February 6, 2011

Sides of Peterborough, and Peterborough books

Michelle Berry’s “What It’s Like Living Here” got me thinking about my hometown of Peterborough a few weeks back, not least because she appears to live on the block where my two best friends grew up (and therefore me alongside them). Her piece awakened nostalgia for the Peterborough I left behind, while Candace Shaw’s response to it “I guess I do like it here” introduced me to a Peterborough I hardly know, and I think these both complement one another wonderfully.

Michelle Berry’s “What It’s Like Living Here” got me thinking about my hometown of Peterborough a few weeks back, not least because she appears to live on the block where my two best friends grew up (and therefore me alongside them). Her piece awakened nostalgia for the Peterborough I left behind, while Candace Shaw’s response to it “I guess I do like it here” introduced me to a Peterborough I hardly know, and I think these both complement one another wonderfully.

I’m thinking about Peterborough at the moment now, however, because I had brunch with my friend Mike this morning, and also because I’m rereading Sarah Selecky’s collection This Cake is for the Party. Selecky is a Trent grad, and many of her stories take place along the city’s hallowed routes (sirens on Water Street). Andrew Pyper’s Kiss Me also contains stories set in Peterborough. And Paul Nicholas Mason’s novel Battered Soles is THE Peterborough novel, as far as I know– I enjoyed it very much a couple of years back. Any other Peterborough stories I’m missing?

Because as far as I’m concerned, no place is real until it has been rendered as fiction.

January 18, 2011

The Torontonians by Phyllis Brett Young (and Betty Draper)

Phyllis Brett Young’s 1960book The Torontonians is not necessarily to be read as a stunning example of the novel form. The satire and irony have been rendered most unsubtle in the years since its first publication, so that The Torontonians reads more like Cyra McFadden’s The Serial than a remarkable work of literature. Remarkable, however, The Torontonians most certainly is when it is read for its feminist content and Toronto setting. It’s a fun read too, and in places very funny.

Phyllis Brett Young’s 1960book The Torontonians is not necessarily to be read as a stunning example of the novel form. The satire and irony have been rendered most unsubtle in the years since its first publication, so that The Torontonians reads more like Cyra McFadden’s The Serial than a remarkable work of literature. Remarkable, however, The Torontonians most certainly is when it is read for its feminist content and Toronto setting. It’s a fun read too, and in places very funny.

Published three years before Betty Friedan’s book, The Torontonians is The Feminine Mystique put to fiction, except that Young makes clear what most modern readers of The Feminine Mystique miss: the new woman problem is not so much with the domestic sphere itself, but rather with what consumerism has done to it. Women have never had it so good, except that their labour has been alienated from production via labour saving devices, which don’t actually save labour but just create more jobs to do. And then they’re expected to be fulfilled by the material goods that decorate their houses, and adorn their yards, and when they fail to be, nobody can imagine what could possibly have gone wrong. In its critique of consumer society, Young’s novel anticipates Atwood’s The Edible Woman.

The Torontonians also employs that setting so familiar from Atwood: the city of Toronto. London’s creeping here too, as Karen Whitney’s home on the city’s outskirts overnight becomes the centre of suburban Rowanwood (which was modelled on Leaside). One of the most enduring images of the novel is the Whitney’s buckweed lawn, which they’re forced to spend a summer painstakingly installing because they can’t afford to lay down sod but also realize their neighbours are running out of patience with their uncultivated grass. Rowanwood is the kind of neighbourhood in which a house with just one bathroom is frowned upon for dragging down the market value of the others.

In her novel, Young paints a picture of Toronto in the midst of transition, juxtaposing the suburbs against downtown where Karen had grown up in the Annex neighbourhood. She writes of a Toronto elite (“the Masseys and the masses”) who were all familiar through family connections, and attended the same private schools. But the city, howeer constant in its hum, is always changing. With some of her scenes set against pre-CN Tower aerial views, she shows that no one ever steps into the same city twice.

