October 13, 2021

Class Reunion: ENG 369Y 20 Years Later

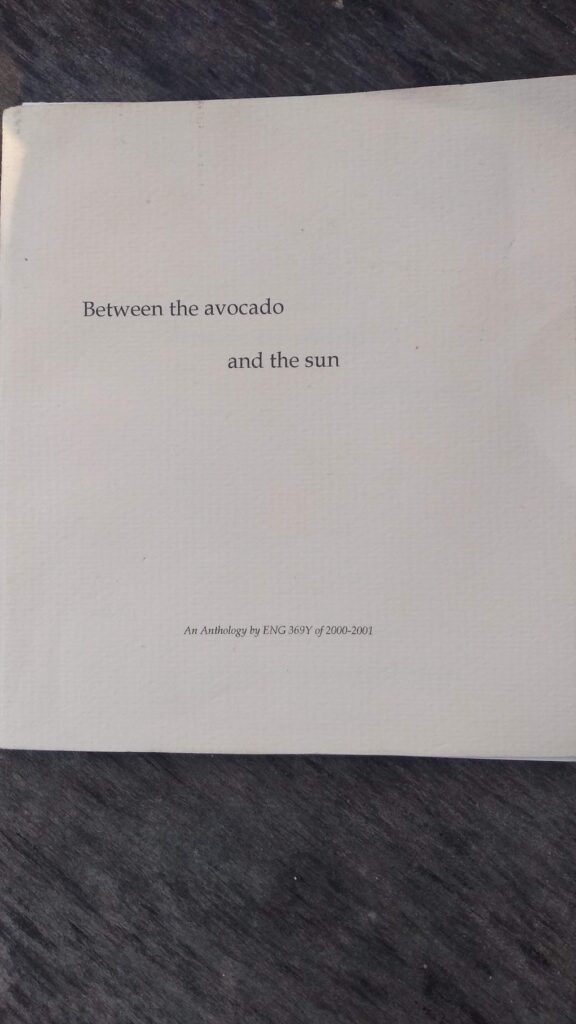

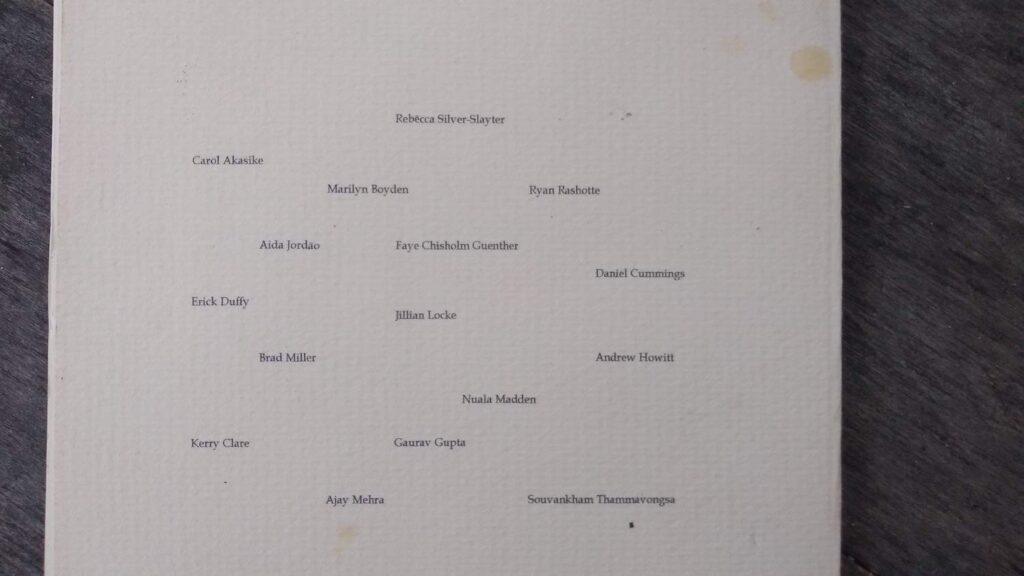

During my third year of undergraduate studies, from 2000-2001, I was part of ENG 369Y, a creative writing workshop led by Dr. Lorna Goodison through the Department of English at the University of Toronto.

For so many reasons, many illuminated below, this class would be an unforgettable experience, though it seemed especially remarkable when—two decades later—four of us from the class would all be publishing books within the same year and a bit.

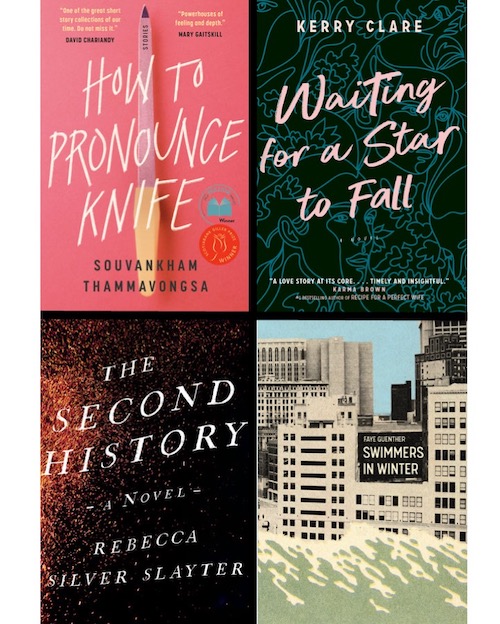

- Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife was published in April 2020, and it was awarded the Scotiabank Giller Prize that year, as well as the 2021 Trillium Book Award, among other accolades.

- Faye Guenther’s Swimmers in Winter came out in August 2020, and it has been a finalist for both the Toronto Book Award and the 2021 ReLit Award.

- My book, Waiting for a Star to Fall, arrived in October 2020, and the Montreal Gazette called it, “Subtly complex […a] romantic drama tailor-made for the #Metoo age.”

- And Rebecca Silver Slayter’s The Second History found its way into the world this summer, with no less than Lisa Moore writing that it’s “one of the most honest renderings of romantic love I’ve ever read. [A] truly mesmeric story, tender, unflinching, quakingly good.”

To me, the serendipitous occasion of our new releases after all this time seemed like an splendid opportunity for us to reconnect and reflect on our time together, as well as so much that we’ve learned about writing in all the years since then, and so the four of us shared our thoughts and ideas via email.

tell us about 20 years in the writing life, about the trajectory of your writing life since our class together in 2000.

