April 24, 2019

The Myriad Nature of Maternal Grief

Everything I know about infertility, I’ve come to understand through the analogy of abortion, which is not the opposite of infertility—though some people might have you imagine so. For your information, adoption and miscarriage are not the opposite of abortion either, as the many people who’ve had both abortions and miscarriages can definitely attest, and those women who’ve experienced adoption too. (And pay attention here, to the challenge of going beyond a single story in women’s experiences—a theme. To an insistence in our rhetoric on either/or, and maybe neither if you’re lucky, but never both.)

While I’ve not experienced infertility, I have had an abortion, which means that I’ve spent a lot of the last seventeen years thinking about reproductive choice (which delivered me the rest of my life, after all, so I spend a lot of time saying thank you). And in this thinking it occurred to me that such notions of choice must necessarily include women who want to be pregnant but aren’t, women I feel solidarity with because both experiences (wanting to be pregnant when you’re not and not wanting to be pregnant when you are) have feelings of grief and such abject despair at their core. And similarly do abortion and infertility attract the wrath of patriarchal forces, because there is nothing our society likes less than a woman who exercises agency over her destiny, who refuses to be a passive vessel.

(An additional commonality I’d never considered until reading Alexandra Kimball’s book is that abhorring abortion and dismissing the trauma of infertility both require diminishing the physical labour required to be pregnant and also that to become pregnant through reproductive technology. Abortion and infertility treatments are both considered, by those who don’t know any better, as a matter of simple “convenience,” equivocating women’s labour with, just say, a breakfast sandwich from Starbucks.)

And so Alexandra Kimball’s The Seed: Infertility is a Feminist Issue was always going to one of the books I’ve most been looking forward to this spring. (The first time I read Kimball’s work was a 2015 essay on miscarriage, which was also about her abortion, and I am always interested when abortion/miscarriage/infertility are part of the same conversation; and note: they were also all part of the conversation in the anthology I edited in 2014, The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood).

But I will admit that while I was looking forward to The Seed, its thesis (that feminism has failed infertile women) made me uncomfortable—and certainly it’s even supposed to, and it’s provocative. But what I mean is that I didn’t start reading the book completely on board, and I felt its central premise would possibly be a bit overstated. (This is kind of like when you’re white, and a racialized person tells you about their experience of racism, and you suppose they’re just being a bit sensitive.)

But it was by about page 50 and her analysis of The Handmaid’s Tale and infertility in pop culture (after the chapter on infertile women as monstrous in myth and folklore, beginning with a Babylonian epic from 18th century BC, right up to witchcraft trials just a couple of hundred years ago) that Kimball had me convinced that she was not just being sensitive. After discussing pop culture infertility in films like Fatal Attraction and The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (infertile women literally destroying the everywoman’s life) she turns to The Handmaid’s Tale, and concludes that while it is “unequivocally, a feminist text…in its world, female barrenness is not only…threatening…disgusting… it is outright oppressive, a necessary engine for patriarchy itself.”

Kimball’s analysis from here is about the tension within feminism toward motherhood in general: “an idea of motherhood as conscription into patriarchy remained central to feminist theory and action.” And how feminism’s emphasis on CONTROL in terms of reproduction left little space for those women whose experiences were beyond their control—she quotes Linda Layne on the monumental Our Bodies, Ourselves, which included miscarriage and infertility in a separate (and unillustrated) chapter at end of the book.

And who exactly gets to be in control of their reproductive lives was quite specific from the start in feminist circles—racism and classism have always played a role in this. So that even now, the experiences of racialized, queer and poor people are alienated from conversations about fertility, which itself is alienated from conversations within feminism anyway. Kimball shows numerous examples of people in general and feminists in particular being much more concerned with and disturbed by ideas about people resolving their infertility than the problem of infertility itself.

And why is it so easy for our rhetoric to remain so unconcerned about the experience of the infertile woman? “They ignore the grief,” writes Kimball, who notes that she has never felt as objectified as she did when she was infertile. “It’s difficult to see [an infertile woman] as anything other than a curiosity of capitalism, akin to people who undergo cosmetic surgery.” She writes about “the existential clusterfuck of this trauma,” how the tragedy of infertility is that resolution always seems just close enough at hand to be worth pursuing. “It’s less of a biological impulse than a narrative one, a need for coherence and sense.”

And here, Kimball begins to see the possibilities of sisterhood, of solidarity, for she finds it with a friend who a trans woman whose own experiences have been very different but who understands the extent of Kimball’s grief in a way that few other people do. (Kimball also points out that Trans-Exclusionary-Radical-Feminists find women pursuing fertility as challenging to their politics as they do trans women.) She further identifies with the the artworks of Catherine Opie and Frieda Kahlo, how they portray bodily labour and grief. “I looked at Opie’s portrait series and Kahlo’s miscarriage works frequently when I was struggling, not so much because they mirrored my own experience or made me feel less lonely, but because I was heartened by what I felt was the complexity of their stories… They demonstrate the myriad nature of maternal grief.”

That myriad nature is explored in the essay anthology Through, Not Around: Stories of Infertility and Pregnancy Loss, edited by Allison McDonald Ace, Ariel Ng Bourbonnais and Caroline Starr, a work that challenges “the single narrative” that Kimball complicates and writes against in her cultural analysis. In Through, Not Around, the political is made personal again with 22 stories of infertility, miscarriage and stillbirth, mostly by women, but with a handful by men. Each writer is telling a story that is far from uncommon, but which was until recently taboo (and even remains so in many cultures). As Kimball writes, society is made uncomfortable by evidence of the effort and labour of motherhood, would prefer it to remain hidden so we can continue to believe it is natural, essential.

My only critique of this collection is the lack of contributor bios, because it would be interesting to see what a range of backgrounds these writers are coming from. (Although I try to think of reasons why contributor bios might be avoided here, and I can think of some answers. What happens when we let the stories speak for themselves?) My sense is that these writers come from a fairly broad spectrum of experience (although, for reasons Kimball has illuminated, racialized, queer and poor women are in the minority here, as they are in conversations about fertility in general) and that most of them are not professional writers. (The anthology was born of the online community The 16 Percent.) And so I was impressed by how excellently written most of these essays were, how they made stories out of experiences that defy the conventions of narrative at every turn. (There is a reason you rarely read a novel where someone ends up having five miscarriages.)

