August 15, 2019

Immediacy

I’m really terrible at Instagram. Or rather, I’m totally amazing at Instagram, were Instagram a blog circa 2004. I share too much; cannot hold back; it’s sometimes poorly lit and totally unfiltered—well, except the photos of me in the yellow locker room first thing in the morning, which are what filters were made for, aesthetics are not central to the experience, the colours clash, and my face is everywhere. You either like it, or you don’t.

But I love it. For me, my Instagram is an extension of my blog for sure, the place where my most mundane and curious content has migrated. It’s a scrapbook of my days, my moments, and it’s also got the community component that blogs had circa 2004, people I’ve never met who feel like my friends. And there are certainly things I’ve posted on Instagram that have turned into actual blog posts, but just extended. Sometimes Instagram is where the thought begins.

It’s the immediacy of Instagram (and blogging) that I love, the Insta-ness. It’s the insta that makes the whole project worthwhile. Although there is actually very little that’s insta about Instagram anymore, now that the feed is algorithmic instead of chronological, and we’re all supposed to schedule our posts for optimum brand engagement. But I refuse to be a brand, and keep on insisting on being an actual, real live and moderately-flawed human being. Not for everyone—and that’s okay.

How can you even schedule a blog post, or an instagram post? For me, blogging has always been about the moment, capturing the atoms as they fall (to paraphrase Virginia Woolf). Right now as I’m scrambling to write this down with twenty minutes to spare before we tumble out the door and onto the subway to meet friends for a picnic. Context is everything, and so is (I suppose) exuberance, which is what leads me to post nine photos in a row in a single afternoon, an effort to (impossibly) capture every single angle.

This green, this light. How it was exactly. (And now it’s gone. But not entirely.)

August 7, 2019

Get Excited and Make Things

Once upon a time, we had a sign on our fridge that said, “Get Excited and Make Things,” and I have no idea where it came from, but apparently the meme originated in a 2009 Will Wheaton blog post, and the sign was stuck on our fridge with a magnet for years. Coming down at some point, but the sentiment lives on, and I think it might have become our family motto, if the enormous piles of stuff on my children’s crafting table are any indication.

But it’s a sentiment I believe in, and one I clung to as I entered 2019 feeling somewhat dispirited, mostly because I didn’t have much to feel excited about. Excitement is my driving force, and I didn’t know what to do with the year that lay ahead, in which no plans and schemes were being hatched, so I decided to make some. I went back to the blog, remember? And I made Briny Books and Blog School (with the help of my husband who built the websites for both—it’s a family motto, remember?), and now my little world is overflowing with things to be excited about, and I’ve got butterflies in my stomach perpetually.

And this is what blogging is all about, right? It’s about making something out of your stories, experiences and ideas, a DIY aesthetic, making the whole thing up as you’re going along and learning as you go. It’s being a blogger that has given me the mindset to take on these new projects this year, figuring it all out as I go along, to not know the outcomes, but to have some faith in the path forward. Let’s see how it all turns out, is the blogger’s approach, which requires attention, curiosity, and a capacity for growing, learning, and—ideally—being excited all the time.

August 5, 2019

Keeping Blogging Weird

In the spring, @hkpmcgregor recorded an episode of Secret Feminist Agenda about “Keep Podcasting Weird,” and I’ve thought about the episode a lot in relation to blogging and book blogging. I had been blogging about books for awhile when publishers started sending me review copies in 2007ish, and while I was grateful for their attention and consideration, I lament now what it did to my blog. Because it turned my blog into a blog that looked like everyone else’s, and at the time I even thought that meant I was finally doing it right. But what gets lost—attention to obscure novels, my own unique perspective, the indulgence of my own curious avenues. It’s also just not as interesting to be blogging about exactly the same books that everyone else is, and what exactly is the point of this pursuit, beyond contributing to online homogenization.

I’d started blogging about books while I was a graduate student, so I’d been writing about Virginia Woolf and Victorian entomologists, and I was obsessed with the works of Margaret Drabble and Laurie Colwin…and then all of sudden here I was reviewing the new Ian McEwan. Yawn.

From my new online blogging course, Find Your Blogging Spark

More than ten years on, I’ve learned the virtues of keeping it weird, who wins when we do (hint: it’s everyone), and what a more interesting place is the blogosphere and #bookstagram when we make space for novels purchased for a dime at a provincial park camp store. Books you decide to spend that dime on because of a description that begins with, “Only the pub and the pet shop are still inhabited in the boarded-up wasteland of Crow Street Southwest London…”

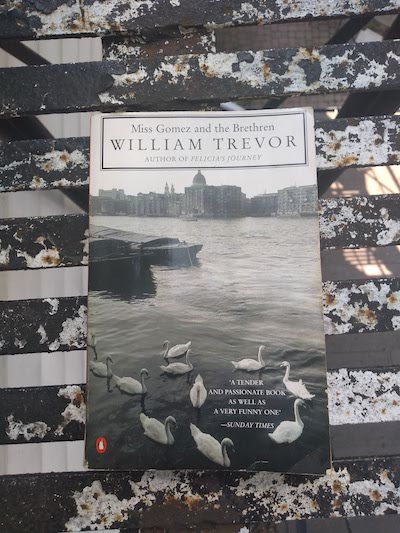

I spent much of this long weekend reading Miss Gomez and the Brethren, an early novel by William Trevor, whom I’ve never read before, and the novel reminded me of Muriel Spark, that curious midcentury mix of slightly old fashioned and shockingly sly and subversive at once, with an outsider’s view of Englishness.

