it’s that you can’t eat chips without occasion.

Fortunately, there is one more literary occasion for opening up a bag of chips, and that’s the picture book Mr. Crum’s Potato Predicament, by Anne Renaud and Felicita Sala, and it will make you hungry. (It also reminded me of Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad’s Julia, Child in all the best possible ways.)

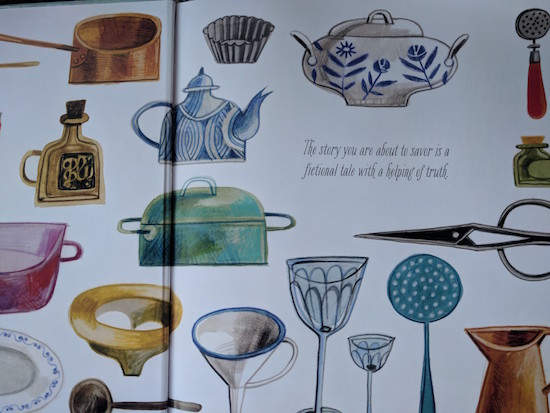

“The story you are about to savour is a fictional tale with a helping of truth,” the book begins, and then the reader is introduced to George Crum, his waitress Gladys, and the persnickety customer in George’s restaurant whose pickiness would lead to the advent of potato chips, as George is encouraged to cut his fried potatoes into thinner and thinner slices in order to satisfy his customer’s particular demands. The story is playful and light hearted, with a fantastic vocabulary, rich with synonyms and adjectives and gorgeous euphony. Crum was a real figure, Renaud’s author’s note informs us, though he is but one of many people credited with invented chips with his thin potatoes. But Crum certainly did play a role in making chips famous, and both author and illustrator have a lot of delicious fun bringing this historical character to life.

September 8, 2017

Buddy and Earl Go to School, by Maureen Fergus and Carey Sookoocheff

I love September—cardigans, golden light and sharpened pencils—but I also hate September. I always did. Because I hate change, although I’ve been trying hard not to let my children catch onto this. And while I loved the possibility of fresh starts, clean slates and pristine pencil cases, there was always an adjustment. New classes, new friends, old friends who had become new people, new teachers—I would find these things very difficult. I still do. My children seem to be doing perfectly fine, but I have had a difficult week adjusting to grade three and junior kindergarten—who would have thought it? All the tumult and violence going on in the world hasn’t helped the matter either.

And so I’ve sought solace in good things, sweet things and funny things. Buddy and Earl Go To School, by Maureen Fergus and Carey Sookoocheff is the fourth book in this series about a dog and a hedgehog and (although I think I’ve said this about previous titles, but still) it’s the best one yet! I can’t say what it is we like so much about these books at our house exactly, except that it involves the fact of a hedgehog, plus Buddy the dog’s deadpan address and aversion to contractions. It is understated, adorable comic genius.

In this story, Buddy and Earl are starting school. “‘Hurrah!’ cheered Earl. ‘Getting an education is the first step to achieving my dream of becoming a dentist.’ / ‘I do not think think hedgehogs can become dentists, Earl,’ said Buddy./ ‘With the right education, I can become anything,’ declared Earl. ‘And so can you, Buddy.”/ Buddy was very excited to hear this.”

When they turned up at school, the setting defied my expectations but was also so perfectly familiar. The school day proceeds in adorable funny fashion, and even when Earl was bored (“How long until gym? Is it almost snack time?”), we weren’t. And by the end of the book, I’m left with a bit more pep in my step. Every school day can be rich with surprises, and there is promise i September after all.

August 31, 2017

Me and You and the Red Canoe, by Jean E. Pendziwol and Phil

“We’re going to have to shut the windows,” I called out a few minutes ago. I’d gone outside to take photos for this blog post, and they’re possibly a bit blurry because I was shivering. There are only a few hours left of August, and tonight the temperature is supposed to go down to 7 degrees. Summer has ebbed, though there is still a long weekend left, and tomorrow we’re taking the ferry to the Toronto Islands and intend to play on the beach, even if it’s a little bit freezing and it might all be a bit English seaside. But we like the English seaside, and it seems a fitting way to spend the last day of summer holidays—beside the water, feet in the sand. We’ve had that kind of summer.

We are not big canoeists. Once in the Lake District, my husband and I rented a rowboat, and I ended up screaming at him as he steered us into a dock full of tourists, and it wasn’t very romantic. So we’ve been a bit wary of nautical vessels ever since then, unless they’re inflatable flamingos, which we’re all over. Literally. But still, Me and You and the Red Canoe, by Jean E. Pendziwol and illustrated by Phil, has been a book that (lucky us!) so suits our summer. We’ve had loons and campfires, and empty beaches, and quiet mornings, and twinkling stars and soaring eagles in the sky. Would be that our children could paddle away from us early morning, and return with fish that somebody in our family would know how to prepare. Imagine if anyone knew how to use a paddle…but still. We went kayaking when we were away in July, and it was pretty lovely. Nobody yelled at anyone.

The illustrations in this book are beautiful, seemingly painted on wood, with lots of texture, a lovely roughness, and glimpses of under layers. They’re timeless, nostalgic in an interesting way, and a lovely complement to Pendziwol’s lyrical story, which is so rich in sensory detail and focused in the perfect notes. There’s not a lot of specificity—who are the siblings telling the story? When does it take place? Was this long ago or yesterday? When the siblings woke early and went out early to catch the fish that would be remembered as the best breakfast ever. Observing lots of wildlife, flora and fauna, and quiet and beauty on the way—it’s all the best things about summer, for those of us who are lucky enough to be able to get away from it all. Even if we don’t know how to canoe.

(PS We did visit the Canadian Canoe Museum last week, however! That’s the next best thing to actually paddling a canoe, right?)

June 27, 2017

Four Great Activity Books For Summer

Today is my last day with both children in school, and while I have a million things to do in the scant amount of time I have left, I wanted to carve out a moment to recommend a few activity books we’ve loved this spring, and will be taking with us on vacation this summer to ease the waits in restaurants or to enliven rainy days.

Read All About It is a future journalist’s dream, a fun kit that lets kids put together their own newspaper headlines and stories using stickers, the more bizarre the stories the better.

Professor Intergalactic Cat’s Activity Book is based on the gorgeously illustrated science books by Ben Newman and is packed with games and experiments for kids who are curious about the world around them (and even the worlds beyond!).

And speaking of worlds beyond, we love Astronaut Academy, a fun book for the poor children who can’t make it to Space Camp this summer, containing fun and challenging activities to prepare future astronauts for an experience in space.

And finally Playing With Food, by Louise Lockhart, which is my favourite colouring book ever (the FUN of colouring a vintage kitchen, or choosing colours for a page full of mystery beverages) and a treasure for children of any age who are partial to yummy things and great design.