April 21, 2016

Light and darkness, dancing together

This morning I dropped Iris off at playschool, and noticed pussy willows in a jar on the counter, which took me back to a scary time we went through through just over three years ago now. It was a time in which I learned that it was possible to navigate life even in the presence of one’s deepest fears, and also that doing so sometimes required errands such as an excursion with shopping list consisting only of a bouquet of pussy willows and a tub of chocolate ice cream. I remember that with the pussy willows, I finally began to feel better, and I think I was thinking of A Swiftly Tilting Planet at the time, but I didn’t pick it off the shelf to get the reference.

This morning I dropped Iris off at playschool, and noticed pussy willows in a jar on the counter, which took me back to a scary time we went through through just over three years ago now. It was a time in which I learned that it was possible to navigate life even in the presence of one’s deepest fears, and also that doing so sometimes required errands such as an excursion with shopping list consisting only of a bouquet of pussy willows and a tub of chocolate ice cream. I remember that with the pussy willows, I finally began to feel better, and I think I was thinking of A Swiftly Tilting Planet at the time, but I didn’t pick it off the shelf to get the reference.

But yesterday morning I was walking to school with my seven-year-old neighbour who’s currently in the middle of A Wrinkle in Time and has the other books in the series before her, and I told her how much A Swiftly Tilting Planet still means to me as an adult. It was the book I picked up in September 2001, after two planes flew into buildings and we wondered if the world as we knew it was entirely gone. I remember the comfort it brought me, the comfort it always has.

But yesterday morning I was walking to school with my seven-year-old neighbour who’s currently in the middle of A Wrinkle in Time and has the other books in the series before her, and I told her how much A Swiftly Tilting Planet still means to me as an adult. It was the book I picked up in September 2001, after two planes flew into buildings and we wondered if the world as we knew it was entirely gone. I remember the comfort it brought me, the comfort it always has.

Mrs. Murry said, “I remember my mother telling me about one spring, many years ago now, when relations between the United States and the Soviet Union were so tense that all the experts predicted nuclear war before the summer was over. They weren’t alarmists or pessimists it was a considered, sober judgement. And Mother said that she walked along the lane wondering if the pussy willows would ever bud again. After that, she waited each spring for the pussy willows, remembering and never took their budding for granted again.

I took it down off the shelf this morning to find the pussy willows paragraph, and realize that I absolutely have to reread this book again. And I considered how fundamental it might have been in cementing my understanding of the cosmos, the world.

Darkness was, and darkness was good. As was light. Light and darkness dancing together, born together, born of each other, neither preceding, neither following, both fully being in joyful rhythm.

April 18, 2016

How books talk to each other

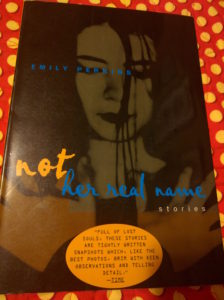

Tonight I was inspired by Sarah’s #ShortStoryaDay post to pick up “Not Her Real Name,” by Emily Perkins, from her short story collection of the same title. I’d first read the collection when I interviewed Emily Perkins in 2008, when Novel About My Wife came out. In her post, Sarah notes that she was surprised to reread this story and discover that two characters share a name with her daughter, and surmises that it was was with this story that she first fell for the name. She quotes a couple of lines from the story: “—Imagine a couple both called Thea, says Thea. —Isn’t it awful? One of the hazards of same-sex relationships I suppose.”

Tonight I was inspired by Sarah’s #ShortStoryaDay post to pick up “Not Her Real Name,” by Emily Perkins, from her short story collection of the same title. I’d first read the collection when I interviewed Emily Perkins in 2008, when Novel About My Wife came out. In her post, Sarah notes that she was surprised to reread this story and discover that two characters share a name with her daughter, and surmises that it was was with this story that she first fell for the name. She quotes a couple of lines from the story: “—Imagine a couple both called Thea, says Thea. —Isn’t it awful? One of the hazards of same-sex relationships I suppose.”