I absolutely loved it, and have been thinking a lot about serendipity, partly because the book is about just that (although in a darker and less whimsical sense) and also because of the odds of this book and I finding each other, the most perfect literary match. Whoever left this book—which I’d never even heard of—in the camp store so that I would find it because we’d ducked in to get out of a thunderstorm, lingering over ice cream cones to avoid going out into the rain. Someone left it and I happened to find it, picking it up because William Trevor’s on my long list of authors I’ve been meaning to get around to reading, and here was one of his books in my hands, the kind of summer reading magic that is impossible to manufacture, but I’ve been grateful to be a beneficiary, and have this book be part of a wonderful long weekend.

July 31, 2019

Stop Waffling, and Write

I finally read Brigid Schulte’s essay in The Guardian, “What is women’s greatest enemy? Lack of time for themselves,” an essay I’d seen many people sharing online last week. And to be honest, once I got to it, I found the piece a bit…slight? Understanding why it had resonated with so many women for sure, but it also frustrated me, and made me impatient. I wanted more. I wanted something less waffley (no offence to waffles) and less cribbed from A Room of One’s Own, because it’s been 90 years, and surely we can do better than, “What would happen if…” and thought experiments about Shakespeare’s sister.

(What might you have written had you not sat down to write the piece about how women don’t take enough time to sit down and write?)

I’ve spent the last few weeks completing the modules of my blogging course, whose goal is to deliver women the confidence (the nerve?) to carve out their own little space online, to emphasize to them that their voices matter and so do their stories, and that the world needs both these things. I’ve written 25,000 words that I’m proud of and excited to share very soon that I hope will inspire and motivate people who are blog-curious or at least need a little jolt to get their blogging spark back…but at the heart of it all there really is just one point, and it’s this one: You just have to do it.

And you know what? We can blame the patriarchy. (We definitely SHOULD blame the patriarchy. See Toi Smith: ‘Let’s stop calling it “mom guilt” because that’s bullshit and not actually a thing. Let’s start calling it what it really is: internalized patriarchy, capitalism, and white supremacy which has conditioned women to believe that once we become a mother our pleasure isn’t ours, that our joy isn’t ours, that our creative force isn’t ours, and that our time isn’t ours.”)

But all this means is that when you finally do sit down to write, what you’re doing is more radical, awesome and profound than you might initially understand it to be—which only makes it all the more important that you actually sit down and write. Telling yourself that you’re not writing because you don’t take time for yourself is a decision you have made, and it’s kind of boring. It’s also like telling yourself that don’t write because you’re a perfectionist, or that you don’t write because you have a job, or because you have kids. (To be fair, if you’re not writing because you have kids AND a job, I get it. Though there comes a point when “having kids” stops being an occupation that takes up every ounce of your soul and your life.)

Because there are so many people who face these hurdles, but leap over them and write anyway. There are so many women who do make time for themselves and for their art, even if we live in a society that conspires to make them feel guilty about those choices. So to stare wistfully into our teacups and lament the choices we’ve made to limit our creative experiences (honestly, you could let that call from your mechanic go to voicemail) because that’s just how it for women, it’s what we do, is essentialist and very annoying.

It’s also just another excuse to avoid doing the thing, and Brigid Schulte gets it exactly right when she writes, “I wonder if that searing middle-of-the-night pain that, at times, settles like dread around my solar plexus may not only be because there’s so little unbroken time to tell my own untold stories, but because I’m afraid that what may be coiled inside may not be worth paying attention to anyway. Perhaps that’s what I don’t want to face in that dusky room I dream of.”

The biggest challenge lies in not finding the time to write, but in staring such fear in the face. But it’s possible. With the knowledge that even if you fail, you’ll be so much further along than you would have been if you hadn’t tried, and also that you will never ever be better than you’ll be if you start practicing right now.

March 11, 2019

Why I’m waiting for your next blog post

(I sent the following message to writers signed up for Blog School: Pickle Me This mailing list last week, but I think you deserve to read it too. And if you want to sign up for Blog School updates, you can do so here AND receive a copy of my free download, “5 Prompts to Bring Back Your Blogging Spark.”)

For many bloggers, the biggest impediment to actually getting to PUBLISH is the idea that maybe no one’s reading, so what even is the point? And my smart answer to this has always been that you should be blogging like no one is reading anyway—so if no one actually is reading, doesn’t that just mean you’re doing it right?

My non-glib take on this is different, however, because I’ve never been more hungry for good things to read online, in blog posts in particular. It’s why I’ve started “Gleanings”, a weekly series (also available as a newsletter) where I collect links to all the fascinating pieces I’ve come across on the internet—articles, essays and blog posts that made me think and/or delighted me. I’m so grateful to writers who continue to craft smart posts, make thoughtful arguments, and introduce us to excellent people, places and things, all of this countering the toxic discourse we so often encounter online that’s lately rearing its ugly head in the real world. I continue to believe—because I’ve seen the evidence—that with our own small corners of the internet, we really can make the world a better place.

