October 25, 2012

My Grade 12 English Text

I’ve started reading Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories, because mention of it keeps turning up here and there, and because I keep spying it on terribly clever people’s bookshelves. I got a used copy last weekend, and opened it for the first time this morning to start reading “Celia Behind Me”: “There was a little girl with large smooth cheeks who lived up the street when I was in public school.” And I realized that I’d read this story before, more than once. It was so strangely familiar, like something I’d known in a dream, but somebody else’s dream. So distant because I’d read it a long time ago.

I’ve started reading Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories, because mention of it keeps turning up here and there, and because I keep spying it on terribly clever people’s bookshelves. I got a used copy last weekend, and opened it for the first time this morning to start reading “Celia Behind Me”: “There was a little girl with large smooth cheeks who lived up the street when I was in public school.” And I realized that I’d read this story before, more than once. It was so strangely familiar, like something I’d known in a dream, but somebody else’s dream. So distant because I’d read it a long time ago.

A little investigation revealed that I’d read the story in The New Oxford Book of Canadian Short Stories, edited by Margaret Atwood and Robert Weaver. I remembered the text, a row of spines lined up on the shelf in my grade 12 English classroom. I’d remembered “Celia Behind Me,” and also a story called “White Shoulders” (I remember being perplexed by it) which I was surprised to find out was by Linda Svendsen. (Alice Munro’s “The Red Dress” was not in the collection, but I remember reading that story too in the class.)

I was most surprised to discover that right there in my high school text were all these writers who I feel as though I’ve discovered in the last few years and who’ve become really important to me– Bronwen Wallace, Caroline Adderson, Cynthia Flood. And that Leon Rooke was there too, and John Metcalf, Clark Blaise, Diane Schoemperlen, Barbara Gowdy, Douglas Glover, Thomas King. I am pretty sure that we didn’t read “We So Seldom Look on Love” in my grade 12 English class, but I am just as sure that if I encountered many of these stories again, they would seem as instantly familiar as “Celia Behind Me” did.

This re-encounter has given me a new appreciate for the hoopla surrounding the Salon de Refuses and the Penguin Book of Canadian Short Stories in 2008. Well-curated anthologies are the optimum way for students to discover the short story, each one onto itself, one at a time. These seminal texts are also more important and influential than I’d before supposed, definitely sowing the seeds of love for short stories and for (Canadian) literature.

For me, it would take awhile for the love to bloom. I would not be exposed to contemporary writing this good again for years, and years, and I’d have to seek it out for myself. But maybe I hadn’t been on my own entirely. It’s been a meandering path from from there to here, but I am pretty sure that the me who picked up Isabel Huggan this morning (for fun) has The New Oxford Book of Canadian Short Stories to thank for a lot of the journey.

September 11, 2012

The Comics

It’s true that from a very young age, I read the entire Saturday paper cover-to-cover, if by “the entire Saturday paper” you mean the Toronto Star comics supplement in all its glorious colour. I loved Blondie and Beetle Bailey, Family Circus and For Better or For Worse, The Better Half and Spiderman. I liked Broom Hilda, Dennis the Menace, Hi & Lois, and Hagar the Horrible, though I was confused by Little Orphan Annie because it wasn’t like the movie at all. I was depressed by Jon Arbuckle and Cathy, but read their strips anyway, and all the others I didn’t really understand– Ernie, and Mother Goose and Grimm, Shoe, and many others. In fact, it’s likely that I didn’t understand any of the comics, really, but it didn’t stop me from poring over them every Saturday morning, lying on the living room carpet in my pajamas. There was something in their colours and cartoonishness that made clear that this was my part of the paper; the comics were an invitation and an introduction to the pleasures of newspaper reading.

It’s true that from a very young age, I read the entire Saturday paper cover-to-cover, if by “the entire Saturday paper” you mean the Toronto Star comics supplement in all its glorious colour. I loved Blondie and Beetle Bailey, Family Circus and For Better or For Worse, The Better Half and Spiderman. I liked Broom Hilda, Dennis the Menace, Hi & Lois, and Hagar the Horrible, though I was confused by Little Orphan Annie because it wasn’t like the movie at all. I was depressed by Jon Arbuckle and Cathy, but read their strips anyway, and all the others I didn’t really understand– Ernie, and Mother Goose and Grimm, Shoe, and many others. In fact, it’s likely that I didn’t understand any of the comics, really, but it didn’t stop me from poring over them every Saturday morning, lying on the living room carpet in my pajamas. There was something in their colours and cartoonishness that made clear that this was my part of the paper; the comics were an invitation and an introduction to the pleasures of newspaper reading.

I do love newspapers, inky ones. When we lived in England, we used to buy so many weekend papers that getting them read was our chief occupation. And these days, we subscribe to the ever-shrinking Saturday Globe & Mail, and it’s still one of my favourite parts of Saturday morning, Tabatha Southey, tea, book reviews and croissants.

