October 12, 2022

“Learning and Growing Through Our Entire Lives”: A Conversation with Ann Douglas

In 2013, when the anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood was published, I was so thrilled to receive a blurb from parenting writer Ann Douglas, and so it felt like things had come full circle when I was able to provide an endorsement for her latest book, Navigating the Messy Middle, a book that marks a shift in Douglas’s own professional journey. “The best thing about Ann Douglas’s perspective, as always,” I wrote, “is her understanding that one-size-fits-all advice fits no one. Instead, in Navigating the Messy Middle, readers will discover an empowering guide to finding one’s own way through the ups and downs of midlife, a time when seeking strength in connection, embracing the changeability of the physical self, and focusing on one’s real values and priorities can create a powerful moment of (finally!) becoming.”

Thank you to Ann Douglas for agreeing to answer some of my questions about her book, which I enjoyed so much, and which you can pick up right now from your favourite bookseller.

What more can we ask of ourselves but that we remain open to the opportunity to learn and grow as humans, both individually and together?

Ann Douglas

Kerry: This book was born out of a midlife shift for you after years of writing about parenting. How did it feel to make this pivot (scary? exciting?), how did you decide on where to land, and in what ways did your experience tie into themes and ideas explored in the book?

Ann Douglas: I had been feeling, for the past couple of years, that I was aging out of the parenting books category. (It’s hard not to feel this way when your youngest child is 25!) Now don’t get me wrong. I will always care passionately about parents and kids, and I will continue to advocate on issues affecting them. But in terms of being immersed in the really hands-on years of parenting? I am well past that stage, and so it seems like the right time to pass the baton to the up-and-coming generation of parenting writers. And there are a lot of them doing really amazing work.

In terms of deciding what would come next for me as a writer and a person, that was more exciting than scary. I’ve always been the kind of person who has a million ideas for creative projects, so it was simply a matter of seizing the opportunity to write about something else. In terms of landing on which “something else” that might be, there was a bit of serendipity involved. I’d had a rollercoaster ride of a journey through midlife, so midlife growth development was very much top of mind for me. And then, out of the blue, I received an email from my literary agent, telling me that she was dying to talk to me because she knew what my next book needed to be about. She needed a book about midlife and she needed that book to be written by me! We started brainstorming the possibilities and developing a book proposal. That casual conversation (in September 2019) resulted in a book deal (in February 2020, right as we were heading into the pandemic).

I guess the common thread in terms of my career as an author is my life-long fascination with human development: how we continue to learn and grow throughout our entire lives. Midlife has been a deeply challenging time for me, but also an opportunity for tremendous learning and growth. In fact, I can honestly say that it has been my favourite life stage so far.

I guess the common thread in terms of my career as an author is my life-long fascination with human development: how we continue to learn and grow throughout our entire lives.

Ann Douglas

I wanted to capture that sense of possibility in this book, while also endeavouring to keep it real. Because no one wants to read a faux positive guide to anything in 2022—not after everything we’ve been through over the past two-and-a-half-years. That’s what I tried to do in this book: to be both “fiercely honest and wildly encouraging,” as the subtitle of Navigating The Messy Middle indicates.

Kerry: Fercely honest AND wildly encouraging? IN THIS ECONOMY, ANN??? How is that possible?

Ann: If there’s one thing I’ve figured out at this point in my life it’s that you don’t have to settle for a single emotion. It’s possible to feel anxious, hopeful, discouraged, grateful, and frustrated all at the same time. Heaven knows I feel all those things simultaneously myself—and I do so on a regular basis.

So honest and encouraging? It’s definitely possible to have both those things at the same time. In fact, I feel like I’ve been focused on those two experiences for my entire career as an author: trying to write with honesty while at the same time offering encouragement. (Over the years, countless readers have told me that they really trust me and I think that’s why: that blend of honesty and encouragement.)

If there’s one thing I’ve figured out at this point in my life it’s that you don’t have to settle for a single emotion. It’s possible to feel anxious, hopeful, discouraged, grateful, and frustrated all at the same time.

Ann Douglas

Kerry: As the shape of the book emerged, what parts surprised you the most?

Ann: This book ended up being much more political than the book I had intended to write—and that my book publisher had intended to acquire. As I note in the opening pages of my book, “My agent negotiated the deal for this book in February 2020, just as the pandemic was beginning to be felt here in North America. The days and months that followed ended up changing everything, including me. I found myself launched into an eighteen-month journey into rethinking pretty much everything about my life. And judging by the depth of the conversations I was having with other women, I know I’m not the only one who was profoundly affected by this multi-layered experience of pause—the pandemic pause layered on top of the self-reflective pause that is so characteristic of midlife.” So that was definitely the biggest surprise for me: the approach I ended up taking in writing about midlife—that mix of personal and political. I have to give my publisher a lot of credit, for allowing me to write the book that demanded to be written (as opposed to the one I had planned to write). So, kudos to Douglas & McIntyre.

Kerry: Almost every argument I have about anything these days (with myself or others!) comes back to the fact that the answer or reality lies not in anything definitive or black or white, but instead somewhere in a grey area in between. The middle, as your book shows on a variety of levels, is a magical place rich with wisdom and opportunity, but yes, it’s going to be messy. How do you try to reconcile that and be comfortable in that uncertain and variable space?

Ann: I feel like the pandemic has been a masterclass in learning to live with uncertainty. It’s become pretty clear that nothing is entirely predictable and that there’s no simple solution to anything right now. Life is messy. Life is complicated. And yet, as humans, we have brains that are capable of sorting through that that messiness in a way that allows us to spot patterns and land on solutions. Maybe not perfect solutions. (Is any solution ever perfect?) But the kinds of solutions that allows you to steer clear of endless second-guessing, and regrets. The kind where you can say to yourself, “I made the best decision I could with the information I had at the time—and I reserve the right to rethink this decision next week. Or maybe even tomorrow?” What more can we ask of ourselves but that we remain open to the opportunity to learn and grow as humans, both individually and together?

It’s become pretty clear that nothing is entirely predictable and that there’s no simple solution to anything right now. Life is messy. Life is complicated. And yet, as humans, we have brains that are capable of sorting through that that messiness in a way that allows us to spot patterns and land on solutions.

Ann Douglas

About Navigating the Messy Middle:

Roughly 68 million North American women currently grapple with the challenges of midlife, faced with a culture that tells them their “best-before date” has long passed. In Navigating the Messy Middle, Ann Douglas pushes back against this toxic narrative, providing a fierce and unapologetic book for and about midlife women.

In this deeply validating and encouraging book, Douglas interviews well over one hundred women of different backgrounds and identities, sharing their diverse conversations about the complex and intertwined issues that women must grapple with at midlife: from family responsibilities to career pivots, health concerns to building community. Readers will find a book that offers practical, evidence-based strategies for thriving at midlife, coupled with compelling first-person stories.

Offering purpose and meaning in a life stage that can otherwise feel out of control, Douglas pushes back against the message that women at midlife are no longer relevant and needed, highlighting the far-reaching economic, political and social impacts of these messages and providing a refreshing counter-narrative that maps out a path forward for women at midlife.

Both a midlife love letter and a lament, Navigating the Messy Middle both celebrates the beauty and rages at the many injustices of this life stage and provides readers with the tools to chart their own course.

November 19, 2021

Angels, Hope, and High Stakes: A Conversation with Shawna Lemay

Shawna Lemay’s new book is the novel Everything Affects Everyone. You should be reading her blog Transactions With Beauty.

First thing: I am not interested in angels. Not at all, and so I’d wondered about Shawna Lemay’s new novel, whether it would have the power to sustain my non-interest in angels for the length of a book, but if you’ve ever read anything by Shawna Lemay (her blog, her fiction, her poetry, her essays) you’ll know that her work is never just about one thing anyway, instead a jumping off point for daydreams and reveries and musings on art and other golden things

Second thing: Everything Affects Everyone is a novel about questions, and boy do I have some, such as “How did your obsession with Bruce Springsteen influence this novel?” and “How you decide what kind of container your ideas will fit into, especially since there is such wide overlap and connections between everything you write?” and “What does it mean when you’re writing about questions and answers and dialogue, and yet YOU (Shawna Lemay) are imagining all of it, the illusion of a back and forth,” which kind of makes me start thinking of angels then, and reminds me of one of my favourite lines from the book about how maybe angels aren’t real, but the doubt is real, the wondering is real.