Young’s novel is a historical document, and deliberately so, as as the book’s introduction makes clear. She thought it was important that  writers document the way people lived then, and so we get a story in which doctor and patient both smoke during an examination at the Medical Arts Building at Bloor and St. George. We read about a city in which the subway was new, New Canadians were usually Hungarian, downtown high rise apartments were novel (and an exotic dream for the bored housewives of Rowanwood). There is the Peyton Place-ish suburban sex too, and a very funny line about who’d do what in Loblaws, but Young shows restraint here. By the end of the book it is quite clear that her people are not caricatures, and the narrative rises above plot cliches.

writers document the way people lived then, and so we get a story in which doctor and patient both smoke during an examination at the Medical Arts Building at Bloor and St. George. We read about a city in which the subway was new, New Canadians were usually Hungarian, downtown high rise apartments were novel (and an exotic dream for the bored housewives of Rowanwood). There is the Peyton Place-ish suburban sex too, and a very funny line about who’d do what in Loblaws, but Young shows restraint here. By the end of the book it is quite clear that her people are not caricatures, and the narrative rises above plot cliches.

(The Torontonians is also very, very Betty Draper, and is the first Mad Men-ish book of a few I will be reading in the next while. The others are The Collected Works of John Cheever, and Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything. Any other suggestions?)

December 31, 2010

Happy New Year

In every way, it’s been a pretty wonderful year. We began it still pretty shell shocked from the chaos that having a baby created, but it was also when I really began to enjoy the shape of our new life with Harriet, and the pace of our every day lives together started improving in leaps and bounds. Harriet has become more fabulous with every passing month, and these days we never threaten to throw her out the window more than once or twice a week. I also continue to adore her dad a whole lot, and note that he is pretty much the key to everything good.

In every way, it’s been a pretty wonderful year. We began it still pretty shell shocked from the chaos that having a baby created, but it was also when I really began to enjoy the shape of our new life with Harriet, and the pace of our every day lives together started improving in leaps and bounds. Harriet has become more fabulous with every passing month, and these days we never threaten to throw her out the window more than once or twice a week. I also continue to adore her dad a whole lot, and note that he is pretty much the key to everything good.

Other keys to everything have been joining a local writers’ salon with a wonderful group of women who are extraordinary in both talent and generosity of spirit. Our meetings have been a source of great company, conversation, ideas, inspiration, and friends. Concurrently, I have also been honoured to be a member of The Vicious Circle book club, and meetings have been along similar lines (albeit a bit more ribald in tone). Both have been the very best ways to spend my time-off from motherhood, and I look forward to them always. I also mark how far I’ve become this past year by remembering my first salon meeting in February, how I’d never left Harriet in the evening before, but how we all made it (including Stuart, who was tasked with putting her to bed solo), and how me leaving the house at night is no longer remotely a big deal.

I have been extraordinarily blessed by creative opportunities this year. I’ve had two stories published, and had a dream come true as reading as part of Eden Mills Festival Fringe Stage. I’ve written lots of book reviews, and published two essays on topics I care about deeply (and then there was the matter of that shout-out by the Utne Reader). None of this was on the cards one year ago, and so it leaves me hopeful for what 2011 will bring (though I looking forward to seeing my piece in the Sharon Butala Special Issue of Prairie Fire this Fall, which has been forthcoming for about two years now).

My goals this year are to finish the first draft of my novel, to finally read Great Expectations, and to not drive our rental car into anything when we go to England in March. I am going to try to get out to more literary events, although not too hard because there is really no better place to be than my house. I am excited to be teaching The Art and Business of Blogging at the UofT School of Continuing Studies in April. And I look forward to finding new and creative ways to live frugally in the city, while concurrently exploiting the many opportunities that city-living brings.

