October 30, 2015

Missing Nimama, by Melanie Florence and François Thisdale

It’s not my usual practice here to write about a picture book that I haven’t read with my children, but Missing Nimama, by Melanie Florence and François Thisdale, is not your usual picture book. And I didn’t read it with my children not because they don’t know about Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Girls and Women—indeed, my 6 year old does know about this terrible part of our country’s colonial legacy, a legacy that’s lasted right up to this exact second—but because she told me she didn’t want to read a story that was sad. And neither did I, truthfully, to have to give voice to this story’s achingly, awful, beautiful words: the words of a mother who has been lost to her daughter but watches over her still, and the words of a daughter who has to grow up without the mother who loves her oh so much.

Stories of children who’ve lost their mothers are perhaps the most unbearable thing I can contemplate. So I don’t, usually. But in the case of Missing Nimama, I was compelled to read on, spurred on by Thisdale’s gorgeous dreamlike illustrations (which are similar in effect to his work in the acclaimed The Stamp Collector). I was also drawn by the story, written by Cree writer and journalist Florence. Her young character, Kateri, is raised by her loving maternal grandmother, who tells her that her mother is lost:

‘”If she’s lost, let’s just go and find her.”

Nohkom smooths my hair, soft and dark

as a raven’s wing.

Parts it. Braids it. Ties it with a red ribbon,

My mother’s favourite colour.

“She’s one of the lost women, kamamakos.”

She calls me “little butterfly.” Just like my nimama did.

Before she got lost.’

And then we hear nimama’s voice: “Taken. Taken from my home. Taken from my family. Taken from my daughter. My kamamakos. My beautiful little butterfly. I fought so hard to get back to you, Kateri. I wish I could tell you that. And when I couldn’t fight anymore, I closed my eyes. And saw your beautiful face.”

We see Kateri growing up, thriving under the loving care of her grandmother, and under the proud watchful eye of her mother. We see her grappling with her loss and grief, learning about her culture and traditions, growing up and finding her way in the world. And the heartbreaking sadness of the story is balanced by Kateri’s success in her life—the stability she finds as she grows older, gets married, has a child of her own. A stability that is against the odds, perhaps, and I think about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in connection with the history of Residential Schools and how many social problems in First Nations communities are results from over a century of cultural genocide. Not to mention the much more direct instances of government-sanctioned violence against Indigenous women in Canada.

I think of all these children who’ve lost their moms.

I don’t think that children like mine are necessarily who this picture book is meant for, not right at this moment in time, perhaps. For the far too many children for whom this story is close to home, however, I can’t imagine how powerful it would be to see one’s own experience reflected in a story like this, Kateri’s own story an inspiring example of the path a life can take, even one that begins with incalculable loss and trauma. (Which is not to say that this isn’t an important story for anyone—it’s such a visually compelling book that I’d like to keep it around, have my children leaf through, and become familiar with. We will definitely read it together. We’ll just have to ease our way into it…)

But then, someone might ask, why is it a picture book after all? Surely a book with such subject matter should be geared toward older readers? Should be a chapter book, at least? To which I respond that picture books have nothing to do with age. That grief and trauma don’t have a minimum age requirement either, sadly. That picture books allow this story to be accessible to all kinds of readers (and, remarkably, like all books from Clockwise Press, this one is printed in a “dyslexia-friendly” typeface). And most of all, that this story works because it’s a picture book, because of the marriage of words and stories, and how the respective voices of mother and daughter can exist together, even if apart, on the page.

Missing Nimama is a mourning song, but also a call to action. Near the end of the story, Kateri attends a public vigil for missing and murder aboriginal women: “Stolen sisters. I hold my own sign. My own lost loved one.” And the book’s final page contains quotations by family members of murdered women, from the UN Report which dictates that “Canada must take measures to establish a National Public Inquiry into cases of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls.” And our soon to be ex-Prime Minister’s infamous shameful view on the subject: “It isn’t really high on our radar, to be honest.”

The numbers are important, inarguable. “A total of 1181 Indigenous women and girls have been murdered or went missing between 1980 and 2012.”

But it’s going to be stories—like that this one—that make the difference if we’re to give all of our daughters a chance to live in a better world.

