March 20, 2020

Crocodile Dundee

The only thing I am properly equipped for at this time (except for keeping calm and staying home, of course) is writing about Crocodile Dundee, which I watched on Netflix two nights ago, and it was so terrible, but fascinatingly so, and also short. The strangest thing about the film is that I am sure that I was taken to see it in the cinema when I was seven, and while the movie is not inappropriate exactly, it doesn’t really seem really appropriate either. Similarly, while the movie is really short with lots of action scenes, nothing much really happens in it at all. It’s just so bad, and not just because the female lead is a journalist whose boyfriend edits the paper she works for and her dad is the owner. She’s late coming back from Australia, because she’s got a lead on a terrific story, about a guy in a remote territory who was attacked by a crocodile and survived. She meets him, and it turns out that he is very greasy, skin like leather, appears to be literally coated in dirt. So naturally, she develops sexual feelings for him, or kind of. Also, she treks through the jungle without a hat or bug spray, which I just couldn’t get over. She has a bodysuit for every occasion, as you do on a jungle trek, I suppose, and her bodysuit has a thong, which we learn when she takes off her skirt to bathe in the lagoon (where she gets attacked by a crocodile and Mick Dundee saves her).

And then she decides to invite him to come back to New York with her, because wouldn’t that make a fish out of water movie! Her boyfriend greets her at the airport, and it turns out that Mick Dundee doesn’t know how to use an escalator, and later he has the same problem with a bidet, and he doesn’t even know how to use a bed. Sue has absolutely no character development and her fundamental purpose in the film is to find Crocodile Dundee adorable in a childlike way, simultaneously sending confusing sexual signals, all the while having zero chemistry. And her boyfriend is so rude and unattractive! And the parties that she takes Mick to are totally weird and boring! And he keeps grabbing people’s genitals, and it’s supposed to be funny, but it’s horrifying. Also why does Sue have no friends?

The “that’s not a knife” scene lived up to my memory of its epicness, but everything else is terrible. In the movie’s final scene, Sue and Mick meet in a crowded subway station and to get to her, he hauls himself up to the rafters and literally walks across the crowd, stepping on people’s heads, and it’s supposed to be charming. It was not. The movie was awful, and yet somehow it was exactly what I needed.

March 17, 2020

On Being New to Handwashing

As I’ve written many times, I blog to make sense of the world—but I’m not quite ready for that yet in terms of how this crisis is unfolding, as I’m cycling through all the feelings at supersonic speed, and the ground underfoot just feels ever-shifting. We are not in a place to make sense of any this yet, but in the meantime, and in response to recent judgy internet memes, I want to write a frivolous explanation for one specific instance of poor personal hygiene.

And I’m talking handwashing, which has become all the rage these last few weeks, to the point where our hands are chapped and bleeding. Whatever it takes though to protect our health and that of others—SIGN ME UP. But yes, it’s true that obsessive handwashing is kind of a new thing for me. “I washed my hands before it was cool,” so goes the judgy meme, and I did too, I guess, at all the obvious moments, but never while singing Happy Birthday.

I have never been very squeamish about germs, which is good, because I have children, and when my daughter was two, she ate part of a cheese sandwich she found under a table in Glasgow. When I’d take my children for walks in their strollers, they liked to reach out and touch the garbage cans on the sidewalk as we strolled by. They licked subway poles, and the bottoms of shoes, and I’d read that scientific study about how picking your nose and eating it builds immunity, so I just decided to let it go.

And so washing our hands just wasn’t really a thing, unless maybe your fingernails were green, or you’d just gone to the bathroom, or had been finger painting, or digging in the dirt. Definitely after handling raw chicken, and usually before. Yes, I am gross, but “better gross than neurotic” was honestly my kind of slogan.

Of course, I’ve since gone over to the other side. Now I watch TV and see people shaking hands, touching their faces, and my heart starts palpitating. Ordering takeout and fetching the mail seems fraught. I am going to have to go out grocery shopping one of these days (we’re on Day 5 of Keep Calm and Stay Home) and the ideas honestly terrifies me. Potential contagion everywhere. I am washing my hands constantly, even though I don’t leave the house, as though lather was a kind of prayer, and maybe it is.