The grief that Kimball writes about is evident in these essays, which are stories of strength and resilience under sometimes unrelenting pressure. The point indeed is getting through, which requires action instead of passiveness. But also questions of when to try a different path forward, when to stop, and all the surprising diversions that happen along the way. Women’s lives, we read in these essays, are fraught and brutal and hard and knit with tragedy, but are also unfailingly interesting.

There are so many ways to be a woman, and to become a mother, or to be infertile, even. I’m grateful to both these books for complicating the narrative in the very best way.

February 27, 2019

Happy Parents, Happy Kids, by Ann Douglas

Early on in my career in motherhood, friends would recommend Ann Douglas’s parenting books to me on the basis that she wasn’t an ideologue. “She recognizes that there’s not just one way to do things,” I remember people explaining, because she recognized that there was not just one kind of child, or one one of family, or just one simple way to make a baby fall asleep at night. It’s a kind of pragmatism that can be rare in the parental guidance industry, and which has endeared her to a generation of readers looking for advice applicable for the world we live in as opposed to an ideal one. (Douglas’s most recent book before her latest was Parenting Through the Storm, advice for parents whose children are living with mental illness.)

Her new release is Happy Parents, Happy Kids, built on the premise that in order to make positive change in family life and the life of a child, a parent should start with herself, with her own wellbeing. A suggestion that is more important than it has ever been, perhaps, because parenthood itself has never been harder. Fashioned into a verb, made into a competitive sport on display with social media, complicated by differing philosophies and an insistence that the stakes are high for everything. Because what does the future hold? Douglas’s first chapter is called “Parenting in an Age of Anxiety,” and she goes on to illuminate how parents are challenged by questions of work/life balance, why it’s easy to always feel distracted, and how it’s too easy to lose focus on the parts of having children that are wonderful and rewarding.

Her advice on avoiding distracted parenting is really terrific (the only social media I have on my phone is Instagram, but since reading Happy Parents… I have removed the app from my phone’s main screen and turned off notifications, and my life is better for it), and she has similar suggestions, backed up with research, for connecting with your children, with your partner, for figuring out what is important to you and what your priorities are in your family life, for living with stress and hardship, overcoming past trauma, choosing calm over “stressed,” the benefits of being your authentic self as a parent, and how to resist a goal-oriented approach to being a parent: “Parenting is endlessly inefficient—and that’s okay.” Implicit in every part of this book is an understanding that families come in all shapes and sizes, with a wide variety of challenges and every kind of normal. There is a lot to work with here, and not all of it is applicable to my life at the moment, but I can foresee moments where all of it might be. This is the kind of book that would be good to keep close at hand, to dip in and out of, because you know (as the book knows) that the only sure thing have having children is that everything is changing all the time.

While “Be the change you want to see in the world” (or “Be the happy you want to see in your family”) is worthwhile and really practical advice, however, it’s only the beginning of the story, and what I love about Happy Parents, Happy Kids is that Douglas knows that. “Recognize that many of the problems that we are grappling with as parents are too big to solve on our own,” she writes in the book’s first chapter. “Systemic problems require systemic solutions, after all. So look for opportunities to join forces with other people who share your desire to create a world that’s kinder and friendlier to parents and kids.” She couples her individual-based approach to self-improvement with an awareness that society itself also needs to change, and that part of the reason that having children can be so overwhelming is because the system is stacked against us. And it’s only when we join forces and work together that things can begin to change.

The book’s final section is all about the necessity of building a village—we featured an excerpt on 49thShelf last month about the challenges and opportunities of online community. And this chapter sums up what underlines the entire book—that we can only do this all together. (I’ve also been signed up for Douglas’s newsletter, The Villager, for the last few months, with her thoughts and ideas about creating community and finding common group in an ever-shifting world, and I love every instalment.)

She writes, “The issues we’re grasping with are so much bigger than any of us, which makes them all the more challenging to resolve. The fact, it’s going to take all of us pulling together to make the situation significantly better by making changes at the personal, political, and cultural level. It may start with you, but it can’t end with you…” It’s about building a better world for the people we’re raising, and raising the kind of people that world needs.

December 5, 2014

There comes a time…

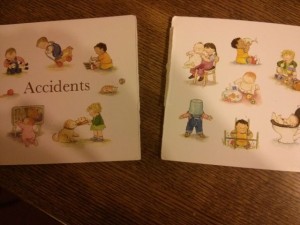

There comes a time in every family’s life when their copy of Janet and Alan Ahlberg’s The Baby’s Catalogue needs replacing. “Uh oh,” said Iris, pointing to where the book had split in two, on the “Accidents” page, no less. Though we’d seen it coming—this was the book I took care to always have in my bag when Harriet was a baby, so that when Iris was born, the spine was already shredded, and she took great pleasure in furthering the damage herself. Until the whole thing had come to pieces.

There comes a time in every family’s life when their copy of Janet and Alan Ahlberg’s The Baby’s Catalogue needs replacing. “Uh oh,” said Iris, pointing to where the book had split in two, on the “Accidents” page, no less. Though we’d seen it coming—this was the book I took care to always have in my bag when Harriet was a baby, so that when Iris was born, the spine was already shredded, and she took great pleasure in furthering the damage herself. Until the whole thing had come to pieces.

It’s a turning point, and we’ve been encountering a lot of these lately. Iris turns 18 months old exactly today, and I’d forgotten what a huge turning point this age is. Her words are coming fast (and often furious): car, and truck, and yuck, and cheese, and banana, and please, and Mommy and Daddy and Hatty, and her grandmothers’ names, and shoes, and book, and most curiously of all is “hockey”. We have no idea where she learned that one. She loves cats and dogs and babies. I take her to the library baby program, where she ignores all programming and instead walks around the circle tickling the other babies’ feet.