And because I know that crafting meaningful blog posts is important to you—you were curious enough to download my “5 Prompts to Bring Back Your Blogging Spark” after all—I wanted to check in and encourage you to keep going. If you haven’t updated your blog in awhile, now is the time to do it. If you’ve written something lately that you’re proud of, I hope you’ll leave a link below in the comments so I can read it, and so my readers can read it too—because I’m not the only one who’s craving great posts to read.

So many of us are looking for goodness these days, but blogs are an opportunity to get proactive and actually make some. I’m really not kidding when I tell you that I’m waiting for your next blog post, and I promise I’m not the only one.

March 7, 2019

Why Your Own Small Corner of the Internet is Going to Make the World a Better Place

I spent last week gathering signatures for a petition among parents at my children’s school calling on our government not to increase class sizes—which is a call that everyone was happy to get on board with. It was the “duh” of petitions, but even still. “You’re awfully optimistic,” one person remarked as he signed it, but I’m really not. I understand that a majority government with short-sight and an ideological agenda is probably not going to be moved by a bunch of signatures in a riding that didn’t even vote for them not to make cuts to our already under-invested education system. But this still doesn’t seem to me like a good enough reason to sit back and just let it happen, to do nothing. Even if the outcome is the same, the outcome won’t be the same, because there will have been resistance. The fight always matters, even in the rounds you don’t win.

It was probably twenty years ago when I had a revelation about my ambition to become a writer, which was that even if I never succeeded in my goals, merely striving for them would end up taking me on a different and further trajectory than if I hadn’t bothered. And maybe what I’m trying to say here is that I’m comfortable with the notion of futility, or perhaps that there is no such thing. I believe in small things, and how they lead to possibilities, and I’m going to keep on tending my own garden, because it’s a thing that I can do.

Although by tending my own garden, I don’t mean retreating from the world, planting a row of tulips behind a barbed wire fence while the world falls apart outside. I don’t mean walls, because walls aren’t real. If someone’s not okay, then no one is okay, because there is indeed such a thing as society. And there has never been a more important time to be connected with society, with community—which is why I spent last week gathering signatures for a petition (on paper, with pencils, and everything). Sometimes social media can give us the illusion that we’re being political, making a difference, but I’m starting to think that it doesn’t count. I’ve been making an effort this year to replace to my Twitter engagement with real things—blog posts instead of tweet threads, sharing links to things I love in a newsletter, walking around the school yard and talking to people in my community instead of writing obscenity-laden tweets to idiot politicians who are never going to read them which is really only an exercise in screaming at the sky.

What I mean is that I continue to insist that my voice matters, however in a small way, and so do the choices I make and the causes I show up for, the principles I instil in my children, and my decision to live with integrity and stay true to the things I believe in even as integrity and truth don’t seem so fashionable these days.

And lately I’ve been tending my own garden especially by going back to the blog, planting thoughts and ideas and watching them grow, and even watching them spread as other people read and respond and write posts of their own. I continue to insist that blogs matter too, and that the internet needs blogs more than it ever did—a place where there is thoughts instead of noise, where the people aren’t bots, where there is room to expand and explain and even change your mind. Blogs are important in 2019 because they aren’t underlined by corporate interests, because what parts of them we read aren’t determined by algorithms, because of their focus on language at a moment when politicians are making meaninglessness into an art form, because of their obscurity even and how they give us the freedom to explore off our own beaten track, because they’re not part of an industry that’s flailing, dying, desperate. There’s nothing desperate about a blog.

To blog is to be hopeful—that words matter, that someone is reading, that small things make a difference.

“You’re awfully optimistic,” one might suggest in response to this post, but again, I’m really not. I just believe that doing what little you can is always better than doing nothing. I don’t think that people understand enough about their own power—drop off a loaf of a banana bread at your neighbour’s, or shovel their driveway, and you’ve transformed your community into a place where such things can happen. How we spend our days becomes how we spend our lives, and who and what we are (online and off) becomes the world.

January 28, 2019

Can You Tell I’m Turning 40?

I bought a Brené Brown book a couple of weeks ago, in case it wasn’t totally obvious that I’m turning forty in the next six months and am currently experiencing a mild case of the kind of existential crisis that necessitates some reinvention. Although I must confess that I am not finding the book (Daring Greatly) to be such a revelation. As anyone who has read my blog for five minutes can attest, I don’t have a problem with being vulnerable, and perfectionism has never been a force that I’ve had to go to battle with in any part of my life. Instead, it’s with “imperfectionism” that I’ve found my strength as a creative person during the last decade, as a blogger in particular. Which is mostly the art of being a human—and I excel at that. (We all do.)

But what has prompted my mild crisis is the dawning awareness (which I alluded to in my ambivalent post about your stupid bullet journal) that imperfectionism has its limits too, and that it’s possible to be using it as a kind of a cover, a retreat. An excuse to not to bother to be any more ambitious, because that’s just not my brand, man. Because brands are not my brand, man, which is fine, but what if part of the reason I’m so comfortable being merely good-enough/imperfect and not having to make the effort is not so much because effort is distasteful, but because I’m afraid of trying and failing and having everybody see? Because I’m scared of trying to figure out a new path forward, of stumbling and making mistakes in public view. All those things that I’ve been able to counsel writers through with blogging—I’m comfortable showing my process here—but I’ve been hesitant to apply the same lessons in other areas of my life. Now I’m turning forty, however, and I think it’s finally time.

