November 24, 2025

My Reading Year Reflections

With weeks of 2025 still to go, I’ve already hit my goal of reading 200 books, a goal that is somewhat arbitrary, meaningless, and paltry when you actually think about all the books in the world that I’ll never get to read, but still is pretty substantial in the face of all that, although it only means anything because of how much I’ve loved reading these books, how many of these books I truly loved. Books loved are what I measure out my life in, never mind coffee spoons, and while I know focusing on numbers is kind of irritating (“It’s about quality, not quantity,” so spoke that rare school librarian from my past who did not like me, and that criticism lives rent-free in my head, don’t worry!), but being a fast reader is pretty much my only remarkable skill, so can we let me just have that? Do people go around telling Andre De Grasse not to focus on his speed because it’s making all us slow-walkers feel bad? No, they do not.

If you’re curious about how I find the time to read, I shared some of my top tips here! (#1 is “Get Your Blood Checked,” which really did lead to an entire extra hour of reading every day after I learned that my iron count was low and started taking supplements, and was thereafter able to get up in the morning.)

And in addition to the books themselves, here are some things that helped make my reading year remarkable.

- So much nonfiction. Fiction is my usual lane, but with the world being extra weird and hard to understand in 2025, having nonfiction to help me puzzle it all out has been so helpful and even sometimes reassuring. Diving deep into a subject instead of merely scrolling has also been a nice counter to anxiety. Standout titles that have helped me make sense of the world this year include At a Loss for Words, by Carol Off (which just came out in paperback); When the Clock Broke, by John Ganz; In Crisis, On Crisis: Essays in Troubled Times, by James Cairns; How to Survive a Bear Attack, by Claire Cameron; Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything, by Colette Shade; The Snag, by Tessa McWatt; Encampment, by Maggie Helwig; Storm the Ballot Box: An Inside’s Guide to a Voting Revolution, by Jo-Ann Roberts; Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, by Mark Bourrie; and Water Borne, by Dan Rubinstein.

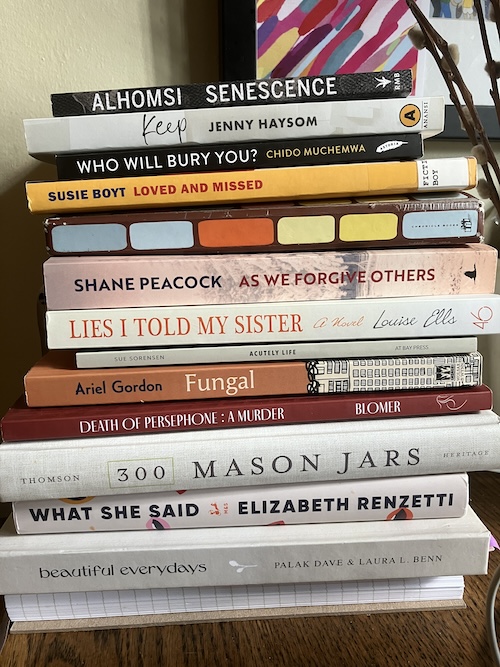

- A focus on Canadian small press books. While I’ve always been a fan of Canadian small press books (which is to say books that are published by presses that aren’t Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, or Harpercollins), I’ve never made them my religion. Especially since market forces mean that the big presses are always going to be able to attract the big deal books that everybody is most excited about (whether that attention is warranted or not) and—this is a controversial statement, I realize—not all small press books are necessarily great and/or to my taste. Sometimes the former is because they lack the resources to fully invest in the production process, which undermines the reader experience. Sometimes the latter is because the very job of a small press is to publish the odd and underrated and not to cater to the widest commercial appeal. Sometimes both factors have meant that small press books have not been as much of my reading focus as they should be. But this year, I decided to make my “On Our Radar” column at 49thShelf a round-up of my own reviews of Canadian small press books, and has that ever been rewarding, pushing me to make small press titles a bigger part of my reading life, resulting in an expansive, transporting, and so much more interesting experience.

