January 5, 2026

What I Read on my Winter Vacation

Holiday break! This year I only read books by British lady writers whose pub dates span most of the 20th century. It was a pleasure!

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, by Muriel Spark: I’ve been reading a lot of Muriel Spark in the last while, and welcomed the opportunity to finally reread The Prime…, which I initially encountered in a first year university English class, and almost all of it went over my head. Muriel Spark’s work is strange, sly, and sneaky, and this slim volume is especially subtle. In all her work, there is also a religious element I don’t fully understand, so I’m always a bit unmoored when I’m reading her, but this time I was grateful to easily have a better understanding of the book. While it’s very much about girlhood, the novel’s scope is very broad and I think I personally had to be older to really understand it. It’s also funny, and brutally devastating in a vicious yet understated way that is easy to gloss over if one is not paying attention—I really wasn’t back then, or just didn’t have the right kind of antennae.

Offshore, by Penelope Fitzgerald: I have a complicated relationship with P. Fitzgerald, whose novels were off-putting upon my first encounters, and in some ways they continue to be so—I don’t read her as easily as I do other English writers. Her perspectives and framings are always just a little “off” from what I’m expecting, and there is a strangeness too that’s a little akin to Spark. But so many people I admire love her AND her books are short enough that they’re easy to reconsider, and so I’ve done so, and read them all, connecting with her through this challenge. I also connected via her wonderful biography, by Hermione Lee, which I loved—her own story is fascinating. Anyway, in December I read the novel Fonseca, by Jessica Francis Kane, a fictional telling of an experience Fitzgerald had in Mexico in 1952, and while I liked it, but didn’t love it (it was strange and a bit obscure in the same way I find Fitzgerald’s work, probably deliberately so), it did put me in the mood to reread some of her work, so I picked Offshore, set in the 1960s, about a motley crew of variously desperate people living on London canal boats—something Fitzgerald knew about, as she’d spent time raising her own children on a canal boat during some of many lean years, a situation which finally ended when the boat sunk and landed at the bottom of the Thames.

The Rector’s Wife, by Joanna Trollope: It was at this point that the themes of my winter reading became clearer—I was going to be reading about rectors, vicars, and curates well into the new year (and Bishops too!). Even Offshore had an interfering Priest, although he didn’t have a lot of impact. Also Joanna Trollope had died earlier in December, and so it was time to finally read this novel which I stole from a rental cottage the summer before last, drawn by its Pym appeal. It was very fun and rich, the story of a middle-aged woman who has delayed her own chances and dreams in order to serve her husband’s interest as a rector in a rural English community. But when he fails to get the promotion he’d been hoping for, she finally takes matters into her own hands, getting a job stocking shelves in a grocery store in order to finance their troubled youngest child’s private schooling—although it’s also more than that, setting off a cascade of events that change everything.

A Game of Hide and Seek, by Elizabeth Taylor: I don’t really have a sense of Elizabeth Taylor (the other one, who did not have violet eyes), but every time I read her, I’m surprised by her talent, and glad that I did. This one is about Harriet, the unremarkable daughter of a suffragette whose quiet life is disturbed when she falls in love with Vesey, the nephew of her mother’s friend, the flame he lights in her heart enduring even after the two are parted (they were barely together) and she finds respectability in marriage to an older man. Which means that when Vesey reappears in her life decades later, she can’t help but act on her feelings and the attraction between them, even at the risk of upsetting everything in her careful life. There’s a lot of humour in this one too (the shop where Harriet works where wages are so low that the employees feel justified spending their workdays taking care of personal needs, like doing their ironing, or waxing their upper lips). Richly textured, and full of such understated feeling, I enjoyed this one a lot.

A Few Green Leaves, by Barbara Pym: The Barbara Pym read odyssey continues, and I loved this one, her final novel, released posthumously. Pym’s novels are either set in London, or in rural villages, this one being the latter, in which a 30-something anthropologist moves into a cottage and becomes swept up in community affairs, and possibly an attraction to the widowed rector who is much occupied by local history. It’s very much about the passage of time, and there are mentions of characters from Pym’s previous novels—the formidable Esther Clovis, in particular—having died. I think this would be a weird, albeit still enjoyable, novel to pick up and start reading out of the blue, but in the context of Pym’s oeuvre, it’s very poignant and lovely.

