January 6, 2017

Rad Women Worldwide

Quite intentionally, I am raising my children in a house full of books, and while this has resulted in my children engaging with books a lot, best intentions don’t always lead where you’d like them to. I do have a theory that books can work by osmosis and that just being around them makes people smarter, and I cling to this belief when my oldest child passes up the incredible works of world-broadening non-fiction we have stocking our shelves in order to reread the Amulet series for the five-hundredth time. I had this vision of children sprawled on the carpet, leafing through our encyclopedia of animals, illustrated atlases or perusing the images from Sebastian Salgado’s Genesis. Sometimes I even intentionally leave these books on the floor, so as to instigate said leafing and perusing, but then the children just end up using these books as stools on which to perch while reading Amulet.

The book Rad Women Worldwide, by Kate Schatz and illustrated by Mariam Klein Stahl, might have joined this pile of books for sitting on. It was an extra Christmas gift, purchased without forethought. A good book to have around the house, I thought, particularly in these regressive times. Subtitled, “Artists and Athletes, Pirates and Punks, and Other Revolutionaries Who Shaped History,” by the creators of the brilliantly conceived American Women A-Z. It doesn’t hurt that the book’s design is awesome. I loved the idea of my girls learning about the incredible women profiled within, and understanding that their amazing accomplishments are what history is made of. We don’t even have to call it “herstory.” All this is simply the society in which we live.

Rad Women Worldwide includes women making history throughout history, but also women who are making history as I write this. And I love the idea of my children taking for granted not just that history includes women, but that history (and feminism) includes women of colour also—this is huge if I hope to raise white feminists who aren’t White Feminists (TM). I want to raise girls who see race and know race, acknowledging the role it plays in people’s lives (including their own). And I want them to know that the world and progress is powered by women who are black and brown and Asian, as well as white. I want my white children to grow up inspired by the accomplishments of women of colour—and with this book, how can they not be?

The thing about Rad Women Worldwide, though, is that it’s not just for children. It’s not only they who have gaps in their education, and the stories in this book are so fascinating that we’ve started reading them aloud. So that this isn’t a book just for sitting on, but also because I want to learn more about the women I’ve already heard of (Aung San Suu Kyi, Malala Yousafzai) and want to discover those I hadn’t heard of yet (Kalpana Chawla, the first Indian female astronaut, Junko Tabei, who was the first woman to climb Mount Everest, Fe Del Mundo from the Philippines who was the first woman admitted to the Harvard Medical School in 1936).

So we read a profile a day, Harriet and us taking alternate paragraphs, and I love the words that are entering her reading vocab: “Indigenous,” “Constitution,” “Advocacy,” “Reconciliation.” These stories are the perfect antidote to the bleakness that pervades news stories about women right now, riding the sad coattails of #ImWithHer. Inspiring, fascinating and ever-illuminating, each story affirms my faith in progress and justice just a little bit more.

December 13, 2016

Awkward Conversations

As a parent, having uncomfortable conversations with my daughter is one of my favourite things. The other day after listening to the news on the radio, she asked me, “What’s sexual assault?” And I was so grateful to be able to answer that. To be able to give her the context for these awful, disturbing ideas, rather than her getting her context from elsewhere, from less reliable sources. From the cruel world even, when she’s utterly unprepared for it. It’s the same reason I read her the Grimms with the violent endings, the nasty stepmother destined to dance eternally in shoes made of burning iron. Even though these deliverances of justice aren’t in keeping with reality, I think the fact that the world can be brutal and hard. I don’t want these things to ever come as a surprise to her. I willingly brought my daughter into the world, and along with that, I see myself as required to take responsibility for all of it, the good and the bad.

They aren’t opposing, also, the good and the bad. This is what I want to teach my daughter about the world, about its complexity “A single thing can have two realities,” is a line I wrote in my essay, “Doubleness Clarifies,” about motherhood and abortion. It’s always been a lesson I wanted her to learn. “And so one day I will tell her about what happened to me a long time ago,” I wrote about my daughter and my abortion, in this essay I wrote when my daughter was three. I was always grateful for that essay, because it meant I’d never be able to not tell her what happened to me. It would force me to take responsibility too for this part of my own story.

Last week I shared the above photo of protesters from the 1970 Abortion Caravan in Ottawa on Instagram. I spend a lot of time on Twitter raging about abortion access and perception, while my Instagram feed is all teacups in soft sunshine. I wanted to be more well-rounded in my Insta-life, so I shared the image. And later that night, Harriet was scrolling through my feed and saw the photo. “Who are they?” she asked, and so I told her about abortion.

I told her about the brave women (and men) who fought hard so that she and I could have control over our reproductive lives. I told her about how people are trying themselves in knots trying to restrict women from aborting lentil-sized fetuses. “But it’s not their lentil,” she said. “I KNOW!” I answered. And I told that when she was a lentil, she was everything. We read her stories even though she didn’t even have ears. But she was everything because we loved her already and we wanted her. In physical terms, she was almost nothing. Pregnancy is perilous at 6 weeks.

I told her about my friends who’ve had abortions later on, when everything is so much harder. About how these were heartbreaking choices, the losses of children who were desperately wanted. About how nobody has an abortion for fun. It’s always a careful choice, and sometimes not an easy one. And it’s hard to understand because one person’s lentil is someone else’s baby. But Harriet is seven and already she understands that a single thing can have two realities.

I haven’t told her yet that I had an abortion. She didn’t ask. These conversations have to be organic, I think. But I’m sure I’ll tell her soon, and when I do I’ll tell her this: “If not for my abortion, I wouldn’t have YOU, and I’m grateful everyday.”

December 4, 2016

I regret the cake

They say that over the course of a lifetime you never regret the cakes you baked, but instead the cakes you didn’t bake, although in one specific case I will make an exception—except I am also sorry for the butterfly cake I brought to a party in 2000 that was mostly paste, and the cake I over-mixed for my friend’s engagement in 2008 that had the consistency of cheese. But not this sorry.

They say that over the course of a lifetime you never regret the cakes you baked, but instead the cakes you didn’t bake, although in one specific case I will make an exception—except I am also sorry for the butterfly cake I brought to a party in 2000 that was mostly paste, and the cake I over-mixed for my friend’s engagement in 2008 that had the consistency of cheese. But not this sorry.

I regret the cake, the Hillary Clinton victory cake I baked on November 7.