- The library. I’ve borrowed books from the library this year more than ever. This is especially convenient since I live in a city with one of the largest library systems in the world, putting so many great books at my fingertips. It’s meant I’ve been able to read a lot of hyped books I wasn’t sure about without getting invested—like, say, The Plot and The Sequel, by Jean Hanff Korelitz. Putting books on hold at the library before they’re released means that I’ve ended up getting to read brand new books before anybody else in the library system OR that I’ve had to wait months and months for my hold to finally arrive, and there are advantages to both of these. The library has allowed me read widely and keep things interesting. (Having just three weeks in which to read a high demand book that can’t be renewed also helps me focus and get the book read, whereas it otherwise might linger on my shelf forever…)

- Bookseller recommendations. It might be hard to tell because I’m still in Instagram a lot, but Bookstagram has factored a lot less into my reading experience this year, which has made my reading more diverse and interesting. And a highlight of this has been heading into bookshops and letting bookseller recommendations decide my purchases—and it’s had me ending up with books like The Road to Tender Hearts, So Far Gone, The Correspondent, and more. (See also “The Booksellers’ List,” new from the Canadian Booksellers Association, which is just definitively excellent. These booksellers have got taste!)

- Weird avenues. My reading regrets most years involve not having pursued enough of these. Not this year though, which makes me very happy. This is partly because I dove into this year with a number of reading projects on the goal, including reading everything by Elizabeth Strout in order of publication (DONE! It was THE BEST!), rereading Carol Shields (I’m slowly going about it, have read up to Swann), and reading Margaret Laurence’s Manawaka books (need to reread The Fire Dwellers and I’m DONE!). None of these authors are that weird, I realize, but anything that isn’t the New York Times bestseller list is a little bit weird these days. I’ve also read a few books in translation, have done plenty of rereading, and feel like I’ve been free to take the wheel in terms of reading what I want to read (which is the nicest freedom I know).

- Reading on my own. A big part of my year even beyond reading has been relearning that not everything I do has be recorded online, and book reviews are included. I was feeling a lot of pressure to write something about every book that came across my path, as though it didn’t exist unless everybody knew that I’d read it, and letting that go has been really freeing and has brought real ease into my reading life.

October 10, 2025

Sometimes Magic

A year ago today was a great day, because it was the day I met Suzy Krause when she came to town to do an event with Marissa Stapley at Type Books in the Junction. Suzy is a ridiculously talented author and downright radiant human who came all the way from Saskatchewan to promote her novel I Think We’ve Been Here Before, and I loved her immediately, and not JUST because she’s a blogger-turned-novelist just like I am and had had a copy of my debut novel on her shelf for years before we finally connected. And before the event, we all went out for dinner, along with the writer Sherri Vanderveen, and we talked about everything, including where I was at in my own career, with a novel on submission, no clue as to what was coming next, and I was trying to be more comfortable with having no expectations, with just living in the moment I was in.

That night after the event, as Suzy and I caught the subway east on the Bloor Danforth line, I FINALLY managed to catch the transit poster for Marissa’s then-new release, The Lightning Bottles, a book I love so much and which was kind of the novel Marissa has been working towards her whole career in terms of literary achievement. It was also exciting because I’ve dreamed of having a book on a transit ad, and having my friend’s book on a transit ad is the closest I’ve come. Because it never rains but it pours, we encountered the poster again on our way out of the station, and I think you can tell by the look on our faces just how excited and happy we were. And if all that weren’t magic enough, I received an email from my agent the next morning (while waiting for Suzy to come over for tea and scones—she was staying at a hotel was close to my house) that House of Anansi was going to make an offer on my book.

A year later, I am still trying to be more comfortable with having no expectations, just living in the moment I am in, which is easier to do in a world where I know good things happen sometimes. I just finished up the final pass for my new novel, now called DEFINITELY THRIVING. Marissa is reading it now from Los Angeles where she is busy at work on exciting things in preparation for the release of the Apple TV series based on her novel LUCKY. Suzy is reading it too from her home in Regina, where she’s spent the past year working on her own next book, and SUZY THINKS MY NOVEL IS GENUINELY FUNNY (Woot!).