In the last ten years, without deliberateness and mostly due to persistence, luck and a passion for books that is as organic as gut bacteria, I’ve been able to create a unique place for myself as a writer, as a reader, as a reviewer, and a literary critic. It’s a place that I’m amazed by now, by the opportunities and connections I’ve been able to experience, and I’m grateful for all of it. But this place is also a tricky kind of place as well, because I’m not just a reader, I’m not just a writer, I’m not really an editor, I’m not just a blogger, I’m not simply an impartial critic, and I’m not a proper journalist either. And my failure to fit properly into these pigeonholes (in a newspaper/magazine/publishing industry that has fewer and fewer opportunities to offer all the time) has bothered me, and made me feel like I was doing everything wrong sometimes, made me feel like the space I’ve come to inhabit as a writer and a reader is the problem after all.

But it’s only a problem if I’m sitting around waiting for other people to deliver me opportunities, you see? Which is why I’ve decided on a new approach for a new year and a new decade, why I’ve decided to finally begin work on projects I’ve been wanting to do for years, why I am going to start being more deliberate and entrepreneurial in my professional life—because the unique place I’m in also offers opportunities. And my blog will be the centre of that—it’s been the centre of everything. Part of my distance from my blog last fall was because it felt like undervaluing my thoughts and ideas to be publishing them here rather than on a more legitimate publishing outlet. But then why wasn’t I feeling that way about the thoughts and ideas I was posting to Twitter and Facebook? This question clarified so much to me. What if, instead of composing Twitter threads and having Facebook arguments with your weird cousin, I was posting here instead? The back-to-the-blog movement, as I wrote the other week. It all coalesces here. I still love writing for magazines and newspapers, and the opportunity to work with editors, but what if I stopped looking at blogging as a kind of defeat. What if I worked to build my audience here, to build my newsletter, perhaps to have non-annoying advertising and make some revenue there? To build on something that is mine.

I am so excited about blogging right now. Yesterday I said that to my husband, about how on Sunday I look out at the week ahead and all the things I plan to write about—I wasn’t feeling so inspired a few months ago. But I really am now, with a renewed appreciation for the kind of space a blog can be, and a certainty that we need blogs more than we ever have—which makes it advantageous that I’m finally planning to launch an online blogging course in September. The Pickle Me This Blog School is in the works and I look forward to applying what I’ve learned from nearly twenty years of blogging and eight years of teaching blogging to show people how to create a blog that fits their lives and even makes life richer.

I’m also going to be working to engage people to connect with writing and storytelling in other ways, to inspire them to find and make time/space in their lives for books and reading. Partly through what I’ve always done via my blog and other platforms, but with other projects and initiatives as well, plans I’m hatching now. And I hope that you’ll be excited (and inspired!) too as it all starts to come together.

January 18, 2019

The Back to the Blog Movement

“I blog to make sense of the world,” is the way that I’ve always explained my attraction to blogging, the way that I use my blog as a workbook, a scrapbook, part of a process toward understanding. But in the last couple of years, the world hasn’t made very much sense at all, and in ways great and small, I’d started to suppose that blogging was futile. Certainly people weren’t reading blogs anymore, and enticing readers to do so required wading into the mires of social media, where standards of behaviour were abysmally low and one gets the sense that with every scroll, the world becomes a place that’s slightly worse. But still I kept scrolling. “I’m not getting off twitter,” I’ve said on more than one occasion too late in the evening, scrolling, scrolling, “until the world becomes a place that I can understand again.” But it turns out the Twitter is even more futile than blogs are for sense-making, plus it’s passive, hijacked by capitalism, stupid algorithms, and rife with violence and abuse.

Last fall I experienced a distance from my blog, which I continued to update, but mostly with news and book reviews. I wrote fewer personal posts, though that was partly because Instagram really has taken over as my receptacle for quotidian things. I wrote less about my children, but that was more because they no longer exist in the world solely as extensions of my existence. I didn’t write many of what have always been by favourite posts, random explorations of connection-making, experiments in thought and narrative. I was always busy with paid work, and I was writing a novel, so much so that I didn’t worry so much about what was happening with my blog. But I was beginning to lose the habit of writing a blog, and the habit of thinking like a blogger, which is going out in the world with my eyes open to story and connections and questions. In losing some faith in the world, I’d also lost faith in those questions and connections’ ability to bring me closer to answers, which is a self-fulfilling prophecy when the end result is endless scrolling on Twitter.

The blog posts I was writing last fall didn’t always feel satisfying, didn’t seem to illuminate my understanding. I think I was feeling dispirited and and a little bit sad, writing posts about the crime of underfunding public education or about what it was like to have published a novel that was not a commercial success. By October, it had been a year since I’d last taught a blogging course or workshop, the longest break since I’d started teaching in 2011. “And really, I’d be happy never doing it again,” I remember saying, because I didn’t feel comfortable claiming to be a blog authority. Having forgotten, apparently, the cornerstone of blogging form, which is that having questions is far more important than having answers, and that no one is an authority ever.