Kerry Clare: I don’t think I had a focussed relationship to writing at all in the first ten years after our class together, even as I completed a MA in Creative Writing at the University of Toronto from 2005-2007. There is a line in Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life that I may have misremembered, but it’s about a superficial idea of writer-dom being analogous to one admiring the way one looks in a particular hat, and I always thought she was talking about me, which was mortifying.

When I finished graduate school, I worked for two years reading financial documents all day long, which was not fun, but gave me stability and a salary, though little in the way of creative inspiration. It also gave me parental leave benefits, which I used when I had my first child in 2009, and becoming a parent really seemed to up the stakes for me writing-wise. I became invested in the world in a more meaningful way, and therefore had more to write about. My first big success in writing was an essay about new motherhood I published in 2011, and this led to my first book, the essay anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which I edited and was published in 2014.

At this point, I wasn’t sure that writing fiction was going to be my destiny, and was even making peace with that (throughout this entire period, I’ve been blogging, which has been a creative lifeline), but then something clicked shortly after my second child was born and I finally figured out how plot works. My first novel, Mitzi Bytes, was published in 2017, and I’ve been writing them ever since, and though I am constantly terrified that one day I won’t know how to do it anymore, it seems to keep happening.

Souvankham Thammavongsa: I am not a very good example of a writing life because my trajectory isn’t a simple one and it is not for everyone. I don’t think anyone would want it. I worked for fifteen years in the research department of an investment advice publisher, I counted bags of cash five levels below the basement, I prepared taxes. This work helped me write what I want and it didn’t take away my desire to write. I still have that from 2000, this desire to write, but it wasn’t anything someone taught me.

Faye Guenther: I stayed at the University of Toronto to do undergraduate and graduate degrees in English. Then I went to York University and did a PhD in English. While I was a student during those years, the jobs I had to support myself weren’t related to writing, but they showed me things about the world and this is useful to a writer. I’ve found that no matter what you do, the key is to make the time to write. My writing life has also been shaped by who I’ve met along the way, including fellow writers. In 2017, I published a chapbook of poems and short fiction, Flood Lands, with Junction Books. In 2020, I published a collection of short fiction, Swimmers in Winter, with Invisible Publishing.

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

Rebecca Silver Slayter

Rebecca Silver Slayter: I decided to stop writing not long after that workshop. I think, to reverse what Souvankham said, I worried my desire to write might be something someone had taught me. That I had lost track of why I wanted to write at all.

So I stopped for a year. Or two. Or three? It felt like forever because I was 20-something and everything was forever.

And meantime I decided to make my life and work writing-adjacent. I interned at Quill & Quire and The Walrus. I worked for a startup children’s publisher. I did odd jobs to complete the financial math, yardwork and errands. Eventually I was hired for my dream job, working as managing editor for Brick literary journal.

Sometime in the midst of that, I met my husband, and told him, proudly, how I had made the tough, mature decision to give up writing, and he listened and nodded and then said, I know you are a writer, with such certainty that I didn’t know how to doubt him and I began writing again. And I found to my great joy what I had been missing in those earlier writing years; a desire to write that easily overtook the desire to be a writer.

I did graduate studies in Montreal, where I wrote the first draft of my first novel, In the Land of Birdfishes. When I graduated, I returned to Nova Scotia, and bought a house for a song in Cape Breton, which I will be renovating for the rest of my earthly days.

This is for me a very good place to write, near the ocean and the highlands, in a community where music and storytelling are woven into everyone’s daily life. Here I published my first book and then wrote and rewrote and rewrote my second book, which was just released this summer: The Second History. It took me eight years from first draft till now, mostly because I tried to write it faster than I’m able to. It turns out I’m a writer who needs to take my time…

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

what was the best thing the writer you were in our classroom had going for them? And what writing advice would you give that previous incarnation of you? (Though would you even have taken it?)

ST: My intuition. I listened to everyone, and knew when not to. This taught me how to pick through edits. When we see edits, sometimes it’s about the person and their life experience and it doesn’t mean they are right or know but you have to be generous and allow them to have their thoughts.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it. I want myself to encounter and work through those difficult and lonely moments. I don’t want anyone to hold my hand or do me any favours or make it easier or easy. I like the difficult, and I want to continue with that difficulty.

RSS: One of my clearest memories of that workshop was of Professor Goodison saying, as we discussed one of my poems, “You come from preachers, right?”

I was tongue-tied with confusion. “What?”

“Your people, they’re preachers, right?”

I had absolutely no idea what she meant. “No….” I stammered.

“Then why are you preaching at me?” she asked.

Oof. Caught. I was constantly preaching. Trying to find a much-too-simple way of understanding much-too-large things. I had a weakness for sentences that began like “Love was…”

I think somewhere in this is both my weakness and strength as a writer (probably as a human too). It is writing-in-bad-faith to just polish up pretty turns of phrase that sound truish. To go around making tidy summaries of untidy things. But… I think if I mine deeper I can find underneath that impulse what drives me to writing still, and to reading itself… The sense that there is some luminous other way of noticing the world that will make it brighter, stranger, more visible. That certain words can be incantatory, a pathway to looking again and seeing more.

I have two small children, and have found it astonishing to witness language dawn within a person who formerly had none. How each child altered a bit around the language they used. How they learned what it was then to be nervous, even tired, even thirsty. How what began as the ragged, indeterminate longing of a baby’s howl became so clear, so precise, so unmysterious. And I miss a bit the mystery. The wonder of watching a peer being who doesn’t know what yesterday is. But I think there’s another way that language can give us back what experience has made ordinary. And I think that’s what I was searching for twenty years ago and search for still, but with a few degrees more purpose. And a lot more joy.

So I would maybe advise myself something like this: First, don’t write any more poetry. You are very bad at it. And for a time, don’t write at all. Wait until the desire to write is something you have to resist. Wait until it wells up in you. And then go find the joy of writing words that make you look again, more deeply.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it.

Souvankham Thammavongsa

FG: I remember being openhearted and creative. The writing advice I would give my earlier self is to be bolder. I think when boldness is combined with a practice of being open with yourself and to the world, there is a sharpening of creative focus that can happen and a strengthening of creative perception, no matter what challenges life brings.

KC: The writer I was in our classroom had no idea how much she didn’t know, and far more confidence that she deserved to have, and I’m so happy she did because being 21 is hard enough. I was not a serious person or a serious writer AT ALL. (I remember that Souvankham appeared to be both, and it was such a powerful example for me, though I think I was still too young to fully appreciate it.)

