September 4, 2015

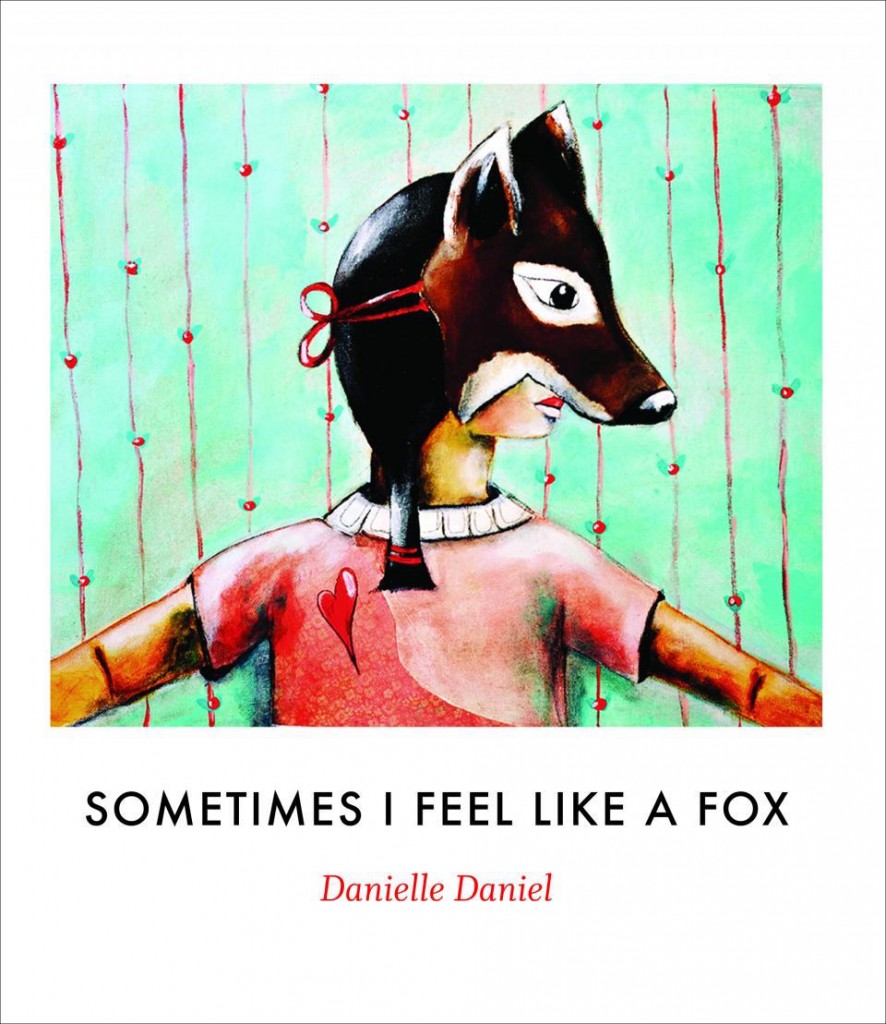

Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, by Danielle Daniel

Today’s Picture Book Friday pick is Sometimes I Feel Like A Fox, by Danielle Daniel, a gorgeous book that my kids love whose meaning is made all the more poignant by its dedication: ““to the thousands of Metis and Aboriginal children who grew up never knowing their totem animal.” Our world is a very complicated place, but I continue to maintain that one very simple thing we can do toward reconciliation with our Metis and First Nations peoples is ensure that our children know their stories, and not just the stereotypes they encounter in so much of classic children’s lit or the “dead Indian” tropes that Thomas King presents in The Inconvenient Indian. And one thing we can do toward healing and ameliorating the status of Indigenous women in Canada is to buy their books, have their stories told. (See the list: Books by Canadian First Nations and Inuit Women.) And so to those ends, picking up a book like this is an important political act.

It’s also a most rewarding literary one.

August 27, 2015

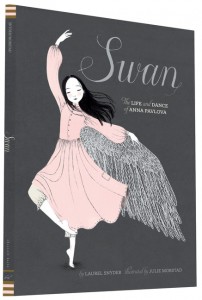

Swan, by Laurel Snyder and Julie Morstad

The thing about a book illustrated by Julie Morstad is that you’ve just got to buy it, because Julie Morstad books are an occasion, the occasions not at all diminished by the fact that she’s been very prolific lately and her books coming out every few months now. (Recently: Julia, Child; This is Sadie.) I’ve been particularly looking forward to her collaboration with Laurel Snyder, because I’ve been an admirer of Snyder (who is pretty prolific herself) since before she’d ever written a book, when I was an avid follower of her long-ago blog (except then we called ourselves readers and not followers). I even have a copy of her 2007 poetry collection (for grown-up people), The Myth of the Simple Machines, whose cover image is more than a little Julie Morstad-esque.

