August 1, 2017

Camping With Louise Penny

I have developed a hammock habit over the last few years, and most lazy summer afternoons you’ll find me in my urban backyard enjoying a warm breeze and basking in the shade of our enormous silver maple. Reading, obviously. And the best thing about a hammock habit is that it can be altogether portable if you’ve got the right hammock, which I do, complete with a foldable frame and a carrying bag. It is the heaviest most awkward portable object imaginable, but it’s mine, and it’s the most essential item in our mountain of equipment when we’re packing the car to go camping.

We’re not natural campers, my family. I’m a bad Canadian and my husband is an immigrant, and so camping (along with ice skating) is an activity we’ve had to work hard to fall in love with—mostly for the sake of the children. But because camping doesn’t involve falling all over perilous slippery surfaces while wearing blades on our shoes, we’ve actually had some luck with this. This summer will be our fourth year pitching a tent out in the wilderness—or rather, more realistically, while my husband is busy pitching the tent, I’ll be setting up my hammock.

The hammock itself is not the only ingredient necessary for a successful camping weekend, however. We need bug spray, and sleeping pads, fire-starters and marshmallows, and we need books. And not just any books. For me, I’ve learned that a weekend camping in the woods is not completely unless I’ve got a big fat Louise Penny novel to be absorbed in. The hammock would be wasted without it.

Miles from the cozy civilization invoked by the fictional Three Pines, with its bistro, B&B, boulangerie and bookshop, I spend our camping afternoons in my hammock wholly wrapt by Penny’s novels, compelled by her character, Chief Inspector Armand Gamache and his call to duty. There will be some sort of crime, either immediately or eventually a murder, and any gruesomeness related to this matter will be abated by the scenes Penny sets in Three Pines, a place as familiar to me as my own neighbourhood is. I pick up these books in anticipation of returning to Three Pines, and to its people, who are complicated, irreverent, brilliant, warm and funny. And there, in the middle of the woods in Ontario, insects buzzing about and sunshine peeking in through the canopy of tall skinny pine trees, there I’ll be.

You can almost smell the croissants warm from the oven, which is saying something, when a fictional redolence can overpower the actual smell of outhouse.

(We had an amazing, albeit bug-infested, camping trip this weekend. Lucky me, I had an ARC of Louise Penny’s new novel Glass Houses in hand. You can see more photos on my Instagram.)

January 17, 2017

Reconciling

The first definition of “reconcile” in the Merriam Webster is ” to restore to friendship or harmony <reconciled the factions>” but it’s the second definition that is more meaningful to me: “to make consistent or congruous <reconcile an ideal with reality>.” This definition certainly resonating in general, because in the past two months my ideals and reality have certainly been at odds, and reconciling that has been a process. The world is more complicated than I ever knew, which makes “restoring to friendship and harmony” seem like a pipe-dream, except: restoring, how? Because when was there ever friendship and harmony? It all sounds a bit like the notion of making America great again—elusive and facile. The first definition is a misnomer. Reconciliation is a process, and in order to be properly it is a process that will never end.

I’ve been thinking a lot about reconciliation lately, as I’ve been reading I’m Right and You’re an Idiot: The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean It Up. A friend of mine has also recommended Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair. I’m interested in and troubled by the way that people seem unable to constructively disagree with each other. (Another book along these lines that I’ve appreciated is Creative Condition: Replacing Critical Thinking With Creativity, by Patrick Finn.) I take some solace in the fact that people in disagreement, while inconvenient, is actually much healthier than the alternative, and that the potential for learning is infinite. A community in which everybody though the very same thing, and nobody challenged anyone or asked any questions, would be the very worst thing I could imagine. Worse even than the state we’re in now.

Remember my mantra for 2017, “Listen. Be Better.” I’m trying. It’s a challenge, and such an opportunity. Once upon a time, when I was young and things were simpler, I fervently underlined the following bit from Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, a play I loved: “This is the best time possible to be alive. When everything you know is wrong.” Such a prospect is more terrifying than I ever thought it would be, now that we’re kind of here and, you know, with the collapse of the world order, but still, there is something extraordinary about it too. I’m thinking about reconciliations big and small, in terms of domestic politics and literary criticism, even. Literary criticism, especially, because I wonder if this is a constructive metaphor with which to understand the process that has to happen in order for anything to happen.

