October 22, 2024

Ellen and the Lion

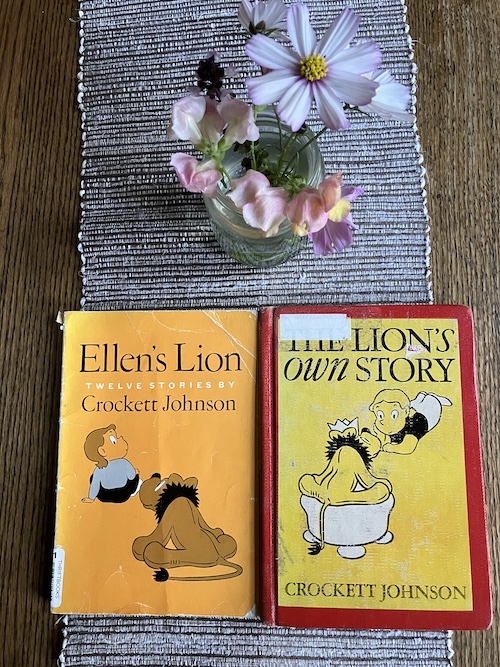

One of the most interesting things about raising kids in our neighbourhood has been our proximity to the Lillian H. Smith Library, home to the Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books (which plays a cameo in my most recent novel!), and whose circulating collection was born out of the Toronto Library’s Boys and Girls House, the first dedicated children’s library in the British commonwealth. When the Lillian H. Smith Library opened on College Street in 1995 (named for the first head of Toronto Public Library’s Children’s Department), the Boys and Girls House collection moved in, which means that on the shelf with books by all the authors you might expect (Shirley Hughes, Jon Klassen, Ruth Ohi, Pat Hutchins, Ezra Jack Keats, Mo Willems) are some obscure vintage gems you might not find at other branches that haven’t been around since 1922, usually trippy 1960s picture books (SPECTACLES, by Ellen Raskin!), and the most legendary of all of these for me (I loved them so much I ended up ordering my own secondhand copies online) has been the two Crockett Johnson books (he of the HAROLD AND THE PURPLE CRAYON fame) about an imaginative girl called Ellen and her stuffed lion, each book a collection of stories, mostly text, and they’re so wonderful, tricky, and funny. Now that my youngest is 11 and we don’t read picture books together so often anymore, we do enjoy these stories and taking turns with the deadpan dialogue.

The bane of my existence, however, is that if you google ELLEN’S LION and the title of Mo Willems’ 2011 book HOORAY FOR AMANDA AND HER ALLIGATOR, the sole search result is the blog post I wrote in 2013 about how Willems was surely inspired by Johnson’s book. And all I want in the world is somebody else to talk about this with, the wit and warmth that these books have in common.