The thing about a book illustrated by Julie Morstad is that you’ve just got to buy it, because Julie Morstad books are an occasion, the occasions not at all diminished by the fact that she’s been very prolific lately and her books coming out every few months now. (Recently: Julia, Child; This is Sadie.) I’ve been particularly looking forward to her collaboration with Laurel Snyder, because I’ve been an admirer of Snyder (who is pretty prolific herself) since before she’d ever written a book, when I was an avid follower of her long-ago blog (except then we called ourselves readers and not followers). I even have a copy of her 2007 poetry collection (for grown-up people), The Myth of the Simple Machines, whose cover image is more than a little Julie Morstad-esque.

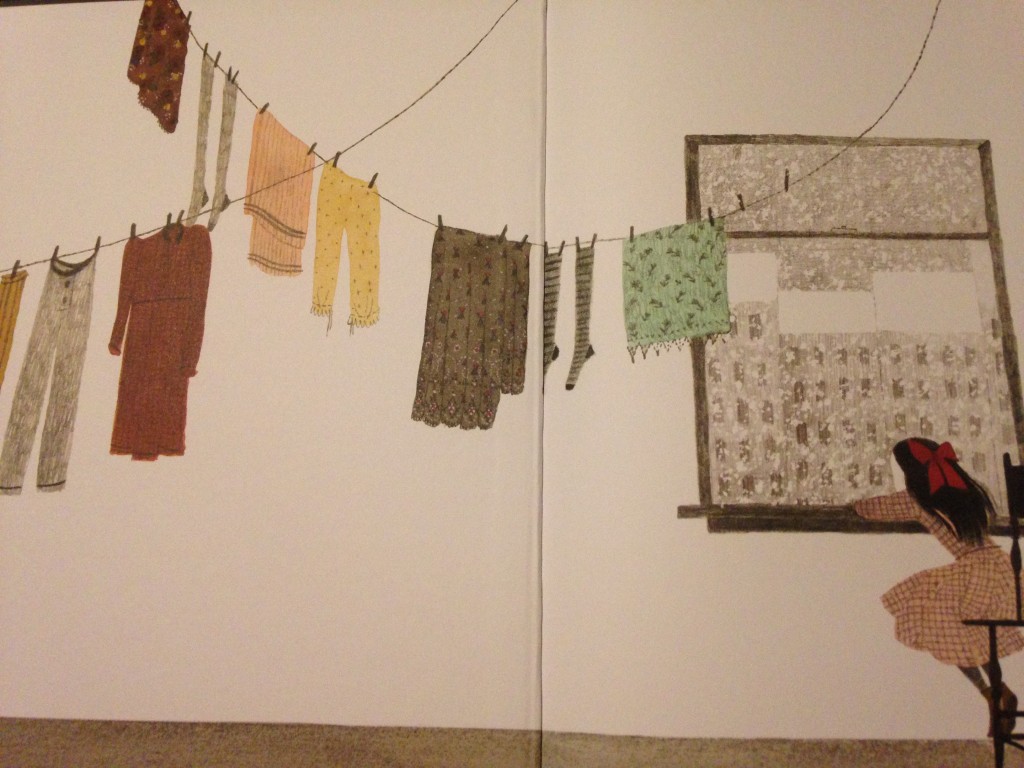

Morstad and Snyder’s collaboration, Swan, is a picture book biography of the ballerina, Anna Pavlova.

For anyone with a thing for laundry lines in literature (and there are many of us!), this book is for you. It’s the story of a young girl (born in 1881, as the note from the author at the end informs us) whose world is transformed when her mother takes her to see Sleeping Beauty at the ballet.

“Now Anna cannot sleep. Or sit still ever.” Even as she works with her laundress mother, she is thinking about dancing. “She can only sway, dip, and spin…”

The route to success is not so direct. Anna does not get into ballet school on her first try. Once she is admitted (“The work begins. The work? The work! Up and down and back and turn and on and on… Again! Again! Again!”), it is generally assumed that she does not have the right body type, too strange feet for ballet. But she flourishes. Five years into her career, she dances her most famous role: The Swan.

Swan reminded me of Barbara Cooney’s Miss Rumphius, the story of a young woman with fierce ambitions who also wishes to make the world more beautiful. Anna Pavlova does this not by planting lupines, but by bringing her art to people around the world who’d never before had access to the elite world of ballet. “Across bullrings and the warped boards of dance halls, she moves everyone. The sick and the poor come to meet her boats and trains, they cheer her, and are cheered.”