Everything Affects Everyone is wonderful and strange, rich and engaging, provocative and comforting, and filled with mystery and beauty. And what impressed me most about this book is how Lemay’s entire oeuvre is an essential context for appreciating this book properly, the way it fits into and extends her ideas and philosophy, which is utterly original, and inviting, which you can’t say about most things one might term a “philosophy.”

I am obsessed with Shawna Lemay’s obsessions, and the generosity with which she shares them, and the way that she can make me become vicariously obsessed with anything.

Even angels.

*****

Kerry: Can I start off with: How did your obsession with Bruce Springsteen influence this novel?

Shawna: I don’t think there could be a more perfect first question. I wanted to write a book where the stakes were high which I used to understand as maybe telling a story about the brutal state of the world, a story that was about escaping trauma or violence or incredibly difficult circumstances. I admire these kinds of high stakes narratives. I find them necessary. But there are other approaches.

It felt almost radical to insist on a narrative that looks at beauty and mystery and tries to move toward hope. Springsteen puts everything into his songs, and then also creates a narrative about his life, and lets that live around his work, too. Everything he does is part of the Springsteen story, I think. So, I like that. The stakes are high for Springsteen—he doesn’t shy away from the tough subjects, but he comes to them through music that is pure joy.

Springsteen says, “…you can change someone’s life in three minutes with the right song. I still believe that to this day. You can bend the course of their development, what they think is important, of how vital and alive they feel.” There are the things that you hope to do when you write a novel, but it will be received however it will be received. I would love to think that this book could go some way toward making the reader feel alive, feel invigorated.

It felt almost radical to insist on a narrative that looks at beauty and mystery and tries to move toward hope.

And then in an Esquire interview he says, “You’re trying to take all this misunderstanding and loathing, and you’re trying to turn it into love—which is the wonderful thing that happens when you’re trying to make music out of the rough, hard, bad things. You’re trying to turn it into love.” So while it may or may not come through in the novel, I asked myself, what if you just pour everything you have into this container called a novel, and just let it all turn into love somehow? What would that look like? Instead of the cockroach in Kafka’s The Metamorphoses, what if we had an angel? What if the act of imagining ourselves as an angel was just another way of imagining how to be human? What if we could be the angel who could guard each others’ “dreams and visions?”

Kerry: Oh wow, I love this, I asked the question because I honestly had no idea what your answer would be (and these are usually the most worthwhile questions to be asking in the first place), if it might be that there’s no connection at all, because it wasn’t like I read Everything Affects Everyone, and was thinking about Bruce Springsteen. But I know that your connection to him had been somewhat concurrent with your writing of the book, and (as somebody wise once titled her novel) everything affects everyone.

And I’m so glad you mentioned containers, because this WAS on my mind as I read your book. You who I first met through a blog called “The Capacious Hold-All.”

First of all, I feel like your containers are ever overflowing, anybody who’s read your blog, and your essays, your fiction and even your photography will know how connected they are, that these are all just different containers for your ideas and fascinations. Would you agree with this assessment? And how did you know/decide that Everything Affects Everyone was going to be a novel? I could see how it might have been poetry or nonfiction as well—and it even takes the form of invented nonfiction. So why fiction? How did you choose this particular container?

Shawna: I love your description of my work as being different containers for my fascinations—I immediately envision a still life of all sorts of clear glass jam jars, different shapes, with different facets, designs, sizes, filled with colourful liquid like potions—the light striking them and casting colourful shadows. And you’re right, I could have written a book of poetry or essays about angels. But I think a novel is the proper container for my angel fascinations because of the way that it holds mystery. All writing has this potential, of course. It had to do with time and movement, in the way that a viewer in a museum will look at a still life and experience it close-up and without moving very much, vs looking at a huge landscape or scene—the way you walk from one side of it to the other side, you move back, move forward. The text of a poem embeds in you differently than the text of a novel that you spend maybe days reading. Angels are like a flash of poetry but then there is all that living around an angel experience.

I think a novel is the proper container for my angel fascinations because of the way that it holds mystery.

Well, I say all this, but in honesty, the form just happened. It called. The writing proceeded organically and with surprisingly little calculation. I had Clarice Lispector’s words in my head about genre. She says, “Genre no longer interests me. What interests me is mystery.” But I had that in my head when I wrote The Flower Can Always Be Changing, too. (It’s the epigraph of that book). This book is in part an effort to be in conversation with Clarice Lispector, who for me, as soon as I learned of and read her work (which I can only read in translation) made my hair stand on end. I think Rumi and the Red Handbag is in conversation (bold claim) with The Hour of the Star and maybe this book is in conversation with The Passion According to G.H. Or maybe A Breath of Life. This sounds grandiose but I really didn’t want to die without having written this novel and published this book. I wanted to fill that container with my all.

Kerry: How did angels start to happen for you?

Shawna: I have intermittently been called an angel my whole life. I know that this is because as a child I had white blonde hair. If you had asked me as a kid what an angel was I probably would have answered “a goodness.” And I knew I wasn’t necessarily that, so immediately: a contradiction, a “huh!” As far as I knew back then, all the adults were calling all the children angels. One of the more memorable times I was called an angel was by the Irish poet Michael McCarthy who died in 2018. He recounts our meeting in his posthumous book, Like a Tree Cut Back. The year was 1995. Michael writes: “On my second day in Edmonton I visited a bookshop in the local mall. A young, tall woman approached me and asked if she could help.” He had this otherworldly quality, and I would find out until later that he was a priest, and that he was recovering from cancer. He would win the Patrick Kavanagh Award for the book of poems he wrote in his time in Edmonton. I would introduce him to the poetry community and because of that he often referred to me as his angel. But when I met him, he seemed the angel, or at the very least a magical bird. It was the middle of winter. He took off his toque in front of the poetry self, and his grey hair stood on end with the static. The air around him crackled.

Another one of the angels of my life is Barb Langhorst. I can’t remember the year but she was teaching at St. Peter’s College in Saskatchewan, and was using the story by Gabriel Garcia Marquez titled, “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.” She sent me a copy because she knew it would interest me. I became obsessed with the story which can easily be found on the internet these days, but also in his Collected Stories. As soon as I read it I knew it would find its way into my writing someday. But it turned out that Amanda Leduc wrote The Miracles of Ordinary Men first, an amazing book. And then in 2017, Peter Darbyshire wrote his edgy and super cool Has the World Ended Yet?—which is full of angels. But by then I realized (and was already writing this book) that you could sit a dozen people in a room and say, write about angels, and they’d all write something completely different. So that was a good moment.

I realized that you could sit a dozen people in a room and say, write about angels, and they’d all write something completely different. So that was a good moment.

Meanwhile, people who come into the library where I work continue to call me an angel from time to time. (Maybe now that I’ve said that it won’t happen again). A couple of weeks ago, though, on a phone call (so it wasn’t about the blonde hair) I looked something up for a person who then said repeatedly, you are an angel, a real angel. My book was in the stores at that point and it honestly really shocked me. I do, funnily, get that fairly often at the library, but then I’m pretty sure all library workers get that.

In short, though, I would say that on average throughout my life I’ve been called an angel by someone once every couple of months. When I say it though, man, that sounds weird! But there it is. It always startles me. It’s a shock. Electricity! Whenever someone calls me an angel I always assume they’ve got it backwards, and they’re the angel.

Kerry: What’s the connection with libraries and angels? (I love, by the way, that your novel references City of Angels, and that it’s not just fancy German art films all the time. The lack of pretension with which you talk about rarefied things is so inspiring, plastic bags and grocery store flowers…)

Shawna: I think most writers and readers have had what is known as a “library angel” experience in “coincidence theory.” (Which in fact, I had done no looking into until just now). There’s a book by Arthur Koestler that details the phenomena anecdotally, apparently. (Perhaps that book will fall into my path now that I’ve mentioned it). It’s just the phenomena, though, of a book finding you in whatever way as if you have conjured it, and there are tales of books falling off the shelf and it being the precise one that person needed or was hoping for. Have you ever had an experience like that?