Now right now I’m reading a book called The Name Therapist, by Duana Taha, which is so much fun and absolutely fascinating and I can’t wait to tell you all about it. And perhaps I should have seen it coming, going from such a non-fiction book about names and how they define their bearers to a story called “Not Her Real Name” that I might encounter uncanny connections. And while I didn’t encounter either of my own daughters in this story, what I did find was really kind of strange.

I read the beginning of the story, the part about the two Theas, and then went back to The Name Therapist, in which Taha writes about the possibilities of same-name couples in same-sex relationships and how this idea fascinates her as a name enthusiast. And then there was a bit about a guy named Marc who orders coffee at Starbucks and gives his name as “Marc with a C,” which comes back on his cup labelled, “Carc”. Going back to “Not Her Real Name” then to find another Marc drinking coffee:

“Marc with a c. Cody’s seen it written down by the telephone… Marc. Marc. There’s something disturbing about the name. Like Jon without an h. Or Shayne with a y. Marc. Spelt backwards, it makes cram. A real word. This makes it seem like code. Code for what? Cram, cram. Trying to break the Code. OK, so her own name is enough of a liability. She shouldn’t laugh at other people’s. But Marc—its like biting tinfoil.”

Cody’s own name is referred to in connection the Jack Kerouac novel, Visions of Cody, which she’s never read, she says, and I haven’t read it either. I’m still a bit confused by the story’s title and what it means exactly, trying to break that code. And maybe this is the point. Earlier in the story, Cody’s thinking about a guy called Francis. “You always thought, Francis, rhymes with answers. Which it doesn’t, really. But you’d change the s of answers to be soft like his name.”

And isn’t all that so weird? I am really not so singular but I suspect that I am the only person in the world who is reading The Name Therapist and “Not Her Real Name” concurrently, two works that speak to each other so clearly, asking questions with answers echoing back. A book that came out the other day with a short story collection that was published twenty years ago by an author on the other side of the world—and they are connected in ways their authors never even fathomed. And this is why I love books and literature so much, that it’s all a code, quite beyond us and quite unbreakable. And the infinite possibilities of these connections too, how books upon books can talk to each other, the libraries of the world abuzz with these private conversations.

October 12, 2015

My grandmother’s china

“I have your grandmother’s china for you,” her mother said. “She took good care of it.”

I highlighted this line from a story in Kelli Deeth’s The Other Side of Youth when I read it, the china emblematic of all the ways in which the lives of women my age have failed to progress in the manner that previous generations might have foreseen. All these boxes of china wrapped up in paper and boxed up in basements, and it means nothing now. I grew up in a house with a china cabinet, is what I mean, and it is very unlikely that I will ever have such an item myself, let alone a place to stand it.

Which is not to say that the domestic has no hold, that we don’t give any value to stuff. My Pyrex fixation certainly speaks to that (and I realize now that since the photo in the link was taken, I’ve acquired a set of turquoise Cinderella bowls, and also put a halt on all non-essential Pyrex acquisitions to keep things from getting too out of control). But what I don’t need is a massive collection of dishes and cups to be hauled out on special occasions, just the same way that I don’t need a parlour for afternoon callers. What I like about Pyrex is its usefulness, and then it occurs to me that there is a similar way around the grandmother’s china as well—what if I actually used it?

I have no recollection of ever seeing this china before—I didn’t pay attention to things like plates as a child, particularly if they were patterned with wildflowers. It is also possible that my grandmother didn’t set the table quite so formally when I was coming to visit. Although I do know my own mother’s wedding china intimately. I have no wedding china, but I have a vast collection of cracked and chipped dinner plates that it’s starting to seem shameful to feed my children from, and so I asked my mother if perhaps I could take a look at my grandmother’s china. If we could use them for everyday. Would that be more or less troubling, I wondered, than the plates remaining boxed up until the end of days, or else given away to a consignment store (where I would have totally bought them if I’d happened upon them)?

And so we took them, and now they’re here, unpacked in the kitchen. Some of them need cleaning—the gravy boat is still stained from some dinner more than a decade ago. But for the most part, the plates and cups are in excellent condition. Plates of various sizes, 10 of one, 8 of another, 11 side plates, 11 saucers and 9 tea cups. I wonder what they started with? Only 2 soup bowls—what happened to the rest of them? Or was soup more an intimate course, something best suited to a couple?

