March 16, 2015

Best Book of the Library Haul: March Break Edition

Our March Break plans are modest ones: museum, art gallery, library, visits with friends in the morning, and then Iris nap times in the afternoons while Harriet watches movies and I work. Unlike the previous years, Stuart doesn’t have the week off too, and I’m less interested in adventuring without him. Though tomorrow I am taking Iris on the streetcar untethered, with only Harriet for support, moral or otherwise, which might be more adventure than I’m bargaining for. Other good things about March Break are that spring temperatures are here and it’s glorious, and also that it’s the first March Break ever during which I’m not awaiting biopsy results—that was always really poor scheduling on my part.

Our March Break plans are modest ones: museum, art gallery, library, visits with friends in the morning, and then Iris nap times in the afternoons while Harriet watches movies and I work. Unlike the previous years, Stuart doesn’t have the week off too, and I’m less interested in adventuring without him. Though tomorrow I am taking Iris on the streetcar untethered, with only Harriet for support, moral or otherwise, which might be more adventure than I’m bargaining for. Other good things about March Break are that spring temperatures are here and it’s glorious, and also that it’s the first March Break ever during which I’m not awaiting biopsy results—that was always really poor scheduling on my part.

Another good thing is that we got a fantastic library haul last week, which has meant it’s March Break, and the reading is splendid. And the best of the bunch is The Worst Princess by Anna Kemp and Sara Ogilvie. I’ve been championing anti-princess princess books for awhile now, but this one really takes the tiara. It’s in rhyming couplets, first, which is my definition of a picture book to die for. And tea and teacups and teapots recur throughout the narrative, which happens in most of my favourite books, and the children delight in pointing them out.

Another good thing is that we got a fantastic library haul last week, which has meant it’s March Break, and the reading is splendid. And the best of the bunch is The Worst Princess by Anna Kemp and Sara Ogilvie. I’ve been championing anti-princess princess books for awhile now, but this one really takes the tiara. It’s in rhyming couplets, first, which is my definition of a picture book to die for. And tea and teacups and teapots recur throughout the narrative, which happens in most of my favourite books, and the children delight in pointing them out.

The Worst Princess is Sue, whose been waiting around for her life to begin, reading up on all the stories to find out just how one goes about landing a princess. She’s grown her hair to extraordinary lengths, kissed frogs, slept on peas, all for naught. She is lonely and terrifically bored, and then delighted when her prince finally comes. Except that he’s built her a tower and expects her to stay in it locked away from the world—it seems that the prince has read all the books too. But Princess Sue has no truck with that. When not long after, she spies a dragon in the distance, she flags him and down and makes a deal (over a cup of tea, of course). He blows down her tower, sets the prince’s pants on fire, and then Sue and Dragon take off on a series of adventures, “making mischief left and right/ for royal twits and naughty knights.”

The Worst Princess is Sue, whose been waiting around for her life to begin, reading up on all the stories to find out just how one goes about landing a princess. She’s grown her hair to extraordinary lengths, kissed frogs, slept on peas, all for naught. She is lonely and terrifically bored, and then delighted when her prince finally comes. Except that he’s built her a tower and expects her to stay in it locked away from the world—it seems that the prince has read all the books too. But Princess Sue has no truck with that. When not long after, she spies a dragon in the distance, she flags him and down and makes a deal (over a cup of tea, of course). He blows down her tower, sets the prince’s pants on fire, and then Sue and Dragon take off on a series of adventures, “making mischief left and right/ for royal twits and naughty knights.”

March 12, 2015

Sidewalk Flowers by Jon Arno Lawson and Sydney Smith

It’s from picture books that I’ve learned that the best books have to be read at least 10 times before you really get a handle on them. Case in point: Sidewalk Flowers by JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith. A wordless picture book (though a wordless book with an author, take note!) can slip past one pretty quickly. The first time I read it, I thought it was okay. A bit weird. The next few times, I still wasn’t sure. It’s the story of a young girl walking through the city with her father, her red-hoodie one of the few spots of colour on the page for much of the book. The other colour comes from the flowers she encounters on her journey, flowers which are actually weeds, which is the kind of distinction only adults make. In their ubiquity, we forget to note how remarkable it is that a dandelion—a living thing—can grow between cracks in the sidewalk. That a wild thing can be so determined to live, and how wildness continually thwarts a city’s attempt to tame.