She sees the whole world as a series of climbable objects, and while her compulsive climbing instills fear in all those who love her, it’s true that she rarely ever falls. She knows the right techniques for capturing out attention: teetering on tabletops, screaming in quiet restaurants, and placing tiny objects inside her mouth with a defiant gleam in her eye. She gives excellent hugs, is a champion napper, has her teeth coming in in all the wrong order, and usually tries to give gentle touches instead of hitting and biting (though she doesn’t always succeed). She gets less bald with every passing day. She is at that age at which sitting at the table for more than three minutes at a time is impossible, so she comes and and goes. She just recently learned to jump. We adore her, and are blown away by how smart she is and her insistence on doing everything herself—well, even. But we’re never having another child, because our children seem to get increasingly Iris-ish with every one, and an Iris who out-Iris’d Iris might kill us. So we’re just content to love this one madly.

She sees the whole world as a series of climbable objects, and while her compulsive climbing instills fear in all those who love her, it’s true that she rarely ever falls. She knows the right techniques for capturing out attention: teetering on tabletops, screaming in quiet restaurants, and placing tiny objects inside her mouth with a defiant gleam in her eye. She gives excellent hugs, is a champion napper, has her teeth coming in in all the wrong order, and usually tries to give gentle touches instead of hitting and biting (though she doesn’t always succeed). She gets less bald with every passing day. She is at that age at which sitting at the table for more than three minutes at a time is impossible, so she comes and and goes. She just recently learned to jump. We adore her, and are blown away by how smart she is and her insistence on doing everything herself—well, even. But we’re never having another child, because our children seem to get increasingly Iris-ish with every one, and an Iris who out-Iris’d Iris might kill us. So we’re just content to love this one madly.

A nd then there is her very patient sister, who turned 5 and a half last week (which is 66 months old, for those of you keeping count). She continues to be excellent with just the right amount of naughtiness that we’re sure she’s a real child. She likes school and watching her learn to read is so exciting (and it’s also so exciting to see how useful Mo Willems’ Elephant and Piggie books are in this process. We’ve enjoyed these books for years, and that such good books can also be the best reading tools is amazing). We’re reading Tom’s Midnight Garden at bedtime now, which is exciting because there’s a literary Harriet in it, and also because it’s the second book I read right after she was born, a time I was thinking about last night as Tom and his Uncle discussed there not being just one time but instead all different kinds of time (and his Aunt pointing out that it all leads to indigestion—it’s such a good book!). Harriet has reached this marvellous age where she wants to be helpful, and she actually is. I like her so very much, and adore her company. It’s not a lie when I tell her that picking her up at kindergarten is the very best part of my day. (Well, after bedtime, of course).

nd then there is her very patient sister, who turned 5 and a half last week (which is 66 months old, for those of you keeping count). She continues to be excellent with just the right amount of naughtiness that we’re sure she’s a real child. She likes school and watching her learn to read is so exciting (and it’s also so exciting to see how useful Mo Willems’ Elephant and Piggie books are in this process. We’ve enjoyed these books for years, and that such good books can also be the best reading tools is amazing). We’re reading Tom’s Midnight Garden at bedtime now, which is exciting because there’s a literary Harriet in it, and also because it’s the second book I read right after she was born, a time I was thinking about last night as Tom and his Uncle discussed there not being just one time but instead all different kinds of time (and his Aunt pointing out that it all leads to indigestion—it’s such a good book!). Harriet has reached this marvellous age where she wants to be helpful, and she actually is. I like her so very much, and adore her company. It’s not a lie when I tell her that picking her up at kindergarten is the very best part of my day. (Well, after bedtime, of course).

Technically, now that Iris is 18 months old, there’s no resident baby at our house anymore (though I don’t believe this, of course, and Iris’s baldness is permitting the illusion to be sustained). Just because we’re running low on babies though doesn’t mean we don’t still need a copy of The Baby’s Catalogue, so we bought another one, a pristine edition that is sure to get a bit battered, but probably not as battered as its predecessor. This wonderful book is full of the ordinary moments—all the incidents and accidents—of ordinary family life, and it’s such a part of ours.

Technically, now that Iris is 18 months old, there’s no resident baby at our house anymore (though I don’t believe this, of course, and Iris’s baldness is permitting the illusion to be sustained). Just because we’re running low on babies though doesn’t mean we don’t still need a copy of The Baby’s Catalogue, so we bought another one, a pristine edition that is sure to get a bit battered, but probably not as battered as its predecessor. This wonderful book is full of the ordinary moments—all the incidents and accidents—of ordinary family life, and it’s such a part of ours.

I hope it always will be.

September 21, 2014

The Mongoose Diaries by Erin Noteboom

Erin Bow is the celebrated author of two children’s novels, Plain Kate and Sorrow’s Knot (as well as a physicist and poet), though the detail that intrigued me when I recently encountered her bio was that she’d also authored “a memoir that no one read.” I have sympathy for such memoirs, plus I am obstinate, so I sought out the book and discovered it was The Mongoose Diaries: Excerpts from a mother’s first year, which is up my alley, but only kind of, because I like to suppose I’m past new motherhood memoirs. But the best such memoirs are not just to be read in the moment, and The Mongoose Diaries (which Bow published under her maiden name, Erin Noteboom) is such a volume. It’s a beautiful, unsentimental and complicated depiction of life with a new baby, all the awful bound up with a pummelling love that is often more pummel than love.

Erin Bow is the celebrated author of two children’s novels, Plain Kate and Sorrow’s Knot (as well as a physicist and poet), though the detail that intrigued me when I recently encountered her bio was that she’d also authored “a memoir that no one read.” I have sympathy for such memoirs, plus I am obstinate, so I sought out the book and discovered it was The Mongoose Diaries: Excerpts from a mother’s first year, which is up my alley, but only kind of, because I like to suppose I’m past new motherhood memoirs. But the best such memoirs are not just to be read in the moment, and The Mongoose Diaries (which Bow published under her maiden name, Erin Noteboom) is such a volume. It’s a beautiful, unsentimental and complicated depiction of life with a new baby, all the awful bound up with a pummelling love that is often more pummel than love.

