April 27, 2022

The Direction of Your Dreams

I was recently writing in a journal of prompts in response to the question of what I’d like to tell my younger self about my life right now. And what I remembered was how much possibility my younger self once found in the phrase attributed to Thoreau , “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams and live the life you imagine.” Inscribing it into all kinds of scrapbooks, perhaps purchasing a poster of a sunset with it quoted.

What I’d tell my younger self: “Look! I did it.”

*

Two years after my first novel came out, I’d found myself in a creative jam. My publisher had rejected my next novel. I was proud of Mitzi Bytes, but its sales hadn’t set the world on fire, and I was feeling pretty despondent. Like this was my chance, and I’d blown it.

(Never mind that so much of things like book sales are outside an author’s control. Suspicions I’d long held were underlined in a really smart and candid recent post by novelist S.K. Ali, who wrote, “Your book sales are not yours to bear…if you love marketing, great! but a publisher has the greatest pull of all and can put a book on any list — NYT, Indie, USA Today etc — without you moving a finger. So, Sajidah, keep doing all of that stuff you do, giveaways, tiktoks, AMAs, but only because you love your readers. [Those things don’t move book sales. YOU don’t move book sales. Don’t bear that burden.]”)

It was late 2018, in response to that despondency, and feeling like I’d used up all my chances, that I decided to conjure some more. In 2019, I launched the #BacktotheBlog Movement, which led to Blog School, and also a wonderful bookselling project I’m still so proud of, the now-departed Briny Books. And then, in the midst of that summer, I signed a deal for my second novel, everything coming up Kerry after all.

*

I wonder if any advice I have to impart about going in the direction of one’s dreams would be as relevant if I hadn’t ended up defying the odds and getting that book deal in the end? I think it probably would, because my happy ending was not the end, but just another chapter (hurrah!), but experience has shown me that an author is never set, never really arrives, that writing, like everything, is a process of becoming, and the next thing is never sure. That the advice about going in the direction of one’s dreams never stops being applicable.

*

When I say, “Keep going! Don’t give up,” I’m not saying that you should keep beating your head against a brick wall. Sometimes “keep going” means doing something different, a shift, a pivot. I finished a novel in 2007 that nobody wanted to publish, and I’m glad I didn’t go to the ends of the earth in an attempt to find a publisher, because I might have found one if I’d tried hard enough, and that novel wasn’t very good.

What I’m saying is don’t stop creating things. Don’t stop being inspired. The wonderful thing about literature is that readers are so central to the form—there’s nothing passive about it. Keep reading. Keep engaging with ideas. Keep a notebook. Keep a blog. Maybe you have bigger dreams of projects you’d like to get to the end of, but in the meantime, a notebook, a blog. A quilt. A cake. A conversation. All these things are tangible and real. In keeping with the life you’ve imagined.

*

*

I started thinking about all of this in response to a recent post by Kelly Duran, whose kindness, generosity and candour as an author has been so refreshing to encounter. Her feelings about where she is two years out from her debut novel resonated with me for sure, and made think about the metrics we have to measure success. As well as the dangers on fixating where we’re going instead of noticing and appreciating where we are right now.

With writing, its always about the next thing. And while I understand that, but it’s not the way I want live my days, to measure out my life. I want to rest on my laurels. I want to breathe. I want to rest.

*

I started thinking about all this in response to the book Creative Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto, by Ayun Halliday, whose comics I used to read in Bust Magazine back in the days when I was learning to call myself a feminist. I think I am the small potato I am because of Halliday’s influence, because of her example that it’s possible to live a creative life, to combine that life with motherhood. Blogging’s DIY ethos in line with her zines and off-off-Broadway plays. Her example of how exactly one goes about confidently in the direction of one’s dreams and lives the life she imagines.

Most of us are never going to hit the big time. But is that really the reason we’re doing it?

It’s not the dreams themselves, it’s the direction.

I’m thinking of yoga, and how much of a pose is about reaching for it instead of actually getting there, and how it’s really the reaching that makes the process worthwhile.

If you didn’t have to reach, what would be the point?

*

I remember thinking about my goals when I was a little bit older, too old to be penning axioms by Thoreau into pretty notebooks, and I wasn’t actually thinking about Thoreau at all. But I was plotting out my life the way one might be plotting the trajectory of a line on a graph, and it occurred to me that if I tried to be a writer, to write, that even if I never achieved such goals as a published book (or two books, or three, or a bestseller, or a prestigious prize) that I’d end up in a very different and likely more interesting place than if I hadn’t tried at all.