Lately Harriet’s got her own part of the paper, and she starts shouting for it as soon as I bring the paper in: “Comics! Comics!” Which is kind of funny because The Globe & Mail comics are mostly terrible, but Harriet doesn’t know and doesn’t care. She sees the cartoon pictures, and she thinks they’re for her. And so she makes us read the whole section aloud, some comics over and over. I don’t know if there has ever been a family so intent on Drabble. Sometimes the comics are even less terrible then you’d think, and when that happens, we’re always kind of amazed.

And thankfully, when the comics are too unfunny, we supplement Harriet’s hunger for them with regular trips to our local kids’ comics shop.

February 29, 2012

Bookends: Joan Didion's Blue Nights and "On Keeping a Notebook"

As I read Joan Didion’s 1966 “On Keeping a Notebook” today, it occurred to me that this essay is the piece that is the bookend to her new book Blue Nights, and not The Year of Magical Thinking as so many critics have suggested. (I also don’t understand why no one talks about Where I Was From. I think it’s my favourite book of all of hers.)

As I read Joan Didion’s 1966 “On Keeping a Notebook” today, it occurred to me that this essay is the piece that is the bookend to her new book Blue Nights, and not The Year of Magical Thinking as so many critics have suggested. (I also don’t understand why no one talks about Where I Was From. I think it’s my favourite book of all of hers.)

But first, Blue Nights is not a book about Didion’s daughter Quintana Roo. So many readers have got that wrong too. As Didion writes in “On Keeping a Notebook”, “however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of what we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I’.” Like everything Didion has ever written, Blue Nights is profoundly about herself. She’s not even opaque about it, but some readers are still so unable to get around the fact of a woman writing honestly about motherhood than they’ve been hypnotized into thinking motherhood is all that Blue Nights is about.

But yes, to read “On Keeping a Notebook” after Blue Nights is to invest the essay with a whole new level of meaning. “Although I have felt compelled to write things down since I was five years old, I doubt that my daughter ever will, for she is a singular blessed and accepting child, delighted with life exactly as life presents itself to her, unafraid to go to sleep and unafraid to wake up.” And then later, “…I have always had trouble distinguishing between what happened and what might have happened, but I remain unconvinced that the distinction, for my purposes, matters.” In Blue Nights, Didion writes, “How could I have missed what was so clearly there to be seen?”

And then further on the essay when she addresses her notes, her compulsion to maintain these notebooks in order to keep in touch with the people she used to be, “paid passage back to the world out there”. She was 32 when she wrote this essay, which is the age I am now, and it’s an age at which you feel there are whole lifetimes behind you, and it’s so fascinating to consider these. 32 is an age where your preceding decade has changed life beyond all recognition, and you’ve finally sensed an order to it all. How, as the older woman in Didion’s essay tells her, “Someday it all comes.” And none of it has started to leave you yet; the future is all promise, and it’s here.

Blue Nights is a 77 year old Didion looking back at her 32 year old self who’d supposed herself older than she’d ever be again. In Blue Nights, she notes the boxes and drawers in her apartment stuffed with history, the notebooks, the stuff she’s been acquiring through her years, all items she’d once blithely advertised as “paid passage back to the world out there.”

She writes, “In fact I no longer value this kind of memento./ I no longer want reminders of what was, what got broken, what got lost, what got wasted./ There was a period… when I thought I did./ A period during which I believed that I could keep people fully present, keep things with me, by preserving their mementos, their “things”, their totems.”

She writes, “In theory these mementos serve to bring back the moment./ In fact they serve only to make clear how inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here.”

“It all comes back,” Didion writes in 1966, unaware of the shallowness of what she’d lost so far, convinced by the rhythm of her words. And Blue Nights is her realization more than 40 years later: there comes a day when it doesn’t anymore.

November 17, 2011

Of Eatons and Avenues

Last night I finished Rod McQueen’s The Eaton’s: The Rise and Fall of Canada’s Royal Family, which I was reading because Jonathan Bennett had included in his Power & Politics Book List, and then I found a copy in a cardboard box outside a house on Borden Street last summer. And to be reading this book right after Heather Jessup’s The Lightning Field is to be steeped in old Toronto now, to be rumbling up and down its avenues like the old cream coloured streetcars of my childhood. And to be so steeped is to be led down strange avenues online, pursuing the odd history of Dundas Street, or even leaving town to find this fascinating 1958 article in Macleans by Peter C. Newman about Deep River ON: “The Utopian town where our atomic scientists live and play has no crime, no slums, no unemployment and few mothers-in-law. But maybe you wouldn’t like it after all. Here’s why.”

Last night I finished Rod McQueen’s The Eaton’s: The Rise and Fall of Canada’s Royal Family, which I was reading because Jonathan Bennett had included in his Power & Politics Book List, and then I found a copy in a cardboard box outside a house on Borden Street last summer. And to be reading this book right after Heather Jessup’s The Lightning Field is to be steeped in old Toronto now, to be rumbling up and down its avenues like the old cream coloured streetcars of my childhood. And to be so steeped is to be led down strange avenues online, pursuing the odd history of Dundas Street, or even leaving town to find this fascinating 1958 article in Macleans by Peter C. Newman about Deep River ON: “The Utopian town where our atomic scientists live and play has no crime, no slums, no unemployment and few mothers-in-law. But maybe you wouldn’t like it after all. Here’s why.”