I love the fashion (that cloche hat!) in Morstad’s illustrations, and the gorgeous costumes. I also love the footsteps in the snow, which reminds me of Singing Away the Dark, by Caroline Woodward, one of my favourite Julie Morstad titles. Snyder’s prose is full of its own kind of music, sound and rhythm, repeating patterns, a contrast of soft and quiet tones, the reader wholly engaged in the narrative. It’s a book that begs to be read aloud: “There’s a swell of strings, a scurry of skirts. A hiss and a hum and… HUSH! It’s all beginning!”

Full disclosure necessitates that I tell you that Harriet isn’t quite as mad for this book as I am. She admires much about it, but says she finds the ending much too sad. While I really love the ending, how Anna Pavlova’s death is represented as another beautiful performance. (The author’s note explains that Pavlova was calling for her swan dress in her fever.) I appreciate that death is necessarily part of the story, and how gorgeously Snyder puts it: “Every day must end in night. Every bird must fold its wings. Every feather falls at last, and settles.”

“Can I still read it anyway?” I ask Harriet, and she says I can.

I have a feeling it’s going to grow on her.

August 13, 2015

Three New Books About Loss

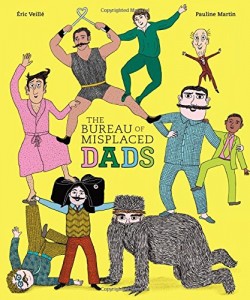

The Bureau of Misplaced Dads, by Eric Veille and Pauline Martin

The Bureau of Misplaced Dads, by Eric Veille and Pauline Martin

This book has a vintage vibe right down to its oranges, greens and yellows, the crosshatching, and that the illustrations remind me so much of Esphyr Slobodkina’s Caps for Sale—perhaps it’s the moustaches? It also is completely weird in that way picture books got away with back in the day. Utterly pointless, silly, absurd, and I mean it in the best way. (Maybe it’s just European?) It’s about a boy who loses his dad one morning and finds assistance at the Bureau of Misplaced Dads, where lost fathers go to wait for their children to retrieve them. (Most are in fairly good condition when they’re finally found.) Some are found same day, others have been waiting since the dawn of time. “The dads in striped sweaters hang out in the Ping-Pong room.” They aren’t allowed to play with the crocodiles, but otherwise they can do anything they please. There are two full-page spreads that are totally Wild Rumpus-inspired. The ending will satisfy anxious readers, but is just as strange as rest of it, which is to say that it involves a short cut in which the boy climbs up the ladder beside an old dog, and arrives home via a hole in the floor. Hooray for short-cuts, and books rich with strange surprises.