The writing life is full of up and downs, and I’m realizing that there is actually no level of success that ensures an end to that. But in the meantime, there are magical people, friends to celebrate, and—in our own books, and real life—wonderful twists that can catch us unaware.

January 13, 2025

Ways To Read More in 2025

I’m of two minds about this post. First, I am allergic to the ways in which online writing has become so prescriptive, which means that online reading has become about emphasizing the ways in which we’re all doing it wrong and are in need of optimization. This is everything I’ve been turning away from as a writer and a reader, and what I’m abjectly refusing for this new year. If all this striving was turning us into happy and satisfied beings, I’d be okay with it, but it’s not. (A book I read last year that clarified this was Meditations for Mortals.)

HOWEVER (and this is self-serving as someone who earns a living from books and publishing and also dreams of a world in which literature occupies as much cultural attention as reality television) aspiring to read more is a resolution that’s different from trying to lose 15 lbs, develop an entirely different personality, or make a fortune in a multi-level marketing scheme. I also think it’s an aspiration that, if you’re realistic, fair and easy on yourself, really can make you a little bit better off.

Further, I read 214 books last year, which is more books in a year than I’ve ever read in my life, so I know what I’m talking about. And I’m sharing the number 214 because having read so many books in a year is actually the single most impressive thing about me; I don’t run marathons, I don’t have pretty fingernails, I last won a literary prize 20 years ago for a story that was terrible—so please just let me have this one thing. If your own reading goal ever seems paltry compared to mine, remember that comparison is the thief of joy and you do you… but how about doing you with a just a little bit more time for reading?

Here are my tips for how to find some.

1) Get Your Blood Checked

This was a game changer for me! I went to donate blood last January and was refused because my iron count was too low, which was not surprising since I’d spent the last six months (during which I was otherwise well) struggling to get out of bed in the morning, feeling very much like a hibernating bear. So I started taking iron supplements (Floradix, the vegetarian variety that doesn’t cause digestive issues) and waking up an hour earlier (um, not too early—I will never been an early riser) and I decided to spend this bonus time not getting out of my cozy bed, but picking up the book on my bedside instead. Which is so much time for reading, not to mention a really lovely way to start each day.

And so if you, like me, are not particularly youthful, and you’re one of those people whose eyes fall down every time you curl up with a book, getting bloodwork done might be something to consider.

2) Put Your Phone (Far) Away and Delete Socials

It’s much easier to wake up in the morning and pick up a book if your smartphone is out of reach. Mine charges overnight far away from my bedside, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I’ve also deleted the only social media app (Instragram!) that had remained on my phone, which has freed up so much space in my mind and hours in my day. I still use social media on my desktop, and download Instagram once or twice a week to post and share other people’s posts in my stories (which I can’t do on the desktop) but I delete the app once I’ve finished.

And yes, it means I’m a little less connecting to the quotidian details of the 3000+ people I follow on Instagram, but maybe that’s okay…?

3) Find Your Desert Islands

Once your phone is out of reach, you’re on your way. I like to find opportunities to be stranded someplace with a book and nothing else for distraction. The bathtub is my favourite place for this, but so is the coffee shop at the block near where I drop my daughter off at an extracurricular every week for an hour and a half. Along those lines, going out for lunch with just a book for company is one of my favourite indulgences. If nothing else, I try to read between 9pm and 11pm every evening when nothing else is going on. If you tend to spend that time streaming television, maybe consider designating one night a week for reading instead? (I rarely watch TV, which I do think [in addition to my robust iron counts these days] is the most important answer to the question of how I find the time to read.)

4) Make It Easy

Reading doesn’t have to be a chore. It should actually be fun. And while some people’s idea of fun is Middlemarch or War & Peace, accepting the reality that you’re not such people (if you’re not such people) will go a long way toward having your reading habits take hold. Which is to say: read the kind of books that make you relish the turning of pages. Yes, reading widely and challenging yourself is a great way to read, but if you’re striving to read at all, making the experience purely a delight will help a lot. Read short books! Quit books you’re not enjoying. Ignore the books you think you should be reading. Don’t be afraid to trust your tastes and instincts, and to steer your own reading ship.