March 4, 2020

My Barbies Always Got Pregnant

Maybe it’s genetic? Because we were listening to our children playing Playmobil the other day, and one little plastic figure or another in their game had gotten knocked up, and my husband said, “It’s just like you!” Because my Barbies always got pregnant, always. I didn’t even really have Barbies, but I played when them at my cousin’s house, and the narrative of our game would inevitably reach the point where I’d stuff a pile of clothing under my Barbie’s voluminous blouse (my cousin’s Barbie fashions were very 1970s and a-line) and suddenly it would be A Very Special Episode. I don’t recall that my Barbie ever had a partner, because who could be bothered with Ken, who underpants were moulded to his body, so it wasn’t like that old Barenaked Ladies Song. I don’t recall either where I got the idea for this Barbie story line—it is possible I was unduly influenced by the movie Look Who’s Talking, but that movie didn’t come out until I was 10, and I think I’d been playing Pregnant Barbies for years before that. And it wasn’t even Barbies—any kind of imagination role-playing game would, for me, inevitably lead to me getting pregnant (with clothes stuffed up under my t-shirt, natch), to the point where people didn’t want to come over and play with me anymore—although it’s possible there were other reasons for that.

Other pop-cultural pregnancies that influenced me: Elyse Keaton’s shark-jumping pregnancy late in the Family Ties series (she goes into labour while wearing a brown velour track suit that I think my cousin’s Barbie had); Elizabeth McGovern’s pregnancy in the movie She’s Having a Baby, with co-star Kevin Bacon, which I never even saw, but I was obsessed with the trailer and where she said, “I stopped taking the pill”; when Martha Plimpton gets pregnant in the movie Parenthood (and perhaps that entire movie); and the Molly Ringwald vehicle For Keeps, which I am not sure I ever saw either, but I sure did read the back of the VHS tape at my corner store. And yes, Look Who’s Talking, and maybe the source of all of this is that I figured if I got pregnant, at least I’d end up with John Travolta in the end. (And Kenickie and Rizzo in Grease. Even though that was just a false alarm.)

I also spent my childhood reading newspaper articles I didn’t properly understand about stories like Baby M, and Chantal Daigle.

Anyway, it occurred to me—as I listened to my children following my imaginative footsteps, as I was going through copy edits for my brand new novel that is forthcoming in October—that my Barbies never actually quit getting pregnant, and that I just started writing their stories down in stories instead. Because my fictional characters always get pregnant too. Or they don’t—I’m currently writing a short story about a man whose wife, an online influencer, decides to monetize her infertility. In 2014, I edited an anthology of essays all about the experience of getting pregnant, or not getting pregnant, because these are the big turning points in a person’s life. A year ago I wrote about how I do love me a good fictional abortion (which is not to say that the nonfictional ones aren’t worth having, obviously) but I think I can take a step back from that and consider that it’s pregnancy in general (desired or not, realized or not) that most intrigues me from a narrative point of view. It’s why, to be frank, books about men don’t interest me that much, because men’s lives don’t offer the same possibilities, the same questions and potential for transmogrification. The hero quest? Yawn. Instead, the possibility of having your entire life railroaded (by a pregnancy or the failure to have one), not being architect of your own fortunes, so much left to chance, hope, luck. It’s in all the fairy tales, some of our oldest stories, Sleeping Beauty and Rapunzel, even the old woman who lived in a shoe.

February 21, 2020

Calm

2016 was the year in which I spent a lot of time waking up and not recognizing the world I lived in anymore, which was certainly a privileged position to be in (or emerge from), but that didn’t make it fun. “If somebody’s not safe, then none of us are safe,” was a phrase I heard that stuck with me, as violence and tyranny in faraway places crept closer and closer, as we stumbled through 2017 and I started getting massacre fatigue. I kept thinking about Syria, and all those people who’d been living regular lives up until just a few years ago, and how what separated me from those people’s experiences was mostly nothing.