What a tremendous opportunity to develop my skills that class should have been!! But I did not work all that hard, honestly, too busy checking out my look in the hat, remember? I mainly wrote poetry because you could finish a piece in a few minutes. This did not mean my poetry was good, however, although I think sometimes some of it was.

If I could give that writer I was any advice it would be to write something REAL, instead of something you think sounds like something that could be real. (And find writers you love, instead of reading all the writers you’re supposed to love.)

For the record: I would not have listened.

what roles have literary journals and small presses played in your writing career?

RSS: I know literary journals and small presses better as a worker than as a writer. But I am shaped permanently by my years at Brick literary journal, and by the trips I made then, twice a year, to Coach House Press, where the journal was designed at that time.

The Coach House basement was a kind of church I visited like a disciple of those beautiful machines for cutting pages and laying type … and of the people who made them run and knew the stories of an older Toronto and the mesmerizing adventures then had by not-yet-famous writers. In a way that is both corny and essentially true to me, that is what I feel a tiny part of when I write: all the people in all those tiny offices and studios and nooks making small-press books and magazines; their labours of love, their care and bravery, those parallel arts of ink and paper, alongside those of prose and plot.

They taught me what was foundational to writing; the courage and the care of the work. And the kinds of community it can build.

FG: Reading literary magazines gave me an awareness of community. They were the first space where I was published, and I know this is true for many writers. Smaller presses often foster innovative and ground-breaking work. They frequently publish voices and stories that historically have been marginalized. I think smaller presses are important for energizing and sustaining a vibrant creative culture.

My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance

Kerry Clare

KC: My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance, especially in the wake of the novel I’d written for my Masters thesis that went nowhere (because it was boring!) because I was really feeling kind of discouraged, and then this message from the universe arrived suggesting maybe I should keep going after all. In the next few years, I would publish pieces in TNQ and other journals, and the high of an submission being accepted has never diminished for me. And then Goose Lane Editions, a remarkable Canadian indie press with an impressive history, published The M Word, and did the book such justice. Without literary journals and small presses, I’d be nowhere.

ST: Literary journals teach you things a writing class or editor or a dear friend and family cannot. They don’t love you and are not beholden in any way. They teach you about rejection—what that feels like, what to do with it. They are often the first place where we get to see ourselves in print. It’s important for a writer to understand the difference between seeing yourself in print and publishing a book. They are not the same.

what are your favourite memories of our class?

ST: I remember the talent and fun. There were so many writers in that class who are more talented, more ambitious, more interesting…but they aren’t here, or with books. They became lawyers and engineers and professors. I always keep that in mind. Having a book doesn’t mean I am good.

KC: I have so many memories! I don’t know if we were particularly interesting as a group, or if it was the work of Professor Lorna Goodison in creating community, or just the particular mix of experience and personalities in our class, but I felt very connected to everyone. I think we were a well written cast of characters.

I remember Souvankham on the very first day, and how she impressed me so much with her sense of herself. I remember we had to write a poem inspired by postcards, and mine had a field of sunflowers and said, “Welcome to Michigan,” and I wrote a poem with the line, “I won’t forget the motor city.” I remember REDACTED who wrote a poem with the line, “Let’s make love in the astral plane,” and I was seriously impressed by how sophisticated he seemed. And someone else who wrote a poem about someone sucking on her toes while listening to Robbie Robertson sing “Somewhere down the crazy river.” Everyone seemed to be having a lot more sex than me. (One could not have been having less sex than me.)

I remember Faye seemed especially interesting, partly because she seemed kind of badass with a shaved head, and we always sat in opposite corners of the room. And how I was in love with the name “Rebecca Silver Slayter,” which belonged to the woman who often sat in the same corner as me and whose work I felt very drawn to.

I think it’s kind of wonderful that in addition to the four of us, plenty of others in that group have gone on to very interesting careers in academic, television writing, and more.

One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

Faye Guenther

FG: I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from our teacher Dr. Lorna Goodison. One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

RSS: This sounds like very cheap, opportunistic flattery, but honestly, though I remember well many of the talented, interesting writers in the class and their poems and stories, what I remember most clearly is the three of you.

I remember how beautifully Souvankham’s work was always laid out on the page in lovely, tiny type—the form so perfectly echoing the work itself, the grace and economy and polish of her words; how her work seemed always already complete, and I was stumped on how to write any feedback that didn’t just feel like tampering.

How Kerry’s writing was funny and powerful at the same time, and I hadn’t even known that was possible. How she seemed so at home both on the page and in the classroom, warm and open and at ease in a way that awed me. I remember Faye’s compassion for her characters, their rich interiority. How reading her stories felt like someone whispering in your ear, that intimate.

My strongest memory of the class was the first one. When we went around the room and each offered up our names.

Souvankham was near the end, seated at the table perpendicular to the one where Professor Goodison sat.

After she said her name, Professor Goodison asked, “So what do you want to be called?”

I was caught off guard by the question, but Souvankham answered clearly and immediately. Without blinking or skipping a beat, she said: “I want to be called a writer.”

Professor Goodison looked at her and Souvankham looked back. Then she said, “I’m going to call you Sou.”

And I was as astonished as if Souvankham had wafted out of her seat and up into the air between us. I was at that time so uncertain, so full of twenty-one-year-old desires to be interesting, to be brave, to be invisible and/or famous. I would have probably told Professor Goodison she could call me whatever she wanted. Or tried to guess what she might prefer me to be named.

Year by year over these last twenty, I get a little closer to what Souvankham already had then. That certainty. That clarity of purpose and identity as a writer that struck me silent when I was twenty-one.

September 21, 2021

The End of Political Contempt

In September 2020, something shifted for me, after an agonizing decade of partisan politics. It was a decade that began with the inexplicable election of Rob Ford as our city’s mayor, complely bursting my comfortable left-wing Twitter bubble, continuing on to you-know-who’s election to the White House in 2016, and then Rob Ford’s less likeable brother becoming premier of Ontario in 2018. Which would kick off a roller coaster of a four year term in which incompetence has been matched only by sheer callousness.