May 22, 2024

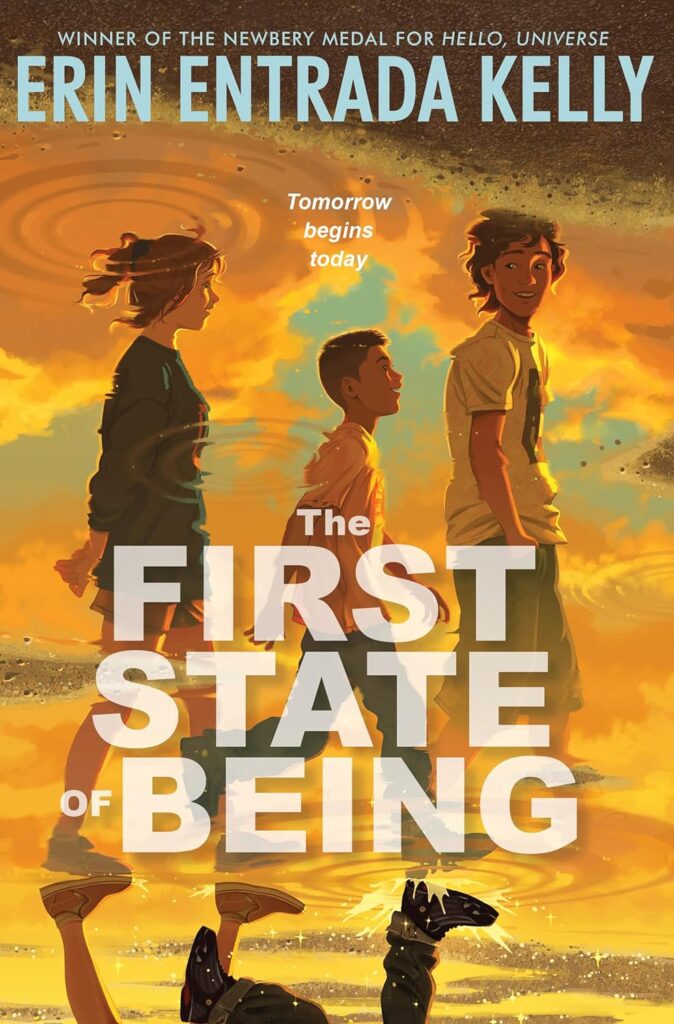

The First State of Being, by Erin Entrada Kelly

“I know it doesn’t seem glamorous or interesting to you right now… But that’s because no one realizes they’re living history every minute of every day. Sure, there are big moments, like the first Black president or the first trip to Mars and Jupiter, or the first STM. But the truth is, we’re making history at this very moment, sitting on this couch together… Every breath we take, we’re contributing to history.”

THE FIRST STATE OF BEING is not actually the first book I’ve read by Erin Entrada Kelly, whose 2017 novel HELLO UNIVERSE was (in addition to winning the Newbery Medal!) a pick for the parent-child book club I was in with my eldest a few years ago. I borrowed her latest novel from the library for her sister, who is (almost) 11, and didn’t have plans to pick it up myself until I leafed through a few pages and started reading the top of Page 43 where it says, “And it’s 1999! The best year!… The Backstreet Boys! Britney Spears! Fight Club! The Matrix! Ricky Martin, livin’ la vida loca! I mean, yes, I was goaded, but the truth is, I WANTED to see it. All of it. Especially the mall. Ordinary, everyday life. Weird?”

And there really was something about 1999, the music, the vibe, and it’s not JUST that it was the year I was 20. If you don’t know what I mean, check out Rob Harvilla’s essay, “How ‘Summer Girls’ Explains a Bunch of Hits—and the Music of 1999.” It was the summer I first learned how it felt to anticipate that incredible key change while belting out “I Want It That Way,” which I’ve been singing ever since, and I honestly never thought at the time that such an ordinary song, an ordinary moment, would prove so eternal, would become another kind of time machine. (The funny thing about growing up in the 1990s in a North America with Francis Fukuyama-inspired headlines and that Jesus Jones track playing in the background is that I really did feel history was everything that had come before us, and that somehow we had managed to be living outside of it.)

THE FIRST STATE OF BEING is set in the summer of 1999 in an apartment complex in Delaware where 12-year-old Michael is hiding stolen canned goods under his bed in preparation for the world falling apart when the calendar flips to the new millennium, Y2K being just one of his many anxieties—his mom is working three jobs and struggling to pay the bills, and Michael feels responsible for the stress she is under. Even worse, she insists on hiring him a babysitter a few days a week, even though Michael is too old for a babysitter, and even worse than that is that Michael has a crush on his babysitter, the brave and brilliant Gibby, age 16, a Neil Diamond cassette jammed in the deck of her 1987 Toyota Corolla.

And then the two of them meet Ridge, a strange-seeming kid hanging out in the courtyard, and when he tells them that he’s a time-travelling visitor from 200 years into the future, his story actually tracks. Ridge is obsessed with 1999, obsessed with seeing a mall, though he refuses to supply the information Michael really wants to know about just how Y2K works out. It turns out that clinging to certainty might not be the answer to anxieties about the future, especially because that leaves no room for the unexpected, and there is all kinds of great wisdom woven throughout the text about doing the best we can with what we’ve got today (which includes looking out for and taking care of each other).

