July 20, 2016

Everything happened in those five years after my abortion.

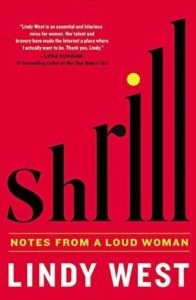

“Everything happened in those five years after my abortion. I became myself. Not by chance, or because an abortion is some kind of mysterious, empowering feminist bloode-magick rite of passage (as many, many—too many for a movement ostensibly comprising grown-ups—anti-choices have accused me of being), but simply because it was time. A whole bunch of changes—set into motion years, even decades, back—all came together at once, like the tumblers in a lock clicking into place: my body, my work, my voice, my confidence, my power, my determination to demand a life as potent, vibrant, public, and complex as any man’s. My abortion wasn’t intrinsically significant, but it was my first big grown-up decision—the first time I asserted unequivocally, “I know the life that I want and this isn’t it”; the moment I stopped being a passenger in my own body and grabbed the rudder.” —Lindy West, Shrill (which I am loving. Particularly the part at the end of this essay, “When Life Gives You Lemons”, when she writes about how if it weren’t for “zealous high school youth groupers and repulsive, birth-obsessed pastors” she would never think of her abortion at all.)

“Everything happened in those five years after my abortion. I became myself. Not by chance, or because an abortion is some kind of mysterious, empowering feminist bloode-magick rite of passage (as many, many—too many for a movement ostensibly comprising grown-ups—anti-choices have accused me of being), but simply because it was time. A whole bunch of changes—set into motion years, even decades, back—all came together at once, like the tumblers in a lock clicking into place: my body, my work, my voice, my confidence, my power, my determination to demand a life as potent, vibrant, public, and complex as any man’s. My abortion wasn’t intrinsically significant, but it was my first big grown-up decision—the first time I asserted unequivocally, “I know the life that I want and this isn’t it”; the moment I stopped being a passenger in my own body and grabbed the rudder.” —Lindy West, Shrill (which I am loving. Particularly the part at the end of this essay, “When Life Gives You Lemons”, when she writes about how if it weren’t for “zealous high school youth groupers and repulsive, birth-obsessed pastors” she would never think of her abortion at all.)

July 7, 2016

Head in the Stars

Today UofT Magazine tweeted about scientists who inspire us, which reminded me to finally write this post which has been on my mind for awhile. About a month ago, my daughters got Stargazer Lottie (who was inspired by a space-obsessed six-year-old girl AND has been “the first doll in space”), which came with a “Notable Women in Astronomy” poster. But none of the notable women were Canadian, and it occurred to me that I knew of a very notable Canadian woman in astronomy, who was Dr. Helen Sawyer Hogg. Whose work I only knew, granted, because she’d had a page in my Grade 8 science textbook and my friend and I used to make fun of her name. Which is ridiculously stupid, but the point is that I never forgot her name, and googled her years later and discovered her story was fascinating. (Do textbook writers know the indirect routes that knowledge might take, I wonder? They would probably be surprised.)

Dr. Helen Sawyer Hogg received her doctorate degree in astronomy in 1931, which is remarkable in itself. Her husband was also an astronomer and the two of them would work together until his death in 1951. Although Hogg’s work was not as valued as she was somebody’s wife, and she was often expected to do it without pay. Her first child was born in 1932 and Hogg kept the baby at work beside her in a basket while she studied star clusters at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, BC. , where her husband was employed as a research assistant. Later that year she received a grant which was exactly enough to pay for a babysitter, and I am fascinated by the idea of how liberating that must have been—and also what it must be to be consumed by cosmic things and have a baby in a basket at once. How does a person reconcile such a vast difference of scale?

Her story would never cease to be cool. After her husband’s death, she took over many of his classes at the University of Toronto, where the family had moved in the mid-1930s. She also assumed ownership of his astronomy column for the Toronto Star, which she wrote for decades (and which was collected into a bestselling book called The Stars Are for Everyone).

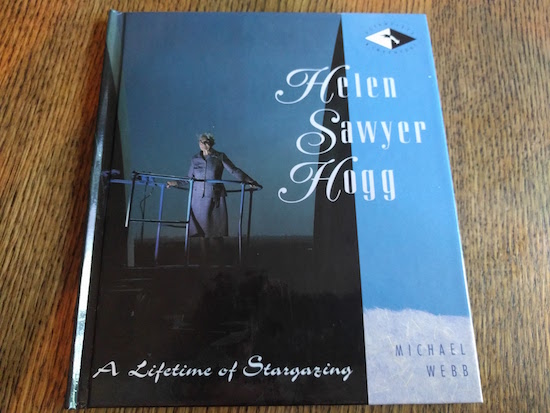

There is no full biography of Dr. Hogg. Editions of a science biography for children was published by Michael Webb in the 1980s and 1990s, and while it’s pretty informative, I’m hungry for so much more depth. And so it seems I am going to have to do some of my own digging. Helen Sawyer Hogg’s archives are at the Thomas Fisher Library at UofT, and I think I’m going to have to make some plans to start going through them. In search of what, I am not sure. A creative project? A biographical article? But there is something here, I am sure of it. I look forward to reporting back on just what I might happen to find.