So much has been terrible in Ontario since 2018 that it’s easy for all the specifics to be lost in a whirlwind of nightmarish absurdity. From the widespread consultation of parents on school curricula whose results were never released, to random plans to scrap the full-day kindergarten program, undermining conservation authorities to permit development of green space, policies keeping communities from accessing developer funds to build vital infrastructure, plans to gut public health programs, and so much more—including the egregious act of arbitrarily interfering with Toronto’s municipal structure in the middle of an election, subverting the democratic rights of millions of people.

Labour disputes beginning in the fall of 2019 meant that the school year was regularly disrupted right up until schools closed altogether due to Covid in March 2020—and children in Ontario would remain out of school for the following 18 months longer than anywhere else in the country.

But when schools reopened in September 2020, I just couldn’t do it anymore, the fighting, the anger, the rage. I could no longer go on treating the government as my adversary. It would be impossible to send my children to school and preserve my mental health under such an arrangement, and so I had to shift my perspective. It helped too that the government—in spite of numerous pandemic failings, in particular in the area of long term care, resulting in thousands of devastating deaths—stopped behaving egregiously with such consistency, and seemed to understand (although always too late, always as a reaction) that people need governments after all. And while they weren’t a great government, or even a particularly good one, they were the government that we had right now and I had to put my trust in them as we made our way forward into a most uncertain future.

When I look back on the last five years of my own political action, there’s a lot that I reflect on. I am grateful for the empowerment and unity of the women’s marches, for example, the first time I ever walked in a crowd carrying a placard. But I wonder too if we’d be seeing the same display of rabid right-wing activism today, seemingly ordinary moms putting their kids on display, if there had been no pussy-hatted inspiration. (Those people have never had an original idea in their lives.) I have also reconsidered my feelings about the government of Ontario’s illegitimacy after they were elected in 2018, joining in calls for leaders to resign. While I do think this government’s tenure has brought significant damage to our province and its institutions, both the last year in American politics and our most recent election in Canada have underlined to me how fragile our democracies are and that those who try to delegitimize democratically elected governments do so at all everyone’s peril. And I’m thinking again about the power of rage as a political tool, which seemed all fine and well when we were raging for our own truly noble causes, but what happens when other angry people start to use that tool too, and their anger is cruel, divorced from reality and terrifying?

When I look back at the last five years of my own political action, what I regret is the contempt I felt, contempt which is not so different from that which resulted from Barack Obama’s political success in 2008, and which has a direct line to the election of Obama’s successor 8 years later. It was actually Trump’s election which made our own contempt for Premier Doug Ford all the more vociferous—does the world really need more than one yellow haired angry populist? (Apparently we needed three.) But of course it was contempt for the previous premier, Kathleen Wynne, that had paved the way for Ford’s unlikely win in the first place.

“Contempt is the opposite of empathy,” Edward Keenan wrote earlier this month in The Toronto Star. “And as U.S. President Joe Biden has said, “empathy is the fuel of democracy.” If we cannot imagine ourselves in the shoes of other people, we have little hope of working with them in a healthy democratic society.”

The Ontario government has been terrible and inept, but they were voted in—not for better, but for worse, it’s true—by a fair election by my fellow Ontarians. And this idea that I myself perpetuated that somehow those people’ votes were less valid than mine or didn’t matter is so absolutely anathema to a functioning democracy—and we see the same dynamics playing out now in far right politics underlined by racism and white supremacy. “Canada use to be a great country to bad its not anymore cause of people like you,” in the brilliant words of a friend-of-a-friend on Facebook last week, and you could almost print that on a little red ball cap, you know?

“I don’t know how to explain to you why you should care about other people.” In the tidal wave of despair that was 2017 and onward, that viral phrase (often mis-attributed) was something to cling to, so perfectly articulating the powerlessness and despair that so many of were experiencing in the face of cruelty and obtuseness. The first time I saw that phrase, in a tweet, no doubt, I am sure that I RT’d it. THIS. But here is something else I’m thinking twice about, this politicization of care, or maybe the partisan politicization is what I mean, because care is certainly political. But I’m resisting the arrogance now that me and people who think like me occupy a kind of moral high ground, and that people who vote for other political parties don’t care for other people too, that they aren’t good neighbours, and generous friends, and charitable donors, and nurses, and teachers, and personal support workers. I’m resisting the idea that in order to care, you have to care the same way I do. I’m resisting the idea that we have no common ground.

Last night was the first election in as long as I can remember that didn’t, to paraphrase Sally Rooney in her latest novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You, “make me feel like I was physically getting kicked in the face.” The election that nobody wanted, perhaps, but its low stakes were almost refreshing—the angry Trumpy man in the purple suit leads a racist fringe part emboldened by anti-vaxxers this time but, statistically speaking in Ontario, our anti-vax population is so tiny that they’re having a hard time spreading the Delta variant, let alone fascism. And while I know details are sketchy and shifty, the other parties were all talking about vaccine mandates, and climate change, and the PC leader was at least trying not to come across as a troglodyte who wants to get all up in my uterus, and I’ve got to give him points for that. It’s certainly better than the alternative.

It’s certainly better than the alternative. A phrase that’s occurred to me several times in the past year or so, especially since we’ve seen the alternative, glimpsed on January 6 in Washington DC, in democratic crackdowns in countries like Belarus and Afghanistan, and so many more, places where political contempt has opened the door to extremism bringing forth a vicious spiral of democratic unravelling. I don’t want to do that anymore.

January 14, 2021

Celebration Wednesdays

#CelebrationWednesdays is a thing I made up yesterday as an excuse to be baking a cake with rainbow sprinkles in the middle of a roller coaster week. Roller coaster week in the pandemic sense, of course, which meant that I barely left the house, but the world has been hard and the weather is grey, and I’ve had plugged ears since Boxing Day that have only become worse since I started squirting random liquids into them in order to ameliorate the situation.

And so the answer was cake. (The answer is always cake.)

I made Smitten Kitchen’s confetti cake with butter cream icing, and it was so very delicious. And I determined that, for the duration, we’ll be celebrating something ever Wednesday, no matter what. And yesterday, that celebration was vaccines. The friends of ours who work in health care are beginning to get theirs. Our friends in New York are getting theirs too. A friend told me that school staff in Ontario will be among the Stage 2 vaccinations too, which is the best thing ever, and it all makes me so happy and is definitely reason to celebrate. It will be some time before I get the shot myself, I suspect, but seeing as I don’t get out much these days, I’m willing to be patient.

