October 21, 2016

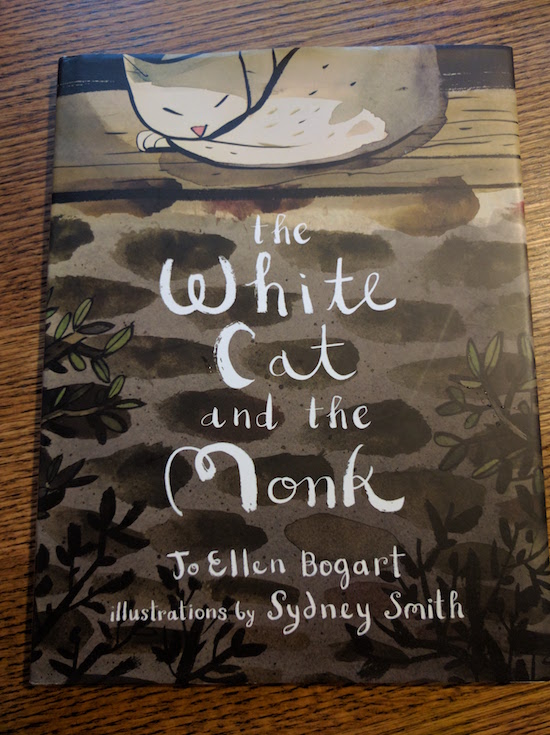

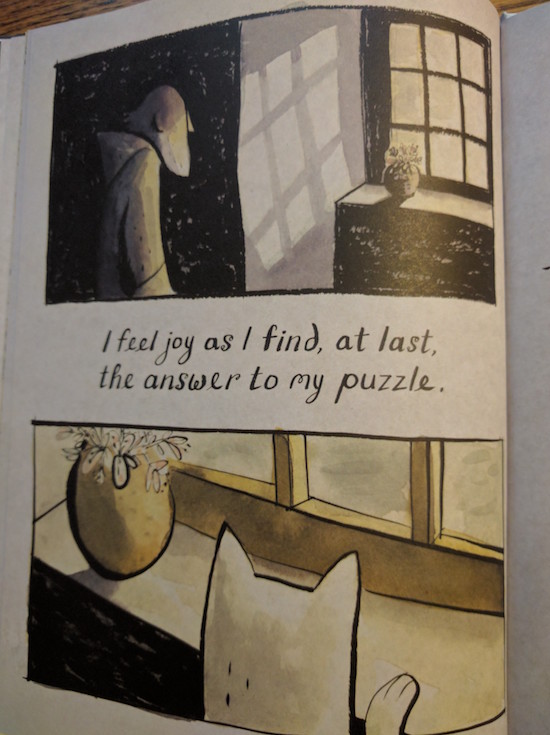

The White Cat and the Monk, by Jo Ellen Bogart and Sydney Smith

Of the many ways in which picture books are superior to all other literary forms is that it’s implicit that the book is going to be read at least one hundred times. You don’t even have to try, it just happens. “Read this one,” says a little voice as little hands force the volume into yours. Again. There are the books on the shelf that get picked up all the time, and even those which aren’t as regularly selected turn up often as a kind of diversion.

The White Cat and the Monk, by Jo Ellen Bogart, illustrated by Sydney Smith, came out in the spring, and we’ve been finding our way deeper and deeper into it with every read. It’s effect is subtle, at first. It’s a simple story based on a poem written more than 1000 years ago by an Irish monk whose name was never recorded. As Jo Ellen Bogart explains in her Author’s Note, the poem, called “Pangur Ban,” has been translated many times throughout the ages, and the words she’s selected for this incarnation are inspired by a number of these.

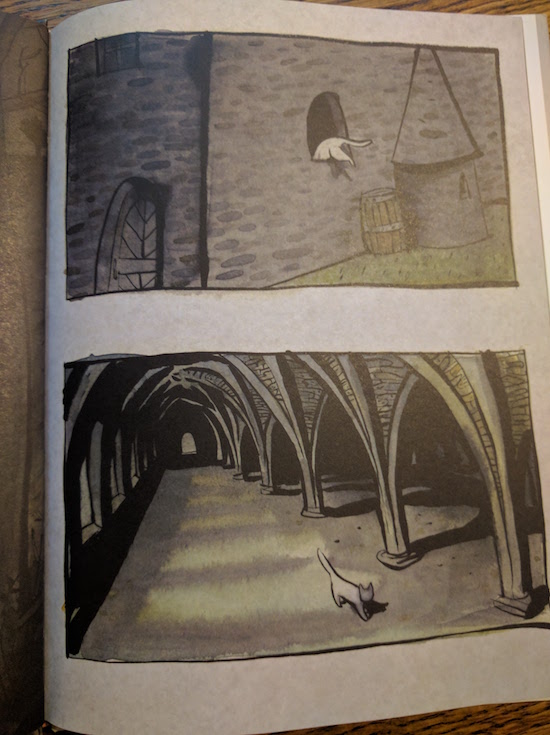

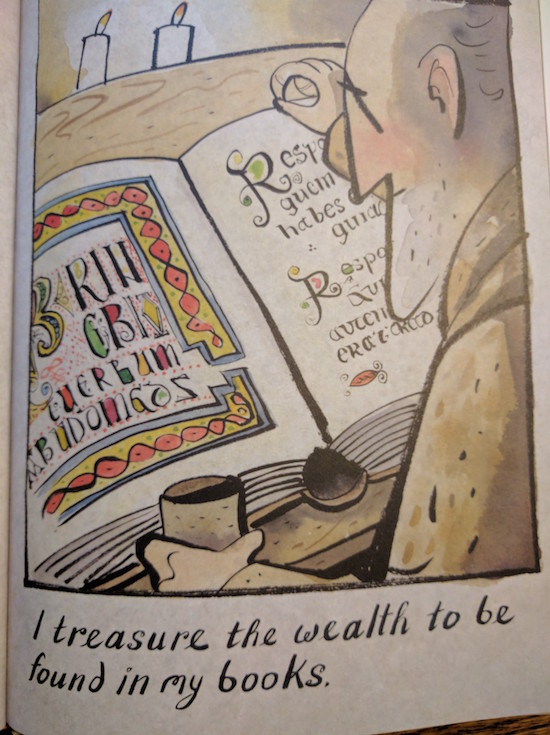

The story is about a monk who spends his days and nights seeking wisdom in the pages of his books, and who identifies with a white cat that has made itself his companion. Quietly, the two together go about their own particular trades, the cat pursuing its mouse and the monk pursuing knowledge.

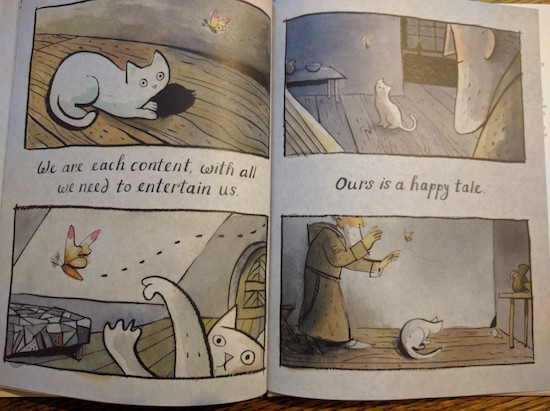

I don’t completely understand the story—that’s why I like reading it so much, getting a better sense of it every time. Is the scholar like a hunter? Is knowledge like prey? And what of the poor mouse? Not such a happy tale for him. It’s a book that raises questions—not surprising for a story based on an anonymous text. And that’s the very point, I think, the reader’s experience analogous with the scholar’s and even the cat’s.