October 23, 2015

The Ghosts Go Spooking, by Chrissy Bozik and Patricia Storms

This week our family has been having fun with The Ghosts Go Spooking, a new picture book written by Chrissy Bozik and illustrated by my friend, Patricia Storms. Sung to the tune of The Ants Go Marching, the story traces the antics as a group of friendly ghosts make the most of Halloween night on their way to a costume party at a haunted house. A nice touch is that the ghosts themselves are costumed—as a clown, a witch, a cowboy. As as they go, one-by-one, two-by-two, etc., one of them (a different one every time—the scary one, the silly one, the wiggly one) stops and does a variety of things—knockings on a door, does a jive, does some tricks.

The story is more fun than scary, which is a good thing with our crowd, and my kids like the mischief the ghosts get up to, their amusing extra-textual dialogue in the illustrations: “Better than a rabbit,” exclaims the Bunny-hopping ghost when “the clever one” conjures bats from his hat. Momentum builds as the ghosts eventually end up spooking ten-by-ten, arriving at their party to find a horn-playing werewolf and a vampire on the double-bass, spooky rock-and-rolling against an enormous yellow moon. No doubt this is a party that will go one well into the night.

Boo boo boo…

October 9, 2015

Written and Drawn by Henrietta, A Toon Book by Liniers

We are in love, besotted, absolutely gaga. I first heard tell of Henrietta—a small brilliant and bookish girl who appears in the Macanudo comics by Argentine artist Liniers—when “Henrietta’s Reading Adventures” appeared in The New Yorker. Then Dan Wagstaff informed me that a Henrietta book was forthcoming from TOON Books, which we’re huge fans of. And that book is Written and Drawn by Henrietta, fun, inspiring and amazingly terrific. We read it together over dinner last night, and just now I had to go retrieve it from Harriet’s bed.

We are in love, besotted, absolutely gaga. I first heard tell of Henrietta—a small brilliant and bookish girl who appears in the Macanudo comics by Argentine artist Liniers—when “Henrietta’s Reading Adventures” appeared in The New Yorker. Then Dan Wagstaff informed me that a Henrietta book was forthcoming from TOON Books, which we’re huge fans of. And that book is Written and Drawn by Henrietta, fun, inspiring and amazingly terrific. We read it together over dinner last night, and just now I had to go retrieve it from Harriet’s bed.

Written and Drawn by Henrietta is a story about the pleasures and frustrations of the creative process. Young readers will be inspired by Henrietta’s creation to make an attempt at their own literary masterpiece (and won’t be intimidated either, with Liniers’ rudimentary-looking Henrietta-style). They will also benefit from practical advice Henrietta offers along the way:

Creating art is not without its challenges and pitfalls, and Henrietta contemplates these as well.

But the narrative is driven primarily by her wonder and her excitement at the story she is creating (“I’m drawing really fast because I want to see what happens next…”) and the reader will be inspired to begin her own creation on Henrietta’s coattails.

…Or at least I’d like to meet the kid who wasn’t.

October 7, 2015

No wonder the children grew peaky

“So he didn’t have your advantages,” went on Homily breathlessly, “and just because the Harpsichords lived in the drawing room—they moved in there, in 1837, to a hole in the wainscot just behind where the harpsichord used to stand, if ever there was one, which I doubt—and were really a family called Linen-Press or some such name and changed it to Harpsichord—”

“So he didn’t have your advantages,” went on Homily breathlessly, “and just because the Harpsichords lived in the drawing room—they moved in there, in 1837, to a hole in the wainscot just behind where the harpsichord used to stand, if ever there was one, which I doubt—and were really a family called Linen-Press or some such name and changed it to Harpsichord—”

“What did they live on,” asked Arietty, “in the drawing room?”