I’ve had a few of those library-angel experiences, though I tend to just put them down to serendipity, or the fact that because I spend so much time working in a library that this is just bound to happen. But people regularly talk about this sort of thing happening in library-world.

And if we can think of angels less as figures from the history of religion, and more as either paranormal or secular manifestations or projections of our unknowing or as non-denominational spiritual messengers (so many possibilities!), then it makes some sort of sense that they end up in a library. In the secular world of my novel, the angels wouldn’t be drawn so much to cathedrals but to libraries because this is where people seek—libraries are full of people seeking information, help of so many different types. If angels are primarily messengers of one sort or another, then a library is a pretty great place to impart them.

In the secular world of my novel, the angels wouldn’t be drawn so much to cathedrals but to libraries because this is where people seek. If angels are primarily messengers of one sort or another, then a library is a pretty great place to impart them.

There’s a lot of literary and filmic precedence for angels in libraries, too, so I liked echoing that. As you mention, scenes occur in City of Angels and Wings of Desire. But there are library scenes in Lucifer, and in Constantine, where Tilda Swinton plays the angel Gabriel. There is also the amazing Charles Simic poem which he wonderfully allowed me to use in the book.

There is the fabulous quotation by Caitlin Moran about libraries, where she says a library “is a cross between an emergency exit, a life raft and a festival. They are cathedrals of the mind; hospitals of the soul; theme parks of the imagination.” And in my experience, a lot of people come to libraries not so much to be healed, though that also happens a lot, but to find hope. Just being in a library is a kind of message, so there’s that too. It makes sense that angels would congregate in such a place.

Kerry: Sometimes you ask a question and the answer you get is more wondrous than you’d ever supposed it could be. I love this, Shawna! And I suppose I have experienced “library angels.” I used to work in a library when I was in university, and there are so many books that came into my life because they happened to be on my shelving cart, or because they happened to be filed beside a title that was. I suppose that’s less random, really, but it was such an inspiring method of discovery.

I also remember doing “shelf reading,” which was going into the stacks to read the spine of every single book to ensure that the books were in order, which I once upon a time supposed was a kind of make-work project, but now I see we were being library angels ourselves, rescuing volumes that might have become fallen or misfiled, and needed to restored.

And now I am thinking of angels as agents of order? Or disorder?

Shawna: I love that you worked in a library when you were in university! I did, too, and I don’t think I knew that about you. I worked in the science library for five years which was such an interesting place for an English major. Anyone who frequents libraries though has experienced the angel of shelf reading! They just might not know that.

One thing I love about working in libraries, and I guess I’ve been in one library or another as a worker for more than twenty years of my working life, is watching the body language of people in libraries. I’ve internalized a lot of it, but I think I could write a whole book on just that, which would of course include photographs! There’s an utterly unique way of “being” in a library, is my theory.

Kerry: I am thinking too about your own preoccupation with questions, with dialogue—so much of your book is written as questions and answers, you exploring the power of this sort of exchange. And what is different, or perhaps even just the same, because you, the fiction writer, happen to be questioner and answerer both here?

Your novel also made me think about the title of Miriam Toews’ novel Women Talking, which would also have made a good title for Everything Affects Everyone.

Is asking you if a fictional conversation is as potent as an actual conversation sort of like critiquing a still-life because you can’t eat it?

Fittingly, or not, I don’t even have a question here, Shawna. Except maybe, “what say you?”

Shawna: Well, to immediately circle back to libraries, I think I’ve just realized, because of this conversation that we’re having right now, that so much of the book is informed by my experience of what we like to call in the biz, “the reference interview.” Wow. And so what every library worker knows and works toward, and really this is one of my life’s main raison d’êtres, is the perfection of the reference interview. Which is ever unattainable, a work in progress, the holy grail of library work. Because, as in most conversations, a lot of what happens is sidelong. Sure there is often the straightforward person who comes in wanting X book, asks for X book, and walks out with same. Wonderful, that! But often the person arrives looking for something that they can’t say, or don’t know how to say, or want to say but are too uncomfortable to say, or don’t even know that they can ask for this thing that they need. So, it is this really delicate back and forth, that must be purely openhearted, and orchestrated to not presume, to not overextend, to probe but with good intent, with a mind to privacy, a mind to empathy, and with a great deal of instinct, as to when to be blunt, or ask the really dumb or super open ended questions, when to be silent, when to nod. It’s an exercise in hope and humility and curiosity and must be filled with a genuine interest in the human before you.

So, it is this really delicate back and forth, that must be purely openhearted, and orchestrated to not presume, to not overextend, to probe but with good intent, with a mind to privacy, a mind to empathy, and with a great deal of instinct, as to when to be blunt, or ask the really dumb or super open ended questions, when to be silent, when to nod.

So I guess all of this to say, that I’m always thinking about how we can have a better conversation, in the aforementioned circumstance, but also in other areas of our lives. There was a recent interview on On Being, with the always wonderful Krista Tippett in conversation with Priya Parker, about gathering. They talk about how a gathering is improved by the preparation beforehand, when we guide the invitees on how to show up. Like, let the people know what they’re showing up for, what’s the purpose! What’s the framework? There’s an intentionality. They quote another favourite author of mine, John O’Donohue, that an intentionally extended invitation allows us “to cross our thresholds worthily.” And a conversation can be a threshold, too. How do we have better conversations? How can conversations be transformational? How do we transform in conversations?

I was reading recently (ack I can’t remember where) about the difference between an answer and a response, and how an answer will potentially close things down, but a response will keep things open. And isn’t that interesting to ponder?

Regarding the fictional conversation. This is interesting, because I think I was drawn to that form partly because in real life, I’m not the best interview subject, haha! I’m not. If we were sitting here talking I would not be getting half this stuff out, because I usually get so nervous, my brain shuts down. So maybe writing fictional conversations is a way to redeem this failing? Maybe. But it also allows the writer to be in two minds about something, to embrace more than one possibility, and to even posit things that they don’t necessarily believe, but want to hear “out loud” as a sounding board of sorts.

Kerry: Oh, yes! I often think of something you wrote awhile back: “Consider the opposite.” That idea is a kind of touchstone for me. How would you say that Everything Affects Everyone is a demonstration of this very idea?

Shawna: When I was writing Rumi and the Red Handbag, part of what got me started was thinking about what a literary critic had said, about how men go on quests, but women go on errands. And then I got thinking about errands as quests, the handbag as the grail, which led to the central question of that book which is, What are you going through? When we start to wonder about the opposite of one thing, quest vs errand, for example, we then begin to question if those two things are really in opposition and how.

So with Everything Affects Everyone, I was very much inspired by the Marquez story, “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” and wondered if it could be young women with you know, just beautiful wings. But then what kept coming back to me was Kafka’s Gregor Samsa and his transformation into probably a cockroach. And wondering what happens when instead of a cockroach, one becomes an angel. And what if wondering about what it would be like to become an angel were really just another way of imagining what it’s like to become a human, or a better human, or just to become who we are. And isn’t that a marvellous possibility?

So I love that you have held that phrase, “consider the opposite,” because while it’s not explicitly in the book, it has meant a lot to me, too!

And what if wondering about what it would be like to become an angel were really just another way of imagining what it’s like to become a human, or a better human, or just to become who we are. And isn’t that a marvellous possibility?