That it’s actually impossible to lose this game.

*

What Thoreau actually said, from Walden: “I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.”

October 13, 2021

Class Reunion: ENG 369Y 20 Years Later

During my third year of undergraduate studies, from 2000-2001, I was part of ENG 369Y, a creative writing workshop led by Dr. Lorna Goodison through the Department of English at the University of Toronto.

For so many reasons, many illuminated below, this class would be an unforgettable experience, though it seemed especially remarkable when—two decades later—four of us from the class would all be publishing books within the same year and a bit.

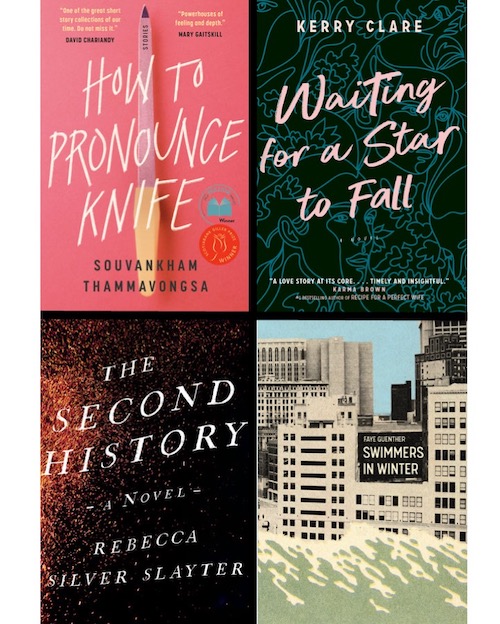

- Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife was published in April 2020, and it was awarded the Scotiabank Giller Prize that year, as well as the 2021 Trillium Book Award, among other accolades.

- Faye Guenther’s Swimmers in Winter came out in August 2020, and it has been a finalist for both the Toronto Book Award and the 2021 ReLit Award.

- My book, Waiting for a Star to Fall, arrived in October 2020, and the Montreal Gazette called it, “Subtly complex […a] romantic drama tailor-made for the #Metoo age.”

- And Rebecca Silver Slayter’s The Second History found its way into the world this summer, with no less than Lisa Moore writing that it’s “one of the most honest renderings of romantic love I’ve ever read. [A] truly mesmeric story, tender, unflinching, quakingly good.”

To me, the serendipitous occasion of our new releases after all this time seemed like an splendid opportunity for us to reconnect and reflect on our time together, as well as so much that we’ve learned about writing in all the years since then, and so the four of us shared our thoughts and ideas via email.

tell us about 20 years in the writing life, about the trajectory of your writing life since our class together in 2000.

Kerry Clare: I don’t think I had a focussed relationship to writing at all in the first ten years after our class together, even as I completed a MA in Creative Writing at the University of Toronto from 2005-2007. There is a line in Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life that I may have misremembered, but it’s about a superficial idea of writer-dom being analogous to one admiring the way one looks in a particular hat, and I always thought she was talking about me, which was mortifying.

When I finished graduate school, I worked for two years reading financial documents all day long, which was not fun, but gave me stability and a salary, though little in the way of creative inspiration. It also gave me parental leave benefits, which I used when I had my first child in 2009, and becoming a parent really seemed to up the stakes for me writing-wise. I became invested in the world in a more meaningful way, and therefore had more to write about. My first big success in writing was an essay about new motherhood I published in 2011, and this led to my first book, the essay anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which I edited and was published in 2014.

At this point, I wasn’t sure that writing fiction was going to be my destiny, and was even making peace with that (throughout this entire period, I’ve been blogging, which has been a creative lifeline), but then something clicked shortly after my second child was born and I finally figured out how plot works. My first novel, Mitzi Bytes, was published in 2017, and I’ve been writing them ever since, and though I am constantly terrified that one day I won’t know how to do it anymore, it seems to keep happening.

Souvankham Thammavongsa: I am not a very good example of a writing life because my trajectory isn’t a simple one and it is not for everyone. I don’t think anyone would want it. I worked for fifteen years in the research department of an investment advice publisher, I counted bags of cash five levels below the basement, I prepared taxes. This work helped me write what I want and it didn’t take away my desire to write. I still have that from 2000, this desire to write, but it wasn’t anything someone taught me.