Notions of predator and prey are complicated by an additional layer of meaning offered through Sydney Smith’s gorgeous illustrations with the appearance of a butterfly in the room. The cat swats at it, watching it…and the monk opens the window to set the creature free in the story’s final spread and beautiful last line of text.

And I’m still not sure what the butterfly means, but I trust that in another hundred reads I’ll probably have a good idea.

October 7, 2016

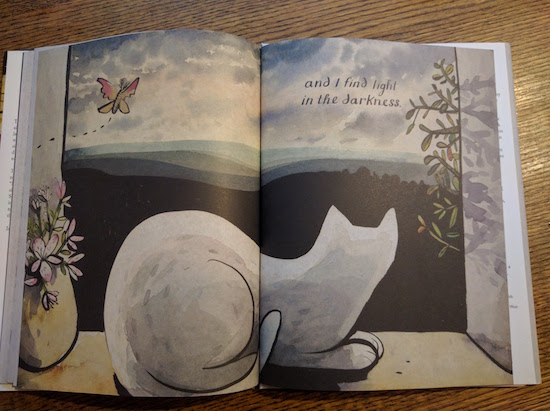

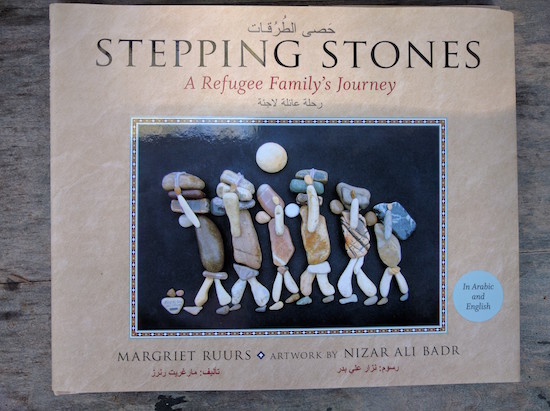

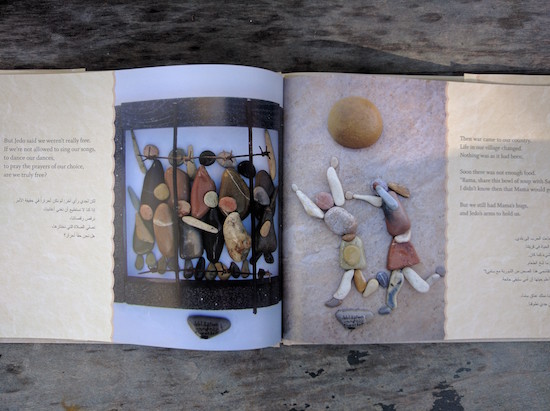

Stepping Stones and The Journey

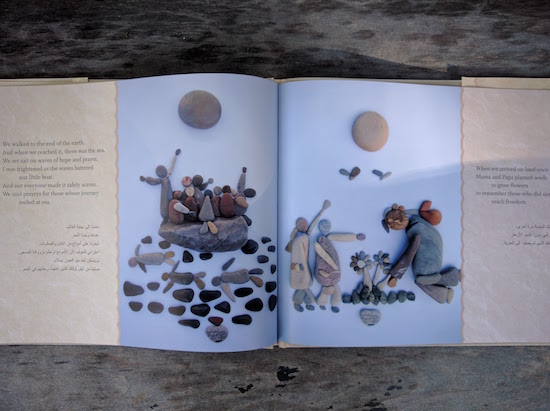

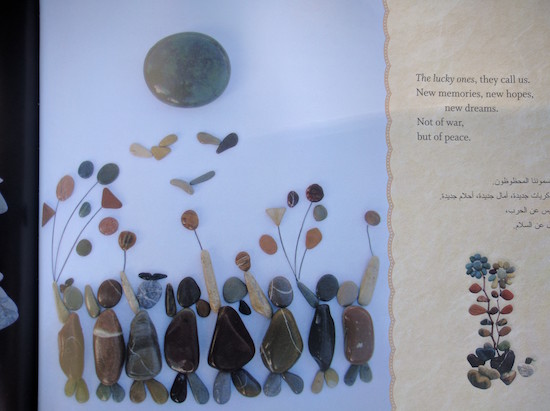

It’s not hyperbole to state that Stepping Stones: A Refugee Family’s Journey, by Margriet Ruurs and Nizam Ali Badhr, is one of the most extraordinary picture books I’ve ever encountered, a book whose incredible origin story is as remarkable as its execution.

The story begins with Syrian artist Nizar Ali Badr, whose evocative scenes created from stones became popular on his Facebook page. Author Ruurs was inspired by the images and eventually managed to contact Badr, and plans were made for them to create a book together. Ruurs secured a contract with Canada’s Orca Books, who were on board with her mission that proceeds from the project be donated to an organization supporting refugees.

Badr’s illustrations are incredible. I never would have imagined that stones could be so creatively arranged to convey action, emotion and narrative. In her introduction to Stepping Stones, Ruurs tells us that Badr, who lives in Latakia, Syria, cannot afford the glue that would render his pictures permanent—and now his images have been collected in a book that people are going read on the other side of the world.

Ruurs’ story is beautifully told, narrated by a young girl whose family is forced to leave the only home she’s ever known, a place of family and friends, memories and familiar scents and sounds. They join, “A river of strangers in search of a place to be free, to live and laugh, to love again. In search of a place where bombs did not fall, where people did not die on their way to market. A river of people in search of peace.” Her text also appears on the page in Arabic, translated by Falah Raheem, making the book accessible to more readers and bring another player into this gorgeous literary transnational collaboration, a book that is very much of this moment and yet timeless at once.