“The first state of being… That’s what my mom calls the present moment. It’s the first state of existence. It’s right now, this moment, in this car. The past is the past. The future is the future. But this, right now? This is the first state, the most important one, the one in which everything matters.”

I LOVED THIS BOOK. And then I made my husband read it, and he loved it too. We’ve both adored Connie Willis’s Oxford Time Travel series, and this novel gestures toward their ethos in a subtle way, and I was also pleased to find an obligatory reference to Back to the Future and concerns about the Space-Time-Continuum, of course. Though THE FIRST STATE OF BEING’s treatment of time travel was also pretty fresh in its own right, transcripts from Ridge’s time and excerpts from contemporaneous books and articles about time travel and the technology behind it interspersing the 1999 chapters, these additions enhancing the novel and leading to more than a few moments when everything *clicked* and I started shouting with excitement as the pieces came together.

Too many science fiction books (especially for grown-ups!) become unwieldy, narratives overburdened by world-building, which makes the brevity and light touch of THE FIRST STATE OF BEING—a story built on all things huge and existential—all the more remarkable. How Erin Entrada Kelly managed to fit so much so easily into a story so brief must have been an exercise in essentiality, but she struck the balance exactly right, and I really can’t stop thinking about all it.

April 24, 2024

Understanding Carries the Light

“Wisdom is valuable. But the ability to find understanding is a gift that all creation enjoys… In some ways, you can think of wisdom of light. But it is understanding that carries the light. Understanding is what wisdom travels through.” —from The Case of the Rigged Race, by Michael Hutchinson

I really love the Ontario Library Association’s Forest of Reading Program, mainly because it’s like our family’s version of sports. (Librarians put together different reading lists for all ages, and school children vote for their faves, culminating in an absolutely bonkers in-person festival every May.) My kids’ schools do a good job running the program, but I borrow the books from the public library too just to provide more of a chance to get through the lists. And not all the books end up working for my children, which is fine, because I want to empower them as readers to follow their own instincts and make their own choices. But when Iris couldn’t get into The Case of the Rigged Race: A Mighty Muskrats Mystery, by Michael Hutchinson, a member of the Misipawistik Cree Nation, I didn’t want to just let it go. Even though I understood that it was not her kind of book—about mostly boys, a dog-sled race, the cover lacks an image of a tween girl sipping boba—but I was thinking about Elaine Castillo’s essay collection How to Read Now and how to be white is so often to assume oneself to be “the expected reader” of a story, no adaptations or great leaps necessary. And I wanted Iris to make the leap of reading a book for which she was not necessarily THE expected reader—Hutchison’s series are set on a Northern reserve and are a rare example of middle grade fiction in which an Indigenous kid would see themself represented. But sometimes (almost all the time) in parenting, if you want to make things happen you have to put your money where your mouth is. So Iris and I sat down and read it out loud together.

And am I ever glad we did. I was not expecting the experience to be so rich, the book itself to be so meaningful. A story about a gang of pre-teen cousins solving crimes sounds like a lot of stories I’ve read before, formulaic and flimsy-of-plot, but Hutchison’s novel (Book Four in a series) is the real deal, which is the kind of thing you know for sure once you’ve read an entire book out loud. Complex vocabulary, lots of fun wordplay, moral conundrums, flawed adult characters whose struggles are shown with real empathy, a portrayal of the realities of northern rez life (the prices at the grocery store!), carefully drawn protagonists, and a mystery that was interesting to unravel—I didn’t see any of that coming. But I especially didn’t expect the kids’ grandfather’s lesson—quoted above—to resonate so strongly with me, and to illuminate so many of the problems that occupy my mind half the time.

Wisdom is light (and so is righteousness), “but it is understanding that carries the light.”

What a gorgeous and absolutely necessary message. I’m so glad I got to receive it. Nice pick, OLA!