The Little Girls, by Elizabeth Bowen: Bowen is another writer I sometimes struggle with. I’ve really enjoyed some of her novels, but found others really hard-going, almost as though they were a deliberate running of circles around their points. This one was also a little bit hard to understand, and very odd—it was her second-last novel and perhaps not wholly representative of her body of work. It was fiercely funny in places—an eccentric widow places ads in all national newspapers in order to locate two old friends with whom she’d partaken in a pact during their school days just before WW1, but also there are parts where I’m still not sure what actually happened, the story so thoroughly obfuscated, a little too much going on. It was not my favourite

The Knox Brothers, by Penelope Fitzgerald: The one book in this stack that’s not a novel, but it’s by a novelist, so it counts? I happened upon this secondhand copy of Fitzgerald’s biography of her father and uncles, and wasn’t quite sure how much I’d be interested in these men’s stories, but it turned out to be A LOT. The Knox brothers were the sons of the Bishop of Manchester and the daughter of the Bishop of Lahore, four out of six children, and were remarkable every one. The one who grew to be Penelope Fitzgerald’s father became the editor of Punch Magazine, another was a famous cryptologist in both world wars, the other two both were priests, one of whom ended up converting to Catholicism (and FINALLY this book gave me the context for the Anglo-Catholic questions that come up again and again in Barbara Pym novels where priests are continually “going over to Rome” or being suspected as such). Even more remarkable than their accomplishments and eccentricities, Fitzgerald underlines how her father and his brothers were kind and loving men, feeling people in a time where men of their class were not commonly thought to have such emotional capacity. I loved this one.

Family and Friends, by Anita Brookner: And I loved this one too, though I was wary. Some of Brookner’s novels are incredible dense, opaque, and more cerebral than anything else, but this one (which followed her Booker-winning Hotel Du Lac in 1984) seems to be the exception to the rule. Not cerebral in the slightest, it begins with a family photograph and glosses across the surface of that family’s history across decades as things are ever-changing and nothing ever quite unfolding as expected. Fast, sweeping, and engaging, this turns into a remarkable portrait of seemingly ordinary people, highlighting the less flattering aspects of its characters. Playful and surprising, this one as a pleasure.

Whose Body, by Dorothy L. Sayers: I wasn’t planning on reading Sayers, except then I watched Wake Up, Dead Man, the new “Knives Out” movie, and this novel is referenced (and also Penelope Fitzgerald’s priest uncle Ronnie Knox was also a detective novelist and contemporary of Sayers—they were both members of The Detection Club, along with Agatha Christie, and others). I came to Sayers and Peter Wimsey via Harriet Vane, and was sort of uninterested in reading any of Sayers books in which Vane doesn’t feature (which was most of them) but getting to know Wimsey and his vulnerabilities (he’s suffering from shell shock in the early ’20s; his mother admits it might be too much to ask someone to get over a war in just a year or two) was fascinating. The mystery was satisfying and not too convoluted, although the antisemitism was unpalatable, though at least it was mostly displayed by the novels villains, but still.

The Life of Violet, by Virginia Woolf: This little book is a collection of three short stories written by Woolf when she was still Virginia Stephen, back in 1908. This work had previously been regarded as unimportant, but then a polished draft was discovered, resulting in this publication of these three fables inspired by the life of Woolf’s friend Violet Dickinson. Dreamy, funny, and whimsical, the stories are also remarkable for how they feature elements that would continue to preoccupy Woolf’s creative work—biography, rooms of one’s own, the lives of women—for the rest of her career.

An Unsuitable Attachment, by Barbara Pym: My Pym reread is nearly complete! This was an earlier Pym novel that remained unpublished until after her death, and lacks the (even unplumbed) depth of her later work, but is still very charming, and it was kind of amazing to read back into the past in order to see Esther Clovis resurrected!! This is one of Pym’s urban London parish books, complete with a sojourn to Rome. There is a librarian, a pampered cat, a lugubrious vicar’s wife, chicken in aspic, an anthropologist, and a bedraggled beatnik—what more could a reader want?

Pack of Cards, by Penelope Lively: And I am so THRILLED to be loving this book as much I am, because it’s a pretty big commitment—more than 30 stories by Penelope Lively published in one volume in North America after her Booker win for Moon Tiger in 1987. (It includes the contents of her first two story collections and nine new stories). Fortunately, the stories are wonderful, and I’m gobbling them up—I’m nearly two thirds through now. I don’t think I’ve ever read her short fiction before, but it’s just reminded of what a wonderful writer she is, and now I want to reread the huge stack of her novels that I own, most of which I’ve not read in years.

November 10, 2025

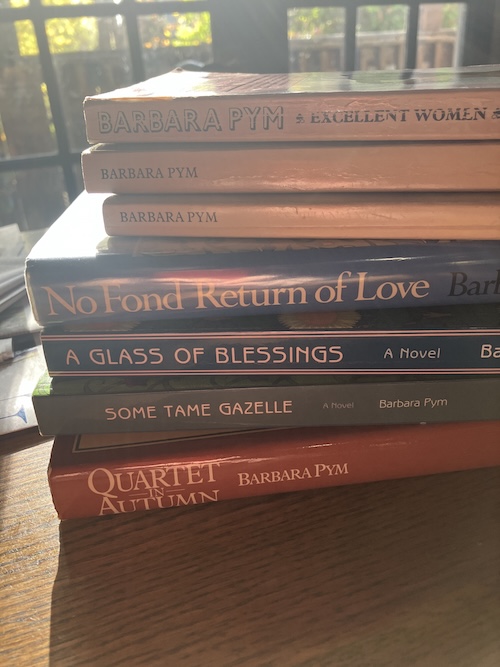

A Stack of Pym

Did you know my forthcoming novel, DEFINITELY THRIVING, began with my intention to write a Barbara Pym story, but in a contemporary setting? Which means that my book indeed features a tea brewed with water boiled on a hot plate, church committees, considerations about what it means to be an unmarried woman without children, unsuitable attachments, some questions of indexing, a jumble sale, and many more wondrous things, including a protagonist with a name like Clemence Lathbury.