Predictably, I’m now a bit obsessed with my grandmother’s china. Who knew? Spode China in the cowslip pattern with a chelsea wicker design. There turns out to be a busy online marketplace for fervid Spode collectors, and now I’m lusting after Spode eggcups and a teapot. I also admire the buttercup pattern (seen here). The former curator of the Spode Museum Trust blogs about all things Spode here (and this is why I love blogs so: there is almost nothing under the sun that has not been blogged about yet). Spode was founded by Josiah Spode in 1770 in Stoke-On-Trent—Josiah Spode was almost an exact contemporary of another pottery-maker called Josiah but instead of a Spode he was a Wedgewood.

We spent this morning at the museum, which re-enlivened my delight in the thingness of things, and it occurs to me how much of my boredom with and dismissal of my grandmother’s things has to do with the idea that this is baggage, something to be carried and put somewhere. (My grandmother never ever put her china in the dishwasher, my mother tells me. We don’t have a dishwasher, so we will quite easily be able to continue in the same tradition.) But with the idea that these things could be used rather than put up on a shelf to be dusted—it changes everything. The best part about things in museums is what they tell us about ordinary life, and so it seems fitting that my grandmother’s china should become part of our ordinary life as well.

Which ensures, I suppose, that each piece will be eventually get broken and never be passed down to anybody, leaving nothing for us to be known by, our ordinary life an enigma to those who come after us, should they even care to wonder. A paradox—the Pompeii exhibit is case in point; does it matter if your frescoes are preserved if you’re dead? But I wonder if it isn’t better to simply live in the moment after all. From a person’s point of view, I mean, if not from that of an archivist.

October 8, 2015

Really Fun DIY Autumn Craft

A few trees on our street have gone all autumnal, and while the world is not yet awash in golden and orange, the few trees that have turned already have got us in an autumn spirit. Iris had fun playing peek-a-boo with some of them on her way home from school today, and we’re glad she was not picked up by the Ministry of Flagrant Racism and Canadian Values for daring to hide her face no matter how patriotic her covering.

A few trees on our street have gone all autumnal, and while the world is not yet awash in golden and orange, the few trees that have turned already have got us in an autumn spirit. Iris had fun playing peek-a-boo with some of them on her way home from school today, and we’re glad she was not picked up by the Ministry of Flagrant Racism and Canadian Values for daring to hide her face no matter how patriotic her covering.

(Halloween is coming. If our government is still in office then, what are they going to do?)

And so we were inspired to partake in an autumn craft this evening for our weekly Fun Night, which is a dinner-hour activity that allows us to hang out and play together for a little while, instead of the rush-rush-rushing that is our regular weeknight routine. I’ve included step-by-step instructions below so you can play along too!

- See a link to a DIY Autumn Leaf Bunting tutorial posted on Facebook, and because you have a thing for bunting, actually consider doing it. Even though you hate doing crafts. The site it’s from is called The Artful Parent, but you’re more of an abstract artful parent, if you’re remotely artful, which you’re not.

- Gather leaves on the walk home from school. Feel smug and sanctimonious, anticipating the excellent time you’re going to be spending with your family and anticipate the reactions you’ll receive when you post your DIY Bunting on Facebook. Contemplate making strands upon strands of the stuff, and bringing them to Thanksgiving gatherings all weekend long so that people will admire your creativity and quirky bunting ways.

- Feel extra wonderful because you even let your kids pick up leaves that were kind of gross and had spots on them. Because it’s about them, really. And my, what a terrific childhood you’re providing them with…

- Buy store-brand wax paper at the grocery store.

- And now it’s time! You’ve already made cranberry brie chicken pizza for dinner that made the children cry (although this was before they tried it; they conceded it was delicious in the end) and so you’re on a roll.

- Press the leaves between two pieces of wax paper. The child who is still upset about the pizza gets upset again because she wants matching colours for each piece of bunting, but you want to mix it up like a rainbow. You’re really fucking insistent about this.

- (Read through the instructions for the bunting at The Artful Parent and realize that the Artful Parent actually made HER DIY autumn bunting while her child was at school.)