April 5, 2016

On Putting Politics Aside

On Friday I was listening to CBC Rewind, and heard then-Toronto Maple Leafs owner Harold Ballard on the radio in 1979 telling journalist Barbara Frum to shut up and that females didn’t belong on the radio. And hearing that helped me articulate why I had been taking the heroic eulogizing of disgraced Toronto mayor Rob Ford so personally, why I hadn’t been able to respectfully stay silent while Ford was memorialized (even if he was memorialized with such statements as, “He was a profoundly human guy.” Indeed).

On Friday I was listening to CBC Rewind, and heard then-Toronto Maple Leafs owner Harold Ballard on the radio in 1979 telling journalist Barbara Frum to shut up and that females didn’t belong on the radio. And hearing that helped me articulate why I had been taking the heroic eulogizing of disgraced Toronto mayor Rob Ford so personally, why I hadn’t been able to respectfully stay silent while Ford was memorialized (even if he was memorialized with such statements as, “He was a profoundly human guy.” Indeed).

Now, I knew about Harold Ballard. From childhood, I have known he was an asshole, and though I didn’t know why he was thought to be so, and I suppose any reason anybody would have told me about wouldn’t have been concerned with his views toward women. Another important point is that I’ve been extremely fortunate in my life to be surrounded by men (my dad, my friends, my husband) who make the idea that some men think women are literally garbage (or objects to be knocked over, or raped, or joked about raping, or silenced—I could go on for paragraphs about the ways Ford was disrespectful and hateful towards women) completely baffling and foreign to me. But these men exist, and they end up in positions of power, and because it’s not 1979 anymore it’s not all right to go on the radio and say as much, but there are certain men who aren’t containable and so everybody knows.

And everybody lets it go too. It’s harmless. He’s just a character.

I was dismayed when Toronto’s current mayor came into power and his first motion was to thank Ford for his service. Really? Ford was ill, but regardless, here was an opportunity for a new beginning, a chance to do better than an ineffectual, decisive council that fuelled resentment and anger across the city. A chance, perhaps, to say nothing, and in that silence to tell this city, “We are better than that. We will no longer stand for this. This is not who we are.” To honour the women of this city, the people of colour and gay community, all of whom were derogated by Ford throughout his term in council. That was when saying nothing would have been a respectful gesture.

But not now. Not when Ford was able to milk his whiny victim narrative right into the grave and beyond, and everybody played along with him. History whitewashed: that this was a man who loved his city, the best mayor Toronto ever had, a man of the people. None of it remotely the truth, and the truth matters. And if “putting politics aside” means overlooking abusive, offensive comments about women uttered by people in power, I really don’t think I’m capable of doing it. Basically my politics are that women are people worthy of respect, an idea so elementary, basic and foundational that I can’t imagine putting it aside ever.

I hope that in 40 years the story of Rob Ford ends up on an episode of CBC Rewind, and a young woman listening won’t be able to believe that there was ever such a person like that, instead of seeing such an anachronism reflected in the world all around her.

March 15, 2016

If you wanna be my lover, you gotta get with my friends

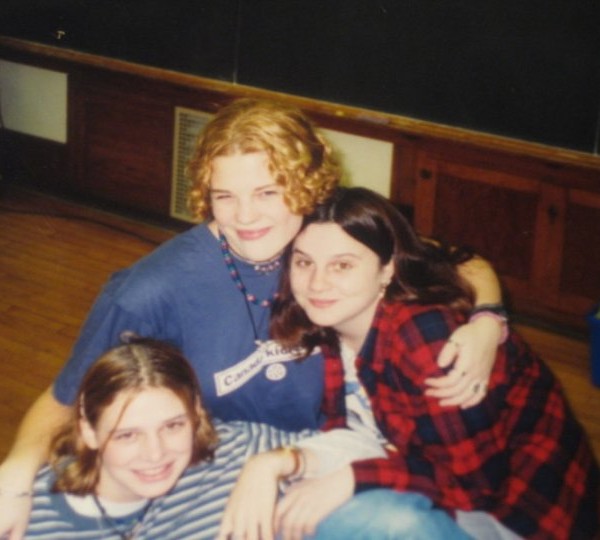

My friends at Plenty are talking about friendship throughout March, and I was pleased to contribute an essay I wrote about my nearly 25-year-old relationship with my best friends, Britt and Jennie (pictured above in Grade 10 French class, I think). I wrote about how with friendships that old, you eventually have a million things to apologize for, and also about how the Spice Girls taught us how a person should be, how our boyfriends were quite disposable, and how (in a numerical feat as remarkable as “2 Become 1”) 3 becomes 12.