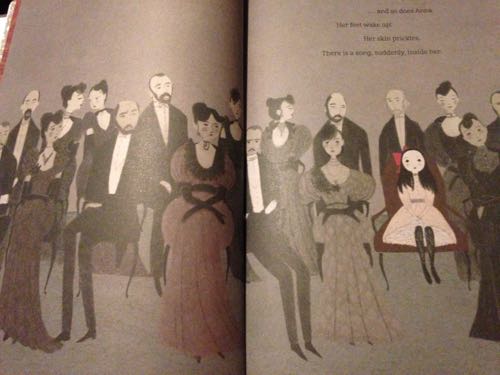

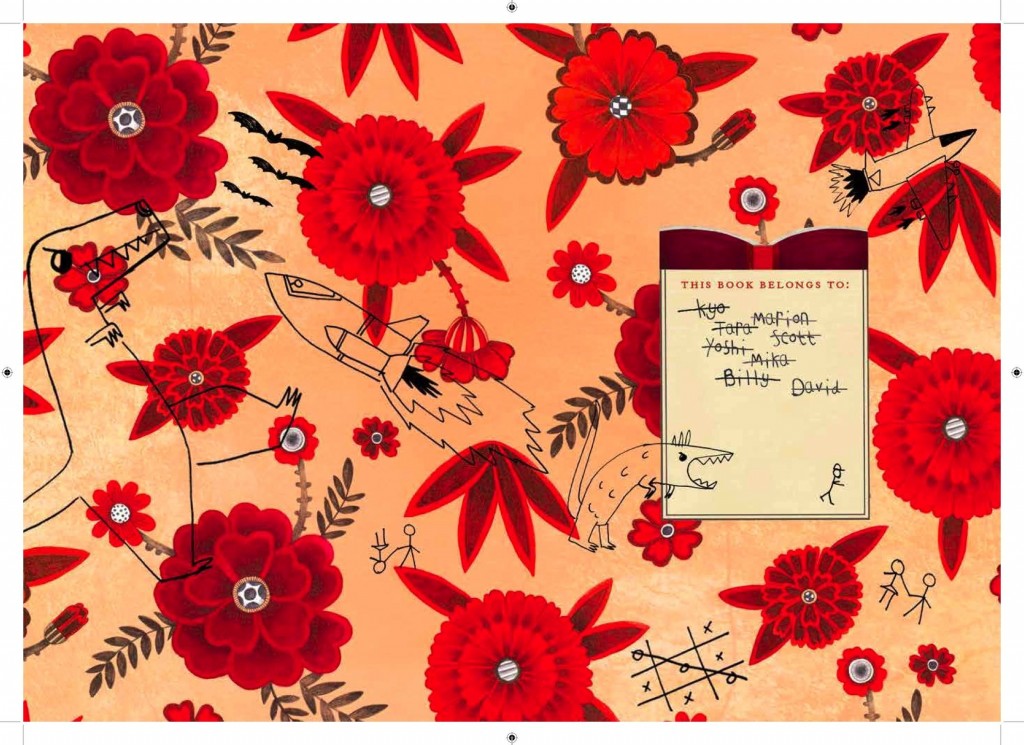

The Good Little Book, by Kyo Maclear and Marion Arbona

The Good Little Book, by Kyo Maclear and Marion Arbona

I was rhapsodizing about Kyo Maclear a couple of weeks back because she’s managed to have two books out this fall that are very different and both excellent—she’s so good! The Good Little Book is a gorgeous package, its deliberate graffiti’d bookplate and endpapers, the whole thing beautifully designed to emphasize the book as object, which connects to the story. About one book in particular that is “neither thick nor thin, popular nor unpopular. It had no shiny medals to boast of. It didn’t even own a proper jacket.” (Get it? Jacket?) But this little book finds its way into one reader’s heart, and there it stays, accompanying the reader everywhere, changing his life. Until one day the book gets lost. The boy who lost it fearing for his book in the wild, seeing as it doesn’t even have a jacket. (Ha!) But a good book, the boy learns, never really goes away, and the book itself, we learn, continues to be loved and read, as good books do. “Is this the end of the book?” is the question inked upon the final pretty floral endpaper, to which this reader knows the answer: never!

Some Things I’ve Lost, by Cybele Young

Some Things I’ve Lost, by Cybele Young

As one who has long been intrigued by the secret lives of things, I’m intrigued by Cybele Young’s new book, which is inspired by her paper sculptures. A set of keys, a roller skate, an umbrella (and I do have a fascination with literary lost umbrellas), a pair of glasses. Things that disappear (and I’ve written about that too). But: “Where there’s an end there’s a beginning,” Young’s book’s introduction tells us. “Things grow. Things change.” The books’ transformations are abstract enough as to be unpredictable and engaging, and budding artists might be inspired to make their own “some things” new.

July 24, 2015

This Specific Ocean by Kyo Maclear and Katty Maurey

The first thing I ever read by Kyo Maclear was The Letter Opener, a novel, which I loved, and so it’s taken some time to get my mind around the idea of her as a picture book author. Even though the books themselves were very good—the brilliant Spork, and the strange and beautiful Virginia Wolf, and the even-stranger Mr Flux that has grown on us so much that I routinely pick it up and read for comfort in times of anxiety (“Sometimes change is just change”). I should have twigged to something with the amazing Julia, Child, her collaboration with one of my favourite illustrators, Julie Morstad. But no, I thought. These were just ones-0f-a-kind. Brief flourishes of excellence. No picture book writer could keep producing work that is every time so different, so smart in its concept, original and singular—each book its own perfect world. But Kyo Maclear does, and it’s so remarkable. I’m convinced finally as this fall she has two extraordinary releases, The Good Little Book, illustrated by Marian Arbona, and this one, The Specific Ocean, with Katty Maurey.

Maclear has been fortunate in her picture book career to work with some of Canada’s best illustrators, Isabelle Arsenault and Morstad among them, ensuring that her books have considerable visual appeal. Indeed, when the books have won awards, it has tended to be for their illustrations, and my own focus on her book’s images has contributed to my reluctance to give Maclear full credit for her picture book prowess, though I have long been a huge fan of her work. But with her two most recent books—each so different in illustrations and design, and so different too from her previous works—I’ve really finally come on board. In all her stunning books with their own particular style, Maclear herself is the common denominator. And she’s come far enough in her career that we can start to marvel at her oeuvre.

But, as the title suggests, it’s time to get specific, and Maclear’s work is so various that specifics are the most interesting way to discuss it. The Specific Ocean is about a young girl whose family is flying across the country for their summer vacation, but the girl doesn’t want to go with them. She wants to stay in the city and play with her friends, so when they finally do arrive at their destination beside the sea, she is resolute in her misery and refuses to enjoy herself.