Shawna Lemay

October 13, 2021

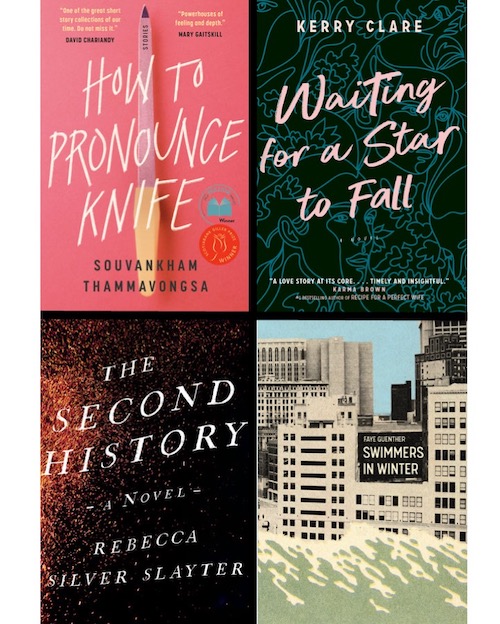

Class Reunion: ENG 369Y 20 Years Later

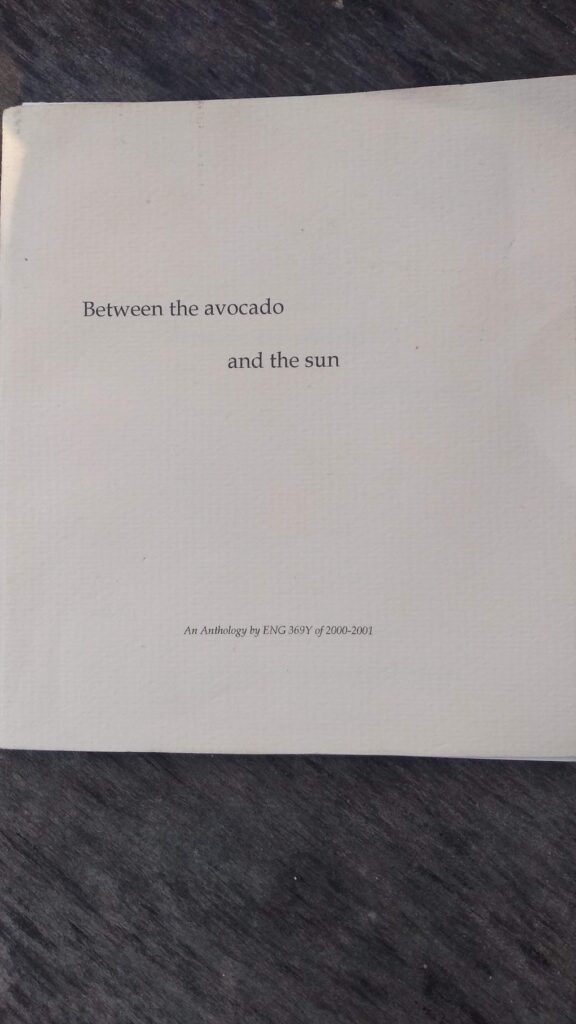

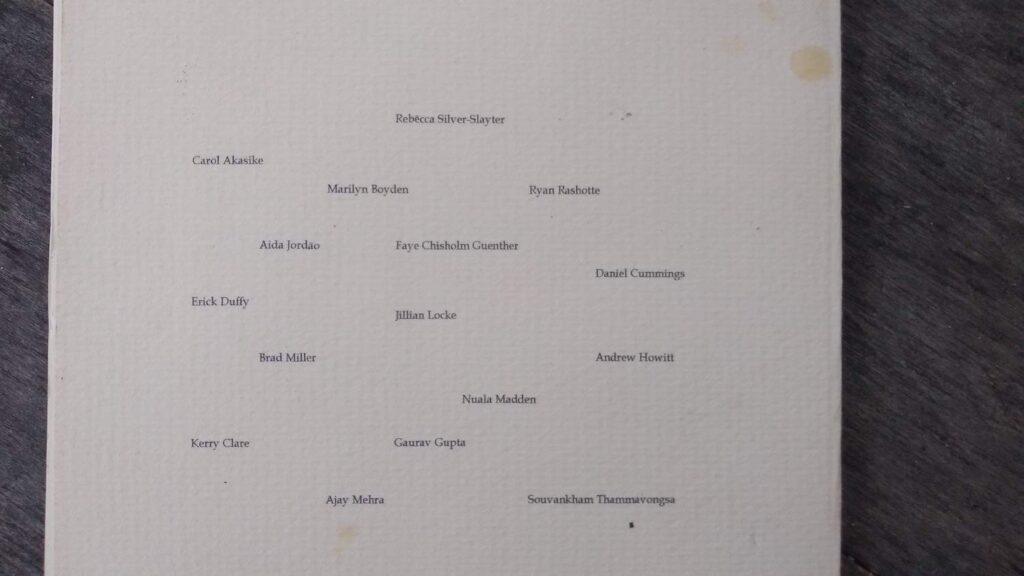

During my third year of undergraduate studies, from 2000-2001, I was part of ENG 369Y, a creative writing workshop led by Dr. Lorna Goodison through the Department of English at the University of Toronto.

For so many reasons, many illuminated below, this class would be an unforgettable experience, though it seemed especially remarkable when—two decades later—four of us from the class would all be publishing books within the same year and a bit.

- Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife was published in April 2020, and it was awarded the Scotiabank Giller Prize that year, as well as the 2021 Trillium Book Award, among other accolades.

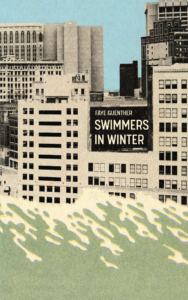

- Faye Guenther’s Swimmers in Winter came out in August 2020, and it has been a finalist for both the Toronto Book Award and the 2021 ReLit Award.

- My book, Waiting for a Star to Fall, arrived in October 2020, and the Montreal Gazette called it, “Subtly complex […a] romantic drama tailor-made for the #Metoo age.”

- And Rebecca Silver Slayter’s The Second History found its way into the world this summer, with no less than Lisa Moore writing that it’s “one of the most honest renderings of romantic love I’ve ever read. [A] truly mesmeric story, tender, unflinching, quakingly good.”

To me, the serendipitous occasion of our new releases after all this time seemed like an splendid opportunity for us to reconnect and reflect on our time together, as well as so much that we’ve learned about writing in all the years since then, and so the four of us shared our thoughts and ideas via email.

tell us about 20 years in the writing life, about the trajectory of your writing life since our class together in 2000.

Kerry Clare: I don’t think I had a focussed relationship to writing at all in the first ten years after our class together, even as I completed a MA in Creative Writing at the University of Toronto from 2005-2007. There is a line in Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life that I may have misremembered, but it’s about a superficial idea of writer-dom being analogous to one admiring the way one looks in a particular hat, and I always thought she was talking about me, which was mortifying.

When I finished graduate school, I worked for two years reading financial documents all day long, which was not fun, but gave me stability and a salary, though little in the way of creative inspiration. It also gave me parental leave benefits, which I used when I had my first child in 2009, and becoming a parent really seemed to up the stakes for me writing-wise. I became invested in the world in a more meaningful way, and therefore had more to write about. My first big success in writing was an essay about new motherhood I published in 2011, and this led to my first book, the essay anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which I edited and was published in 2014.

At this point, I wasn’t sure that writing fiction was going to be my destiny, and was even making peace with that (throughout this entire period, I’ve been blogging, which has been a creative lifeline), but then something clicked shortly after my second child was born and I finally figured out how plot works. My first novel, Mitzi Bytes, was published in 2017, and I’ve been writing them ever since, and though I am constantly terrified that one day I won’t know how to do it anymore, it seems to keep happening.

Souvankham Thammavongsa: I am not a very good example of a writing life because my trajectory isn’t a simple one and it is not for everyone. I don’t think anyone would want it. I worked for fifteen years in the research department of an investment advice publisher, I counted bags of cash five levels below the basement, I prepared taxes. This work helped me write what I want and it didn’t take away my desire to write. I still have that from 2000, this desire to write, but it wasn’t anything someone taught me.

Faye Guenther: I stayed at the University of Toronto to do undergraduate and graduate degrees in English. Then I went to York University and did a PhD in English. While I was a student during those years, the jobs I had to support myself weren’t related to writing, but they showed me things about the world and this is useful to a writer. I’ve found that no matter what you do, the key is to make the time to write. My writing life has also been shaped by who I’ve met along the way, including fellow writers. In 2017, I published a chapbook of poems and short fiction, Flood Lands, with Junction Books. In 2020, I published a collection of short fiction, Swimmers in Winter, with Invisible Publishing.