- Your husband pulls out the iron. Your children have never seen one. They marvel at this shiny and new piece of technology.

- He begins to iron. It should take a few minutes, the instructions say, for something to happen. Nothing happens. So he turns up the temperature. He starts to iron like no one has ever ironed before. Eventually you realize he is about to iron a hole right through your kitchen table. The leaves are burnt to a crisp. The wax still hasn’t melted. The leaves aren’t pretty anymore.

- This is the point when you storm off and start googling “Why won’t my wax paper melt?” This doesn’t actually seem to be something that happens to many people. You get sucked into a hole of websites about weird ways to preserve leaves and really stupid things that people do with them. You wonder what the point of anything is. You are suffering from bunting grief. It’s terrible.

- This is the least fun Fun Night on record.

- Back in the kitchen, however, your husband has saved the day. He’s poured out glue and everybody’s slapping the non-burnt leaves onto paper. “But what’s the point of this?” you ask him. “What’s the point of bunting?” is his retort, which is blasphemous, but still. And gluing leaves onto paper looks like of fun, so you join in.

- The night is saved by your husband’s excellent improvisational skills. And red wine.

September 29, 2015

Sir John’s Table, by Lindy Mechefske

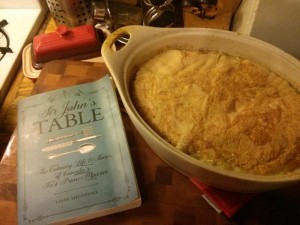

I could never be a food blogger for all kinds of reasons, one of which is that all my pots and serving dishes are indelibly stained and my kitchen is old and grubby (and poorly lit). The other important reason is that I tend to interpret recipes as general guidelines instead of instructions, but in the case of the new book, Sir John’s Table, by Lindy Mechefske, this turned out to be an advantage. It meant I was unafraid to take on the recipe for Sir John A’s Pudding from a cookbook from the 1880s, a recipe named in honour of the first Prime Minister of Canada, whose instructions included “size of an egg” for butter portioning, no word on what vessel to cook it in, and vague baking instructions as follows: “Bake in oven for a few minutes.”

I could never be a food blogger for all kinds of reasons, one of which is that all my pots and serving dishes are indelibly stained and my kitchen is old and grubby (and poorly lit). The other important reason is that I tend to interpret recipes as general guidelines instead of instructions, but in the case of the new book, Sir John’s Table, by Lindy Mechefske, this turned out to be an advantage. It meant I was unafraid to take on the recipe for Sir John A’s Pudding from a cookbook from the 1880s, a recipe named in honour of the first Prime Minister of Canada, whose instructions included “size of an egg” for butter portioning, no word on what vessel to cook it in, and vague baking instructions as follows: “Bake in oven for a few minutes.”

We really weren’t sure. “This is an experiment,” I kept telling my family, and then asking them, “Isn’t living with me a glorious adventure?” No one answered. They were all a bit irritated that our main course had been roast cauliflower. “I bet none of your friends are having pudding tonight in honour of Canada’s first Prime Minister,” I told Harriet. She looked at me funny: “Mom, do we have any ice cream?”

Sir John A’s Pudding is from Dora’s Cook Book, by Dora E. Fairfield, published in 1888—one known copy is still publicly available. It is a bread pudding, the bottom made with bread crumbs, egg yolks and lots of milk. Spread on top are stiff egg whites and sugar. I baked the whole thing in the oven for much longer than a few minutes (though I can’t remember how long now—I am as bad as Dora). When it came out of the oven, the topping was nicely browned but the pudding still seemed a little gloopy (“But gloopy means delicious, right?” I asked. Nobody cheered.) However once it had been resting for a little while the pudding was set, and now it was finally time to dish it up and assess the damage.

Sir John A’s Pudding is from Dora’s Cook Book, by Dora E. Fairfield, published in 1888—one known copy is still publicly available. It is a bread pudding, the bottom made with bread crumbs, egg yolks and lots of milk. Spread on top are stiff egg whites and sugar. I baked the whole thing in the oven for much longer than a few minutes (though I can’t remember how long now—I am as bad as Dora). When it came out of the oven, the topping was nicely browned but the pudding still seemed a little gloopy (“But gloopy means delicious, right?” I asked. Nobody cheered.) However once it had been resting for a little while the pudding was set, and now it was finally time to dish it up and assess the damage.