Right now I am reading Penelope Lively’s A House Unlocked, the story of her grandparents’ house in Southwest England and the role it played as a backdrop to the tumult of twentieth century. During World War Two, Lively’s family sheltered six small children evacuated from East London, and she put the story in a context I’d never considered before, having taken these evacuations for granted as part of history. But how bizarre it must have been—officials would come to rural homes and take stock of their capacity, and then inform residents of many people would be arriving. People who would stay for years (and had nits and wet the bed). Can you imagine going through that? What mass organization must have been required. And some of it was very disorganized—Lively writes of plans made for specific people to billeted in particular places, but when the time came, the London stations were so overwhelmed with passengers, they had no choice but to just put them on the first trains available, no matter where they were going.

She also writes about the national spirit in 1939, which I’ve never really thought a whole lot about. During the past year in particular, I’ve found myself wondering if my grandparents ever looked at each other and muttered, “Goddamn you, 1943,” but then of course they didn’t, because my grandfather was away at sea. But Lively writes about the very beginning of the war, about the catastrophic predictions for aerial bombardment from the Germans, which experts had been talking about throughout the 1930s. This was no 1914, “this will all be over by Christmas.” Lively writes, “Anyone alive to official anticipation of what would probably happen in the first days and weeks of war would have been expecting the end of the world they knew.”

The story of these mass evacuations was also one of extreme poverty, vast income inequality, a need “to preempt… mass panic and consequent breakdown of law and order” as attacks began.

Anyway, it all made me think about how there is nothing new under the sun… And about the strangeness of living through history, which I never experienced properly before the last five years or so. I was 22 on September 11, 2001, but for me that was too young to properly understand the implications of those events, or how I was connected to them. One day I think I will write something about how it was watching Mad Men that prepared me for the tumultuous times that we’ve been living through. The visceral way that the show presented what it was to experience the 1960s, the deaths of President Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. (“WHAT IS GOING ON?”)

Anyway, the great thing about Celebration Wednesdays is that they lead to Leftover Cake Thursdays.

Whatever gets you through.

November 11, 2020

Poppies

As most people don’t care about in the slightest, for good reason, I have complicated feelings about Remembrance Day. Sometimes I feel like the messaging and symbolism are manipulative, an idea whose simplicity belies it’s true complexity. My grandfathers were proud of their service in WW2, but it was also them who taught me (in addition to “Don’t tattoo anchors on your forearm”) that what a waste is war. The trauma for the people who fight our wars and their families is often insurmountable, and these people do not receive sufficient support. War is bad for everyone, and while I understand that it can’t be obliterated altogether, I am sure there would be less of it if we didn’t have a massive industry that relies on its existence. The most amazing way I can think of to honour those we’ve lost in wars is to stop sending more people to be traumatized or die, instead of glorifying the waste of human life as sacrifice. One other way is to resist fascism in all its forms—my grandfathers (Canadian Navy), maternal grandmother (WW2 nurse), and paternal grandmother (held down the home front while her husband was away for years) were my OG anti-fascists and may their righteousness be our guiding light.

January 23, 2020

Ten Years

I had some strange feelings about reflecting on the 2010s, mostly because I didn’t. There was a meme going around Instagram stories on New Year’s Eve in which we were supposed to list a highlight from each year, and I even tried to post it, but couldn’t figure out how to get the text to fit, which maybe means that the 2010s were the decade in which I stopped being technologically savvy.

But also, the years all blend together, and so much stayed the same. The decade before was much more filled with upheaval and revolution (they were my 20s after all) but in the 2010s were where the pieces started to fit. I stopped having babies, I began to have something like a career, I finally started publishing books, I made some wonderful new friendships, and maintained old ones. It’s been good, but the decade itself, its distinction, just seems particularly arbitrary. Like—even more than a decade should.

Or do I only think that because when the decade started, I was sitting in the very same place that I’m sitting right now?

Okay. not the exact same place. (We finally bought a new couch, remember?) But the same address, our apartment, which we moved into twelve years ago this April, the longest I’ve ever lived anywhere. I moved in as half of a young married couple, and now I’ve got two kids and I’m forty, and have been married almost 15 years. The little kids who lived next door moved out and went to university, and then moved back in again, although it didn’t do me much good when they did, because now they’re too old to babysit. But, as the middle section of To the Lighthouse, so astutely put it: Time Passes.

Imagining our own story as told from the perspective of the house as Woolf does in her novel (except with less war and death). The people coming and going, coats and jackets hung up on hooks and taken down again, early morning alarm clocks and dinners, and house guests, and holidays, and the quiet weeks where we’ve all gone away, and coming home again, an explosion of luggage, and the babies arriving, and late nights with the lights on while the world sleeps, and the babies grow, and all the books that come in and those that go back out again (returned to the library, or left on the garden walls for any takers), and the birthday parties, play dates, first day of schools, pencilled lines in the door-frame measuring from small to tall, and boots and shoes and sandals in a pile at the door, and the triumphs and disappointments, throughout anxiety and contentment, and these walls have contained it all. Even as spare rooms turned into nurseries and cribs turned into bunk-beds, and empty space turned into clutter—Lego, puzzles, and play-doh—and that ring on the carpet from where I put down a teapot and it melted. How places seem to hold us, even more than time does, and how a single place can hold so much, and so can a life.

April 16, 2019

For This Moment

After listening to a discussion on Metro Morning about a new poll showing that 42% of Canadians “think there are too many non-white immigrants” coming to this country, we left the house today having a conversation about how baffled we are by people’s attraction to this kind of right-wing populist thinking.

I mean, on one hand I get it—here, there is certainty, as well as apparently enticing conspiracy theories on YouTube. It’s about something to belong to, someone else to blame for our disappointments, easy solutions to difficult problems, and it’s easier to just lock the door altogether rather than do the painstaking work of community. Scapegoating an “other” is a great shortcut to community really, or at least its illusion, keeping people from worrying about the problem of how to get along with the neighbours you’ve already got, the ones whose skin tones are the same as yours. I thought about this a lot when Kellie Leitch was going on about “Canadian values” during her failed run for the PC leadership, and considered how far apart her ideas are from mine about so many things, and yet this country has room for both of us. This, I’ve always figured, is kind of the point of this country.

So I get it, but I still don’t get it, how it might be possible to fall under the spell of this kind of dangerous rhetoric.

“I feel like everything important I’ve ever been schooled in was actually training for this moment,” I told my husband this morning on our walk, who said he felt the same.