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

Rebecca Silver Slayter

Rebecca Silver Slayter: I decided to stop writing not long after that workshop. I think, to reverse what Souvankham said, I worried my desire to write might be something someone had taught me. That I had lost track of why I wanted to write at all.

So I stopped for a year. Or two. Or three? It felt like forever because I was 20-something and everything was forever.

And meantime I decided to make my life and work writing-adjacent. I interned at Quill & Quire and The Walrus. I worked for a startup children’s publisher. I did odd jobs to complete the financial math, yardwork and errands. Eventually I was hired for my dream job, working as managing editor for Brick literary journal.

Sometime in the midst of that, I met my husband, and told him, proudly, how I had made the tough, mature decision to give up writing, and he listened and nodded and then said, I know you are a writer, with such certainty that I didn’t know how to doubt him and I began writing again. And I found to my great joy what I had been missing in those earlier writing years; a desire to write that easily overtook the desire to be a writer.

I did graduate studies in Montreal, where I wrote the first draft of my first novel, In the Land of Birdfishes. When I graduated, I returned to Nova Scotia, and bought a house for a song in Cape Breton, which I will be renovating for the rest of my earthly days.

This is for me a very good place to write, near the ocean and the highlands, in a community where music and storytelling are woven into everyone’s daily life. Here I published my first book and then wrote and rewrote and rewrote my second book, which was just released this summer: The Second History. It took me eight years from first draft till now, mostly because I tried to write it faster than I’m able to. It turns out I’m a writer who needs to take my time…

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

what was the best thing the writer you were in our classroom had going for them? And what writing advice would you give that previous incarnation of you? (Though would you even have taken it?)

ST: My intuition. I listened to everyone, and knew when not to. This taught me how to pick through edits. When we see edits, sometimes it’s about the person and their life experience and it doesn’t mean they are right or know but you have to be generous and allow them to have their thoughts.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it. I want myself to encounter and work through those difficult and lonely moments. I don’t want anyone to hold my hand or do me any favours or make it easier or easy. I like the difficult, and I want to continue with that difficulty.

RSS: One of my clearest memories of that workshop was of Professor Goodison saying, as we discussed one of my poems, “You come from preachers, right?”

I was tongue-tied with confusion. “What?”

“Your people, they’re preachers, right?”

I had absolutely no idea what she meant. “No….” I stammered.

“Then why are you preaching at me?” she asked.

Oof. Caught. I was constantly preaching. Trying to find a much-too-simple way of understanding much-too-large things. I had a weakness for sentences that began like “Love was…”

I think somewhere in this is both my weakness and strength as a writer (probably as a human too). It is writing-in-bad-faith to just polish up pretty turns of phrase that sound truish. To go around making tidy summaries of untidy things. But… I think if I mine deeper I can find underneath that impulse what drives me to writing still, and to reading itself… The sense that there is some luminous other way of noticing the world that will make it brighter, stranger, more visible. That certain words can be incantatory, a pathway to looking again and seeing more.

I have two small children, and have found it astonishing to witness language dawn within a person who formerly had none. How each child altered a bit around the language they used. How they learned what it was then to be nervous, even tired, even thirsty. How what began as the ragged, indeterminate longing of a baby’s howl became so clear, so precise, so unmysterious. And I miss a bit the mystery. The wonder of watching a peer being who doesn’t know what yesterday is. But I think there’s another way that language can give us back what experience has made ordinary. And I think that’s what I was searching for twenty years ago and search for still, but with a few degrees more purpose. And a lot more joy.

So I would maybe advise myself something like this: First, don’t write any more poetry. You are very bad at it. And for a time, don’t write at all. Wait until the desire to write is something you have to resist. Wait until it wells up in you. And then go find the joy of writing words that make you look again, more deeply.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it.

Souvankham Thammavongsa

FG: I remember being openhearted and creative. The writing advice I would give my earlier self is to be bolder. I think when boldness is combined with a practice of being open with yourself and to the world, there is a sharpening of creative focus that can happen and a strengthening of creative perception, no matter what challenges life brings.

KC: The writer I was in our classroom had no idea how much she didn’t know, and far more confidence that she deserved to have, and I’m so happy she did because being 21 is hard enough. I was not a serious person or a serious writer AT ALL. (I remember that Souvankham appeared to be both, and it was such a powerful example for me, though I think I was still too young to fully appreciate it.)

What a tremendous opportunity to develop my skills that class should have been!! But I did not work all that hard, honestly, too busy checking out my look in the hat, remember? I mainly wrote poetry because you could finish a piece in a few minutes. This did not mean my poetry was good, however, although I think sometimes some of it was.

If I could give that writer I was any advice it would be to write something REAL, instead of something you think sounds like something that could be real. (And find writers you love, instead of reading all the writers you’re supposed to love.)

For the record: I would not have listened.

what roles have literary journals and small presses played in your writing career?

RSS: I know literary journals and small presses better as a worker than as a writer. But I am shaped permanently by my years at Brick literary journal, and by the trips I made then, twice a year, to Coach House Press, where the journal was designed at that time.

The Coach House basement was a kind of church I visited like a disciple of those beautiful machines for cutting pages and laying type … and of the people who made them run and knew the stories of an older Toronto and the mesmerizing adventures then had by not-yet-famous writers. In a way that is both corny and essentially true to me, that is what I feel a tiny part of when I write: all the people in all those tiny offices and studios and nooks making small-press books and magazines; their labours of love, their care and bravery, those parallel arts of ink and paper, alongside those of prose and plot.

They taught me what was foundational to writing; the courage and the care of the work. And the kinds of community it can build.

FG: Reading literary magazines gave me an awareness of community. They were the first space where I was published, and I know this is true for many writers. Smaller presses often foster innovative and ground-breaking work. They frequently publish voices and stories that historically have been marginalized. I think smaller presses are important for energizing and sustaining a vibrant creative culture.

My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance

Kerry Clare

KC: My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance, especially in the wake of the novel I’d written for my Masters thesis that went nowhere (because it was boring!) because I was really feeling kind of discouraged, and then this message from the universe arrived suggesting maybe I should keep going after all. In the next few years, I would publish pieces in TNQ and other journals, and the high of an submission being accepted has never diminished for me. And then Goose Lane Editions, a remarkable Canadian indie press with an impressive history, published The M Word, and did the book such justice. Without literary journals and small presses, I’d be nowhere.

ST: Literary journals teach you things a writing class or editor or a dear friend and family cannot. They don’t love you and are not beholden in any way. They teach you about rejection—what that feels like, what to do with it. They are often the first place where we get to see ourselves in print. It’s important for a writer to understand the difference between seeing yourself in print and publishing a book. They are not the same.

what are your favourite memories of our class?

ST: I remember the talent and fun. There were so many writers in that class who are more talented, more ambitious, more interesting…but they aren’t here, or with books. They became lawyers and engineers and professors. I always keep that in mind. Having a book doesn’t mean I am good.

KC: I have so many memories! I don’t know if we were particularly interesting as a group, or if it was the work of Professor Lorna Goodison in creating community, or just the particular mix of experience and personalities in our class, but I felt very connected to everyone. I think we were a well written cast of characters.

I remember Souvankham on the very first day, and how she impressed me so much with her sense of herself. I remember we had to write a poem inspired by postcards, and mine had a field of sunflowers and said, “Welcome to Michigan,” and I wrote a poem with the line, “I won’t forget the motor city.” I remember REDACTED who wrote a poem with the line, “Let’s make love in the astral plane,” and I was seriously impressed by how sophisticated he seemed. And someone else who wrote a poem about someone sucking on her toes while listening to Robbie Robertson sing “Somewhere down the crazy river.” Everyone seemed to be having a lot more sex than me. (One could not have been having less sex than me.)

I remember Faye seemed especially interesting, partly because she seemed kind of badass with a shaved head, and we always sat in opposite corners of the room. And how I was in love with the name “Rebecca Silver Slayter,” which belonged to the woman who often sat in the same corner as me and whose work I felt very drawn to.

I think it’s kind of wonderful that in addition to the four of us, plenty of others in that group have gone on to very interesting careers in academic, television writing, and more.