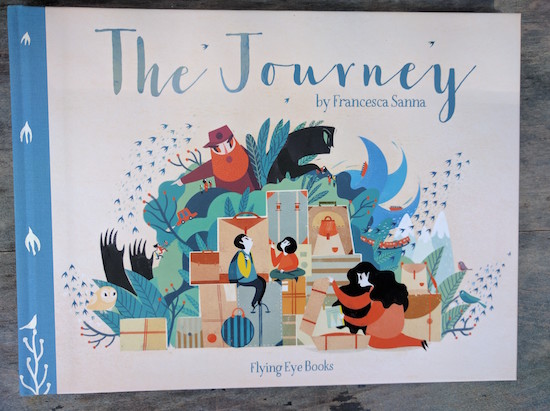

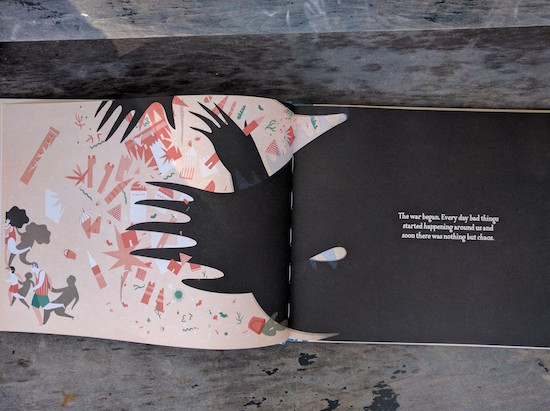

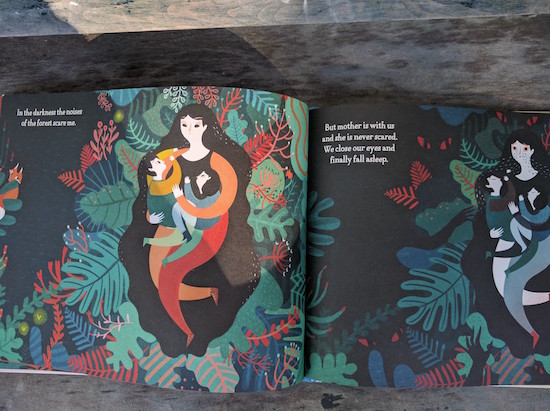

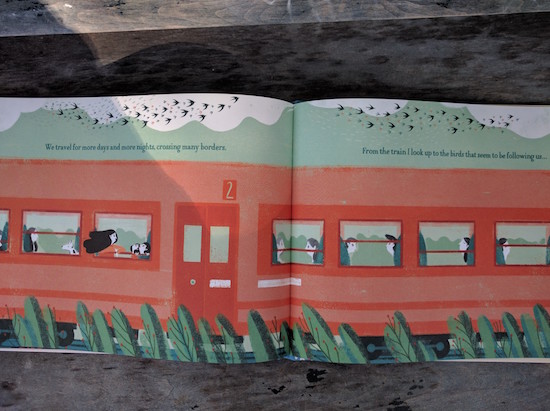

In her book, The Journey, Italian illustrator Francesca Sanna tells a similar story in a different way, a way that in narrative and images recalls fairy tales, Grimms, and an entire canon of stories about people fleeing danger, heroic quests, courage, monsters, danger in the woods, and hope out of the darkness.

Sanna writes that her story is not meant to represent one particular kind of refugee story, but that her book is a collage of different experiences she learned about through her work at a refugee centre in Italy. The stories themselves become a jumping-off point for a narrative that is not necessarily literal, and neither are Sanna’s illustrations, which are dark and compelling (although my daughter as requested that we not read this book at bedtime…)

By car, on foot, by sea, and then by train, the family makes their way, encountering threats along the journey and also help from shady characters. The discerning reader’s heart breaks for the mother.

As with Stepping Stones, The Journey ends on a hopeful note, although the journey isn’t over yet: “I hope one day, like these birds, we will find a new home. A home where we can be safe and begin our story again.”

Reading these books, it occurred to me that it’s not just children who require stories like these in order to better understand current events and the world around us. Politicians, and bigots, and other grownups with hardened hearts who’ve forgotten how to be human—these are the readers who need to read these books in order to remember that people are people, some things are universal, and also that books are amazing.

September 29, 2016

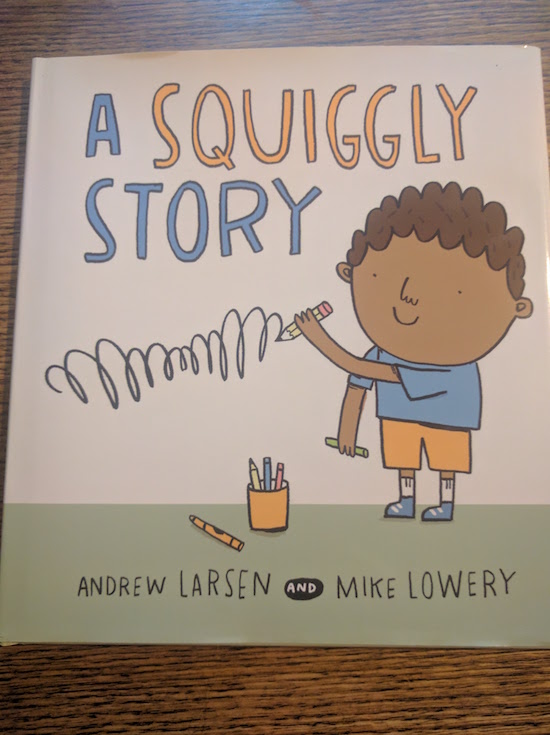

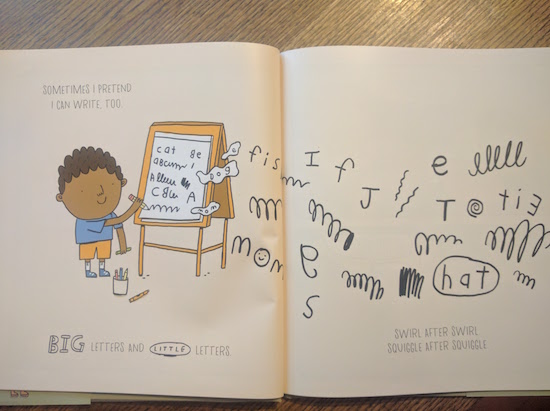

GIVEAWAY! A Squiggly Story, by Andrew Larsen and Mike Lowery

Before my daughter Harriet went to junior kindergarten, she was determined to never be taught anything—by me, at least. I’d read somewhere that a child entering school should be able to write her name, and so that was a benchmark, but Harriet was having none of it. She didn’t even draw pictures. The only thing she ever had to do with paper was taking a pair of scissors and cutting paper into a million tiny pieces, scattering them across our carpet like cheerios.

She did, however, have a notebook, and this was the only bit of “writing” she was willing to be known for, filling page after page with curly lines, the closest she’ll ever get to cursive.

And then she went to school, and it was there the magic happened. Somehow our girl learned to write and to read, and she reads all the time and everywhere, and she writes all the time too (even if her handwriting is atrocious). She makes comics and stories, and she and her friend have written a book at school that they’ve read to kids in the other grade two classes.

And because of Harriet’s example, and because she’s a different person altogether, Iris has a completely different relationship to text and writing than Harriet did at her age. Iris draws amazing pictures, and sits flipping through page after page in novels, and she’s learning her letters—when she sees an “S”, she will shout, “My Daddy has that one,” as if it were some sort of affliction. She knows her classmate’s initials and becomes indignant when a word beginning with A does not actually spell Alma, as it tends to at school.

Most of all though, Iris is partial to her own letter, which is I, and her sister’s H. That the letters fall side-by-side in the alphabet did certainly occur to me when we named Iris, and I also love that an H is an I sideways. They’re often found together in words as well, and Iris is delighted by all of this, finds it intensely meaningful.

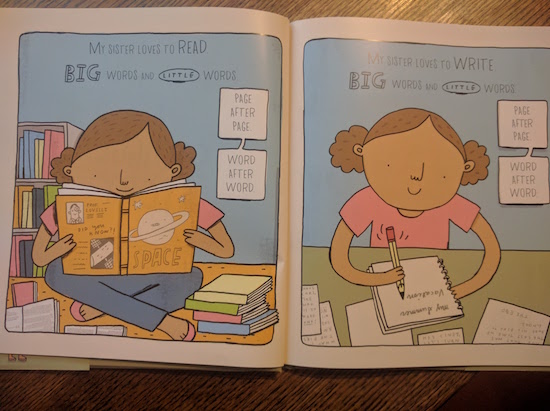

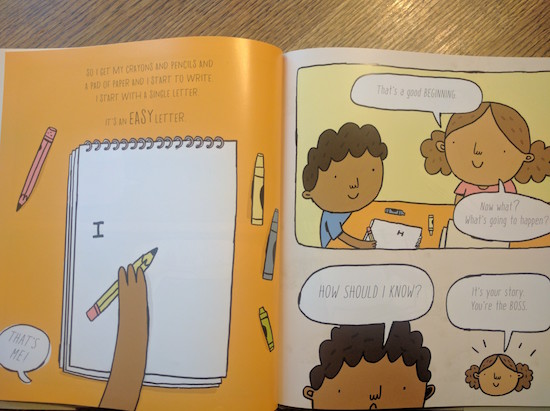

So you can imagine how Iris felt when she saw the above page in Andrew Larsen’s latest picture book, A Squiggly Story, illustrated by Mike Lowery. I is, of course, a letter than is intensely personal to anyone narrating their own experience, but Iris simply took for granted that this was a book that was created just for her.