McQueen’s story of the Eaton family was readably rife with scandal and gossip, and good old fashioned story. Art heists, a foiled kidnapping, cuckolds, Fascists, terrorists, Rolls Royces, idiots, feuding siblings, and fallen empires– you wouldn’t know this was Canada. How the Eatons myth was divorced from its reality, and the public was so determined to keep the myth perpetuated. The book ends in 1997, when how far the Eatons would fall was still not entirely clear, and that they only fell further doesn’t undermine the story’s importance. That this book is out of print, however, to be found in curbside cardboard boxes only (though thank heaven for such distribution really) is totally ridiculous.

November 14, 2011

This is where we used to live.

2001/2002 was my final year at university, the year I had a back page column in the school newspaper and therefore had a platform from which to address the question of what it meant to live on a “grimy, yet potentially hip strip of Dundas St. West”, as my block had been described by the Toronto Star in a restaurant review of Musa. To live on such a strip meant kisses in doorways, I wrote, because no boy would ever let you walk home alone, it meant watching from your bedroom window as a dog devoured a skunk, and having to call the police when people started smashing car windows with implements from the community garden. I can’t remember what else I wrote in that piece, and Musa burned down two summers ago, but neither point means that year is lost. I have never gotten over it.

2001/2002 was my final year at university, the year I had a back page column in the school newspaper and therefore had a platform from which to address the question of what it meant to live on a “grimy, yet potentially hip strip of Dundas St. West”, as my block had been described by the Toronto Star in a restaurant review of Musa. To live on such a strip meant kisses in doorways, I wrote, because no boy would ever let you walk home alone, it meant watching from your bedroom window as a dog devoured a skunk, and having to call the police when people started smashing car windows with implements from the community garden. I can’t remember what else I wrote in that piece, and Musa burned down two summers ago, but neither point means that year is lost. I have never gotten over it.

Everything felt monumental that year, not because of anything specific, although it was our final year of school, and 9/11 occurred days into it, serving to make us think a lot about things we’d always before taken for granted. “That was a year,” wrote my friend Kate in a recent email, “we all made enormous leaps into adulthood even if many days it felt like we were just playing.” And of course, everybody has had those years, monumental if only for how they delivered us to here. A threshold to something finally real, but we were aware of it happening all the time, and so amazed to watch the world opening up before our eyes.

And so it felt entirely appropriate when I discovered last week that they’d turned our entire apartment into an art exhibition. (It all feels a bit Tracey Emin.) “They” being the people at Made Toronto, which now lives downstairs from where we used to live, though that storefront was a Chinese herb shop when it was ours. (It was a different time. We’d never heard of hipsters, and Musa was the only place to get brunch for blocks and blocks. David Miller wasn’t even the mayor then, and Spacing Magazine had yet to be invented.) The exhibition took place last year, designer furniture and housewares on display in a “typical Toronto apartment,” which is funny because there was nothing typical about it– for about nine months that I know of, that apartment was the centre of the universe. It’s also funny because it’s the ugliest apartment I have ever, ever seen. Aesthetically speaking (although “aesthetic” was not, in fact, a word I was aware of when I lived there), that apartment’s sole redeeming feature was the patio where I used to go to pretend to smoke cigarettes, and watch the city skyline.

Part of the reason I love my husband is because I brought him home for a visit from England in 2003 when the apartment was still inhabited by friends of mine. And they had a party to welcome me back, and so for two days, he got to know almost exactly what I was talking about when I talked about that place, about that time. I love that he was there, that brief intersection between my new life and my old one. I love that my roommates are still such dear friends, no matter that we live so far apart now. And I love that the hideous pink linoleum floors are just the same, and that we’ve come so far, they’re considered art now.

October 26, 2011

On re-watching Reality Bites

I was a deeply impressionable 14 years old when I first saw Reality Bites, and it came to define “cool” for the remainder of my teenage years and beyond: smoking, vintage dresses, ’70s nostalgia, passionate friendship, complicated relationships, the attractiveness of moody boys, and an obsession with self-obsession (“I’m making a documentary about my friends”). It taught us all to define irony so we wouldn’t be caught on the spot, it was David Spade at his finest (“Have a ‘tude weiner dude, all right.”), and it made angst so attractive, so important, essential. It made me pretend to like “My Sharona” (“Turn it up. You won’t be sorry”), had Crowded House on the soundtrack, sold torturous angst straight-up with U2’s “All I Want is You”, and it brought “Stay, I Missed You” into the world, which was the song that was playing when I was asked to dance by the coolest boy at summer camp (and, sadly, this was to be the peak of my romantic life for years and years and years).

I was a deeply impressionable 14 years old when I first saw Reality Bites, and it came to define “cool” for the remainder of my teenage years and beyond: smoking, vintage dresses, ’70s nostalgia, passionate friendship, complicated relationships, the attractiveness of moody boys, and an obsession with self-obsession (“I’m making a documentary about my friends”). It taught us all to define irony so we wouldn’t be caught on the spot, it was David Spade at his finest (“Have a ‘tude weiner dude, all right.”), and it made angst so attractive, so important, essential. It made me pretend to like “My Sharona” (“Turn it up. You won’t be sorry”), had Crowded House on the soundtrack, sold torturous angst straight-up with U2’s “All I Want is You”, and it brought “Stay, I Missed You” into the world, which was the song that was playing when I was asked to dance by the coolest boy at summer camp (and, sadly, this was to be the peak of my romantic life for years and years and years).