One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

Faye Guenther

FG: I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from our teacher Dr. Lorna Goodison. One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

RSS: This sounds like very cheap, opportunistic flattery, but honestly, though I remember well many of the talented, interesting writers in the class and their poems and stories, what I remember most clearly is the three of you.

I remember how beautifully Souvankham’s work was always laid out on the page in lovely, tiny type—the form so perfectly echoing the work itself, the grace and economy and polish of her words; how her work seemed always already complete, and I was stumped on how to write any feedback that didn’t just feel like tampering.

How Kerry’s writing was funny and powerful at the same time, and I hadn’t even known that was possible. How she seemed so at home both on the page and in the classroom, warm and open and at ease in a way that awed me. I remember Faye’s compassion for her characters, their rich interiority. How reading her stories felt like someone whispering in your ear, that intimate.

My strongest memory of the class was the first one. When we went around the room and each offered up our names.

Souvankham was near the end, seated at the table perpendicular to the one where Professor Goodison sat.

After she said her name, Professor Goodison asked, “So what do you want to be called?”

I was caught off guard by the question, but Souvankham answered clearly and immediately. Without blinking or skipping a beat, she said: “I want to be called a writer.”

Professor Goodison looked at her and Souvankham looked back. Then she said, “I’m going to call you Sou.”

And I was as astonished as if Souvankham had wafted out of her seat and up into the air between us. I was at that time so uncertain, so full of twenty-one-year-old desires to be interesting, to be brave, to be invisible and/or famous. I would have probably told Professor Goodison she could call me whatever she wanted. Or tried to guess what she might prefer me to be named.

Year by year over these last twenty, I get a little closer to what Souvankham already had then. That certainty. That clarity of purpose and identity as a writer that struck me silent when I was twenty-one.

April 9, 2020

A Conversation With Tara Henley

Like many of you, I found myself unable to read as this crisis arrived in our lives, perpetually in a panic, scrolling news feeds instead. Not being able to read, however, only compounded the trouble I was in, because if I’m not a reader, then who am I? And it was Tara Henley’s new memoir LEAN OUT: A MEDITATION ON THE MADNESS OF MODERN LIFE that brought me back to books again, a gorgeously written memoir that is perfectly timed for our current moment. Henley was kind enough to answer some of my questions about the book, so please read on to learn about how Madeleine L’Engle’s books expanded her vision for her life, what are the limits of self-care, and how “right now we’re seeing in stark terms the price we all pay for inequality.” I love this book so much.

June 18, 2019

A Conversation with Kate Keenan

I met Kate Keenan about two years ago when our children were enrolled in the same swimming class and she made an immediate impression on me as she spent the class entertaining her other child with hand-clapping games—”See See My Playmate” was a favourite. We finally started talking, which was great because I had decided I wanted to be her friend, and then I ended up giving her a copy of my book after a conversation about books and reading, and then the next week she brought me her CD (“I’m in a band,” said this super-cool mom—who, it turned out, had an intergalactic alter-ego—like this was no big thang).

So what I’m basically saying is that I’ve been a huge Kate Keenan fan since “See See My Playmate,” and since then I’ve enjoyed watching her as part of the Space Chums (including in their show at the Toronto Fringe Festival last year).

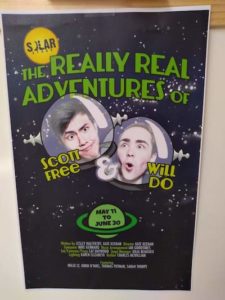

Her play, The Really Real Adventures of Scott Free and Will Do (which she co-wrote with Lesley Halferty)is playing at Solar Stage at Wychwood Barns until the end of June. We saw it on June 9, and loved it—and it made me realize that there was lots about her career in theatre, writing and motherhood that I wanted to ask her.

*****

Kerry: Can you tell me the story of The Really Real Adventures of Scott Free and Will Do—when did you (co) write it and where was it performed?

Kate: To tell you the story, I could start all the way back in high school at Etobicoke School of the Arts where I was lucky enough to be cast in “Les Goons” a Commedia dell’arte troupe run by our teacher John Glossop in the Lagoon Theatre on Centre Island. Best summer job ever. When Mr. Glossop stopped running “Les Goons” I was in grade 10 and some friends and I started our own children’s theatre company, “Island Treasures” in the same theatre. It was like a dream clubhouse/lemonade stand! And a real crash course in running a business…

“It was like a dream clubhouse/lemonade stand! And a real crash course in running a business…“

Anyway, after theatre school, I quickly got sick of having to wait to be cast in other people’s shows. So, knowing the theatre on the island was sitting empty, I started a company, “Shrimp Magnet Theatre Co.” with a bunch of friends from George Brown. We couldn’t afford the rights to any published plays, so we wrote our own—and I quickly became more passionate about writing than acting, which is saying quite a lot…

We would do the shows 6 days a week, 4 times a day (6 times a day at the beginning, until we came to our senses). We’d have rotating casts, but I usually worked about 5 days a week (along with running the operation with my best friend and co-author Lesley Halferty). You know that old thing where if you caught your kid smoking a cigarette, you locked them in the closet with a carton and wouldn’t let them out till they smoked them all? Okay, I guess that was actually a 1950’s thing and no one I ever knew was actually subjected to that but we all heard the stories… Anyway, it felt like that doing those shows. If a line was clunky, or a bit wasn’t working, you’d have to do it over and over again, watching audiences lose attention in the same spot, show after show. At the end of the summer, we were gasping to re-write!

“If a line was clunky, or a bit wasn’t working, you’d have to do it over and over again, watching audiences lose attention in the same spot, show after show.“

And we did. We usually did shows at least two years in a row—and I think it made us really, really good at knowing what worked and what didn’t and how to be unsentimental about stuff.

Oh dear, I’ve just noticed that didn’t really answer your question! So! Down to the nitty gritty! We created Scott Free and Will Do the summer of 2003, I think! I was 26. (and now I’m 42. WTF?!?) We performed it on Centre Island that year, then we did Toronto Fringe. Then Canmore Kid’s Festival, then Winnipeg Fringe. (And in between we cobbled together a tour in my parents’ minivan—4 actors, one Stage Manager, an entire set and all our luggage for over a month! We traveled to Sault Ste. Marie (where we stayed with my friend Trish’s family and partied under the Royal Order of the Moose), Atikoken, where we stayed in an old elementary school and played an epic game of hide and go seek all night, then in Geraldton, where we billeted with amazing people and a pet turtle, and also Thunder Bay, with lovely Rita and amazing Hoito pancakes.

Some incredibly talented people have been in the cast, including Keith Barker, who now is A.D. of Native Earth and Rebecca Benson, a prof at Carleton University. In particular, we can never forget C.J. Schneider, George Brown Theatre colleague who was a natural clown and a force of nature and comedy. A bunch of nonsensical/brilliant lines in the show are his (mostly and luckily because we could not control him) including “Boingy booing chop chop” and “its crazier than eating a dill pickle popsicle on a Wednesday that’s also a Tuesday!” C.J. died way too young of cancer in 2010. We miss him so much it hurts. Also the brilliant Matt Olmstead and Mark Purvis.

Kerry: What was it to bring the show to life again? What surprised you about this experience?

Kate: We brought the show to life at Solar Stage twice before when they lived in North York. This time around we had added two new actors (the moms). There were many layers of mind-blowing weirdness for me. First of all, it’s SUPER weird to revisit a show I worked on in my late twenties, with actors in their late twenties when I am now in my EARLY FORTIES! It was like a strange time warp!

I still felt EXACTLY THE SAME, but to the actors I was an elderly MOTHER OF TWO! I kept having to remind myself that I was not the same! To their credit the actors treated me as a total equal, and I really did feel younger while we were rehearsing. I was even joking more like I did in my twenties—it was really strange! And the second thing that blew my mind were the new jokes we found. I mean, I can’t imagine how many times I’ve done this show and STILL, this time, super obvious jokes would pop out that I guess had been staring us in the face for years! That made it so fabulous to rehearse again—finding new moments that ever-so-slightly improved the play. My mom and I have a joke that we can’t just enjoy a joke, we have to constantly be improving upon it. Turns out this is an obsession, and hopefully a career for me!