Rereading all of Barbara Pym has been one of my many 2025 reading projects, one I’m not going to complete before the year is out, but luckily most reading projects don’t have a deadline, and I’d actually be disappointed if I were finished. I’ve finally read up to Quartet in Autumn, her first novel published after 16 years in the literary wilderness and her discovery via recommendations of her by Phillip Larkin and David Cecil as one of the most underrated authors of the 20th century. I’ve never read her in sequence before and it’s interesting to consider what a different book this is than those that came before it—but the continuities as well, the things that make a novel a Barbara Pym novel (nosy people looking up clergymen in Crockford Clerical Directory for certain, a forerunner of Google!) and all the complexity that lies beneath these books’ deceptively simple surfaces.

June 2, 2025

Happy Birthday, Barbara Pym

It was 12 years ago today that I baked a Victoria sponge cake in honour of Barbara Pym’s centenary, and also because I was almost 42 weeks pregnant and had time on my hands. I went into labour shortly thereafter, which would have made for a better story had my labour not subsequently stalled with my baby born three days later by c-section instead of the home birth we’d planned with a shared birthday with the extraordinary Miss Pym. But Pym having a day of her own is most fitting, in retrospect, and I’m rereading all her novels this year just to be reminded of this (before my own Barbara Pym-inspired novel is published early next year!). This weekend I reread Jane & Prudence, her third novel, which received mixed reviews upon publication in 1953, and as I was reading the first two thirds, I was all set to explain how this was a second-rate Pym novel (her characters are a little too silly, it’s a reworking of a novel she’d written in the 1930s and perhaps less fresh for that, the set-up is artificial) but then at some point the novel won over entirely and I loved it as much as I loved everything Pym wrote. It’s an Emma-aware story of matchmaking gone awry, so-called matchmaker in question Jane, an unconventional vicar’s wife (she’s got an Oxford degree and no affinity for domestic tasks), who tries to arrange a relationship between her former student, 29-year-old Prudence, and her new neighbour in the village she and her husband have just moved to, the perhaps dastardly widower Fabian Driver. But then fate has other plans. Jane & Prudence is not the place to start with Pym, but the novel is not to be missed either.

May 28, 2021

Pfingsten

I’ve been reading Barbara Pym all spring, as I’ve mentioned several hundred times, and the Anglican rituals, for me, have always been the most curious aspect of these books—the vicars, and the curates, and the cassocks. What’s a cassock? I don’t even know. And especially: what is Whitsun? Whitsun, which is never a major plot point, but simply part of the course of the year (and occasion for a bank holiday). I had to google it—Whitsun is the Pentecost (and then I had to google that, and I still don’t really get it), celebrated the seventh Sunday after Easter. And frankly, not a lot—Barbara Pym aside—has been going on this spring, as Ontario moves into its eleventeenth month of lockdown, so I decided this was the year I was going to make Whitsun a thing. What that would entail exactly, I wasn’t sure. Definitely not church. But we needed something to look forward to, a goal to shoot for, and so Whitsun it is. (And indeed, this is cultural appropriation. Church of England Cultural Appropriation. It’s not the same thing.)

I decided this during a terrible weekend in mid-April where our provincial government’s incompetence took a swan dive off a cliff. Finally, after the government waiting to see whether modelling numbers predicting ICUs being overwhelmed with patients would play out in reality (SPOILER: they did! Who would have guessed?) the province moved into a locked-downier lockdown from the lockdown we’ve been locked down in since November 23. Six weeks on from then would be Whitsun. Surely by Whitsun, I told myself, we would find ourselves in a better place? Keep looking in the direction of the place you want to get to has been my motto all along…

And here we are, with falling infection rates, with vaccine rates that are really high. We were still in lockdown for Whitsun and the lockdown carries on, but it was so good to mark a milestone on a weekend with such beautiful summer weather. I’d also ordered peonies, because I’d received an enticing ad from a local florist, and the great thing about made-up holidays (all holidays are made-up holidays, even Whitsun, though I’ll acknowledge that my version of Whitsun was particularly improvised) was that you get to make them whatever you want. Whitsun peonies, I decided. And we’d make a Victoria sponge cake. I booked a car so we could go somewhere. We were going to make this the best Whitsun ever!