Faye Guenther: I stayed at the University of Toronto to do undergraduate and graduate degrees in English. Then I went to York University and did a PhD in English. While I was a student during those years, the jobs I had to support myself weren’t related to writing, but they showed me things about the world and this is useful to a writer. I’ve found that no matter what you do, the key is to make the time to write. My writing life has also been shaped by who I’ve met along the way, including fellow writers. In 2017, I published a chapbook of poems and short fiction, Flood Lands, with Junction Books. In 2020, I published a collection of short fiction, Swimmers in Winter, with Invisible Publishing.

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

Rebecca Silver Slayter

Rebecca Silver Slayter: I decided to stop writing not long after that workshop. I think, to reverse what Souvankham said, I worried my desire to write might be something someone had taught me. That I had lost track of why I wanted to write at all.

So I stopped for a year. Or two. Or three? It felt like forever because I was 20-something and everything was forever.

And meantime I decided to make my life and work writing-adjacent. I interned at Quill & Quire and The Walrus. I worked for a startup children’s publisher. I did odd jobs to complete the financial math, yardwork and errands. Eventually I was hired for my dream job, working as managing editor for Brick literary journal.

Sometime in the midst of that, I met my husband, and told him, proudly, how I had made the tough, mature decision to give up writing, and he listened and nodded and then said, I know you are a writer, with such certainty that I didn’t know how to doubt him and I began writing again. And I found to my great joy what I had been missing in those earlier writing years; a desire to write that easily overtook the desire to be a writer.

I did graduate studies in Montreal, where I wrote the first draft of my first novel, In the Land of Birdfishes. When I graduated, I returned to Nova Scotia, and bought a house for a song in Cape Breton, which I will be renovating for the rest of my earthly days.

This is for me a very good place to write, near the ocean and the highlands, in a community where music and storytelling are woven into everyone’s daily life. Here I published my first book and then wrote and rewrote and rewrote my second book, which was just released this summer: The Second History. It took me eight years from first draft till now, mostly because I tried to write it faster than I’m able to. It turns out I’m a writer who needs to take my time…

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

what was the best thing the writer you were in our classroom had going for them? And what writing advice would you give that previous incarnation of you? (Though would you even have taken it?)

ST: My intuition. I listened to everyone, and knew when not to. This taught me how to pick through edits. When we see edits, sometimes it’s about the person and their life experience and it doesn’t mean they are right or know but you have to be generous and allow them to have their thoughts.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it. I want myself to encounter and work through those difficult and lonely moments. I don’t want anyone to hold my hand or do me any favours or make it easier or easy. I like the difficult, and I want to continue with that difficulty.

RSS: One of my clearest memories of that workshop was of Professor Goodison saying, as we discussed one of my poems, “You come from preachers, right?”

I was tongue-tied with confusion. “What?”

“Your people, they’re preachers, right?”

I had absolutely no idea what she meant. “No….” I stammered.

“Then why are you preaching at me?” she asked.

Oof. Caught. I was constantly preaching. Trying to find a much-too-simple way of understanding much-too-large things. I had a weakness for sentences that began like “Love was…”

I think somewhere in this is both my weakness and strength as a writer (probably as a human too). It is writing-in-bad-faith to just polish up pretty turns of phrase that sound truish. To go around making tidy summaries of untidy things. But… I think if I mine deeper I can find underneath that impulse what drives me to writing still, and to reading itself… The sense that there is some luminous other way of noticing the world that will make it brighter, stranger, more visible. That certain words can be incantatory, a pathway to looking again and seeing more.

I have two small children, and have found it astonishing to witness language dawn within a person who formerly had none. How each child altered a bit around the language they used. How they learned what it was then to be nervous, even tired, even thirsty. How what began as the ragged, indeterminate longing of a baby’s howl became so clear, so precise, so unmysterious. And I miss a bit the mystery. The wonder of watching a peer being who doesn’t know what yesterday is. But I think there’s another way that language can give us back what experience has made ordinary. And I think that’s what I was searching for twenty years ago and search for still, but with a few degrees more purpose. And a lot more joy.

So I would maybe advise myself something like this: First, don’t write any more poetry. You are very bad at it. And for a time, don’t write at all. Wait until the desire to write is something you have to resist. Wait until it wells up in you. And then go find the joy of writing words that make you look again, more deeply.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it.

Souvankham Thammavongsa

FG: I remember being openhearted and creative. The writing advice I would give my earlier self is to be bolder. I think when boldness is combined with a practice of being open with yourself and to the world, there is a sharpening of creative focus that can happen and a strengthening of creative perception, no matter what challenges life brings.