“If all else fails, there will be cake,” I blogged blithely, but it turned out that the cake didn’t taste very good. When I’m really upset, I don’t have an appetite for anything, and so that sad cake hung around our kitchen getting stale and eventually I threw it in the garbage. The day after the election, I had a task that involved cutting out thirty small squares of paper and using a hole punch, and it was about all I was up to. I sat there at my kitchen table cutting and punching, and weeping as I listened to Hillary Rodham Clinton’s concession speech on the radio. I probably ate some cake, but I didn’t taste it. There was no consolation.

If I had to do it again though, I’d probably still make the cake. Partly because I’m bloody-minded. And partly too because I refuse to budge from my vision of what the world could be and what it should be. I’d rather be wrong than be wrong, if you know what I’m saying. Although I did feel guilty after the fact—I know I inspired other people to embark upon similar baking projects, and there we all were sad in our kitchens on that terrible Wednesday morning. There was so much cake, physical evidence of disappointment, and all of it was my fault.

But I’ll take the fall. I was wrong, and I’ve been wrong before, but as I said above, at least I wasn’t wrong in fundamental ways. I’ve tried very hard to resist a dynamic of winner/loser from this election, not because I don’t like losing, but instead because I don’t mind if I do lose. It doesn’t matter. You might call me a crybaby, but I’ll just look at you confused, wondering why you’re delivering such a puerile insult, and I really don’t care what you think either way. (I’m not going to run out into the street and start firing off my stockpiled ammunition either, and there is really something to that.)

“The art of losing isn’t hard to master…” It’s true. I’ve lost before, over and over again, and what I learned from these experiences is that mastering losing can mean that you can do absolutely anything. I have no fear of failure because I’ve failed over and over again, and everything turned out…fine. Often the very worst thing that can happen isn’t. There are certain things that if I lost them, my life would be fractured irrevocably, but these things are mostly people and I don’t know that anyone can master that kind of loss, although I even know some strong, incredible friends who appear to have done so, who carry on under the weight of interminable grief. So there is loss and there is loss, I mean.

The results of the election have been devastating, but I’ve resisted the idea that my/us having lost is part of the equation. No, it’s something more than that, which is what is actually lost on the simple-minded people who are gloating. Those gloating people aren’t why I was crying, but instead I was crying for everyone, for a vision of the world that’s not that I thought it was, what I hoped fervently it could be. I was wrong, and a whole lot of people proved me wrong, but I can handle that. And if necessary, I’ll be wrong over and over again. Until I’m right, because that’s how history swings.

The results of the election have been devastating, but I’ve resisted the idea that my/us having lost is part of the equation. No, it’s something more than that, which is what is actually lost on the simple-minded people who are gloating. Those gloating people aren’t why I was crying, but instead I was crying for everyone, for a vision of the world that’s not that I thought it was, what I hoped fervently it could be. I was wrong, and a whole lot of people proved me wrong, but I can handle that. And if necessary, I’ll be wrong over and over again. Until I’m right, because that’s how history swings.

It’s been a brutal month. On Thursday I finally got my ass back in gear, and started replying to hundreds of emails with apologies for being unable to anything much for this past month except stare at my computer screen in abject horror. I fell down terrible twitter rabbit holes that made me despair about everything, and to wonder about the bubble that I live in, confused and messed up by “voices obsessed with rhetorical fallacies and pedantic debating practices.” When reality starts to seem like a giant conspiracy theory in itself, it becomes hard to know what’s what, and where you stand on things when ground is ever-shifting.

What’s brought be back to earth? Books, of course. I started reading Caitlin Moran’s Moranifesto last week, and it set me straight about feminism, and class, and why I don’t want a revolution (“Personally, I’m not up for that. The kind of people who are up for mutinies and riots tend to be young men… I, however, am a forty-year-old woman with very inferior running abilities and two children… I’ve read enough history books to be resoundingly unseen on extreme politics of with the left or the right…They tend to work out badly for women and children. They tend to work out badly for everyone.) While there has been an effort to package this book as more than a collection of her columns, with a thesis and everything, it doesn’t quite work, but it doesn’t have to. Moran is terrific. “Why We Cheered in the Street When Margaret Thatcher Died.” “This is a World Formed by Abortion—It Always Has Been, And It Always Will Be.” “We Are All Migrants.” The world has gone so willy-nilly in the last year that some pieces in this collection are dated in a way that hurts my heart, but the fundamentals still stand. Last Tuesday evening I sat alone reading this book in a public place and I kept laughing aloud in a way that disturbed passersby, and that was a good thing. It was like a terribly funny person finally talking some sense back into me.

And along those lines, I picked up Luvvie Ajayi’s essay collection next, I’m Judging You: The Do-Better Manual. A book whose first section left me unmoved, but I think it was tactical, some light and easy judgement toward people who don’t wash their bras regularly or who court unemployed boys with gambling addictions who call you to pick them up at the casino because it’s raining and their only form of transport is their bicycle. Breaking the reader in for the heavy stuff—”Racism is for Assholes,” “Rape Culture is Real and it Sucks.” Powerful, amazing sensible stuff that I so desperately need to hear right now when everything seems so upside down. A Black woman writing about feminism, a Christian woman critiquing how religion is messing so much up these days, a smart woman unwilling to withhold her judgement, so she gives it and it’s glorious and we’re better for it. Consistency is overrated. The point is to be good, to ourselves and to each other. I’m about two thirds into this book, and I’m loving it, reminding me that this upside-down world is the same as it ever was, and that striving for better is the least and the most we can do.

And along those lines, I picked up Luvvie Ajayi’s essay collection next, I’m Judging You: The Do-Better Manual. A book whose first section left me unmoved, but I think it was tactical, some light and easy judgement toward people who don’t wash their bras regularly or who court unemployed boys with gambling addictions who call you to pick them up at the casino because it’s raining and their only form of transport is their bicycle. Breaking the reader in for the heavy stuff—”Racism is for Assholes,” “Rape Culture is Real and it Sucks.” Powerful, amazing sensible stuff that I so desperately need to hear right now when everything seems so upside down. A Black woman writing about feminism, a Christian woman critiquing how religion is messing so much up these days, a smart woman unwilling to withhold her judgement, so she gives it and it’s glorious and we’re better for it. Consistency is overrated. The point is to be good, to ourselves and to each other. I’m about two thirds into this book, and I’m loving it, reminding me that this upside-down world is the same as it ever was, and that striving for better is the least and the most we can do.