It’s from picture books that I’ve learned that the best books have to be read at least 10 times before you really get a handle on them. Case in point: Sidewalk Flowers by JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith. A wordless picture book (though a wordless book with an author, take note!) can slip past one pretty quickly. The first time I read it, I thought it was okay. A bit weird. The next few times, I still wasn’t sure. It’s the story of a young girl walking through the city with her father, her red-hoodie one of the few spots of colour on the page for much of the book. The other colour comes from the flowers she encounters on her journey, flowers which are actually weeds, which is the kind of distinction only adults make. In their ubiquity, we forget to note how remarkable it is that a dandelion—a living thing—can grow between cracks in the sidewalk. That a wild thing can be so determined to live, and how wildness continually thwarts a city’s attempt to tame.

And the flowers grow, and the child finds them, picks them. She’s the only one who notices these bits of wild colour on the urban scene, but they’re not all she’s noticing. (This novel’s grasp of the child’s eye view makes it an interesting companion to the award-winning The Man With the Violin). As her father talks away on his cell-phone, and the people around her conduct their business, she sees other things, other colours—the orange of citrus fruit for sale at a greengrocers, the warm yellow of a taxi-cab, a woman in a floral dress who is reading a book at a bus stop. She’s gathering her wild bouquet, part of which she, calling no attention to herself in the process, offers to a dead bird she walks by on the sidewalk, then to a man who is a asleep on a park bench, and to a neighbour’s dog. And as she leaves her flowers, something remarkable is happening to the world all around her—bit by bit, the city becomes rich with colour. Leaves appear on the trees and the sky turns blue. Through the girl’s small acts, the world is transformed.

And the flowers grow, and the child finds them, picks them. She’s the only one who notices these bits of wild colour on the urban scene, but they’re not all she’s noticing. (This novel’s grasp of the child’s eye view makes it an interesting companion to the award-winning The Man With the Violin). As her father talks away on his cell-phone, and the people around her conduct their business, she sees other things, other colours—the orange of citrus fruit for sale at a greengrocers, the warm yellow of a taxi-cab, a woman in a floral dress who is reading a book at a bus stop. She’s gathering her wild bouquet, part of which she, calling no attention to herself in the process, offers to a dead bird she walks by on the sidewalk, then to a man who is a asleep on a park bench, and to a neighbour’s dog. And as she leaves her flowers, something remarkable is happening to the world all around her—bit by bit, the city becomes rich with colour. Leaves appear on the trees and the sky turns blue. Through the girl’s small acts, the world is transformed.

It all happens so subtly, it takes until around the 10th read that it begins to be clear. And even then, the reader is still uncovering new details in Smith’s illustrations—the lion in Chinatown, a cat in the window, the streetcar coming around the corner (which is red!). The images are made interesting and complicated by shadows and reflections, adding extra texture to the story. Smith is depicting an any-city, though the savvy among us will see Toronto with its distinctive architecture and peculiar topography suggested by houses situated up flights up steps on steep hills.

Sidewalk Flowers is a book with mystery at its core, a book that is a manifestation of its theme of generosity, for it has given me something new every time I have encountered it. A wordless book too is an important tool for literacy, for it allows parent and child to remember the reason we open books at all. For them to approach a story for once on the very same level—a whole world to be explored together.

March 10, 2015

An Artist Lives Here

As you know, I love Carson Ellis’s new picture book, Home, and one of its chief delights is the final image, “An artist lives here.” It’s a glimpse into the book’s creation, and a fascinating self-portrait.

It reminded me of another book that we’ve been enjoying, Any Questions by Marie-Louise Gay.

But where is the artist who lives here? Here she is!

And surely, I thought, there must be other examples? It all seemed quite familiar, vivid in my mind’s eye. But when I thought about it, I came up with nothing. Except for Virginia Lee Burton’s Life Story, which isn’t of an artist in her studio (because her studio, as the book tells us, is in the barn behind the house). But there she is down in the lefthand corner painting a picture of the entire scene, finding inspiration in her own surroundings just like Carson Ellis and Marie-Louise Gay.