To be anxious at this moment in time is certainly not to have one’s feelings be unfounded, of course. And while it’s in my nature to compare right now to other difficult periods in history (in the 1960s, everyone supposed they’d all die in a nuclear war, for example, which is the thing I remind my daughter of when she wonders if she’ll have a future because of climate change), that is not the same as saying we don’t have to do anything about what’s going on. And I’ve become especially resistant to people insisting that everything is fine, and that, moreover “there are good people on both sides” in order to justify such a position. Anyone who starts in on The Militant Left, as white nerds in stupid khaki pants take up their tiki torches and parade through the streets of major cities. Certainly, everything is not okay, and the oceans are riddled with plastic and the forests are burning.

But it somehow got to the point where every time a plane flew over my house, I supposed we were all going to die (and guys, we live under a major flight path). I got emergency weather alerts on my phone, and would have heart palpitations. Every time there was a wind gust, I’d be thinking about cyclones, and patio furniture flying off condo balconies and that poor person in the west end who was killed by a flying STAPLES sign during a storm in September 2012. It all became more than a little overwhelming.

And then it stopped, with the end of November. Like that. I wish I could tell you how it happened, but I really don’t know. (This shift did correspond with positive results from one of my various annual cancer-screening medical appointments [#Thisis40], but surely that’s not the reason I’m not afraid of the sound of airplanes anymore?) And there have been a few times since where I’ve sensed the anxiety creeping back, which has itself made me anxious, because I don’t seem to have much control over this thing, but each time the anxiety over the anxiety has proved worse than the anxiety itself, which quickly retreated and was never as enveloping as it had seemed before.

But it’s not gone. It’s there, but at a remove. I can note it, acknowledge it, and choose not to indulge it, as I lie under my covers in bed at night and hear a howling wind outside. I can make a choice to hear the wind and stay calm instead, which did not seem to be an option before.

The night of January 3, I opened my laptop and checked Twitter (I don’t have Twitter on my phone, as a kind of self-preservation) and saw that #WorldWarThree was trending after the US’s targeted killing of an Iranian military official, and instead of scrolling and scrolling in a futile search for reassurance and understanding, I closed my laptop again. In contrast, when the Russian ambassador to Turkey was assassinated in December 2016, similarly leading to hysterical tweets about Franz Ferdinand, World War, and ominous phrases like, “Here we go…,” I couldn’t close my laptop for days. But this time I had enough to perspective to consider that all of us could probably benefit from calming right down.

Similarly a week after the targeted killing, when we received the devastating news that a passenger airplane had been shot down “by accident” outside of Tehran, killing everyone on board. It was news that hit particularly close to home, as 57 Canadians were on board and many more were also en-route to Toronto, and grief hung low just like a fug, but. “I am working at channelling calm as I head into today,” I posted on Instagram that morning. It seemed particularly important for my own mental health, but also on a broader level, because it had been escalating military attacks (the opposite of calm) that had led to the tragedy in the first place.

During the past couple of weeks, our country has been (I’m not going to say GRIPPED BY, because gripped isn’t a calm word, and I also don’t think it’s particularly accurate) following the protests set up along rail lines in solidarity with people fighting against the construction of a pipeline in the Wet’suwet’en First Nation in Northern British Columbia. These rail line protests have blocked the transport of goods and also passenger trains, and yes, its all very complicated, because the Wet’suwet’en people (consistent from what I understand of all groups of people ever) have divided opinions on what exactly should be done about the protests, not to mention the pipeline itself. I really do not have a comprehensive understanding of the matters at stake—though such a lack has not stopped other people from opining—but have appreciated the government response, which some might term as measured. Or calm. Even though Twitter partisans are raging that the Prime Minister doesn’t know anything about power, and the rail companies with record profits are following through with layoffs they were already planning but blaming the blockades so they don’t have to take the heat for their actions, and it’s reminiscent of the immediate aftermath of last month’s plane crash when the very same blowhards were calling on the Prime Minister to declare Revolutionary Guard in Iran a terrorist organization. It’s all just so incredibly stupid, because none of these people know what the answer is anymore than I do. None of it’s simple, and the only way toward an answer is work, which is what’s happening now all around us, and we need to be patient. And calm.

Calm is a superpower. This is a line from Ann Douglas’s latest book which is ostensibly about parenting, but which is really more about community, and connection, building a village, and learning to be better understand and support each other. And while Douglas is indeed speaking about parenting directly when she talks about calm being a superpower (and oh my gosh, is it ever), this advice is just applicable when it spills over into everything.