“Afternoon tea,” said Homily, “nothing but afternoon tea. No wonder the children grew up peaky. Of course in the old days it was better—muffins and crumpets and such, and good rich cakes and jams and jellies, And there was an old Harpsichord who could remember sillabub of an evening. But they had to do their borrowings in such a rush, poor things. On wet days, when the human beings sat all afternoon in the drawing room, the tea would be brought in and taken away again without a chance of the Harpsichords getting near it—and on fine days it might be taken out into the garden. Lupy has told me that, sometimes, there were days and days when they lived on crumbs and water out of the flower vases. So you can’t be too hard on them; their only comfort, poor things, was to show off a bit and wear evening dress and talk like ladies and gentlemen…” —Mary Norton, The Borrowers

(We’re reading this right now and I’m loving it so much. I don’t know that I’ve ever read it before. When I was a child, I was into the American knockoff, The Littles, but I had no taste, and Mary Norton is so clever, funny and bright. I also like our copy because the cover is by Marla Frazee, who is one of my favourites. And sort of related, we recently finished reading The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, which went over very well, except that Iris now walks around saying apropos of nothing, “Aslan die?” and I don’t think she knows what die means, or even Aslan for that matter. But Harriet is quite enchanted and now we’re going to read the whole series, and tonight we were reading a new book called Written and Drawn by Henrietta, by TOON Books, and there was a Narnia reference, and I haven’t seen Harriet that excited since she found out she had a wobbly tooth.)

October 1, 2015

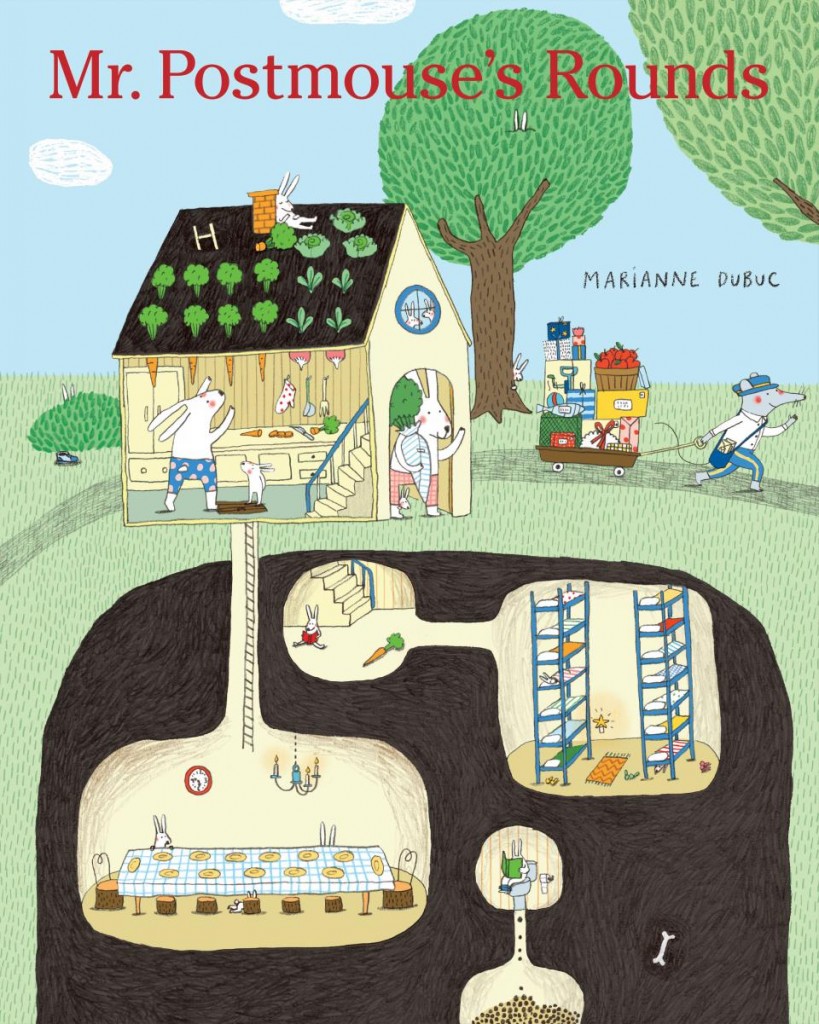

Mr. Postmouse’s Rounds by Marianne Dubuc

We are a little bit crazy for Marianne Dubuc in our house, which is interesting because she does something very different with every book she writes, but what all her books have in common are elements of whimsy, unabashed absurdity, rewards for those who are attentive to detail, and an all-engaging strangeness. And in Mr. Postmouse’s Rounds, she has written a book about the mail, and so naturally I am totally obsessed. As are my kids, because, well, look right there on the cover: there is a rabbit pooing. Sitting on the toilet reading, no less. And this glimpse into the rabbits’ hidden world is what’s so entrancing about this book, exploring these animal abodes that Dubuc has dreamed up: the bear’s house has honey on tap from a hive on the roof; the snake’s long skinny house is outfitted with heat lamps; the squirrel’s got a clothesline and sleeps in a hammock; the mole house has a kettle on the stove.