Literary criticism, the best kind, is a conversation. A back-and-forth, a broadening, the prying of a text wide open. The best kind of literary criticism isn’t just about the text itself, but it’s about everything, and it invites big questions and many different answers. It provokes debate and causes the reader to change her mind—about the text, about the world. It’s not about whether a text is necessarily good or bad, but about the things it makes us think about, the places it takes its readers beyond itself. Literary criticism is a process, a collaborative ongoing pursuit which requires generosity, openness, consideration and respect on the part of the players involved. If no one’s listening, nothing happens, but if everyone is willing, anything can.

I was thinking about all this as I read Debbie Reese’s review of the award-winning picture book, Missing Nimama, which I reviewed in 2015—and you can read my review here. I am a huge admirer of Debbie Reese’s scholarship and advocacy about representations of Indigenous people in children’s books—she’s taught me a lot and she challenges my understanding in uncomfortable and constructive ways. She’s not afraid to go up against really popular authors—see her review of Raina Telgemeier’s Ghosts. I don’t always agree with her assessments of certain books, mostly because there are so many lenses through which readers approach a book, and hers is one, but I’ve never found her to be wrong.

While I still appreciate Missing Nimama and celebrate its success, Reese’s review shows me my own weaknesses in approaching it as a writer and a critic. Reese writes: “To me, however, Missing Nimama …. strike[s] me as something Canadians can wrap their arms around, to feel like they’re facing and acknowledging history, to feel like they’re reconciling with that history.” She continues, ” To many, this review…will feel harsh. Most people are likely to disagree with me. That’s par for the course, but I hope that other writers and editors and reviewers and readers and sponsors of writing contests will pause as they think about projects that involve ongoing violence upon Native women.”

And this is just the point. The pause, the reflection. Disagreeing is even okay, but it’s failing to consider that is inexcusable. The point is the conversation, the questions that are asked, which are far more important than the answers. And how we take these questions with us, this broadened perspective, with the books we read and the books we write. The point is to listen, and then be better.

UPDATE From Carleigh Baker’s review of Katherena Vermette’s The Break:“A generous storyteller, Vermette does not take it for granted that all readers will inherently understand how damaged the relationship between indigenous people and Canadian society has become. As readers, we can honour this generosity by not allowing ourselves to be lulled into a satisfying sense of camaraderie, having suffered alongside fictional characters. We can honour it by not repeating over and over how strong the women in this book are. It is true, they are strong. But let us not nod our heads in grim recognition of this strength, as if acknowledgement equals solidarity [emphasis mine]. Let us not pull our lips into thin lines and furrow our brows and express amazement at their resilience, as if its origin is a mystery. This makes it too easy to dismiss.”

November 10, 2016

How Women’s Fiction Can Save Us All

On Tuesday night I started reading The Little Virtues, by Natalia Ginzburg (which came to my attention in Belle Boggs’ essay in The New Yorker, “The Book That Taught Me What I Want to Teach My Daughter”). Not a comfort read, exactly, although there is some of that, but then the first essay is about her years in exile from the Fascists in Italy before her husband died in prison: “Faced with the horror of his solitary death, and faced with the anguish of what preceded his death, I ask myself if this happened to us—to us, who bought oranges at Giro’s and went for walks in the snow.”

On Tuesday night I started reading The Little Virtues, by Natalia Ginzburg (which came to my attention in Belle Boggs’ essay in The New Yorker, “The Book That Taught Me What I Want to Teach My Daughter”). Not a comfort read, exactly, although there is some of that, but then the first essay is about her years in exile from the Fascists in Italy before her husband died in prison: “Faced with the horror of his solitary death, and faced with the anguish of what preceded his death, I ask myself if this happened to us—to us, who bought oranges at Giro’s and went for walks in the snow.”

There are some moments when it’s important to face things head on, and to learn from someone who has gathered wisdom from decades of experience.