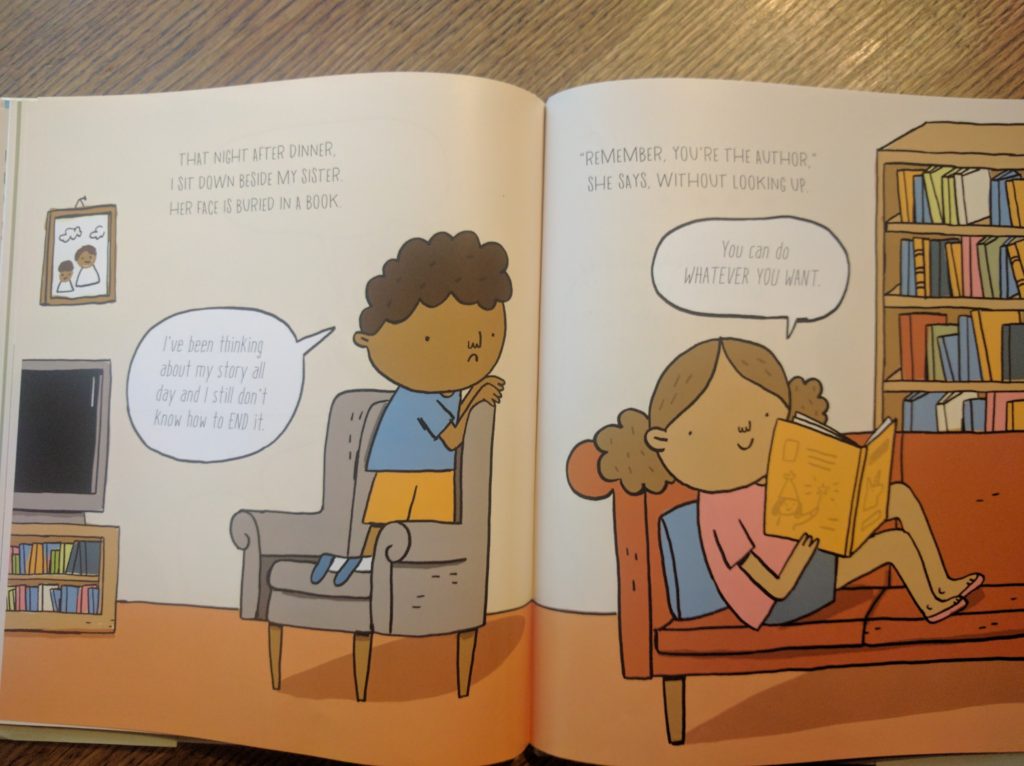

And in a way it was, a book just for her, among many other readers. It’s about a boy who longs to be as deft with words and letters as his older sister, to write a story, and she tells him there’s no reason why he can’t—even if he doesn’t know how to write words yet. “Every story starts with a single word,” she tells him, “and every word starts with a single letter.” This breaking down into smaller pieces concentrated on one step after the other (and another after that) being the best writing advice I know.

So the boy begins his story, a story with I’s and circles and an upside-down V (i.e. a shark fin! This is not a boring story). Empowered by his own creation, the boy takes his story to school and shares it with his classmates, inspiring them to come up with stories of their own and suggestions for his ending. And coming up with one story, of course, makes him think about what kind of story he’s going to imagine next, and the possibilities are endless—a squiggle can be so many different things.

Andrew Larsen is my friend and we’ve had many good discussions about books and writing, and one topic we keep returning to is our distaste with the idea that the outcome of a narrative should necessarily be a protagonist learns a lesson—it’s such a simple minded approach to the role of story in our lives and our experiences. And I love that Andrew’s work reflects this—his are stories that serve to illuminate rather than preach. But a very cool twist is that within his stories I do always find a worthwhile lesson for me, the grown-up reader, to ponder.

“Remember, you’re the author,” the boy’s sister tells him. “You can do whatever you want.”

Fine advice in the writing of a story, but also in the making of a life.

GIVEAWAY: I have an extra copy of A Squiggly Story that you can have a chance to win. Comment on this post and tell me your favourite punctuation mark, and why you love it, and you will be entered in a draw. Canadian residents only. Giveaway closes October 14. October 20.

September 23, 2016

Buddy and Earl and the Great Big Baby

Today for #PictureBookFriday, I’m relinquishing book review duties to Harriet, who has started a blog to explore her fascination with hedgehogs and whose latest post is a review of Buddy and Earl and the Great Big Baby, by Maureen Fergus and Carey Sookocheff, which is the funniest Buddy and Earl book yet (and that is saying something). We love this series, and not just because it features an adorable hedgehogs (although that helps).

September 20, 2016

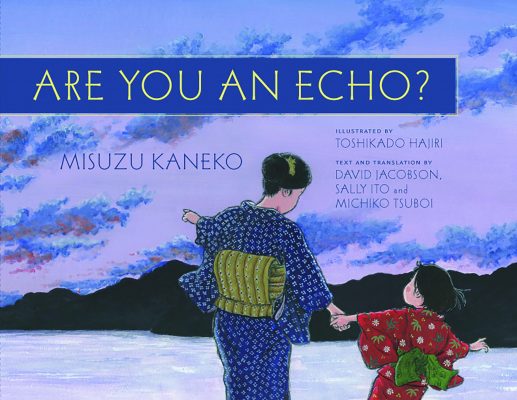

Review: Are You An Echo?

Japan was my home for a while more than a decade ago, and it’s a place I’ll always be grateful to for its generosity, goodness, and what living there taught me about being a person in the world. And so I was especially pleased by the opportunity to review Are You An Echo?, a new book that’s part poetry collection, part biography, and a remarkable collaboration between many different people. It translates Misuzu Kaneko’s poetry into English for the first time, the poems complemented by her difficult life story, and also by the lost-and-found story of these poems themselves, which were “rediscovered” by the Japanese public when the poem “Are You An Echo?” was aired in public service messages on television after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

From my review:

…it seems fitting that Are You an Echo?, a book that brings Kaneko’s work and life story to English readers, is also an exercise in connection. The effort is a unique collaboration between American writer and translator David Jacobson, Canadian translator Sally Ito, Japanese translator Michiko Tsuboi (who studied at the University of Alberta), and Japanese illustrator Toshikado Hajiri. Editor and translators’ notes explain the fascinating creative process involved in this genre-bending mash-up, including on-the-ground research in Japan.