It’s the kind of book a kid can read with her finger, tracing along the Postmouse’s route and in and out of the houses he delivers to. While the illustration style is very different, we love it for the same reasons I loved Jill Barclay’s Brambly Hedge books when I was little, tiny worlds magnified, access into hidden corners, such incredible attention to detail. And yes, it’s funny. There’s the poo (and the flies’ house is actually a giant piece of much poo, much to everybody’s delight). And there are abandoned shoes, mitts and candy wrappers littering the animals’ neighbourhood, and just what’s going on in each of these dwellings? Each house containing a story of its own, so that you can read Mr. Postmouse’s Rounds over and over again and—which I know from experience—the young reader will continue to keep exploring its pages long after the reading is done.

September 24, 2015

Solid Gold

This week for Picture Book Friday, I bring you the October issue of Quill and Quire, which is on newsstands now. As part of their special Kidlit Spotlight, I took part in a panel discussion focussed around the question, “Are we living in a golden age of Canadian picture books?” It was a very neat, informative and wide-ranging discussion with a bunch of kidlit experts (of which I am now—it’s official). As someone with strong opinions about most books I read, good and bad, it was interesting to hear from others with different points of view. (This is the reason I’m never going to start the blog I was born to write, called “Picture Books I Really Hate”, because these things are so subjective.) It was also really interesting to learn from people whose roots in Canadian children’s books go back to the 1970s (which is basically when Canadian children’s literature began) and find out what is different and what has stayed the same. And is this a golden age? I really do think so. I was pleased that my quotation from Ursula Nordstrom closed our discussion, about books that are written from the outside in, versus books written from the inside out (i.e. the best kind). And there is such a greater level of sophistication in Canadian books at the moment, even by the same writers who were working 30 years ago. Kathy Stinson’s Red is Best is a classic, timeless and fantastic children’s book, but her recent award-winning The Man With the Violin is on a whole other level, which is where so many picture books are appearing these days. It’s a real pleasure to be a part of this literary moment.

Also in the issue are great children’s book reviews, and plenty of other good stuff. Make sure you pick up a copy!

September 22, 2015

The Day the Crayons Came Home

True confession: I don’t love The Day the Crayons Came Home, by Drew Daywelt and Oliver Jeffers, quite as much as I loved its predecessor, The Day the Crayons Quit. The premise is the same but it’s just not as fresh. However my children are quite nuts for the book, and during the first few days after we bought it, Harriet insisted on taking it to bed every night. So when I heard about Small Print TO’s Crayon Creator’s Club event this weekend, I knew we had to be there.

And so on Saturday morning, we headed down to The Lillian Smith Library (which is the most special twenty-year-old building in the universe) and my children posed with the enormous crayons adorning the entrance. We were able to buy a copy of Harold and the Purple Crayon (can you believe we didn’t have it yet) and listened to the story, before the children were let loose to do some purple crayon-ing of their own. (We also learned that Harold actually grew up to be a graffiti artist, ala Bansky.)

After that, we reassembled for The Day the Crayons Came Home, which is about Duncan’s crayons that have been lost, abandoned or broken over the years—left behind on holidays, stuck between couch cushions, puked up by the dog. In the end [SPOILER ALERT] Duncan welcomes his colouring implements home by building them a crayon fort that meets all their special needs now that they’re in altered states. And then each of the children got to work constructing a crayon fort of her or his own.

Next up: the door prize. Guess who was quite thrilled to win a crayon that is taller than she is? (And she doesn’t mind in the slightest that it doesn’t actually colour. If it were made of wax, it would have been even to carry home than it already was.)

All in all, it was a most rewarding morning at one of our favourite places. We posed out by one of the gryphons for posterity.