KC: The writer I was in our classroom had no idea how much she didn’t know, and far more confidence that she deserved to have, and I’m so happy she did because being 21 is hard enough. I was not a serious person or a serious writer AT ALL. (I remember that Souvankham appeared to be both, and it was such a powerful example for me, though I think I was still too young to fully appreciate it.)

What a tremendous opportunity to develop my skills that class should have been!! But I did not work all that hard, honestly, too busy checking out my look in the hat, remember? I mainly wrote poetry because you could finish a piece in a few minutes. This did not mean my poetry was good, however, although I think sometimes some of it was.

If I could give that writer I was any advice it would be to write something REAL, instead of something you think sounds like something that could be real. (And find writers you love, instead of reading all the writers you’re supposed to love.)

For the record: I would not have listened.

what roles have literary journals and small presses played in your writing career?

RSS: I know literary journals and small presses better as a worker than as a writer. But I am shaped permanently by my years at Brick literary journal, and by the trips I made then, twice a year, to Coach House Press, where the journal was designed at that time.

The Coach House basement was a kind of church I visited like a disciple of those beautiful machines for cutting pages and laying type … and of the people who made them run and knew the stories of an older Toronto and the mesmerizing adventures then had by not-yet-famous writers. In a way that is both corny and essentially true to me, that is what I feel a tiny part of when I write: all the people in all those tiny offices and studios and nooks making small-press books and magazines; their labours of love, their care and bravery, those parallel arts of ink and paper, alongside those of prose and plot.

They taught me what was foundational to writing; the courage and the care of the work. And the kinds of community it can build.

FG: Reading literary magazines gave me an awareness of community. They were the first space where I was published, and I know this is true for many writers. Smaller presses often foster innovative and ground-breaking work. They frequently publish voices and stories that historically have been marginalized. I think smaller presses are important for energizing and sustaining a vibrant creative culture.

My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance

Kerry Clare

KC: My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance, especially in the wake of the novel I’d written for my Masters thesis that went nowhere (because it was boring!) because I was really feeling kind of discouraged, and then this message from the universe arrived suggesting maybe I should keep going after all. In the next few years, I would publish pieces in TNQ and other journals, and the high of an submission being accepted has never diminished for me. And then Goose Lane Editions, a remarkable Canadian indie press with an impressive history, published The M Word, and did the book such justice. Without literary journals and small presses, I’d be nowhere.

ST: Literary journals teach you things a writing class or editor or a dear friend and family cannot. They don’t love you and are not beholden in any way. They teach you about rejection—what that feels like, what to do with it. They are often the first place where we get to see ourselves in print. It’s important for a writer to understand the difference between seeing yourself in print and publishing a book. They are not the same.

what are your favourite memories of our class?

ST: I remember the talent and fun. There were so many writers in that class who are more talented, more ambitious, more interesting…but they aren’t here, or with books. They became lawyers and engineers and professors. I always keep that in mind. Having a book doesn’t mean I am good.

KC: I have so many memories! I don’t know if we were particularly interesting as a group, or if it was the work of Professor Lorna Goodison in creating community, or just the particular mix of experience and personalities in our class, but I felt very connected to everyone. I think we were a well written cast of characters.

I remember Souvankham on the very first day, and how she impressed me so much with her sense of herself. I remember we had to write a poem inspired by postcards, and mine had a field of sunflowers and said, “Welcome to Michigan,” and I wrote a poem with the line, “I won’t forget the motor city.” I remember REDACTED who wrote a poem with the line, “Let’s make love in the astral plane,” and I was seriously impressed by how sophisticated he seemed. And someone else who wrote a poem about someone sucking on her toes while listening to Robbie Robertson sing “Somewhere down the crazy river.” Everyone seemed to be having a lot more sex than me. (One could not have been having less sex than me.)

I remember Faye seemed especially interesting, partly because she seemed kind of badass with a shaved head, and we always sat in opposite corners of the room. And how I was in love with the name “Rebecca Silver Slayter,” which belonged to the woman who often sat in the same corner as me and whose work I felt very drawn to.

I think it’s kind of wonderful that in addition to the four of us, plenty of others in that group have gone on to very interesting careers in academic, television writing, and more.

One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

Faye Guenther

FG: I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from our teacher Dr. Lorna Goodison. One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

RSS: This sounds like very cheap, opportunistic flattery, but honestly, though I remember well many of the talented, interesting writers in the class and their poems and stories, what I remember most clearly is the three of you.