5) Build a Framework

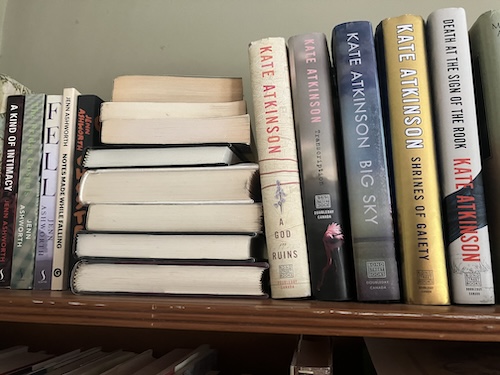

And along those lines, I like a reading project. I’ve taken on a whole bunch of these this year (more to come in my January essay for paid subscribers), one of which is #WinterofStrout, as I go back and read every book Elizabeth Strout has ever published. I reread all of Madeleine L’Engle’s Austens series back in 2019. In March 2020, which I found it hard to read anything, I found my back to books by rereading Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie books.

If there’s something that interests you, an author you’ve been meaning to get around to, any particular kind of book—books set in a certain place or time period, award-winners from a particular decade, a particular segment of the books already waiting on your to-be-read shelf, anything that might seem fun, and feel good and satisfying—steer your reading ship that-a-way, and let the literary magic happen as those books weave their way into your day-to-day life.

November 4, 2024

25 Hours

The day the clock falls back is my favourite day of the year—I’ve written about this over and over. How the extra hour is, of course, time to read in, which matters especially at a moment in which I seem incapable of reading less than five books at a time. It means that I woke up yesterday morning and proceeded to spend the next hour in bed, finishing THREE DIFFERENT BOOKS (and I’d just finished another the day before). And then after such a feat of completion, I started reading another book that was short enough and good enough—Susie Boyt’s LOVED AND MISSED—that I managed to read the whole thing in under 24 hours. And what a 24 hours it’s been. My family’s schedules obviously out of sync with the time change, which meant that dinner and all evening duties were concluded before 9pm, which is unheard of in my household. Everybody else was tired and went to sleep, but I just returned to reading, and the luxury of this time and this focus was such a pleasure to behold. (Again, it helped that I was reading a book that was so very excellent.)

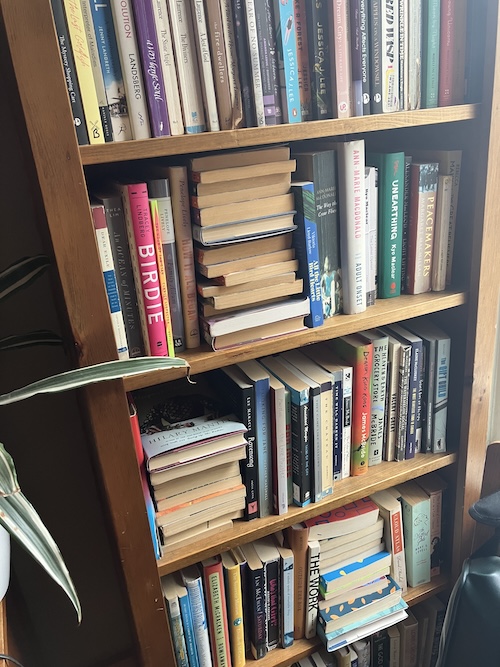

One of the many book piled on my bedside table right now is Meditations for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman, who writes in one reading about the reality of information overload. “How do you choose what to read?” somebody asked me recently in a DM, in the context of all the seemingly infinite books out there in the world, and the point of Burkeman’s book is the finite nature of human experience. And Burkeman offers the image of a river, how as readers what we do is dip into the current and pick out what we can, what we want to. No one is ever going to read all the things—there are not enough extra hours in the year, even though I’m doing my best to make a dent, for sure!—and nobody should feel bad for their failure to, and this was such a relaxing way to think about the stacks of books on various surfaces around my house that are constantly, dangerously, threatening to topple over.