And speaking of Lillian H. Smith and crayons, I’m quite excited about the All the Libraries colouring book by Daniel Rotsztain, coming next month from Dundurn Press, featuring drawings of every single Toronto Public Library Branch for your colouring pleasure. You can learn more about the project and see some drawings here.

September 17, 2015

Buddy and Earl, by Maureen Fergus and Carey Sookocheff

There are books, and there are books, and even in the realms of the best books, there are the books my children like and the books that I do. And Buddy and Earl, by Maureen Fergus, illustrated by Carey Sookoocheff, manages to be both.

Stories of unlikely pals abound in picture books, and Buddy and Earl is refreshingly different. The characters’ relationship is not built on their respective differences (and learning to appreciate and respect them, blah blah blah) but on highly individuated interactions. Buddy is not just DOG, but A dog with best intentions, insatiable curiosity and a tendency to forgo the rules. Earl is a bad influence with a remarkable imagination and is ever-so-cool that butter wouldn’t melt.

But what is Earl exactly? Answering this question is Buddy’s first task in their relationship, and while Earl attempts to steer him wrong (and have a bit of fun: “I’m a race car!” “I’m a sea urchin.”) before finally revealing his real identity: “The truth is that I’m a talking hair brush.”

Buddy, who’s a bit simple-minded, uses all the rational powers at his disposal to get to the heart of the matter of Earl: “You do not have a steering wheel. You do not have wheels. I do not think that you’re a racecar, Earl.” Or, “You look like a sea urchin, Earl, but I do not think you are a sea urchin. You see, sea urchins are underwear creatures and the living room is not underwater.” Turns out Buddy is not so simple after all. (And reading this deadpan dialogue aloud is so much fun.)

BUT. It turns out the living room IS underwater, or at least it is in the game that Earl ropes Buddy into, a game of pirates, in which the ship is the couch—a dog no-go zone. The two embark upon an eventful voyage with lots of noise and tomfoolery, so that Buddy eventually gets into trouble and Earl gets off scot-free. Because who ever imagined that an innocent hedgehog could cause so much trouble?

In the end, neither is able to identify the other in a taxonomic sense, but both decide it doesn’t matter. Because what are Buddy and Earl after all? Well, they are friends. And this adventure is just the beginning, because there are two more books in store. We are looking forward to them.

September 10, 2015

Daisy Saves the Day, by Shirley Hughes

British institutions collide in today’s Picture Book Friday pick, in which the great Shirley Hughes pens a picture book right out of Downton Abbey with bunting as a major plot point. I know.

British institutions collide in today’s Picture Book Friday pick, in which the great Shirley Hughes pens a picture book right out of Downton Abbey with bunting as a major plot point. I know.

The book is Daisy Saves the Day, about a young girl who has to leave school and take a job as a scullery maid in a grand house in London in order to earn money to help care for her younger siblings. Which was not such a remarkable path for a young girl of her class, but Daisy herself is quite remarkable, bright and clever, hardworking at school. She’s also not particularly good at, well, scullery-ing. Her employers’ modern and unconventional niece, who is visiting from America, wrangles her permission to browse the house’s extensive library however, which makes Daisy’s life a little less lonely.

The story takes place during the summer of 1901 when George V was crowned, and the streets of London were decked in Union Jacks, flags and streamers. (The text doesn’t explicitly say “bunting,” but them there triangles are not just any flags, are they….) Except that Daisy’s house remains plain and unadorned—her employers, The Misses Simms, considered the decorations vulgar. And Daisy, naturally, is disappointed to not be part of the fun.

Ever-enterprising, however, she devises a cheeky way to join in, fashioning a string of bunting out of dishcloths and pillowcases and BRIGHT RED BLOOMERS, no less.

Which, of course, gets her in hot water with the Misses Simms, and poor Daisy is landed in disgrace. She’s given so many extra chores that by the end of the day, she’s too tired to even read. But never fear, there will BE redemption. When one night Cook hangs dishcloths a bit too close to the fire and then nods off, it is Daisy who smells the smoke and rushes to the kitchen to help put the fire out, saving the day, as per the title.