I remember how beautifully Souvankham’s work was always laid out on the page in lovely, tiny type—the form so perfectly echoing the work itself, the grace and economy and polish of her words; how her work seemed always already complete, and I was stumped on how to write any feedback that didn’t just feel like tampering.

How Kerry’s writing was funny and powerful at the same time, and I hadn’t even known that was possible. How she seemed so at home both on the page and in the classroom, warm and open and at ease in a way that awed me. I remember Faye’s compassion for her characters, their rich interiority. How reading her stories felt like someone whispering in your ear, that intimate.

My strongest memory of the class was the first one. When we went around the room and each offered up our names.

Souvankham was near the end, seated at the table perpendicular to the one where Professor Goodison sat.

After she said her name, Professor Goodison asked, “So what do you want to be called?”

I was caught off guard by the question, but Souvankham answered clearly and immediately. Without blinking or skipping a beat, she said: “I want to be called a writer.”

Professor Goodison looked at her and Souvankham looked back. Then she said, “I’m going to call you Sou.”

And I was as astonished as if Souvankham had wafted out of her seat and up into the air between us. I was at that time so uncertain, so full of twenty-one-year-old desires to be interesting, to be brave, to be invisible and/or famous. I would have probably told Professor Goodison she could call me whatever she wanted. Or tried to guess what she might prefer me to be named.

Year by year over these last twenty, I get a little closer to what Souvankham already had then. That certainty. That clarity of purpose and identity as a writer that struck me silent when I was twenty-one.

March 12, 2018

Yoko Ono, “The Riverbed,” at the Gardiner

I loved Yoko Ono’s “The Riverbed”, which we went to see yesterday at The Gardiner Museum. An exhibit whose first part is “Stone Piece,” an arrangement of river-worn stones which we are invited to pick up, and contemplate, and (for some of them) to discover words written on their bottoms, and then replace the stones in a different arrangement, the exhibit ephemeral and ever-changing, always moving, like a river itself. Cushions around the display invite viewers to sit down and watch the scene, the way we might want to sit by the side of the river, and the effect is similar—relaxing, interesting, and insightful. It’s a scene where adults and children alike are excited to be taking part in the exhibit, to be a part of things, and watching this is interesting as well.

Next we move on to “Mend Piece”, where broken crockery has been placed on the table and we are invited to put the pieces together using tape, and string, and glue. A fascinating process for so many reasons—because the pieces we’re “mending” weren’t necessarily put together in the first place, the idea that to mend is a creative act, to make something too, how mending is restorative and generative at once. About how out of broken things there can be made something new, and strangers sitting together at the table connect as they share materials, and also as they’re served coffee from the coffee stand that is part of the exhibit. When the “mending” is done, the new object is placed on a shelf or hung on the wall, and thereby viewers now have a piece on display at the Gardiner, which is kind of incredible.

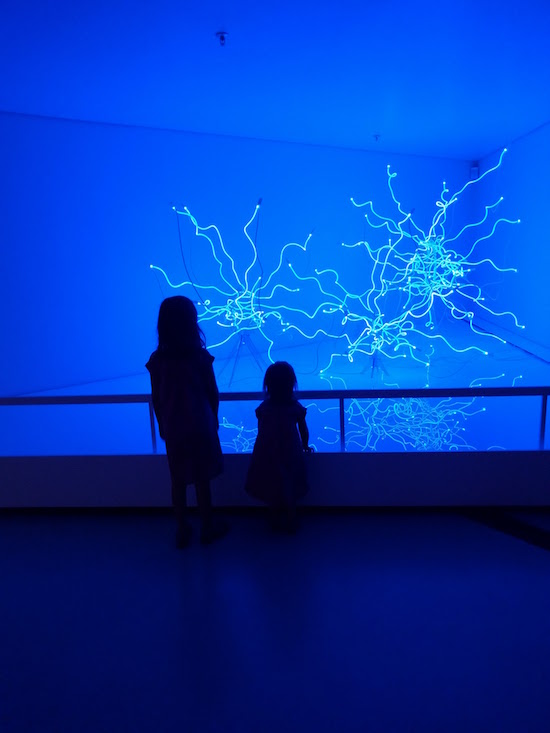

Everything is white, and there is so much light, which, when coupled with the creative acts taking place, allows for lots of thinking—but the soundtrack is the racket of nails being driven into a wall. Which was meaningful to me, being required to think over the noise, which is important. The noise too a reminder of work, the necessary parts of building anything. And the work that’s being done is in “Line Piece,” where viewers can hammer a nail into the wall and tie a string from one point on the wall to another. Which has created the most fascinating space, cushions on the floor again where you can look up and think about the web of string above, the web that would have been different if you’d never come, the web that will be something else different tomorrow. And to stand up too, pop my head up through the web and contemplate the networks of string from above… It’s about connection, and shelter, creativity and possibility.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the exhibit. Conceptual art can go all kinds of ways, and making the viewer a participant in the process doesn’t always succeed in being meaningful. But I still remember the story of John Lennon falling for Ono back in the 1960s’ when he went to her exhibit and climbed to the top of a white ladder to see a word through a magnifying glass, and the word he saw was YES. After our experience yesterday at “The Riverbed,” now I see how that could happen.