November 25, 2020

The Seasons of My Life

I have outgrown picture books…again.

Which I feel nervous even writing. If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all, and all that jazz, and I have learned through my interest in kids’ books over the last eleven years that those who create these books can be a bit sensitive about their work, about its relegation to the world of childish things. Wonderful children’s literature appeals to readers of all ages, and readers who restrict themselves to a certain age group (or genre, etc.) are missing out. All of this is true.

But it’s nothing not-nice that I’m trying to say here. Instead, it’s a matter of practicality. That for a long time, picture books were my primary way of engaging with my children and this opened up whole worlds to me, and some of those worlds seemed as real as the one I walk around in every day—but time makes you bolder and children get older, and I’m getting older too?

We still read them sometimes. Iris is only seven and we have so many great books on our shelves that all of us enjoy, books we can recite by heart. There are picture books in our library I’ll never be able to part with, and yet—we’re reading them less and less. I used to blog about picture books weekly, but now I hardly do. Everybody in our family is firmly into chapter books now, books we read on our own and the ones we read together. Picture books don’t have the same integral place in our daily life that they once did.

And none of this is remarkable. Children outgrow a lot of things, and families do too. We used to go on road trips listening to the same CD on repeat, this song with a barking dog in the chorus, because Iris cried in the car otherwise, and we don’t do that anymore. I used to get a big kick out of reading Go Dog Go in ridiculous accents, but these days the dog party is over.

But I feel a little bit disloyal, admitting to giving up on my allegiance to picture books. Or rather, moving on from it—although the new frontier, for me, is middle grade and also graphic novels, and I’m getting the same pleasure from relating to Harriet through some of the novels she’s reading as I once did when we used to examine the illustrations in Allan and Janet Ahlberg’s Peepo together, her gummy baby fingers pointing out the dog in the corner that shouldn’t be there. But I’m also trying to give her space to develop her own relationship with books and reading, one that has nothing to do with me.

And this is what happens, of course, the way things come and go. And how when they go, new things grow up in their place, which I keep reminding myself of in these moments of unprecedented change and upheaval. As businesses shut down in my neighbourhood and city and it’s enough to drive one to despair sometimes, the extent of the loss, all of it so overwhelming and hard. But even harder is trying to hold on to it all.

(And remember: a blog needs space to grow and room to wander!)

It’s okay to grow. It’s okay to change. It’s okay to change again, is what I’m thinking, and for the thing that used to define you so much and mean everything to become a spot of the horizon. And those things we loved will always be a part of who we are, because of the way that we wouldn’t have become ourselves without them.

October 18, 2020

How I Made My Children Readers: My ONE Magic Secret

Okay, as everybody knows, my children are readers because LUCK and because they happened to be born with those inclinations, and because they are fortunate that reading comes easily for their brains. LUCK also that neither of them decided to hate reading out of spite, because their mom was just way too into it. (I was anticipating this. Have done my best—and no doubt failed—not to be too much about the whole reading thing, and give them space to develop their own tastes and connection to reading that was not just an extension of mine.) This is probably 75% of the formula.

In addition, books and reading are an essential part of our family culture, they see me and their dad reading all the time, I’ve surrounded them with excellent books since before they were born, and it’s rare that they’ve ever taken a journey that didn’t end at a bookshop (and then ice cream).

But my magic secret to raising readers is none of these. My magic secret is much less wholesome, is sexist and outdated, and is available in digest form at your local grocery store. My magic secret to raising readers is ARCHIE COMICS.

And here’s why.

1 ) I buy them at the grocery store checkout, along with milk and cheese and breakfast cereal, underlining the point that reading materials can be staples, sundries just as essential as toilet paper and dish soap. They’re always appreciated, and special enough to turn up in Christmas stockings, but they’re kind of viewed there the way that socks in the stockings are. Nice to have, but ubiquitous.

2) Ubiquitous, which is to say accessible. They’re cheap. Can be taken for granted. Unremarkable. They’re just always around.