September 18, 2024

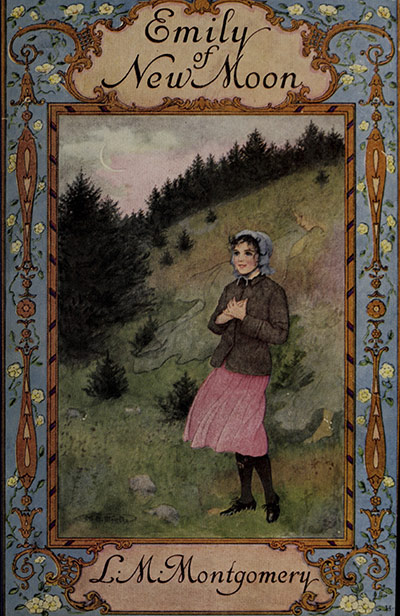

On Emily-Splaining

People are weird on the internet. A couple of weeks ago, a comment turned up on a post I published more than four years ago about rereading Emily of New Moon, and this commenter was not having it, unleashing a diatribe of scolding. And not even for having stolen a copy of the book from my school library (which would have been fair!), but for having understood Emily within the context of Anne, and for judging a book by its cover. Of my trouble with the drowned barn cats, they wrote “If your delicate modern sensibilities are disturbed by this, well — you need to read other books.” OMG, SERIOUSLY, COMMENTER: DO YOU KNOW WHO I AM?? I have read ALL THE BOOKS. And then they proceeded to answer all the questions I’d posed in my post, which was really really annoying since these were actually the questions I’d had about the books when I was 9, and I’d actually worked most of them out by now. It was more than a little PATRONIZING.

But I’m not bringing this all up so you can be indignant along with me. (Okay, I am A LITTLE BIT). But instead because I also really understood where this annoying person was coming from—and perhaps this is why I’m especially indignant because I’m just the same. To ASSUME that you could explain L.M. Montgomery to ME! And I understand that there is a whole community of Montgomery scholars and historians, and they even have a society, and that’s fine, but I’m still quite sure that nobody there could have the connection to Montgomery and her work that I do. I’m entirely wrong about this, just in case that needs stating, but it doesn’t matter, because my connection to Anne and to L.M. Montgomery’s story feels so fundamental and so personal that it’s impossible to imagine that anyone else could precisely know what I’m talking about when I mention it. And of course they can, but there are parts of the story that were mine alone—my Anne of Green Gables clothespeg doll I bought in Fenelon Falls, the Anne of Green Gables Treasury I absolutely coveted from this folksy store at the mall and saved up for. When I was Anne for Halloween, the copies of the novel that were gifts from my Grandma. The time we were out on a boat with another family, and I asked my mom how Anne and Gilbert managed to make all their children because, according to Anne of Ingleside, they slept in separate bedrooms…

If that commenter is anything like me, they are possessive of their Emily. Other people might have their own Emily stories, but it’s not the same, and it’s the strangeness of these characters we got to know in our most formative years, the way it felt like they were speaking directly to our souls, but other readers were picking up the very same signals. The way that reading seems like such a solitary thing, a private universe, but there are so many of these, and the shock of realizing the connection may not have been quite so intimate after all.