Noteboom’s depiction is complicated because life is—it is implied that her pregnancy has not come easily; she suffers from a painful and serious health condition; and midway through her pregnancy, she faces the devastating loss of her beloved sister, who drowns while on vacation in Mexico. And so her feelings about the impending birth of her first child are mixed up with sadness, fear and mourning, yet oddly apart from these as well (except for her painful insight into her own mother’s loss once her daughter is born and she knows the enormity of what it is to love one’s own child).

The book moves from the beginning of Noteboom’s pregnancy to her daughter’s first birthday, the reflections written as short diary entries that move between the ups and downs (and hilarity and despair) of new parenthood as easily as the hours do. What I found most interesting was Noteboom’s critique and resistance to the idea of the necessity of a mother’s self-sacrifice—as though it’s some sort of consolation that it will hurt her more than it hurts the baby, for example, when she returns to work when “the mongoose” is three months old. It’s refreshing to read a new mom memoir from the point of view of someone with a job as well, mixing up the whole experience—gross stains on pretty blouses, pumping at the office, having to feign a functioning brain on so little sleep. And yes, the guilt, though Noteboom kicks back at the guilt with all the force she can muster, (mostly) confident in the choices she’s made for her family.

The book is sweet and funny, sad and lovely, the diary entries interspersed with perfect poetry. As someone who plans to never ever have a baby ever again, The Mongoose Diaries made me so sad and glad about this at once, and also brought back memories of those tender early days in which I held the pieces of my shattered life, and had to put them back together. It reminded me of Anne Enright’s Making Babies, one of my favourite mothering memoirs, one of those rare pieces of literature which show that motherhood is not simply “a sort of journey you could send dispatches home.” But I am glad these writers do.

I am pleased too by the glimpse the memoir provides into Erin Noteboom’s creative life. The first year of motherhood is usually not an abundantly creative time for anyone, but she notes here and there the fairy tale she’s working on, a curious book about a talking cat. A book that would come to be Plain Kate, which won the TD Canadian Children’s Literature Award in 2011. Demonstrating that motherhood can indeed be part of the threshold for creative fulfillment and success, that it’s not necessarily the end of the story.

**Note: Iris is obsessed with this book. She walks around the house holding it, perfectly sized for her 15 month old hands. “Baby,” she says. I was reading it on Friday while trying to get her to go down for her nap, and had to hide it under a pillow because she would not lie down until I’d given it to her. She also chews on it. Sorry, Library.

March 5, 2014

It Was Not What I Expected by Val Teal

We’ve had The Little Woman Wanted Noise out of the library, a picture book by Val Teal and illustrated by Robert Lawson, recently reissued by New York Review Books. Lawson is notable as the illustrator of The Story of Ferdinand and Mr. Popper’s Penguins, though it was Val Teal’s biography that most intrigued me. “In addition to her stories for children,” it reads, “Teal also wrote a memoir of motherhood, It Was Not What I Expected.”

We’ve had The Little Woman Wanted Noise out of the library, a picture book by Val Teal and illustrated by Robert Lawson, recently reissued by New York Review Books. Lawson is notable as the illustrator of The Story of Ferdinand and Mr. Popper’s Penguins, though it was Val Teal’s biography that most intrigued me. “In addition to her stories for children,” it reads, “Teal also wrote a memoir of motherhood, It Was Not What I Expected.”

It Was Not What I Expected is described in this 1948 review as “[s]teering away from sentimentality… a vivacious, gaily turned account of modern parenthood.” I liked the sound of that, as well as any parenting memoir by the author of The Women Wanted Noise, who in her dedication thanks her own three sons, “whose noise inspires the little woman.” The book isn’t easy to come by, long out of print and not held by local libraries, but used copies are available on Abebooks (though that I bought the cheapest I regret now, because it came without a dust jacket).

I had some ideas of what an account of modern parenthood published in 1948 might read like. I had these ideas because a long time ago I’d read Dream Babies: Childcare Advice from John Locke to Gina Ford by Christina Hardyment, which is where I first encountered the idea of babies being aired from apartment buildings in cages. It is also where it was first made clear to me that childcare advice (and “parenting philosophies,” baby fads and gadgets, and dictums everyone from Ferber to Sears) is a complete load of bollocks, and that we ought to cleanse our minds of most of it, except for reasons involving amusement or historical interest. The more things change, the more they stay the same, which is both a cliche, and also Hardyment’s thesis and in this context, such a revelation.

I had some ideas of what an account of modern parenthood published in 1948 might read like. I had these ideas because a long time ago I’d read Dream Babies: Childcare Advice from John Locke to Gina Ford by Christina Hardyment, which is where I first encountered the idea of babies being aired from apartment buildings in cages. It is also where it was first made clear to me that childcare advice (and “parenting philosophies,” baby fads and gadgets, and dictums everyone from Ferber to Sears) is a complete load of bollocks, and that we ought to cleanse our minds of most of it, except for reasons involving amusement or historical interest. The more things change, the more they stay the same, which is both a cliche, and also Hardyment’s thesis and in this context, such a revelation.

For example, here is Val Teal on big strollers, which remain, of course, a contentious issue to this day:

“In those days buggies were built. None of your light canvas affairs. They had a solid steel framework and lots of it. They had a big wicker body and hood with a steel bottom with a diaper compartment large enough to hold a dozen or so. The baby-carriage manufacturers expected you to push the baby on really long trips. If you took the notion to walk to Chicago some afternoon to visit your aunt they would not stand in your way. They had prepared a perambulator with ample space for the baby’s and your luggage during your stay. They expected you to have a big baby and push him around until he was three or four years old and they had provided room for this, with enough left over to bring home the groceries, including a watermelon if you were so inclined. The buggy weighed several hundred pounds, several hundred and fifty pounds with the baby and his paraphernalia aboard. We did not have an extra garage to keep it in. It furnished our small dining room very nicely before we could afford a dining room set. While you pushed this young truck around like mad, your tongue hanging out the baby sat like a rosy king, taking in the world with his round eyes, the air with his pink nose.”