Women’s fiction doesn’t usually get that much credit for helping its readers face things head-on: these books are escapes, they’re beach reads. Fluffy rather than edgy, entertainment instead of education. Women’s fiction that takes on “issues” is its own sub-genre, and there tends to be a formula as to how these stories are executed, with tidy resolutions. Faced with a tyrant being elected American President, we’re supposed to be turning to weighty French philosophers, right? Or Natalia Ginzburg (which I really do recommend). Certainly not Jodi Picoult.

What is political? I’ve been thinking about this in terms of the novel I’m writing at the moment, about two women’s friendship over decades. About my forthcoming book too, Mitzi Bytes, which is about a woman who dares to have a voice and what the consequences are—but it’s also more complicated than that, because she’s not entirely innocent in her own downfall. My character is flawed, scared, arrogant and insensitive. A lot of the book is about her relationship with other women—her friends, her sister-in-law, her mother, the other other mothers at her children’s school. And what’s the point of a story like this, I wonder, at the moment of onset of a world like that?

What is political? I’ve been thinking about this in terms of the novel I’m writing at the moment, about two women’s friendship over decades. About my forthcoming book too, Mitzi Bytes, which is about a woman who dares to have a voice and what the consequences are—but it’s also more complicated than that, because she’s not entirely innocent in her own downfall. My character is flawed, scared, arrogant and insensitive. A lot of the book is about her relationship with other women—her friends, her sister-in-law, her mother, the other other mothers at her children’s school. And what’s the point of a story like this, I wonder, at the moment of onset of a world like that?

The question of how women get along and the ways in which they don’t is fascinating to me. I suspect that every story I ever write will be about this. And I am also fascinated by how 53% of white American women voted against a strong, experienced feminist and instead for a noted misogynist. I am fascinated by the women who cheer for him exuberantly and claim that he could grope their pussies anytime. Who are these people? What planet do they live on? Could it possibly be the same one as me?

Women’s fiction tells women’s stories. Women’s fiction also sells. And it occurs to me that this genre has the best capacity of any to help us better understand each other. The authors who are writing nuanced stories about the dynamics of sisterhood are laying out a path of relations. Why are women’s friendships so intense? How come when we don’t like a woman we don’t like her so much. Why is it so challenging to see a woman making choices that are different from yours? Why is it all so personal? Why can mother/daughter relationships be so fraught?How come when we have so much in common (and when so much is at stake) we can be so vehemently opposed?

Women’s fiction tells women’s stories. Women’s fiction also sells. And it occurs to me that this genre has the best capacity of any to help us better understand each other. The authors who are writing nuanced stories about the dynamics of sisterhood are laying out a path of relations. Why are women’s friendships so intense? How come when we don’t like a woman we don’t like her so much. Why is it so challenging to see a woman making choices that are different from yours? Why is it all so personal? Why can mother/daughter relationships be so fraught?How come when we have so much in common (and when so much is at stake) we can be so vehemently opposed?

Part of it is because we’re human, of course. Human beings are complicated. This is awkward, but is in fact one of the best things about humans. While these differences are difficult to navigate, it would be terrifying if we were all the same. Who would push us to be better? How would we know what to rise above? Part of it too comes down to something I’m working out about gender and specificity—a guy in a suit is a guy in a suit, and any guy is going to see that and identify, but women have different hair colours, and different hair styles, and maybe she’s wearing a pantsuit and maybe she’s wearing a dress, and does she stay home and bake cookies or is she Diane Keaton in Baby Boom, and all these differences make it easier to find something to dislike about somebody. Unless, of course, you just happen to dislike guys in suits as a blanket rule (and lately I am thinking there is something to that).

In women’s fiction, I think, we can get to the point of figuring it out. We need authors to consider these questions and write thoughtful and nuanced stories about them (and this is happening now). We need readers too to pick up these books and reading with questions in mind, to allow themselves to be challenged by some of the ideas contained therein. I need to get a better sense of that 53% of white women and what they were voting for or against. The women who supported Clinton but did not dare to admit it beyond the confines of a secret Facebook group need to grapple with these questions too, because they bear some responsibility as well for what happened—women who won’t dare to make Thanksgiving dinner uncomfortable. White liberal women who need to (for the sake of their children, their country) rise up and flip that fucking table, and let their fathers and brothers (and sisters and mothers) know just what has been stolen from them with this election.