September 9, 2024

My Stacky Authors

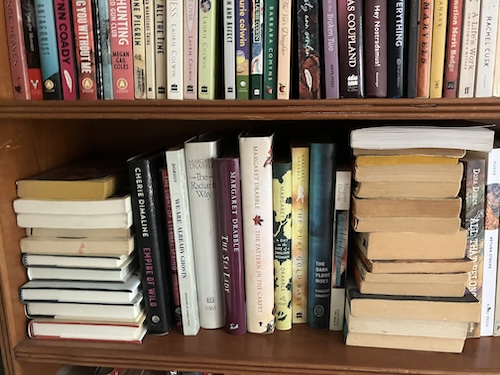

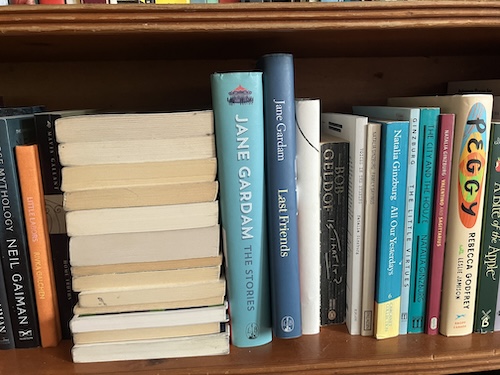

This weekend, Kate Atkinson joined an esteemed group of writers when her latest, Death at the Sign of the Rook (review to come! RAVE!), found its place in my personal library, and I determined that it was time for Atkinson to get stacky, which is what happens to authors who I like too much. And I actually kind of hate it, that I don’t get the pleasure of seeing books by my favourite authors with their colourful spines all in a row, but space is at a premium and I have to make it work (although my husband did recently suggest replacing one of our bookshelves with a taller one! SWOON!), but the only way I can accommodate the necessity of having 13 books by Atkinson on my shelf (does not even include the two of her earlier novels that I didn’t love and got rid of, which rankled the completest in me, but what can you do) is by stacking a bunch of them into a pile.

Which frees up so much space!! Room to breathe!!! Room for more books!! To be one of my stacky authors, really, is one of the largest literary compliments that I could pay you. You’d be in the company of Kate Atkinson, Joan Didion, Margaret Drabble, Jane Gardham, Penelope Lively, Hilary Mantel, Sue Miller (SO MANY L and M AUTHORS!), and Iona Whishaw.

Carol Shields is on the list now (there is more room among the Ss), for the next time shelf space gets tight.