Because I couldn’t find Reality Bites at my local video store and the Toronto Public Library had not seen fit to update its VHS copy, it seemed like all my wishful thinking had conjured the Tenth Anniversary DVD I bought a few weeks ago at a yard sale for a dollar. I sat down to watch it last Friday night with an aim to craft a blog post about literary references in the film. Except that there weren’t any. Nobody reads in Reality Bites, not even Lelaina Pierce, college valedictorian, or Troy Dyer/Ethan Hawke, the greasy-haired philosophy drop-out. Who says things like, “I might do mean things, and I might hurt you. and I might run away without your permission… and you might hate me forever. And I know that that scares the shit out of you because I’m the only real thing that you have.” And what scares the shit out me is that fifteen years ago, I would have considered these lines incredibly romantic.

It’s true, all the movies I spent my teens and twenties thinking were romantic actually turned out to be fucked up stories about people who were emotionally crippled or mentally ill. Perhaps both forces were at work in Reality Bites (and really, we all know how things turned out for Winona). Reality Bites, the land where nobody reads, but people quote 1970s sitcom trivia at parties and Melrose Place is a cultural reference point. “Melrose Place is a really good show,” said Winona, and I’m not sure that I really agree, but I do think that Reality Bites is a really good movie. Still.

It’s an old, old story, contrary to what the newspapers would have you believe. It’s hard be out just of school, to be transitioning to adulthood, to be unemployed or underemployed, to not know where you want to go, and to have your actual options be even more limiting. To have goals but no idea how to make them realities. It’s hard to have ideals in the real world, to make things that matter, to settle down without settling, to decide who to fall in love, and when not to dress like a doily. It’s terrible to spend four years working towards adulthood, and then emerge into the world to find it utterly unwelcoming. To think that you’re not going to be able to have the kind of life your parents did, even if you’re not sure you want that life in the first place. To not get what you’ve been raised to think was your entitlement. To step out into the air and discover that you can’t fly.

We all know that each generation imagines that it discovered sex, but it’s true also that each imagines that disillusionment is something new. Reality Bites says otherwise: being 23 has always, always been terrible, but thankfully being 23 manages to not be the end of the world. It’s only the very beginning, and you learn.

October 10, 2011

What Sally Draper must have been reading: Virginia Lee Burton and Mad Men

Virginia Lee Burton’s father was an engineer, and her mother was an artist, which is probably a surprise to nobody familiar with her work. Burton’s early books (Choo Choo, Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, Katy and the Big Snow) are celebrations of man’s power to harness his environment with the use of technology, Burton’s vivid illustrations investing her fascinating machines with life and personality. Even 80 years after the publication of Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, that steam shovel Mary-Anne appeals to young readers, and part of that timelessness is that Mary-Anne’s story of technological prowess (she could dig as much in a day as a hundred men in a week) was already about nostalgia even when the book was new. Burton’s work does not become dated, because within it she has acknowledged the passage of time. Mary-Anne was already the relic of a dying age, steam shovels being replaced by diesel-powered diggers, and Burton showed even as she glorified technology that progress did not necessarily lead to better.

Virginia Lee Burton’s father was an engineer, and her mother was an artist, which is probably a surprise to nobody familiar with her work. Burton’s early books (Choo Choo, Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, Katy and the Big Snow) are celebrations of man’s power to harness his environment with the use of technology, Burton’s vivid illustrations investing her fascinating machines with life and personality. Even 80 years after the publication of Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, that steam shovel Mary-Anne appeals to young readers, and part of that timelessness is that Mary-Anne’s story of technological prowess (she could dig as much in a day as a hundred men in a week) was already about nostalgia even when the book was new. Burton’s work does not become dated, because within it she has acknowledged the passage of time. Mary-Anne was already the relic of a dying age, steam shovels being replaced by diesel-powered diggers, and Burton showed even as she glorified technology that progress did not necessarily lead to better.

But the pastoral age that Mike Mulligan… hearkens back to is a pretty curious one. Children have always loved this book because children are fascinated by machinery and learning how things work (Burton: “Children have an avid appetite for knowledge. They like to learn, provided that the subject matter is presented to them in an interesting way”), but for an adult-reader to understand Mary-Anne as the story’s heroine represents a significant departure from how we in the 21st century have come to understand our relationship to the environment. Mary-Anne who can level hills to make roads for automobiles to drive on, and dig holes to turn grassland into skyscrapers, and is powered by filthy coal– that Burton’s steam shovel continues to be a lovable storybook character is a testament to the enduring qualities of her book as a whole.