“It’s SUPER weird to revisit a show I worked on in my late twenties, with actors in their late twenties when I am now in my EARLY FORTIES! It was like a trippy time melt!“

We have done the show for so many audiences but I will always be blown away that we always get new, mind-blowing responses from the crowd. It was such a refreshing thing, right out of theatre school, to be performing a play so many times that you had to work to keep your energy up, as opposed to your nerves down. One thing that always kept me alive and engaged was the excitement of what the audience would bring to the show. And they are still bringing brand new things! For (a slightly unsettling but still interesting) example, just recently when the actors asked the audience, “How do you know you’re real?” A child replied, “because we could die.” Not the usual kids theatre fare, but pretty amazing…

Kerry: You were writing for children before you had kids of your own. Has becoming a parent changed the way you relate to children? Are there things you know better now? (Or vice versa?)

Kate: How has becoming a parent affected how I write for children? Well, I think it’s allowed me to cheat. Honestly, before I had kids, I felt I remembered what it was like to be a kid myself. I feel further away from that now—can I blame the sleepless nights with my babies? I dunno, but I do feel grateful that parenthood has allowed be to experience childhood all over again with a new perspective. Funny, our show has two moms and two kids in it. If anything, I think I now approach the mom characters less as caricatures and more as real humans! The kids have stayed real…

“If anything, I think I now approach the mom characters less as caricatures and more as real humans! The kids have stayed real…“

Kerry: What do you love about writing for children?

Kate: My love of writing for kids is twofold. Firstly, I’m super insecure, so writing for kids gives me a flimsy excuse not to “take myself too seriously.” It gives me the permission to be free and not judge what I’m writing. But actually that’s bogus, because I believe that writing for kids is as difficult and sacred as writing for adults—my ego just needs a weird cop-out.

Secondly, I love the honesty of kids. I love that when I’m performing for them, I know when they’re bored. There’s no fakery, so the feedback is super accurate and helpful. Being able to trick my ego and being given such robust feedback has helped my writing immensely!

Kerry: What other creative projects are you up to these days?

Kate: Right now I’m writing a bit for children’s television, still with my bestie and co-author of Scott Free & Will Do, Lesley Halferty—shows that have yet to air, but I will keep you posted! I’m also 1/3rd of an outer-space rock band for kids called Space Chums with Ian and Lindsay Goodtimes! This is where I get my acting and singing itch scratched and my general goofing around with kids itch as well!

And my other passion project is a podcast for kids where I write stories on demand from “story seeds” kids give me. I’ve only just started out, but so far I have a story for my eldest daughter Elwyn, called “The Lights in the Forest” and one for my youngest daughter Lucy called “The Ballad of the Barn Owl” My plan is to record them and eventually publish them.

October 13, 2016

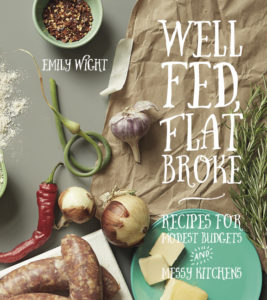

On Blogs and Food Blogs: a Conversation with Emily Wight

Emily Wight is author of the cookbook, Well Fed Flat Broke, which is the cookbook that taught me what people are talking about when they talk about reading cookbooks for pleasure. She is also the longtime writer behind the blog of the same name, and I really admire her work and her perspective on blogging.

Emily Wight is author of the cookbook, Well Fed Flat Broke, which is the cookbook that taught me what people are talking about when they talk about reading cookbooks for pleasure. She is also the longtime writer behind the blog of the same name, and I really admire her work and her perspective on blogging.

I’d always wondered if my own philosophy of blogging (that blogging should be easy, fit nicely into your life, never be a chore…) was relevant to food blogging. Emily was kind enough to answer my questions about food blogging, and blogging in general, and what it means to be an old school blogger still at it in 2016.

*****

Dear Emily,

I really admire your blog, your book, and all you do, and it occurs to me that you might the perfect person for something I’ve been wanting to do for a while. I teach a blogging course at UofT and think about blogging a lot, have all kinds of theories about blogs as a radical space, for women in particular. and how blogs have certainly been hijacked by commercial interest. My favourite thing about blogs is there inherent messiness, how they’re works in progress, an exercise in making it up as you go along…

But I also know that this doesn’t quite work for food blogs. A lot of work is required for a food blogger. Whereas I see a blog as a great place to practice the art of imperfection, a food blogger has to get it right or else she’ll be messing up her readers’ dinners. There is also the nature of sponsorship…

Anyway, I would be really interested in reconciling my own ideas about blogging with the realities of food blogging and expanding my understanding of blogging in general. Would you be willing to engage in a back and forth email conversation over a few days to get some of these ideas flowing?

**

EMILY

EMILY

I’d be happy to help! But also food blogs can be messy and alive, it’s just harder to find them now. I really like Poor Man’s Feast and The Yellow House, but to be honest I’ve really moved away from reading a lot of food bloggers. By the time fall comes, I never want to see another recipe for squash soup as long as I live. I think the “why” behind food blogging has shifted from when I started one million years ago in 2007/08, certainly.

**

KERRY

Okay, so here is my first question. My whole deal is that blogging should be easy, it shouldn’t be a chore. If blogging is hard and taking up too much time, I preach, then you’re doing it wrong. But with food blogging—I suspect and as I’ve been told—there is recipe testing required, you can’t do typos (or else you can end up with a tablespoon of salt when it should have been a teaspoon). It’s a whole different game. Not to mention staging required for photographs… Has this been your experience? Is food blogging inherently hard? Is there a way to fit food blogging sustainably and easily into one’s life?

**

EMILY

EMILY

I don’t think food blogging is inherently hard—I have a much easier time of it than something like, say, fashion blogging, because I understand food but clothes remain a mystery to me. In most food blogging, food is the creative outlet—it’s a kind of art of its own, and so blogging about food is really just communicating a different form of expression, if that makes sense?

I think that people get satisfaction from different parts of it. I’m not a great photographer, so for me the staging and photographing is an afterthought, because no amount of effort in that regard is going to make my crappy iPhone photos significantly better; I think I’m a decent writer though, so I hope to coast on the quality of the writing and the recipes. For other people who are perhaps better photographers, maybe the writing feels hard.

In terms of accuracy and recipe development, that is a unique challenge but again I’d liken it to its own art form. Like, why would anyone do this if they weren’t either creating or archiving something? For me food blogging made sense—my education is in creative writing, but I am most excited about food, and we have to eat anyway. Food blogging became a way to write every day, or at least fairly often at a time when I might not have known what else to write about.

“Food blogging became a way to write every day, or at least fairly often at a time when I might not have known what else to write about.”

The challenge of sustainability now, I find, has less to do with the form and more to do with my own motivation. There’s a lot of “content” out there. I recognize that this is my own problem—food blogging is very different in 2016 than it was in 2008, and there are so many new voices that it can be hard to wade through and find your people. I won’t read on if I feel like a blogger is writing sponsored content, which is perhaps unfair, but again there is just so much out there now that I get to choose not to be marketed to if I don’t want that. At this stage, I am really looking for writers who make me look at food differently, or who use food as a vehicle for a larger story, whether there’s a recipe at the end or not.

**

KERRY

KERRY

So interesting. I am also really invested in the idea of blogging as a process, and a never-ending one too. An opportunity to learn and grow. That is why I started blogging about books back in 2007ish. Which is definitely at odds with the way that most bloggers these days are urged to position themselves as experts and gurus. I feel like we don’t get to see any of the process anymore, that the process is regarded as mess, something to be swept into the corners.

Did you have any food blogger “credentials” when you started blogging back in the day? Were they even necessary? You talk about motivation for food blogging—do you think people blogging in 2016 are blogging for blogging’s sake, or are they blogging with the intention of a book deal or some other professional opportunity? And I want to know also—what motivates you to keep blogging after all this time?

**

EMILY

EMILY

It’s totally a process! That’s why I don’t delete all my terrible, very bad posts with their clunky writing and hideous photos, because I like the idea that you can follow someone back through their process of growth. I remember when I first discovered The Bloggess in maybe 2009, and she was so funny and wonderful, and I had an evening alone (and no children), so I went all the way back through her archives and marveled at how her voice had strengthened and changed as she worked at it. There’s value in the process, and if nothing else it’s reassuring to be able to go back and see how you’ve evolved.