September 15, 2016

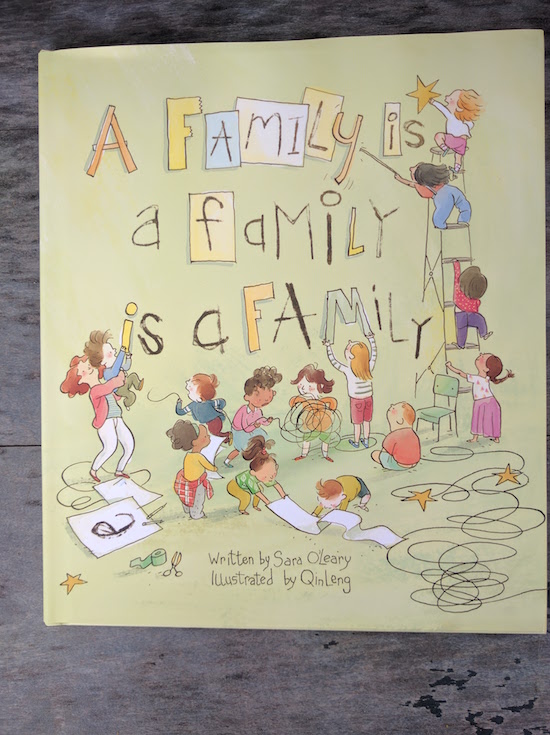

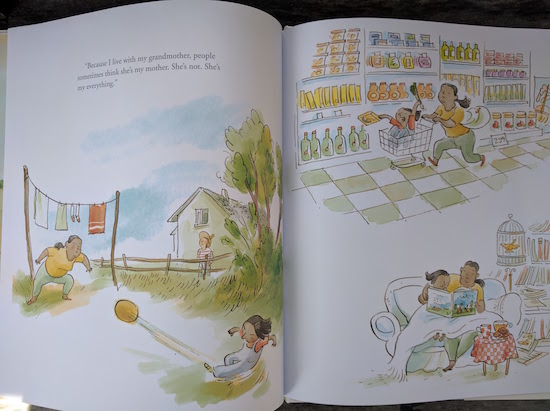

A Family is a Family is a Family, by Sara O’Leary and Qin Leng

There is a special place in my heart for short picture books. And not just because they’re the best books to read on those nights when the day has been long and after-bedtime can’t come soon enough. But also because the best ones manage to be expansive, to incite questions and ideas and discussions, and Sara O’Leary and Qin Leng’s A Family is a Family is a Family is no exception.

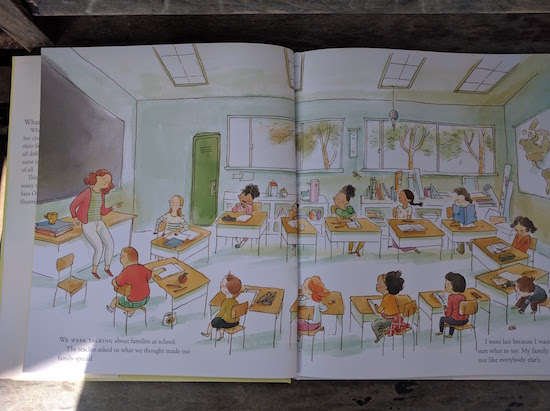

It begins with a classroom discussion, one that could possibly be quite fraught: What makes your family special?

“I went last,” our narrator tells us, “because I wasn’t sure what to say. My family is not like everyone else’s.”

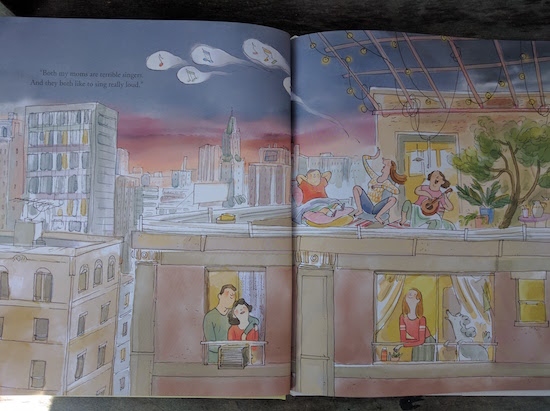

But the revelation of the class discussion is that no one’s family is like every one else’s. And in simple sentences delivered from a child’s eye view we learn what is indeed special about so many different families, the families’ diversity inferred by the reader but diversity not necessarily the speciality, because this is a book about specifics: “Both my moms are terrible singers. And they both like to sing really loud.”

From the child whose parents won’t stop kissing to the family with so many kids, the family with split custody, the blended family, the single parents, two dads, and the child who lives with her grandparents (“Because I live with my grandmother, people sometimes think she is my mother. She’s not. She’s my everything.”)—O’Leary’s story paints a varied and celebratory picture of the many ways there are for a family to be. Leng’s illustrations add richness and texture to the simple prose, with their action-packed and cluttered scenes that suggest a marvellous mess of abundance (which, of course, is love).

In the end, the narrator shares an anecdote in which they’re at the park and a woman asks her foster mother to point out which are her real children.

“Oh, I don’t have any imaginary children,” Mom said. “All my children are real.” (…An idea that took me back to Jo Walton’s My Real Children, which is a novel I loved so much).

This book is terrific for its celebration of family in many forms and of diversity, but also for conversations in general about what a family means and how one is defined. “What makes our family special?” a reader is bound to ask herself after finishing the book, and considering such things—as well as the ways in which we have to nurture our own families as little institutions, a home base in the big wide world—can only do us good.