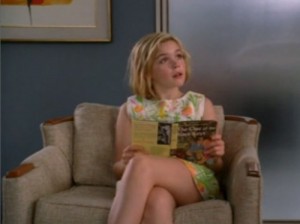

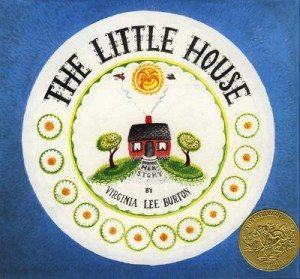

Mike Mulligan was published in 1939, and in 1942, Burton published her most celebrated book, The Little House, which won the  Caldecott Award that year (whose ceremony, it is noted in Barbara Elleman’s fascinating biography Virginia Lee Burton: A Life in Art, was attended by Lillian Smith, president of the Children’s Library Association and head of children’s services at the Toronto Public Library). And from these dates and these books’ acclaim, we can only assume that both found a place within the personal library of Sally Draper, who was born in 1955. Unlike her parents, Sally is rarely seen reading (until Season 4 when she’s spotted with a Nancy Drew), so the contents of her early library can only be inferred, but if the connections between Burton’s world and the Man Men universe are any indication, these books should be an essential part of any Mad Men reading list.

Caldecott Award that year (whose ceremony, it is noted in Barbara Elleman’s fascinating biography Virginia Lee Burton: A Life in Art, was attended by Lillian Smith, president of the Children’s Library Association and head of children’s services at the Toronto Public Library). And from these dates and these books’ acclaim, we can only assume that both found a place within the personal library of Sally Draper, who was born in 1955. Unlike her parents, Sally is rarely seen reading (until Season 4 when she’s spotted with a Nancy Drew), so the contents of her early library can only be inferred, but if the connections between Burton’s world and the Man Men universe are any indication, these books should be an essential part of any Mad Men reading list.

Part of the appeal of both Mike Mulligan and Mad Men is our own nostalgia, but the nostalgia already implicit within these works’ conception of modernity makes our own present ring doubly hollow. In both works, the Future is now, and the present is shining, but something essential has been irrevocably lost, and it has been too late to turn back forever now.

Modernity is symbolized by the city in Mad Men, and also in Burton’s work, no more so than in The Little House. In both works, the city is to be escaped from, its edges a pastoral idyll, though in both works, the city is creeping. In Mad Men, this is shown by suburban life’s failure to be protection enough from the vices and sordidness the city entails. Even in Arcadia (ie Ossining NY), there is infidelity, family violence, divorce, and women lock themselves in the house all day, drinking too much and smashing chairs up. The outside world is brought in every night by the dad in his hat coming home on the train, and by the television’s incessant blare.

Modernity is symbolized by the city in Mad Men, and also in Burton’s work, no more so than in The Little House. In both works, the city is to be escaped from, its edges a pastoral idyll, though in both works, the city is creeping. In Mad Men, this is shown by suburban life’s failure to be protection enough from the vices and sordidness the city entails. Even in Arcadia (ie Ossining NY), there is infidelity, family violence, divorce, and women lock themselves in the house all day, drinking too much and smashing chairs up. The outside world is brought in every night by the dad in his hat coming home on the train, and by the television’s incessant blare.

The creeping is literalised in Burton’s The Little House, which sits contentedly on its hill as the sun goes up and down, and as the seasons change. And then the lights of the city began to seem closer, and roads appear (courtesy of that same steam shovel we know so well from Mike Mulligan, as Harriet is always delighted to point out). There are new houses, and then the buildings around the house grow higher, and a subway is dug underneath, and trams run back and forth, and eventually the house is left abandoned and unloved in the middle of an urban wasteland. (And in this book, indeed, Burton has presaged and synthesized the ideas of Rachel Carson and Jane Jacobs).

But the book’s conclusion is as curious as is Mary-Anne’s status as hero instead of villain. The story of The Little House is resolved when a great-great grandaughter of the man who’d built the house discovers the place in its derelict state, and decides to move it back out to the countryside. Traffic is halted as the house is lifted up from its foundations and placed on a truck, then driven down a big road, then a small road, and eventually the house is settled down on a little hill much like the one it once called home (before that first hill was levelled by a steam shovel). Same apple trees and flowers, and the house can see the sky again, the sunrise in the morning, the moon shining high at night. “The stars twinkled all around her…/ A new moon was coming up…/ It was Spring…/ and all was quiet and peaceful in the country.”

The first few times I read this book as an adult, I figured the moral had something to do with white flight, and the death and death of the  American city. Until I realized that Burton hadn’t presaged Carson/Jacobs so much, and then I thought about the book in the context of its own time, and Mad Men’s. The story’s point, according to Elleman’s book, is that “the further away we get from nature and the simple way of life the less happy we are.” It is a story of the environment with man still at its centre, and with this notion of the city as a place to move away from is an understanding that the space “away out there” is infinite, inexhaustible. (See Kathryn Davis’s Hell and the spaces at the back of medicine cabinets for razor blade disposal in the mid 20th century house– that throwing something “away” was to make it disappear.)

American city. Until I realized that Burton hadn’t presaged Carson/Jacobs so much, and then I thought about the book in the context of its own time, and Mad Men’s. The story’s point, according to Elleman’s book, is that “the further away we get from nature and the simple way of life the less happy we are.” It is a story of the environment with man still at its centre, and with this notion of the city as a place to move away from is an understanding that the space “away out there” is infinite, inexhaustible. (See Kathryn Davis’s Hell and the spaces at the back of medicine cabinets for razor blade disposal in the mid 20th century house– that throwing something “away” was to make it disappear.)