There must be more though. What other picture books can you think of in which the artist includes an image of the artist herself at home (which is to say, at work)?

February 27, 2015

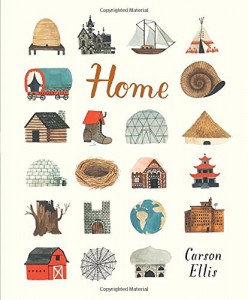

Home by Carson Ellis

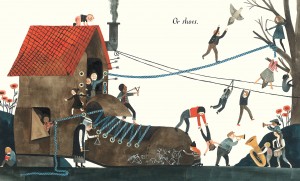

While Carson Ellis’ Home is a beautiful book, it first appealed to me conceptually for its similarity to one of my favourite picture books, A House is a House for Me by Mary-Ann Hoberman and Betty Fraser, published in 1978. Both books—with whimsy, strange and gorgeous illustrations (plus a Duchess)—explore the variousness of dwellings, and the curiousness too; from the Hoberman book, “A box is a house for a teabag. A teapot’s a house for some tea. If you pour me a cup and I drink it all up, Then the teahouse will turn into me.” All this to the point where I opened by Ellis’ book, and wondered where were the rhyming couplets.

While Carson Ellis’ Home is a beautiful book, it first appealed to me conceptually for its similarity to one of my favourite picture books, A House is a House for Me by Mary-Ann Hoberman and Betty Fraser, published in 1978. Both books—with whimsy, strange and gorgeous illustrations (plus a Duchess)—explore the variousness of dwellings, and the curiousness too; from the Hoberman book, “A box is a house for a teabag. A teapot’s a house for some tea. If you pour me a cup and I drink it all up, Then the teahouse will turn into me.” All this to the point where I opened by Ellis’ book, and wondered where were the rhyming couplets.

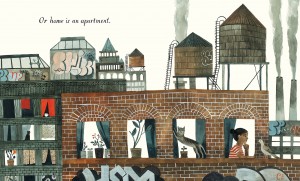

But Ellis’ project with Home is something that’s different, more art-focused than text-focused, and the text itself seeking to open up the book rather than nailing it down, asking questions like, “But whose home is this?” of a home on the edge of a cliff, “And what about this?” of a tiny home underneath a mushroom—a vaguely Alice-ish reference (which gives this book another point in common with Hoberman’s, in addition to a thing for teacups).

So I sat down with my children and we started to look at the book, delighting in the illustrations (which will appeal to anyone who likes Jon Klassen’s work, which is everyone), and the oddities. Sure, homes are boats and wigwams, but what IS going on in that underground lair, and how strange to have “French homes” on a page with the inhabitants of Atlantis (whose homes are, naturally, underwater).

So I sat down with my children and we started to look at the book, delighting in the illustrations (which will appeal to anyone who likes Jon Klassen’s work, which is everyone), and the oddities. Sure, homes are boats and wigwams, but what IS going on in that underground lair, and how strange to have “French homes” on a page with the inhabitants of Atlantis (whose homes are, naturally, underwater).

Homes on the moon, in a geodesic dome in space, the home of a Norse god, a castle in a fish bowl (with the knights riding sea-horses), “A babushka lives here,” “A raccoon lives here.” The strange juxtaposition of the bizarre and familiar—it’s a weird and wonderful book that invites even more questions than those the text poses.

But then we started noticing other things—there is a pigeon on every page, and the same teacup recurs every little while, and there’s a monkey on the ship, and on the shoe-home page, there is a little boy on the roof who’s pulled down his pants, and he’s showing us him bum, and the children were howling. We still couldn’t find the pigeon on the “Bee homes” (though it dawns on me that it’s a wasp’s nest, but I digress) page, so we called in back-up and read the whole book for perhaps the fifth time, in the presence of Daddy. The book was so wholly engaging for the entire family, and we all of us loved it at once.