But I did remember one thing I always told my blogging students, which is to write your way toward any answers you’re seeking. So a random post about a missing hat, or another about how I was looking for a babysitter. These were posts I wrote because it felt good to be writing and employing the first-person perspective again, though I wasn’t sure what they all added up to. In some ways, it felt like I was learning to be a blogger all over, learning to be uncomfortable. Questioning what this space was for, what stories I was telling, and what my voice was. So what’s the point? There usually wasn’t one.

Then in late December I spent a week and a half offline.

And when I returned to the internet in the new year, I realized there wasn’t much about the internet that I missed at all. I still liked Instagram, but that’s only because it is essentially a blog. Twitter brought me no pleasure. Facebook seemed like a waste of my time, and I would leave the site altogether…except for the people I like there. But then, if those people really want to hang out with me, can’t they come over to my blog? I’m really not hard to find—and suddenly the possibility this online space permits me seemed wide and exciting. I felt hopeful about life online for the first time in a long time, because I can conduct it on my own terms, in my own place. What if we stopped spending our time on websites owned by multi-million-dollar corporations that are demonstrably making the world worse all the time? What if the forty-five minutes I spent this evening having my brain turned to jelly trying to fathom the perspective of some guy on Twitter cheering on a right wing politician had been spent on anything else? What would life online be without the bots and the manufactured outrage, stupid algorithms, the trolls and the racist uncles? Totally meme-free, with unlimited characters, and nobody’s sharing any fake news article created by a shady network in Outer Siberia.

It would be a blog, of course. Right back where we started in Web 2.0, with stories and voices in a range that the world has never before been able to read, voices not in chorus, but not so polarized either. Connected, but not in a thread, more like a quilt, if we’re thinking in textiles. Niche onto niche, something for everyone. With room enough for stories, and questions, and nuance, and reflection, and changing your mind. And also for changing the world, in the small and subtle ways that blogs have always mattered—turns out I’m not ready to give up on that one just yet.

February 16, 2018

(Not) Getting Paid to Do What You Love

I saw the worst thing ever two days ago, which was an Instagram account where one photo included the following caption: “Happy Anniversary to my adorable hubby! I love the life we created together including our fantastic son:. #ad”. Another photo was of a bowl of soup and a link to a post about how blogging had allowed this writer to find her passion and make it her career, and that passion was for, apparently writing posts about canned soup, and there’s even a giveaway to win $500 so you can get started on following your dreams and writing about soup too. “Love what you do! Keep chasing your dreams!” chimed her commenters, who are surely part of a weird scheme of override Instagram’s algorithm, because I can’t think of any other reason so many people loved the soup post. Which didn’t even mention the soup, which is a travesty, because I love soup, and could read about soup for days.

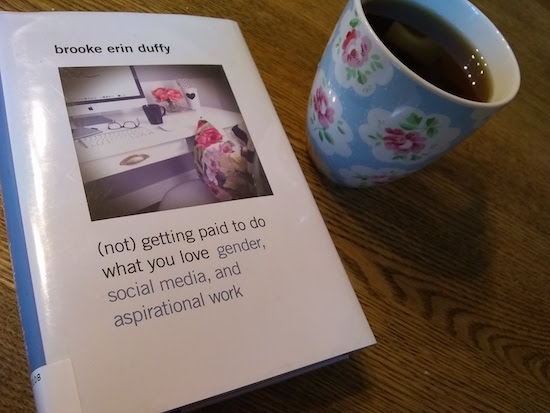

This Instagram account seemed unreal in more ways than one, and was particularly resonant for me just one day after I’d finished reading Brooke Erin Duffy’s (Not) Getting Paid to Do What You Love: Gender, Social Media, and Aspirational Work. Loving what one does and chasing dreams were a recurring theme in Duffy’s interviews with fashion bloggers, Duffy’s thesis being that there’s a lot of chasing and you sure better love what you’re doing because you’re probably not going to get paid for it, except maybe with soup.

I heard Duffy talk about her book a few weeks ago at the McLuhan Centre’s Monday Night Seminar Series, “MsUnderstanding Media,” and it was a fantastic discussion. One that was right up my alley in lots of ways, and not, at the same time. Or at least that’s what I kept telling myself. Duffy’s ideas about aspirational labour in the fashion blogosphere not entire applicable to where I’m at in book bloggerdom, but still discomforting in a few respects and her book would end up problematizing my own work and ideas in an interesting way.

But still. There are many blogospheres, I remind myself. There are many book blogospheres, as there are many fashion blogospheres, I presume. And as I type this now, having always considered these multitudinous blogospheres a positive thing, albeit difficult to catalogue or classify, I think of the Ellen Ullman book I read a few weeks back, the essay about the internet as the opposite of democracy. Is saying, “Not my blogosphere,” I wonder, the equivalent of saying, “Not my blogosphere, not my problem?” Is relegating the entire internet to a serious of unconnected spheres—each one with a self-absorbed user at the middle—a sorry statement about the possibilities of online connection and the possibility for societal change in 2018?