Guess what: it was totally divine. And everyone conceded that living with me was an adventure after all, a most delicious one. I did my I’m always right dance. I always mostly am.

Though not, admittedly, with my immediate assessment of Mechefske’s book. Sir John’s Table: A Culinary Life and Times of Canada’s First Prime Minister as a concept did not seem at first compelling to me, but then I opened it up and started reading. And what I found was an engaging, light and fun and informative text. So engaging, yes, that it led me to attempt archaic heritage recipes, plus the book is also a really interesting biography of Canada’s first Prime Minister.

Since we’re going all Full Disclosure in this post, I will reveal to you that I’ve not watched any political debates during this current federal election. As these debates fail the Bechtel Test on every discernible level, are intellectually stupefying AND we don’t have TV, I’ve felt more comfortable getting my political information from newspapers instead. There is something about the absence of women’s voices and the general feeling that anything concerning women’s experiences is mere frippery that renders most politics (and political biographies) null and void to me. It’s grown-ups acting out playground games, and taking themselves far too seriously. It’s just inherently uninteresting.

Since we’re going all Full Disclosure in this post, I will reveal to you that I’ve not watched any political debates during this current federal election. As these debates fail the Bechtel Test on every discernible level, are intellectually stupefying AND we don’t have TV, I’ve felt more comfortable getting my political information from newspapers instead. There is something about the absence of women’s voices and the general feeling that anything concerning women’s experiences is mere frippery that renders most politics (and political biographies) null and void to me. It’s grown-ups acting out playground games, and taking themselves far too seriously. It’s just inherently uninteresting.

Which is not to say that political biographies must necessarily contain a recipe for bread pudding, or that the domestic is anymore inherently a female purlieu, but it certainly was in the 19th century. Which means that “culinary life and times” of Sir John A. Macdonald is going to give special attention to the women in his life and the personal and political roles they played: his mother, his wives, his lifelong friend who was also a pub owner. We learn about the food (bannock!) his mother brought to feed her family on the long voyage from Scotland to Canada. Also about Macdonald’s favourite childhood desserts, how traditional British foods were adapted to North America, wedding cakes from the 1860s, mourning rituals (after the death of his first wife), how the picnics at which he made his famous stump speeches would have been catered (by Mrs. Beeton, at least), and just how a roast duck dinner managed to save the Dominion after all.

For a light book, Mechefske manages to be rigorous about colonial atrocities, juxtaposing a lavish Toronto dinner with Metis and First Nations people starving on the plains at the same time. Her story of the triumph of Sir John A’s railroad also includes a legacy of racism and exploitation of the Chinese workers who built it. She manages to balance her portrayal of the generous and charismatic Macdonald with the dark side of his legacy—also his own propensity for problems with drink: “He joined the Temperance Society again,” is a sentence that pops up more than once.

My one criticism is that the recipes have not been adapted for modern cooks, and so are more a curiosity than something the reader can use. Although there is value too in these heritage recipes reprinted as they were, for what they tell us about how 19th century cooks did their work, how ingredients, measurements and cooking methods were different, and also the peculiar stylistic quirks of their writers. And my own experience certainly shows (who knew?!) that the intrepid 21st century cook can have success with these recipes all the same.

September 16, 2015

A ride in the bucket

I’m something of a pathological truth-teller, which is a line I stole from Lauren Groff’s new novel, Fates and Furies, the book I’m reading right now. The interesting thing about that line being that the character described has a more ambiguous relationship to truth than the speaker supposes. Which is always the way. Truth is fudgy. I think I only have such a strong affinity for the principles of truth because lies are so easy, the slipperiest slope—and then anything one says ceases to have meaning, and then what is the point?