I have read 149 books this year, which I’m pretty pleased with, mostly because so many of them have been wonderful. For this large total, however, I really only do have Harriet to thank, and her wonderfully epic nap times. Long may they live. It has been a diverse list of books read, male and female authors, a bit too heavy on the contemporary due to judging a book prize this summer, but otherwise I can’t see any major gaps. It’s worth nothing, however, just how much satisfaction I am getting from independent Canadian Presses even as I’ve become a more more demanding reader these last few years, and it was so exciting to see them get their due through the Giller long and shortlists this year. May indie presses outlive even Harriet’s naps (or they could both live on forever?).

And may 2011 be full of good things.

December 14, 2010

Knowledge had to be fought for

“All this affected my formation as a historian: I became addicted to the thrill of the chase, the excitement of the game of matching your wits and will against that of Soviet officialdom. How boring it must be, I thought, to work on British history, where you just went to the PRO, and polite, helpful people gave you catalogues and then brought you the documents you wanted. What would be the fun of it? Knowledge, I decided, had to be fought for, achieved by ingenuity and persistence, even – like pleasure, in Marvell’s words – snatched ‘through the iron gates of life’.” –Sheila Fitzpatrick, A Spy in the Archives (full text available!).

October 8, 2010

The world in fiction

Last night I was part of a discussion with a group of women whose collective brilliance could light up the universe, and we were talking about using the real world in our writing, fiction or non-fiction. (We were also drinking champagne, eating cake, and delicious cheese, but that is another story.) Everybody had such fascinating input, about the ethics of using other people’s stories, about writing historical fiction or speculative fiction, and using the details but not conspicuously. About writing memoir, and something about fiction being the truth told twice. And then someone brought up Carol Shields’ Small Ceremonies, which was so perfect, being about this very topic, and also because for about two days, I’ve been dying for somebody to talk about Small Ceremonies with.

Anyway, I thought about the one story I’d ever done substantial research for, which was set in 1976 when the CN Tower first opened. I have long been fascinated by my impression of the CN Tower as a permanent fixture on the horizon, as old as the universe, or at least as old as the TD Tower, but then to realize that it’s only three years older than I am (but then, don’t we all envision ourselves too as well as permanent fixtures on some horizon, old as the universe?). That, not entirely literally, Torontonians went to bed one morning and woke up to a tower in the sky.

So that was what my story was about, and I spoke to people who remembered the tower’s construction, and read a 1970s’ Toronto guidebook, and read every archived newspaper article I could find on the subject. I went through the CHUM charts to find out what was playing on the radio (an aside: these were all available online until about two years ago, when CHUM was bought by CTV). I read Toronto fiction from that time, and spent a lot of time thinking about the view from our friends’ high rise apartment at Yonge and St. Clair. We were also so poor at this point in time that a research trip up the tower itself required budgeting for weeks, but we did it on one cold February day in 2006. I’d brought a falling apart book about Toronto from the library so we could compare the views.

Geographic or historical detail, as someone noted last night, can function as a scaffold. We seemed to also conclude that broad strokes work best in convincing historical fiction, and it reminded of what Alison Pick said in our interview: that the essential goal of historical fiction is that its details be grounded in time and place, but the feel and its characters be entirely contemporary. That a scaffold has to come down once the building is completed. That a writer has to ground herself in the details of time and place, and then forget it in order to get the story written. That the detail of where a story takes place, or what is playing on the car radio, or what kind of car it is– that none of this is important, unless it functions in the story at a deeper, symbolic or metaphoric level. And in terms of place, I thought of how Claudia Dey did this so well with Parkdale in Stunt, and Elise Moser with Montreal in Because I Have Loved and Hidden It. The broad strokes with which Hilary Mantel evoked the Tudors inWolf Hall. How with the best novels we’ve read in our book club (Shirley Jackson, Muriel Spark), we’ve remarked that these stories are ageless, could have taken place in any time. And perhaps a similar spirit needs to be striven for in historical fiction too, in any fiction. Spirit can’t come from detail for the sake of detail– everything has to mean something. That the song on the car radio is a kind of cheating, and it shows.