I wonder. The internet is a blurry place. My friend, Dr. May Friedman, talked about this in her book, Mommyblogs and the Changing Face of Motherhood, when she wrote, “In trying to form conclusions about mommybloggers—and about mothers—I am reminded of my children attempting to jump upon their own shadows: I am attempting to trap an essentially untrappable form of knowledge.” In her book Friedman is more open to the amorphous nature of the blogosphere(s) than Duffy seems to be, open to the potential of the grey areas, to the possibilities represented by blogs being, as Duffy puts it, “murky conceptual spaces.” Although Friedman’s ideas about the radical potential of blogging were based on last decade in the blogosphere. We talked about this the other day and she suggested that perhaps the radical possibilities she’d written about had failed to become reality. So much so that Duffy’s understanding of the blog in 2018 as a hybrid space is devoid of radicalism altogether. Duffy writes, “Portmanteaus such as pro-sumption, produsage, pro-am, and playbour capture the nuanced ways in which production and consumption, work and play, and amateurism and professionalism bleed into one another in digital contexts.” Grossest hybridity ever.

In her book, Duffy is writing about our current moment, “…an era where the web’s non-commercial roots are largely forgotten, buried beneath a veritable heap of sponsored messages, native content, and cookie-tracked conversations.” Except that I haven’t forgotten those roots, roots that are blogging itself, I think. Roots I take my students to when I try to inspire them to write blogs and read blogs, real blogs instead of those pseudo-blogs that have hijacked an art form and turned it into a cheap commodity. #SoBlessed.

Realness and authenticity are indeed blogging’s roots, as Duffy writes, set in oppositional to magazines and advertisements, glossy and posed. Except that even realness been co-opted, underlined by market logic. To be authentic is to be “relatable”, but as a blogger becomes successful she becomes more difficult to relate to and her authenticity becomes a pose. Further, “…for many aspirants, individual expressions get refracted through considerations of audiences; one’s creative voice is synonymous with her commoditized brand…. Authenticity, thus, becomes a means to an end—namely drawing readers and potential advertisers.”

Which is why I tell students to “Blog like no one is reading.” Clever because, for most of us, often no one is. Those superstar bloggers who’ve been able to quit their day jobs and live off the fruits of their leisure/labour/soup are clearly exceptions to the rule. These bloggers have won what Duffy references, via Andrew Ross, as “the jackpot economy.” For the rest of us, we’re going to get paid a pittance, if anything, and this is Duffy’s complaint with the soup we’re being sold, “the dubious reward structures for aspirational labour.” The idea of a “partnership” between a huge corporation and a twenty-three year old woman with a Bachelors degree working out of her bedroom. How calling it a partnership makes it almost seem like fairness, which is another way the labour of blogging is rendered invisible.

And the labour is only intensified by the need to have it all seem so effortless. The work must necessarily be concealed. “I just happened to be doing a yoga pose halfway up a tree,” says the Instagrammer. Except: you had to climb the tree, someone had to take the photo, someone had to buy the camera, fix your dress so that your underwear wasn’t showing… “Their shots are often cannily staged to ensure a particular aesthetic—one that cloaks the staging itself.” And the statistics are likely that you’re never going to make it to the upper echelons, so what’s the point of all this work? (Me: If blogging is a lot of work, you’re doing it wrong. The point of the blog is to be raw, and unpolished. Immediate.)

Immediacy is the opposite of aspirational, which was what I kept telling myself as I read Duffy’s book about the problem of aspirational labour. Instead of aspiring, I urge the writers in my blogging classes to focus on the immediate. Blogging is about capturing a moment, writing right now. Which is why I don’t do scheduled posts. Which is why I take holidays a few times a year, weeks away from my blog, because it’s good to have a break and also because it reminds readers that there’s an actual human writing here. Which is the reason I’ve been able to maintain my blog for more than 17 years and not expire from burnout. We don’t use our blogs to get to some place better, but instead to be present in the current moment, a moment that becomes obsolete in thirty seconds. To try and fail to capture some of the atoms as they fall.

(Blogging is very much about failure. Imperfection. It’s a project that will never be finished. It’s about typos and weird formatting, and things that seemed like revelation a decade ago that these days make you want to die when you read it. So you don’t. Archives are only nice in theory. But even still, to wish to banish your archive [although you don’t] only means that you have grown, learned, and a blog is a document of that process. Your blog, like your life, is a work in progress.)

But am I an aspirational blogger? Have I been one? I wonder this. When I started blogging in 2000, I definitely wasn’t, because there was no template for blogs as a path to anywhere. I was just glad to have a place where I could write things, and people might read them. I had a voice. It seemed like a powerful thing, and not the opposite of democracy. Around 2004/2005, I was reading a lot of book bloggers, and aspiring to have a blog like that, I suppose—but that I aspired to have a blog like that is not the same as being an aspirational blogger. (Also, at the time I did not have a book blog.) By 2005 I was in graduate school, and did a project on “blooks” (whose title was, “Oh no! Not Another Portmanteau!”). So by this point, I knew that blogs could be a path to somewhere, but I don’t think I ever thought about being on that path. I was blogging for the same reason I’d been blogging since 2000, which was to make sense of things, for posterity, to ask questions. My blog turned into a book blog because my life had turned into a book life, and that’s the way it goes.