Perhaps it’s the closest thing we’ve got to an answer to anything right now.

February 13, 2020

I Know What I’m Doing

There are lots of memes and online posts where somebody writes about having no idea what they’re doing, but they’re doing it anyway, pushing through, persisting, and as someone who loves the idea of process, obviously I am pretty fond of this idea. “I don’t know what I’m doing but I’m doing it anyway,” could have been the tagline for this blog throughout its many evolutions over the last twenty (20!) years, and maybe the tagline for my whole life….but I wonder if too often we (me?) are focusing too much on the first half of the idea and obfuscating the second clause. It’s the doing it anyway that’s the point, instead of the undermining of our expertise. There are undoubtedly people who know exactly what they’re doing and who don’t do anything at all, and so at least you’re not in that boat, is what I’m saying. And that it’s only by “doing it anyway” that you’re ever going to figure out what you’re doing at all, and sometimes this is even possible. Not even in the “fake it ’til you make it” way (which is also a very good technique, so I’m not trying to undermine it) but for real. “I know exactly what I’m doing,” is a thought that really does occur to me from time-to-time (albeit never about sourdough), and it’s so empowering when it happens. To feel good and confident about a thing you have made, and not even be pretending—or is this just what it feels like to be 40?

February 10, 2020

18 Ways That Having a Sourdough Starter is JUST LIKE Having a Baby

- Somebody just handed me this living thing, and its existence does not entirely make sense to me.

- Care and feeding of this living thing is a little bit overwhelming and I spend lots of time texting questions to my friend who has had a sourdough starter for six weeks longer than I have and therefore knows EVERYTHING.

- I am worried I am not to be trusted with this living thing, and keeping it alive is causing me anxiety.

- I spend evenings googling the things that confuse me in particular about the behaviour of my sourdough starter, and perusing sourdough forums to find experiences I can relate to.

- I discover sourdough forums, where opinions are strongly held and factions end up fighting amongst themselves.

- My sourdough starter is a bit weird, and I have trouble mapping my experience onto the ones that everyone else is writing about.

- There are a lot of different ideas and philosophies about care and feeding of a sourdough starter, and how a sourdough starter (and in particular a loaf) eventually turns out seems to be completely unrelated to any of these ideas.

- Every loaf you make will be completely different from all the others.

- People have their sourdough starter ideas, and get a bit tetchy when you decide to raise yours differently.

- They’re worried you’re not feeding yours enough, or that you’re feeding it too much.

- I can’t stop sniffing it.

- Heated online debates can be found between those who discard their starter every time they feed and those who don’t.

- I start to think my sourdough starter is perhaps a little exceptional.

- My sourdough starter keeps me up at night—or at least, I am unable to go to bed until I’ve gone downstairs to check on it just one more time.

- I have to plan my days around it, not only the feedings, but baking a loaf of bread is a 24 hour process.

- I start to realize that it doesn’t actually matter what I do with my sourdough starter, or rather than I can follow my instincts and just do what feels right.

- I learn that I can google anything about my sourdough starter, and find an article online to justify what I believe to be true not based on any scientific information whatsoever, but instead my gut feelings about sourdough starters.

- With my sourdough starter, I can bake everything I baked without it, but just with more labour and less convenience. And somehow, mysteriously, sometimes it even seems worth the trouble.