And it was! It was already a holiday weekend in Ontario and we’d gone for an epic bike ride the day before (Whitsun Eve). On Whitsun itself, we had Sunday waffles as usual but they just tasted better for it being Whitsun. I finished the book I was reading (Day for Night, by Jean McNeil, which I’ll be writing about here soon…). We went to Ontario Place, and had a second weekend in a row with two lake days in a row. We got ice cream. We came home (no traffic) and had an amazing barbecue supper, and then just as I was assembling the Victoria sponge cake (which was beautiful and delicious and did not look like it had been assembled by a blindfolded toddler—a first for me!) a friend sent me a text and asked if our family would like to join theirs for fireworks in the park that evening.

I can’t believe they were lighting fireworks for Whitsun!

Our children have never seen fireworks before and it turned out to be the most magical display, the first real life communal experience we’ve had while not sitting in a vehicle since March 2020 (albeit at safe distance for other people and also explosives). It occurred to me that if everybody just carried around lit sparklers all the time, we’d have no trouble staying six feet apart at all.

Even more cool things: on Sunday I was scrolling through the #Whitsun hashtag on Instagram, and what do I find. Peonies! Whitsun peonies EVERYWHERE. It turns out that the Pentecost is a national holiday in Germany and peonies (pfingstrose, translation Whitsun Rose) are the official symbol. Sometimes when you’re making it up you get it exactly right.

Not all days are glorious. Our bike ride on the Saturday before Whitsun was hot and full of whining. When we finally got to our destination, the beach was full of thick green algae and bugs were swarming us. A very loud church service was being amplified unavoidably, and it was weird and obnoxious. I was allergic to something and broke out in a rash, and on the long ride home we got caught in a rainstorm. “That was awesome,” we said at the end of the journey (20km) but also absolutely awful.

Whitsun though. Whitsun was perfect. Sometimes you get lucky. Sometimes you get to make it up and everything goes right.

May 13, 2021

The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, by Paula Byrne

I…don’t like big books. They’re heavy to hold, don’t fit in my purse, and I’ve just got no time for that, for the most part. It just doesn’t groove with the pace of my life, and so at 612 pages, I was intimidated by The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, Paula Byrne’s biography of novelist, the first since a 1990 biography by Pym’s friend and literary executor Hazel Holt which might have revealed fewer insights that it could have out of respect for Pym herself, who’d died of cancer in 1980.

But reader, I read it in two days. Granted, these were two days I’d set aside especially for it, turning off my wifi and accompanying social media so all my attention could be focussed on the task at hand, which was giving my poor wrists the support they needed to hold Byrne’s biography up to my eyes. But it helped that Byrne had divided her book into short and action-packed chapters in the style of 18th century novels like Moll Flanders, chapters with titles such as “In which our Heroine is born in Oswestry,” “In which Miss Pym returns to Oxford,” and so on to “In which our Heroine goes to Germany for the third time and sleeps with her Nazi.”

TURN BACK, BARBARA! was what the residents of my household took to shouting as I kept them abreast of developments in the narrative, such as when Barbara was having an affair with her friend’s father, various gay men, her roommate’s estranged husband, and yes, a literal Nazi. Barbara Pym was an extraordinary person, a brilliant novelist, and had comically terrible judgment when it came to men (and 1930s’ political regimes). Although it occurs to me that her terrible judgment may have been what made her such a wonderful novelist, her ability to imagine her characters into the impossible situations she’d often encountered herself. She took the tragedies (and absurdities) of her own life and spun them into literary (and comic) gold.

Barbara Pym was a fascinating woman—a student at Oxford in the 1930s, she was an enthusiastic participant in sexual relationships, and imagined herself into all kinds of romantic dramas, her particular obsession with one lover occupying her for the rest of her life. She was very drawn to Germany in the 1930s, displaying that typical judgment I’ve always mentioned, but this did not persist into wartime, where she would serve with the WRENs in Naples. After the war, she was hired as an editor for an academic journal in anthropology, which served as fodder for her work (oh my gosh, her treatment of office dynamics and whose job it is to put the kettle on and how is SO SPOT ON) but also paid her a pittance. Being a novelist was most fundamental to her identity out of everything else she did—her first novel, Some Tame Gazelle, was published in 1950. She’d been working on the novel since her Oxford days.

Throughout the 1950s, she published five books, her sixth appearing in 1961. And after this, her new work was not accepted by her publisher, nor by any another. The fashions were changing, and so was the publishing industry (everyone thought the industry was just as dire then as they have ever since), and Pym’s understated humour and wry old-fashioned sensibility had not kept up to date, it was said. So she would toil in the wilderness, encouraged by her excellent friend Philip Larkin, and these years were hard ones for her—money was a struggle, she was depressed by romantic relationships that didn’t pan out, she encountered health struggles, and felt left behind by the literary scene.