In 2007, a publisher offered to send me books. This was the first time I remember feeling vaguely aspirational. I felt legitimized, recognized, more than “just a blogger.” Was I selling out, I wondered? For about five minutes, but I said yes because I wanted books. And I thought about this too as I read Duffy’s book: are books “product”? Is me receiving books from publishers different from fashion bloggers receiving items for promotion? Maybe, maybe not. I’m thinking towards the latter because I don’t see it as my job to market books. I review a small fraction of the books I’m sent for review. I also obtain books by other means: I buy them, I borrow them from the library. And the people who read my reviews can borrow them from the library too. It’s not all necessarily driven by “market logic.” But when I was listening to Duffy speak, she gave the example of bloggers who make a big deal out of having purchased certain items—as though partaking in capitalism was a more legitimate way to appreciate something. And I do this too, I realize, making a big deal out of the books I buy “with my own money”.

Why I am I photographing my book hauls? Telling you about the bookshops I bought them at? Again, with books, I suppose it is different, and bookshops too—books are culture, the shops are cultural centres. There is an argument to be made that this is distinct from me writing a post about the new boots I bought at Nordstroms. Except that I do frequently write posts about buying things that aren’t books—I love photographing my brunch at cool restaurants I visit. I love tagging locals shops and designers when I’m wearing their clothes. When we got our new couch last month, I was all over Instagram because my couch had its own personal hashtag and I thought the brand was cool, and I was a bit cooler because of proximity. Social media had allowed me to feel connected to these brands, to feel like there was a relationship—which is kind of weird, and Duffy writes about the strangeness of your friends being brands, and brands being your friends.

That I am purchasing items and services from these brands underlines my authenticity though, or so it seems. (Even though I also want you to think I am cool because I have a mid-century modern sofa, for example.) Demands for “purity” means real (or “real”) bloggers don’t do it for the money or sponsorships. Getting paid is selling out. Although isn’t it only fair to want to be compensated for one’s labour? Should we necessarily denigrate someone for wanting to get paid for doing what they love? (Except, of course, one rarely does. One gets paid to write stupid posts about soup.) We turn down our noses at aspirational bloggers. Which means that everyone has to tell the same story about how they became a successful blogger but by accident.

So much of this is gendered. Women aren’t supposed to be aspiring. Also, the “partnering” and the promoting of brands they love is a gendered form of labour with a long history. Women are “social.” Do women face more struggle for trying to get fair compensation for their work? In general, yes. Is shitting on bloggers for “selling out” part of that same pattern? It’s more difficult for women bloggers, I think, because they must necessarily invest their personality in the work they do. (We make fun of self-branding, but also expect women bloggers to give of themselves.) And so the balance is harder, and the terribleness is obvious when the balance is lost—see the soup post, and the Happy Anniversary #Ad. “Authentic” and “real” are terms that get thrown around, but I think that most of us still turn to blogs for the human voice, which has been the appeal from the very start. And when the blogger is writing about things she doesn’t actually care about, the whole point of the endeavour is lost.

I don’t think that blogs can be successful commercial endeavours. There are a few exceptions to the rule—I can thing of a single blogger whose sponsored posts I ever read and shared—but in general, if you want to make money, you should do something that isn’t blogging. Which is why I insist that my students that they should get a pay-off from their blogs in other ways (that are not soup): my blog taught me to write book reviews, to engage deeper with the books I was reading. My blog was useful to me; it still is. And not just because I use it in lieu of possessing a short-term memory. These days I am challenging myself to write a post like a column once a week. I’m still learning from my blog, still growing because of it. My blog serves me, and not the other way around. (See my previous paragraph about blogs being raw and unpolished. About taking holidays). I get around the idea of blogs being unpaid labour by insisting that they shouldn’t take up that much of your time. A lot of professional writers, academics in particular, struggle with this, imagining that ever post demands hours of research, references. Or, I suppose, the labour I wrote about above with the woman doing yoga up the tree—and add to that obligations to promote that post via a lot of social media platforms. If you’re doing that much work and not getting paid for it, it’s not the blog’s fault, it’s your fault.

“But aspirational labour has succeeded in one important way; it has glamourized work just when it is becoming more labour intensive, individualized and precarious,” writes Duffy. I am older than a lot of her interview subjects. I have been blogging for almost half my life, and blogging fits into my life by now as easily as reading does, as breathing does. I am fortunate that my blog has delivered me to a writing career, even though I didn’t see it as a tool for that exactly. I mean, I always wanted to be a writer, and my blog was just a place to exercise, to practice. When I finished my Masters degree and failed to publish my novel, I saw my blog as consolation instead of a launching pad; a place to write that was mine, and where in my moment of failure I could still be creative. Creating. Another thing though: I have a husband with a full-time job and health benefits. If I didn’t have children I would be able to work more and earn more money; but if I didn’t have a husband with a full-time job and health benefits my lifestyle would be severely compromised. I’d be taking photos of fewer stylish desserts on Instagram, is what I’m saying.