July 17, 2016

Chihuly at the ROM

The summer is flying by, as summers do. I spent last week in my hometown of Peterborough visiting my parents, which was lovely, hot and fun. And now back in the city, we went to the ROM yesterday to see the Chihuly exhibit.

I’d never heard of Dale Chihuly before the ROM magazine arrived awhile back with images of his work, although it occurs to me now that he’d been the artist behind the golden tree I’d photographed in Montreal a few weeks ago. And that perhaps encountering Chihuly’s work out in the world is most striking way to experience it, but the ROM exhibit itself was pretty stirring.

My favourite thing about the exhibit was that it’s the rare thing that all four of us—whose ages range from 3 to 37—could appreciate on the same level. The same things I loved about it and was struck by were what struck the children too, and we were all of us in awe of the colours, the light. The spectacle.

And like nearly everybody else, my favourite part of it was the Persian Ceiling, under which we laid down and just looked, and there was so much to see, and how the light from the ceiling transformed the world all around us.

September 11, 2014

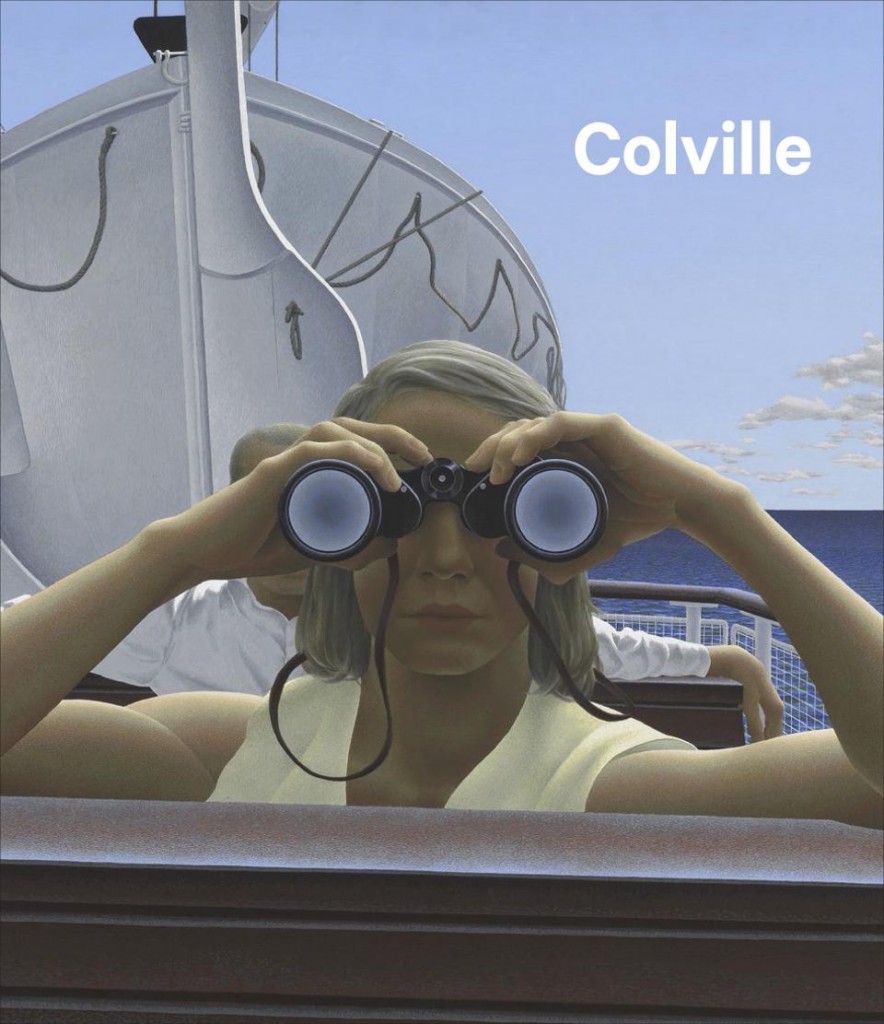

Colville

I don’t know if there is a better exhibit than Alex Colville (now on at the Art Gallery of Ontario) to take your five year old and one year old to, because the latter will be gripped by all the images of dogs, while the former sees her own world reflected in the paintings, but rendered just unfamiliarly enough to warrant another look. We note people and animals suspending in space, captured in motion—horses, dogs, a little girl with her skipping rope. “What do you think’s going to happen next?” Which is the very point. Plus the defiance of gravity. And the strange ugly beauty, hydro corridors, overpasses and smokestacks. The sky’s enormity. We found it fascinating to learn that Colville’s art was so informed by his commute to work, that same stretch of road, a seemingly dull track. And also the sea pictures, all that blue.

Andrew Hunter’s new book, Colville, designed to accompany the exhibit, gives a marvellous sense of the artist and his power, and just as the exhibit does, of his context as well. In his essay in the book, Hunter posits Colville as a place, and finds connections to that place not just in geography, but also in literature, music, film and popular culture. As befitting a man whose own life was so often his subject, the book embraces Colville’s biography as well, and more than 100 reproductions of his work. It’s a really wonderful complement to an extraordinary show.

August 25, 2013

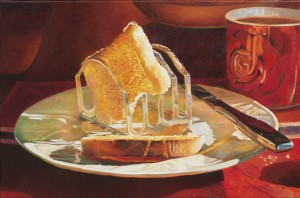

Mary Pratt: On Blogging, and Preserving Light and Time