September 8, 2016

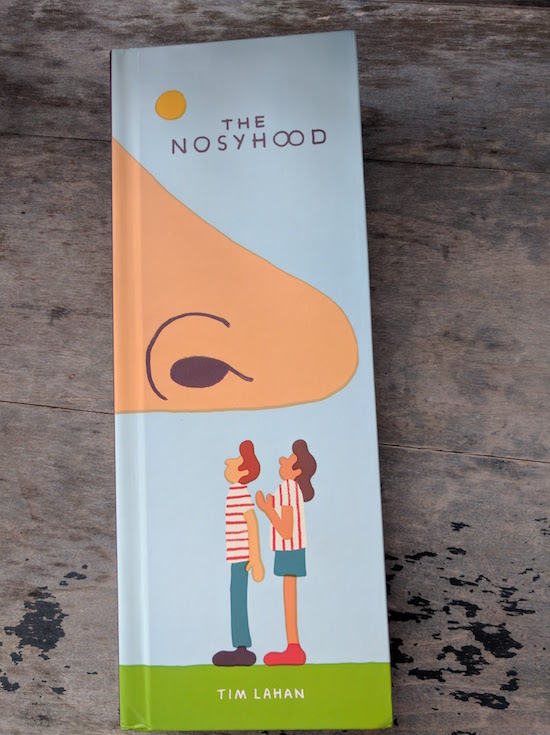

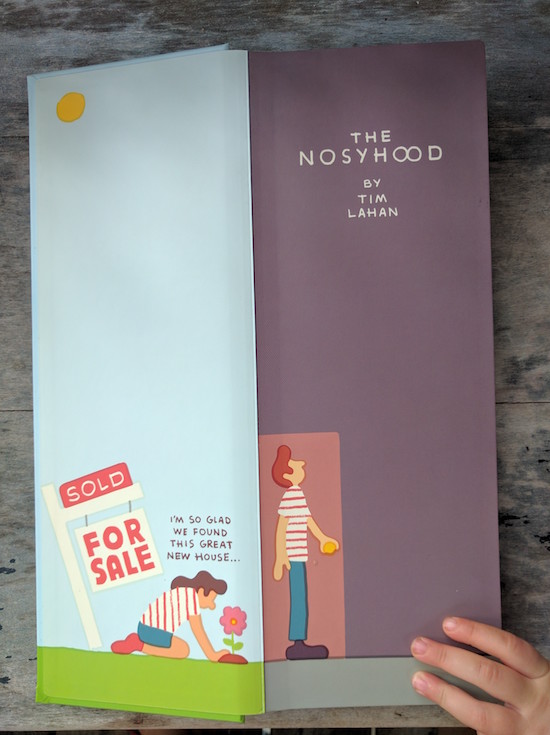

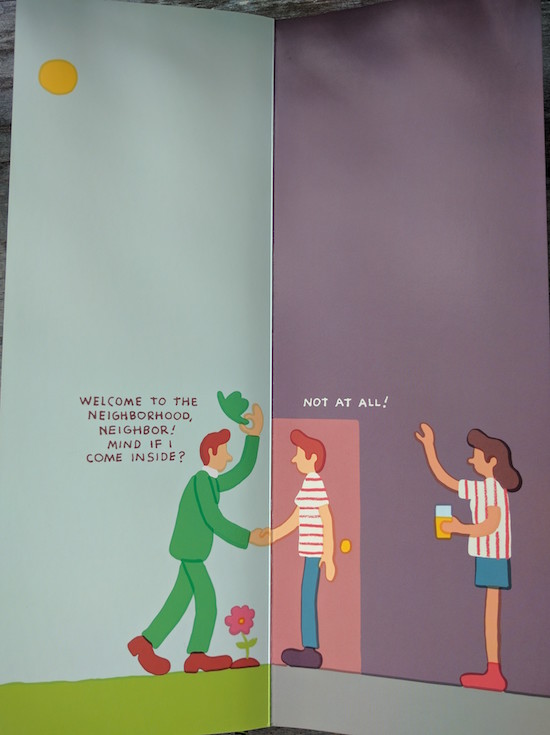

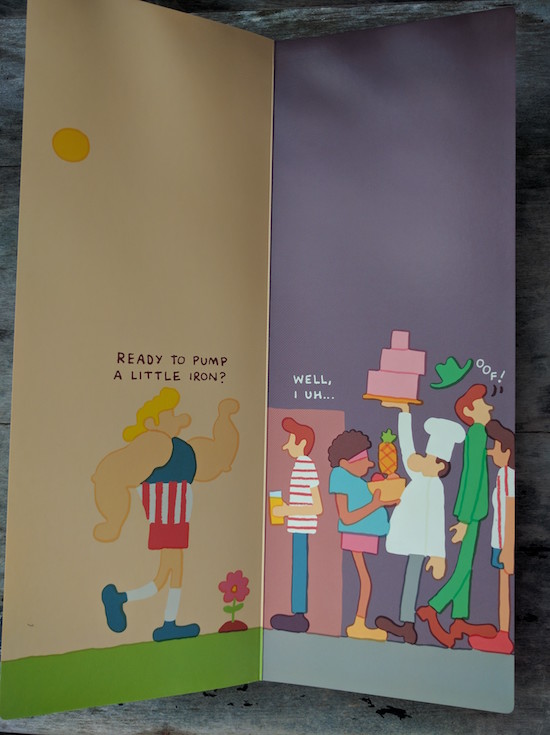

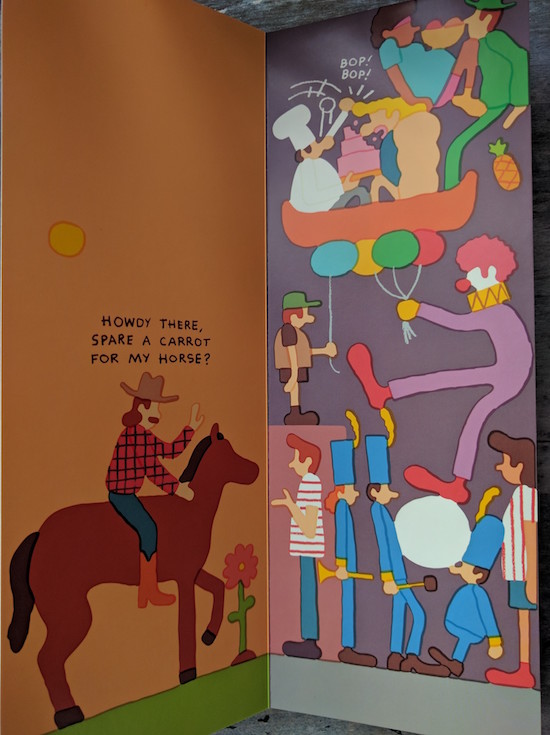

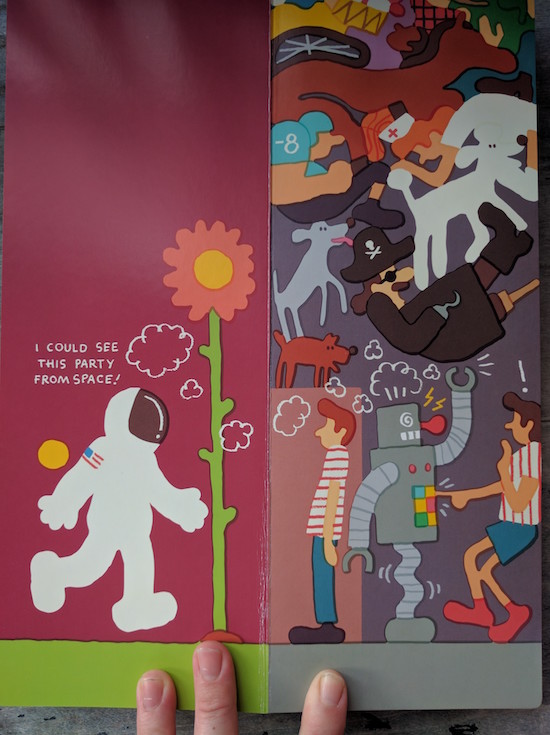

The Nosyhood, by Tim Lahan

Tim Lahan’s first picture book, The Nosyhood, is full of surprises, the first being its size, which is very tall, the book making excellent use of its extraordinary height and being spectacularly conscious of itself as an object (which is very satisfyingly gripped in one’s hands) and the space it has to tell its story.

It’s the story of an unassuming young couple who buy a house, the book’s centre functioning as their home’s threshold. “I’m so glad we found this great new house,” says the Her of the couple, with no idea what their neighbourhood has in store for them.

At first it seems pretty positive—a friendly neighbour (in a green suit) stops by to so hello, and they invite him inside. They’re even cool with the woman who shows with with a bowl full of fruit, and the baker with a three-tiered cake (well, wouldn’t you be?) but when Arnold Schwarzenegger shows up (“Ready to pump a little iron?”) things start to get a little weird. And the party inside is beginning to get a little crowded.

There’s the guy with the canoe, and then the clown with the balloons, and pretty soon this very tall book doesn’t seem tall enough. For the most part, Lahan lets his images tell the story, although they’re nicely punctuated with some dialogue by the party-goers.

The brass band might seems like it’s all gone too far, but there’s still time for the guy on a horse (who’s not just looking for a party, but wants a carrot) and it was here where I realized how wonderfully The Nosyhood reminds me of the works of Remy Charlip, books like Mother Mother I Feel Sick and Arm and Arm and I was definitely thinking about Little Old Big Beard and Big Young Little Beard: A Short and Tall Tale.

It gets absurd. There are donuts by bylaw and the basketball player who turns up saying, “You guys are way more fun than the last seven couples who lived here…” There is the astronaut and the robot and a pirate and three dogs, and you get the sense the something’s gotta give. And when it does, it’s a nose that come around and stopped to sniff the flowers, and when that big nose starts sneezing, everyone would be advised to take cover.  “I feel like this might not be the best neighbourhood for us after all,” the He from the couple is saying to Her at the end as they clean up from the disaster. A perfect, hilarious, understated end to this very funny and clever book.