3) Being so accessible, they’re also disposable. They’re the books my children bring to the table at lunchtime because nobody cares if they get splattered with soup. Nobody has to be precious with a book like this.

4) These are also stories that ask little of their readers. They don’t require a lot of attention or brain power. They’re perfect for if you’re really tired. My daughter likes to read one as a palette cleanser after reading something intense or demanding before bed. They’re not edifying. In short, they are basically literary candy. Unlimited literary candy. And unlimited candy is basically every kid’s dream. (Just don’t tell them that they’re building literacy as a lifelong habit!)

5) I bought two comics last week when we were waiting in the drug store for our flu shots. Archie comics pass the time, and because they’re broken up into pieces, you can read them at three minute intervals or for ages and ages. Picking them up and putting them down is easy , and so they’re really easy to integrate into the course of one’s day. SEVERAL TIMES.

And because they’re so ubiquitous, there’s usually a small pile of them within arm’s reach anyway. Nobody has to go out of their way, which is just the way literacy training ought to be.

February 28, 2020

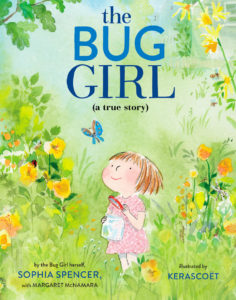

The Bug Girl, by Sophia Spencer

The Bug Girl, by Sophia Spencer, with Margaret McNamara, has a very cool backstory—when a young girl with a passion for insects finds herself bullied by peers, her mother reached out to professional entomologists to offer support for the girl, which went viral. And this is how Sophia Spencer became a debut picture book author at the age of 9, but even knowing none of this, there is a lot to love about The Bug Girl. It’s a book about unabashedly being yourself, about pursuing your own avenues and fascinations, and about defying other people who might hold those fascinations against you. The book is sweet and fun, but also an inspiring call to resist peer pressure, and to understand just how great and wondrous the world is—beyond the limits of one’s own community, and also right down to the smallest creatures on earth.

February 4, 2020

Discovering Emily

“Everybody loves Anne, but I like Emily. She’s dark.” —Russian Doll

It was a year ago now that I was swept along in the enthusiasm for the Netflix series Russian Doll, starring Natasha Lyonne, a strange and enigmatic show in which the novel Emily of New Moon featured as a major plot point. Which was just as weird and curious as everything about the show, and it put Emily on my radar for the first time in years. Emily, a second-tier Anne of Green Gables, I’d always supposed, the case not helped by the cover of the Seal paperback that featured prominently in my childhood, which is basically just Anne with different coloured braids.

This specific copy is stolen from the library of the school where I attended Grade 7 and 8. I am not sure exactly if I was the thief, but somehow this ended up in a box in my mom’s basement and I brought it home not long ago, because of Russian Doll.

In childhood, Emily was wasted on me. I know that I read the whole series because I’m now just one chapter away from rereading Emily of New Moon (have been reading it aloud to my family for the past couple of months) and remember parts of the story from when Emily is a bit older, which is mainly her totally gross relationship with the much-older Dean Priest. I know I read the whole series, because I was an L.M. Montgomery completist, but it mostly just left me with questions. Like what was up with Dean Priest? (Upon reread, I still don’t know the answer to this.) Where exactly was Stovepipe Town? And “the flash.” I didn’t understand “the flash.” Emily of New Moon was Anne of Green Gables, but weirder. Emily is dark—Russian Doll was right. And as a young reader, I didn’t have the understanding to appreciate that, or to appreciate the novel properly at all.