It’s the ocean that finally sways her though, its formidable coldness, the spots of warmth: “We float on our backs, and the wind blows ripples across the water’s surface, and those ripples grow into waves that life us up and up.” She begins exploring the wonders of the beach, birds and shells and tide-rolls. “When the sun comes out, we sit on the rocks and watch the waves. Shine, shimmer. gleam, glow. It makes me dizzy to imagine where the sea ends. The ocean is so big that it makes every thought and worry I have shrink and scatter.”

As with all of Maclear’s books, complex ideas are presented through scenarios with which a young reader would be familiar. The effect is subtle—my daughter would not notice that she’s reading anything but a story about a girl who travels to the seaside. But she might notice that this is very different than other books about trips to the seaside. In a deceptively simple narrative package, Maclear is addressing issues of anxiety, of anger, of wonder, of emotions, of the power and knowledge that comes with growing and learning and changing one’s mind.

The girl learns to embrace the ocean, but with that comes a new anxiety. For how does one embrace an ocean after all? With something so huge, how do we wrap our arms around it? How do we love things that are much too big to hold? The girl comes up with scenarios involving putting the ocean in a bowl, carrying part of it home with her. But her wise older brother counsels her otherwise: “[he] says if I do that, the ocean will be less. He says the ocean may be big, but it isn’t endless.”

By the end of the vacation, the girl doesn’t want to go home—of course! Life itself being a tension between two pulls/poles. But she becomes reconciled with her departure by an awareness that the wildness of the ocean, its deep and dark mysteries and lack of containment, are most essential to what she loves about it. And that this same spirit and complexity she carries within herself: “Calm. Blue. Ruffled. Gray. Playful. Green. Mysterious. Black. Foggy. Silver. Roaring. White.”

Which means she’s not leaving it behind at all.

July 16, 2015

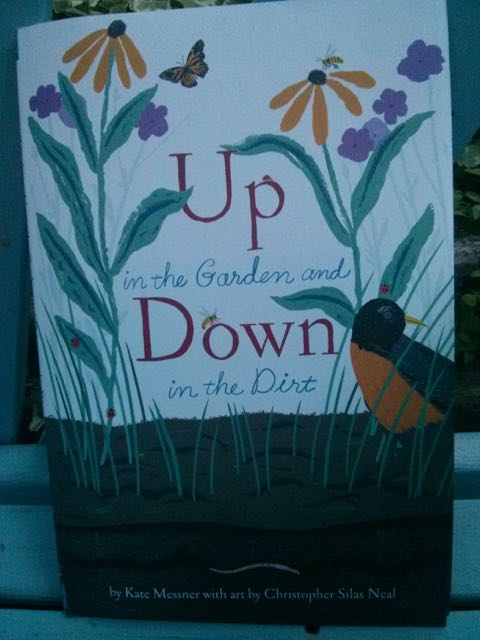

Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt

We went to Parentbooks today to buy a birthday present for Harriet’s friend, and their gorgeous summer books table drew me right in. We ended up buying Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt, by Kate Messner and Christopher Silas Neal, because it seemed a wonderful companion to Weeds Find a Way, because the illustrations are gorgeous, and because it was so perfectly in tune with our familial zeitgeist of late, which is all butterflies (which Iris calls “fuff-eyes”), watering cans, weeding, and getting up to our elbows in soil.

The story begins in the springtime, the earth just waking up and the crocuses poking through. Neal’s illustrations show that it’s not just up in the garden where the action is happening, but that underground a whole world exists that helps the plants to flourish.

My favourite thing about the book is how the illustrations convey the momentum of the summer garden, which is never the same two days, one plant replacing another. From crocuses, to forsythia, to magnolias, to lilacs, to irises, to linden blossoms, and onto cosmos. It’s like time, spilling over, uncontainable. The kind of thing I never noticed before I started paying attention.

Messner shows the garden as a place of fun and play as well as labour, her young protagonist cooling off from the summer heat by being sprayed by her Nana’s garden hose. While, “Down in the dirt, water soaks deep. Roots drink it in, and a long legged spider stilt-walks over the streams.”

The silhouettes at the end are particularly striking, showing that the nocturnal world—bats!—has its own role to play in helping with the garden. On the next page, there is even a skunk, an animal which—according to the book’s fascinating glossary—is actually a garden helper. Who knew? “Like bats, skunks are nighttime predators that gobble garden pests after dark. Skunks love grubs and slugs.” Ants too—I had no idea. They help to pollinate plants and air the soil with their tunnelling. Harriet and I were both gripped by these facts. It is nice to find a book that can teach new things to two readers who are thirty years apart.

By the end of the book, it is fall, harvest time. Much of the action is taking place underground again, as the pumpkins are nearly ready and the cold is near. And in winter, the story tells us, “a whole new garden sleeps down in the dirt,” the tunnels and nests and animals and insects underground drawn to resemble flowers and vines in an abstract sense—pictorial subtext. It’s wonderful.