“I feel like this might not be the best neighbourhood for us after all,” the He from the couple is saying to Her at the end as they clean up from the disaster. A perfect, hilarious, understated end to this very funny and clever book.

September 2, 2016

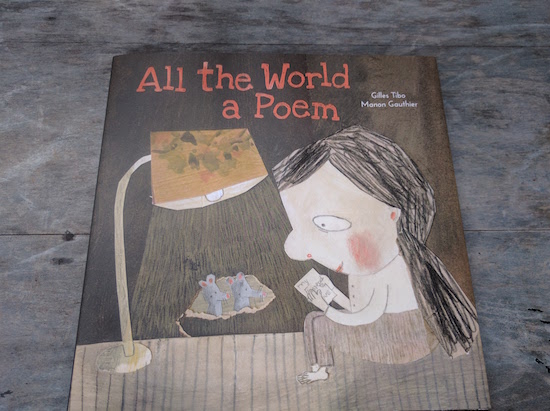

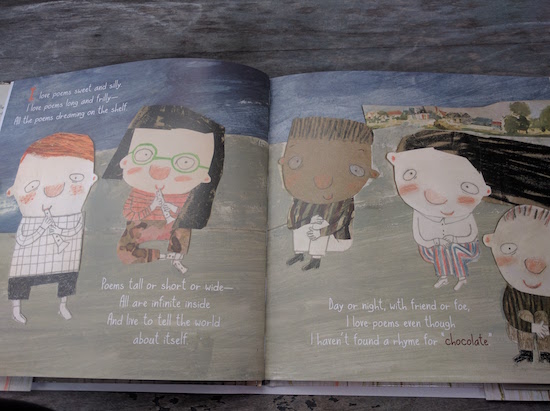

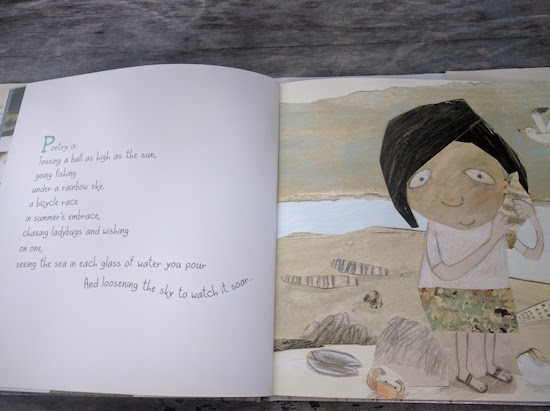

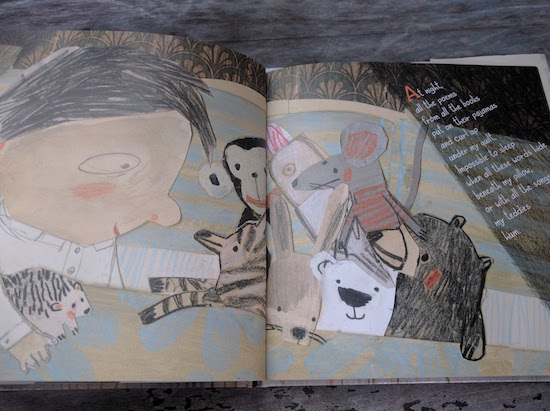

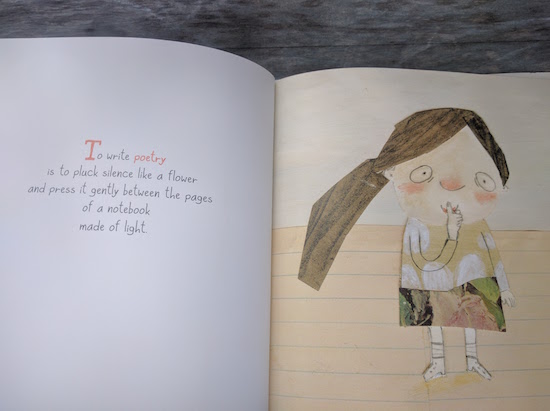

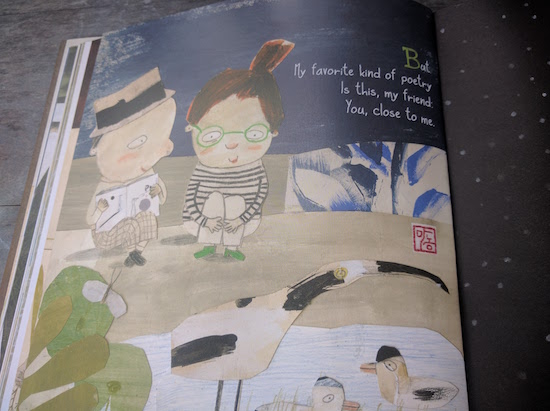

All the World a Poem, by Gilles Tibo and Manon Gauthier

I am totally in love with All the World a Poem, a celebration of the poetry in the world and the world that’s in poetry, written by Gilles Tibo and illustrated by Manon Gauthier, both award-winners in Quebec and internationally. And now their book has been beautifully translated into English by Erin Woods, whose task fascinates me in what it means to translate a poem, poems being is so intrinsically about their language. It’s building the same object out of a different material, and I’m thinking about what changes, what’s retained, and how the translated poems are enriched even, deepened. The translation adds an entire level of meaning to what is already a deeply textured book. Woods delivers full credit for her role in making a book that’s so extraordinary.

Each spread is a different poem celebrating poetry as diverse as the poets who write it, and sometime the poetry is literal (concrete?) and sometimes the poetry is simple (not simple) wonder at the world around one, ephemeral moments and fleeting flyaway things.

Sometimes the poems are loose and free (verse) and other poems rhyme with metre, not all of them obvious and my eldest felt particularly pleased with herself when she thought she’d figured one out.

My favourite page is the one above, silence like a flower pressed between the pages of a notebook made of light. The poems themselves all sophisticated and yet accessible, like the illustrations with their childlike renderings and the richness of texture. Inspiring young readers to see the poetry at work in life and the world, to read it, and maybe even to sit down and write it.

August 25, 2016

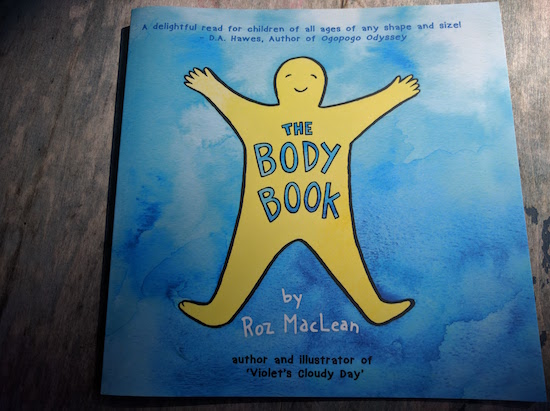

The Body Book, by Roz MacLean

If my copy of Lindy West’s Shrill hadn’t been from the library, among the countless parts I would have underlined would have included the part where she states that she’s never actually hated her body, or felt loathing toward it, but instead was just all too aware that the rest of the world thought that it didn’t conform to its standard. Which has always been my experience, for the most part (which, full disclosure, is also fairly easy for me to say, because my body has rarely deviated very radically from the standard, and let me tell you, there were some years when my body was pretty smoking’ hot [1997 and 2007 in particular were good years; maybe it’s a decennial thing, in which I’m holding out big hopes for the forthcoming annum]).

Truth: I’m still working on losing the baby weight from my second pregnancy—if by “working on losing the baby weight” you mean “eating a lot of croissants and not giving a fuck about the baby weight.”