I’m something of a pathological truth-teller, which is a line I stole from Lauren Groff’s new novel, Fates and Furies, the book I’m reading right now. The interesting thing about that line being that the character described has a more ambiguous relationship to truth than the speaker supposes. Which is always the way. Truth is fudgy. I think I only have such a strong affinity for the principles of truth because lies are so easy, the slipperiest slope—and then anything one says ceases to have meaning, and then what is the point?

It’s true though I’m often willing to forsake a bit of truth for the sake of a story. Which is why I wouldn’t be surprised at all to have made up the whole thing, the story of my friend Britt and I driving down a country road outside Peterborough during the summer of 2000. How there was a hydro truck pulled over by the same of the road, a crew working on a Sunday. (At the time, I don’t think I knew the song, “Wichita Lineman”, or else I would have been humming it.) We pulled up alongside, and somehow had the nerve to roll down our window.

“Could we have a ride in your bucket?” I asked.

And I’ll never forget the so-perfect response: “I can’t think of a reason why not,” the crewman said.

And he even meant it.

And so the crewmen paused their work for a moment and gave us each a chance to put on a hardhat and take a trip up in the bucket. Violating more health and safety policies than I can dream up, though I was 21 at the time and didn’t think in those terms. Still though, we knew it was amazing. We took pictures. That vivid blue sky, the wispy clouds.

If not for the photo, I really wouldn’t believe it. I’m not even sure I really remember it happened. That ride in the bucket seems more like a figment. A figment of reality, if there exists such a thing. “I can’t think of a reason why not,” that crewman said—has there ever been anybody else with so limited an imagination? And yet. Perhaps he was dealing with a surfeit, head in the clouds literally and otherwise.

And I mention this story here now because for the past few weeks, I’ve been stuck in the past, working on a story whose roots are autobiographical. All this spurred on by my husband’s application for Canadian citizenship, and how I was rooting around in boxes to unearth his university degree (which confirms his competency in English). I found my diary from my final year of university, a diary that begins on September 14 2001 and is written by a girl who was dazzled and devastated by the world at once. And I found the scrapbooks I so painstakingly compiled back in those years, determined to preserve every single moment. Not yet understanding then that there are so many moments, if we’re lucky, more moments than ever could fit in a storage locker full of scrapbooks. Not understanding then either that I mightn’t want to hold onto everything forever. That there would be so much I’d want to let go.

When we moved back to Canada ten years ago, I got rid of a whole bunch of stuff. Diaries, scrapbooks, yearbooks, tossed out in black plastic bin bags. There wasn’t room for all of it. Who wants to go through life with so much baggage? But I didn’t get rid of all of it. Enough to fill a couple of boxes, from the years that were most monumental. So there would be gaps, big gaps, but I don’t regret it now. I don’t regret the bits I kept either, which become more and more precious all the time. But so too are the gaps, which allow me tremendous freedom both as a writer and as a human being. To let stuff go, to be allowed to forget, but also to fill those gaps with other things—creation.

To go for a ride in the bucket, I mean, whether it happened or not.

- If Creative Nonfiction is your thing, check out Amanda Leduc’s series this month on The Puritan’s Blog. She writes about Lucy Grealy and chutzpah, see Julia Zarankin on birdwatching and the pursuit of the strange, and Liz Harmer on writing without rules.

August 19, 2015

In the continuing story of our garden planter

In the continuing story of our community garden planter, it appears that fairies have suddenly and mysteriously set up shop there.

July 24, 2015

If you need me, I will be in the hammock.

Farewell, my friends. I will see you in a few weeks. And until then, I leave you this image of an avocado that has been partially eaten by a squirrel. I am impressed by the precision of how the top was sliced off, and the intricate details in the marks in the flesh left behind by tooth and claw.

(It is not often that one gets to use that expression literally. Hope this is the first and last occurrence of such a thing for me for some time.)

July 21, 2015

Unfathomable Doorknobs

Tonight my roommate from first year university, who I haven’t seen in fifteen years, walked past me as I stood in front of my house. It turns out she lives around the corner. It also turned out that she was holding a doorknob, because it had just fallen off her door, so she couldn’t get into her house. And it turned out that I was standing outside of her house with a box of tools, because we’d just finished lowering the seat on Harriet’s new bike. So we went over to see if we could help—we don’t know how to fix broken doorknobs either but the tools were something. And they were, because Stuart got the door open with a pair of pliers.