February 8, 2016

The Disappearing Woman Writer

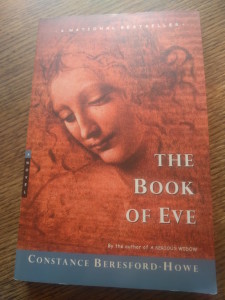

I’ve never read anything by Constance Beresford-Howe. Why not? Because her books were old, their covers not very enticing. That her focus was on older women also would not have meant anything to me for a very long time, would have been a drawback, actually (I’d had been through enough with The Stone Angel; I still don’t really love that book) though I recall that my mom had a copy of The Book of Eve. I never read her because her books were never assigned to me for a class, which the reason that I read many things. I suspect I didn’t read her books for the same reason that women proclaimed our universe “post-feminist” in the late 1990s. But her name was familiar when I encountered it in The Globe obits a couple of weeks ago. (You see, I am now at the point in my life at which older women have become interesting; I pore over the death notices every Saturday.) A name with which I am that familiar should perhaps have the death of its bearer meet with more press than just an obit: “Educator, Author, Lover of Literature.” The Globe’s Marsha Lederman had tweeted about her death, as well as had a few others who’d had her as a teacher at Ryerson. And I was glad when I learned that a longer obituary for Beresford-Howe was in the works. Because, see, I’d recently read the essay, “The Amazing Disappearing Women Writer”, and realized that lack of attention to Constance Beresford-Howe, in later life and in death, was not a literary anomaly.

I’ve never read anything by Constance Beresford-Howe. Why not? Because her books were old, their covers not very enticing. That her focus was on older women also would not have meant anything to me for a very long time, would have been a drawback, actually (I’d had been through enough with The Stone Angel; I still don’t really love that book) though I recall that my mom had a copy of The Book of Eve. I never read her because her books were never assigned to me for a class, which the reason that I read many things. I suspect I didn’t read her books for the same reason that women proclaimed our universe “post-feminist” in the late 1990s. But her name was familiar when I encountered it in The Globe obits a couple of weeks ago. (You see, I am now at the point in my life at which older women have become interesting; I pore over the death notices every Saturday.) A name with which I am that familiar should perhaps have the death of its bearer meet with more press than just an obit: “Educator, Author, Lover of Literature.” The Globe’s Marsha Lederman had tweeted about her death, as well as had a few others who’d had her as a teacher at Ryerson. And I was glad when I learned that a longer obituary for Beresford-Howe was in the works. Because, see, I’d recently read the essay, “The Amazing Disappearing Women Writer”, and realized that lack of attention to Constance Beresford-Howe, in later life and in death, was not a literary anomaly.

In her essay, Jeannine Hall Gailey asks the question: “So, how can the mid-life woman writer attempt not to disappear right before the eyes of prominent male writers, king-makers, editors, judges and juries of prizes and grants? How do we stay seen and heard when perhaps our youthful charms may be diminishing but our art may be improving?”

It was a question I came at as a reader, though I am a writer too with greying hair and a body that is slowly turning into a splendid pudding. But it was as a reader I considered it, how much we are missing. And it affirmed why I do what I do here and elsewhere, championing books from the platform I’ve made, making noise and shouting my darnedest to ensure that women writers don’t just disappear. And that I have to backtrack too, take note of all those books and readers who weren’t bright and shiny enough when I first encountered them, give them another chance.

I was so happy to read Judy Stoffman’s profile of Constance Beresford-Howe in the Globe this weekend, and to have it affirmed that she’s probably a writer I will deeply appreciate, with Barbara Pym comparisons as the cherry on the sundae. I went out on Saturday afternoon and picked up a second-hand copy of The Book of Eve, and look forward to tracking down her other books in time, and to doing a lot of shouting about them.

January 5, 2016

Lottie: Empowering Girls from Outer Space

We discovered Lottie Dolls over a year ago, and their premise intrigued me. A proper alternative to Barbie, designed to empower girls and their play. I wrote about them here (and check out the pictures! Iris was still a baby! Harriet was so little). It could have been a one-time thing, but I return to Lotties because now it’s my girls who are crazy about them. They’re the one toy, along with Legos, that gets returned to again and again, and they play with them together, which I love so much. We have five or six of them, and received more for Christmas, along with two new Lottie outfits, including the Superhero Lottie suit shown above, which has proven very popular—this is the one Lottie who never gets her clothes changed. When Harriet and Iris received Christmas money from their grandfather last week, they knew what they wanted to buy with it—more Lotties. And so we’re currently awaiting Rockabilly Lottie and Spring Celebration Ballet Lottie in the mail, expected delivery scheduled for tomorrow. Everybody is very excited.