But still, it’s easy for me to say that, “Blogging should be easy,” when I’ve got a brand, like it or not, and an audience, a platform. If I was young and just getting started, the rules I play by might no longer apply. Although I like to think that they do. Yes, if you play by them you’re unlikely to hit the professional jackpot, but blogs are inherently marginal and obscure. “Well-known blogger” is an oxymoron, remember? But if you blog by my rules you won’t get stuck doing yoga halfway up a tree. Self-expression won’t become linked to marketability. You will be blogging like no one’s reading, and figuring out what you really mean, learning what your voice sounds like, what you think, and what you have to say. And you might be aspiring, yes, but isn’t everybody? Aspiring to get to the next work, the next sentence. Everybody who writes anything is aspiring to be read.

January 29, 2018

Encyclopedia of An Ordinary Life

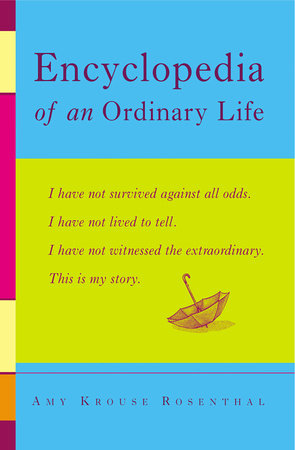

I got Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life out of the library on Friday and devoured it in two days while annoying everybody in my presence because I’d insist on reading passages aloud while they were trying to play Pokemon or read a different book or conduct a conversation. I loved this book so much, for all kinds of reasons, which weren’t necessarily the reasons its author intended the book to be loved when she published it for the first time in 2004. Except for this one: that she’d intended the book as a document of ordinary life at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and at this it succeeds so wildly, but so much so because life in 2004 seems very far away from 2018, where I read this book now. Answering machines, compact discs, and faxes. There is an image of a Yahoo email message, and I’d forgotten what those looked like—the font, the logo, the peculiar line breaks. The internet exists, but you’re not carrying it in your pocket, your purse. It’s still rife with possibilities for human connection, old friends getting in touch, hearing from strangers. The internet in 2004 was bringing us closer together instead of driving us further apart.

I got Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life out of the library on Friday and devoured it in two days while annoying everybody in my presence because I’d insist on reading passages aloud while they were trying to play Pokemon or read a different book or conduct a conversation. I loved this book so much, for all kinds of reasons, which weren’t necessarily the reasons its author intended the book to be loved when she published it for the first time in 2004. Except for this one: that she’d intended the book as a document of ordinary life at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and at this it succeeds so wildly, but so much so because life in 2004 seems very far away from 2018, where I read this book now. Answering machines, compact discs, and faxes. There is an image of a Yahoo email message, and I’d forgotten what those looked like—the font, the logo, the peculiar line breaks. The internet exists, but you’re not carrying it in your pocket, your purse. It’s still rife with possibilities for human connection, old friends getting in touch, hearing from strangers. The internet in 2004 was bringing us closer together instead of driving us further apart.

This book had absolutely nothing in common with Ellen Ullman’s Life in Code, which I finished reading a week ago, except that both had me thinking about the internet’s early days and all that possibility for connection. Rosenthal’s book reminded me of how exciting it was to be on the internet in 2004, the access to offered to worlds I didn’t know existed. The first job I had with an internet connection was at the Financial Post during the summer of 2001, which was the same summer I discovered that there was this fantastic literary culture happening in the world right now—that was the summer I bought White Teeth and A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. 2004 was when I was living in Japan and avidly reading Maud Newton and other book bloggers, and while actually becoming a book blogger still seemed like it was beyond me, living in a world where I had this window onto people doing and thinking and being literary culture was really astounding and transformative to me.

And Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s book gave me that same frisson of inspiration—these glimpses of fascinating people doing cool things. Or even mundane things, which this book is more about, the very point of it. The mundanity of the 2004 internet is also something I missed, as opposed to the YOU WON’T BELIEVE WHAT HAPPENED NEXT… clickbait. Smart people being boring, was the theme of the internet in 2004, or at least the corners of it I frequented. And it’s how I fell in love with blogging, really. The way that smart people being boring illuminated the secret wondrous corners of everyday existence, its various miracles the dancing dust motes (were dust motes actually things that people noticed who weren’t characters in novels).

She also writes a lot about death, which would not be so noticeable were she now, in 2018, not actually dead. It makes this ordinary book much more poignant, extraordinary, necessary, a gift. (See my 2015 post about blogs as “survival gear for our stories.”)

“I shopped for groceries. I stubbed my toe. I danced at a party in college and my dress spun around. I hugged my mother and my father and hoped they would never die. I pulled change from my pocket. I wrote my name with my finger on the cold fogged-up window. I used a dictionary. I had babies. I smelled someone barbecuing down the street. I cried to exhaustion. I got the hiccups. I grew breasts. I counted the tiles in my shower. I hoped something would happen. I had my blood pressure taken. I wrapped my leg around my husband’s leg in bed. I was rude when I shouldn’t have been. I watched the cellist’s bow go up and down, and adored the music he made. I picked at a scab. I wished I was older. I wished I was younger. I loved my children. I loved mayonnaise. I sucked my thumb. I chewed on a blade of grass.

I was here, you see. I was.”