In women’s fiction, I think, we can get to the point of figuring it out. We need authors to consider these questions and write thoughtful and nuanced stories about them (and this is happening now). We need readers too to pick up these books and reading with questions in mind, to allow themselves to be challenged by some of the ideas contained therein. I need to get a better sense of that 53% of white women and what they were voting for or against. The women who supported Clinton but did not dare to admit it beyond the confines of a secret Facebook group need to grapple with these questions too, because they bear some responsibility as well for what happened—women who won’t dare to make Thanksgiving dinner uncomfortable. White liberal women who need to (for the sake of their children, their country) rise up and flip that fucking table, and let their fathers and brothers (and sisters and mothers) know just what has been stolen from them with this election.

And what better place to find stories of uncomfortable dinners and torrid family dynamics? Why, women’s fiction, of course. (And Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections too, which totally falls into the category.)

We need to be reading more authors of colour too to find out what’s happening at the dinner tables of families who might not necessarily look like yours. I’ve been so grateful to those who chose to market books by Brit Bennett and Angela Flournoy as mainstream fiction this past while so that their books came onto my radar. I am going to continue to actively seek out diverse voices in commercial fiction and use whatever platform I have to amplify them, and hope that other white commercial writers will do the same, for its a genre that’s as disturbingly white as any other.

We need to be reading more authors of colour too to find out what’s happening at the dinner tables of families who might not necessarily look like yours. I’ve been so grateful to those who chose to market books by Brit Bennett and Angela Flournoy as mainstream fiction this past while so that their books came onto my radar. I am going to continue to actively seek out diverse voices in commercial fiction and use whatever platform I have to amplify them, and hope that other white commercial writers will do the same, for its a genre that’s as disturbingly white as any other.

We need to support, and promote too, commercial writers who dare to be overtly political in their work, to read them as thoughtfully and generously as Roxane Gay reviewed Jodi Picoult in The New York Times. Let’s celebrate the commercial writers who are daring to take risks, as Marissa Stapley suggests in our conversation on commercial fiction. Writers need to keep striking that perfect balance between books that people are actually going to want to read, and books that give us something to think about. Books that build bridges, or at least look-out points.

The work commercial women writers are doing has always been important, but perhaps it’s never been more important than right now.

June 28, 2016

Book Publishing: The Long View

Yesterday I responded to a tweet by Joni Murphy (remember Joni Murphy? She wrote the wonderful novel Double Teenage that I devoured last month) about the ridiculously small window of books coverage in the mainstream media. She’s absolutely right—once the “new release” glow fades, so does a lot of interest…but I suggested that this doesn’t matter. I mean, yes, it would be altogether excellent to find oneself on a bestseller list the week one’s book was published, and for the momentum to be undeniable and inexhaustible, and to have your book be everywhere. Yes, authors do need to work and hustle to get the word out for sure. But here it is: you can only do the best that you can do. And even that is not really guaranteed to get results. And so what an author really needs to do is be satisfied with immediate coverage, but also keep the long view, and have faith in the book and its readers.

For sure, this kind of faith is not the stuff of bestsellerdom, but ultimately it is what really matters. It’s the difference between your book living on someone’s bookshelf for years and years, and being put out on the curb. It means your book not being available en-masse at secondhand bookstores six weeks after the pub date (and hello copies of The Nest and The Girl on the Train. I see you!) It means real people connecting with your work rather than just hearing about it, knowing the cover. The thing about books, good books, see, is that they have long lives, even if it’s hard to measure just how. Although the most excellent thing about the internet is that we do have some kind of a record now, a way of registering reader responses long past the on-sale date. (“The standards we raise and the judgements we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work,” writes Virginia Woolf in her 1925 essay “How Should One Read a Book,” anticipating the literary blogosphere[s]). It would be really wonderful to write a book that set the world on fire, but it’s just as stunning for me as a writer to discover, say, that my book is still being picked up and appreciated over two years after it first was published.