And it’s not that either of us grew up with deeply progressive values in our families, or in places that were remotely cultural diverse. But it was in the stories I was raised on about my grandfathers fighting against tyranny in World War Two, and lessons learned from the Holocaust, and even Hiroshima. About the brutality and waste of war, the horrors of genocide, of human beings’ capacity to do evil things others. The dangers of nationalism, Japanese internment camps and an immigration policy that was, “None is too many.” (It would have been Indian Residential Schools too, if we had learned about them in schools, which we didn’t, but now kids do.) It was in “Never Again” and Remembrance Day ceremonies, and the wreaths I watched my grandfather lay at cenotaphs to honour fallen soldiers and freedom and democracy. It was in the Underground Railroad, and the words of Martin Luther King Jr., and the books I read, from The Diary of Anne Frank to The Cat Ate My Gymsuit and Iggie’s House. It was what I learned about the atrocities of history, and the necessity to be our better selves, to stand up against injustice, and the fact that one day we might be called upon to choose one side or another.

Didn’t you also imagine Germany in 1933, what side you would have been on? Didn’t you also say, “I’d never have let that happen”? Do you also look around at this moment and see circles where racism has become acceptable, people with dangerous ideas being elected into office, leaders undermining democratic values and institutions just because they can—and they’re even supported? Abortion bans as a harbinger—honestly, did none of these people read their Paula Danziger? We’ve got to stand up now, simply because we can’t do it any sooner.

December 11, 2018

Ode to a Parkette

That the park is being bulldozed doesn’t affect my daily life in the slightest, because we don’t even go to the park anymore, and it’s mid-December so we wouldn’t even if we did. But it’s at the symbolic level where it gets me, this park where I spent some of the best years of my career in motherhood, where I came of age as a mother, so to speak. This park where certainly things have changed over the years—the mysterious disappearance of the bumblebee bouncy toy, leaving the ladybug all alone; the tree in the north end was cut at some point; the tree in the south end that was planted to honour somebody’s grandmother, where the leaves were always changing, and falling, and the ground would turn from ice to mud to summer. Where my children changed—they don’t eat the sand anymore, for example—and certainly I did, but the fundamentals stayed the same. The bench on the east side that was missing a slat, and the boarded-up house behind the baby swings that made all of Harriet’s baby photos look like she was swinging out front a crack den, and the little hill on the south side which was perfect for tobogganing on days when you just don’t feel like climbing big hills.

The people were always changing too, and in the beginning there were none of them, just Harriet and me, and we went to the park since I couldn’t think of anything else to do with a baby, because there are only so many hours a day you can spend at the library. Even though parks aren’t really ideal for babies, other than the swings, and pushing one of those for hours is boring, although less so when you do it while reading a book. I remember Harriet falling face-first in the sand there once, and how she got up licking her lips. Our baby days at the park were as aimless as life in general then, but then she got a bit bigger and things got a bit better, and one of the all time greatest afternoons of my life was spent at that park when Harriet was two and she was content to pretend to be driving the jeep toy for hours, and I sat sprawled across the backseat and read an entire book cover to cover. (It was The 27th Kingdom, by Alice Thomas Ellis.)

It was around this time that I’d met my friend Nathalie, whose children were older than mine and who was blazer of many paths I would follow, chief among them Huron Playschool. When Harriet was two, she urged me to register, but I didn’t make enough money at that time to justify it. Still, when Harriet and I were in the park, I’d seen Nathalie’s son in the park with his play school class, and consider the impossibility of Harriet ever being as old as that. And by the time she was three, she would join him there, skipping off down the sidewalk. Every day at playschool, the children played in the park, and it was where I’d pick her up at the end of the morning. I remember sitting around the sandbox with Harriet during her first week of school, and also I was pregnant, but nobody else knew it yet, and the women I was hanging out with there would eventually become my friends. All those hours we spent in the park, on playschool co-op shifts, and also after, because Harriet had stopped napping and we had no reason to hurry home, and it was spring, so early, but we took our shoes off, and buried our feet in warm sand.

All the children were there. Among the trees, in the arms of statues, toes in the grass, they hopped in and our of dog shit and dug tunnels into mole holes. Wherever the children, their mothers stopped to talk.” –Grace Paley, “Faith in a Tree”

I wrote a blog post about that spring we spent at the park, about the woman who were so kind to me during my second pregnancy, and supported our family in incredible ways, and comforted me through difficult times and promised it would all be okay. Most of these women I see rarely now, if ever, and our children would not know each other if they met, but they were there for me at such a pivotal moment, and in my memory of them all, the sun is shining always. Although I’d read Grace Paley wrong, I’d discover a couple of years later. What a thing—the most shocking revelation of my literary life. “I really thought that they’d been it, those mothers in the park. I really had thought she meant that this, the mothers stopping to talk, was the most important conversation. But it wasn’t, her revelation. Faith needs more than that, chatting women lounging in trees. The world needs more than that, at least if we ever expect to do anything about it.”

The first time I took both my children to the park alone, Harriet got stung by a wasp while I was breastfeeding on a park bench, which was not the most auspicious start, but we found our groove, and as a mother I really found my stride.

There’d be one evening in the years to follow when a friend and I would have pizza delivered to the park, and we’d all eat dinner there, in lieu of home and tables, which meant I was a long way from being that woman aimlessly pushing her baby in a swing, and I didn’t even get to read anymore, because there was usually somebody I wanted to talk to.

Eventually, the park became more special occasion than every day, because daily life became more structured. We’d meet up at the park on weekends and holidays, and during the summer of 2016, there were picnics and potlucks and always pie. I’d see mothers who were there with their babies, and I was a million miles away from them, without a clear idea exactly of how I’d arrived here, although the place was the same. I had two kids who could conquer the big climbers, and they’d fly down the steep slide, and I wouldn’t even have to watch them. I had officially retired from pushing swings.

Last summer, our good friends moved out of the neighbourhood, so we haven’t had pies in the park for awhile, and that the city decided to bulldoze it now doesn’t seem so incongruous. (We did enjoy walking through the park in the autumn, however, on our way home from school, when the park was being excavated as part of a project by the university’s archeology department. Old maps had indicated there had been dwellings on the site, and significant finds included bricks and teacups.)

The park is going to be redeveloped along with the expansion of the University of Toronto Schools next door, who are going to be building a facility underneath it, some of the playground equipment being temporarily located to the vacant lot across the street in the meantime. And by the time it’s all finished, my children will likely be too old for parks at all—who’d ever have thought it? And the derelict house on the other side of Huron is finally being developed, after more than a decade, at least, so maybe we can definitively say that absolutely nothing stays the same, which is the point of cities, and parenthood, and everything.