And then everything turned around—in 1977, Pym was mentioned (twice!) in a Times Literary Supplement list of underrated writers. All of a sudden, the newspapers and radio were calling. Her publisher wanted to put her back into print, she relished in rejecting them this time, new works coming out with MacMillan, her earlier books re-released. Her next novel, Quartet in Autumn, was nominated for the Booker Prize. Pym would be celebrated before her death at the age of 66, which gives this life the happy ending her biography’s reader longs for. The kind of triumph that doesn’t always happen in life itself, and seems more fitting for a novel instead (but then we’d call the conclusion a little bit pat).

Byrne refreshes one’s perception of Pym in this biography, whose title and form is entirely suited to a life that wasn’t quiet at all, and which pushed the margins in all kinds of ways. She also shows the way that Pym’s work was a reflection of its times, and changed along with the fashions, responding to the world around her, even though many of her preoccupations (spinsters and curates especially) remained the same.

April 23, 2021

Jane and Prudence

I didn’t plan on Spring 2021 being Barbara Pym Season, but the most interesting parts of my literary life have always happened by accident. It all began when the Barbara Pym Society Spring conference once again went virtual, which meant that I had the means to attend, and so I picked up An Unsuitable Attachment in preparation, and this, along with the release of Paula Byrne’s Pym bio this spring AND my voyage into writing an Pym-inspired novel, made me decide to reread her all her books. (As I wrote in my essay on comfort reading last month, they’ve always tended to blend together in my mind…) And so after An Unsuitable Attachment was finished, I read Excellent Women again, which for some reason I thought was her first book, though maybe it was because it was my first Barbara Pym. And then I decidedly to read in actual chronological order after that, beginning with her real first book, Some Tame Gazelle, which I enjoyed well enough but it lacks the depth and political bent of the rest. Pym began writing it as a student at Oxford, clearly having fun imagining the lives of the 50-something spinsters who would come to be her chief subject, but she wasn’t as good at it then—neither at writing novels nor grasping the brilliant multitudinousness of ordinary experience.

By Excellent Women she’s figuring it out, but how Jane and Prudence she’s on fire. Little plotwise actually happening in either book, but it’s about the nuances—the fit of a dress, the cut of a comment, what these things signify, and often so much is about the inferior status of women in society. Jane Cleveland sitting down to a meal in a restaurant with her husband, and noticing that he’s served more food than she is. “‘Oh, a man needs his eggs!’ said Mrs. Crampton… This insistence on a man’s needs amused Jane. Men needed meat and eggs—well, yes, that might be allowed; but surely not more than women did?”

I love so much about this very strange novel—first, that at its heart it’s about friendship (though I will admit the plot is a bit thin on what draws the two women together. We don’t really see their chemistry, but I don’t think is the point) between two women, women who are some years apart in age, and also one is married while the other isn’t. The women not serving as foils to each other either—neither marriage nor singledom is the answer to the question of how get the meat and eggs one requires for a satisfying life. Both situations bring with them complexities and quandaries. The realities of 1950s’ austerity apparent too—it’s a crisis in Prudence’s office because they’ve already finished their tea ration! (In Excellent Women, Mildred Lathbury attends church in a building that’s only half functional, because the other aisle was destroyed in a bombing…)

Jane and Prudence is actually quite a subversive novel. There is infidelity, inappropriate love affairs, the clergyman’s wife is ill-suited to the role but firmly herself all the same—her talents don’t lie in domestic sphere, and she’s fine with that. Both Jane and Prudence are unapologetic in all the best ways, and like all the best books about women, nobody has to change. The eligible widower too ends up with the the most unlikely prospect, and that the mousy Jessie Morrow finagled all that herself—I love it. And the wisdom too: “But of course, she remembered, that was why women were so wonderful; it was their love and imagination that transformed [men—] these unremarkable beings. ”

October 17, 2017

A far cry from Mr. Stillingfleet’s stuff

I’ve never been to the Victoria College Book Sale on opening day before, because it’s always on a Thursday and you have to pay $5 to get in, but I hadn’t planned my life well during the weekend the sale was happening last month, and my only chance to go at all would be during the ninety minutes between when the sale kicked off at 2pm and when I had to pick my children up from school at 3:30. So I cobbled together the admission fee, literally out of dimes and nickels from a jar in my kitchen, which made for very heavy pockets, but I got there, and learned of just one distinction between the Victoria College Book Sale on its first day and all the days thereafter: there are Barbara Pym books for sale.