Wonderful too the way that the book makes the connection between gardens and books and reading so clear.

July 14, 2015

Nature is as careless as it is bountiful

“For nightmare, you eat wild carrot, which is Queen Anne’s lace, or you chew the black stamens of the male peony. But it was too late for prevention, and there is no cure. What root or seed will erase that scene from my mind? Fool, I thought; child, you child, you ignorant, innocent fool. What did you expect to see—angels? For it was understood in the dream that the bed full of fish was my own fault, that if I had turned away from the mating moths the hatching of their eggs wouldn’t have happened, or at least would have happened in secret, elsewhere. I brought it upon my self, this slither, this swarm.

“For nightmare, you eat wild carrot, which is Queen Anne’s lace, or you chew the black stamens of the male peony. But it was too late for prevention, and there is no cure. What root or seed will erase that scene from my mind? Fool, I thought; child, you child, you ignorant, innocent fool. What did you expect to see—angels? For it was understood in the dream that the bed full of fish was my own fault, that if I had turned away from the mating moths the hatching of their eggs wouldn’t have happened, or at least would have happened in secret, elsewhere. I brought it upon my self, this slither, this swarm.

I don’t know what it is about fecundity that so appalls. I supposed it is the teeming evidence that birth and growth, which we value, are ubiquitous and blind, that life itself is so astonishingly cheap, that nature is as careless as it is bountiful…” –Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Although Dillard concedes that fecundity is not quite so appalling with plants. She goes on to report, with amazement, a fifteen-foot-long tree growing from the corner of a garage roof, “rooted in and living on ‘dust and cinders.'” I had forgotten about her relative comfort with, her admiration for exploding botanicals, because it’s around this time of the summer every when I spy life coming up through the cracks in the sidewalk that I think about her comment on the appallingness of fecundity—something awful in both senses of the word. When summer throws off its harness, asserting the wild. We are no tamers of it, any of us, and concrete is only incidental. The whole world is bursting with green.

Although Dillard concedes that fecundity is not quite so appalling with plants. She goes on to report, with amazement, a fifteen-foot-long tree growing from the corner of a garage roof, “rooted in and living on ‘dust and cinders.'” I had forgotten about her relative comfort with, her admiration for exploding botanicals, because it’s around this time of the summer every when I spy life coming up through the cracks in the sidewalk that I think about her comment on the appallingness of fecundity—something awful in both senses of the word. When summer throws off its harness, asserting the wild. We are no tamers of it, any of us, and concrete is only incidental. The whole world is bursting with green.

Though I am not sure there is anything careless about it. I have never encountered a force more determined.

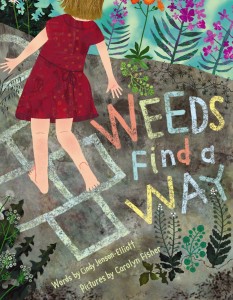

So it seemed like as good a time as any to get Weeds Find a Way out of the library, a book I recall hearing about last year when it came out but hadn’t read yet. The writer, Cindy Jensen-Elliott as full of wonder and amazement as Dillard is when it comes to the tenacity of weeds, their adaptive knack. Carolyn Fisher’s illustrations are beautiful, the book’s unique design bringing text and images together in a playful, gorgeous and illuminating experience. A glossary at the end of the book highlighting a number of common weeds, weeds so common as to be obscure if (to steal a line from poet Mary Ruefle via Heidi Julavits in The Folded Clock) “we can extend the meaning of obscure to be mean covered up by dailiness.” And who doesn’t love a book with a glossary?

So it seemed like as good a time as any to get Weeds Find a Way out of the library, a book I recall hearing about last year when it came out but hadn’t read yet. The writer, Cindy Jensen-Elliott as full of wonder and amazement as Dillard is when it comes to the tenacity of weeds, their adaptive knack. Carolyn Fisher’s illustrations are beautiful, the book’s unique design bringing text and images together in a playful, gorgeous and illuminating experience. A glossary at the end of the book highlighting a number of common weeds, weeds so common as to be obscure if (to steal a line from poet Mary Ruefle via Heidi Julavits in The Folded Clock) “we can extend the meaning of obscure to be mean covered up by dailiness.” And who doesn’t love a book with a glossary?

“Wild carrot (Daucus carota) is also known as Queen Anne’s lace. It is said to have gotten its nickname when Queen Anne of England visited Denmark and challenged the ladies there to create lace as fine as the flower of the wild carrot.”

“Wild carrot (Daucus carota) is also known as Queen Anne’s lace. It is said to have gotten its nickname when Queen Anne of England visited Denmark and challenged the ladies there to create lace as fine as the flower of the wild carrot.”