But then we started noticing other things—there is a pigeon on every page, and the same teacup recurs every little while, and there’s a monkey on the ship, and on the shoe-home page, there is a little boy on the roof who’s pulled down his pants, and he’s showing us him bum, and the children were howling. We still couldn’t find the pigeon on the “Bee homes” (though it dawns on me that it’s a wasp’s nest, but I digress) page, so we called in back-up and read the whole book for perhaps the fifth time, in the presence of Daddy. The book was so wholly engaging for the entire family, and we all of us loved it at once.

“An artist lives here.” is the book’s second-to-final image, showing a person at work in her studio, a room filled with fascinating and ordinary objects all of which (or nearly all of which?) are found within the other pages in the book—a shoe on the floor (sans bum), the fish bowl, stripy socks. And also sketches of the actual illustrations tacked up to the wall, giving the story a new puzzle along with a metafictional subtext, as well as underlining the message that creative inspiration—even for imaginative journeys to the farthest reaches of the universe—can be found in the ordinary world all around us. Which is certainly a testament to the nature of home, indeed.

February 19, 2015

The magic of First Nations picture books

“That is where change is occurring, when we can appreciate each others’ languages, stories and art.” –Julie Flett, Cree-Métis and Award-Winning Illustrator

“That is where change is occurring, when we can appreciate each others’ languages, stories and art.” –Julie Flett, Cree-Métis and Award-Winning Illustrator

I’ve been thinking a lot about First Nations issues these last few months, and have determined that the one useful thing I can do, in addition to the thinking, is reading. Not just reading either, but actually buying books by First Nations writers, supporting the publishers who support them. Buying and reading books by First Nations women’s writers in particular, and helping to amplify these writers’ voices. I’ve been thinking a lot since reading Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian, about “the dead Indian” and how it was public policy to exterminate First Nations culture (and people) for centuries. And perhaps, less indirectly than you’d think, it still is.

So how does one counter this? Well, by (as I’ve said) buying and reading the work of living, breathing First Nations authors, making these a part of my canon. And then by doing the same with my children, so that it never occurs to them that there is such thing as a Dead Indian. So that they only ever know First Nations cultures as being rich with art and story, with a proud but difficult history. And with the calibre of children’s books being produced these days by First Nations authors, conveying all this is no challenge at all.

What’s the Most Beautiful Thing You Know About Horses?, by Richard Van Camp and George Littlechild

What’s the Most Beautiful Thing You Know About Horses?, by Richard Van Camp and George Littlechild

This book—Richard Van Camp’s second children’s book—was recommended to me when I was raving about Little You. It’s out of print, but I bought a used copy. It begins with Richard asking a simple question one day from his hometown of Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories, where the temperature today is forty below: “What’s the most beautiful thing you know about horses?” It’s a strange, meandering text, perfectly complimented by Littlechild’s illustrations. I like the book because it underlines the fact that First Nations people are undeniably present in the world—we see photos of Richard’s family members, the people to whom he’s asking his question. He’s asking because horses are foreign to his people so far in the north—in his language, Dogrib, the word for horse is “tlee-cho”, which means “big dog.” (‘When did dogs grow into horses? When did horses shrink into dogs? Do horses call dogs “little cousins”?’) He asks the question to his friend, George Littlechild, who is Cree. ‘The Cree word for horses is “mista’tim”. It means “big dog”—just like tlee-cho in the Dogrib language. Isn’t it neat how both our languages call horses “big dogs”?’ Emphasizing that First Nations are NationS indeed—separate but connected, each with its own language and culture. Which is a complicated thing to convey in a story, but Van Camp does it effortlessly. What’s the Most Beautiful Thing You Know About Horses? is a book that takes a single question, and instead of beginning to answer instead opens the world up wide.

Sweetest Kulu, by Celina Kalluk and Alexandria Neonakis

Sweetest Kulu, by Celina Kalluk and Alexandria Neonakis

Published by the award-winning Inhabit Media, an Inuit-owned publishing company located in Iqaluit, Nunavut, the only publisher in the Canadian Arctic, Sweetest Kulu is a sweet lullaby to a beloved baby whose existence is tied to the world all around. “Kulu” is an Inuktitut term of endearment, and indeed, this baby is adored—by the sun with its “blankets and ribbons of warm light,” by Snow Buntings that bring flowers, and by Caribou who “chose patience for you, cutest Kulu. He gave you the ability to look to the stars, so that you will always know where you are and may gently lead the way.” The message of the book, to the baby, is You Belong Here, which is powerful and important for political reasons, but is also an absolutely perfect way to welcome a new baby to the world.