My CN Tower story was a mess, a catalogue of facts and coordinates. I haven’t tried to set anything in the past since, but I’m thinking about it now, as a kind of challenge. A detail-less historical short story– I wonder. And I will keep in mind a point somebody made last night– that people themselves are the centre of our stories, and people themselves don’t change that much. Reflecting this morning upon this, I remembered how my CN Tower view was nearly identical to the pictures in my battered book. Perhaps this means something more than itself, and I’ll try to keep it in mind.

September 28, 2010

When Fenelon Falls

I wrote about my adventures this summer in the land of (almost) no bookshops, and had determined that this area of the Kawartha Lakes region was about as unliterary as they come. And then, this Sunday at the Word on the Street Festival, I discover hot off the Coach House Presses is When Fenelon Falls by Dorothy Ellen Palmer– somehow this unliterary land has generated a book of its own. Having spent about fifteen childhood summers in the vicinity, in addition to a week in August, this book is now a must-read, and though Palmer’s story takes place long before I came along, I am sure some bits will still be quite familiar.

August 25, 2010

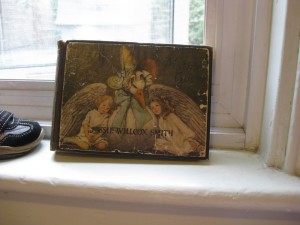

Notables: The Little Mother Goose

Though I collect books, I am by no means a Book Collector, because most of my books are battered paperbacks that Penguin put out in the ’70s. I do, however, have some notable exceptions in my library, which are by no means valuable or rare, but they still possess a certain kind of charm. And so these books will be the subject of a new Pickle Me This feature, which I have just entitled Notables.

Though I collect books, I am by no means a Book Collector, because most of my books are battered paperbacks that Penguin put out in the ’70s. I do, however, have some notable exceptions in my library, which are by no means valuable or rare, but they still possess a certain kind of charm. And so these books will be the subject of a new Pickle Me This feature, which I have just entitled Notables.

The first notable is The Little Mother Goose by Jessie Wilcox Smith, and the first cool thing about this book is that it’s available in its entirety as a Project Gutenbergy eBook, whose pictures are sharper than those in my book, which is points for digitization. My book doesn’t have hyperlinks either.

My book, however, unlike the digital version, is almost ninety years old, and is inscribed (in ink that hasn’t even faded), “To Helen on her fifth birthday. from Mama.” Helen is my late-grandmother, and her mother died when she was eight years old. My mother, who is Helen’s daughter, had the book rebound, and gave it to me for Christmas two years ago when I was pregnant with Harriet.

(The power of book as object [or I suppose the power of object in general, of relic] is underlined by what I find in my great-grandmother’s letters, which I have a collection of. On a whim, I just opened it to April 16, 1923, and found this: “My dear Susie, This is Helen’s birthday and she had quite a glorious time. She started kindergarten last week but I didn’t let her go today as she had quite a cold and I thoguht maybe she was developing measles…/ Your brass jardinier came long ago. She is very fond of it and spent about a half hour polishing it today. Other gifts she received were- A pair of gloves from Daddy/ A Child’s Garden of Verses by Stevenson from Clara…/ Skipping rope from James/ The Little Mother Goose illustrated by Jessie Wilcox Smith from Mama and a hankie from little Hazel Keenan who was here for tea. I made a lovely angel cake and of course it had candles, Mother brought ice cream for a treat too. So the child had quite an exciting day altogether.”

Indeed, as Tom Stoppard wrote in Arcadia, “We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind…” Though I wonder what happened to the hankie or the jardinier. I imagine the cake was devoured…)

Anyway, I’m way off track. In addition to its beautiful illustrations, this book is full of nursery rhymes you’ve never ever heard of, and the proportional few that you have.

Like, “Pickeleem, pickleem, pummis-stone! What is the news, my beautiful one? My pet doll-baby, Frances Maria, Suddenly fainted and fell in the fire; The clock on the mantle gave the alarm,/ But all we could save was one china arm.” And that little-known second verse to Jack and Jill: “Up Jack got and home did trot, As fast as he could caper; Dame Jill had the job to plaster his knob, With vinegar and brown paper.” Um, yes.