In “The Gold Violin” (Mad Men, Season 2), the Drapers retreat further from urban/suburban life by partaking in a rare family outing, a picnic (although they get there in a brand new Cadillac, so modernity has certainly not been left behind). At the end of the picnic (which has involved smoking while horizontal and peeing behind trees), Betty Draper picks up the picnic blanket and shakes away accumulated rubbish, letting it fall down onto the grass where she’ll leave it.

As in Burton’s The Little House, the world away out there is still ours for the taking, to be used and made noble by our relationship to it.

September 11, 2011

Ten Years Later

Like many people, I don’t require an anniversary to allow for reflection about what happened in New York City and around the world on September 11, 2001. So much that has happened since has seemed to spin out of those strange few hours on that blue, blue morning– ours was the same sky, and it was beautiful. But, also like so many people, this tenth anniversary has me reflecting on my own proximity to the tragedy, and remembering that it was the first day of my final year of university, how I heard the news of a plane crash on my pink clock radio and how I turned on our tiny TV, and saw the second tower fall. How the CN Tower was dark that night, and watching CNN on the TV at KOS at College and Bathurst where I ate french fries with my friends. It seemed like the end of something, of the world, of innocence, of the old world order, and that would have been bad enough (and perhaps even good, in a sense), but what that day turned out to be instead was the beginning of something, and that something would only get worse. We’ve come of age in a world I never would have imagined on September 10, 2001, that night I sat on my rooftop balcony and pretended I smoked, and longed for something to happen.

Like many people, I don’t require an anniversary to allow for reflection about what happened in New York City and around the world on September 11, 2001. So much that has happened since has seemed to spin out of those strange few hours on that blue, blue morning– ours was the same sky, and it was beautiful. But, also like so many people, this tenth anniversary has me reflecting on my own proximity to the tragedy, and remembering that it was the first day of my final year of university, how I heard the news of a plane crash on my pink clock radio and how I turned on our tiny TV, and saw the second tower fall. How the CN Tower was dark that night, and watching CNN on the TV at KOS at College and Bathurst where I ate french fries with my friends. It seemed like the end of something, of the world, of innocence, of the old world order, and that would have been bad enough (and perhaps even good, in a sense), but what that day turned out to be instead was the beginning of something, and that something would only get worse. We’ve come of age in a world I never would have imagined on September 10, 2001, that night I sat on my rooftop balcony and pretended I smoked, and longed for something to happen.

Where we are now is reflected in Granta 116: Ten Years Later, my second foray into this magnificent magazine. (Events are being held around the world in connection with the launch of this issue. I attended on last Wednesday, with readings and discussions.) With all the memorializing, self-indulgent weeping (mine, I mean) and discussions of my pink clock radio, what’s missing, of course, is context, and here we find it in abundance. Here is the kind of memorial that matters, not so much reliving that terrible day but looking around and seeing where it’s taken us. Though theme is loose– “Why this story? Why this issue?” asked Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer, whose short story “Laikas 1” appears here, last Wednesday at the event at Type Books. The connections are not immediately clear, and sometimes they don’t come clear at all, but that’s sort of the way it is with this sort of thing, with how did we get from here there to here. The trajectory is rarely straightforward.

Phil Klay’s “Deployment” is deeply affecting story of a soldier home from Iraq who’s on the verge of breakdown as he struggles to make sense of what he saw there and the things he did there, and the strange connections (or disconnections) between these and the civilian life he’s meant to live again. In “A Tale of Two Martyrs”, we learn of the human stories behind the events that sparked The Arab Spring. In “Crossbones”, a man searches for his son who has disappeared to Somalia to join an Al Queda faction. There are two stories (on fiction, one not) of men who were wrongly sold by Afghan warlords to the Americans for the $5000 reward they were paying for terrorists.

A strange, wonderful story of a North Korean spy aboard a derelict fishing boat, Libyan graffiti artists, photos of Libyan refugees in a camp on the Libyan border. Elliot Woods writes about a variety of perspectives of American serviceman, underlined by his own wretched experiences. Declan Walsh’s phenomenal “Jihad Redux” tells the story of foreign intervention in the Afghan tribal regions over the last 100 years– the same old story, except it’s not, and understanding why is important. Kathryn’s “Laikas 1” is so terribly funny, and gruesome, and its connections to the rest of the issue exalt the issue entire– this story of the TTC and High Park coyotes so belongs here. Then Anthony Shahid’s “American Age, Iraq” about a Jesuit college in Baghdad that thrived from the ‘thirties to the ‘sixties, and about what “America” represented to the rest of the world before it began to mean “boots on the ground.”

Clearly then, there is a world beyond that long ago view from my balcony (though Kathryn’s story affirms that my Toronto view was there), and here we look forwards and backwards to discover it. Posing questions without answers, and challenging the answers I always figured were obvious, and if you really want to retrace the route from there to here, I’d say Granta 116 would be a essential volume to bring on the journey.