June 12, 2024

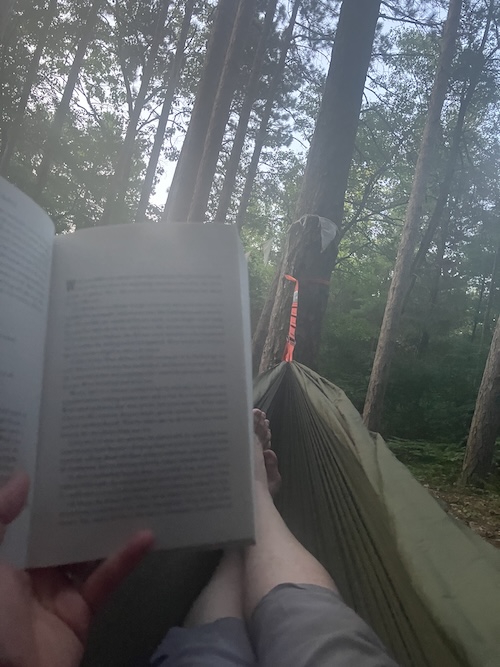

Weird Reading Place

I returned Kelly Link’s THE BOOK OF LOVE to the library today, unfinished and with mixed feelings. I managed to read just over half of it, and if I could renew it, I think I would, but I can’t renew it (there is a line of people with holds who are waiting to get this GIANT novel [600 pages!] into their hands) and there is also a threshold of caring enough to get to the end that I just can’t seem to cross. Part of it is the tone of the book—it’s so even. And I don’t hate that, of course, and “uneven” is certainly a criticism, but yes, there is a steadiness to the narrative that’s the opposite of “gripping” or “exciting.” I’m also not deeply invested in the plot, which is all about magic, not my kind of thing at all (my experience of this book is similar to this one: “I finished it and I’m ready to tell you about it, because it’s Not My Sort of Thing, and yet I’ve read all 625 pages of it, even though it’s a genre I rarely touch. I’m even sort of mystified about why I ended up buying it, in hardback,” except that she finished it and I didn’t). If I could keep the book forever, I’d likely get to the end eventually, but that’s not a screaming endorsement, and also the book seems like it’s weighting me down a bit. I’m still in a weird reading place because I can’t go all-in on a 600+ page book I’m not that bothered about (this would likely kill me) so I’m reading another book as my “main book” but it’s really not not doing it for me, and I’m reading ANOTHER book (The Blue Castle, by LM Montgomery) in preparation for my June substack essay, but FOR SOME REASON IT FEELS LIKE MY ATTENTION IS SCATTERED. (I am also reading ANOTHER book, Shawn Micallef’s STROLL, which I am absolutely loving, and reading more avidly than I’d anticipating—I was expecting to read this book as a kind of walking guide, but it’s turned out to be an absolutely compelling, fascinating book to read when you’re not going anywhere all all). I’ve been more reading books quietly too, advanced reader copies (which usually aren’t my thing!) in preparation for Season Two of BOOKSPO, and that’s been good, but in general it seems like I’m reading 14 books at once and not getting anywhere with them, in terms of depth or toward and ending. And not being enthralled by a book is one of my least favourite states of being. I am not myself when I’m not reading something I love—it’s like going without lunch. It doesn’t help that it’s June and EVERYTHING IS HAPPENING and what I really really need is an afternoon in my hammock.

June 6, 2024

Message From the Middle

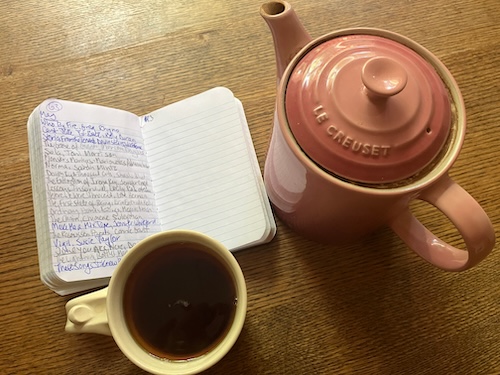

In December 2017, under the influence of Vicki Ziegler, and after much fretting and deliberating (was it really necessary to track my reads? Couldn’t I just read books like a normal person?), I finally started tracking the books I read in a notebook, which turned out to be the very best thing, and this week I reached the milestone of getting to the centre of my book of books. THESE THINGS I KNOW BY HEART, by Erin Brubacher, the 83rd book I’ve read this year, and the 1083rd book I’ve read since December 2017 when I began the notebook with LITTLE FIRES EVERYWHERE, by Celeste Ng. And I am so grateful to have this record, which is useful when anyone asks me what I’ve read lately (like I ever remember?) or I want to take a trip back in time to recall what I was reading on vacation in July 2019 (MIRACLE CREEK, by Angie Kim, PACHINKO, by Min Jin Lee, THE LAST ANNIVERSARY, by Lianne Moriarty), or later that summer when I was reading THE NEED, by Helen Phillips at Kew Beach, or the books that counted down the days before the world broke in March 2020 (POLAR VORTEX, by Shani Mootoo; DISFIGURED, by Amanda Leduc, all my little obsessions (when I reread Madeleine L’Engle’s Austin series in 2019, or 2018 when I read everything by Amy Krouse Rosenthal, falling in love with Sue Miller and reading EVERYTHING), the forgettable books that were forgotten, the UNforgettable books whose reminders make me feel so much (reading THE BURGESS BOYS while eating breakfast in a hotel lobby, how I couldn’t put it down). It’s not about the numbers, though the numbers are interesting too, but instead about the stories in the experience of reading the stories that the notebook has recorded, where over six years has taken me, bookishly and otherwise. And the other half of the notebook, its pages still blank. All that possibility, patiently waiting for each line be filled.

April 3, 2023

New Book Quiz!

Which one of these fantastic books is your next favourite read?

Take my new quiz to find out!

Yep, I’m back with some literary matchmaking after far too long and I’m THRILLED to be setting readers up with some books I’ve loved lately…