“I don’t delete all my terrible, very bad posts with their clunky writing and hideous photos, because I like the idea that you can follow someone back through their process of growth.”

I think the difference between then and now is really in how we’ve come to view online writing—the idea of “content” creates this sort of urgency to post regularly, to demonstrate value and expertise and keep people coming back. There has always been talk of “building an audience,” but prior to maybe 2011 the message was “make something valuable and people will come.” I don’t think that’s changed, but social media has really altered how that happens—now you don’t just have to make good blog posts, you also have to market them, and you—that was always kind of the case, but there’s so much more “content” out there now, that you have to put in a lot of effort—on a greater number of platforms—to stand out. If you want to do it well now, you have to think of yourself as a “brand” which honestly just feels so ridiculous. I get it, but I don’t want to do it.

“There has always been talk of ‘building an audience,’ but prior to maybe 2011 the message was ‘make something valuable and people will come.’ I don’t think that’s changed, but social media has really altered how that happens.”

Which is not to say that people who are doing it are doing blogging wrong, it’s just that the culture has changed. It does seem like people spring up fully formed overnight, with these beautiful sites and strong voices, but I wonder if part of that is that these are people who are approaching it with more online experience. When I started, I had had a Facebook account for maybe a year and that’s about it; I think now, for a lot of people, the social and visual aspects of blogging come pretty naturally. The technology is better—everyone has an iPhone now and iPhones take pretty good pictures. Getting to where you can be seen as an expert in whatever you’re doing is not such an investment as it used to be. “Anyone can do it” has turned into “anyone can do it well.”

I didn’t really have much in the way of credentials when I started, short of a writing degree. But is a writing degree any less a credential than professional cooking experience, if the blog’s audience is the home cook? The people who did really well early on had really strong perspectives—people like David Lebovitz, or Luisa Weiss, or Pim Techamuanvivit (who has since quit blogging). They really created the model for what you see a lot of people doing now, and I think created a sense of what you can do if you do well online.

I didn’t really have much in the way of credentials when I started, short of a writing degree. But is a writing degree any less a credential than professional cooking experience, if the blog’s audience is the home cook? The people who did really well early on had really strong perspectives—people like David Lebovitz, or Luisa Weiss, or Pim Techamuanvivit (who has since quit blogging). They really created the model for what you see a lot of people doing now, and I think created a sense of what you can do if you do well online.

Do people blog just to blog, or do they want something else, like a book deal? I don’t know. I think people sit down and open a WordPress account for the same reason they ever did—a desire to connect, to write, or just to find their people online. But I think there is more of a sense that if this goes well, there are other opportunities in it. People take bloggers more seriously now than they did even a few years ago. You certainly see a lot of blogger cookbooks now, and they are often quite well done (and do very well).

“I think people sit down and open a WordPress account for the same reason they ever did. But I think there is more of a sense that if this goes well, there are other opportunities in it.”

As for me and why I still do it? Well, I certainly do it a lot less than I used to, because now I feel like I only want to write when I have something to say, or a recipe that’s really worth sharing, or to gauge whether what I’m working on is something people want to see more of. With other social media, like Instagram or Facebook, I still feel very connected to my community, so I spend a lot of time on there and other platforms. I treat my site as more of a portfolio—I don’t get paid to write on my blog (I don’t do ads or sponsored posts), but it generates other opportunities. It also allows me to work out my point-of-view a bit, and to figure out what I want to do. I would not have had the opportunity to write the book without the blog; now that I’ve written the book though, the blog is still very important in that it’s a place to dabble and experiment with what I want to do next. It’s a very public way of working shit out for myself. I also get the benefit of feedback—people will make the recipes or comment on the writing, so I know pretty quickly what’s working and what’s not. It’s a hard thing to let go of, especially if you came up in writing workshops and are used to a more collaborative approach to the creative process.

This ended up being a lot of words! In short, I think that blogs are valuable and the evolution and messiness is valuable and we’re in a time of transition, because at this point blogs aren’t going away and also there are always more blogs. But like anything produced en masse, there’s good, meaningful stuff in there and I want to see it, especially if it’s a bit unrefined.

**

KERRY

KERRY

You are my blogging soul sister! That space to grow and evolve is so essential to successful blogging, I think (and I think a lot of bloggers who head into the gig thinking strategy and imagined outcomes are going to trip up on that). I am curious about your ideas about actually reading blogs. In my course, whenever I ask students what blogs they read, they usually shrug their shoulders and admit, “none!” Which is not to say that nobody reads blogs. I think that lots of people read blogs, but we come to them more laterally. I read food blogs all the time, but usually find them by googling whatever happens to be in my fridge and seeing what recipes result. I used to use a blog reader back in the day, but then Google ended it, and my blog reading was kind of rudderless after that—and I missed blogs. So I actively sought out a blog reader (I use protopage.com) which made reading blogs more of a regular habit. Kind of anachronistic, but I like it old school. I have a small but loyal group of readers who seem to feel just the same (and this is not JUST my mom). Anyway, I am interested in your thoughts on reading blogs and also finding readers. As you said, social media is a huge part of this.

Also, regarding the messiness: do you think it’s just too terrifying for some people to show their mess in public? Is that’s what’s driving the push toward tidy blogs? And by tidy, I mean antibacterial robot blogs? Is the blogger who’s willing to show her process taking risks that might be unwise?

**

EMILY

EMILY

Ha! I’m glad we’re on the same page, as I often feel like I am a cranky old man about everything and no one understands 😉

Google Reader did kill blog-reading for me, in a lot of ways—remember when you could follow, like, 50 blogs? 100 blogs?! Haha, no. I don’t read a huge number of bloggers, but I have kept up with the ones who tell good stories, or who make me laugh. I love Afroculinaria, and Eating From the Ground Up, and The Pizzle, food-related blogs that offer more than just content. The thing about “content” is it’s stuff meant to fill space. How much of what we’re putting out there is valuable? How much can any one person care about? I know content when I see it, and there’s a real difference between reading something someone put thought and time into and some junk they threw up just to have a post on Tuesdays as per usual, you know? And so, I am reading fewer and fewer blogs. But the ones I am reading, I’m really invested in. Like, I would be genuinely sad if they went away. But you’re right, I don’t think people “read” blogs in the same way that they used to—I agree, I definitely come to blogs more laterally now, and I don’t often click “follow” on the blog when I find someone I like—I find them on Instagram, or on Twitter or Facebook.

I also get to say all that as someone who has been around long enough to not really have to hustle for readers. Do I need more readers? I am sure in terms of marketing books more readers would be valuable, but I am not unhappy with how I am doing, and the amount of traffic moving through the site on a daily basis, even when I don’t post very often. I recognize that the landscape is different now, and I get to be someone with cobwebs and cat hair and it’s, like, my thing. Maybe it’s not that we’re not hustling, we’ve just earned the ability to not have to? Maybe those newbies with their neat presentations and good cameras and shiny websites look at people like us, who have been around a long ass time and don’t feel obligated to bother with Pinterest, with envy?

“Maybe it’s not that we’re not hustling, we’ve just earned the ability to not have to?”

It might be scarier now to show your mess in public. Mess isn’t marketable, and I think because there are so many blogs out there now, you need to look like you know what you are doing in order to be taken seriously, or at least to be followed by people who don’t care about stuff like messiness and the creative process (which I think is most people). Another aspect of this is that a lot of these blogs are or want to be businesses—and businesses run quite a lot differently than creative projects. I want to say this in a way that doesn’t make me sound like an asshole (because I don’t mean anything offensive by it), but there’s a difference between writers and people who like to write; I think writers, or people who have always written (in the writers-as-artists sense), may value the mess and the show-of-process more than people who like to write but have other ambitions for their blogs. Writers aren’t penalized for having written shitty first drafts (or having evolved through a period of shitty-first-draftyness) because it’s expected, that’s what we do. But bloggers who want to turn blogging into something else, something beyond cookbooks or novels or whatever, maybe they approach it differently, and are more thoughtful about how they present themselves.