It’s difficult to find used copies of Barbara Pym novels. Her readership was never huge enough, at least not in Canada, as compared to writers like Margaret Drabble, Hilary Mantel and Penelope Lively, whose novels are mainstays at secondhand bookstores (which is the way that I fell in love with all of these writers, and others). I like to think, however, that it’s not just that Pym’s readers are few and far between, but that they’re also quite devoted. The secondhand copies of Barbara Pym novels that I do have came from a house contents sale in my neighbourhood after the death of its elderly owner (which in itself is kind of Pymmish), and that’s the only way I’ll ever be getting rid of Barbara Pym books, by which I mean: over my head body. (I imagine they’re easier to find in secondhand bookshops in England; also, many of her works have brought back into print by Virago Modern Classics with fun cartoonish covers in the last ten years and I’m sure those copies are turning up in charity shops).

Anyway, finding Barbara Pym novels at the Vic Book Sale was exciting enough, but even more remarkable was finding one I hadn’t read yet. I thought I’d read them all, including a collection of her letters and another of unpublished short fiction, and the first book she ever wrote, Crampton Hodnet, which wasn’t published until after her death. I thought I’d spanned the entirety of the Pymosphere, and was content to spend the rest of my life then just rereading her, at least once a summer and maybe even more so, but then there was An Academic Question. I’d missed it altogether. Also published after her death, written during her wilderness years in the early 1970s (before she was “rediscovered” and brought back into print, winning the Booker Prize in 1977 and publishing two more books before her death in 1980).

I started reading An Academic Question on Friday night because I’d been reading A Few Green Leaves (the official newsletter of the Barbara Pym Society) in the bathroom (as you do) and then checked my email to find a reminder that I hadn’t yet renewed my Pym Society membership for 2017. I did so, and took note of the universe conspiring to send me in a Barbara Pym direction, and I’ve already got a backlog of books I have to write about anyway so this would be an excellent opportunity to read for fun and not have to write about it at all.

Take note: I am writing about it. Barbara Pym never fails to incite…

The novel starts off a little roughly. In her note on the text, Hazel Holt writes that it’s cobbled together from two drafts, one in first person and the other in third. Before the book’s spell had taken hold, I kept getting caught on clunky prose and repeated words..but then at some point these problems ceased or else I stopped noticing them. As per Holt’s note, Pym wrote to Philip Larkin of the novel in June 1971: “It was supposed to be a sort of Margaret Drabble effort but of course it hasn’t turned out like that at all.” Which interested me—I remember reading about Pym’s relationship to Drabble’s work in the years when Pym herself wasn’t being published, deemed irrelevant while Drabble herself was very fashionable, her antithesis.

You can see what Pym was up to here—this is a story of a young faculty wife whose sister has had an abortion and lives in London with a man who designs the sets for the news program her husband’s colleagues appear on, all the while the students at the university are going through a period of unrest. In a superficial way, this is Drabble’s milieu—but Pym can’t help but spin it in her own way. It’s the interiority of her protagonist, her doubts and questions, her sense of humour. Caroline is undeniably Pymmish in her preoccupations, spending most of her time with her gay best friend Coco who dotes on his high maintenance mother. While Drabble’s characters are all on the verge of slitting their wrists in a bathtub, Caroline is unfailingly stoic, even at a remove:

‘What was the point of it all?’ Kitty had asked me plaintively, and I felt that for her the evening had been a disappointment, as indeed so many evenings must be now. And what had been the point, really? A few gentle cultured people trying to stand up against the tide of mediocrity that was threatening to swamp them? I who had hardly known anything different could sympathize with their views but for myself I didn’t really listen to the radio; I went about my household tasks, such as they were, absorbed by my own broody thoughts.

And while this is one of Pym’s rare novels that doesn’t contain a single curate, let alone a mention of The Church Times, has only handful of references to jumble sales and the characters drink coffee instead of tea (I KNOW!), the humour is still wryly, undeniably Pymmish. The following passage would never be found in a Margaret Drabble novel:

We sat drinking cups of instant coffee and smoking, commiserating with each other. An unfaithful husband and a dead hedgehog—sorrows not to be compared, you might say, on a different plane altogether. Yet there was hope that Alan would turn to me again while the hedgehog could never come back.

The book wouldn’t work, Pym felt, according to Holt, for its cosiness, and it was remarkable how often the word “cosy” appears in the text (alone with the word “detached”). Which got me thinking about the literary implications of cosiness, as opposed to grittiness, I suppose. Thinking of cosy made me think of rooms, of comfortable sofas, piles of books on the table, interesting items on the mantel—all of which are things that furnish Pym’s books, including this one. Cosy isn’t fashionable, it’s true, what what it is instead is timeless, which might be why we’re reading Pym today while Margaret Drabble’s early novels seem so dated and are out print.