But it’s so good. The takeaway from our family read is this. The number of times I’ve come to the end of a paragraph and stopped reading, and everybody starts yelling at me, “No, no. Come on! Keep going! What happens next?” The story itself a bit overwrought and melodramatic, but not to the detriment of the reader’s enjoyment. And not without a sense of humour either—when Emily eats the poisoned apple! The ghost in the walls at Nancy Priest’s house! A cast of characters so firmly realized that when the narrative notes that Perry Miler would be the leader of Canada one day, my children asked me if this had actually transpired. And I don’t want to knock Anne, but Emily’s friends are so much more interesting that Diana. Foul-mouthed Ilse Burnley (and the mystery of her runaway mother), and Perry (who in one scene hangs naked from the kitchen ceiling), and Teddy Kent with his suffocating mother who drowns his cats because she can’t bear that he loves anything but her.

Emily is a fantastic character, up there with Harriet M. Welch as a person whose boldness and will I’d like to channel. Where Anne Shirley was desperate for love and to be liked, Emily has spent most of her childhood in the care of a doting father who gave her a remarkable inheritance, an indelible sense of herself. She knows her worth and her value, and when others don’t, she sees it more as a reflection on them than on her. Even when she arrives at New Moon, where she is an outsider (her mother years ago had run away from her family there to marry her father), she is able to draw on the traditions of her mother’s family and their heritage to further shape her own identity. She knows who she is, and where she came from, which gives her an impressively strong foundation to build her self upon.

Her steadfastness is so admirable, and curious in a child. There is an uncannyness to her character that makes even the most sensible grown-ups uncomfortable, and this tension makes for fascinating reading. And so does the action—Montgomery channels the same gothic darkness here that made her The Blue Castle so delicious, but the novel is also filled with light and the pleasures of everyday. I love the chatty and mundane letters Emily has written to her late father, which reminded me of my favourite parts of another Montgomery novel I loved, The Road to Yesterday (in fact The Golden Road! The LM Montgomery Society kindly corrected me on Twitter) in which a group of cousins put together a newspaper. And I think Aunt Elizabeth might be my favourite Montgomery character since Marilla Cuthbert.

December 6, 2019

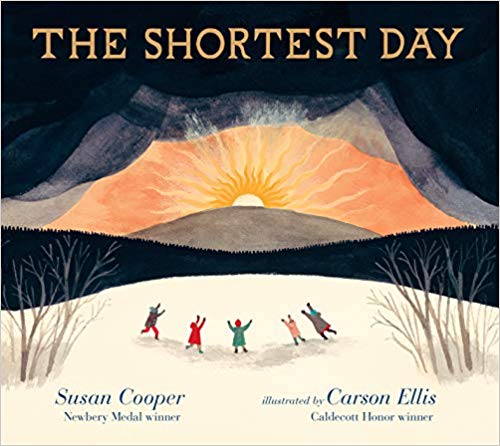

The Shortest Day, by Susan Cooper and Carson Ellis

“So the shortest day came, and the year died…” begins The Shortest Day, an extraordinary picture book by Susan Cooper, with illustrations by Carson Ellis, a celebration of solstice, Yuletide, and rituals that light up the darkness. “And everywhere down the centuries/ of the snow-white world/ Came people singing, dancing,/ To drive the dark away.” In her illustrations, Ellis shows those centuries progressing in Northern European cultures, as people move from the Neolithic era, carrying spears, and then “down the centuries” to the contemporary moment, children revelling in a warm and cozy home decorated with an evergreen tree and boughs, candles and a menorah, traditions that connect us to our ancestors and to the earth. This is one of the loveliest “Christmas” books that I’ve ever come across, a book that celebrates what, to me, are the most sacred parts of the season.