It is often said that nobody tells the truth about motherhood, though I think the reality is really that nobody ever listens. Because Val Teal was telling the truth in 1948, Betty Friedan in 1963 Erma Bombeck in the 1970s, Susan Swan in 1992, just to pick a handful of examples. Some early passages from It Was Not What I Expected were so similar to my own experiences, which had come as such a surprise to me when my first baby was born. Like this one, as Teal and her husband arrive at the hospital for their first baby’s arrival:

It is often said that nobody tells the truth about motherhood, though I think the reality is really that nobody ever listens. Because Val Teal was telling the truth in 1948, Betty Friedan in 1963 Erma Bombeck in the 1970s, Susan Swan in 1992, just to pick a handful of examples. Some early passages from It Was Not What I Expected were so similar to my own experiences, which had come as such a surprise to me when my first baby was born. Like this one, as Teal and her husband arrive at the hospital for their first baby’s arrival:

“Across the street a young couple were just getting home. They were laughing and talking softly as he found the key and put it in the door. We could have been just like that as well as not. We could have been just coming home from a party. Why had I been so eager? Maybe I’d die. Maybe we’d never come home from a party like that again together… We had been so happy. We’d had a good life. Why had I had to get ambitious? Darn it all, I didn’t want a baby. I just wanted to go home and go to parties.”

A few pages later, the baby is born, and mother and son are home:

“The Baby cried and cried. I had given up not feeding him at two in the morning long ago. Every time I fed him he went to sleep for half an hour. Then he cried again.

‘I didn’t know it would be like this,’ I wept to Bill. ‘I wish I was back in the hospital.'”

Motherhood was less complicated for previous generations, Teal explains. She describes a trip when her first son was seven months old, the directions they’d had to send ahead, provisions required, their car ridiculously packed. Along they way, they stop for the baby’s sunbath (as dictated by both government pamphlets and the Women’s Home Companion). She writes, “I used to think about [my mother] being cleaned up every afternoon, baking cakes for visitors, sprinting off peppy as a kitten to coffee parties, pushing her baby-sled full of clean babies, and I wished I’d lived then when babies were less complicated…”

Motherhood was less complicated for previous generations, Teal explains. She describes a trip when her first son was seven months old, the directions they’d had to send ahead, provisions required, their car ridiculously packed. Along they way, they stop for the baby’s sunbath (as dictated by both government pamphlets and the Women’s Home Companion). She writes, “I used to think about [my mother] being cleaned up every afternoon, baking cakes for visitors, sprinting off peppy as a kitten to coffee parties, pushing her baby-sled full of clean babies, and I wished I’d lived then when babies were less complicated…”

It Was Not What I Expected takes great joy in dissecting the naiveté of the new mother, insistent upon raising baby according to the book (what book? depends which decade, I suppose). How stupid we all were in those early days, and how determined we were that we would be the masters of motherhood rather than motherhood be the masters of us. Naturally, hilarity ensues.

Memorable scenes include Teal getting locked in the attic while her son sits outside the door eating beads, and the time she hires a simple-minded creature prone to seizures to babysit as she tries to better herself at a meeting of the American Association of University Women and it all goes wrong. (“I began gradually to give up the International Relations section because Hitler seemed to go right ahead doing impolite and smarty things, even though we met every week with luncheons too, instead of teas.)

And like any mother, she frets about play dates:

“I learned at the Child Study Group that children need companionship. If you child did not have others to play with you must do something about it. You must see that other children came to your house. It was a matter of life and death. Or anyway the difference between success and failure. You must drag in companionship. You must inveigle children to come. You must offer them food and toys, anything, to get them there. Companionship was the breath of life to the normal child.”

Teal’s second child just escapes being born in the Piggly Wiggly. “Now I knew all about babies,” she writes. “Peter would be easy to raise. I was experienced. There would be no foolishness about who was boss. I knew who was boss.” Instead of books to raise this baby, she decides, she’ll employ her own instinct. She will let the baby do what he likes.

More adventures in motherhood with boys: the necessary acquisition of a menagerie, dogs, ducks and rabbits. The obligatory paper-route. She helicopter parents, terrified of her boys riding their bicycles and therefore driving along behind them in the car on the way to their music lessons.

More adventures in motherhood with boys: the necessary acquisition of a menagerie, dogs, ducks and rabbits. The obligatory paper-route. She helicopter parents, terrified of her boys riding their bicycles and therefore driving along behind them in the car on the way to their music lessons.

She addresses her determination that her boys shall play with dolls, much to the concern of everyone around her. To which she replies, pre-dating Charlotte Zolotow, “If more boys had been allowed to play with doll there’d be more intelligent fathers. Boys have been taught for too long a time that it is shameful for men to have anything to do with the care and bringing up of children. Men need tenderizing. I’m going to raise them to, first of all, be kind and loving fathers, and considerate husbands.” This chapter is wonderful, and ends with her son packing his doll (Uncle Pat Mulligan), along with a toy revolver on a trip:

“What have you got that for?” I asked. “Leave [the gun] at home. You’ve got enough to carry.”

“No, I gotta have it,” Peter grabbed for the gun.

“What for?” I asked, holding it back.

“If Pat Mulligan turns bad on this trip I’ll have to shoot him in the stomach,” Peter said.

I gave Peter the gun. You never could tell when Pat Mulligan might turn bad.

Teal’s picture book and her memoir are excellent companions. In the former, the little woman cannot rest without noise and goes out of her way to acquire more and more animals to liven up her farm and fill the air with sound. With that same lust for more, Teal writes in her memoir of her own yearning for a large family, a yearning augmented by a miscarriage and a stillbirth. “What no man, no doctor, no woman who has never lost a child can ever know about, is the consuming desire to replace that child that comes to the woman who has lost one.” The losses are not dwelt on here, but neither are they swept under a rug, instead acknowledged in practical terms as part of the vast motherhood experience.