The Misses Simms are so impressed with their young charge that they bestow on her the ultimate gift: they free her from service and offer to pay for her schooling. Because “…it seems to me that you are better at reading than at polishing and scrubbing.” Indeed. And then a happy ending, because Daisy gets to go home to her mother and her brothers. A cheerful end to a cheerful tale, gorgeously rendered in classic Shirley Hughes style, and with endpapers decorated with vintage advertisements for household cleaning products.

We loved this one!

Check out the Daisy Saves the Day website, with more information about the book and activities too.

September 4, 2015

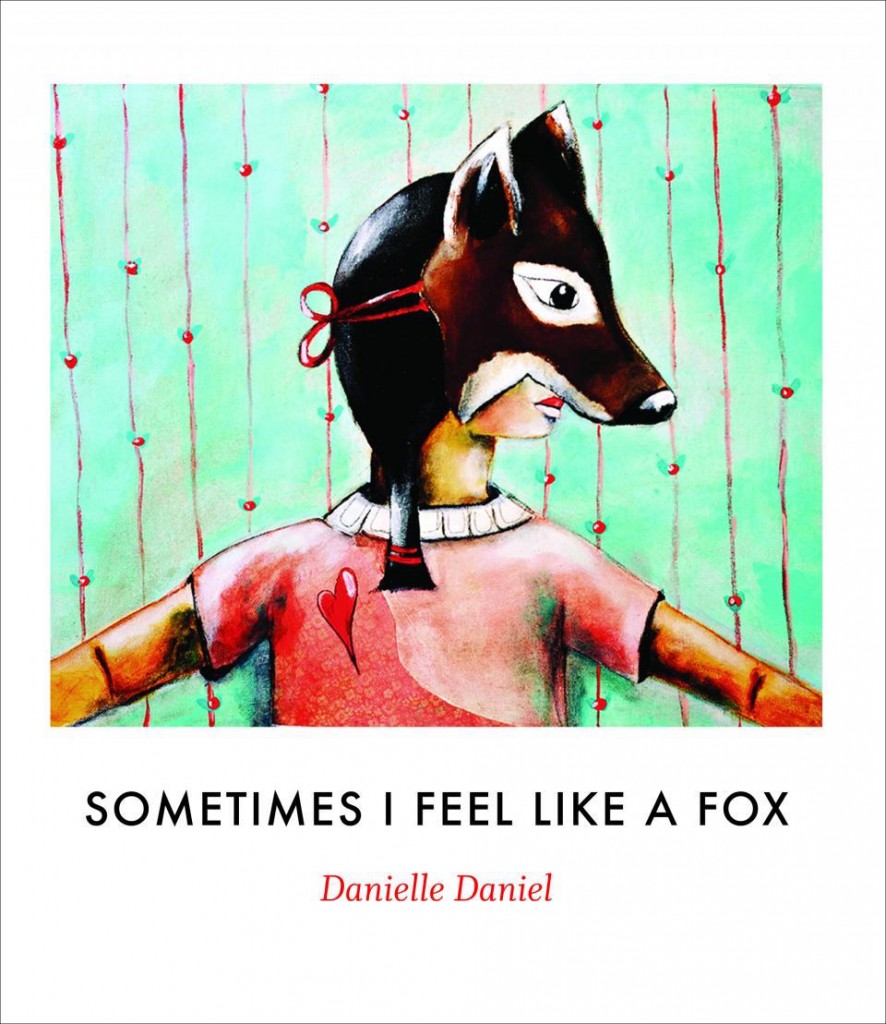

Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, by Danielle Daniel

Today’s Picture Book Friday pick is Sometimes I Feel Like A Fox, by Danielle Daniel, a gorgeous book that my kids love whose meaning is made all the more poignant by its dedication: ““to the thousands of Metis and Aboriginal children who grew up never knowing their totem animal.” Our world is a very complicated place, but I continue to maintain that one very simple thing we can do toward reconciliation with our Metis and First Nations peoples is ensure that our children know their stories, and not just the stereotypes they encounter in so much of classic children’s lit or the “dead Indian” tropes that Thomas King presents in The Inconvenient Indian. And one thing we can do toward healing and ameliorating the status of Indigenous women in Canada is to buy their books, have their stories told. (See the list: Books by Canadian First Nations and Inuit Women.) And so to those ends, picking up a book like this is an important political act.

It’s also a most rewarding literary one.