And afterwards, we reflected on that. What would you think if you were watching a movie, say, about somebody who is walking down the street holding a doorknob. And their salvation would turn out to be their roommate from nearly twenty years ago who just happens to be standing on the sidewalk holding a pair of pliers? How unlikely would that plot point seem?

For sheer unfathomability, fiction’s got nothing on the world.

June 21, 2015

Where books go to die

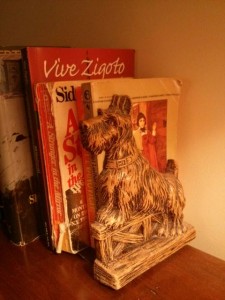

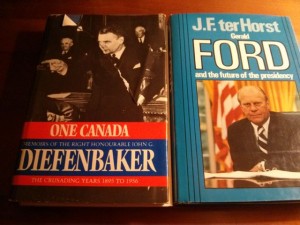

In monumental news, we spent a night away from our children this weekend for the first time in three years on the occasion of our 10th anniversary. They stayed with my mom while we embarked upon a getaway to a nearby resort with an unpretentious rustic feel. We had a wonderful time and it was not so rustic and unpretentious that I didn’t get to drink wine a jacuzzi tub, but the bookishness was extraordinary in its awfulness. There were books everywhere, and it was like they’d cleared out the dregs of every church basement book sale ever. There was a book called How to Get Things Cheap in Toronto that was published in 1977. I was pleased to find a Sidney Sheldon paperback in our room, because he was one of my formative novelists. So many hideous hardbacks. We also had two books by a novelist called Susan Howatch whose garish dust-jackets intrigued me, and I might have read them if not for the must and that I was happily away with The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson and How You Were Born by Kate Cayley (which is so very good). I was also impressed by the Scottish Terrier bookends. And I’m not even kidding.

In monumental news, we spent a night away from our children this weekend for the first time in three years on the occasion of our 10th anniversary. They stayed with my mom while we embarked upon a getaway to a nearby resort with an unpretentious rustic feel. We had a wonderful time and it was not so rustic and unpretentious that I didn’t get to drink wine a jacuzzi tub, but the bookishness was extraordinary in its awfulness. There were books everywhere, and it was like they’d cleared out the dregs of every church basement book sale ever. There was a book called How to Get Things Cheap in Toronto that was published in 1977. I was pleased to find a Sidney Sheldon paperback in our room, because he was one of my formative novelists. So many hideous hardbacks. We also had two books by a novelist called Susan Howatch whose garish dust-jackets intrigued me, and I might have read them if not for the must and that I was happily away with The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson and How You Were Born by Kate Cayley (which is so very good). I was also impressed by the Scottish Terrier bookends. And I’m not even kidding.

I’m really not. Not being snarky either. I love book collections like this, shelves packed with books that almost nobody wants to read. Where else in the world are you going to find a John Diefenbaker memoir beside a book called Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency? There’s nowhere else in the world anymore where such books belong. They’re kind of there for the decor really, but so unpretentiously, attractively faded like the armchairs. Somebody’s fancy, perhaps, but probably not. And I love that nobody even cares about that. I love how far such a collection would force you to read outside the lines, were you to arrive there otherwise bookless. And I think we’ve completely found the place where old books go to die, but it’s such a nice place. What an afterlife. Today’s literary wunderkinds could only hope for such a fate.

I’m really not. Not being snarky either. I love book collections like this, shelves packed with books that almost nobody wants to read. Where else in the world are you going to find a John Diefenbaker memoir beside a book called Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency? There’s nowhere else in the world anymore where such books belong. They’re kind of there for the decor really, but so unpretentiously, attractively faded like the armchairs. Somebody’s fancy, perhaps, but probably not. And I love that nobody even cares about that. I love how far such a collection would force you to read outside the lines, were you to arrive there otherwise bookless. And I think we’ve completely found the place where old books go to die, but it’s such a nice place. What an afterlife. Today’s literary wunderkinds could only hope for such a fate.