Teal’s picture book and her memoir are excellent companions. In the former, the little woman cannot rest without noise and goes out of her way to acquire more and more animals to liven up her farm and fill the air with sound. With that same lust for more, Teal writes in her memoir of her own yearning for a large family, a yearning augmented by a miscarriage and a stillbirth. “What no man, no doctor, no woman who has never lost a child can ever know about, is the consuming desire to replace that child that comes to the woman who has lost one.” The losses are not dwelt on here, but neither are they swept under a rug, instead acknowledged in practical terms as part of the vast motherhood experience.

Teal’s narrative is remarkable for its blend of wry humour and depth, of exasperation and joy. She so perfectly articulates motherhood as the curious mix that it is of the spiritual and earthly, the perfect and perfectly awful:

“Sometimes I’d look down and see these children around the house and feel very surprised and young and incapable… My goodness, where had they come from?… How in the world had this come about all of a sudden? They weren’t dolls, dream-figures. They were real, alive children, going-to-be men; dear Heaven, what had I done? I had made people! I had made people, Lord help me, people with emotions and plans and wishes and disappointments and longings. People. With souls. And when it would come over me, I’d stand very still and get very scared and helpless feeling. But they always brought me out of it.”

January 22, 2013

The opposite of this scattered post would be an empty space.

1) A friend emailed recently as she was doing a clear-out and wondered if I wanted any of her books on babies and birthing–Jessica Mitford’s The American Way of Birth, Sheila Kitzinger, Alison Gopnik’s The Philosophical Baby. And it was such a pleasure to tell her no. I’d read these books already. I remember poring over Gopnik’s book when Harriet was six weeks old, desperate for some kind of understanding of this creature who’d arrived in my life. I remember the hours spent on internet forums trying to work out a pattern in the pieces of brand new life as a mother. I remember a lot of talking about talking about motherhood, the desperation of these conversations. How important they were for me to have at the time, but how there came a time eventually when I didn’t need them anymore. I have this fantasy that when our new baby arrives in the spring and my life becomes all-baby again that literature might be my one escape from the haze. That I might spend my summer reading about everything except babies, even if it has to be done in the middle of the night while the rest of the world (except the baby) is sleeping. But I’ve never had a second child before. I do not know if my fantasy will come true.

1) A friend emailed recently as she was doing a clear-out and wondered if I wanted any of her books on babies and birthing–Jessica Mitford’s The American Way of Birth, Sheila Kitzinger, Alison Gopnik’s The Philosophical Baby. And it was such a pleasure to tell her no. I’d read these books already. I remember poring over Gopnik’s book when Harriet was six weeks old, desperate for some kind of understanding of this creature who’d arrived in my life. I remember the hours spent on internet forums trying to work out a pattern in the pieces of brand new life as a mother. I remember a lot of talking about talking about motherhood, the desperation of these conversations. How important they were for me to have at the time, but how there came a time eventually when I didn’t need them anymore. I have this fantasy that when our new baby arrives in the spring and my life becomes all-baby again that literature might be my one escape from the haze. That I might spend my summer reading about everything except babies, even if it has to be done in the middle of the night while the rest of the world (except the baby) is sleeping. But I’ve never had a second child before. I do not know if my fantasy will come true.

2) Motherhood still interests me, but on a broader level than the whole strollers on the bus brouhaha and whether breast is really best. The conversations I appreciate most about motherhood are those that don’t usually appear on the pages of glossy magazines, which rise above the Mommy Wars to broaden notions of what motherhood is and can be, and the ways in which different women’s lives are affected by various experience of maternity, and the elusiveness of “choice” (which is so often another fantasy, no?). Anyway, I’ve got more to say on the topic and the most exciting news ever forthcoming in the weeks ahead. Stay tuned.

3) We took a picture of my baby bump! How positively first-pregancy of us! It is not altogether flattering, as I’ve no make-up on, lighting is poor and I’ve had a cold for three days and it shows. But this is me at 22.5 weeks pregnant, which is kind of remarkable. I know many people find pregnancy pictures obnoxious, but as someone who has spent most of my life feeling fat and the last three years in particular trying to hide an unfortunate abdomen post c-section (3 years later, it is no excuse, I know, but still…) it is awfully refreshing to embrace and celebrate the shape I’m in. And it’s a remarkable thing, however ordinary, to have happen to one’s body, to change so much in such a short time, different every day.

4) I keep vague tabs in my mind of how my blog content is divvied up, the grown-up things, the kid things, the women things. I always have this notion that I’m doing terribly well when a string of posts doesn’t reference children or motherhood at all, and yet I don’t fully believe this either. My blog has always been a reflection of life as it is, and small children (and the books they read) have been a huge part of my life for some time now. I could pretend otherwise, but then I’d be left with not much to write about. Anyway, all of which is to say that I’m feeling self-conscious and babyish posting about pregnancy and belly-shots, but then here is where I’m at right now. The opposite of this scattered post would be an empty space.

May 13, 2012

Bad Mommy by Willow Yamauchi

The world already having had its fair share of bad mothers, bad mothers, and bad mothers, I’d wondered if Willow Yamauchi’s new book Bad Mommy was a necessary addition to the canon. But the book turned out to be quite different from what I’d supposed it was, not another tell-too-much so-bad-I’m-awesome mother memoir, but instead a satirical guide to motherhood, the perfect antidote to any baby book I ever read, particularly in the early days.

The world already having had its fair share of bad mothers, bad mothers, and bad mothers, I’d wondered if Willow Yamauchi’s new book Bad Mommy was a necessary addition to the canon. But the book turned out to be quite different from what I’d supposed it was, not another tell-too-much so-bad-I’m-awesome mother memoir, but instead a satirical guide to motherhood, the perfect antidote to any baby book I ever read, particularly in the early days.