It is not a huge leap to look at Mary Pratt’s paintings and have thoughts turn to ideas about the containment and preservation of time. Not least of all because of her paintings of preserves, jams and jellies. Or because she shows that jam jars are containers of not only condiments, but also of light. In the essay “A Woman’s Life” by Sarah Milroy, part of the Mary Pratt book, Pratt recalls early inspiration in her mother’s jars of jelly: “Oh they were gorgeous… she would arrange them along the window-ledge–they were west-facing windows with the light coming through–red currant jelly, highbush cranberry jelly, raspberry jelly, blackberry jelly–all as clear as glass.”

In her work, Pratt also includes more prosaic containers, such as tupperware, and ketchup bottles, as well as preservation agents that capture light with a different kind of beauty–tin foil, saran wrap. Underlining this idea of preservation is that Pratt’s paintings themselves have been painted from photographs, that with a camera Pratt has been able to stop time and preserve a moment in the whirl of domesticity–a supper table that will soon be cleared away, for example. In Sarah Fillmore’s essay “Vanitas”, Pratt notes that “The camera was my instrument of liberation. Now that I no longer had to paint on the run, I would pay each gut reaction its proper homage. I could paint anything that appealed to me… I could use the slide to establish the drawing and concentrate on the light, and the content and the symbolism.”

Whilst reading the Mary Pratt book, which has been created to complement the exhibition of Pratt’s work that will be moving across the country in the coming months, I kept drawing parallels between her work and the womanly art of blogging. This precludes any arguments about amateurism of course, however much some may insist that “blogger” and “amateur” are in fact synonyms. Because Pratt is no amateur, and neither are the bloggers who make art of the form, who craft their posts themselves in order to “pay each gut reaction its proper homage.”

“…it comes from a longing to hold truth in your hands, to feel something of your own existence–a longing to feel alive… The painting of the jelly jar is really about the way that light shines through the glass, the way that light is preserved, like jelly, for all time.” -Sarah Fillmore, “Vanitas”

Pratt captures the domestic, the seemingly mundane. And yet behind her rich but also simple and familiar images lie deeper stories. Her painting “Kitchen Table”, the first she created from a photograph in 1969, is at first a quiet scene, a table at once empty and yet crowded with the remains of a meal–a ketchup bottle with its cap off, a hotdog left uneaten, crumbs on a plate, drinking glasses in varying states of emptiness (or fullness, perhaps?). And yet, as Catherine M. Mastin points out in her essay “Base, Place, Location and the Early Paintings”, “Pratt’s postwar-era family table is a site of constant labour, meal after meal–which all fell to Mary, with no foreseeable end.” On a more personal note, Pratt’s “Eggs in an Egg Crate” was the first work she completed after the deaths of her infant twins, a painting whose symbolism wasn’t clear to her until somebody else had pointed it out–that the eggs in the carton were empty.