Which you can also eat for nightmare, apparently. Who knew?

July 2, 2015

The Princess and the Pony by Kate Beaton

We’re all besotted, each of the four of us, who are aged from 2-36, but we’re confident that even those beyond our expansive age-range could find much to love in Kate Beaton’s debut picture book, The Princess and the Pony.

Because it’s got everything! Princesses, yes, and ponies, and farting, and burly Vikings married to powerful Amazons (and they hang celebratory bunting in their house). Knights and battles, and more farting, dodgeballs, spitballs, hairballs and squareballs (those were new). “In a kingdom of warriors, the smallest warrior was Princess Pinecone. And she was very excited for her birthday.” Is the beginning of a picture book that gets kids exactly right.

Not being a kid, the things I notice are a little bit different. Like that Princess Pinecone is mixed-race and that her mother looks like a Black Wonder Woman. I love the book’s acknowledgement that sometimes adults don’t get things right and that life can be disappointing. I love Princess Pinecone’s persistence, her optimism, her courage. I love that this is the least-gendered book called The Princess and the Pony ever.

The Princess and the Pony is a book that shows us that appearances can be deceiving, that power comes in many different forms, that most of us have a cuddly side, and that farts are the only thing we can ever really count on. But most importantly, it is ridiculously fun to read. Kate Beaton has followed up her runaway smash hit, Hark a Vagrant, with a book that’s only nominally for a different audience. Everybody’s going to like this one too.

We’re looking forward to seeing Kate Beaton at The Princess and the Pony Launch Party on Saturday! Details here.

June 26, 2015

My Favourite Things and Ah-ha to Zig-Zag by Maira Kalman

In 15 years of blogging, I am not sure there’s a post I’m more proud of than the one I wrote last fall about my accidental discovery of the artist Maira Kalman (and of how that led to cake). Coming to Maira Kalman was a curious experience rich with signs and wonders, like the United Pickle label on the back of The Principals of Uncertainty, and the title of the book at all because I would have purchased any volume called such a thing. Not to mention that hers are picture books for grown-ups, which I so completely delight in, and so I was thrilled to receive for my birthday yesterday a copy of her book, My Favourite Things.

“Isn’t that the only way to CURATE A LIFE? To live among things that make you GASP with delight?” Kalman writes, which is just one of the many points at which this book had me nodding and gesturing emphatically. And yes, GASPing with delight.

My Favourite Things is as random as its title suggests, art and writing about various objects. Part 1 is “There Was a Simple and Grader Life,” which explores Kalman’s family history through items including a grey suit belonging to her father, a grater for making potato pancakes, and her aunt’s bathtub in which fish would swim “waiting to become Friday Night dinner.” Part 3 is called “Coda: or some other things the author collects and/or likes” (including “bathtubs, buttons and books”) and the middle section of the book was born from Kalman’s experience curating an exhibit of her favourite items from The Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum.

My children were excited to realize that they recognized many parts of the second section of my new book, because I’d bought them a copy of Kalman’s children’s book Ah-hA to Zig-Zag last December.

It was a book they had some trouble with at first because Kalman’s zaniness is a bit lost on the childhood mind which is so often looking for things to make sense and for books to have stories. But Kalman’s unorthodox A-Z (which, like My Favourite Things, is also a tour though objects from her exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt ) grew on them, and they can appreciate its strangeness now that it’s familiar (and they like the image of the cutest dog on earth, as well as the picture of the toilet in the middle of the alphabet—”Now might be a good time to go to the bathroom. No worries. We will wait for you. Not a problem.”—as a bathroom visit is essential to any museum experience [although it’s curious that she never makes it to the cafe.])

(As a notorious imperfectionist, I am also partial to O.)

Not only do Kalman’s books celebrate the marvellousness of things, the books themselves are marvellous things in their own right. They’re things that (literally) speak to you (Ah-hA! There you are. Are you ready to read the Alphabet?…), and unless I’m particularly singular (unlikely) you too will find that Kalman’s curated collections will speak to you in other ways too, connecting with your experience in an uncanny manner, making you suspect that Kalman’s been eavesdropping on your soul.

The only trouble with the overlap between Ah-Ha! and My Favourite Things is that my youngest daughter keeps getting frustrated by being unable to find the toilet in the latter, though that is just another example of how these beautiful puzzling books are so wholly engaging. Having a few of them lying around the house is not a bad to curate a life after all.

June 19, 2015

Butterfly Park by Elly Mackay

I bought Butterfly Park because Sara O’Leary named it as a hypothetical Sadie Summer Read in our 49th Shelf interview, and then I saw it featured on the wonderful children’s literature website, kinderlit. When I finally laid eyes on on the actual book, it was inevitable that we’d own it. It’s beautiful, magical, and infused with the same sense of wonder that is so compelling about This is Sadie.