August 25, 2011

The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe

I still haven’t watched the fourth season of Mad Men— I’d like to fix the world in order to have Mad Men perpetually before me. We recently rewatched Season 1 though, and got so much out of it– partly because we watched it first time around when Harriet was still so small, so concentration was limited, plus somehow we missed the pivotal “Babylon” episode, so no wonder I felt the narrative was a little out of sync. It’s an extraordinarily good show, no doubt about it now. Though I have feelings for Don Draper in a way that I haven’t harbored for any imaginary person since Dylan McKay in the early 1990s.

I still haven’t watched the fourth season of Mad Men— I’d like to fix the world in order to have Mad Men perpetually before me. We recently rewatched Season 1 though, and got so much out of it– partly because we watched it first time around when Harriet was still so small, so concentration was limited, plus somehow we missed the pivotal “Babylon” episode, so no wonder I felt the narrative was a little out of sync. It’s an extraordinarily good show, no doubt about it now. Though I have feelings for Don Draper in a way that I haven’t harbored for any imaginary person since Dylan McKay in the early 1990s.

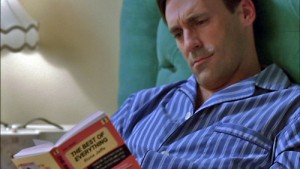

My Mad Men reading also continues– I’m still making my way through The  Collected Stories of John Cheever. For literary illumination into Betty Draper, I had the pleasure of The Torontonians last winter. And I’ve just finished reading The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe, which is a little bit Peggy Olson, a little bit Joan Holloway, not to mention a book that Don Draper himself was seen reading once in bed. (He looks at Betty. “This is fascinating.”)

Collected Stories of John Cheever. For literary illumination into Betty Draper, I had the pleasure of The Torontonians last winter. And I’ve just finished reading The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe, which is a little bit Peggy Olson, a little bit Joan Holloway, not to mention a book that Don Draper himself was seen reading once in bed. (He looks at Betty. “This is fascinating.”)

The Best of Everything is the story of a group of women working at a publishing company in New York City during the early 1950s. Their lives are not especially intertwined, the narrative follows them separately, but they each begin in the same place, working in the typing pool. Smart, beautiful Caroline Bender has been recently jilted by her fiance and is looking for a way to direct her life without him– she has her sights on becoming an editor, but her boss Miss Farrow knows it and is determined to keep Caroline from succeeding (because there is only so much success for women to go around, of course.)

April Morrison is a gorgeous girl from Colorado with no such ambition. She just wants to fit in, and she does after a while. Once she figures out how to reject the advances of her lecherous boss, that is, and reinvents herself with a stylish haircut and new clothes paid for on her charge card. When she lands herself a rich boyfriend, she figures she’s got it made, and it takes her a long time (and an abortion) to realize that he’s been stringing her along. Ever the optimist, however, she starts sleeping with every other boy who comes along in home that one of them will fall in love and make her the wife she yearns to be.

April Morrison is a gorgeous girl from Colorado with no such ambition. She just wants to fit in, and she does after a while. Once she figures out how to reject the advances of her lecherous boss, that is, and reinvents herself with a stylish haircut and new clothes paid for on her charge card. When she lands herself a rich boyfriend, she figures she’s got it made, and it takes her a long time (and an abortion) to realize that he’s been stringing her along. Ever the optimist, however, she starts sleeping with every other boy who comes along in home that one of them will fall in love and make her the wife she yearns to be.

Caroline’s roommate Gregg only lasts at the publishing company a short time. She’s an actress, and she has promise, and she also has a prized contact in David Wilder Savage, the theatre director who becomes her boyfriend. Or he’s kind of her boyfriend– when they show up at the same parties, he always brings her home, but she can never stay. She longs to sew curtains for his bare kitchen windows, and in spite of the openness, there’s always more going on in his life than she is privy to. Eventually, he puts her at a distance and that begins to make do some crazy things.

Then there’s Barbara Lemont, who’s divorced and relies on her job to support her little daughter. When someone finally falls in love with her, every single thing is right about him except that he is married. And there’s Brenda, who’s getting married, and Mary Agnes the office gossip, who is getting married too, and for those two, the job is a stop-gap. But then it never is entirely: “It’s funny, she thought, that before she had ever had a job she had always thought of an office as a place where people came to work, but now it seemed as if it was a place where they also brought their private lives for everyone else to look at, paw over, comment on and enjoy.”

with her, every single thing is right about him except that he is married. And there’s Brenda, who’s getting married, and Mary Agnes the office gossip, who is getting married too, and for those two, the job is a stop-gap. But then it never is entirely: “It’s funny, she thought, that before she had ever had a job she had always thought of an office as a place where people came to work, but now it seemed as if it was a place where they also brought their private lives for everyone else to look at, paw over, comment on and enjoy.”