October 16, 2018

The babysitter is not here.

I need a babysitter. Literally, yes, but also more figuratively too, and I’m having trouble finding the one I need, because teenage girls are so much younger now than they used to be when I was a small child, when I regarded babysitters with the reverence Dar Williams articulates exactly in her song, “The Babysitter’s Here.” A babysitter like Elisabeth Shue in Adventures in Babysitting, pretty much the archetypal babysitter. But if you recall, Shue’s “Chris Parker” character was only available to babysit because she’d just had a date cancelled by her jerk boyfriend—in reality, seventeen-year-old girls are not very interested in babysitting at all. Eleven and twelve-year-old girls girls are actually where it’s at, babysitting wise, but then it’s the same thing that all of us had to deal with when we examined The Babysitters Club series with a critical eye, and realized the girls in the club were just children. No offence to Mallory Pike, but I’m not totally comfortable leaving my children in your care (and besides that, you have a nine o’clock curfew).

I need a babysitter. Literally, yes, but also more figuratively too, and I’m having trouble finding the one I need, because teenage girls are so much younger now than they used to be when I was a small child, when I regarded babysitters with the reverence Dar Williams articulates exactly in her song, “The Babysitter’s Here.” A babysitter like Elisabeth Shue in Adventures in Babysitting, pretty much the archetypal babysitter. But if you recall, Shue’s “Chris Parker” character was only available to babysit because she’d just had a date cancelled by her jerk boyfriend—in reality, seventeen-year-old girls are not very interested in babysitting at all. Eleven and twelve-year-old girls girls are actually where it’s at, babysitting wise, but then it’s the same thing that all of us had to deal with when we examined The Babysitters Club series with a critical eye, and realized the girls in the club were just children. No offence to Mallory Pike, but I’m not totally comfortable leaving my children in your care (and besides that, you have a nine o’clock curfew).

But when I was a child and it was 1985, the seventeen and eleven were indistinguishable from my vantage point, and the babysitters all had feathered hair, and exotic accoutrements like braces and acne. Dangling earrings. To me, they were all beautiful, and fascinating, and a window onto my own future as an adolescent, although I would never be as amazing as they were. (It is likely that they were also not as as amazing as they were.) My babysitters were basically Nancy from the Netflix series Stranger Things, who (along with Winona Ryder) was mostly everything I actually liked about Stranger Things, pure babysitter nostalgia. They had names like Bonnie-Ann, and Sarah-Michelle, and Lisa and Heather. One time we even had one who was actually called Nancy, who lived in a townhouse near Oshawa Centre, and I must have come along when my parents picked her up or drove her home, because I think about her every time I drive down Dundas Street in Whitby, and it’s possible that I only ever knew Nancy for a couple of hours in my entire life.

But there is a kind of presence that babysitters possess, an easy authority. No babysitter ever had to yell at us, because my sister and I were in love with all teenage girls and would have done anything they asked of us. My one episode of defiance came about when my babysitter Lisa had her boyfriend over while she was babysitting us, and I was really uncomfortable with his presence, because I was aware that this was a transgression, but also I didn’t like him, and he was distracting our babysitter from lavishing her attention on us. So after I’d been put to bed, I called downstairs to Lisa and her boyfriend that my parents’s car had just returned to the driveway, even though it hadn’t, and she had to get rid of him out the side door fast. I don’t remember if she brought him back once it was clear that I was lying, or if she demonstrated her anger toward me, but I do know that that was the last time Lisa ever babysat at our house.

But there is a kind of presence that babysitters possess, an easy authority. No babysitter ever had to yell at us, because my sister and I were in love with all teenage girls and would have done anything they asked of us. My one episode of defiance came about when my babysitter Lisa had her boyfriend over while she was babysitting us, and I was really uncomfortable with his presence, because I was aware that this was a transgression, but also I didn’t like him, and he was distracting our babysitter from lavishing her attention on us. So after I’d been put to bed, I called downstairs to Lisa and her boyfriend that my parents’s car had just returned to the driveway, even though it hadn’t, and she had to get rid of him out the side door fast. I don’t remember if she brought him back once it was clear that I was lying, or if she demonstrated her anger toward me, but I do know that that was the last time Lisa ever babysat at our house.

The most magical babysitter ever (“She’s the best one that we ever had…”) was Sarah Michelle, who was so pretty (“pretty” was an essential quality for babysitters to have, as far as we were concerned) and who played with us, which was novel, and she became a kind of legend (I think we built something out of a cardboard box) and I remember too that she came to babysit us again after a break, as she wasn’t magic anymore and didn’t play with us at all. Possibly she’d just turned seventeen and had just started had a date cancelled by her boyfriend, but I recall the disappointment viscerally, one off my earliest heartbreaks. The unsustainability of superstar babysitting, for most ordinary people, is an unfortunate reality. Except for a select blessed few among us, the novelty of time spent in the presence of small children is something that wears off fast.

Which is a fitting place to transition to my own experiences as a babysitter, and the children I was caring for factor very little in my memories of being a babysitter—and how Bonnie-Ann, Sarah Michelle, Lisa and Heather probably don’t think of me at all. My own babysitting memories are set in the 1990s with City TV late night movies on, most notably the 1982 film Cat People, about people who turned into monstrous black panthers, and which was so terrifying that I was afraid even to get off the couch and go into the kitchen and eat all of the pickles in the fridge leaving behind bottles of brine, which was my usual tactic as a babysitter. When I wasn’t eating all their chips and ice cream, that is. “Help yourself to anything in the kitchen,” was a dangerous offer to me in 1994, and many of my babysitting clients would live to regret it. You’d think they’d even stop hiring me, with thoughts toward conserving the grocery bill, but then babysitters are hard to come by, a most precious resource. You take what you can get.

July 18, 2018

Astral Weeks

We were away last week and we brought our portable stereo and listened to the same CDs over and over, which are the same CDs we always listen to when we’re at a cottage—Bon Iver and Kathleen Edwards’ Voyageur, and the Beach Boys, and I bought Joni Mitchell Blue. And also Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, which I would listen to when I was in the cottage alone in the morning when I was drinking my tea and not ready to get dressed yet and my family was already down by the water.