A few rhymes referencing something called “Chop a nose day.”

And many riddles, including “A riddle, a riddle, I suppose. A hundred eyes and never a nose.” (Answer: a cinder-sifter). I probably wouldn’t have got that one.

July 18, 2010

Rereading Still Life With Woodpecker by Tom Robbins

I’ll start with the fact that makes me want to die the least (honestly): I used to claim that all the wonderment of literature in general was contained within this one book, and if it was the only book left on earth, all the best things about literature would still remain. I am very glad I never was made to prove this.

I’ll start with the fact that makes me want to die the least (honestly): I used to claim that all the wonderment of literature in general was contained within this one book, and if it was the only book left on earth, all the best things about literature would still remain. I am very glad I never was made to prove this.

And then that I used to have a framed pack of Camel cigarettes hanging on my wall. I believed that it contained all the secrets of the universe, and would inspire me to be the kind of person I wanted to be.

That my copy of this book bears a heartfelt message from a boy who says he loves me. Which is really sweet, unless you know that I encountered him in an internet chatroom one day when I was very bored in 1999, and that we never met. (Though we did used to have discussions about how to make love stay, both agreeing ardently that when the mystery of the connection goes, love goes. However, we never did address how exactly the mystery of connection applies to two people who’ve never met.)

I think I’m less embarrassed about all that, however, than I am about the numerous lines throughout the text that I underlined in purple ink, in particular, “Me? I stand for uncertainty, insecurity, surprise, disorder, unlawfulness, bad taste, fun and things that go boom in the night.” Seriously, why did that speak to me? Because I only ever underlined things in purple ink if they resonated with my deepest being, but no one has ever stood for those things less than I do. Except bad taste. I think maybe it was aspirational…

So there are many ways to begin explaining just how much rereading Still Life With Woodpecker was an exercise in embarrassment. (And I reread this as part of Mark Sampson’s Retro Reading Challenge, I’ll have you know, of which embarrassment was sort of the point, but still, this must be unprecedented) I will explain that when I encountered this book, I was twenty years old and very bored, and that I was just contemplating turning my world upside down for the very first time. (The other line I fervently underlined during this period was from Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia [which I still love] which is: “This is the best time possible to be alive. When everything you know is wrong”).

Still Life… is the story of Leigh-Cheri, an exiled princess/all-American girl (like Anne Hathaway, but with more of a tendency toward unwanted pregnancies) who falls in love with a terrorist (and this was back when terrorism was still homey, domestic and romantic). Bernard is an “outlaw”, outside the law in every sense, except that he gets thrown back in jail, the couple drifts apart, her Arab fiance builds her a pyramid, the couple is reunited, and owe everything to a stick of dynamite. Bernard teaches Leigh-Cheri how to really be free, that love is crazy barking at the moon, that the moon is everything (including birth control), that sometimes you’ve got to throw caution to the wind, and blow a bunch of shit up.

When I read this book the first time, it gave me license to imagine I could live the kind of life I’d imagined. It made me feel more confident about going boldly forth, and making mistakes, and blowing shit up, and breaking the rules, and though I never did any of these things terribly prolifically (apart from the second), I am glad I learned these lessons when I was twenty years old. My life could possibly have been different otherwise, but I am not so sure I owe it as much to the Camel pack as I thought I did.

Rereading this book at 31, I see how far I’ve come, and how my literary judgement has sharpened, because the book is terrible. My political judgement has sharpened also– the Woodpecker is an anti-feminist, libertarian, but I would have noticed neither of these details then. Robbins’ prose is an orgy of play, but his language means nothing beyond its frippery, and it’s not even that funny– the only time I laughed out loud was when somebody sat on a chihuahua. I was bored reading most of it, and so bored out of my head by the end that I was only skimming. The sex was awful and gross, and not remotely sexy. The vagina euphemisms were totally disgusting, and I’m not sure why that didn’t put me off first time through.