It’s all a bit of a soap opera, and the endings are too easy, but it all culminates into something more than that, and the book becomes utterly absorbing. Fascinating too that these are the women John Cheever’s characters leave behind when they take the train to Westchester at the end of the day, the kind of women that Betty Draper and Karen Whitney wonder about, when Betty and Karen are the women these women long to be. Almost. And it reminds me of the thing I keep forgetting whenever I think about 20th century history, which was that people were having sex in the 1950s, and willy-nilly to boot. That the more things change, the more they stay the same, and why do stories of beautiful people with terrible lives always seem so incredibly appealing?

August 8, 2011

Going Home Again

“I wonder if ever again Americans can have that experience or returning to a home place so intimately known, profoundly felt, deeply loved, and absolutely submitted to? It is not quite true that you can’t go home again. I have done it, coming back here. But it gets less likely. We have had too many divorces, we have consumed too much transportation, we have lived too shallowly in too many places.” –Wallace Stegner, Angle of Repose

“I wonder if ever again Americans can have that experience or returning to a home place so intimately known, profoundly felt, deeply loved, and absolutely submitted to? It is not quite true that you can’t go home again. I have done it, coming back here. But it gets less likely. We have had too many divorces, we have consumed too much transportation, we have lived too shallowly in too many places.” –Wallace Stegner, Angle of Repose

I don’t get home very often, hardly ever. I’ve never lived in either of the houses where my parents live now, my grandparents’ houses were sold and gutted long ago, the woods behind the house I lived in until I was nine are now so grown-up that you can’t see the house from the road, and I rarely find myself on that road anyway. Wallace Stegner was right. Like Joan Didion, my parents may have wanted to promise me that I would “grow up with a sense of [my] cousins and of rivers and over my great-grandmother’s teacups, would like to [have pledged me] a picnic on a river with fried chicken and [my] hair uncombed, would like to [have given me] home for [my] birthday, but we live differently now.” Which I don’t think is an inconsolable loss, but it’s a loss still, and one I’ve been thinking about a lot lately.

I’m not sure what it is, but I’ve been awash is nostalgia this last while. I keep wanting to write essays about how I spent the night of September 11 2001 in Kos at College and Bathurst eating fries with my friends. This comes on because that night was ten years ago, a nice round number, and because I’ve been listening to Dar William’s The Honesty Room, which I bought around the same time. I keep wanting to write essays about riding our bikes in Japan, and our house in England with its dirty lace curtains and the park across the street, and these wouldn’t be essays, really. They would be diary entries, which, according to Sarah Leavitt, are differentiated from memoirs in that in memoirs, the role of the self is to serve the story. In my story, the role of the self would only be to serve the self, pure indulgence. Basically, I’d like to go home again. Which is as impossible as: Basically, I want a time machine.

I try. Sometimes I walk down Dundas Street between Bathurst and Manning, where I lived for a pivotal year at the turn of the century, except that the Chinese herb shop we lived over is now a store where you can buy a $2400 ottoman, and the restaurant at the end of our block burned down last summer. Sometimes I walk through the university campus where I lived when I thought that a push-up bra and blue eyeshadow were key accessories and where the snow fell so high once that the army came and shovelled us out, but it’s too altogether the same and different. We’ve been replaced by new students who sleep in our beds and imagine themselves to be the centre of the universe.

My family has a thing for nostalgia. A favourite pass-time has always been the Driving By Where We Used to Live game, or the Driving by Where We Lived Before You Were Born game. I sometimes still play this, except we don’t have a car, and so we settle for Pushing Your Stroller Past the Old Apartment whenever we’re in Little Italy. My husband thinks this is weird. Partly because he has lived in none of these locations save for one, and so the game to him is a little bit boring. I keep trying to take him home to places he’s never seen in his life which are inhabited by strangers who have painted the garage door and redone the siding. Besides, he grew up in a land so steeped in its history that he was eager to shed the concept entirely with his new life in Canada. He’s had enough of trodding on Roman ruins. He also thinks it’s funny that any Canadian building one hundred years old is worthy of a plaque.

Anyway, the point is that the cottage we’ve stayed at the last two summers is also where the summers of my childhood were spent. Or not the entire summers, but a few weeks of every one, which, interestingly, have gone all metonymic and become the only bits of those summers I remember. So that last week I did get to go home again, to a place so utterly unchanged, but then I am so changed that it’s a new place altogether and I am happy with that, because I certainly don’t want our summer vacation to be one of those drive-by games that makes Stuart exasperated. I want the cottage to be a place for Harriet to discover for herself, just like I did, and she doesn’t need to know that the dock used to be broken and sinking, so slippery that you couldn’t run, where our fort was, and that the beach was wider once upon a time, but the minnows are the same, and so are the leopard frogs. It is easier to walk barefoot on gravel than it used to be, or maybe it’s just that the soles of my feet are just hard.

No one needs to know about the two salient selves I remember from there. The seven year old girl with a side-ponytail performing a choreographed routine to the theme from Jem and the Holograms on top of a picnic table, and the other one even more awkward, if you can believe it. She’s sitting on a swing dreamily, listening to “Damn I Wish I Was Your Lover” on the yellow Sony Sports Walkman tucked into the kangaroo pocket of her baja jacket. She’s staring at the sunset sparkling on the lake, and she’s thinking of profound things, like boyfriends, and breasts, and one day being so far away that she’ll be able to refer to herself in the third person.