For all their luminosity and the domestic focus, Pratt’s paintings are also wonderfully subversive. Her eggs are usually broken, is what I mean, the cake half-eaten and cut with a big sharp knife, the bananas in the fruit bowl are just a little too ripe. The meat in her “Roast Beef” is a charred hunk (and Pratt recounts in Milroy’s essay, “I can remember when I first showed it in a gallery [and] I heard a woman say, ‘Well, I guess she can paint, but do you think she can cook?'”). Milroy is correct that “In this day of highly stylized food photography…, Mary Pratt’s work seems ahead of the curve,” and yet Pratt’s food paintings are always just a little “off”–the leftovers from a supper of hotdogs, for example, or the casserole dish in the microwave. This is food that people eat, instead of a lacquered sandwich intended for a magazine cover. Hers is a messy, imperfect domestic scene, and yet there is beauty in these scenes that are captured precisely as they are.

Her images of meat and animal carcasses suggest something basic and bodily about domestic life, a suggestion echoed vaguely in the images of her model “Donna”. “That’s what women do,” Pratt recounts in Milroy’s essay. “They wrap things up, or unwrap them, or cut them open, or chop them, ready for the oven.” Fish are also a recurring image in her work, not surprising considering she’s based in Atlantic Canada, but here is the rarely seen flip-side of maritime life–“Salmon on Saran”, “Trout in a Ziploc Bag” or “Fish Head in Steel Sink”. They don’t write shanties about this kind of sea. And then there is the fire, Pratt’s burning dishcloth on her “Dishcloth on Line” paintings. That same agent used to wipe down the table of dinner-after-dinner is annihilated into a glorious flame which captures the light as intriguingly (and eternally, now that Pratt has preserved the image) as do the far more innocuous jars of jam on the window sill.

Whoever thought the kitchen was a scene of mundanity probably wasn’t looking…

In her essay “Look Here”, Mireille Eagan writes that “Ultimately, [Pratt] asks the viewer to see; she tells us: “Look, here.” Which is what the very best bloggers do too, instead of “Look at me!” using their blogs to implore their readers to, “Look at this!” The result of this being the “sideways autobiography” that Eagan refers to of Pratt’s work. There is no over-arching narrative here, and instead we come to understand the depth of these writers’ lives from the objects, moments and stories they choose to include in their blogs, each individual post its own still-life. Like Pratt, these bloggers are curating their lives, crafting something permanent out of the whirl of the ephemeral. As Eagan writes of Pratt: “Her images reveal a pattern of privacies, of things half-visible, half-said–but articulated, nonetheless. They represent a lifetime of looking closely, an intimation of the buzzing pause before one turns and continues.”

Mary Pratt is available from Goose Lane Editions. Read more about this stunning book here.

October 25, 2010

El Anatsui and Margaret Drabble, via Heather Mallick

When I Last Wrote to You About Africa, the retrospective of Ghanian sculptor El Anatsui now on at the Royal Ontario Museum, was one of the most exciting, beautiful and powerful exhibitions I’ve ever seen. So you can imagine my delight upon reading Heather Mallick’s column last weekend, as she draws a parallel between the show and Margaret Drabble’s ideas as expressed in her latest book The Pattern in the Carpet. Marvelous worlds colliding!

Mallick writes of the exhibit:

I visited this weekend for the second time, for the pleasure of being shocked by beautiful acreage. The possible meanings leap out at me, what El Anatsui is saying about the way we live now.

I like to tell fellow ROM visitors (strange how they back away from me) about my theory, borrowed from the novelist Margaret Drabble, about why people are so angry and unhappy now. Suffering from the illness known as “affluenza”, they are told to view life as an economic ladder, a vertical clamber to success. But people are falling off the ladder now, or are stalled mid-rung, and it hurts.

Drabble says life is not a ladder but a jigsaw. It moves sideways and around, no one event knocking you into the abyss. Suddenly a job loss or a sick child or a bad divorce is just another piece in the broad jigsaw, part of a pattern in the carpet. No section of the jigsaw is more important than any other. This is a comfort when the wheels come off.

That’s what El Anatsui’s metal curtains say. The bigger ones do look like Canada, well-assembled and prosperous, with random wrinkles representing our national miseries.

March 4, 2010

franny and zooey by colleen heslin

franny and zooey by colleen heslin, as seen in issue 32.3 of Room Magazine. Image used here with permission of the artist. Because I love it.

franny and zooey by colleen heslin, as seen in issue 32.3 of Room Magazine. Image used here with permission of the artist. Because I love it.