“But the ultimate pragmatism is to quietly note that idealism has won, time after time, in the last hundred years. Idealism has the upper hand. Idealism has some hot statistics. Idealism invented and fuelled the civil rights movement, votes for women, changes in rape laws, Equal Marriage, the Internet, IVF, organ transplants, the end of apartheid, independence in India, the Hadron Collider, Hairspray the musical, and my recent, brilliant loft conversion. Every reality we have now started with a seed-corn of idealism and impossibility—visions have to coalesce somewhere.” —Caitlin Moran

November 16, 2016

Notes

On the evening of Friday November 4th, I was walking down the street with a copy of Erin Wunker’s Notes from a Feminist Killjoy in my bag. Striding with purpose, something vital playing through my headphones, and a man on the street approached me. He was holding a clipboard, wearing a vest that identified him as a fundraiser whose job it is to get passersby to sign on in support of a charity. The kind of person I tend to smile at, shaking my head, as I keep on walking. Usually I am also herding recalcitrant small children, which makes me less of a target. But that night I was unencumbered, and although I gave no indication of wishing to engage with this person, he wouldn’t relent. Walking alongside me, asking questions, even though I was listening to music, never made eye contact, never answered him.

On the evening of Friday November 4th, I was walking down the street with a copy of Erin Wunker’s Notes from a Feminist Killjoy in my bag. Striding with purpose, something vital playing through my headphones, and a man on the street approached me. He was holding a clipboard, wearing a vest that identified him as a fundraiser whose job it is to get passersby to sign on in support of a charity. The kind of person I tend to smile at, shaking my head, as I keep on walking. Usually I am also herding recalcitrant small children, which makes me less of a target. But that night I was unencumbered, and although I gave no indication of wishing to engage with this person, he wouldn’t relent. Walking alongside me, asking questions, even though I was listening to music, never made eye contact, never answered him.

He didn’t stop and finally I had to say to him, each word delivered with such deliberateness as I waited at the intersection for the light to turn green: “I don’t want to talk to you.”

The light turned green, and I stepped into the street, and I could hear him behind me: “Oh, that’s really nice,” he was calling out to me, as though I’d refused him something he was entitled to, as though his invading my space necessitated a kind of niceness that ought to be returned.

But, No, no, no, I was thinking. I’m not having any of that.

*

There is something about notes. Notes have an irrefutability that a manifesto lacks, albeit in a shrugging-off kind of womanish way. “When I started this book, I wanted to write something unimpeachable,” writes Erin Wunker in the introduction to her Notes From a Feminist Killjoy, but her book turned out to be something very different. Or not. “Unimpeachable” is like a red rag to a bull in the realm of discourse. You’re going to go out and build this solid thing just to have someone break it. They call this “debate”. It’s logic, rhetoric. When you debate you’re not meant to get emotional, to remain at a remove, which is easier to do when you’re not personally invested. When it’s theoretical and you can examine it cooly, not getting all hysterical. Okay then, let’s talk about you policing my body, for example. About campus rape. Let’s call abortion a debate.

It’s back and forth. It gets you nowhere. Turns my actual life into a game of ping-pong. I get hysterical.

Notes, on the other hand. Wunker: “I remember that I tell my students that reading and writing are attempts at joining conversations, making new ones, and sometimes, shifting the direction of discourse.”

*

“Notes” is a way of ducking.

Also, ducking is a mechanism of survival. What is wrong with being unwilling to be a target, with refusing to play that game?

“Notes” is different game happening on a whole other level.

*

If I wanted to “impeach” Notes From a Feminist Killjoy, there would be a couple of points I’d start from. The chapter on feminist mothering, for one, which seems to be unaware or else does not to take into account the substantial body of scholarly work on this subject—Sara Ruddick, Andrea O’Reilly, my friend May Friedman, for just a start. Although the chapter poses something familiar to those of us who’ve lived it—the woman on the verge of discovery of this vast world of motherhood and feminism, the questions motherhood necessitates and the unfamiliarity of it all. The complete inapplicability of everything we’ve ever learned before to serve as solutions to our problems. This is a chapter written by an author who is still lost at sea. And there is usefulness in that kind of documentation. But yes, it might have been helpful to have some suggestion of the shore.

My other problem with the text was with the nature of the killjoy, whose moniker I’d wear with relish, actually. Particularly a feminist killjoy. That IS the kind of no-fun I most want to be. (Wunker takes her title from Sara Ahmed’s blog, feministkilljoys, which has been a tremendous discovery for me since reading her book—”joining conversations, making new ones.”)

But I kept being tripped up by the noun becoming a verb—the killjoy actively killing (patriarchal) joys. For a few reasons, one being the violence implicit. I don’t want to kill anything. And also that I have certain amount of reverence for joy. (One of my daughters’ middle name is “Joy.” The other’s middle name is “Malala,” which means sadness, so don’t think I don’t get the whole picture, but she gets to be named for a kickass feminist heroine so it all comes out even.) Joy and happiness, which Wunker writes about as a socialized and commodified product, a social imperative. “Happiness as restricted access. Happiness as a country club, a resort, an old boy’s club for certain boys only.” Happiness as an impossibility.

And yet it’s that notion, not of happiness itself but of its impossibility, that chafes me. Partly because I believe in (even insist on) a genuine happiness that need not be commodified at all—the way the afternoon sun shines right now on my cup of tea, for example. It’s about being present, eyes wide, curious and ready to receive it. It’s about the peace of a moment. Happiness is small and it is slippery, but it’s real.

There really is such thing as joy, and to refer to patriarchal violence as such a thing undermines it. Undermines the spaces we need to create for joy to exist in our personal corners of the world.

*

Of course, there has been very little joy for anyone who considers herself a feminist in the past week. (It is November 15 as I write this.) That Friday evening as I asserted myself and said, “I don’t want to talk to you,” seems like a relic of a bygone age. When we were reading (excellent, amazing) news articles with headlines like, “The Men Feminism Left Behind.” When I was thinking that progress was slow, but how far I’d come to be able to speak up and say those words to the man on the street. To not have to worry about being nice. When I was taking comfort in my daughters coming into the world on the headwinds of so much necessary, vital change.

After I crossed the street that night and left the man behind, I got on the subway and read Wunker’s chapter about rape culture. The part about her running through the woods to flee a man who’d tried to lure her into his car on a country road. I remember the details: her Birkenstocks, the wound on her foot. The sense that all of us have had of being chased, the fear. Rape as a thing and rape as a sceptre, an inevitable that we steel ourselves for. By not walking at night, for example. There is no joy here either. There is darkness illuminated by streetlights, but even there you can’t be safe.