I’m glad I reread it though– there were sparks of how brilliant I used to think it was. I don’t know if I’d ever read anything that interesting before, and it might have liberated me as a reader in the same way it did in a more general sense. And I wasn’t wholly cynical about its message. Even now, the idea of having CHOICE guide one’s life is very important to me: “To refuse to passively accept what we’ve been handed by nature or society, but to choose for ourselves. CHOICE. That’s the difference between emptiness and substance, between a life actually lived and a wimpy shadow cast on an office wall.” Rock on Tom!

Kind of inspiring, but not quite worth the 252 pages it took to get there.

July 11, 2010

Rereading Slouching Towards Bethlehem for the fifth time

Rereading Slouching Towards Bethlehem for the fifth time, and it’s full of moments. First, my own moments– cracking the book open for the first time six years ago on a tram enroute to Miyajima, reading it again in 2008 after having been to California, that same rereading and the line from “On Keeping a Notebook”, “because I wanted a baby and did not then have one”, and rereading it again with the baby asleep in her room. It is like keeping a notebook, all the secrets this book holds about who I used to be, and it’s a different journey every time.

Rereading Slouching Towards Bethlehem for the fifth time, and it’s full of moments. First, my own moments– cracking the book open for the first time six years ago on a tram enroute to Miyajima, reading it again in 2008 after having been to California, that same rereading and the line from “On Keeping a Notebook”, “because I wanted a baby and did not then have one”, and rereading it again with the baby asleep in her room. It is like keeping a notebook, all the secrets this book holds about who I used to be, and it’s a different journey every time.

It’s curious that this is a book I can’t stop reading, a book that I long for when we’re parted too long. Because I like novels so very much, but this book of essays speaks to me in a way few novels ever have. Lucille Maxwell Miller and her volkswagen, and the fact of a man called Arthwell Hayton (who went on to marry the au pair, of course). The title essay, and a derailed social movement that Didion puts down to inarticulacy. The way she writes, the repitition and the cadences– her prose is music. Hypnotic. She describes “people of character”, which is a term we hear even less than when she hardly ever heard it anymore. “You see I want to be quite obstinate about insisting that we have no way of knowing– beyond that fundamental loyalty to the social code– what is “right” and what is “wrong”, what is “good” and what is “evil””– which underlines everything she writes, how she appears to just let the pieces fall where they may, her facts and stories speak for themselves, and they do. She’s the most uninstrusive omniscient narrator I’ve ever encountered.

And oh, she’s cool. Her California (you should read her memoir Where I Was From), and her Hawaii, where she is sent to in this book not in lieu of a divorce, but because she was a “recalcitrant thirty-one-year-old child” (as am I!). How she cried in Chinese laundries, and her golden curtains flew out the window and got drenched in the rain, and how the maid sulks when the wind blows (doesn’t she just?). The helicopter dropping the morning paper off on Alcatraz, and how she went to the grocery store in her bikini. And she spins and she spins and she spins– what a master.

I remember reading this book for the first time, and how it was nothing like what I had thought it would be, and how it was harder. To follow the circles of her arguments, to grasp the ungraspable (that things fall apart, the centre cannot hold). I remember how every time I read this book, I discover something new, and how it’s always summer. (“I imagine, in other words, that the notebook is about other people. But of course it is not.”)

July 8, 2010

I wish my enemies were Russian

(I wrote this poem a few years ago, back when I wrote poems, and I’m reposting it now, in light of recent events, to celebrate my wish coming true.)

I wish my enemies were Russians

for the privilege of your naivete

they played you like an instrument

set against that Europe

your Russia was a love story;

the thinking man’s erotic fantasy.

You wrote odes to odes on lunacy

but even the polarity was an illusion

shifty spies confused the confusion.

That war was all in your head;

endless scenes of winter

intrigue. Your house with

picture windows and a fallout shelter;

mutually assured destruction.

Your history was the cinematic stuff

of fiction. The enemies were Russians

with beady eyes and edgy names.

Your symbols were comic book

red menaces and red phones,

iron curtains and star wars.