January 27, 2020

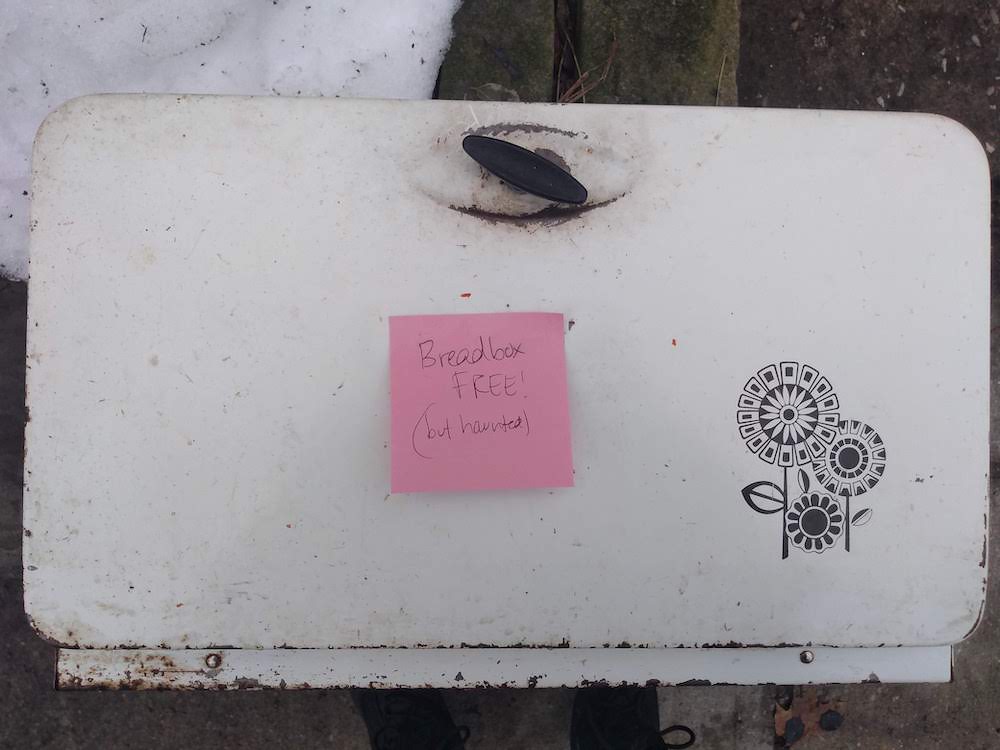

Free. But Haunted.

Farewell to our garage-sale acquired breadbox, which has been part of our family for the last decade. And never actually had bread in it very often, but was mostly used as a storage cupboard for odds and ends, and crackers, and coffee filters. And whose most salient feature was its tendency to have its door fall open just after something had been placed on the counter in front of it—last week, I lost a Pyrex bowl of egg-whites. (The bowl, mercifully, survived.) Several wine glasses being used by visiting friends also met their demise in such a fashion, and caused considerable embarrassment for all involved. I took to taping the breadbox shut when we had people over, which worked, but it still managed to catch us unaware. A poltergeist? (Or an ineffective bolt? But that’s boring…) And then yesterday, or next-door neighbour brought us over her breadbox, which is of a similar vintage (albeit without those delightful flowers). They’ve given up gluten and just had their kitchen remodelled, so the breadbox was redundant, so they passed it on, and now ours is the redundant one. We’ve put it out on the curb, but with a warning post-it. There are have been no takers. YET.

January 23, 2020

Ten Years

I had some strange feelings about reflecting on the 2010s, mostly because I didn’t. There was a meme going around Instagram stories on New Year’s Eve in which we were supposed to list a highlight from each year, and I even tried to post it, but couldn’t figure out how to get the text to fit, which maybe means that the 2010s were the decade in which I stopped being technologically savvy.

But also, the years all blend together, and so much stayed the same. The decade before was much more filled with upheaval and revolution (they were my 20s after all) but in the 2010s were where the pieces started to fit. I stopped having babies, I began to have something like a career, I finally started publishing books, I made some wonderful new friendships, and maintained old ones. It’s been good, but the decade itself, its distinction, just seems particularly arbitrary. Like—even more than a decade should.

Or do I only think that because when the decade started, I was sitting in the very same place that I’m sitting right now?