Not My Girl by Christy Jordon-Fenton and Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, and Gabrille Gimard

Not My Girl by Christy Jordon-Fenton and Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, and Gabrille Gimard

Not My Girl is a sequel to the When I Was Eight, both picture books based on the books for older readers, Fatty Legs and A Stranger at Home, memoirs of Margaret Pokiak-Fenton’s experiences at a residential school. In Not My Girl, she returns home to the Arctic after two years at school, and finds she is a stranger to her family, that she has lost her language and taste for her own culture. In a story that’s wholly compelling to young readers, Margaret must rediscover her place in her community and reconnect with her family. Not My Girl makes clear the trauma of children being removed from their families, suggests the painful legacy of residential schools, but ends on an empowering note as she learns to drive her own dogsled as her mother cheers her on.

We All Count: A Book of Cree Numbers, by Julie Flett

We All Count: A Book of Cree Numbers, by Julie Flett

Has there ever been a more subtly subversive title for a First Nations book than We All Count? In this book, which teaches the numbers 1-10 in Cree, Flett celebrates bonds between family and to the land, the illustrations gorgeous and compelling in a style that has become Flett’s signature. Iris, my youngest daughter, is as crazy about this book as she is about Little You. Her favourite image is for “Three aunties laughing.” She likes to point to the picture and tell me, “Happy.”

February 11, 2015

My Julie Morstad story in Quill and Quire

I hope you’ll pick up the latest issue of Quill and Quire, which is on newsstands now. It has a feature on Canadian horror (including a bit with Andrew Pyper, whom I interviewed this week at 49thShelf for his new novel, The Damned, which I really liked) and a huge spotlight on Canadian children’s literature. And right in the centre of the issue is my piece on Julie Morstad, of whose work I am quite beloved—Julia, Child, the Henry books with Sara O’Leary, the award-winning How-To, Singing Through the Dark, and more. The feature includes images from her forthcoming book with O’Leary, This is Sadie, which is going to blow your mind with its goodness. The piece was such a pleasure to write.

I hope you’ll pick up the latest issue of Quill and Quire, which is on newsstands now. It has a feature on Canadian horror (including a bit with Andrew Pyper, whom I interviewed this week at 49thShelf for his new novel, The Damned, which I really liked) and a huge spotlight on Canadian children’s literature. And right in the centre of the issue is my piece on Julie Morstad, of whose work I am quite beloved—Julia, Child, the Henry books with Sara O’Leary, the award-winning How-To, Singing Through the Dark, and more. The feature includes images from her forthcoming book with O’Leary, This is Sadie, which is going to blow your mind with its goodness. The piece was such a pleasure to write.

February 11, 2015

The Lion’s Own Story

A year and a half ago, I fell head over heels in love with the book Ellen’s Lion by Crockett Johnson (who is best known for Harold and the Purple Crayon), a strange and funny book that surely inspired Hooray for Amanda and her Alligator by Mo Willems. It was unusual book, published in 1959 a collection of short stories a bit like the Frog and Toad books by Arnold Lobel or George and Martha by James Marshall, but with more text and fewer illustrations—some pages had no illustrations at all. And I found these stories mesmerizing, so beautiful, hilarious and weird. As Lion is a stuffed toy, all the action takes place in Ellen’s imagination, but as Ellen’s imagination is a thoroughly remarkable place, this doesn’t lessen the stories’ appeal, and they all walk this strange line where it’s never clear where the reality ends and fantasy begins, each one a trick each character is playing on the other. I loved it.