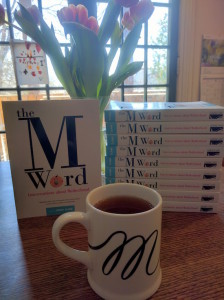

My point proven by two things that happened after my exchange with Murphy: last night I discovered a blog post from last month by the fantastic Red Tent Sisters (who I met when they were at our book launch way back when…) called “Why Is Mothering so Difficult?” It’s a terrific post, but I was even more thrilled by their suggestion that reading a book like The M Word might make mothering a little bit less difficult. They’ve also included The M Word on their Top Fifty Beautiful Books for Soul Sisters, which you can receive if you sign up for their newsletter (and here’s a tip—if you put somebody’s book on a list they receive if they sign up for your newsletter, that somebody will ALWAYS sign up for your newsletter). So I was feeling pretty good about that, and then this morning I was tagged on Instagram by a woman called Leah Noble with a gorgeous photo of The M Word alongside a just-as-delicious-seeming breakfast. Two signs from the universe that the book goes on, after a while of radio silence. Yes, both readers are connected with writers in the book, so I’m not suggesting that the whole thing is made from fairy dust, but there is an element of serendipity about it. You really do have to trust that the book will find its way—and the good books really will. Even if sometimes the ways are small and quiet.

My point proven by two things that happened after my exchange with Murphy: last night I discovered a blog post from last month by the fantastic Red Tent Sisters (who I met when they were at our book launch way back when…) called “Why Is Mothering so Difficult?” It’s a terrific post, but I was even more thrilled by their suggestion that reading a book like The M Word might make mothering a little bit less difficult. They’ve also included The M Word on their Top Fifty Beautiful Books for Soul Sisters, which you can receive if you sign up for their newsletter (and here’s a tip—if you put somebody’s book on a list they receive if they sign up for your newsletter, that somebody will ALWAYS sign up for your newsletter). So I was feeling pretty good about that, and then this morning I was tagged on Instagram by a woman called Leah Noble with a gorgeous photo of The M Word alongside a just-as-delicious-seeming breakfast. Two signs from the universe that the book goes on, after a while of radio silence. Yes, both readers are connected with writers in the book, so I’m not suggesting that the whole thing is made from fairy dust, but there is an element of serendipity about it. You really do have to trust that the book will find its way—and the good books really will. Even if sometimes the ways are small and quiet.

And here’s another thing that I discovered last night, the other side of the publishing coin, eight months before the release date. My novel Mitzi Bytes is now available for pre-order, and unless I have a rabid superfan I am unaware of, my sister purchased the very first copy last night. But this doesn’t mean that it’s too late for you: you can pre-order the book at Chapters Indigo, or from Amazon, or head over to your local proper bookshop to do so.

(But my point is that even if you don’t, it doesn’t fundamentally matter. Life is long and good books are even longer.)

May 17, 2016

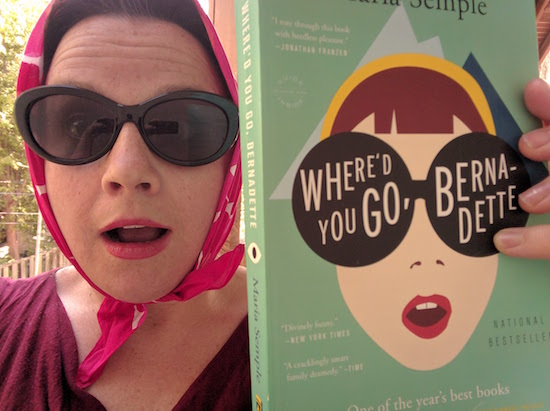

New Maria Semple!!!

I really am this excited about the news of a new book by Maria Semple coming this fall. You can learn more about it and also read an excerpt here. (Yay!!!) Today Will Be Different is out in October.

May 9, 2016

Books are not going away

“Books are not going away any more than family is going away, any more than community is going away, anymore than love and intellectual inquiry are ever going away. Poetry is never going away—and yes, it’s important to keep these two ideas in your head at the same time: 1) hardly anyone reads poetry and 2) poetry has always existed.”

“Books are not going away any more than family is going away, any more than community is going away, anymore than love and intellectual inquiry are ever going away. Poetry is never going away—and yes, it’s important to keep these two ideas in your head at the same time: 1) hardly anyone reads poetry and 2) poetry has always existed.”