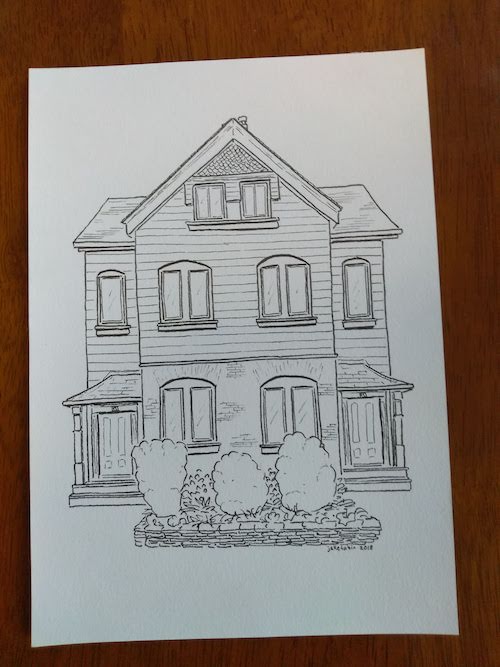

Okay. not the exact same place. (We finally bought a new couch, remember?) But the same address, our apartment, which we moved into twelve years ago this April, the longest I’ve ever lived anywhere. I moved in as half of a young married couple, and now I’ve got two kids and I’m forty, and have been married almost 15 years. The little kids who lived next door moved out and went to university, and then moved back in again, although it didn’t do me much good when they did, because now they’re too old to babysit. But, as the middle section of To the Lighthouse, so astutely put it: Time Passes.

Imagining our own story as told from the perspective of the house as Woolf does in her novel (except with less war and death). The people coming and going, coats and jackets hung up on hooks and taken down again, early morning alarm clocks and dinners, and house guests, and holidays, and the quiet weeks where we’ve all gone away, and coming home again, an explosion of luggage, and the babies arriving, and late nights with the lights on while the world sleeps, and the babies grow, and all the books that come in and those that go back out again (returned to the library, or left on the garden walls for any takers), and the birthday parties, play dates, first day of schools, pencilled lines in the door-frame measuring from small to tall, and boots and shoes and sandals in a pile at the door, and the triumphs and disappointments, throughout anxiety and contentment, and these walls have contained it all. Even as spare rooms turned into nurseries and cribs turned into bunk-beds, and empty space turned into clutter—Lego, puzzles, and play-doh—and that ring on the carpet from where I put down a teapot and it melted. How places seem to hold us, even more than time does, and how a single place can hold so much, and so can a life.

November 3, 2019

Neither Useful, Nor Interesting

Oh, yet another blog post that begins with me talking about something I heard when I was listening to a podcast. The Mom Rage Podcast, no less—am I predictable yet? This one was about vaccines (it was so good!), featuring a conversation with medical anthropologist Samantha Gottlieb about the HPV vaccine and “vaccine-hesitant communities.” She spoke about how many people are put off by doctors’ refusal to entertain questions about vaccines at all, which only serves to underline skepticism. When the facts are that vaccines can cause risks, that vaccine injuries and reactions do happen. They happen on a disproportionately tiny scale, with risks minute. It’s more dangerous to get in the car and drive down the road, and we all do that all the time, but still. Doctors don’t want to admit it. It complicates the narrative, and complicating the narrative of vaccination is perilous, literally life and death.

Of course, I like complicated narratives. To complicate the narrative is to get as close as we can to something called truth. I don’t want to live in an echo chamber, a bubble. I relish conversations with my economist friend about the virtues of capitalism; I appreciate the activists who’ve open my eyes to the violent reality of racism; my morning routine is basically putting on shoes, but I’ve got big respect for people for whom make-up is a form of personal expression. On Twitter, I used to actually follow the person whose booking at the Toronto Public Library has created such controversy over the last few weeks, because her take on sex-work complicated what so many of the other feminists in my feed were talking about, and I found that complicatedness useful and interesting… until it wasn’t. I unfollowed this person when she started writing online attacks on the grieving father of a dead teenaged girl. When I realized this “journalist” (whose platform is her own website, which she likes to call “Canada’s leading feminist website” [according to whom?]) relishes attention more than any kind of truth, and had figured out that courting controversy was the fastest way to get there (and solicit donations). When I realized she was more invested in dogma and ideology than the feminists whose thinking (and actual lived experiences) she purports to oppose and complicate. This person is neither useful, nor interesting. She is sensationalist, and purely disingenuous. She is the anti-vaxxer of gender politics. She is not “just asking questions.”