Pym’s Caroline is detached from her life as faculty wife—her husband has proved to be less interesting that she thought he might be, he’s been unfaithful, and she finds herself at a loss as to how support him in his work as one expects she should. She finds motherhood a bit boring and her daughter is cared for by the Swedish au pair anyway. Apart from her friendship with Coco, Caroline doesn’t have anyone to have real conversations with, and when she does talk to Coco, he has no qualms about finding her provincial life kind of tiresome. She spends some time reading to Mr. Stillingfleet, a retired professor at an old people’s home, revealing to her husband that the professor keeps a box of academic papers by his bedside…which ignites her husband’s interest in visiting the frail old man, so he can scoop material from the box and pull an academic coup over his superior. And then Caroline is left with the ethical question of what to do with the stolen paper afterwards, and just where her loyalties lie, and what compromises indeed she is willing to make in the name of her husband’s success…

“‘Hospital romances,’ I said to Dolly that evening when she called around to see us. ‘That’s what I’m reading now. It’s a far cry from Mr. Stillingfleet’s stuff.”

‘Maybe, but it is all life,’ said Dolly in her firmest tone, ‘and no aspect of life is to be despised.”

June 20, 2017

On the Bearability of Lightness

A couple of weeks ago, after a string of one-after-the-other satisfying spring reads, I couldn’t get into a single book. A problem that stretched out for a week, until I had no choice but to turn to a surefire solution, which was to reread a Laurie Colwin novel followed by one by Barbara Pym. The Laurie Colwin idea occurring to me because I’d created a job for a character in the novel I’m writing that seemed Colwin-esque—she was hired as a researcher at an institute for folklore and fairy tales. Which never happens to anyone in real life, but which is all the more fun to imagine for it. In the Colwin novel I read, Happy All The Time, not a single character is in possession of a real job. The book is about two friends, one whose job is to manage the philanthropic foundation that donates his family’s wealth and the other has a background in urban studies and works for a city-planning think-tank, where he meets his future wife who is a linguist working on a language project. The first character’s wife is just wealthy and doesn’t have to work, and spends her day-to-day life watering spider plants in her apartment, making soup, and rearranging jars of pretty things on her windowsills.

Do I sound critical of these details? I don’t mean to. It’s part of the reason I life Laurie Colwin, the rarefied experiences of a certain class of people but she gets at their ordinariness. It is all very strange, and an aspect of appreciating Colwin, I think, is learning to take that strangeness for granted. Which is not to say her books are frivolous, although they are in a way. But I think maybe the problem is that we have no template except for frivolity to understand a book that possesses a light touch. This is a novel that turns gender norms upside down, Jane Austen with the shoes on other feets. The two men at the book’s centre are yearning and emotionally complicated, besotted with emotionally distant women who don’t seem the appeal of love in all its frippery. There’s a lot of fascinating stuff going on here, although it’s easy to breeze right by it, to let it go down easy. It’s easy to give this kind of literature absolutely no credit at all.

What if instead of axes to the frozen seas within us, books were umbrellas to protect us from the ice pellets overhead? Or a house that we could go inside in order to escape from the weather for a while.

I read Barbara Pym after that, because I love her, but my confession is this: apart from Excellent Women (which is so so excellent, but they all are) I have a hard time remembering what Barbara Pym novel is which and they all run together. Which is why I try to reread at least one annually, and this time it was No Fond Return of Love, which I last read in 2010 (which I know because I then recorded a youtube video about how much I loved it). As with the Colwin, this is a book that skews with conventional narrative and is more subversive than it ever gets credit for. Really, it’s a story about stories, about seeing and watching and it’s an experiment in a novel with a protagonist who is not a protagonist at all. Very little of Dulcie’s story is her own, and she doesn’t even want it to be. She is content in her experience, but it’s other people’s experiences that fascinates her, and we keep waiting for the conventional things to happen, but they don’t. Dulcie is far more interested in other people than she is in herself, and so is the novel, which is pretty unusual. I think I read this one around the same time I saw the Emma Thompson film Stranger Than Fiction and read the Muriel Spark novel The Comforters which is similar, and so the metafictional elements of this Barbara Pym book (and the ways in which Pym represents her work and makes a cameo appearance) are underlined to me. I can’t remember if other Pym books are quite as self-referential as this one, or if No Fond Return of Love is an outlier.

In this novel too, things are arranged in jars on windowsills and we’re told what these things are and how the light things through them, and I think of the materiality of both Colwin and Pym’s work, how the furniture is so important. And is there anything wrong with books that are more concerned with end-tables than axes? What if literature didn’t have to be a weapon?

I read Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk next, which I read first in January, but I wanted to read again before my book club discussed it. A book I was so glad to get a chance to return to because it reads so easily you might almost forget it, or at least imagine there is not so much to remember. This the trouble with lightness, of course, is its deceptiveness. Which is the entire point of Lillian Boxfish, actually, and we had such a fascinating discussion about this book, about style and substance, about the way in which its narrator cultivates her persona and how reliable is she, is she writing us another rhyme? This novel written by a poet is written with such an awareness of language, and sense of play about it, and Lillian Boxfish’s point about her heyday is that there could be an intelligence to lightness then, humour and grace. And it made me think about Colwin and Pym, writers whose lightness might be held against them, as Lillian’s work is against her later in her life, dismissed as silly rhymes. But is there a difference between these silly rhymes and today’s silly rhymes, and has a basic assumption of a reader’s intelligence and vocabulary and capacity for challenge changed in the years since Pym and Colwin were published. Remember too that for many years Pym wasn’t even published, out of print for nearly two decades until her resurrection in 1977—so maybe it’s the same as it ever was?