—Lynn Coady, Who Needs Books?

April 21, 2016

Light and darkness, dancing together

This morning I dropped Iris off at playschool, and noticed pussy willows in a jar on the counter, which took me back to a scary time we went through through just over three years ago now. It was a time in which I learned that it was possible to navigate life even in the presence of one’s deepest fears, and also that doing so sometimes required errands such as an excursion with shopping list consisting only of a bouquet of pussy willows and a tub of chocolate ice cream. I remember that with the pussy willows, I finally began to feel better, and I think I was thinking of A Swiftly Tilting Planet at the time, but I didn’t pick it off the shelf to get the reference.

This morning I dropped Iris off at playschool, and noticed pussy willows in a jar on the counter, which took me back to a scary time we went through through just over three years ago now. It was a time in which I learned that it was possible to navigate life even in the presence of one’s deepest fears, and also that doing so sometimes required errands such as an excursion with shopping list consisting only of a bouquet of pussy willows and a tub of chocolate ice cream. I remember that with the pussy willows, I finally began to feel better, and I think I was thinking of A Swiftly Tilting Planet at the time, but I didn’t pick it off the shelf to get the reference.

But yesterday morning I was walking to school with my seven-year-old neighbour who’s currently in the middle of A Wrinkle in Time and has the other books in the series before her, and I told her how much A Swiftly Tilting Planet still means to me as an adult. It was the book I picked up in September 2001, after two planes flew into buildings and we wondered if the world as we knew it was entirely gone. I remember the comfort it brought me, the comfort it always has.

But yesterday morning I was walking to school with my seven-year-old neighbour who’s currently in the middle of A Wrinkle in Time and has the other books in the series before her, and I told her how much A Swiftly Tilting Planet still means to me as an adult. It was the book I picked up in September 2001, after two planes flew into buildings and we wondered if the world as we knew it was entirely gone. I remember the comfort it brought me, the comfort it always has.

Mrs. Murry said, “I remember my mother telling me about one spring, many years ago now, when relations between the United States and the Soviet Union were so tense that all the experts predicted nuclear war before the summer was over. They weren’t alarmists or pessimists it was a considered, sober judgement. And Mother said that she walked along the lane wondering if the pussy willows would ever bud again. After that, she waited each spring for the pussy willows, remembering and never took their budding for granted again.

I took it down off the shelf this morning to find the pussy willows paragraph, and realize that I absolutely have to reread this book again. And I considered how fundamental it might have been in cementing my understanding of the cosmos, the world.

Darkness was, and darkness was good. As was light. Light and darkness dancing together, born together, born of each other, neither preceding, neither following, both fully being in joyful rhythm.

October 26, 2015

Good things to know

Okay, I know it’s not even Halloween, but have you heard about the 2015 Short Story Advent Calendar? It’s better then chocolate (apparently?), 24 stories for readers to open every day leading up until Christmas. Contributors include Pasha Malla, Jess Walter, Heather O’Neill, Richard Van Camp, and Zsuzsi Gartner, and bunch of others whose identities are staying secret (but a few of whom emailed me on the down-low to let know they were involved, leading me to order my calendar. Trust me: you’re going to want to get in on this). Kudos to Michael Hingston and Natalie Olsen for taking the initiative and making it happen.

Okay, I know it’s not even Halloween, but have you heard about the 2015 Short Story Advent Calendar? It’s better then chocolate (apparently?), 24 stories for readers to open every day leading up until Christmas. Contributors include Pasha Malla, Jess Walter, Heather O’Neill, Richard Van Camp, and Zsuzsi Gartner, and bunch of others whose identities are staying secret (but a few of whom emailed me on the down-low to let know they were involved, leading me to order my calendar. Trust me: you’re going to want to get in on this). Kudos to Michael Hingston and Natalie Olsen for taking the initiative and making it happen.

And the reason we’re talking about it now is that the calendar is available as a one-time, limited edition print run. By which I mean: Get it while you can.

Oh, and another thing? Remember the panel I took part in at Quill & Quire about whether we’re living in a golden age of Canadian picture books? It’s now online and you can read our discussion here.