I think there is room for questions and nuance in conversations about gender. Unlike the speaker who was provided space at the Toronto Library, I think that none of this is simple. I wish that the City Librarian had listened to so many smart and respected voices calling on her to cancel the speaker’s booking—the milquetoast mayor called her on it, for heaven’s sake. And no, these people weren’t “bullying the library.” You can’t bully a library. This is nonsense. But I also know that people too are complicated like their issues are, and there are many of them (myself among them) who don’t like being told what to do, to have demands made of them, who double down instead of considering the opposite. We put a lot of truck in unapologeticness in feminism, for better and for worse. I don’t think that we should be boycotting the library, because for so many people, especially marginalized ones, the library is their most accessible cultural institution. Because the library belongs to all of us. Because the people who have the least are the people that lose the most, and I don’t really know what the end-game is of a library boycott, especially now that the event is done and dusted. Though I commend all the people who’ve taken a stance and I do think it’s been hugely worthwhile—the turnout to the protest on Tuesday evening was an incredibly show of solidarity, and the issue has led to all kinds of conversations, which are necessary as we ask questions in generous and thoughtful ways, and figure things out as a society—a process that is far more useful and interesting than anything the speaker might have said on any platform. (This is the work, people. We’re doing it. Even if, or maybe especially if, you’ll only doing it all in your head.)

I do know what it’s like to have my body be the site of a debate. I’ve stood on the sidewalk holding a sign listening to men argue over the semantics of abortion, as to the precise point where the procedure should or should not be permitted, and I can tell you that it’s dehumanizing, insulting, ridiculous, and neither useful nor interesting. And so I have an understanding of where trans people are coming from when they refuse to entertain questions, conversations or debate about their bodies and their identities. When the field of debate is your lived reality, listening to people arguing in abstract terms and citing outlying circumstances as emblematic of the issue at hand—for anti-choicers, it’s all about the case of a particular doctor and abortion provider who was convicted of murdering infants, same as how the anti-trans crew is always going on about aestheticians and waxing, as though these are the actual goal posts and such things are happening every day—is exasperating, traumatic, and a gigantic waste of everyone’s time.

I think there is room for questions and nuance in conversations about gender, because we live in a world where there are no absolutes, but I am sure that insisting on those conversations at this precise moment is not the most pressing thing we’ve got on the go. That democracy and freedom hang in the balance, as so many others might put it in their letters to the editor. I think back to the vaccine analogy, and the distrust and violent suspicion at the heart of the anti-vaccine movement, which is not so far apart from that of anti-trans activists, really. In both cases, there is an over-estimation of vulnerability, and a convenient disregard for those who are actually vulnerable after all.

Of course, there are conversations that need to be had, questions that need to be answered, but not like this, not by this person. As with the vaccine conversation, the harms—here, it’s increased violence against and vilification of an already vulnerable population—really do outweigh the benefit, which is mainly the privileged and smug self-assurance of living in a society where any idiot gets to spout her rubbish in a public building. And if such self-assurance is our guiding principle, instead of listening to, learning from, and taking care of each other, then what does it say about us?

October 30, 2019

It’s Not About the Vision Board

I want to go back to Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, the parts about scams and delusions. That we exist in a moment where people are trying to sell us their 5 simple steps to becoming millionaires, or having body confidence, or achieving career success. That the only difference between you and that superstar you emulate is something corny like, “She dared to dream, and then she did it.” I have to confess to a mighty aversion to vision boards, especially since the images are usually cut out from magazine advertisements. Do I really want my vision to be borrowed from an ad for Hyundai? What are the limits to empowerment by hashtag?

And yet. A thing I’ve learned in the last few years, during this year in particular, is that we have more power than we realize. The point, of course, is just to use it, and certainly confidence is a factor. I turned 40 this year and what this new decade has delivered me is the confidence to realize I really do have something—skills, knowledge, experience and insight—to bring to the table. After a decade and more of not taking myself too seriously (because people who do can be insufferable) I’ve learned the value of doing so—while not being insufferable, I hope.

But it’s not about the vision board. It’s not even about “daring to dream big.” Instead, it’s about looking at the world head on and figuring out what needs doing. Asking “What if?” and daring to follow through. It’s about the doing, not the dreaming.

I note this example all the time, but it’s emblematic of many other things I’ve achieved on a larger scale: when my neighbours had a baby, I brought them a loaf of banana bread. And in doing so, I made our street, this world, a place where things like that can happen. A small thing, but I don’t discount the value of small things. I think they’re everything.

Anyone who attends a protest makes a world where people care about things. Anyone who reaches out to someone in need makes a world where people care about people.

The foundation is an understanding that you matter, and therefore the things you do will matter. And then you’ve got to do the things, which is where, of course, the work comes in.