Though we’ve also got our eye on Stargazer Lottie, who was sold out from Indigo.ca when we made our order last week. (Darn!). Like all the Lottie dolls, she’s designed around what she can do and be rather than how she looks (although admittedly, once they’re indoctrinated into Harriet’s play, the Lottie dolls also take on peculiar new identities…) I was so interested to read this post about how Stargazer Lottie was designed in consultation with an astronomer, and even more thrilled to learn that a Stargazer Lottie doll was currently in space with British astronaut Tim Peake on the International Space Station.

And most remarkable? That none of this would have happened at all without a six-year-old girl from Comox, British Columbia, who helped dream up the Stargazer Lottie doll. I showed the video below to Harriet who had her mind blown, and then went to put on her own dress with a space print and proceeded to have her head in the stars for the rest of the day, totally inspired.

December 5, 2015

Making and unmaking: when does a fetus become a baby?

The Planned Parenthood shootings in the US last week have brought the pro-life zealots back out of the online woodwork, which means that men have been explaining pregnancy and abortion to me on Twitter again. (At a fraction of the rate before, but still.) I’m still honestly just baffled about how somebody without a uterus could feel entitled enough to tell me anything at all on these topics; it would be like me purporting to teach the Canadian women’s hockey team how to win an Olympic gold. How does a person get to be that sure of himself? To be honest, I’m not sure I’d ever want to be. (From my essay, “Doubleness Clarifies”: “But I’d like such a person to shake their convictions for just a moment or two.”)

The Planned Parenthood shootings in the US last week have brought the pro-life zealots back out of the online woodwork, which means that men have been explaining pregnancy and abortion to me on Twitter again. (At a fraction of the rate before, but still.) I’m still honestly just baffled about how somebody without a uterus could feel entitled enough to tell me anything at all on these topics; it would be like me purporting to teach the Canadian women’s hockey team how to win an Olympic gold. How does a person get to be that sure of himself? To be honest, I’m not sure I’d ever want to be. (From my essay, “Doubleness Clarifies”: “But I’d like such a person to shake their convictions for just a moment or two.”)

These are men who have definitive opinions on the question of when life begins. (And about sluts. And morality. And the right to have extensive collections of weaponry, oddly.) The question of when life begins, however, is one whose undefinitiveness I’m so comfortable with. And I would be, as a woman who has made a choice to end a pregnancy, and who so desperately valued the pregnancies I wanted.

It’s simple: when does a fetus become a baby?

When a woman decides it does.

Women make and unmake our children, not just in the biological sense, but in the ontological sense, too. The fetus is a fetus, and the child a child – only the woman knows. If we deny her the power to define her own pregnancy, we deny the power inherent in womanhood.

From my essay, “Doubleness Clarifies”:

With my second pregnancy, from the moment of my positive pregnancy test, everything was different. The fetus growing inside me was never anything but a baby. We’d been quietly dreaming of her for years, imagining the colour of her eyes, her hair, trying out a parade of hypothetical names. Five weeks into my pregnancy, I bought her a book and we started reading to her even though she hadn’t yet developed ears.

But of course, it’s not really simple. Sometimes I think you have to be a man who hasn’t lived much to ever imagine that anything is. What I find so fascinating and worthwhile about thinking about miscarriage and abortion together is not just the intersections between the two experiences (and that “a single thing can have two realities” after all) but that so many women I know have gone through both. Abortion and miscarriage are not experiences in opposition, but together are threads in the fabric of so many women’s lives, and, however uncomfortably, we learn to decipher, to determine even, the pattern of these threads, how and what it all means.

Women continue to be in control of the narrative, is what I’m saying, making and unmaking, and it’s this control—without which one’s bodily autonomy is impossible; Kimball’s “power inherent in womanhood” —that makes so many people so impossibly angry.

September 23, 2015

Why I keep shouting my abortion

I can’t remember when I started talking about my abortion. When it happened, my girlfriends knew, of course, and obviously so did my boyfriend, but in general, I kept it quiet. I don’t remember why. I think I was profoundly embarrassed and ashamed at having become pregnant in the first place. It was also a terrible time, a really awkward situation in which I had to come home early from my post-university European tour to have the procedure. (I wrote about this all here: I always knew I would. It really was the most interesting thing that has ever happened to me.) I remember other friends inquiring as to why I was back in Toronto, and I didn’t say anything about it. I think I was just waiting for all that time to be over and done with; if I didn’t tell the story, I could imagine that it had never happened.

My husband knew very early in our relationship. I was still quite a bit bonkers about the whole thing when we met, which is not to say that having an abortion was a bad decision, but just that the whole experience (accidental pregnancy, having my life fall apart, etc.) was awful and it took me a very long time to get over it—though he helped by being wonderful and good. And beyond that, in years to come, my abortion was the kind of thing that came up in conversations with friends once we’d had too many drinks. Because everybody’s got a story. I was never ever alone in any of this, but it wasn’t the kind of thing I talked about in daylight.