A year and a half ago, I fell head over heels in love with the book Ellen’s Lion by Crockett Johnson (who is best known for Harold and the Purple Crayon), a strange and funny book that surely inspired Hooray for Amanda and her Alligator by Mo Willems. It was unusual book, published in 1959 a collection of short stories a bit like the Frog and Toad books by Arnold Lobel or George and Martha by James Marshall, but with more text and fewer illustrations—some pages had no illustrations at all. And I found these stories mesmerizing, so beautiful, hilarious and weird. As Lion is a stuffed toy, all the action takes place in Ellen’s imagination, but as Ellen’s imagination is a thoroughly remarkable place, this doesn’t lessen the stories’ appeal, and they all walk this strange line where it’s never clear where the reality ends and fantasy begins, each one a trick each character is playing on the other. I loved it.

And I was intrigued to discover that Johnson had published a sequel four years later: The Lion’s Own Story. But I couldn’t find it anywhere. Not a copy to be found in the Toronto Public Library system, nor a used copy to be found online (except for one that was for sale for $300). Which made me wonder if the book was any good—it must not have been in print so long for copies to be so rare, and it’s really unusual for a book to not be anywhere in our city’s huge public library system (which has a special collection for rare children’s books).

But one day in January, I happened to take a look for it online, as I did from time to time, and discovered a copy on sale for $19.00. It wasn’t listed in great condition, which made my husband wary, but I put it to him this way: Would you rather have a crappy copy of The Lion’s Own Story, or never ever get to read it in your life? He saw my point.

Two days ago the book arrived, and the condition isn’t so bad at all. It’s been discarded from the Pacific Grove Public Library in California, which makes it seem like a very exotic arrival in our eyes, even if it smells a bit like a basement. And the stories are really terrific. Perhaps not quite as excellent as those in Ellen’s Lion, but that’s a tall order. It was marvellous to encounter Ellen and her lion again, and I’m going to get to thinking about these books, and write something more about them. Because they’re amazing examples of how smart and fantastic children’s literature can be. And literature too in general.

February 2, 2015

Snow Day Reading Marathon

Today we awoke to a world transformed by snow storm, so we skipped school again and stayed home, ate french toast for breakfast, and staged a Snow Day Reading Marathon. It was pretty wonderful. And tomorrow real life will resume with absolutely no regrets, because we’re all starting to drive each other crazy.

Today we awoke to a world transformed by snow storm, so we skipped school again and stayed home, ate french toast for breakfast, and staged a Snow Day Reading Marathon. It was pretty wonderful. And tomorrow real life will resume with absolutely no regrets, because we’re all starting to drive each other crazy.

January 27, 2015

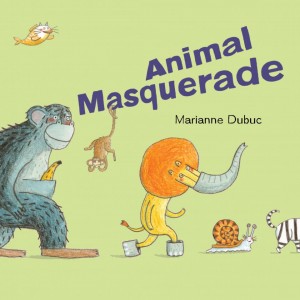

Serendipity, Family Literacy and Animal Masquerade

I don’t know that a family can enforce literacy as much as create the space to let a love of reading just happen. Serendipity plays such a role in it all, as it does whenever anybody discovers a great book. I was thinking about this tonight as I was reading to Harriet from the big pile of books we signed out of the library this afternoon. I was reading Animal Masquerade by Marianne Dubuc, which has been lauded by the likes of Leonard Marcus AND Julie Booker. I’d never read it before, and was enjoying it, and so was Harriet, the animals in disguise quite funny and a twist every now and again but never quite where you’d expect it. And then Iris wandered in, and climbed up beside us, and Stuart followed soon after, intrigued by the sound of this strange book in which a starfish dresses up as a panther. And two thirds of the way in, we were all in love with the story, finding it wonderful and hilarious, all of us perhaps for very different reasons, but regardless, it worked. It’s hard to find a book that hooks 4 people whose ages range from 1 to 35, but this one did, and it was a wonderful moment. The perfect way to mark Family Literacy Day, and I couldn’t have planned it better if I’d tried.