I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, but I’m glad that reading light this last little while has given me so much to think about. Thinking about those pretty things in the their jars on the windowsill and the narrow space between light, light (illumination) and delight, which has no etymological connection, but it probably should.

December 21, 2015

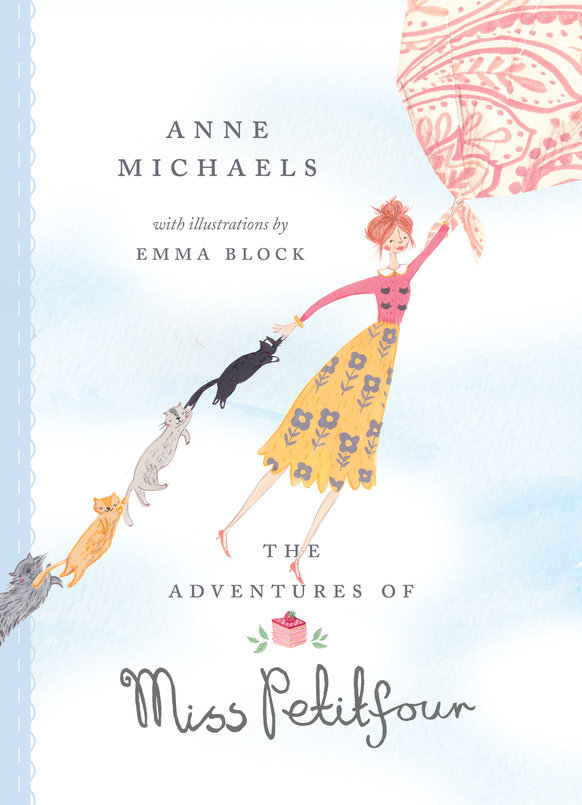

The Adventures of Miss Petitfour, by Anne Michaels, illustrated by Emma Block

While The Adventures of Miss Petitfour is indeed world-renowned writer Anne Michaels’ first book for children, it might be as accurate to state that it was written exactly for me. Bizarrely so. Right down to the bunting and teapot and caked goods on the endpapers. There is a jumble sale in the second chapter, for heaven’s sake, and every adventures ends with a tea party. There is an entire chapter about cheddar cheese. This was the other book that I bought last week, and we spent every night reading it together, being positively delighted. (Please do read this post by Lisa Martin, inspired by Doris Lessing, on the necessity of the capacity for delight as a precondition for resilience.) If a Barbara Pym novel married Mary Poppins, this book would be their progeny.

“Some adventures are so small, you hardly know they’ve happened… Other adventures are big and last so long, you might forget they are adventures at all—like growing up. And some adventures are just the right size—fitting into a single, magical day. And these are the sorts of adventures Miss Petitfour had.”

Miss Petitfour travels by table cloth, which is a terrific twist on the magic carpet, and much more scientifically plausible. She holds the table cloth just so and lets it fill with wind, and then up she goes (after she has taken “a measure of the meteorological circumstances, that is to say, the weather”), her sixteen cats trailing along for the journey. And their adventures are rich with digressions, narrative and actual, as well as bookishness, confetti, misdirections and festoonery. Charged with whimsy and fun, there is an underlying intelligence to these stories, which are so very much about words:

“People often say that children have no use for long words, but frankly, Mrs. Collarwaller [the bookseller] found this never to be the case. In her vast experience, children loved books that contained words such as propitious, perambulator and gesticulate, especially if they all ended up in the same sentence. The kind of word your tongue could get tangled up and lost in.”

In Miss Petitfour’s local bookshop, there are two sections: one side for adventure books and the other for books in which nothing happens (“the hum and the ho-hum”). In the most perfect way (in addition to the story about cheddar, there’s one about a runaway postage stamp, for example), this books manages to be both.

June 2, 2013

Victoria Sponge for Barbara Pym

I successfully baked a Victoria Sponge cake in honour of the Barbara Pym centenary (and because I feel like eating one). Recipe from Nigella’s How to Be a Domestic Goddess, with fresh Ontario strawberries inside. Here’s hoping it tastes as good as it looks. And happy birthday, Miss Pym!

I successfully baked a Victoria Sponge cake in honour of the Barbara Pym centenary (and because I feel like eating one). Recipe from Nigella’s How to Be a Domestic Goddess, with fresh Ontario strawberries inside. Here’s hoping it tastes as good as it looks. And happy birthday, Miss Pym!