October 25, 2019

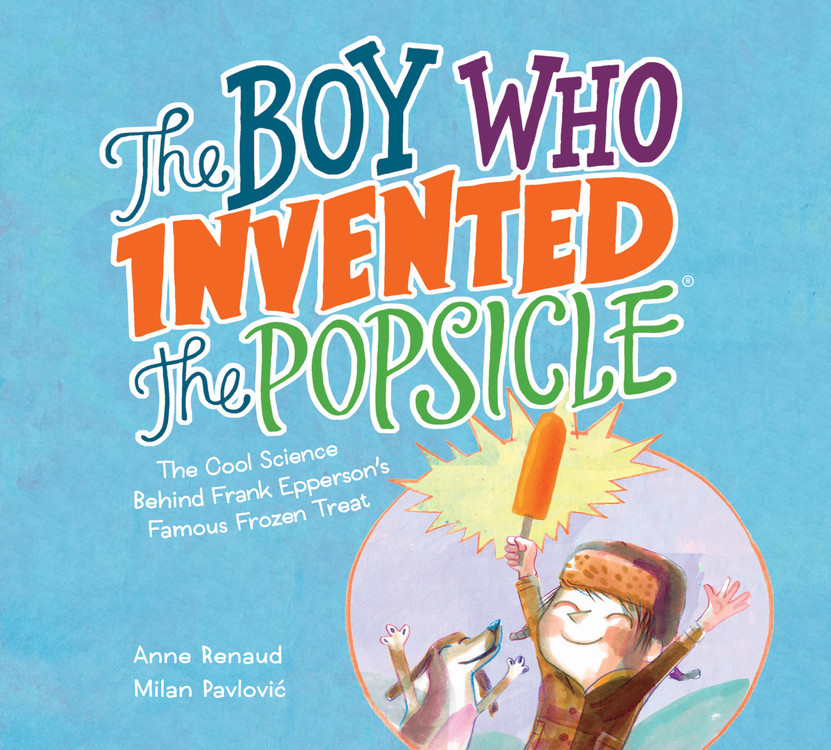

The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle, by Anne Renaud and Milan Pavlovic

For some reason, unless they happen to encyclopedic catalogues fun to flip through but with no overarching narrative, non-fiction gets short shrift with the young readers in my house. We’ve got a whole stack of titles about history and animals, dinosaurs, guides to crafting and science experiments, none of them appreciated as well as they should be, and my children read Archie comics to tatters instead.

But The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle, by Anne Renaud and Milan Pavlovic, is the exception to that rule, primarily because it’s a fabulous hybrid of a book—a great story that’s fun to read aloud; a biography based on Frank Epperson who really did invent the Popsicle; a gorgeous book with great design (endpapers to die for!); and it’s got science experiments—on mixing oil and water, how to make fizzy drinks, how to lower the freezing point of water—each one connected to the narrative, which is not only engaging, but also demonstrates the experiments’ real-world implications.

One of my favourite picture book biographies ever is Monica Kulling’s Spic-and-Span!: Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen, and The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle is kind of a companion, a story that blends the scientific and domestic realms, that shows how having children can inspire an inventor’s ideas, a story that makes the familiar extraordinary by taking an every day item (the popsicle!) back to its origins. It also shows how childhood dreams can transform into reality, and how curiosity and an insistence on asking questions can serve a person throughout his life.

October 10, 2019

The Girl Who Rode a Shark, by Ailsa Ross and Amy Blackwell

I’m not yet bored of stories of brave and uncommon women, and this is not even a genre that began with Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls. Virginia Woolf published several biographical essay throughout her career—it was from “Lives of the Obscure,” in The Common Reader, that I learned about the Victoria entomologist Eleanor Ormerod, for example, and without Woolf we wouldn’t even know about Shakespeare’s Sister at all. Truth be told, I actually found Good Night Stories... a bit wanting…but that’s because I’d read Rad Women Worldwide before it, and liked it so much better.

But another similar book, The Girl Who Rode a Shark, by Ailsa Ross (who lives in Alberta!) and Amy Blackwell, has managed to live up to my expectations. My favourite bit is the Canadian content—we’re almost at the Roberta Bondar essay. And Indigenous hero Shannon Koostachin is included in “The Activists” chapter.

The women profiled in the book come from places all over the world, include many women of colour, and also women with disabilities. Even better—while many of the profiles are of historical figures, just as many are contemporary, young women who are out there doing brave and groundbreaking things as we’re reading. A few of these figures are familiar, but more are new to us, and their stories are made vivid and compelling through the book’s beautiful artwork and smart and engaging prose.