And those mornings listening to Astral Weeks when I was all alone were like a time machine, taking me back to 2004, when I bought the CD. My friend Kate had mentioned it in an email, I think, and I looked for it at Tower Records the next time we were in Osaka. We were living in Japan at the time, which is why my copy of Astral Weeks comes with Japanese liner notes and lettering on the CD case. I bought the CD, and immediately fell in love with it, and “Sweet Thing” has been my favourite song ever since. That lyric, which I really understood having not long before undergone a season of tumult: “And I will never grow so old again.” (I also liked that the “garden all misty wet with rain” from “Sweet Thing” is referenced in Caitlin Moran’s new novel, How to Be Famous, which I read last week in less than a day…)

In 2004, Stuart and I lived in a tiny apartment and slept on a tiny platform below the ceiling that we had to climb a ladder to reach. We were both working as English instructors and had the same work schedule, except for Tuesday mornings when he worked in the morning and my shift was in the afternoon. So on Tuesday mornings I was by myself, and I’d put on Astral Weeks, music that I am quite sure was not long after encoded into my DNA. It’s partly the flute, something about the flute. I don’t know that I know another pop song with a flute in it, or at least that I’ve noticed, but the flute on “Astral Weeks,” the opening track, is one of my favourite sounds. And that lyric, “To be born again. To be born again.” I could relate after getting my life back on track, and beginning to move forward. That momentum—it was exhilarating. And the memory of all that possibility is what overwhelms me when I listen again to Astral Weeks.

The album is the soundtrack to all my memories from 2004 (except the ones where I’m singing “Bad Bad Leroy Brown” at karaoke), though I’m not sure this was really the case. It could have been though, because I had a mini-disk player and later and iPod shuffle, and I’d possibly downloaded “Astral Weeks” onto both these devices, and perhaps it was Astral Weeks that was playing the very first time I read Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, on a trolley ride from Hiroshima to Miyajima. It might as well have been, the two are so connected in my mind—they actually came out in the same year. I feel like Joan Didion would have known something about being caught one more time, if not up on Cyprus Avenue: “And I’m conquered in a car seat. Nothing that I do.” (She probably had a migraine from the Santa Ana.) Madame George also seems like a character from one of her essays—one of the ones where the centre does not hold.

I was also discovering Margaret Drabble for the first time in that period, so her books are connected to Astral Weeks as well for me. The first novel I read was The Radiant Way, whose Esther Breuer lives at “the wrong end of Ladbroke Grove,” which is where Van Morrison saw the subject of “Slim Slow Slider” walking, and maybe he even saw Esther too. And falling in love with Margaret Drabble (and Joan Didion) was such a big deal for me as began to discover who I was as a reader and writer. It was a period in which I developed a habit that I’ve never been able to get back again—underlining words I didn’t know in books and looking them up in the dictionary. I kept a list, and one of them was “avarice,” and I’m not sure whether I encountered that one in a book too, or else it was just the line from “Astral Weeks.”

I was keeping the list because I had been accepted to graduate school for the following September, and I was hoping to improve myself enough in order to be smart enough to warrant being there. (It didn’t really work. Do you know what it is to arrive at graduate school with absolutely no knowledge of critical theory? It is NOT FUN.) I was looking forward to moving back to Canada, and I was also planning my wedding (to someone who never mentioned driving his chariots down my streets of crime, but I know he would do it if I asked him), and really, we were on the verge of everything. I knew it, so it was overwhelming to be there in 2004, the sun shining through our window and rendering everything golden, and outside a pachinko parlour on the horizon. Not long ago, I found our old apartment on Google Maps, and the parking lot next door had sprouted a building, so the sun doesn’t shine through that window anymore, but I’m so glad I was there when it did, listening to Astral Weeks.

“And I will raise my hand up into the night time sky, attract the star that’s shining in your eye, ah just to dig it all and not to wonder, that’s just right. And I’ll be satisfied not to read in between the lines.”

June 20, 2018

Us.

Kent Monkman, The Scream

‘Politically speaking, tribal nationalism always insists that its own people is surrounded by “a world of enemies,” “one against all,” that a fundamental difference exists between this people and all others. It claims its people to be unique, individual, incompatible with all others, and denies theoretically the very possibility of a common mankind long before it is used to destroy the humanity of man.’ —Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

“Not they. Us” —Hassan Ahmed

Please forgive me for stealing my epigraphs from Rebecca Woolf’s Instagram feed. But I just want to take a moment to think about books, to think about Zlata’s Diary, a book about a young girl being a young girl during the siege of Sarajevo in 1993, a book that was compared to The Diary of Anne Frank, much to Zlata Filipovic’s consternation, I recall—because Anne Frank died and Filipovic didn’t want to. I remember reading both these books and imagining my way into the lives of their writers, the recognizable landmarks of girlhood, childhood. There was nothing extraordinary about their lives or their worlds, and that was the very point—how perilous was safety, was everything. How easily these people could be me, and didn’t you think this too when you read book like this? When I used to think that books about the Holocaust were even over-taught (my childhood was absolutely saturated with Holocaust novels), although I don’t think that anymore. Not since I learned that not everyone is reading, or at least reading and realizing how easily it could be any of us. Which is what I thought when I read Sharon Bala’s The Boat People, or even An Ocean of Minutes, which is also about being a refugee, about that desperation. I’ve read so many of these stories that imagining my way into the minds of people who risk everything for the chance of a better life is like a reflex—there is no difference between that mother and me. And I’ve seen enough of the world during these last two years politically and even in terms of climate that has undermined all my certainties about who we are and where we’re going that I’m unwilling to be sure that my own safety will never be in peril, that I will never be the kind of person who has to run. We are all that kind of person, or we all could be, and that’s only my selfish reason for condemning the separation of children and their families at US borders. Let alone the humanitarian one. Acknowledging too that I live in a country with a shameful history of separating children from their parents, a history that lingers on into the present—so this “not them. us.” as well. The Thomas King quote: “You see my problem. The history I offered to forget, the past I offered to burn, turns out to be our present. It may well be our future.” Let’s be as loud and brave as girls in storybooks and ensure that’s not the case.

‘In grade school we studied WWII. Learning about the genocide and the concentration camps and the way a whole group of people were dehumanized and carted off like cattle, many of us said, very earnestly: “I’d never let that happen.” Well now we are adults and guess what? It is happening. We are watching it happen.’ —Sharon Bala. (And now read her blog post, “What to do.”)