And best intentions do start early, don’t they? I spent my pregnancy reading Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth and Pam England’s Birthing From Within, eventually become a compulsive parenting expert, found becoming a mother akin to the universe exploding, and clung to its pieces with my few certainties: cloth diapers, front-facing strollers, not to feed baby to sleep, to breastfeed lying down at night, black and white mobiles, etc. At first there were the things I “knew”, and eventually, with enough confidence and experience, there were actual things that I really learned, though it baffled me how inapplicable my advice seemed to be to other people’s experiences. Why weren’t they taking my certainties on board? And even more baffling– why did I care so much what other people were doing? Why did other people’s (ill-advised, I thought) breastfeeding holds make me crazy? Why did nothing terrify me more than seeing other mothers making different choices from mine, I wondered? And of course, I see now that I was clinging to order in a chaotic world, imagining there was one path to good motherhood and that I was walking on it, because the alternative (which was the reality) was too much consider–that there was no path, and that all of us were all just stumbling blindly, making our own way as best we could.

I’m not sure I could have read Bad Mommy back when I was still clinging, when it was so important to me to be certain. Yamauchi’s irreverence is without restraint, nothing is sacred, and anyone and everyone is a target– she’s fair and balanced in that respect. Let’s face it, she tells us in her introduction, you are a bad mommy. You may be trying to be good, but you’re still bad, or at least somebody is going to tell you so. And in the next 40 chapters, she proceeds to tell us how: you will always be too young or too old to be a good mommy; no matter how you time your pregnancies, you’ll always get it wrong. Even if you remember the folic-acid, there will still be plenty of opportunities to fail your child’s development in utero– sushi, cheese, paint and kitty litter to choose from! You’ll gain too much weight, or not enough. You’ll deliver your baby in an idyllic water birth, and have the baby get stuck in the birth canal, or you will give birth in a hospital with painkillers which will result in an apgar score of less than perfect.

Everything you do as a mother, says Yamauchi, will be wrong, so you might as well have a sense of humour about it. Oh, and the breastfeeding– night nursing leads to tooth decay! Women who pack in breastfeeding are failures! Mommies who breastfeed into toddlerhood are perverts! The chapter on circumcision was my very favourite, the entirety of which I read aloud to my husband whilst laughing hysterically– “A common reason given for circumcision is that men want their little boys to ‘look like them’ down there. This is such a bizarre concept. First of all, what kind of parent and child compare their genitals for familial similarities?…” Though, she writes, don’t circumcise and your son will end up with STDs, Bad Mommy.

And so it goes, through disposable diapers and cloth, how to put your baby down to sleep (and the standards for this, Yamauchi notes, change every ten minutes, along with car seat requirements, and when and how to start solid foods), to vaccinate or not to, to work or stay at home. The point is to go confident in your choices, says Yamauchi, because you’ll only ever be wrong in them.

And there are so many ways to be wrong– I related in particular to the “Crafty Bad Mommy” chapter, as our craft supplies haul is mainly stubby crayons. You can be the Bad Mommy who sends her kid to school sick, or the Bad Mommy with muchhausen by proxy. You’ll have fat kids, or anorexic ones, you’ll look like a frump or a mutton-dressed-as-lamb, and onwards and onwards, so it goes, until you start to see that Yamauchi is joking but she also isn’t.

The book ran a bit too long to my tastes, and I found Yamauchi’s chapters more interesting than the case-studies that followed each of them (though even these had their moments), but in general, Bad Mommy is a great counter to so much of the faux-earnest or overtly polemic conversations about parenting going on all around us these days. Though everything is fair-game in the book, its point is not to abandon your principles as a mother (and for the record, I am still a cloth diaper fanatic. I just shut up more than I used to. Not that anyone actually wears diapers in our house anymore [!!!]), but to embrace them.

To be Willow Yamauchi’s bad mommy is simply to be the mother you are, but with gusto.

April 1, 2012

Sweet Devilry by Yi-Mei Tsaing

Sarah Yi-Mei Tsaing is author of the picture book A Flock of Shoes which we’ve adored for ages, and I’ve wanted to read her book of poetry Sweet Devilry ever since I read her poem “How to dress a two year old” (which begins “Practice by stuffing jello into pants./ Angry jello.) As A Flock of Shoes has autobiographical elements (the story’s main character has the same name as Tsaing’s daughter), there is some delightful overlap between it and Sweet Devilry, though they’re directed at different audiences. I love in particular the reference to Abby’s shoes flying high in the sky in the book’s final poem (though there’s no mention as to whether they sent her postcards).

Sarah Yi-Mei Tsaing is author of the picture book A Flock of Shoes which we’ve adored for ages, and I’ve wanted to read her book of poetry Sweet Devilry ever since I read her poem “How to dress a two year old” (which begins “Practice by stuffing jello into pants./ Angry jello.) As A Flock of Shoes has autobiographical elements (the story’s main character has the same name as Tsaing’s daughter), there is some delightful overlap between it and Sweet Devilry, though they’re directed at different audiences. I love in particular the reference to Abby’s shoes flying high in the sky in the book’s final poem (though there’s no mention as to whether they sent her postcards).

I’ve added Sweet Devilry to my list of essential Motherhood books. The first poem begins, “On the morning of your birth…” and contains the wonderful line, “Learn a good latch, kiddo–/ it pays to hold on/ to someone you love.” And from then on, the book was unputdownable– I read it walking away from the bookstore all the way to the subway, even though my hands were cold. The first section includes poems about ultrasounds, various perspectives of pregnancy tests, poems about two year olds, tantrums and starting daycare.

The next section riffs on other texts, namely government-issued household manuals from the 1920s and well-known fairy tales, to reinvest familiar tropes with narrative. Section 3 is a long poem reworking The Little Mermaid. And finally, Section 4 explores the various corners of contemporary family life, including the joys of home-ownership in a “transitional neighbourhood” (“We find a pair of shat-on men’s underwear/ sitting at the back of our yard,/ casually, as though it’s always been there,/ as if it’s not embarrassed by its own/ telling state”). The rest are poems about loss (in particular of a parent), and how elements of loss and tragedy co-exist with ordinary life, and about the painful fact that love itself is always about letting go.