*

Notes is a way of starting. Trying. Essai. If a manifesto is a red rag, then a note is a building block, a puzzle piece. The reader responds not by charging, but by saying, Yes and, or Yes but. She doesn’t respond by tearing the whole thing down.

I love the way the narrative thread of Wunker’s book makes its way with seeming effortlessness. There is nothing laboured about how a discussion of rape culture leads to the Jian Ghomeshi trial leads to women coming together leads to a chapter on friendship. (Which references The Babysitters Club. Yes, and!!) Why are so few of our formative texts about female friendship? “What is it about female friendship that inspires such insipid descriptors?” What are relationships between women often so fraught?

“Is it too hard to write your own narrative and witness another’s, simultaneously?”

*

As I watched the election results last Tuesday night (and felt as heartbroken as I’ve ever felt in my life, perhaps, which is saying something for how lucky I’ve been in a world that’s notoriously hard to live in) I was trying to read the book I’d been reading for a couple of days, Making Feminist Media: Third Wave Magazines on the Cusp of the Digital Age, by Elizabeth Groenveld. I started reading it because those third wave magazines (Bitch and Bust) were what taught me to call myself a feminist, made me realize that I’d been a feminist all along. I’ve always loved magazines—you know, the kind that smelled like perfume—but then one day I stumbled into the magazine rack at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore and discovered there was a kind of magazine that didn’t make me feel like less than a person. That there were things other than just a boyfriend that could make my soul complete—do you know what a revelation this was to me? It’s still shocking to consider just how much.

As I watched the election results last Tuesday night (and felt as heartbroken as I’ve ever felt in my life, perhaps, which is saying something for how lucky I’ve been in a world that’s notoriously hard to live in) I was trying to read the book I’d been reading for a couple of days, Making Feminist Media: Third Wave Magazines on the Cusp of the Digital Age, by Elizabeth Groenveld. I started reading it because those third wave magazines (Bitch and Bust) were what taught me to call myself a feminist, made me realize that I’d been a feminist all along. I’ve always loved magazines—you know, the kind that smelled like perfume—but then one day I stumbled into the magazine rack at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore and discovered there was a kind of magazine that didn’t make me feel like less than a person. That there were things other than just a boyfriend that could make my soul complete—do you know what a revelation this was to me? It’s still shocking to consider just how much.

I never noticed when I was writing them that everybody in the magazine was white. It would take me years to realize there was anything strange about that, what a departure from reality such whiteness actually is. I also recall reading letters in Bitch about whether this was a magazine for feminists or lesbians, and (I say this with shame) feeling similar consternation. I didn’t know there was such a thing as intersectionality then. I have learned a lot since I started reading these magazines a decade and a half ago.

What occurred to me though on the day after the elections as I finished reading Grovenveld’s book was the difficulty all these magazines have had in surviving—how the feminist message remains so niche. Considering this in the context of the number of white women who voted for a misogynist fascist seems sort of unremarkable. Why doesn’t feminism sell more? Thinking too about what Grovenveld writes about identity politics and how focusing on distinct groups creates a sense of community among the group’s members, but ultimately it keeps the focus too narrow for widespread change to occur. For the magazine to be sustainable, she means. (Although she writes that a magazine being short-lived is not fair as a standard of failure. The fact that it even existed at all, and was read, defies so many odds.)

On Friday morning I was walking with my friends and we were talking about that group of women who voted for a misogynist fascist, and one friend framed this too in the context of intersectionality, which I’d never properly considered. I’d been thinking about the failure of intersectionality as women break apart instead of coming together (although I understand entirely, and I get that #solidarityisforwhitewomen) but never thought about the troubling intersectionality of these white women with their allegiances to the patriarchy. No woman is a highway.

What is it that makes women go so far out of their way not to support other women? Why did so many people dislike Hillary Clinton so much. To the point of going out of their way to elect a fascist, I mean. Is it because of the lack of representation of female relationships that Wunker references? To the end of getting to the answer to that question, Sady Doyle’s Trainwreck came in for me at the library.

*

Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear…and Why is a historical and pop-cultural look at the women who’ve stirred up shit from the margins and who (as Doyle posits) may have actually been prophets but it’s just that the world wasn’t ready yet. (Billie Holiday on rape culture, anyone?)

Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear…and Why is a historical and pop-cultural look at the women who’ve stirred up shit from the margins and who (as Doyle posits) may have actually been prophets but it’s just that the world wasn’t ready yet. (Billie Holiday on rape culture, anyone?)

I needed a bit of levity these last few days, but also some more context as to how we’ve arrived here, and this book offered both. Why do we set up women to fail with impossible standards, and then decide it’s our job to punish them, to destroy them, when they do?

What the trainwreck shows us, Doyle writes, is that “in a sexist culture, being female is an illness for which there is no cure.”

*

Which bring us to here.

And no, no, no. I’m still not having any of that.

November 10, 2016

How Women’s Fiction Can Save Us All

On Tuesday night I started reading The Little Virtues, by Natalia Ginzburg (which came to my attention in Belle Boggs’ essay in The New Yorker, “The Book That Taught Me What I Want to Teach My Daughter”). Not a comfort read, exactly, although there is some of that, but then the first essay is about her years in exile from the Fascists in Italy before her husband died in prison: “Faced with the horror of his solitary death, and faced with the anguish of what preceded his death, I ask myself if this happened to us—to us, who bought oranges at Giro’s and went for walks in the snow.”

On Tuesday night I started reading The Little Virtues, by Natalia Ginzburg (which came to my attention in Belle Boggs’ essay in The New Yorker, “The Book That Taught Me What I Want to Teach My Daughter”). Not a comfort read, exactly, although there is some of that, but then the first essay is about her years in exile from the Fascists in Italy before her husband died in prison: “Faced with the horror of his solitary death, and faced with the anguish of what preceded his death, I ask myself if this happened to us—to us, who bought oranges at Giro’s and went for walks in the snow.”

There are some moments when it’s important to face things head on, and to learn from someone who has gathered wisdom from decades of experience.

Women’s fiction doesn’t usually get that much credit for helping its readers face things head-on: these books are escapes, they’re beach reads. Fluffy rather than edgy, entertainment instead of education. Women’s fiction that takes on “issues” is its own sub-genre, and there tends to be a formula as to how these stories are executed, with tidy resolutions. Faced with a tyrant being elected American President, we’re supposed to be turning to weighty French philosophers, right? Or Natalia Ginzburg (which I really do recommend). Certainly not Jodi Picoult.

What is political? I’ve been thinking about this in terms of the novel I’m writing at the moment, about two women’s friendship over decades. About my forthcoming book too, Mitzi Bytes, which is about a woman who dares to have a voice and what the consequences are—but it’s also more complicated than that, because she’s not entirely innocent in her own downfall. My character is flawed, scared, arrogant and insensitive. A lot of the book is about her relationship with other women—her friends, her sister-in-law, her mother, the other other mothers at her children’s school. And what’s the point of a story like this, I wonder, at the moment of onset of a world like that?

What is political? I’ve been thinking about this in terms of the novel I’m writing at the moment, about two women’s friendship over decades. About my forthcoming book too, Mitzi Bytes, which is about a woman who dares to have a voice and what the consequences are—but it’s also more complicated than that, because she’s not entirely innocent in her own downfall. My character is flawed, scared, arrogant and insensitive. A lot of the book is about her relationship with other women—her friends, her sister-in-law, her mother, the other other mothers at her children’s school. And what’s the point of a story like this, I wonder, at the moment of onset of a world like that?

The question of how women get along and the ways in which they don’t is fascinating to me. I suspect that every story I ever write will be about this. And I am also fascinated by how 53% of white American women voted against a strong, experienced feminist and instead for a noted misogynist. I am fascinated by the women who cheer for him exuberantly and claim that he could grope their pussies anytime. Who are these people? What planet do they live on? Could it possibly be the same one as me?

Women’s fiction tells women’s stories. Women’s fiction also sells. And it occurs to me that this genre has the best capacity of any to help us better understand each other. The authors who are writing nuanced stories about the dynamics of sisterhood are laying out a path of relations. Why are women’s friendships so intense? How come when we don’t like a woman we don’t like her so much. Why is it so challenging to see a woman making choices that are different from yours? Why is it all so personal? Why can mother/daughter relationships be so fraught?How come when we have so much in common (and when so much is at stake) we can be so vehemently opposed?

Women’s fiction tells women’s stories. Women’s fiction also sells. And it occurs to me that this genre has the best capacity of any to help us better understand each other. The authors who are writing nuanced stories about the dynamics of sisterhood are laying out a path of relations. Why are women’s friendships so intense? How come when we don’t like a woman we don’t like her so much. Why is it so challenging to see a woman making choices that are different from yours? Why is it all so personal? Why can mother/daughter relationships be so fraught?How come when we have so much in common (and when so much is at stake) we can be so vehemently opposed?

Part of it is because we’re human, of course. Human beings are complicated. This is awkward, but is in fact one of the best things about humans. While these differences are difficult to navigate, it would be terrifying if we were all the same. Who would push us to be better? How would we know what to rise above? Part of it too comes down to something I’m working out about gender and specificity—a guy in a suit is a guy in a suit, and any guy is going to see that and identify, but women have different hair colours, and different hair styles, and maybe she’s wearing a pantsuit and maybe she’s wearing a dress, and does she stay home and bake cookies or is she Diane Keaton in Baby Boom, and all these differences make it easier to find something to dislike about somebody. Unless, of course, you just happen to dislike guys in suits as a blanket rule (and lately I am thinking there is something to that).

In women’s fiction, I think, we can get to the point of figuring it out. We need authors to consider these questions and write thoughtful and nuanced stories about them (and this is happening now). We need readers too to pick up these books and reading with questions in mind, to allow themselves to be challenged by some of the ideas contained therein. I need to get a better sense of that 53% of white women and what they were voting for or against. The women who supported Clinton but did not dare to admit it beyond the confines of a secret Facebook group need to grapple with these questions too, because they bear some responsibility as well for what happened—women who won’t dare to make Thanksgiving dinner uncomfortable. White liberal women who need to (for the sake of their children, their country) rise up and flip that fucking table, and let their fathers and brothers (and sisters and mothers) know just what has been stolen from them with this election.

In women’s fiction, I think, we can get to the point of figuring it out. We need authors to consider these questions and write thoughtful and nuanced stories about them (and this is happening now). We need readers too to pick up these books and reading with questions in mind, to allow themselves to be challenged by some of the ideas contained therein. I need to get a better sense of that 53% of white women and what they were voting for or against. The women who supported Clinton but did not dare to admit it beyond the confines of a secret Facebook group need to grapple with these questions too, because they bear some responsibility as well for what happened—women who won’t dare to make Thanksgiving dinner uncomfortable. White liberal women who need to (for the sake of their children, their country) rise up and flip that fucking table, and let their fathers and brothers (and sisters and mothers) know just what has been stolen from them with this election.

And what better place to find stories of uncomfortable dinners and torrid family dynamics? Why, women’s fiction, of course. (And Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections too, which totally falls into the category.)

We need to be reading more authors of colour too to find out what’s happening at the dinner tables of families who might not necessarily look like yours. I’ve been so grateful to those who chose to market books by Brit Bennett and Angela Flournoy as mainstream fiction this past while so that their books came onto my radar. I am going to continue to actively seek out diverse voices in commercial fiction and use whatever platform I have to amplify them, and hope that other white commercial writers will do the same, for its a genre that’s as disturbingly white as any other.

We need to be reading more authors of colour too to find out what’s happening at the dinner tables of families who might not necessarily look like yours. I’ve been so grateful to those who chose to market books by Brit Bennett and Angela Flournoy as mainstream fiction this past while so that their books came onto my radar. I am going to continue to actively seek out diverse voices in commercial fiction and use whatever platform I have to amplify them, and hope that other white commercial writers will do the same, for its a genre that’s as disturbingly white as any other.

We need to support, and promote too, commercial writers who dare to be overtly political in their work, to read them as thoughtfully and generously as Roxane Gay reviewed Jodi Picoult in The New York Times. Let’s celebrate the commercial writers who are daring to take risks, as Marissa Stapley suggests in our conversation on commercial fiction. Writers need to keep striking that perfect balance between books that people are actually going to want to read, and books that give us something to think about. Books that build bridges, or at least look-out points.

The work commercial women writers are doing has always been important, but perhaps it’s never been more important than right now.

November 7, 2016

On victory, cake and my religious zeal

This is Hillary’s victory cake, fresh from the oven. Tomorrow we will celebrate and eat it when the day is through. I made it today as a gesture of faith—faith in sanity prevailing, in the goodness of democracy, and the triumph of human decency. And yes, I made a cake because tomorrow I am going to celebrate with my daughters at the fact of a woman being president of the United States.

“Just think,” I told my elder daughter yesterday. “One day you might have a daughter, and she won’t be able to believe there was ever a time when a woman had never been president.” (Read Jill Filipovic on the men feminists left behind; read Roxane Gay on voting with her head and her heart; read Filipovic’s “Women Will Be the Ones to Save America from Trump.”)

Throughout the last six months, which have been so difficult on a global scale, I’ve found myself turning to my religion a lot for comfort, my religion being: trying really really hard to be a decent human who does good things. Be the change you wish to see in the world. And a lot of my religion does indeed involve cake, and faith: bake the cake, for tomorrow we shall celebrate. And even if we aren’t celebrating, at least there will be cake. (I’m like Marie Antoinette, but only selfish instead of a tyrant.)

But we will be celebrating. My faith is strong. I am practically a zealot.

November 1, 2016

Moms who have desks

Moms who have desks is an idea that comes up several times throughout Mitzi Bytes. My character has an office on the third floor of her house, a space she struggles to justify to herself sometimes and to her family—and not just because her most vital occupation (her blog) is a secret to everybody in her life. Her friends have similar desk angst—one has put hers in a closet, but since she’d previously worked in a cubicle without a door, this represents a kind of promotion. If you squint.

The above image is a screenshot from a feature I read a few years ago about organizing your home—if I recall correctly, it quite rightly irritated readers and was subsequently removed from the feature. But it stuck with me, that dismissiveness about women’s work, about a woman’s place in her home, for its derision of household management (which is totally a job) as an occupation worthy of its own tabletop. When my character takes into account her desk—a hulking solid oak object she found on the curb years and years ago and dragged home all by herself, a relic of a life she lived a thousand years ago—she thinks of this feature. “Moms who have desks.” As though this is a sweet affectation.

I thought of this again the other night as we read Spic-and-Span: Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen, about Gilbreth—psychologist, industrial engineer, efficiency expert, mother of twelve, best-known for the Cheaper By the Dozen book and movies. She also invented the shelves in the door of your fridge and the foot-pedal trash can. Not only a mom who has a desk, but she was a mom who invented a desk. Her Gilbreth Management Desk (pictured left) was unveiled at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933: “Intended for the kitchen, the desk had a clock and, within easy reach, a radio, telephone, adding machine, typewriter, household files, reference books, schedules, and a series of pull-out charts with tips on organizing and planning household tasks.” (Info from here.)

I thought of this again the other night as we read Spic-and-Span: Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen, about Gilbreth—psychologist, industrial engineer, efficiency expert, mother of twelve, best-known for the Cheaper By the Dozen book and movies. She also invented the shelves in the door of your fridge and the foot-pedal trash can. Not only a mom who has a desk, but she was a mom who invented a desk. Her Gilbreth Management Desk (pictured left) was unveiled at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933: “Intended for the kitchen, the desk had a clock and, within easy reach, a radio, telephone, adding machine, typewriter, household files, reference books, schedules, and a series of pull-out charts with tips on organizing and planning household tasks.” (Info from here.)

Intended for the kitchen, yes, but Gilbreth did not underestimate the tasks on a mother’s or any woman’s to-do list.

Ironically, however, I don’t actually have a desk. I mean, I’ve had a few. Once upon a time I had a desk that my husband carried home for me on his bicycle, which is a form of devotion the likes of which have been rarely matched. And in another lifetime, I too worked in a closet, although it had electricity and a window—but no heating, and now that space is crowded with toddler-clothes-intended-for-hand-me-downs and boxes upon boxes of Christmas decorations. And on one hand I could feel put-out by this, by the absence of a room of my own, but I don’t feel the lack. I don’t need a desk exactly, because I’ve chosen to make the world my desk, table-tops the planet over. My kitchen table, my lap as I lie down on my bed or on the couch, or the arm of the couch on a day when I’m required to be upright. The table in the window of the coffee shop I’m sitting in right now on College Street as I wait to go pick up my daughter from Brownies…

What a desk is is permission, I think, to take yourself and your work seriously, no matter what it is you do. It can be actual (solid as oak) or metaphorical. A surface upon which to take stock, to finally begin.

October 2, 2016

I don’t care about Donald Trump.

I don’t care who Elena Ferrante is. Not one iota. Having read her books, I feel as though she’s given us everything a person might be required to—and more. Which is why I retweeted such a sentiment this morning, only to have a complete stranger respond to the conversation with a (man)admonishment: “lots of things to get angry about this morning and you settled on this…” A complete stranger whose timeline is non-stop Donald Trump. Donald Trump: who I don’t care about even more than I don’t care about Elena Ferrante.

I don’t care about Donald Trump. I don’t care about his stupid hair, or his weak-chinned son, or his parade of wives. I don’t even care about his taxes. There is nothing at all that I could learn about Donald Trump that will confirm anything about him that I don’t know already. I don’t care about his tweets. I don’t care about his Russian ties. I don’t care about his reality TV and his insecurities and his mystique or his appeal. I don’t care about his fucking stupid ball cap. When I never have to see his hideous smirk again, it won’t be a moment too soon.

I don’t care about Donald Trump, and only partly because I don’t live in America and my interest or lack of in its politics has no bearing upon what happens there. I don’t care about Donald Trump, because the same people who pontificate via their Facebook platforms about the shallowness of celebrity culture and the vapidness of teenage girls fixated on selfies are glued to his every move. I don’t care about the debates, which will teach viewers nothing remotely interesting or insightful. I don’t care about Donald Trump, because I’d rather read a novel by Elena Ferrante and also for the same reason I’d rather not read a novel Philip Roth or Martin Amis, or anyone who is determined that the purpose of literature is to “be the axe for the frozen sea within us.”

I am so fed up with maleness, Donald Trump its chief emblem. I am so fed up with nothing being as important as war, except sports, which is a microcosm of the same. I am sick of war rooms and chicanery, and heartless people who proclaim themselves heroic for “making tough decisions.” I am sick of credit being given to contemporary neanderthals for “evolving”—the rest of us did that millennia ago. I am so tired of the sexism, blatant and systemic. For the absolutely shit that women have to go through every day, whether they’re running for office or working in an office. I am tired of valid, heroic protests (a man kneeling during a national anthem, just say) being more controversial than a police officer shooting an innocent person. I am tired of this perception that a life matters more if a person who wore a uniform lived it. The body of a brilliant artist pulled out of a river, and the police officer who racistsplains it all on Facebook. I am tired of Trump and all the other blowhards in pursuit of power (Canadian Conservatives, you people who have no shame and no lows you won’t go to, that would be you) and making all the racist assholes feel pretty comfortable with their points of view in 2016, I am so absolutely tired of the people who are totally loving this train wreck of a presidential election, and feeling morally superior for their attention to it—this is politics, current events, the pursuit of “social justice.” All of you are complicit in making the world a more terrible place.

Naturally the obvious question would be that if I truly did not care about Donald Trump, why indeed have I just written an entire post about not caring about him. A question to which I reply, fervently, as much I don’t care about Donald Trump, I care so very, very much about not caring about him.

So very much that if you need me, I will be reading a giant novel.

Written by a woman.

August 25, 2016

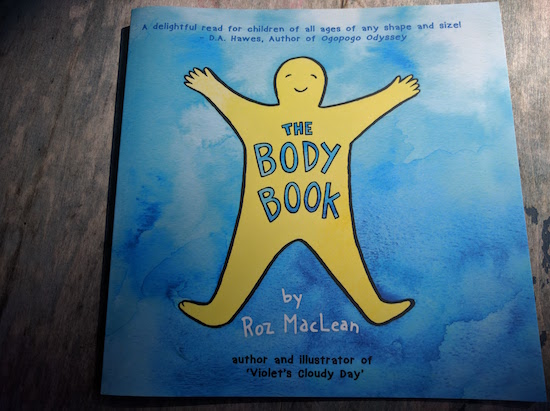

The Body Book, by Roz MacLean

If my copy of Lindy West’s Shrill hadn’t been from the library, among the countless parts I would have underlined would have included the part where she states that she’s never actually hated her body, or felt loathing toward it, but instead was just all too aware that the rest of the world thought that it didn’t conform to its standard. Which has always been my experience, for the most part (which, full disclosure, is also fairly easy for me to say, because my body has rarely deviated very radically from the standard, and let me tell you, there were some years when my body was pretty smoking’ hot [1997 and 2007 in particular were good years; maybe it’s a decennial thing, in which I’m holding out big hopes for the forthcoming annum]).

Truth: I’m still working on losing the baby weight from my second pregnancy—if by “working on losing the baby weight” you mean “eating a lot of croissants and not giving a fuck about the baby weight.”

I’ve always aspired to be quite at home in my body. When I was 17 and wrote for a teen section in our community paper, I plagiarized an article I’d read in a teen magazine about the contentment of a girl who’s eating a McDonalds hot fudge sundae—I wanted to feel that good about myself. That I had to steal the idea though is perfectly telling.

In 2001, I made my friends come with me to the nude beach at Hanlon’s Point when I stripped down to nothing and walked across a beach full of people on my way for a swim, which was truly a life-changing and empowering experience.

In 2012, I took a photograph of myself in a bathing suit and put it on the internet, which I thought was a big deal at the time (and I hadn’t even gained the baby weight!).

Last week I did the same thing again, but by now this didn’t feel remarkable. (What I wrote beside the image did though. “So glad to live in this body,” I captioned the photo, which is, in all honestly, one of the most subversive, badass things a woman can say, and what does that say about us?). And the single biggest thing that I can credit for finally attaining the self-acceptance I’ve been chasing for two decades is this one thing, or two?

I have daughters.

When I became a mother, I made several promises to myself, many of which I eventually broke (including, I will always speak kind and respectfully to my children; I will never bitch at them for reading too much [I know!—but seriously, put the book down, Harriet]; and I will never suddenly exclaim in the middle of an afternoon, “Oh my god, oh my god, all of you, now, just GO AWAY!”). But one promise I have forever stayed true to is that my children will never hear me say a negative word about my appearance. Not one. Because I think that as much as some women may dislike their appearances, all the more omnipresent is the fact that we’re kind of taught that we have to. It’s how to be a woman. Permitting yourself four almonds for a snack, and worrying about “muffin tops” and back fat. So much of it is a learned behaviour, if even by osmosis, and of course it is, because it’s everywhere.

But not in our house. There came a point when I realized our eldest was listening to every word we said and then I stopped whining, “I feel fat” and “I’m ugly!” to my husband whenever I was feeling blah (and let me tell you, other than me, there is no one involved in my personal transformation who has benefitted more than my husband, who apparently doesn’t miss my insecure neediness. Who knew?). I started delivering non-sequiturs at dinner like, “Man, I sure like my freckles,” and “I think my hair looks really pretty today” (about as naturally, at first, as I might bring up topical ideas like online porn or bullying, the kinds of talks you gotta have).

The think about fake it ’til you make it though, is that it’s kind of true. In my experience, there are only so many times you can say, “I sure love how strong my arms are” or “I really like the way I look in this dress” before you start…meaning it. Before you start actually looking for things about you to like and love, because of course it’s good for your daughters, but the thing about it that you never expected is that it’s also good for you.

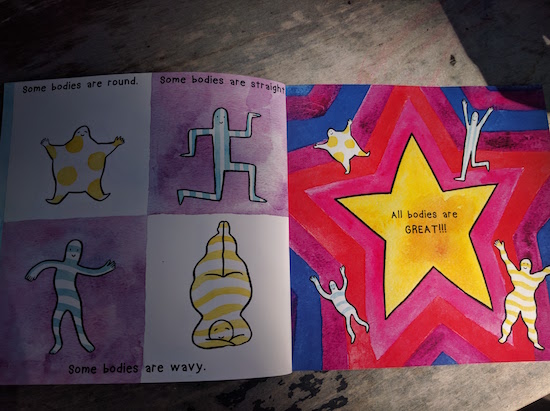

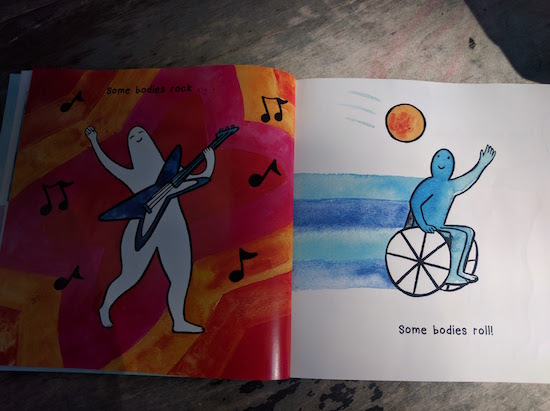

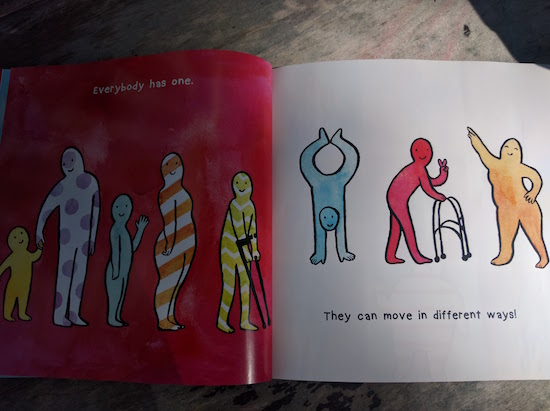

And so this is why I love Roz MacLean’s The Body Book, a simple little paperback with enormous ramifications. Because a mother is going to pick up this book for her child, and they’re both going to enjoy the story’s celebration of bodies of all kinds, shapes, sizes, and abilities: “Some bodies are round./ Some bodies are straight./ Some bodies are wavy./ All bodies are GREAT!!!” She writes about bodies that swim and play, and dance all day, and bodies that love hugs, and bodies that need space, and rocking bodies and rolling bodies, and wibbly bodies, and wobbly bodies too.

All well and good, illustrated with simple cheerful images of blobby bodies in a rainbow of colours all doing what bodies do.

The very best thing about The Body Book though, the most excellent and profound, is that every time that mother reads the book, she’s going to have to deliver the line, “I love my body. Do you love yours too?” A line that, as I’ve stated, is actually one of the bravest, most amazing things that a woman can say.

And I love that once that mother has said it enough, there is a chance she might actually mean it.

August 17, 2016

Abortion Baskin Robbins

In her essay, “When Life Gives Your Lemons,” Lindy West notes that she’d rarely think about her abortion anymore if she wasn’t driven to speak out against “zealous high school youth groupers and repulsive, birth-obsessed pastors” who win ownership of the abortion conversation by default—possibly because most other people acknowledge that abortion (and pregnancy and life in general) is messy, nuanced, intensely personal and not very well or cleverly served when batted around like a rhetorical badminton birdie. I identified with a lot of West’s essay, but not this one bit. Because the truth is that I think about my abortion all the time. It’s a matter of geography, and I can’t even help it, Abortion Baskin Robbins being case in point.

It’s a juxtaposition that amuses me, abortion with an ice cream shop. Some might be uncomfortable with the idea, but it’s the word “abortion” spoken aloud that usually troubles people, not necessarily the ice cream. Some might thing I’m being flippant, and the truth is that I actually am, and I’m still a bit high on the liberation I feel at finally being able to say that word, abortion, over and over. Even in an ice cream shop. (Can you imagine how it feels to have the point on which your adult life has hinged be an event that is meant to be literally unspeakable? Can you imagine how empowered you feel when it isn’t anymore?)

But it’s not all flippancy and irreverence—there is meaning there. This spring and summer, Abortion Baskin Robbins is where we’ve turned up as a family after my children’s Thursday night soccer games in a school playground a few blocks north. The fact is that while the last fourteen years taken me to amazing places, geographically speaking I haven’t left the neighbourhood. The sidewalks I travel in my daily life are the same ones I took when I was people I don’t even remember now, including a girl who was once so sad and relieved to obtain an abortion during the summer of 2002. So that my children’s post-soccer ice cream joint is the same place I went to with my friend immediately after my abortion all those years ago. My children order ice cream cones that turn their lips blue, and I can’t help think about the connections between my abortion and my life as a mother, which are everything. The foundations I’ve built my life upon. (Is it any wonder that I’m grateful for the freedom to design my own fate?)

It was a long time ago, distinctly not fun, and I was pretty drugged, and so it’s so surprise that I don’t remember a lot of it well. I’ve probably got some of the details wrong, and lost most of them altogether, and I cannot actually recall what it was to be the first-person protagonist of any of these events, but there are fragments to rise to the surface. The trip for ice cream for one, the advent of Abortion Baskin Robbins (although it wouldn’t be properly named for more than a decade—but what it means to be able to name these things, these pivotal landmarks in our lives). I don’t remember what I bought there, if it was a cone or a sundae or an ice cream cake. If it offered any satiation, or if it helped me feel better. I remember that my friend was with me, the friend who must have taken a day off work and travelled with me on the subway and the bus. (What an incredibly thing to do for someone—I am sure I was not sufficiently appreciative. How could I have been?) And then we went back to her house and I think we had a stack of movies, and I recall that I’d required they all be empowering feminist films. I wanted battle armour. A bunch of other friends came over and we ate indulgent snacks and watched the movies—I think that one was The Legend of Billie Jean. I was completely, unequivocally supported, and even though in my experience of accidental pregnancy I’d felt isolated and impossibly alone, after the termination I had a circle around me. It is possible that it never even occurred to me that I wouldn’t.

(“Abortion is women’s work, I guess,” writes Heidi Julavits in The Folded Clock.)

All this is on my mind because I’m reading a collection of writing about abortion, and realizing that my experience of support was not something to be taken for granted. That it makes all the difference in the world for a woman coming out the other side pretty unscathed, and not having to carry around a terrible secret shame for the rest of her days. It’s the reason why I’m able to link a medical procedure to ice cream instead of trauma. It’s why I’m able to say the word out loud now. It’s the reason I was able to get on with my life and steer it in a directly of goodness and fulfillment. I cannot even fathom what it would have been to have to go through all that alone, or ashamed. I don’t want to begin to speculate on what would have happened to me.

Update: 20 minutes after posting this, I ran into anti-abortion protestors on the street. I had five minutes to pick up my kid at daycamp, but had to stop. Again, I cannot imagine what it would be like to endure such unnecessary nonsense, to have to defend my life choices to a twenty-something twit who wouldn’t know an ovary if it punched him in the face, if I didn’t have an Abortion Baskin Robbins in my history. These people have no idea what they’re messing with. (Why do you magnify your images so much, I ask him. Because we want people to see them, he said. Doesn’t it mean something quite significant, I told him, that otherwise you’re grossly inflating the situation [quite literally] they can’t?)