The story is simple, and not really ground-breaking: a young girl moves from the lush countryside to a dank and dirty town. The one spot of hope is a park beside her house with an elaborate gate and a sign reading, “Butterfly Park.”

But when the girl goes inside, there is not a butterfly to be found. With the help of other children in the neighbourhood, however, the girl embarks upon a quest to make Butterfly Park live up to its name, and the whole community is awakened in the process.

While the story is pretty basic, the book’s depth comes from its illustrations—literal dept and otherwise. Mackay’s images are extraordinary, paper cut-outs painted and assembled in three dimensional scenes in a wooden frame, and then photographed. There is a an old-fashioned Victorian postcard feel to the children she has painted, except that her children show diversity in their skin colours, which is wonderful. And it’s remarkable to consider that her exquisite detail has been rendered in paper cut-outs—I’m especially fond of her clotheslines, garden gnomes, and all the other perfect little things in the corners of her scenes.

My favourite thing about Butterfly Park is MacKay’s rich and warm use of light, which indicate the passage of time and time of day. Her glowing oranges and yellow are beautiful to behold and add event more texture to this images, if such a thing is possible.

I also appreciate how my daughter’s response to reading the book was a very This is Sadie-like move to go out and make something. “Mom, I need the scissors,” she said, and got to work cutting out bits of paper in a way she hadn’t done since she was three (which, if you are a parent, you will know is most children’s peak cutting-out-bits-of-paper period). I also love how the book’s conclusion underlines things I’ve been thinking about lately about gardening as community building.

Plants need roots to grow, indeed.

June 11, 2015

Harriet, You’ll Drive Me Wild by Mem Fox and Marla Frazee

Okay, can we just stop for a moment while I tell you how I worship at the feet of Marla Frazee‘s entire career? The woman behind some of the great picture books ever—Everywhere Babies, The Seven Silly Eaters, and All the World. Her own books too—Roller Coaster and The Farmer and the Clown. Her images are so vibrant, complex, textured, diverse, her world so detailed, her babies so perfect, and her toddlers so perfect…ly devious. I love her. I love her. I do.

I read somewhere once (or else I dreamed it?) that Marla Frazee was not the original illustrator for Harriet You’ll Drive Me Wild, and that there exists somewhere a completely different edition of this book. I am unclear as to the veracity of this rumour not just because I can’t find a single shred of evidence supporting it, but more because it seems unfathomable. (Update: but it’s true! The book was first published in 1986 as Just Like That, illustrated by Kilmeny Niland.)

My neighbours gave me their old copy of this book (the 2003 edition) when my Harriet was three weeks old. I remember sitting in the chair by the window, the scene of innumerable struggles to get the baby to latch, and how here was a book very different than the others we’d been reading in that storm. Different from the new parenting books I’d already filled with my manic marginalia, and different from the baby board books with their saccharine endings (which were somehow always about going to sleep. I wondered, when was that part going to happen?). Here was a book that gave me a glimpse of the future, of a time in which my new baby might not be small enough to tuck in neatly across my chest as we napped on the couch—shocking. A glimpse of a child-to-be, full of energy, beans and mischief.

Where Fox’s Harriet was once my future, six years later, she’s now the past. The character is about three, I think, not intending any trouble (which, according to the text, always happens “just like that”). Frazee’s images show another reality, however, of squirms, experiments, curiosity, contortions and shenanigans—but still, she can’t help herself. “Harriet Harris was a pesky child. She didn’t mean to be. She just was.”

There are so many things I love about this book. First, that it’s Mem Fox, whose work has been so essential to my happiness as a parent. (Read Where is the Green Sheep and not be happy. I dare you.) Second, it’s a literary Harriet, and we love these. Third, that it depicts a very realistic mother, a bit frumpy and struggling to get her own things done while her daughter thwarts her at every turn. (I imagine that between the pages, she is ignoring her daughter and scrolling through Twitter.) And shows that a mother can get angry (for good reason) but that this is okay. Things—people and pillows—can explode, but that doesn’t mean that it can’t be made all right again.

But the foremost reason I love this book is because of the text, and how the lines build on one another along with the mother’s frustration. She begins with her patience tested, saying (because she doesn’t like to yell), “Harriet my darling child. Harriet, you’ll drive me wild.” And that added on to that by the end is, “Harriet, sweetheart, what are we to do? Harriet Harris, I’m talking to you.” Delivered in harassed mother voice. The alliteration of the name is delicious to say, along with the rhyme. I love the consternation.

Reading the part of a mother in a book is rarely quite so nuanced and interesting.