I’ve always aspired to be quite at home in my body. When I was 17 and wrote for a teen section in our community paper, I plagiarized an article I’d read in a teen magazine about the contentment of a girl who’s eating a McDonalds hot fudge sundae—I wanted to feel that good about myself. That I had to steal the idea though is perfectly telling.

In 2001, I made my friends come with me to the nude beach at Hanlon’s Point when I stripped down to nothing and walked across a beach full of people on my way for a swim, which was truly a life-changing and empowering experience.

In 2012, I took a photograph of myself in a bathing suit and put it on the internet, which I thought was a big deal at the time (and I hadn’t even gained the baby weight!).

Last week I did the same thing again, but by now this didn’t feel remarkable. (What I wrote beside the image did though. “So glad to live in this body,” I captioned the photo, which is, in all honestly, one of the most subversive, badass things a woman can say, and what does that say about us?). And the single biggest thing that I can credit for finally attaining the self-acceptance I’ve been chasing for two decades is this one thing, or two?

I have daughters.

When I became a mother, I made several promises to myself, many of which I eventually broke (including, I will always speak kind and respectfully to my children; I will never bitch at them for reading too much [I know!—but seriously, put the book down, Harriet]; and I will never suddenly exclaim in the middle of an afternoon, “Oh my god, oh my god, all of you, now, just GO AWAY!”). But one promise I have forever stayed true to is that my children will never hear me say a negative word about my appearance. Not one. Because I think that as much as some women may dislike their appearances, all the more omnipresent is the fact that we’re kind of taught that we have to. It’s how to be a woman. Permitting yourself four almonds for a snack, and worrying about “muffin tops” and back fat. So much of it is a learned behaviour, if even by osmosis, and of course it is, because it’s everywhere.

But not in our house. There came a point when I realized our eldest was listening to every word we said and then I stopped whining, “I feel fat” and “I’m ugly!” to my husband whenever I was feeling blah (and let me tell you, other than me, there is no one involved in my personal transformation who has benefitted more than my husband, who apparently doesn’t miss my insecure neediness. Who knew?). I started delivering non-sequiturs at dinner like, “Man, I sure like my freckles,” and “I think my hair looks really pretty today” (about as naturally, at first, as I might bring up topical ideas like online porn or bullying, the kinds of talks you gotta have).

The think about fake it ’til you make it though, is that it’s kind of true. In my experience, there are only so many times you can say, “I sure love how strong my arms are” or “I really like the way I look in this dress” before you start…meaning it. Before you start actually looking for things about you to like and love, because of course it’s good for your daughters, but the thing about it that you never expected is that it’s also good for you.

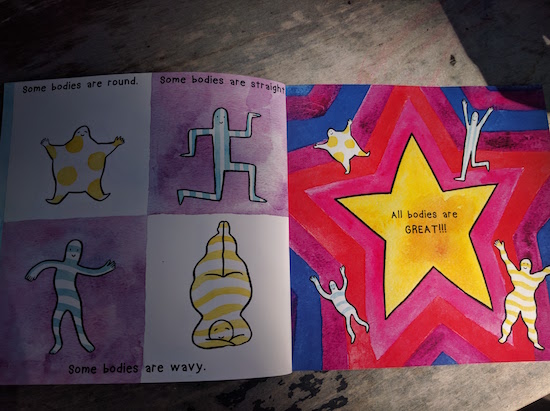

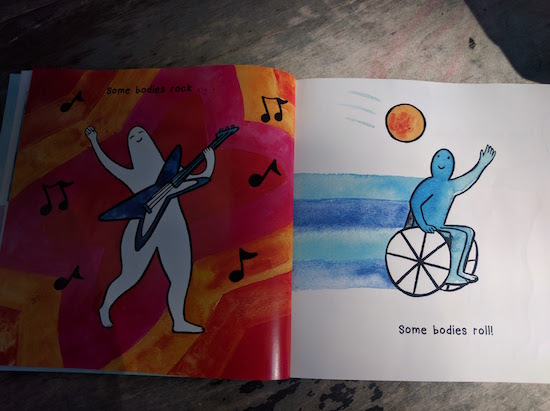

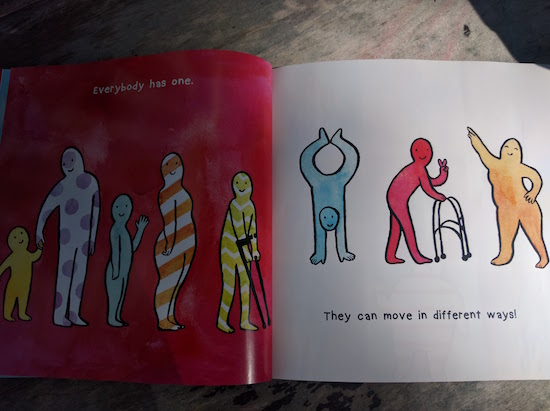

And so this is why I love Roz MacLean’s The Body Book, a simple little paperback with enormous ramifications. Because a mother is going to pick up this book for her child, and they’re both going to enjoy the story’s celebration of bodies of all kinds, shapes, sizes, and abilities: “Some bodies are round./ Some bodies are straight./ Some bodies are wavy./ All bodies are GREAT!!!” She writes about bodies that swim and play, and dance all day, and bodies that love hugs, and bodies that need space, and rocking bodies and rolling bodies, and wibbly bodies, and wobbly bodies too.

All well and good, illustrated with simple cheerful images of blobby bodies in a rainbow of colours all doing what bodies do.

The very best thing about The Body Book though, the most excellent and profound, is that every time that mother reads the book, she’s going to have to deliver the line, “I love my body. Do you love yours too?” A line that, as I’ve stated, is actually one of the bravest, most amazing things that a woman can say.

And I love that once that mother has said it enough, there is a chance she might actually mean it.

July 29, 2016

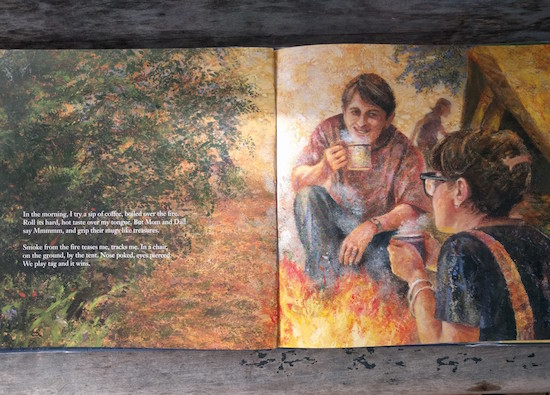

Camping, by Nancy Hundal and Brian Deines

Iris picked this book from a display at Lillian H. Smith Library yesterday, Camping, by Nancy Hundal and Brian Deines, published in 2002. It’s about a family in which nobody is really excited about the prospect of camping, but money is tight and camping is cheap, and throughout the story, they all discover a love of camping. Their experience differs from ours because a) I don’t find camping all that cheap (every year I think we have all the equipment we could possibly need, and then there’s always something more) and b) we are all of us in every family very excited about the prospect of camping. This book has helped us be even more so. (I love the page with the spread of stars the best. The night sky is definitely one of my favourite parts of camping. That, and reading ARC’s of new Louise Penny novels, which seems to be a tradition for me.)

This particular page is the one I love the best though, because indeed there is something about morning campfires and camping coffee and tea. And for sure, we grip our mugs like they’re treasures. Aren’t they though?