I don’t know that a family can enforce literacy as much as create the space to let a love of reading just happen. Serendipity plays such a role in it all, as it does whenever anybody discovers a great book. I was thinking about this tonight as I was reading to Harriet from the big pile of books we signed out of the library this afternoon. I was reading Animal Masquerade by Marianne Dubuc, which has been lauded by the likes of Leonard Marcus AND Julie Booker. I’d never read it before, and was enjoying it, and so was Harriet, the animals in disguise quite funny and a twist every now and again but never quite where you’d expect it. And then Iris wandered in, and climbed up beside us, and Stuart followed soon after, intrigued by the sound of this strange book in which a starfish dresses up as a panther. And two thirds of the way in, we were all in love with the story, finding it wonderful and hilarious, all of us perhaps for very different reasons, but regardless, it worked. It’s hard to find a book that hooks 4 people whose ages range from 1 to 35, but this one did, and it was a wonderful moment. The perfect way to mark Family Literacy Day, and I couldn’t have planned it better if I’d tried.

January 13, 2015

Reading Green Knowe

Throughout November we were reading Tom’s Midnight Garden at bedtime, which is one of a handful of favourite books from my childhood that hold up just as well. We all enjoyed it, though perhaps Stuart the most because it was his first encounter with the book. I was pleased because I think Harriet mostly grasped the time travel storyline, or some of it. I had read her Margaret Laurence’s The Olden Days Coat two Christmases ago, and she didn’t understand it at all. “There’s this thing called the present,” I was trying to explain, and she was baffled. Interesting too because while she now understands the concept of time, she actually remembers none of that time—anything that happened when she was three and back is kind of lost to us. We reread My Father’s Dragon last week, which I read her when she was three, and she had no recollection. I wonder if you have to have your own history before you understand that there is such a thing as history, and if a prerequisite to having a history is having begun to lose it.

Throughout November we were reading Tom’s Midnight Garden at bedtime, which is one of a handful of favourite books from my childhood that hold up just as well. We all enjoyed it, though perhaps Stuart the most because it was his first encounter with the book. I was pleased because I think Harriet mostly grasped the time travel storyline, or some of it. I had read her Margaret Laurence’s The Olden Days Coat two Christmases ago, and she didn’t understand it at all. “There’s this thing called the present,” I was trying to explain, and she was baffled. Interesting too because while she now understands the concept of time, she actually remembers none of that time—anything that happened when she was three and back is kind of lost to us. We reread My Father’s Dragon last week, which I read her when she was three, and she had no recollection. I wonder if you have to have your own history before you understand that there is such a thing as history, and if a prerequisite to having a history is having begun to lose it.

Anyway, Tom’s Midnight Garden was lovely, and meaningful not only because I loved it as a child, but because it was the second book I read after Harriet’s birth, so to bring back memories of that time with a girl who seems so big now was remarkable. That she’s getting the time travel thing also means that we will be able to read Charlotte Sometimes by Penelope Farmer, which I am so looking forward to—I want to get the New York Review Edition. And at the back of Tom’s… was (in addition to an ad to join the Puffin Club, which I kept trying to join as a child, but I was sending in offers from the back of decades-old books so it never worked) listings of other Puffin books we might like. Including Lucy M. Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe.

I never read The Children of Green Knowe as a child, but received it as a gift about ten years ago, and read it then. I didn’t really get it. But I kept my copy of the book because it had been a gift, and because so many people are crazy about it—I decided there had to be more to it. It seemed in keeping with some of the themes of Tom’s Midnight Garden, the Puffin people thought we’d like it after all, and it’s a Christmas book and this was at the beginning of December. So I proposed we read it en-famille, post-Tom and we did, and it was a remarkable success. For me, in particular. For it seems a book that was meant to be read aloud, and in pieces, rather than plowed through like something with a plot. Reading it this way, I was able to appreciate its magic, its weirdness, and we were all quite struck by its atmosphere.

And it reminded me of the thing that children’s books have taught me about literature and books in general—that there is no such thing as “the text”. The text is ever changing, and its effects depend on myriad factors—the weather out the window, the plushness of a chair, whether or not the reader is awaiting test results. Children’s books, which we read over and over again like no other kind of book, have taught me to ever-undermine my (and any) literary authority. The number of times I’ve flipped through a picture book dismissively, and then sat down to read it with Harriet or Iris, and their appreciation has to directed me to what the book is all about, to what I may have missed the first time. There are bad books for sure, but so often there are great books but I’m just reading them wrong. So what a pleasure is rereading then, for the chance to finally get it right.