June 21, 2015

Where books go to die

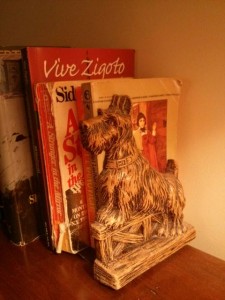

In monumental news, we spent a night away from our children this weekend for the first time in three years on the occasion of our 10th anniversary. They stayed with my mom while we embarked upon a getaway to a nearby resort with an unpretentious rustic feel. We had a wonderful time and it was not so rustic and unpretentious that I didn’t get to drink wine a jacuzzi tub, but the bookishness was extraordinary in its awfulness. There were books everywhere, and it was like they’d cleared out the dregs of every church basement book sale ever. There was a book called How to Get Things Cheap in Toronto that was published in 1977. I was pleased to find a Sidney Sheldon paperback in our room, because he was one of my formative novelists. So many hideous hardbacks. We also had two books by a novelist called Susan Howatch whose garish dust-jackets intrigued me, and I might have read them if not for the must and that I was happily away with The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson and How You Were Born by Kate Cayley (which is so very good). I was also impressed by the Scottish Terrier bookends. And I’m not even kidding.

In monumental news, we spent a night away from our children this weekend for the first time in three years on the occasion of our 10th anniversary. They stayed with my mom while we embarked upon a getaway to a nearby resort with an unpretentious rustic feel. We had a wonderful time and it was not so rustic and unpretentious that I didn’t get to drink wine a jacuzzi tub, but the bookishness was extraordinary in its awfulness. There were books everywhere, and it was like they’d cleared out the dregs of every church basement book sale ever. There was a book called How to Get Things Cheap in Toronto that was published in 1977. I was pleased to find a Sidney Sheldon paperback in our room, because he was one of my formative novelists. So many hideous hardbacks. We also had two books by a novelist called Susan Howatch whose garish dust-jackets intrigued me, and I might have read them if not for the must and that I was happily away with The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson and How You Were Born by Kate Cayley (which is so very good). I was also impressed by the Scottish Terrier bookends. And I’m not even kidding.

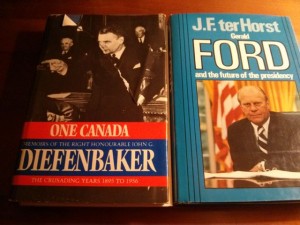

I’m really not. Not being snarky either. I love book collections like this, shelves packed with books that almost nobody wants to read. Where else in the world are you going to find a John Diefenbaker memoir beside a book called Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency? There’s nowhere else in the world anymore where such books belong. They’re kind of there for the decor really, but so unpretentiously, attractively faded like the armchairs. Somebody’s fancy, perhaps, but probably not. And I love that nobody even cares about that. I love how far such a collection would force you to read outside the lines, were you to arrive there otherwise bookless. And I think we’ve completely found the place where old books go to die, but it’s such a nice place. What an afterlife. Today’s literary wunderkinds could only hope for such a fate.

I’m really not. Not being snarky either. I love book collections like this, shelves packed with books that almost nobody wants to read. Where else in the world are you going to find a John Diefenbaker memoir beside a book called Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency? There’s nowhere else in the world anymore where such books belong. They’re kind of there for the decor really, but so unpretentiously, attractively faded like the armchairs. Somebody’s fancy, perhaps, but probably not. And I love that nobody even cares about that. I love how far such a collection would force you to read outside the lines, were you to arrive there otherwise bookless. And I think we’ve completely found the place where old books go to die, but it’s such a nice place. What an afterlife. Today’s literary wunderkinds could only hope for such a fate.

June 10, 2015

My Best Books of the Year (so far!)

Nearly midway through the year, I can say that 2015 has yielded some wonderful books. And while the difficult thing about having a mind is that details fall out of it as time passes, a blog can counter that. So let’s remind us both of the best things I’ve read this year (so far!) and perhaps some of the titles can spur on your own summer reading list.

The Devil You Know, by Elisabeth de Mariaffi

The Big Swim, by Carrie Saxifrage

Born to Walk, by Dan Rubinstein

Welcome to the Circus, by Rhonda Douglas