As time went on, I started to become concerned. Abortion, to which I owe my life, I think, started to become more and more politicized. Or maybe I just grew up and started paying attention. And it bothered me that the only people who were talking publicly about abortion were men who were trying to sign bills to deny women access to it. It was becoming clear that I’d have to become more political as well.

My first public act as a pro-choice person was attending the pro-choice Jane’s Walk in 2011, learning about the abortion landmarks in my neighbourhood, including the clinic around the corner from my house that was fire-bombed in 1992. I had no idea. And as this event took place on Mother’s Day, it only underlined how connected my experiences of abortion and motherhood were, however incongruously (if you are the person who has trouble grasping two realities at once—in recent days, I have learned this is a lot of people). This experience would be the basis of my essay, “Doubleness Clarifies”, which was published in The M Word (and later reprinted in The Huffington Post).

Practicing for the essay’s entrance into the world, I published a blog post two and a half years ago when Dr. Henry Morgentaler died in which I noted that the reason this man was so important to me was not only had he fought valiantly for Canadian women to have access to abortion, but he’d actually performed mine. And there: I’d said it. I was a woman who’d had an abortion. It turned out to not be so difficult after all.

It was particularly not difficult because the support I received in response and in response too to The M Word essay was overwhelming. And I mean my mom and dad buying cases of my book and standing proud in the audience at the launch as I read my essay, to my mother-in-law quietly “liking” my Facebook posts, and my husband never ever getting tired of my increasing comfort with the subject. The people who matter, of course. But also the women who came up to me after readings who whispered, “that was me,” the journalist who wrote about my story and said the same thing, the reviewer whose understanding of abortion had been shaped by her own miscarriages and who with my essay saw it from a different point of view, and the amazing Plum Johnson who I read with at an event filled with 200 suburban matrons and when I confessed that I was nervous about that particular crowd said, “What? You think nobody here has ever had an abortion?”

Truth: I’d rather not be talking about my abortion. Not now at least. And not because it’s painful, or because I’m ashamed, but because it’s history. And because I’m wary of becoming someone who talks about her abortion all the time. As in, “We know Kerry. You’ve told us that story.” Abortion is not my only trick. I am interested in many other things, such as literature, bunting, the upcoming Federal Election, and Devon Closewool Sheep. I’m also wary because I know it seems insensitive to talk about my abortion all the time when my friends and acquaintances have their own stories: infertility, miscarriages, sick children, dead children. But the costs of staying quiet to stay polite are really starting to seem too high. And I really do believe that all these stories are part of the same story, a larger story about women’s lives. So I keep returning to abortion again and again.

In the summer I was walking down Bloor Street pushing Iris in a stroller, having just dropped Harriet off at day camp. We were hurrying home for lunch and nap, but I had to stop at the corner of Bloor and St. George where two very young people were holding pictures of lentil-sized fetuses magnified so they were bigger than I was. (What, when blown up at that level, would not be disturbing to look at?) Now I have walked past pro-life activists many times in my life because I lacked the courage to do anything but, because I do not like confrontation, and yes, because I always have better things to do than talk to people who standing on the sidewalk holding signs.

But it was different this time. Because this time, I’d learned to talk about my abortion in public. And as a person with that knowledge, I had an obligation, I thought, to speak up again. To stop there and talk to that impossibly young girl who’s trying to pass me a pamphlet with a number to call for support should I happen to regret my abortion (“We’re not judging you,” she tells me) and tell her, no no no. To point to my daughter sitting there waiting to be given her lunch, and say, “This is my baby. This baby would not exist were it not for my abortion. This life, this amazing life, my life, would not exist were it not for my abortion.” To say to her, “I have two children and I’ve had an abortion. There I things I know that you don’t know. Do not dare to stand here on the street and purport to educate me. Allow me to educate you.”

“There was nothing I wouldn’t have done to end my unwanted pregnancy, that my desperation had been just the same as that of all those women who’d had unsterile elm bark slipped through their cervixes to induce abortion, but that I hadn’t had to kill myself in order to relieve it.”

For the past few days, the hashtag #ShoutYourAbortion has been trending on Facebook, started by feminist activists Lindy West and Amelia Bonow in the US. (Read West’s piece in The Guardian: “I set up #ShoutYourAbortion because I am not sorry, and I will not whisper.”) This was my kind of bandwagon, so naturally I jumped on, sharing my essay from The M Word. And while the response to the hashtag was just the kind of thing I like to see—this conversation being owned by the women who’ve lived it, who for once are not trying to stay quiet for fear of offending sensibilities. It feels good to talk about your abortion out loud, this thing that made you and to not have to keep the story inside. It’s nice to see the thing I know is true from all those late night conversations over too many beers really is true after all: women have abortions, we get on with our lives, this is an ordinary, quotidian thing, and while the decision can be “harrowing” or “difficult,” sometimes it is just a thing. Sometimes an abortion can deliver the greatest kind of relief.

Of course, the hashtag got hijacked, levels of hatred I’ve never seen before. I don’t engage in online arguments ever, and certainly not with people whose twitter header photos feature their gun collections. I started to realize there was a direct correlation between people with American flags in their header photos, and the need to tell me that I was evil. I suggested to one woman that maybe Jesus (who, according to her twitter bio, was the answer to every question) might have shown some more compassion, and she informed me that unless one had repented, one was against Jesus, with Satan. (I had no idea. They didn’t teach that at my Sunday school.) Murderer. Murderer. Murderer, they said. Along with slut. I saw “trollop” once. I have never been witness to such abject hatred as these people (who claim so much to love babies) have for women who’ve had abortions.

I tweeted, “So much hatred by #ShoutYourAbortion trolls. If you can feel for a lentil-sized fetus, surely you can empathize with actual human woman too?” It’s been retweeted nearly 300 times, which counts as viral by Kerry Clare standards, and favourited 736 times, but this means that I’ve been exposed to even more lunacy, people who want to debate me on this. To what end, I don’t know: it’s not like I’m going to go back in time and not have an abortion. And they keep wanting to tell me things I already know, like that my decision was a selfish one, and there is an odd contradiction in talking about abortion when you’re actually a mother (although this isn’t a contradiction at all, but these people have small minds), and that not all aborted fetuses are the size of lentils (although everyone I know who has ever had an abortion later than 8 weeks or so did so with heartbreak in order to avoid the trauma of carrying a nonviable pregnancy to term, so fuck you asshole), and that unborn babies don’t get to make a choice (welp?), and of course, there is always adoption. Of course there is.

Um, there was also the guy who told me that I was a Nazi who had morals on par with ISIS. Later he tweeted about how he didn’t abort his hydrocephalic baby. The guy was a moron, but I got him then—his feelings spring from a genuine (albeit limited) place that I can understand. I even understand the woman who’s determined to stamp out abortion because of how it hurts women—apparently she spends her days holding other women who are traumatized by theirs. (Perhaps less shame and stigma might ease this kind of pain. Also, where is this woman hanging out? Sounds terrible. She needs new friends.) And yes, many of these people are just people who hate everybody, women in particular. “You shouldn’t be able to have everything you want!!” somebody tweeted at me. “But I can,” I wanted to crow. “I do!!!!”

My husband has finally told me to stop talking. On twitter at least. “These people are crazy,” he said. “These are people who would literally kill you and think that’s okay.” He also points out that I have better things to do than argue online with sub-literate people with eggs for avatars, and he’s right on both points. It’s also really, really exhausting.

So yes, no more twitter exchanges, but I’m not done with the hashtag yet. I’m not done with talking about my abortion either. And I’m guess I’m just laying the whole thing out here so that perhaps you’ll understand why.

May 5, 2015

Motherhood and Creativity: In Conversation with Rachel Power

Everything is a circle. I first learned about Rachel Power’s work through serendipity and (what else?) blogging and talking about books. In 2008, the Australian writer and artist left a comment on my blog about the ambiguous ending to Emily Perkins’ Novel About My Wife, and I discovered her blog and her book, The Divided Heart.

Everything is a circle. I first learned about Rachel Power’s work through serendipity and (what else?) blogging and talking about books. In 2008, the Australian writer and artist left a comment on my blog about the ambiguous ending to Emily Perkins’ Novel About My Wife, and I discovered her blog and her book, The Divided Heart.

At the time, I was pregnant with my first child and so still very much on the periphery of “the motherhood conversations” of which I’d be privy to in the months to come. And so The Divided Heart was my first hint of these, where I first read about maternal ambivalence, the struggle (emotional and practical) for mothers to assert their creative selves, and the myriad ways women find to make it work. It was a hugely important book for me. I read it before I read Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work!

And because everything is a circle, The Divided Heart is now back in print as Motherhood and Creativity: The Divided Heart, and where Power left a comment on an interview I’d done seven years ago, I’m now interviewing her—about the book, how it’s changed in its new edition, the ways in which the motherhood conversation has changed since 2008, and how motherhood can connect us to our creative selves and to the world.

****

Kerry: The Divided Heart was one of my foundational texts on motherhood and mothering—I read it while I was pregnant in 2008. Which seems like a lifetime ago now, but I am so pleased that it has found new life as Creativity and Motherhood. The book played a huge role in my own experience of my heart actually not being so divided when it came to motherhood and creativity—you showed examples of how women combine the two, even when the balance is tricky. These women showed me what was possible. So I really like the new title—but how did the title change come about?

Rachel Power: Thank you for those generous comments about the book. It’s very flattering that someone as well-read as you would consider my book any kind of “foundational text”! I know your book has become the same for so many women out there.

With this new edition, called Motherhood & Creativity, the publishers had some radical changes in mind for the title, which I have to admit I largely resisted. I actually pushed pretty hard to keep “The Divided Heart” in there (it became the subtitle), because I still believe it represents the central drama of the experience for many if not most creative people with children: the desire to be in two places at once; the fear that being properly dedicated to one role inevitably risks neglecting the other. For me, those words introduce the initial question the book is trying to address. But as you say, that doesn’t mean it is full of women who are bogged down by those feelings; rather, it’s full of examples of artists who’ve found ways to forge ahead despite, and sometimes because of, those dilemmas.

With this new edition, called Motherhood & Creativity, the publishers had some radical changes in mind for the title, which I have to admit I largely resisted. I actually pushed pretty hard to keep “The Divided Heart” in there (it became the subtitle), because I still believe it represents the central drama of the experience for many if not most creative people with children: the desire to be in two places at once; the fear that being properly dedicated to one role inevitably risks neglecting the other. For me, those words introduce the initial question the book is trying to address. But as you say, that doesn’t mean it is full of women who are bogged down by those feelings; rather, it’s full of examples of artists who’ve found ways to forge ahead despite, and sometimes because of, those dilemmas.

As for using the word “creativity” instead of “art” (the original subtitle was “Art and Motherhood”), this felt like a necessary recognition that creativity is an important part of many people’s lives, expressed in different ways, but that doesn’t mean they all identify as “capital-A” artists. That’s why I really wanted craft-maker and blogger Pip Lincolne in this new edition: she has such a strong creative drive—and such a creative approach to life!—but I don’t think she would identify as an artist, as such. I knew that many readers would relate to that.

Kerry: It’s a very different book for me now—not just in title. I’m much more experienced in both motherhood and being creative than I was in 2008, and I relate to different parts of the conversations. How has the book changed for you? Was revisiting it a welcome experience?

Rachel: Like you, of course, I’m much further along in my parenting (my kids are 13 and 10 years old now!), but the issues remain very current to me, so I found it easy to slip back into the mothering and art conversation for the new edition. The demands are different, but just as intense, I find. With my son starting high school this year, I feel like I’m going back to school myself—my weekends have been almost completely hijacked by helping him with his homework!

But one of the main realizations for me, as someone who works full time, is that holding down a day job has been a much greater barrier to creativity than mothering. In the first edition, writer Anna Maria Dell’Oso said that when she was at home with small children she felt much closer to “the centre of her integrity” than when she was at the office, and I totally relate to that now. Finding time for art is a big challenge when your kids are small, but the upside is that in some fundamental way, we are already in a very creative space as parents, even though it’s hard to recognize that at the time.

“Finding time for art is a big challenge when your kids are small, but the upside is that in some fundamental way, we are already in a very creative space as parents, even though it’s hard to recognize that at the time.”

Kerry: What about the book’s actual changes? What else is different in this new edition?

Rachel: The new edition contains around half of the interviews from the former book and the same number again of new interviews. Much like the first time around, I approached women I admire, and was lucky enough to interview one of Australia’s best-loved actors Claudia Karvan; visual artists Del Kathryn Barton and Lily Mae Martin; writers Cate Kennedy, Tara June Winch and Lisa Gorton; musicians Holly Throsby and Deline Briscoe; and craft maker and blogger Pip Lincolne.

The other coup this time around was adding a preface from musician Clare Bowditch, who as an old friend and neighbour of mine, not only witnessed the genesis of this book, but also shared in the early years of child-rearing with me. So apart from my own family, there is really no-one closer to this book than Clare, and her preface is affirming and moving and humbling all at once. I’m very grateful for it.

My introduction and conclusions in the first issue are heavily truncated into one opening chapter in the new book. I had done a lot of research before writing the first edition and basically presented my poor editor with a 140,000-word thesis! This was cut back heavily, obviously, but the new publishers felt that it was still a bit too academic in style. So the new intro is a bit less wordy and hopefully more accessible as a result.

Image by Launch Bubble

Kerry: How did the new edition come to be? What were the signs that the demand for it was out there?

Rachel: The Divided Heart went out of print a while ago, and it was really upsetting me that people couldn’t get their hands on a copy. I was still getting lots of letters and emails from potential readers asking where they could find books, but I only had one copy myself! So it was very exciting to find a new publisher in Affirm Press. Initially, it was just going to be a shortened version of the original. But as we went forward, editor Aviva Tuffield and I decided that it would be good to create a different book, to bring it up to date, and so there was new value for those who already had the original edition.

Kerry: Are you finding the reception different this time around? My sense is that we’re living in a slightly different climate now in regards to talking about motherhood—there is more space for nuance. Though this might be because I’m now in that climate instead of looking on. What do you think?

Rachel: That’s an interesting observation! I think there is definitely more space for nuance in the feminist debate generally, and that we have largely moved on from the dispiriting “mummy-wars” that were dominating the conversation around the time I first published The Divided Heart. Motherhood has definitely taken centre-stage in a way it hadn’t when I had my first child, and so there seems to be less division between the different parts of people’s lives nowadays—and between those who have kids and those who don’t—which can only be a good shift for society, I think. That said, most of the criticisms I’m receiving this time around are the same as last time: chiefly, that this is a bunch of middle-class women indulging their hobbies and complaining about their kids (which is such a tedious misrepresentation of the actual stories it contains).

From the outset, part of what interested me in the subject of artist-mothers was that I saw the unique contribution it could make to the feminist debate, precisely because it is a nuanced issue—both in terms of work/economics and of family/housework. Writer Alice Robinson summed it up beautifully in her recent piece for Overland journal, when she said that “as a stay-at-home parent by day, a writer by night, I am doing what untold numbers of people in each camp, and all those in both, are doing: two challenging but largely unpaid jobs. … each undervalued in the remunerative sense, but fundamental in the cultural.”

“To have a child is to enter into a strange new set of negotiations with society, our partners, our family, ourselves. To also be an artist, it seems to me, is to be dealing with the extreme end of those negotiations.”

Image by Lily Mae Martin

To have a child is to enter into a strange new set of negotiations with society, our partners, our family, ourselves. To also be an artist, it seems to me, is to be dealing with the extreme end of those negotiations, because of the self-driven nature of art and the lack of guaranteed compensation. At a personal level, asserting your need to create; to carve out the time and space that art demands; to feel confident in the validity of what you have to say–requires a special kind of drive and determination for anyone. Doubly so for mothers, whose own interests and desires are expected to be sublimated to the needs of others.

So, in my mind, endeavouring to be both artist and mother raises some of the biggest questions about how we choose to live and view the world: self versus society, partnering versus independence, feminism versus masculine, sacrifice versus self-interest, creativity versus economics… In this way, I think the experience of artist-mothers can speak to the feminist debate at a particularly subtle and sensitive level.

Kerry: Motherhood is so incredibly interesting, the ideas around it far-reaching and important. I’m thinking about the book On Immunity by Eula Biss, a vast and important sociological text, and in her acknowledgements, she thanks the mothers in her community who made her realize “how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are…”

Kerry: Motherhood is so incredibly interesting, the ideas around it far-reaching and important. I’m thinking about the book On Immunity by Eula Biss, a vast and important sociological text, and in her acknowledgements, she thanks the mothers in her community who made her realize “how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are…”

I didn’t really understand this when I first read your book, when I first became a mother—the ramifications of the ideas you’re talking about, we’re all talking about. (I certainly had no idea that motherhood would be so interesting that I’d end up editing an anthology about it too years later….)

Another interesting thing is that it’s ever in flux. What are the questions and ideas around motherhood that are preoccupying you these days?

Rachel: As you say, mothers are raising the next generation, so their actions and decisions are far-reaching and important indeed! Mothers have a unique stake in the future, and that’s why they are spearheading so many campaigns and movements around the world. In Motherhood & Creativity, writer Tara June Winch, who herself set up onethousand.org (a charity to promote female empowerment), says, “I’ll argue that most NGOs, globally are run by mothers in one way or another.”

Motherhood is a galvanising force—and one of the best things about writing The Divided Heart was that it connected me to an incredible community of mothers, who think very deeply about the way they parent but also about the world that they have brought their children into. Fathers are there too, of course. But among the families I know, while fathers are very much involved, it’s largely mothers who are still doing much of the logistical work as well as the theoretical thinking behind the parenting—and most of the worrying, sadly!

Motherhood is a galvanising force—and one of the best things about writing The Divided Heart was that it connected me to an incredible community of mothers, who think very deeply about the way they parent but also about the world that they have brought their children into. Fathers are there too, of course. But among the families I know, while fathers are very much involved, it’s largely mothers who are still doing much of the logistical work as well as the theoretical thinking behind the parenting—and most of the worrying, sadly!

Personally I have always found mothering hugely confronting; the role presses me to be a stronger, braver, more industrious person than I feel capable of being most days. And we are raising kids in unusually complex times. I’m very conscious of wanting to raise children who feel empowered in a culture that is: 1) largely driven by a consumer-capitalist ethos; and 2) facing potential catastrophe as a result. The big question for me is: how do we raise kids who are critical and creative thinkers, who will make ethical decisions, and who will treat the environment, themselves and other people with respect, when right now all they want is a PlayStation 4 for Christmas?!

I think creativity can play a big role in all of this. I love Pip Lincolne’s comment in the book: “There’s a forgiving, nurturing quality about handmade that should be applied to life. Not everything is perfect, but it was made with good intentions and there were so many little, meaningful decisions along the way. I think that mindful approach is such a good thing and an ace ethos for a family.”

Could there be a better approach to bringing up kids? I reckon Pip has it pretty sorted!

March 25, 2015

After Birth: Redux

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.