January 12, 2012

How to Get a Girl Pregnant by Karleen Pendleton Jimenez

Sperm procurement is Karleen Pendleton-Jimenez’ basic challenge as a lesbian who wants to have a baby, a challenge further complicated by fertility struggles. Though the original challenge was pretty complicated from the outset– sperm is hard to come by for these purposes, and if you decide to go through anonymous donors, it’s next to impossible to find matches with your ethnic background, unless that background is white European. With precise, vivid and immediate prose, in her memoir How to Get a Girl Pregnant, Pendleton-Jimenez documents her journey towards pregnancy, which begins very early in her life when she knows she wants to be a mother as strongly as she knows that she’s a lesbian.

Sperm procurement is Karleen Pendleton-Jimenez’ basic challenge as a lesbian who wants to have a baby, a challenge further complicated by fertility struggles. Though the original challenge was pretty complicated from the outset– sperm is hard to come by for these purposes, and if you decide to go through anonymous donors, it’s next to impossible to find matches with your ethnic background, unless that background is white European. With precise, vivid and immediate prose, in her memoir How to Get a Girl Pregnant, Pendleton-Jimenez documents her journey towards pregnancy, which begins very early in her life when she knows she wants to be a mother as strongly as she knows that she’s a lesbian.

As a butch lesbian who wants to be a mother, Pendleton-Jimenez complicates ideas of butchness, and of motherness. But the arrangement has always felt natural to her, and her experiences co-parenting her partner’s children underline this instinct. As she approaches her mid-thirties, she decides to finally take the definitive step towards motherhood–and lesbians don’t do turkey basters anymore, she informs us. Turkey basters are too big, and sperm is far too precious a commodity to unintentionally get stuck up in the bulb at the top. There is also an amusing scene where she poses on her front porch for a photo with the tank the sperm is delivered in: “This may be all the baby gets to see of its biological parents together,” she writes, though upon reflection, she notes that she looks tired and unhappy in the photo. The stress of trying to get pregnant was already taking its toll.

Which would only get worse as she begins to undergo treatments at a fertility clinic, going in for regular visits for monitoring, to check for ovulation, and for fertilization. And in talking about infertility, she breaks a taboo, though this candidness does not come easily. She writes about the pain and isolation of what she’s going through, how women don’t talk about these experiences. She doesn’t want anyone to know, she doesn’t want to be pitied, to be “that woman who’s trying to get pregnant but can’t”, and so she is very much alone in the process. She also addresses the complicated dynamics of being a butch prone on a table being poked on prodded by nurses and technicians, learning to become accustomed to this, and of her strange pleasure in the compliment that her ovaries were “beautiful”. And in the hope each month that this time the pregnancy would take, and the predictable disappointment when it didn’t over and over again.

I know that longing, that desperation to be pregnant. Pregnancy came easily for me, but I remember how badly I wanted it, and identified strongly with Pendleton-Jimenez’ need for a baby. So that when she starts cruising for men at night clubs, I totally get it, and also admire the openness with which she writes, how she makes herself as vulnerable in her narrative as she did in the experiences she writes of. The openness works, because the writing is so good, beautifully unadorned and to the point. Pendleton-Jimenez also manages to write with both poignance and humour, and indeed, I laughed and I cried as I read this book. Like all great memoirs, this is an intimate story that manages to connect with the universal, and the narratives of pregnancy and motherhood are so much richer for it.

March 24, 2011

The original chronicler of motherhood

Lately I’ve been turning to Shirley Hughes’ Alfie books whenever I’m in need of parenting guidance. (I am also reading another book called Toddler Taming that recommends spanking and tying up children with rope, quite unabashedly, but then it was written in 1984 when that sort of thing was de rigueur. But actually, casual cruelty aside(!), it’s a great book. Just let me explain… Review to come.) I love Shirley Hughes, and I really love Alfie, and Harriet loves him too, so we’ve read his stories an awful lot.

Lately I’ve been turning to Shirley Hughes’ Alfie books whenever I’m in need of parenting guidance. (I am also reading another book called Toddler Taming that recommends spanking and tying up children with rope, quite unabashedly, but then it was written in 1984 when that sort of thing was de rigueur. But actually, casual cruelty aside(!), it’s a great book. Just let me explain… Review to come.) I love Shirley Hughes, and I really love Alfie, and Harriet loves him too, so we’ve read his stories an awful lot.

And I don’t think the experience of parenthood has ever been better articulated in literature than with this one paragraph from Alfie Gets in First: “Mum put the brake on the push-chair and left Annie Rose at the bottom of the steps while she lifted the basket of shopping up to the top. Then she found the key and opened the front door. Alfie dashed in ahead of her. “I’ve won, I’ve won!” he shouted. Mum put the shopping down in the hall and went back down the steps to lift Annie Rose out of her push chair. But what do you think Alfie did then?”

This kind of tedious maneuvering is the story of my life, and if you’ve ever lived such a life, you understand that Mum has spent ages strategizing the perfect order in which to perform the tasks that will deliver her children and groceries into her house with maximum efficiency. I absolutely adore that recognition. Never mind Rachel Cusk as chronicler of motherhood, no, Shirley Hughes absolutely did it first.

I love her illustrations, and am fascinated by the interior of Alfie’s house. Harriet likes to comb the pictures for teapots, and I love to spot what else is cluttering the corners: discarded shoes, soccer balls, old ties, umbrellas, toy teacups, tennis rackets, folded strollers, and acorns.

Though Alfie’s mum, however rumpled, is a far better mum/mom than I am. Which I’m absolutely fine with, having chosen to take Alfie and Annie Rose’s dad as the parent upon which I model myself. He’s not around as much as Mum (and there I fall short. I never seem to go away), but when he is around, he’s usually behind a newspaper. I love that when in Alfie’s Feet, he takes Alfie to the park, he takes care to bring his book and his newspaper. A parent after my own heart, I think, and Alfie doesn’t seem any less content as he splashes through the puddles, his dad reading the paper on a park bench behind him.

More: